CHAPTER 2

HEART OF IRAN

THE GEOGRAPHIC HEART OF IRAN COMPRISES AN INCREDIBLY DIVERSE AND IMPRESSIVE GROUP OF HISTORIC TOWNS AND MONUMENTS, RANGING FROM THE SHIA HOLY CITY OF QOM TO THE ANCIENT RUINS AT PERSEPOLIS TO THE CLASSIC CITY OF SHIRAZ. IT IS ALSO WHERE THE SMALL MOUNTAIN TOWN OF NATANZ IS LOCATED, WHICH IN RECENT YEARS HAS BECOME A BIG DOT, AND PERHAPS EVEN A TARGET, ON THE WORLD GEOPOLITICAL MAP BECAUSE OF A MAJOR NUCLEAR SITE BEING DEVELOPED NEARBY.

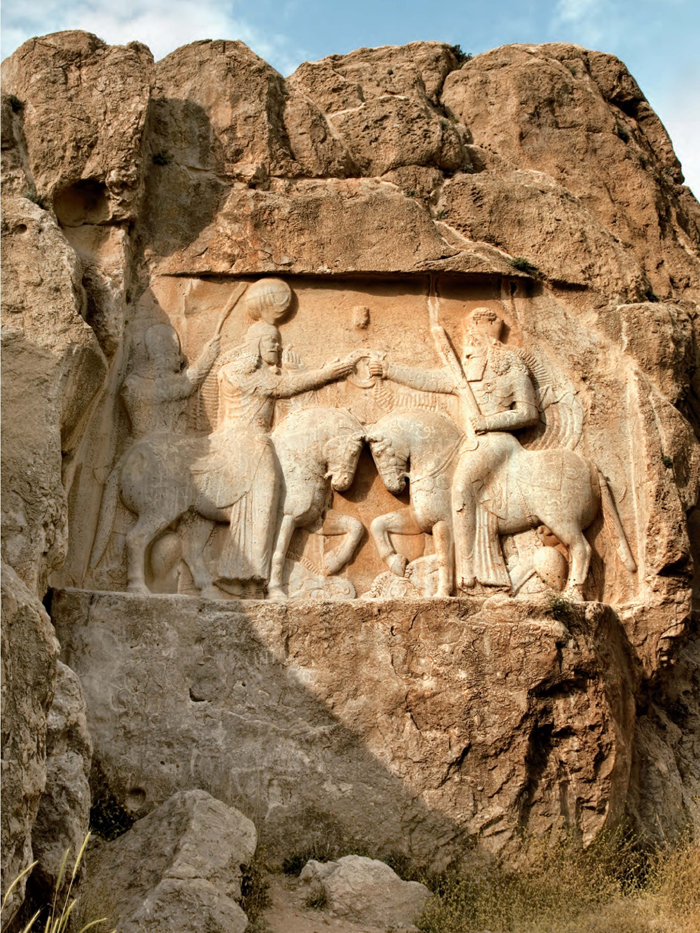

A third-century Sassanid relief at Naqsh-e Rajab depicting the Zoroastrian high priest Kartir with an inscription of his words of devotion to the Sassanian kings.

Along the major roads that connect these sites in central Iran, one can see caravanserais, ancient roadside inns that supported travelers on trade routes, including those on the legendary Silk Road. While most of these inns are returning to the earth from which they were made, some have been resurrected and turned into impressive boutique hotels.

The first major city south of Tehran is Qom, which contains the second most important religious site in Iran—the Hazrat-i Masumeh, honoring Fatima, the sister of the eighth imam, Imam Reza (ad 765–818). It was in Qom that Ayatollah Khomeini studied and developed his thoughts on religion.

The drive southeast from Qom goes though major towns such as Kashan, Yazd, and Kerman, each with a unique set of shrines and bazaars. This particularly dry area of the country has long struggled with maintaining a water supply, and the people there have developed an impressive irrigation system and maintain a potable water supply. For 2,000 years, they have drawn water from the mountains to the cities using subterranean channels called qanats. Outside of the cities, the qanats can be identified by their similarity to large molehills.

