11

Building a Positive Foundation When the Baby Begins to Crawl

He wanted to know if we could sell his brother. When I hugged him tight and asked him why he wanted us to sell his brother, he said he was tired of him ruining his colouring. Two days later, he said, ‘I want to be dead since I can’t colour anyway.’

– Cheryl

Often, older siblings reach an accommodation to the new baby, only to experience a fresh resurgence of jealousy as the baby begins crawling and then walking. That’s not surprising, since now he can get into everything, including his older siblings’ art projects. Babies also start asserting their own needs more forcibly as they reach their first birthday, so it’s harder to distract them. They want what big brother has, and they’ll howl to get it. You can’t reason with them, and they get aggressive. They also master new milestones almost daily and become impossibly cute. How’s an older sib supposed to compete with that? We can forgive the older sibling for wanting to sell his brother, especially when the baby is between eight and eighteen months.

Luckily, older siblings can adapt well and even enjoy the baby’s achievements, if we give them a little support. Leaving them to manage on their own makes it more likely that they’ll resort to aggression, or become hopeless and resentful. They need parental coaching to learn to articulate their needs, protect their belongings, and find constructive ways to express their feelings, including their jealousy and irritation. If the baby is allowed to ruin their colouring and knock down their towers, you can’t expect a positive sibling relationship.

This chapter will show you how to support each of your children through those often tricky months once your baby starts to crawl, while she’s still not really verbal yet.

Ten Tips to Maintain a Peaceful Home as Baby Moves Towards Toddlerhood

I used to insist that my six-year-old play with the one-year-old, and he yelled a lot at his little brother. Once I realized that really isn’t his job, things got a lot better. Of course, the little guy still wants to get into everything his big brother is doing, so it’s more work for me to distract him, but now they have a much better relationship.

– Michelle

Like other humans who live together, even the most loving siblings have bad days and conflicts. But you can prevent many sibling tensions by following a few basic strategies.

1. Be sure your older child can protect his things from the baby. If his towers are constantly getting knocked down, naturally he’ll get frustrated. Give him a table to work on that the baby can’t reach. Make sure he knows he has backup (play the ‘Mummy, I Need You!’ game, explained here), and respond quickly when he needs your help to defend himself from the baby’s forays into his space.

2. Don’t require your older child to play with the little one. He must be respectful and kind, but he’s not a babysitter, and it isn’t his job to always include his sibling. Making older kids always responsible for younger ones often fuels resentment.

3. Describe with enthusiasm anything either child does that has a positive effect on the other child. Children are like little Geiger counters for our energy. If they get stronger energy from you for shoving the baby than for stroking her gently, they’re likely to go where the passion is. Instead, actively encourage positive interactions. You can always find something positive, even on a day when everything seems to go wrong:

• ‘You noticed the baby was fussy and figured out what she needed. Wow!’

• ‘Your sister sure smiles when you sing to her.’

• ‘You’re letting him see your car … Look, he’s so happy! … I know that car is very special to you … Let me know if you need help when you want it back.’

4. As the baby gains new skills, give your older child some of the credit. After all, research shows that older siblings are often the most effective role models and teachers for young children, who naturally want to emulate their capable big sib.1 ‘Look, he’s learning to use his spoon, from watching you.’ It’s hard for your older child to watch you exclaim over the baby’s accomplishments, but it’s easier when she sees herself as his teacher. And she’s more likely to take an active interest in interacting with him, too.

5. Rethink the whole idea of sharing. To foster generosity, help kids learn to take self-regulated turns using the ideas on sharing in Chapter 6.

6. Don’t force togetherness. If your child really resists bathing with his sibling, try to work out separate baths, at least most of the time. If the little one always disrupts story time, put him to bed first so the older one gets a calm story at bedtime.

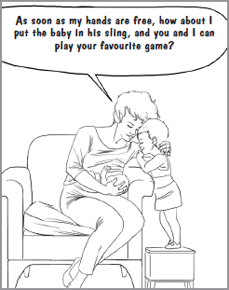

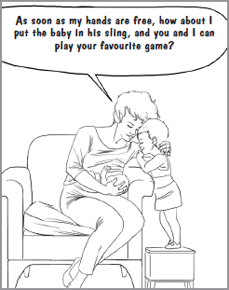

7. Notice those troublesome times of the day and structure them differently. When your older child comes home from pre-school out of sorts, put your baby in a sling and shift everyone’s emotions with a short ‘family dance party’ that gets everyone laughing and singing. At that bewitching hour while you’re trying to get dinner on the table, let your older child help you in the kitchen while the little one plays on the floor or watches from a backpack.

