Following the collapse of Enron, WorldCom, and several other major multinational companies, the capital markets experienced the Era of Accountability 1.0, which included the passage of Sarbanes-Oxley (Sarbox) in 2002. Sarbox brought new standards for conduct and governance for public-company boards of directors and officers, new and more stringent reporting requirements, stronger internal controls, and stiffer penalties for noncompliance. It also influenced the focus and depth of M&A due diligence standards, which began to take deeper dives into issues of financial reporting, objectivity, and verification. This is discussed further in the appendix to this chapter.

Less than a short seven years later, we entered the Era of Accountability 2.0. The election of Barack Obama and the Obama administration’s commitment to transparency; the role of government in bailouts, including TARP; the failure of banks and automobile companies; the Madoff scandal; the severe global recession; and mistrust of Wall Street collectively contributed to an increase in staffing at the SEC, the expectation of vigorous government enforcement activities in a variety of areas, and the possibility of new generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) standards. These evolving developments, in turn, are elevating, expanding, and refining the portfolio of due diligence best practices in M&A, financing, and other core business transactions. By 2017, the Era of Accountability had matured and expanded into heightened levels of transparency driven by social media, increased shareholder activism, and boards being held more accountable for botched or ill-fated transactions.

I am not implying that graduation from 1.0 to 2.0 involves a tectonic shift in due diligence best practices. M&A practices and documentation generally are continuing to evolve in small increments. There are occasional exceptions, such as the fairly rapid and widespread move to electronic data rooms. And responses to sweeping legislative and regulatory developments are necessarily fast-paced. The adaptation of acquisition agreements and processes to the preacquisition notification requirements of the U.S. Hart-Scott-Rodino Antitrust Improvements Acts of 1976 is a notable example. Government intervention over the years, triggered in large part by excesses that exploited a flawed regulatory regime, has been so sweeping, fueled by intense and enduring public outrage, that due diligence best practices inevitably will respond to the challenges of a more highly regulated economy in which buyers and sellers must live under the microscope of vigorous government enforcement and intense public scrutiny. This response in large part should encompass a reaffirmation of existing best practices. Accordingly, much of the following discussion emphasizes those practices prevailing in the Era of Accountability 1.0. Although the anticipated changes in practices are likely to be incremental, in the context of ever-expanding government regulation and enforcement activities, the new environment merits a 2.0 designation.

First, we must embrace the notion that due diligence is both an art and a science, and that it is a process, not an event. Due diligence in this new era requires an increasingly creative and strategic approach, not just a mechanical methodology. Due diligence in M&A requires a deep dive into the history, mission, values, culture, and intangible assets of the company, rather than a mere formalistic review of key contracts and corporate housekeeping documents. Due diligence must be focused on avoiding the “failure” characterization assigned to 30 to 70 percent of all M&A transactions, based on post-closing metrics that include reduced shareholder value.1 Businesses, large and small alike, that are continuing to cope with the current economic shipwreck surely must avoid foundering again on the rocks of failed M&A endeavors. Lawyers, accountants, investment bankers, industry specialists, and strategic consultants must reaffirm existing best practices and commit themselves to higher and more inquisitive standards of due diligence conduct in the Era of Accountability 2.0.

The due diligence process involves a legal, financial, and strategic review of all of the seller’s documents, contractual relationships, operating history, and organizational structure. Due diligence is not just a process; it is also a reality test—a test of whether the factors that are driving the deal and making it look attractive to the parties are real or illusory. Due diligence is not a quest to find the deal breakers; it is a test of the value proposition underlying the transaction to make sure that the inside of the house is as attractive as the outside. Once the foundation has been disassembled, it can either be rebuilt to support a deal that makes sense or left in a disaggregated state so that the buyer avoids the consummation of a transaction that is operationally, financially, strategically, or otherwise imprudent. It is also important to understand that in the Era of Accountability 2.0, due diligence typically will be more expansive and will probe more deeply than ever before. Accordingly, due diligence will take longer and be costlier, especially if the prospective buyer is a public company or a company with plans to go public within the next eighteen months.

