PRELUDE

I slide a fishing rod into my kayak as birds begin gathering over our bay. They know what’s coming. So do I. On many summer afternoons, packs of surfacing Bluefish chase up small fish, drawing excited flocks of diving terns. The terns carry those little fish a few miles to hungry youngsters waiting eagerly on small, unpeopled islands. As it has been for millennia, so it is this very moment.

Having long studied—and sautéed—this aspect of our neighborhood both formally and at leisure, applying both statistical models and garlic as appropriate, I can report that this relationship—prey fish, terns, Bluefish, and me—shows scant sign of failing anytime soon.

The future is by no means doomed. I’m continually struck by how much beauty and vitality the world still holds.

But beauty and vitality isn’t the whole story either. In the panic among the fishes and in the frenzying terns, it’s also evident that nature has neither sentiment nor mercy. What it does have is life, truth, and logic. And it strives for what it cannot have: an end to danger, an assurance of longevity, a moment’s peace, and a comfortable death. It’s like us all, because we are natural. What anyone needs to know about mercy, one can learn by watching nature strive, seeing people struggle, and realizing what a compassionate mind could add to the picture. So I’m also struck that we who have named ourselves “wise humans”—Homo sapiens—haven’t quite realized that nature, civilization, peace, and human dignity are all facets of the same gemstone, and that abrasion of one tarnishes the whole.

My neighbor’s cottage is right on the bay, and where I launch my kayak I find him wading waist-deep with a spade, digging sea-worms for bait. Bob hopes to slide a few porgies into his frying pan by sundown. I ask how the worm digging’s going. Squinting against shards of summer light jabbing upward from the water, he says, “S-l-o-w. Even the worms are getting scarcer.” He’d earlier commented on the dearth of clams. Just a few years ago we could wade out right here and, using merely our feet to detect buried clams, emerge in an hour lugging four dozen. The hour now yields perhaps half a dozen. Nothing too mysterious; a few too many people from elsewhere, having raked over their spots, found our spot. The whole world has a pretty similar story to tell.

But I don’t pretend to speak for the sea-worms or the clams. The voiceless among us got on for hundreds of millions of years without hearing from me.

It’s true that a lot was gone by the time I got here, and that worms are waning and clams are counting down. But, there’s quite a lot left. Maybe not a lot of clams (though I’ve found a couple of decent pockets in the harbor, and my neighbor Dennis generously clued me to a heavy set over in—well, I probably shouldn’t say), but I mean in general, a lot remains. And some of what had gone has returned. You’ll see. As watching those terns and fish and the activities of my human neighbors continually reminds me, the world still brims with the living.

Yet here’s the paradox: In the cycle of seasons and the waves of migrating fishes and birds that come and go along my home coast, I still find sanity, solace, and delight, more than a few fresh meals, and the power and resilience of living things; the wider lens of distant horizons, however, reveals people and nature up against trends serious enough to rattle civilization in this century.

This is a chronicle of a year spent partly along local shores, partly exploring the world from polar regions of the Arctic, across the tropics, down into the Antarctic, and home again. In some ways, this could be any year; in some ways, it couldn’t be any other.

The world still sings. Yet the warnings are wise. We have lost much, and we’re risking much more. Some risks, we see coming. But there are also certainties hurtling our way that we fail to notice. The dinosaurs failed to anticipate the meteoroid that extinguished them. But dinosaurs didn’t create their own calamity. Many others don’t deserve the calamities we’re creating.

We’re borrowing heavily from people not yet born. Meanwhile, the framework with which we run our lives and our world—our philosophy, ethics, religion, and economics—can’t seem to detect the risks we’re running. How could they? They’re ancient and medieval institutions, out of sync with what we’ve learned in the last century about how the world really works.

So, how to proceed? I’ve come to see that the geometry of human progress is an expanding circle of compassion. And that nature and human dignity require each other. And I believe that—if the word “sacred” means anything at all—the world exists as the one truly sacred place. Simple things, right?

As we walk the shores and launch our travels, several axes of possibility—evidence, ignorance, indifference, and compassion—will form the north, south, east, and west upon which we’ll plot our course.

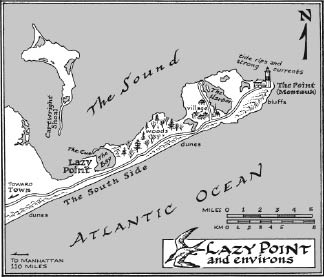

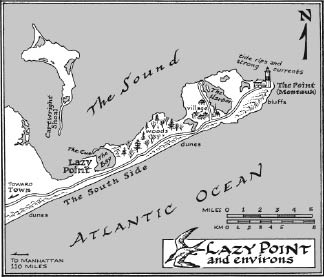

Amagansett, Long Island

June 2010