8. Monitor the signals that indicate trouble brewing. If you notice your child getting testy, step in to help her before she lashes out. Sometimes kids need help navigating an immediate challenge with a sibling. Other times, they just feel stubborn and are taking it out on their sib. In that case, some connection with you – particularly laughter – defuses the tension, but promise yourself to start using preventive maintenance (as described in Chapter 2) to help her with her feelings, beginning today.

9. Don’t take sides. Scolding your child to be nicer to his little sibling doesn’t work. In fact, when parents are seen as favouring the younger child, the older one actually gets more antagonistic and aggressive to the younger one.2 So treat both children as equally involved in creating the problem, even if one is just a baby.

Instead of: ‘Stop being mean to your brother!’

Describe what you’re observing, without any blame: ‘I hear loud voices … It sounds like you two are having a hard time … You both want the lorry … Now David has it and Malik is crying … What can we do to solve this problem?’

10. Instead of punishing, help kids with emotions and empower them to repair after fights. As parents, we’re understandably desperate to stop sibling conflicts. So we fly into high gear to figure out who’s at fault, quickly blaming one child as the perpetrator. Unfortunately, this reinforces the roles of both victim and aggressor. Families who punish children for fighting often incite a cycle of revenge. By contrast, in families where children aren’t blamed, but are empowered to ‘repair’ their relationships with each other after a fight, the kids end up closer.

Dividing Your Time

Your mother is always calling you by someone else’s name, or saying ‘not now’ and ‘in a minute’ and ‘can’t you see I’m [doing something with some child that isn’t you].’ … But those scarce resources, the ones that leave me feeling guilty and inadequate, mean they must learn resilience. They must find a way to share, to wait, to do without, to take their turn – and to ask for what they want and need, even when no one else notices that they have a problem.

– KJ Dell’Antonia, ‘Motherlode,’ New York Times

This won’t be news to you, but the hardest part about having more than one child is that your baby needs you 24/7, while the children you already have still need you almost that often. How can you divide your time when more than one child needs you urgently?

1. Don’t divide your time evenly. Instead, meet their unique needs. Naturally, your baby needs you almost constantly, while your three-year-old can manage some things himself and can even play for short periods of time without your intervention. Your five-year-old needs more of your time than your eight-year-old, who needs more of your time than your eleven-year-old. So your kids don’t all need the same amount of time from you. What they need is to know that they can count on you when they do need you.

2. Let your baby have some quiet time to play. It’s an important developmental task for babies to learn to play in your presence, but not with you. This is a first step towards self-initiative, mastery, and learning to entertain themselves. I’m not suggesting that you leave her to cry, but that you meet all her needs, and then try putting her down to let her explore and play. If she cries, comfort, engage a bit and then back off, but stay present. This lets you turn your attention to your other children, and it’s good for the baby as well. As Magda Gerber, author of Your Self-Confident Baby, says, ‘Respect your child … (and make life easier) by not “teaching your child to play” … You are simply available to your child without inflicting on her your desires in regard to what she should be doing or how she should be doing it.’3

3. Seize any quiet moments to connect. Every child needs to feel seen, heard, and appreciated – not 24/7, but certainly every single day. When one child is busy playing, even briefly, resist clearing up the kitchen. It’s a perfect time to go sit with the other child. Don’t interrupt his play. Just watch, and pour your love and attention into him. If he looks up, comment (without evaluation) so he knows you’re really taking him in: ‘It can be hard to get the tracks to hold together,’ or ‘You’re doing the outside edges of the puzzle first.’ You’ll be amazed how he relaxes and soaks in all that love, and carries it with him in the form of agreeableness throughout the day.

4. Build time with each child into the routine. It’s fine to share your attention among more than one child most of the day. That’s what it means to live in a family. But be sure that each child can count on having you all to herself every single day for a short time. Try for Special Time (see ‘Preventive Maintenance’ here) with each child daily. If Special Time is mostly on weekends, be sure your child can count on a loving chat while you gently plait her hair every morning and a fifteen-minute snuggle and chat at bedtime.