A prime example of the need for heightened due diligence is provided by the articulated policy of the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) relating to enforcement of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA). At its most basic level, the FCPA prohibits U.S. and certain foreign companies from bribing foreign government officials. A discussion of the many pitfalls a buyer can encounter under the FCPA in acquiring a company that may have violated the FCPA is beyond the scope of this chapter. The FCPA is a strong example because the DOJ has issued written guidance effectively announcing that it is less likely to take harsh enforcement action against a company that purchases another company that has violated the FCPA if the buyer has (1) conducted extensive FCPA-oriented due diligence, (2) obtained certain representations and warranties from the seller, (3) made voluntary disclosures to the DOJ, and (4) implemented structural compliance safeguards.2 The DOJ guidance is very fact-specific and therefore is not generically applicable to all buyers facing potential FCPA issues. However, with an ever-increasing number of cross-border acquisitions in the global M&A marketplace, the current environment heightens the need for buyers who are examining certain foreign targets to undertake extensive FCPA due diligence.

Returning to the fundamentals of due diligence, the seller’s team must organize the documents and prepare the data room. Although electronic data rooms, which are especially important to cross-border M&A transactions, have improved the efficiency of the due diligence process, the seller still must commit substantial resources to assembling the documents. The buyer’s team must be prepared to ask all the right questions as it conducts a detailed analysis of the documents provided and prepares for in-person interviews and follow-on requests. To the extent that the deal is structured as a merger, or where the seller will be taking the buyer’s stock as all or part of its compensation, the process of due diligence is likely to be a two-way street as the parties gather background information on each other.

The due diligence work is usually divided between two working teams: (1) the financial and strategic team, which is typically managed by the buyer’s management team with assistance from its accountants, and (2) the legal team, which involves the buyer’s counsel with appropriate assistance from technical experts such as environmental engineers and export compliance specialists, depending on the nature of the target’s business. Throughout the process, both teams compare notes on open issues and potential risks and problems. The legal due diligence focuses on potential legal issues and problems that may prove to be impediments to the transaction. It also sheds light on how the transaction should be structured and the contents of the transaction documents, such as the representations and warranties. The business due diligence focuses on the strategic and financial issues in the transaction, such as confirmation of the past financial performance of the seller; integration of the human and financial resources of the two companies; confirmation of the operating, production, and distribution synergies and economies of scale to be achieved by the acquisition; and the collection of information necessary for financing the transaction.

Overall, the due diligence process, when done properly, can be tedious, frustrating, time-consuming, and expensive. For example, one FCPA due diligence effort cited in a DOJ opinion encompassed a review of at least four million electronic documents requiring nearly 45,000 hours of mostly lawyer time.3 Fortunately, many transactions will not require such an extensive effort. Yet, detailed due diligence is a necessary prerequisite to a well-planned acquisition, and it can be quite informative and revealing in its analysis of the target company and its measures of the costs and risks associated with the transaction.

Buyers should expect sellers to become defensive, evasive, and impatient during the due diligence phase of the transaction. Most business owners and executives do not enjoy having their business policies and decisions under the microscope, especially for an extended period of time, and will only tolerate so many rounds of nitpicking. Eventually, the seller is likely to give the prospective buyer an ultimatum: “Finish the due diligence soon or the deal is off.” When negotiations have reached this point, it is best to end the examination process soon thereafter to stay focused on a short list of bona fide concerns. Buyers should resist the temptation to conduct a hasty “once-over,” either to save costs or to appease the seller. Yet at the same time, they should avoid “due diligence overkill,” keeping in mind that due diligence is not a perfect process and should not be a tedious fishing expedition. Like any audit, a due diligence process is designed to answer the important questions and provide reasonable assurance that the seller’s claims about the business are fair and legitimate.

There are, of course, exceptions in which the buyer faces structural constraints on conducting thorough due diligence. These include acquisitions of bankrupt companies under Section 363 of the U.S. Bankruptcy Code. Although companies that are in Chapter 11 proceedings typically provide for some due diligence by prospective buyers who wish to submit bids, the representations and warranties that may be crafted in response to the buyer’s due diligence are somewhat less meaningful than in nonbankruptcy transactions because frequently there is no ongoing indemnification obligation on the part of the estate of the bankrupt seller.