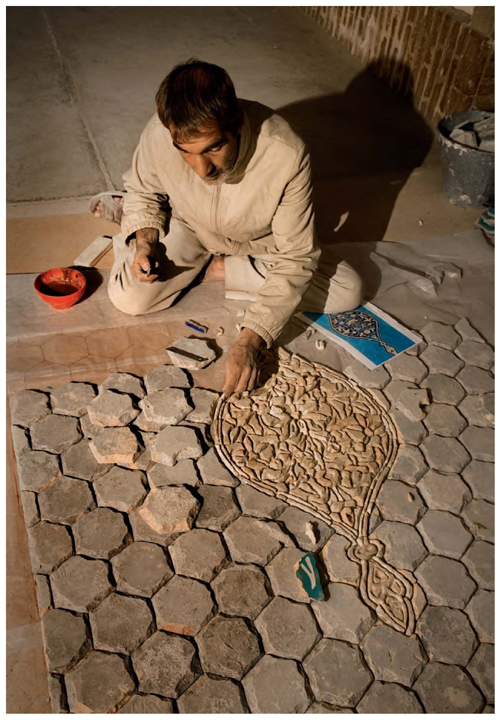

The area’s citizenry have also been ingenious in their efforts at interior climate control. In Yazd, in particular, there are many examples of wind towers known as badgirs, which can be described as ecological airconditioning. Warm air is drawn in and down from the top of a tower on one side of the home and then passes by running water under the house in a qanat, whereby the air is cooled. The cool air is then led through the house through holes in the walls of the living quarters, which are often elaborately decorated with beautiful tile work. Across from the holes, outlets lead the air back up and out through the other side of the badgir, effectively circulating the air.

In the southern part of central Iran lies Bam, with its adobe complex dating back more than 2,000 years. This UNESCO World Heritage Site suffered major damage in December 2003 from a 6.6 magnitude earthquake, and tens of thousands were killed in the area. The smaller but similarly built adobe Rayan Citadel, 75 miles to the northwest, was spared the brunt of the devastating temblor.

Shiraz, 570 miles south of Tehran, is known as the city of poetry, and here lie the tombs of two of its great poets, Hafez and Saadi. Shiraz is the namesake for the famous grape, which was uprooted for a time after the 1979 Islamic revolution but can still be appreciated as a native fruit. The city is also a major center for the less glamorous but important production of sugar, fertilizer, cement, electronics, textiles, and rugs, and a major oil refinery is also located there.

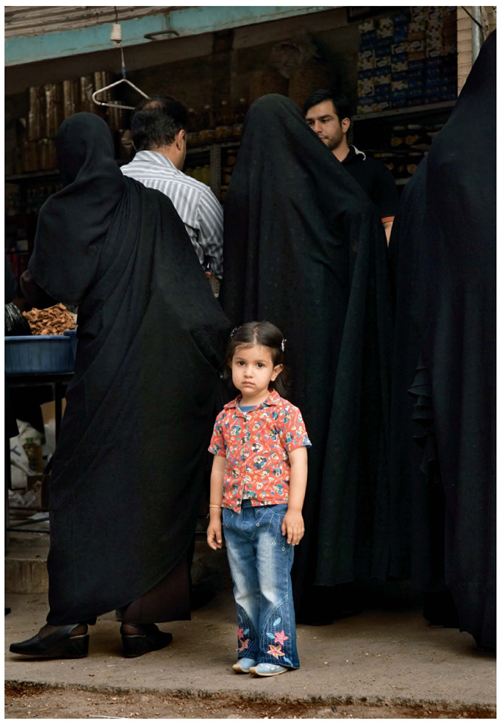

Ninety-seven miles southwest of Tehran is the city of Qom, site of the tomb of Fatima Masumeh, sister of Imam Reza. It is now a city of more than 1 million, with around 60,000 attending its many religious schools dedicated to Islamic teaching. It was here that Ayatollah Khomeini denounced the shah and returned from exile in France to establish his Islamic revolutionary government. Despite the archconservative bent one might expect and observe here—unlike other parts of Iran, nearly all women in Qom wear chadors—there is a notable history of debate among the clerics and sometimes outright challenges to the state of the country’s politics.

Students on a field trip to Tappeh Sialk, an archeological site near Kashan that contains a ziggurat from the fifth millennium bce.