5. Be present. Don’t multitask when you finally get one-on-one time with your child. Five minutes of your full attention is worth an hour of your partial attention. Put your phone away. Forget the laundry for now. Get down on your child’s level and make eye contact so he knows you’re listening only to him. Bored? That’s because you’re not fully present. Try just appreciating your child. Notice the curve of his cheek and the smell of his hair. When we really let go of everything else and just notice the fullness of the present moment, we don’t feel bored. In fact, once you give yourself permission to do this on a regular basis, you may find a whole new dimension to life.

6. Don’t shortchange the well-behaved child. It’s very common for a child to demand less attention than her siblings and get overlooked, until she starts to act out. All kids deserve Special Time with you, not just the one who’s more challenging. During time periods when one child requires more focus than another, be sure to connect with the other child with a hug, just to check in.

7. Rely on grandparents, if you’re lucky enough to have them. Once your child is able to sleep over happily with grandparents (or a trusted friend), use those times to have special dates with your other child.

8. Whenever possible, use prevention. All siblings get irritated at each other from time to time. When children are tired, hungry, or cranky, their prefrontal cortex has a hard time controlling their emotions. Luckily, we can usually see the storm brewing, and step in to prevent it, if we aren’t too stressed out to notice the warning signs. Gather the cranky child (or children) on to your lap for a preemptive time-in and refill that empty cup. Time-consuming? Yes, but so much better than dealing with the fight once they start lashing out at each other.

How to Help Your Older Child Solve His Problems with the Little One

When my daughter was two, her brother was born. We talked about how she already knew how to share, and not to knock down block towers, compared to what babies like to do, such as knocking down towers or taking things without asking. After that, when her brother would do something that would frustrate her, she would look at us and say, ‘That’s just what babies do!’ She would actually chuckle at him sometimes.

– Natasha

So far in this book, we’ve stressed meeting your child’s needs for connection and attention, so he doesn’t develop a chip on his shoulder towards the baby. But with most children, that’s not quite enough. You also have to help your child develop the skills to express his needs and problem-solve. Why?

Because the baby creates problems for him, from snatching his toys to shrieking loudly to pulling his hair. Your child needs to know what to do to solve the problem, or he’ll do what all humans do when attacked – go into fight, flight, or freeze mode. And since your child is bigger than the baby, fight will be at the top of his list.

Here are the five basic steps of problem-solving that you’ll use daily to help your child cope with the problems that arise from having a younger sibling.

1. Calm, empathize, and give your child the words to express his needs. When children are upset, ‘use your words’ isn’t enough – they need to know what words to say. ‘It’s okay, sweetie, you don’t have to yell at him … I know he’s being very loud and it hurts your ears, but yelling won’t help him stop shrieking … You can just say, “Please don’t shriek, it hurts my ears … I hear you want a car!”’

2. Model calm problem-solving. ‘You’re worried that he’s touching your cars … don’t worry, it’s not an emergency … I will help you … We will work this out together.’ Your backup helps him to calm down so he moves out of fight mode and can think more clearly.

3. Help your child learn to ‘not take it personally’ by describing the problem. ‘You’re upset that he wants to play with your cars? You want them all to yourself right now, but he keeps grabbing at them?’ Notice you aren’t making anyone wrong. You may think it’s obvious that your child should simply share one of his fifteen cars, but they’re his, and he clearly wants them all right now. Putting him on the defensive will just increase his feeling of being threatened and make it even less likely that he’ll decide to share. So refrain from judgement, and simply state the disagreement as a problem to be solved.

4. Invite him to help problem-solve. ‘Hmm … You want to play with all the cars yourself … And he really wants a car … I wonder what we could do to solve this?’ You aren’t making him solve it himself, but you’re helping him start to take responsibility to think about solutions. Remember that if you push a certain solution (‘Just give him a car!’), your child feels pushed around and gets resistant.

5. Help your child come up with solutions. As they gain experience with this process, even two- and three-year-olds come up with solutions. In the beginning, though, you may need to help. ‘Let’s see, do you think he’d like to play with the train engine instead? Want to offer it to him? Gently, now …’

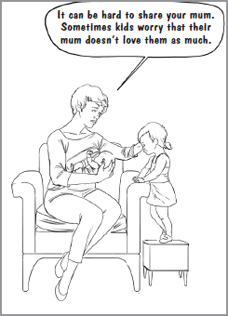

What to Say When Your Child Is Jealous of the Baby

When children feel understood, their loneliness and hurt diminish and their love for their parent is deepened. A parent’s sympathy serves as emotional first aid for bruised feelings. When we genuinely acknowledge a child’s plight and voice her disappointment, she often gathers the strength to face reality.