In addition to the bankruptcy context, the increasingly common use of auctions managed by investment banks or other financial advisors has affected early-stage due diligence activities. While sellers typically permit interested bidders to examine data room documents and submit follow-on questions, full-scale due diligence generally is not permitted until the seller has selected the winning bidder following a review of the prospective buyers’ markups of a proposed acquisition agreement. Buyers frequently propose numerous additional revisions to the acquisition agreement based on their subsequent due diligence, but sellers often impose tight deadlines on the winning bidders and otherwise attempt to limit the due diligence–driven revisions to a bare minimum.

Whatever the type of transaction, there is always the possibility that critical information may slip through the cracks, which is precisely why broad representations, warranties, liability holdbacks, and indemnification provisions should be included in the final purchase agreement, at least in a nonbankruptcy context.4 These provisions protect the buyer, while the seller negotiates for carve-outs (e.g., a minimum “basket” of liabilities before the buyer may seek reimbursement for undisclosed or unexpected liabilities), exceptions, and limitations on liability that provide post-closing protections. To the extent that the seller is able to negotiate favorable limits on the seller’s liability, including the period during which the buyer may assert claims (referred to as the “survival” period for representations and warranties), the indemnification provisions may in fact benefit the seller more than the buyer. Likewise, sophisticated sellers will try to include a disclaimer in the acquisition agreement providing that the buyer is relying only on the representations and warranties in the four corners of the agreement. Such a clause frequently prevents a buyer from bringing fraud claims against the seller.5

The nature and scope of all these provisions are likely to be hotly contested in the negotiations. However, buyers should not become so preoccupied with the minutiae and emotion attending these negotiations that they lose sight of the big picture. Remember that the key objective of due diligence is not only to confirm that the deal makes sense (e.g., to confirm the factual assumptions and preliminary valuations underlying the terms by which the buyer negotiates the transaction), but also to determine whether the transaction should proceed at all. The buyer must recognize at all times that there may be a need to terminate negotiations if the risks or potential liabilities in the transaction greatly exceed what is anticipated and there is no effective way to insure against them or otherwise compensate the buyer for assuming such risks and liabilities.

As stated earlier, effective due diligence is both an art and a science. The art is the style and experience to know which questions to ask and how and when to ask them. It is the ability to create an atmosphere of both trust and fear in the seller that encourages full and complete disclosure. In this sense, the due diligence team is on a risk discovery and assessment mission, looking for potential problems and liabilities (the search) and finding ways to resolve these problems prior to closing and to ensure that risks are allocated fairly and openly after the closing.

The science of due diligence is in the preparation of comprehensive and customized checklists of the specific questions to be presented to the seller, in maintaining a methodical system for organizing and analyzing the documents and data provided by the seller, and in quantitatively assessing the risks raised by those problems that are discovered in the process. One of the key areas is detection of the seller’s obligations, particularly those that the buyer will be expected or required to assume after closing (especially in a stock purchase transaction or comparable merger; in an asset purchase, purchased liabilities are specifically defined, subject to a few successor liabilities that cannot be contractually avoided). The due diligence process is designed first to detect the existence of the obligations, and second to identify any defaults or problems in connection with these obligations that will affect the buyer after closing.

The best way for the buyer to ensure that virtually no stone remains unturned is through effective due diligence preparation and planning. Astute buyers typically employ comprehensive due diligence checklists that are intended to guide the company’s management team while it works closely with counsel to gather and review all legal documents that may be relevant to the structure and pricing of the transaction; to assess the potential legal risks and liabilities to the buyer following the closing; and to identify all of the consents, approvals, and notifications that may be required from or to third parties and government agencies. The most common form of third-party consent is that required in connection with existing contracts that cannot be assigned or otherwise transferred without the counterparty’s prior approval.

A due diligence checklist, however, should be a guideline, not a crutch. The buyer’s management team must take the lead in developing questions that pertain to the nature of the seller’s business. These questions will set the pace for the level of detail and adequacy of the review. The key point here is that every type of business has its own issues and problems, and a standard set of questions will rarely be sufficient. Some of the more common mistakes made during the process are set forth in Figure 5-1.