A group of women dressed in chadors on their way to the Bagh-i Fin, a massive garden complex created by the Safavid shahs.

The domed ceiling in Kashan’s Ameris House, one of a number of traditional houses open to the public. The property was owned by a nineteenth-century merchant.

Male and female knockers on a door in Abyaneh produce different sounds and thus alert the occupants as to whether a man or a woman is at the door.

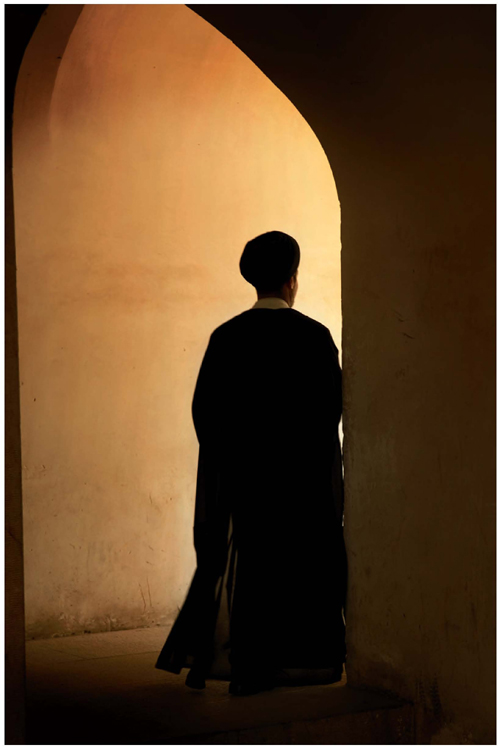

A man in a doorway in the ancient hillside village of Abyaneh, which dates back to the Achaemenian period, from 559 to 330 bce.

An Iranian tourist in the ancient hillside town of Abyaneh protects herself from the sun with a colorful hat.

Graffiti on a wall in the small town of Ahmad Abad.

One of two Towers of Silence above the city of Yazd. Ancient Zoroastrian tradition considers a dead body unclean. A code known as the Vendidad has rules for safe disposal of the dead. Bodies were placed at the top of these Towers of Silence so that natural elements—the sun and birds of prey—would aid in decomposition.

Rooftops with adobe wind towers and chimneys are part of Yazd’s unique architecture, created specifically for the harsh desert environment of central Iran.

A henna mill in Yazd. Henna is a flowering plant that produces a red-orange molecule known as lawsone. Because it bonds well with proteins, it is often used to dye skin, hair, and various fabrics, especially silk and wool. Henna has been used for body art since the Bronze Age.

A shop in Yazd.

Billboards in Yazd displaying (from left to right) an ad for a new soft drink; an advertising agency’s wishes for a happy new year (in Iran, March 20th); and a bank contest promotion offering prizes including a new car, an expenses-paid wedding or haj trip, and other prizes for making deposits in time for the new year.