– Haim Ginott, author of Between Parent and Child

If you work to stay connected to your child, she probably won’t have too many moments where she feels unbearably jealous of her new sibling. You can be sure, though, that she’ll have some. Make sure she knows that these feelings are completely normal, so that she doesn’t feel like a monster. Acknowledge how hard it is for her and give her permission to grieve. See if you can offer some hope that things might feel better in the future, without discounting her distress.

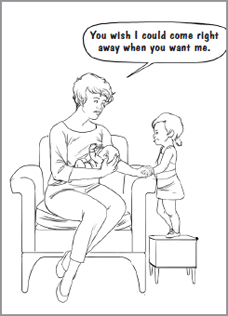

‘DO YOU EVEN CARE ABOUT ME ANY MORE?’

‘Oh, sweetie, I love you so much … I could never love anyone more. You are my one and only Aliyah and there is no one like you in the whole wide world. I feel so lucky to be your mum. Are you feeling like I don’t care? I guess I have been very tired, and super busy, so it has been hard to show you my love in the ways I used to. I have more than enough love for both you and your sister. I’m sorry that you have felt not cared about. Let’s find a way to make things better. I think we need some Aliyah and Mummy time today while the baby naps. What would you like to do with our Special Time together today?’

‘IT’S NOT FAIR; YOU NEVER HELP ME. I NEED HELP, TOO!’

‘Does it seem like my hands are always too busy with the baby to help you? That must feel so unfair! It’s hard to wait, I know. I know you need help, too, and I will always be here to help you when you need me. I will try to do a better job noticing when you need help. But I’m not perfect, so I won’t always notice. Can you tell me when you need help, with your words?’

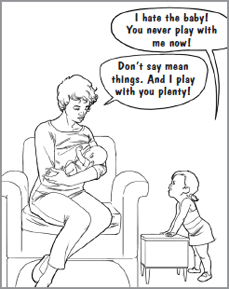

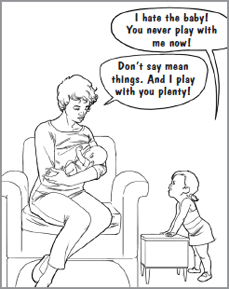

WHEN YOUR CHILD IS JEALOUS …

Instead of Denying Her Feelings |

Try Connecting |

|

|

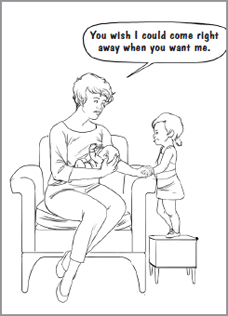

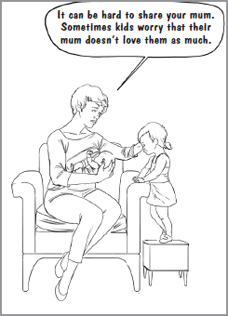

It’s natural to get defensive. Instead, take a deep breath and see it from her perspective. |

Empathize and describe the problem. |

|

|

|

Acknowledge longings and give her her wish in fantasy. |

Acknowledge her deeper feelings. |

|

|

|

Reassure her. |

Fill the need the child is expressing. |

‘I HATE HAVING A BABY!’

‘It’s hard sometimes, having a baby in the house. I guess it makes you very angry sometimes to have to share me, and to have to be quiet so he can sleep, and to have to wait your turn … It can be very hard, can’t it? You can always tell me when it’s hard, and I will always understand, and help you.’ (Think the word ‘hate’ calls for a tougher response? See ‘When Your Child Says He Hates His Sibling’ here.)

‘I MIGHT AS WELL BE DEAD!’

Don’t panic. He’s choosing the most powerful word he knows to show you know how miserable he is. Don’t argue with him. Instead, empathize and offer comfort: ‘Sometimes you feel that bad, huh? Oh, sweetheart, I am so sorry it’s so hard … Come here and let me hold you.’ Hopefully, then, he’ll cry. If he resists, he’s using his anger as a shield for all that pain. Prioritize preventive maintenance and rebuilding your connection with him so that he feels safe enough to show you those feelings. The more you can soften your heart, the more he’ll soften his, and the faster healing can begin.