Figure 5-1. Common Mistakes Made by the Buyer

During the Due Diligence Investigation

1.Mismatch between the documents provided by the seller and the skills of the buyer’s review team. The seller may have particularly complex financial statements or highly technical reports that must be truly understood by the buyer’s due diligence team. Make sure that there is a capability fit.

2.Poor communication and misunderstandings. The communications between the teams of the buyer and the seller should be open and clear. The process must be well orchestrated.

3.Lack of planning and focus in the preparation of the due diligence questionnaires and in the interviews with the seller’s team. The focus must be on asking the right questions, not just a lot of questions. Sellers will resent wasteful “fishing expeditions” when the buyer’s team is unfocused.

4.Inadequate time devoted to tax and financial matters. The buyer’s (and seller’s) CFO and CPA must play an integral part in the due diligence process in order to gather data on past financial performance and tax reporting, unusual financial events, or disturbing trends or inefficiencies.

5.Lack of reasonable accommodations and support for the buyer’s due diligence team. The buyer must insist that its team be treated like welcome guests, not like enemies from the IRS! Many times, buyer’s counsel is sent to a dark room in a corner of the building to inspect documents, without coffee, windows, or phones. It will enhance and expedite the transaction if the seller provides reasonable accommodations and support for the buyer’s due diligence team.

6.Ignoring the real story behind the numbers. The buyer and its team must dig deep into the financial data and test (and retest) the value proposition as to whether the deal truly makes sense. They must ask themselves, “Does the real value truly justify the price?” The economics of the deal may not hold water once a realistic look at cost allocation, inventory turnover, and capacity utilization is taken into account.

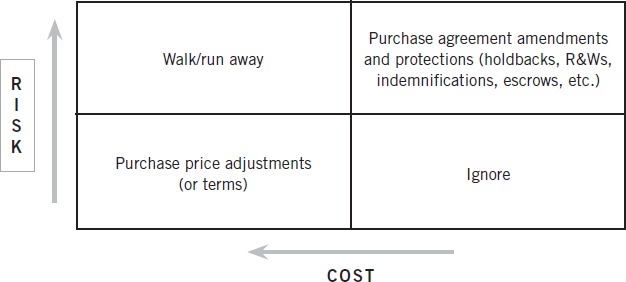

Figure 5-2. Dealing with Due Diligence Surprises

Due diligence surprises can come in varying shapes and sizes, each with varying degrees of severity, as described in Figure 5-2. Also, the current crisis of disengagement is impacting due diligence, as shown in Figure 5-3.

Figure 5-3. The Crisis of Disengagement and Its

Impact on Due Diligence

Our global economy is fighting an epidemic of alarming proportions. It is not cancer, intolerance, racial divides, terrorism, cyber-attacks, hunger, access to clean water, or the technology gap— although, unfortunately, all of those social epidemics remain firmly in place. Rather, it is a disease affecting the central nervous system of our economy—and it is destroying creativity, innovation, productivity, profitability, and overall enterprise value. This epidemic is a societal and workplace challenge costing hundreds of billions of dollars a year in the United States—a calamity so large that it could literally reverse the trend of our evolution if not soon corrected. It is the crisis of disengagement. And it is having a direct impact on corporate venturing, innovation, and the ability of a company to strategically harvest its intangible assets.

For example, in the United States, in the December 2016 update to Gallup’s State of the American Workplace, as well as in recent studies by the Conference Board, and many other prominent organizations, researchers have found that fewer than 30 percent of Americans are “somewhat satisfied” with their work and their career paths. The remaining 70 percent are “somewhat or highly dissatisfied,” citing inadequate challenge, pay, morale, sense of purpose, or lack of appreciation at the heart of their disdain. Many are bored, which eviscerates productivity and the ability to innovate, and in turn affects the profitability of companies and the ability to remain competitive in the world market.

Readers of this book—whether as intermediaries and investment bankers, principals or executives, corporate development teams, M&A lawyers, accountants and valuation experts—need to understand and embrace this disturbing trend in our workforce and deal with it in a wide variety of ways, from M&A structure, post-closing integration, strategic due diligence, valuation, fairness opinions, etc.—all of which may be affected by varying levels of employee or other types of disengagement.