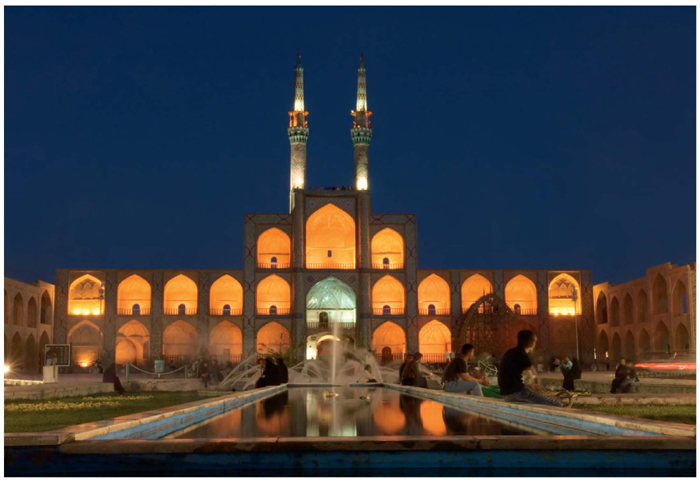

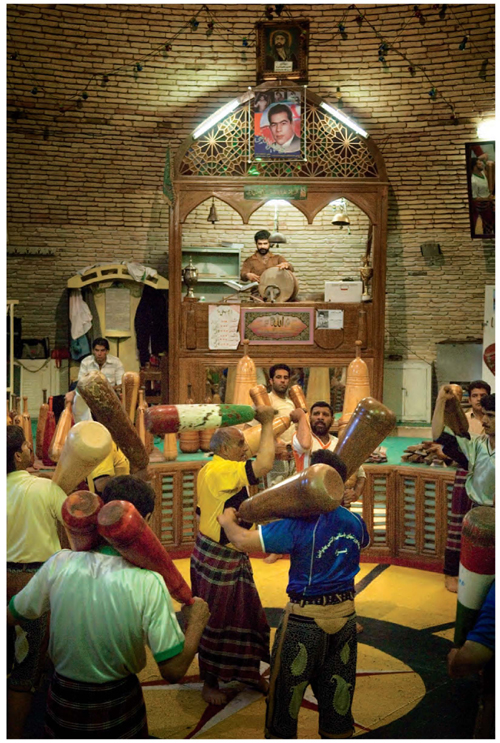

In a zurkhaneh (house of strength) in Yazd, an ancient Persian martial art called varzesh-e pahlavani (sport of the heroes) is practiced in a circular gym. An energetic beat is provided by a drummer who also recites Sufi poems and praises of Ali. Two of the most important exercises are twirling like a dervish with the arms stretched to the sides and doing calisthenics with a pair of wooden clubs called mil.

One of the greatest Sufi poets and mystics was Jalal ad-Din Muhammad Rumi (1207–1273). The Sufi Mevlevi order, the first practitioners of the whirling dervish dance, was founded in his honor after his death. Rumi’s six-volume Masnavi-ye Manavi is of such importance to Sufis that it is often regarded as a work second only to the Koran and is often referred to as Qur’an-e Parsi (the Persian Koran).

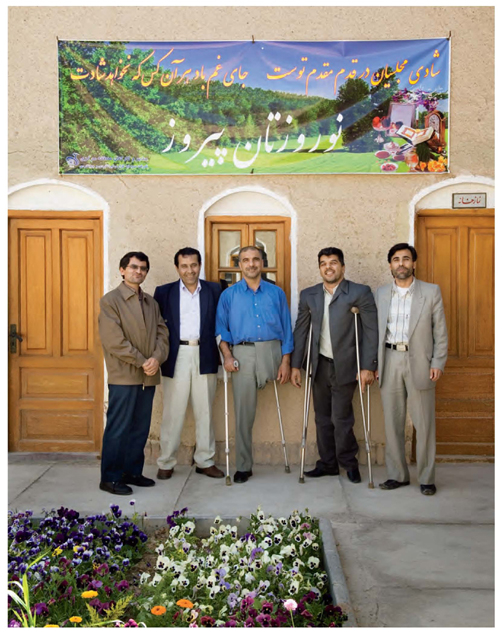

A shrine in Anar, a town on the main road between Yazd and Kerman, pays tribute to the estimated 300,000

Spices for sale at the Bazar Bozorg.

Men’s suits for sale at the Bazar Bozorg. While suit jackets and pants are popular, ties are not considered appropriate Islamic dress in Iran.

Hijabs (head scarves) on display at the Bazar Bozorg. Covering the head is mandatory for all women in Iran. Many women wear chadors, while some, especially the younger and better off, choose to go with a manteau and a head scarf. A common term for the working class is “chador class.”

A view of Shahzadeh Garden from its teahouse.

A gift store near the Shah Nur-eddin Nematollah Vali shrine in Mahan displays sports equipment and a rug adorned with a portrait of Ali.

Visitors dressed in magnae (a fitted hood) and manteau at the Shah Nur-eddin Nematollah Vali shrine.

A turquoise-tile minaret at the tomb of Shah Nur-eddin Nematollah Vali in Mahan, southeast of Kerman.

A refurbished roadside inn called a caravanserai in central Iran. These ancient “motels” were vital to the success of trade along the Silk Road.

The Rayan Citadel is about one-quarter the size of but similar in construction to the citadel at Bam, which was severely damaged by a 6.6 earthquake on December 26, 2003.

Two miles from Na’in is Mohammediyeh, a textile manufacturing town where winding streets and ancient houses have changed little in hundreds of years.