What to Do About Toy Grabbing

Most older siblings grab toys from the baby. After all, anything the baby has suddenly looks pretty enticing to an older sib. But is grabbing toys always about sibling rivalry? No. Toddlers are just developing social skills, and taking toys can be a clumsy attempt to ‘relate’ to a sibling. Babies generally don’t mind when another child takes something from them, so when the toy grabbing is sporadic, there’s no need to intervene.

But there’s a reason ‘taking sweets from a baby’ has come to symbolize an easy but immoral abuse of power. Parents usually feel uncomfortable when their child begins to compulsively grab from the baby because the baby is defenceless, unable to express his needs. Constant grabbing isn’t good for the baby – who, after all, is exploring that toy – and it’s actually not good for the other child either, because compulsive behaviour of any kind is a red flag that your child needs help with the emotions driving it.

1. If both kids are laughing, don’t spoil the fun. The baby might be more interested in the game with big sister than in hanging on to the toy. The lesson you’re trying to teach will be lost, because this is a game, not toy snatching by your eldest.

2. Describe what happened. ‘Baby was shaking his rattle so hard and laughing … Zack wanted to try the rattle, too … Now Zack has the rattle … Baby looks surprised … Now Zack shakes the rattle … shake shake shake … Baby laughs and laughs … Zack laughs, too … Now Baby has the giraffe … He’s trying to put it in his mouth … Now Zack takes the giraffe … Baby looks surprised.’

Why describe in such detail? Because your toddler isn’t actually aware of what he’s doing and what effect it has on his brother. He’s just feeling an impulse and following it. Your words help him develop self-awareness. And while your eleven-month-old isn’t quite sure yet what you’re saying, he knows you’re acknowledging him, which matters.

3. Empathize, and ask questions to build empathy. ‘That rattle sounds pretty great, doesn’t it? You want to shake it, too … The baby looked surprised when you took the rattle … I wonder if he was done with his turn? … What do you think he would say if we asked him?’

4. Teach your child to offer ‘trades’ to the baby. But how do you know whether the baby is done with his turn? Ask the baby, using the baby’s language: action. ‘You want the rattle? I wonder if the baby is done with it? Why don’t you bring him a different toy, to see if he’s ready to swap? That way, you’ll know if he’s finished with his turn.’ Most of the time, the baby will happily switch toys. He’ll probably think it’s a game. That’s fine. This lays the groundwork so that when the baby starts to resist swapping, your child will be prepared to respect the baby’s right to a longer turn.

5. If your child can’t respect the baby’s turn and keeps grabbing, it isn’t actually about the toy. Compulsive behaviour of any kind signals a deeper unmet need or feeling we can’t verbally express. In other words, if your child ‘always’ grabs whatever the baby is holding, then he has some big feelings that are driving him to compulsively take whatever he can get from his sibling. The likeliest hypothesis is that he’s feeling forced to share far too much with this baby, including his parents, and he’s feeling desperately needy. The best way to help your child process those big feelings is with a scheduled meltdown (see Chapter 2).

As always, you move into a scheduled meltdown by setting a compassionate limit. When your son starts to grab from the baby, put your hand on the toy to stop him. Say, ‘I see you want that … It’s still the baby’s turn … Your turn will be next … I’ll help you wait.’

If he’s already snatched the toy, the limit is to ask him to give it back. Get down on the floor next to your child and put your hand on the toy. ‘Hey, sweetie – it looks like the baby is upset. It was still his turn and he wasn’t ready to give you the toy yet. Want to try a trade? Hmm … it looks like he doesn’t want anything else, just that toy. Time to give it back now. When he’s finished with his turn, he’ll give it to you.’ Should you snatch the toy from your child? No. But if your hand is on it, he’ll either give it to you or start to cry while clinging to it. Before you know it, he’s showing you all those tears and fears that are driving him to grab from the baby in the first place. (See ‘Scheduled Meltdowns’ here and ‘Rethinking Sharing’ here.)