Gallup 2016 State of the American Workplace Poll

31.5 percent of U.S. Workforce defines themselves as engaged.

31.5 percent of U.S. Workforce defines themselves as engaged.

51 percent are not engaged/disconnected.

51 percent are not engaged/disconnected.

17.5 percent are actively disengaged.

17.5 percent are actively disengaged.

It is hard to imagine that a disengaged workforce that spends the bulk of its time being distracted and dissatisfied will ever be a catalyst for the creativity and productivity in an enterprise or devote itself to driving long-term shareholder or enterprise value. It is equally hard to imagine an employee who feels disconnected and unappreciated spending time thinking about ways to be more efficient in his or her workplace, work with team members, or see new ways to improve the company’s current products and services. And it is harder still to imagine a disengaged manager spending the necessary time to figure out how to better engage employees.

Innovation within the organization (also known as intrepreneurship) refers to the actions and initiatives that transform organizations through strategic-renewal processes. Firms that consistently demonstrate durable corporate innovation are typically viewed as dynamic entities prepared to take advantage of new business opportunities when they arise, with a willingness to deviate from prior strategies and business models, to embrace new resource combinations that hold promise for new innovations. These companies tend to attract higher valuations in private financing, M&A transactions, strategic investments, and initial public offerings.

There have been numerous articles and books written over the years advocating the importance of “unleashing the entrepreneurial potential” of individuals by removing constraints on entrepreneurial behavior to drive enterprise value (see for example, Gary Hamel’s Leading the Revolution, Gifford Pinchott’s Intrapreneuring, and my 2012 book Harvesting Intangible Assets). Employees engaging in entrepreneurial behavior are the foundation for organizational innovation. In order to develop a culture of “corporate innovation,” organizations must establish a process through which individuals in an established firm pursue entrepreneurial opportunities to innovate without regard to the level and nature of currently available resources. However, keep in mind that, in the absence of proper control mechanisms, firms that manifest corporate-innovation activity may “tend to generate an incoherent mass of interesting but unrelated opportunities that may have profit potential, but that don’t move [those] firms toward a desirable future.”

Research also shows that engaged workers are more likely to foster a collaborative and innovative atmosphere among fellow employees by reacting positively to creative ideas of others on their team. A good example of this is Google, which fosters a variety of channels to enhance employee engagement through connectivity and the sharing of ideas. Some of the avenues for expression that the company facilities include having Google Cafes, which serve as venues for individuals to interact across their regular team, or Google Moderators, a management tool that was created to allow anyone within the company to posit questions they would like to have answered. Through the Moderator channel, employees can view existing ideas, questions, and suggestions. This generates a symbiotic relationship between innovation and employee engagement creating an inertial atmosphere.

For decades, workers were expected to know their jobs, do their work, keep their heads down, and only “bother” management with questions to avert a crisis. If a problem arises, know how and when to solve it, and don’t interfere with the supervisor’s valuable time. That mantra needs to shift if we are going to improve engagement in a way that will drive more innovation and upticks in shareholder value. Employees at all levels need to be liberated to ask the “whys?” and the “what ifs?” They need to be able to ask (without retribution or punishment), “Why am I doing my job the way I am doing it?” “Is there a better way?” “What would it take to change and why?” Empowering your teams to ask questions also demonstrates humility by the leadership team by admitting that they don’t know all the answers, and it gives permission to the workforce to begin to organize its thinking around the unknowns instead of the knowns, which will foster greater creativity, innovation, and productivity.

There are already a wide variety of human capital challenges in M&A transactions, ranging for a complex web of federal/state/local employment laws and regulations, compliance issues, union laws, retirement and compensation issues, general cultural issues, succession planning, leadership and governance, and the impact of automation and robotics as we begin to contemplate the workplace of the future.

This recently recognized crisis of disengagement raises new and more granular challenges in M&A, private equity, and strategic or venture financings due diligence. Nobody wants (or intends) to invest in or buy a company with a distracted, dysfunctional, or disengaged workforce. And no company will ever reach its full operational potential or maximum enterprise valuation with apathetic and disconnected workers.