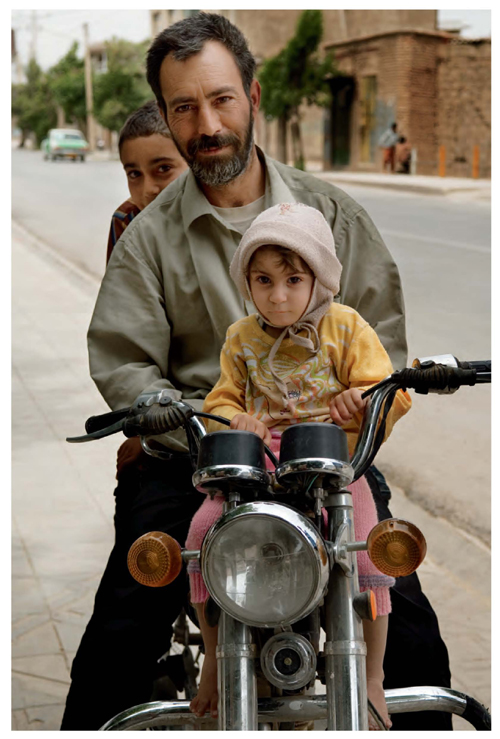

Friends hanging out in the park in Neyriz. Closeness between men in Iran has a different connotation than it does in the West.

Gentlemen on a bench in Sirjan.

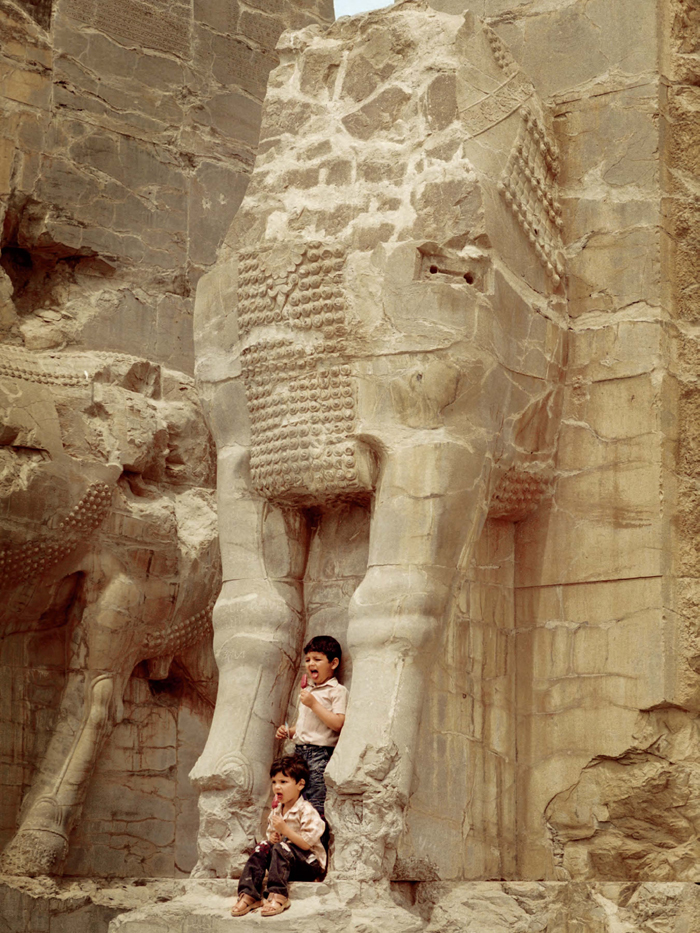

Children take an ice-cream break at the feet of a Lamassu at the Gate of All Nations, Persepolis. The city of Persepolis, known in ancient Persia as Parsa and in present-day Iran as Takht-e Jamshid (Throne of Jamshid), was a capital of the Achaemenid Empire. Persepolis is the name of the city rendered in Greek: Perses (Persian) and polis (city).

Alexander the Great took over the city in 333 bce when he invaded Persia. A few months into the occupation, a fire broke out in the city and soon destroyed it. The true cause of the fire is not known, but the two most likely scenarios are that Alexander’s troops started it by accident, or set the fire in revenge for the Persians having burned the Acropolis in Athens.