When Your Child Is Aggressive Towards the Baby

If your child hurts the baby, naturally you’ll be furious. You’ll feel an urgent need to teach him a lesson, and you’ll probably want to hurt him back, even if you stop yourself from doing so. It will be hard to see his perspective. But consider how you would feel if your partner suddenly seemed smitten with someone new. You might lash out, too. Any child who hurts the baby is suffering from a broken heart. He needs your help to heal it.

Henry, age three, is playing with Sophie, eleven months, by grabbing a toy away from her. Sophie loves his attention and giggles at this interesting game, especially because he restores the toy to her every time. But Henry is getting rougher each time, and Sophie is clinging harder to the toy. He wrenches it away from her. Sophie bursts into tears. Henry, feeling guilty, says, ‘You act like a baby!’ and reaches out and shoves her down, hard. Now Sophie is wailing.

If Dad had noticed the game getting rougher, he could have intervened by getting between the kids and engaging in the game: ‘Hey, what about me? Take the toy from someone your own size, why don’t you? Waaaaaa … You took my toy!’ There would have been giggling all round, giving Henry the opportunity to discharge some tension around having to ‘share’ everything in his life with his sister. But Dad, being human and a parent, was trying to do three other things and simply glad for a moment of quiet. What should he do now?

Punishment of any kind will make Henry feel worse and act worse. (See Chapter 2 and Chapter 5.) Helping him with the feelings that are driving his aggression is what will stop the hitting. But that doesn’t mean we don’t set a firm limit against violence.

First, Dad scoops up Sophie, who is howling. He resists the urge to yell at Henry. In fact, he resists interacting with Henry at all until he can get himself a bit calmer. So he summons up his nurturing and focuses on Sophie, which helps shift him from his murderous don’t-you-mess-with-my-baby self to his nurturing-parent self.

Dad: Ouch! That hurt! (Sophie nods, crying hard.) Getting pushed can hurt your body, and your feelings, too! … Tell me about it, Sophie.

Sophie cries even louder for a moment, as we all do when we’re hurt and receive loving attention. Soon, though, she recovers and reaches for the toy, which is abandoned on the floor. Dad puts her down with the toy, takes a deep breath to calm himself, and turns to Henry. He knows Henry is feeling frightened, and no learning will happen in that state, so he tries to be warm and matter-of-fact, not accusatory.

Dad: That hurt your sister, didn’t it?

Henry: I guess. She’s a crybaby.

Dad doesn’t take the bait. He gets down on the floor next to Henry, making eye contact. He’s breathing deeply, working to stay calm and kind. Naturally, his face is serious.

Dad: Well, everybody cries sometimes. Sophie certainly cries when she gets hurt, like the rest of us. What happened, Henry?

Henry: She wouldn’t give me my toy.

Henry looks blank. Is he remorseless? No. He feels ashamed, and afraid of what Dad is about to say. He’s in ‘fight, flight, or freeze’ – in this case, freeze. So it looks on the surface as if he doesn’t feel anything.

Dad: That was your toy, and you wanted it. (He is empathizing.)

Henry nods but doesn’t say anything.

Dad: You must have been really upset to hurt her … I’m sorry I wasn’t here to help.

Is Dad blaming himself? No. He’s modelling taking responsibility. That opens the door a bit for Henry to feel less defensive. He shoots a quick look at Dad – Is it possible that he might understand? – and then looks away again.

Dad: I hear you were frustrated with her. But hitting hurts. I won’t let you hit your sister.

Henry glazes over and looks away. Dad knows Henry’s trying to push away some big feelings that he needs help with. Dad moves in close, pulling Henry gently against him.

Dad: Sometimes you get really mad at your sister, don’t you?

Henry (looking at him, testing): I hate her.

Dad (ignoring the hate bomb): Sometimes you get so mad it feels like you hate her. (Trying to go under the anger to the more vulnerable feelings that drive it.) I know you tell me it isn’t fair that she always gets to sleep with us. Maybe you think she gets everything, and you get left out?

Henry (shouting): I am left out! Why did you have to get a baby anyway?! You never have time for me any more! Why can’t you send her back?! She ruins everything!

Dad: You miss the way it used to be.

Henry bursts into tears and buries his head in Dad’s shoulder. As he sobs, Dad says, ‘You can cry as much as you need to. I am right here. I am ALWAYS here for you, no matter what, baby or no baby.’ He isn’t trying to stop Henry from crying. He’s helping Henry feel safe enough to show him all that pain.