Post-closing synergies and integration success are also highly unlikely when one or more of the buyer or seller’s human capital assets are grossly underperforming or feeling deeply underappreciated and focused on almost anything but their core tasks at hand. Leadership and governance teams on both sides of the transaction as well as their advisors are often either in denial as to the extent of the problem or lack the strategic tools to remedy the key challenges.

Sellers engaged in pre-transaction “mock” due diligence exercises need to be prepared for this new category of due diligence questions surrounding levels of engagement, and buyers and their advisors need to develop strategic due diligence skills around those concerns. Not too far down the road, activist shareholders and other affected third parties could possibly bring legal actions against leaders of buyers and sellers who ignore the importance of employee engagement levels and overall cultural performance in their due diligence and analysis of transactions and where mergers and acquisitions are underperforming on a post-closing bases as a result of this crisis.

What Role Can M&A Principals and Advisors Play?

Strengthen your HR/cultural-related due diligence analytical skills and approaches.

Strengthen your HR/cultural-related due diligence analytical skills and approaches.

Bring in Subject Matter Experts (SMEs) and specialists as needed.

Bring in Subject Matter Experts (SMEs) and specialists as needed.

Focus on these issues in pre–due diligence mock reviews.

Focus on these issues in pre–due diligence mock reviews.

Understand the connections between high levels of disengagement and the impact on other aspects of the business model operations (e.g., customer service, innovation, recruitment, brand, social media, etc.).

Understand the connections between high levels of disengagement and the impact on other aspects of the business model operations (e.g., customer service, innovation, recruitment, brand, social media, etc.).

Work with legal counsel with strong L&E skills and strategic understanding of disengagement issues.

Work with legal counsel with strong L&E skills and strategic understanding of disengagement issues.

Closely examine the alignment of reward/compensation systems with workplace performance and engagement.

Closely examine the alignment of reward/compensation systems with workplace performance and engagement.

Advise buy-side engagement clients on the risks of acquiring low-engagement companies.

Advise buy-side engagement clients on the risks of acquiring low-engagement companies.

Look for disengagement “warning signs” in due diligence on the seller (i.e., dysfunctional leadership, high turnover rates, an excess of negative social media posts on job-related or other websites/platforms, lack of succession planning or obvious turfmanship/protectionism in leadership positions, declining rates of profitability, lack of innovation, etc.).

Look for disengagement “warning signs” in due diligence on the seller (i.e., dysfunctional leadership, high turnover rates, an excess of negative social media posts on job-related or other websites/platforms, lack of succession planning or obvious turfmanship/protectionism in leadership positions, declining rates of profitability, lack of innovation, etc.).

Challenge buyers who think they have the “magic elixir” for curing cultural or employee performance defects on a post-closing basis (“Oh, this won’t be a problem once we buy them.” “Yeah, right!?”).

Challenge buyers who think they have the “magic elixir” for curing cultural or employee performance defects on a post-closing basis (“Oh, this won’t be a problem once we buy them.” “Yeah, right!?”).

For example, I worked on a deal that involved the purchase of a hockey league in the Midwest. It was easy to prepare the standard due diligence list and draw up questions regarding corporate structure and history, the status of the stadium leases, and team tax returns, and to question the steps that had been taken to protect the team trademarks. The more difficult task was developing a customized list. In my role as legal counsel, I asked my client the question, “If you were buying a sports league, what would you need to review?”

As stated earlier, every type of business has its own issues and problems. The list for this client included player and coaching contracts, stadium signage and promotional leases, league-wide and local-team sponsorship contracts, the immigration status of each player, team and player performance statistics, the status of contracts with each team’s star players, scouting reports and drafting procedures, ticket sales (including walk-up, advance, season, group tickets, and coupons) for each team and game, promotional agreements with equipment suppliers and providers of game-day merchandise, food and beverage concession contracts, the status of each team’s franchise agreement, commitments made to cities for future teams, and unique per-team advertising rates for dasher boards (the signs for advertising that surround the rink).

When done properly, due diligence is performed in multiple stages. First, all the basic data are gathered and specific topics are identified. Follow-up questions and additional data gathering can be performed in subsequent rounds of due diligence; they must be custom-tailored to the target’s core business industry trends and unique challenges.