A griffin (homa) with the Gate of All Nations in the background at Persepolis. The earliest ruins in Persepolis date from around 518 bce.

Front views of the palace built by Darius the Great were embossed with pictures of the Immortals, the king’s elite guards. When I was in Persepolis, several Iranians asked me if I had seen the movie 300. Several of them had watched black-market DVDs of the movie and were not happy with the way their ancestors—Xerxes (the son of Darius the Great) in particular—were portrayed.

Iranian sightseers in Persepolis.

A relief at Nash-e Rustam depicts Ardashir I, the founder of the Sassanid Empire, being handed the ring of kingship by Ahura Mazda, the deity of the Zoroastrian religion.

Iranian tourists pose in front of a relief of two victories by Bahram II below the tomb of Darius the Great at Naqsh-i Rustam.

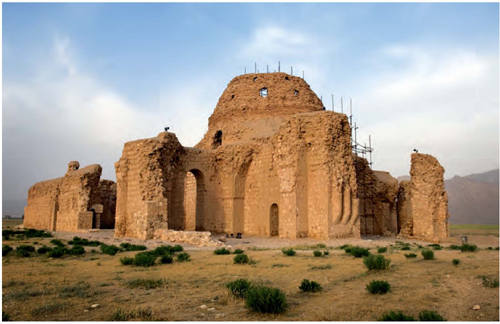

The Sassanid Palace in Sarvestan. The state religion of the Sassanians was Zoroastrianism. The Sassanid Empire lasted from ad 226 to 651.

An interior view of the Sassanid Palace dome in Sarvestan.

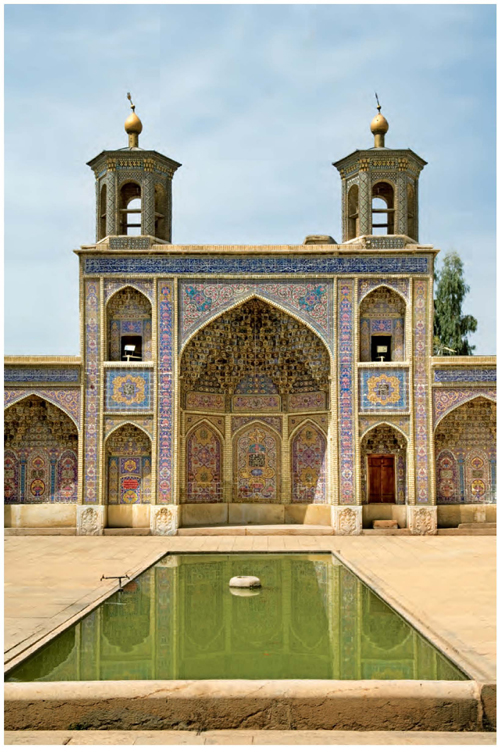

Stained glass in the Nasir al-Mulk Mosque in Shiraz. Construction of the mosque began in 1876 and finished in 1888.