Sophie is initially distressed by Henry’s crying, so Dad does the hardest part of this process – reassuring her and keeping her out of reach of Henry’s flailing feet at the same time as he tends to Henry. He has one arm round each child.

Dad: It’s okay, Sophie. Henry’s just sad right now.

Finally, Henry has finished crying, and snuggles on Dad’s lap. Sophie has wandered to the train track across the room and is happily chugging the trains round, no longer listening.

Dad: You know that I couldn’t love anyone more than you, right? You are the only Henry I have and you have the only Henry place in my heart. You are my Henry and I am your dad and I will always love you, no matter what.

Henry nods.

Dad: I know you worry sometimes that we love Sophie more. But that is never true. No matter how much love we give your sister, there is always more than enough for you. You can always tell me if you’re feeling left out, or angry, you know that.

Henry nods again.

Dad: What about hitting?

Henry: It’s bad.

Dad: Well, what happens when you hit?

Henry: I get in trouble.

Dad: What else?

Henry: Sophie cries.

Dad: Why does she cry?

Henry: Because it hurts.

Dad: And how do you feel inside?

Henry (looking away): Bad.

Dad: Yes, Henry. You feel bad, because when we hit, it hurts the other person, and it also hurts our own heart. People are not for hitting. People are for loving. Just like your mum and I love and hug you. So what can you do instead of hitting your sister when you feel like hitting?

Henry: Get you?

Dad: Yes, use your words and tell me. If you need help with your feelings, or to protect your toys, call me and I will always help you. What else?

Henry: Give her a different toy?

Dad: Yes, what a great idea! And if you’re really mad, could you turn round and hit the sofa?

Henry: I guess so. But what I really want is one of those punch bags. It falls over.

Dad: You mean instead of your sister?

Both Dad and Henry start laughing.

Is this mean? I don’t think so. It defuses the tension. Sophie isn’t listening. And Dad quickly restates the limit.

Dad: That’s a good idea. Punch bags are made for falling down. Little sisters are made to love. Let’s consider a punch bag. But for now, I think you have a little repair work to do with your sister. What could you do to help her feel safe with you again?

Henry: I could hug her.

Dad: I know she would like that, if you were gentle. Would you like that?

Henry: Yeah. Sometimes she’s okay. For a baby.

Is it necessary to make Henry feel bad about what he did? No. He knows it was hurtful; he just couldn’t help himself in the press of all these hateful feelings. Yelling, punishing, time-outs, and giving him the cold shoulder would all make him feel worse, convincing him that his parents don’t love him any more, no matter what they say. In that case, why not just make his sister’s life miserable?

Instead, what does Dad do?

WHEN CHILDREN HIT …

Instead of Punishing |

Try Prevention |

|

|

Kids hit when they don’t know how else to express their feelings. Punishment doesn’t help kids with their upsets; it makes those hurts and fears worse. |

When possible, prevent hitting. Acknowledging feelings helps kids manage their emotions so they don’t have to act on them. |

When Prevention Fails |

Prevent Future Hitting |

|

|

First, tend to the child who’s hurt. Don’t interact with the child who did the hitting until you can do so calmly. |

Empathize while you reinforce your limit. |

|

By Helping Kids with Feelings |

|

|

Acknowledge his point of view. |

Once he’s calm and connected, guide him to problem-solve to prevent future hitting. |

1. Gives Henry the message that while actions must be limited – hitting hurts and is not allowed – all feelings are acceptable.

2. Helps Henry ‘express’ the emotions that have been eating at him and driving his aggressive behaviour, so those feelings can begin to evaporate. This melts the armour that’s been collecting around Henry’s heart, so he feels less angry at his sister, and more cooperative in general.

3. Reconnects with him, so Henry knows he’s valued, not displaced.

4. Reassures Henry that he can tell his parents how he feels and get help. He isn’t left on his own in his struggle to control himself so he doesn’t hurt his sister.

5. Helps Henry notice that hitting not only hurts his sister – but hurts his own heart, too.

6. Builds Henry’s capacity for self-reflection, which will help him to manage himself in the future.

7. Builds Henry’s empathy for his sister by focusing on hitting being a hurtful way to interact with another person, rather than simply labelling it as a bad act.

8. Helps Henry imagine other ways to handle his feelings in the future. Henry is open to this because he wasn’t made to feel like a terrible person, which would have put him on the defensive.