The legal due diligence checklist in the following section is intended to guide the company’s management team while it works closely with counsel to gather and review all legal documents that may be relevant to the structure and pricing of the transaction; to assess the potential legal risks and liabilities to the buyer following the closing; and to identify all of the consents and approvals, such as an existing contract that can’t be assigned without consent, which must be obtained from third parties and government agencies.

Following the high-level suggestions in this overview of M&A due diligence best practices will not ensure that the parties to a transaction have successfully negotiated the rapids of the Era of Accountability 2.0. However, compliance with the best practices will go a long way toward keeping their transaction from joining the ranks of failed M&A deals that have plagued the economy in recent years.

In analyzing the company for sale, the buyer’s team carefully reviews and analyzes the following legal documents and records, where applicable.

A. Corporate records of the seller

•Certificate of incorporation and all amendments

•Bylaws as amended

•Minute books, including resolutions and minutes of all directors’ and shareholders’ meetings

•Current shareholders list (certified by the corporate secretary), annual reports to shareholders, and stock transfer books

•A list of all states, countries, and other jurisdictions in which the seller transacts business or is qualified to do business

•Applications or other filings in each state listed in (5), for qualification as a foreign corporation and evidence of qualification

•Locations of business offices (including overseas)

B. Agreements among the seller’s shareholders

C. All contracts restricting the sale or transfer of shares of the company, such as buy/sell agreements, subscription agreements, offeree questionnaires, or contractual rights of first refusal; all agreements for the right to purchase shares, such as stock options or warrants; and any pledge agreements by an individual share holder involving the seller’s shares

A. Copies of management and similar reports or memoranda relating to the material aspects of the business operations or products

B. Letters of counsel in response to auditors’ requests for the preceding five years

C. Reports of independent accountants to the board of directors for the preceding five years

D. Revolving credit and term loan agreements, indentures, and other debt instruments, including, without limitation, all documents relating to shareholder loans

E. Correspondence with principal lenders to the seller

F. Personal guarantees of the seller’s indebtedness by its shareholders or other parties

G. Agreements by the seller where it has served as a guarantor for the obligations of third parties

H. Federal, state, and local tax returns and correspondence with federal, state, and local tax officials

I. Federal filings regarding the Subchapter S status of the seller (where applicable)

J. Any private placement memorandum (assuming, of course, that the seller is not a Securities Act of 1934 “reporting company”) prepared and used by the seller (as well as any document used in lieu of a private placement memorandum, such as an investment profile or a business plan)

K. Financial statements of the seller, which should be prepared in accordance with GAAP, for the past five years, including:

•Annual (audited) balance sheets

•Monthly (or other available) balance sheets

•Annual (audited) and monthly (or other available) earnings statements

•Annual (audited) and monthly (or other available) statements of shareholders’ equity and changes in financial position

•Any recently prepared projections for the seller

•Notes and material assumptions for all statements described in K (1) to (5)

L. Any information or documentation relating to tax assessments, deficiency notices, investigations, audits, or settlement proposals

M. An informal schedule of key management compensation (listing information for at least the ten most highly compensated management employees or consultants)

N. Financial aspects of overseas operations (where applicable), including the status of foreign legislation, regulatory restrictions, intellectual property protection, exchange controls, methods for repatriating profits, foreign manufacturing, government controls, import/export licensing and tariffs, and so on

O. Projected budgets, accounts receivable reports (including a detailed aging report, turnover, bad debt experience, and reserves), and related information

A. All employment agreements

B. Agreements relating to consulting, management, financial advisory services, and other professional engagements

C. Copies of all union contracts and collective bargaining agreements

D. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) and any state equivalent compliance files

E. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) files, including safety records and workers’ compensation claims

F. Employee benefit plans (and copies of literature issued to employees describing such plans), including the following:

•Pension and retirement plans, including union pension or retirement plans

•Annual reports for pension plans, if any

•Profit-sharing plans

•Stock option plans, including information concerning all options, stock appreciation rights, and other stock-related benefits granted by the company

•Medical and dental plans

•Insurance plans and policies (including errors and omissions policies and directors’ and officers’ liability insurance policies)