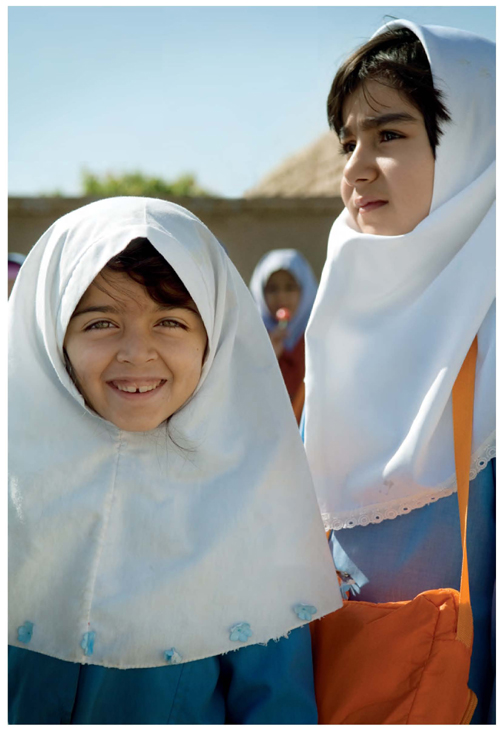

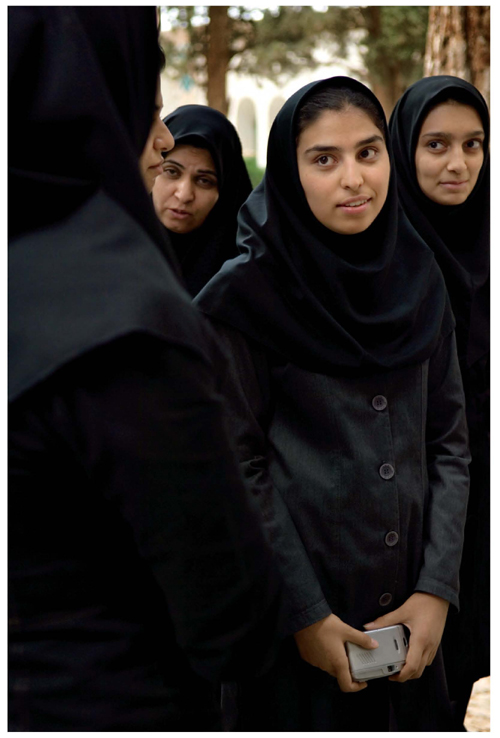

Schoolgirls prepare to enter the Jameh-ye Atigh Mosque in Shiraz, which was first built in the ninth century and rebuilt and expanded in the midfourteenth century.

A customer at a pharmacy in Shiraz sports a CIA T-shirt. In June 2007, young men who were wearing T-shirts deemed too tight or sporting hairstyles that seemed too Western were paraded bleeding through the streets of Tehran and forced by uniformed police officers to suck on plastic containers used by Iranians to wash their bottoms. The photographs were distributed by the official news agency Fars, who called the young men riffraff. The move was part of a larger “spring cleaning” against clothing considered unIslamic that Iranian police said resulted in the detention of 150,000 people.

The tomb of Saadi in Shiraz was built in 1952 to replace an earlier one of simple construction. The thirteenth-century poet traveled extensively throughout the Middle East and during one trip was said to have been taken prisoner by a group of Crusaders. Saadi’s most famous works are Bustan (The Orchard) and Golestan (The Rose Garden).

One of the nicest teahouses (chaikhaneh) in Shiraz can be found at the tomb of Hafez. The fourteenthcentury poet is considered the undisputed master of the ghazal, a lyrical poem with a single rhyme.

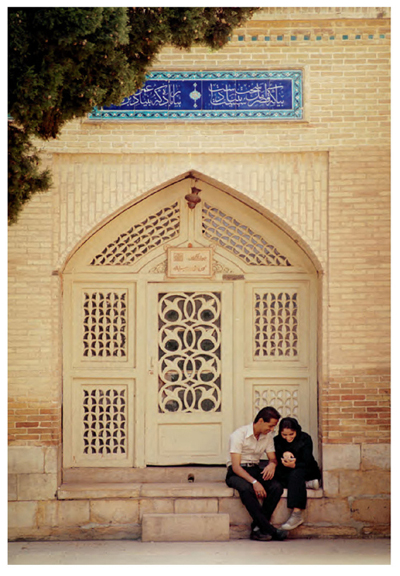

A young couple studies Saadi’s writings at his tomb in Shiraz. Poems and phrases by Saadi and the other great Iranian lyrical poet Hafez are still used in daily conversation by Farsispeaking people around the globe.

The small mountain town of Natanz is now well known as the site of one of several once-secret nuclear facilities in Iran, revealed by a dissident group in 2002, which were built by the Iranian government without notifying the International Atomic Energy Agency, a protocol it should have followed as a signatory to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. Iran has always maintained that its nuclear program is meant for civilian purposes only, and the Iranian government claimed that the United States would have blocked even a nonmilitary nuclear program. The Iranian government also believes that having such a program is an “inalienable right.” The United States contends that Iranian nuclear activities include a secret nuclear weapons program. Iran suspended enrichment activities in 2003 following international negotiations but resumed them in 2005 with the inauguration of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. A National Intelligence Estimate (NIE), which coordinates the assessments of United States intelligence organizations on specific topics, was released to the public in December of 2007. The report stated that Iran stopped the weapons side of its nuclear program in 2003. Many top American officials question the report’s findings.