9. Empowers Henry to ‘repair’ his relationship with his sister.

10. Helps Henry laugh about the situation, which discharges fear and helps Henry understand that feelings aren’t permanent – they can be expressed, and then we feel better. This jump-starts the healing process inside Henry.

11. Helps Henry past his anger to an emotionally generous state where he can acknowledge that he has good feelings about his sister.

Maybe most important, Henry learns that he has a father who loves all of him, no matter what. That’s what will gradually form the core of an unshakable internal happiness that will allow him to handle whatever life throws at him – including, eventually, being a great big brother.

For more on handling hitting, see ‘Should You Punish Your Child for Aggression?’ here.

What If the Aggressor Is Too Young to Understand?

In general, young children learn language faster if you use fairly normal language, not baby talk, with them. Remember that receptive language is always well ahead of expressive language, so babies and toddlers can understand much more than we think. But since parents often tell me they want words that a little one who isn’t verbal yet can understand, here’s a version of what the dialogue above might look like with a young toddler.

1. Describe what happened. ‘You hit Amelia. Ouch! Hitting hurts. Amelia cried … You were MAD!’

2. Empathize. ‘Amelia pulled your hair. Ouch! You were hurt and mad!’

3. Help your child come up with options for next time. ‘No hitting. Hitting hurts. Can you call me for help? Say MUMMY! Call me now … That’s right. See, I’m coming. Here I am!’ Pick your child up for a big hug and get him laughing, which creates a positive association to calling for you when he’s in an altercation with the little one. (See the ‘Mummy, I Need You!’ game in ‘Using Games to Help Your Child with Jealousy’ here.)

4. Help your child repair the relationship. ‘We touch gently like this, gently … See, she’s smiling at you!’

What If It’s the Baby Who’s Aggressive?

As babies get older, they’re not exempt from sibling rivalry. Your little one may very well feel worried, at times, that his siblings might keep him from getting what he needs.

1. Model for your little one how to offer trades to the older child. Clue in the older sibling so she understands what’s going on and will take the trade sometimes, so the younger child learns how to do it and feels empowered to initiate. Of course, there will be times when the older child has no interest in the trade, and the younger one howls. You’ll need to step in and commiserate with how hard it is, but of course, respect your older child’s right to say no.

2. Empathize. When your fifteen-month-old tries to push his older sibling out of your lap, acknowledge his feelings. ‘You want to be in my lap, don’t you? You don’t want Justin in my lap.’

3. Protect your older child’s rights by setting a limit, while finding a way to meet the younger child’s need as well. ‘Justin is reading with me … He’s going to stay right here. You can come up on my other side and read with us.’

4. Expect the little one to be unhappy. Most of the time, a fifteen-month-old will howl when he doesn’t get his way. But what he really wants is to be reassured of your love. So as long as you offer him that, he’ll stop attacking his brother. After all, big brother is only a problem if he’s in the fifteen-month-old’s way. So scoop him up and snuggle him in your other arm, all the while assuring both kids that you have enough arms for both of them. Then divert his attention to the book you’re reading with your older child, so everyone settles into a cozy feeling again. ‘Everyone wants Mama … Don’t worry, Mama can hold you both. Look at this picture! The baby bear wants his Mama, too!’

What do your children learn from this? They both matter and you’ll respond to both of them. As your littlest gets older, you’ll have lots of opportunity to help him with his sibling jealousy. (Also see ‘When Your Toddler Is the Aggressor Against Your Older Child’ here.)

Games to Help Your Children Bond with the Baby

Your baby isn’t quite ready for rough and tumble, but there are ways to support her ‘playing’ with her big sibs. Try these ideas to get started. You’ll all laugh so much, you’ll be inspired to come up with more ideas of your own.

• Use your little one as a ‘rugby ball’ – run her round the rest of the family into the end zone. Your kids will love it.

• ‘I play a game where I hold our baby [three months] and we chase her big sisters [three-year-old twins], until we catch them for a cuddle. The baby starts giggling in anticipation and always smiles at her sisters, which in turn gets her sisters giggling as well. The big girls know they have to be very gentle with the baby.’ – Jessica

• Be a baby ventriloquist. Be the voice for the baby and have him say all kinds of funny things to his siblings. Be sure that he also says tender, grateful, and admiring things.