•Any Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP) and trust agreement

•Severance pay plans or programs

•All other benefit or incentive plans or arrangements not covered by the foregoing, including welfare benefit plans

G. All current contract agreements with or pertaining to the seller and to which directors, officers, or shareholders of the seller are parties, and any documents relating to any other transactions between the seller and any director, officer, or shareholders, including receivables from or payables to directors, officers, or shareholders

H. All policy and procedures manuals of the seller concerning personnel; hiring and promotional practices; compliance with the Family Leave Act; drug and alcohol abuse policies; AIDS policies; sexual harassment policies; vacation and holiday policies; expense reimbursement policies; and so on

I. The name, address, phone number, and personnel file of any officer or key employee who has left the seller within the past three years

A. List of all commitments for rented or leased real and personal property, including location and address, description, terms, options, termination and renewal rights, policies regarding ownership of improvements, and annual costs

B. List of all real property owned, including location and address, description of general character, easements, rights of way, encumbrances, zoning restrictions, surveys, mineral rights, title insurance, pending and threatened condemnation, hazardous waste pollution, and so on

C. List of all tangible assets

D. List of all liens on all real properties and material tangible assets

E. Mortgages, deeds, title insurance policies, leases, and other agreements relating to the properties of the seller

F. Real estate tax bills for the real estate of the seller

G. List of patents, patents pending, trademarks, trade names, copyrights, registered and proprietary Internet addresses, franchises, licenses, and all other intangible assets, including registration numbers, expiration dates, employee invention agreements and policies, actual or threatened infringement actions, licensing agreements, and copies of all correspondence relating to this intellectual property

H. Copies of any survey, appraisal, engineering, or other reports relating to the properties of the seller

I. List of assets that may be held on a consignment basis (or that may be the property of a given customer), such as machine dies, molds, and so on

A. Material purchase, supply, and sale agreements currently outstanding or projected to come to fruition within twelve months, including the following:

•List of all contracts relating to the purchase of products, equipment, fixtures, tools, dies, supplies, industrial supplies, or other materials having a price under any such contract in excess of $5,000

•List of all unperformed sales contracts

B. Documents incidental to any planned expansion of the seller’s facilities

C. Consignment agreements

D. Research agreements

E. Franchise, licensing, distribution, and agency agreements

F. Joint-venture agreements

G. Agreements for the payment or receipt of license fees or royalties and royalty-free licenses

H. Documentation relating to all property, liability, and casualty insurance policies owned by the seller, including for each policy a summary description of:

•Coverage

•Policy type and number

•Insurer/carrier and broker

•Premium

•Expiration date

•Deductible

•Any material changes in any of the foregoing since the inception of the seller

•Claims made under such policies

I. Agreements restricting the seller’s right to compete in any business

J. Agreements for the seller’s current purchase of services, including, without limitation, consulting and management

K. Contracts for the purchase, sale, or removal of electricity, gas, water, telephone, sewage, power, or any other utility service

L. List of waste dumps, disposal, treatment, and storage sites

M. Agreements with any railroad, trucking, or other transportation company or courier service

N. Letters of credit

O. Copies of any special benefits under contracts or government programs that might be in jeopardy as a result of the proposed transaction (e.g., small business or minority set-asides, intra-family transactions or favored pricing, internal leases or allocations, and so on)

P. Copies of licenses, permits, and government approvals applied for or issued to the seller that are required in order to operate the businesses of the seller, such as zoning, energy requirements (natural gas, fuel, oil, electricity, and so on), operating permits, or health and safety certificates

Note: This section is critical and will be one key area of the negotiations as discussed in Chapter 11. Therefore, it is suggested that the buyer and its advisory team request copies of all material contracts and obligations of the seller and then organize them as follows:

A. Opinion letter from each lawyer or law firm prosecuting or defending significant litigation to which the seller is a party, describing such litigation

B. List of material litigation or claims for more than $5,000 against the seller asserted or threatened with respect to the quality of the products or services sold to customers, warranty claims, disgruntled employees, product liability, government actions, tort claims, breaches of contract, and so on, including pending or threatened claims

C. List of settlement agreements, releases, decrees, orders, or arbitration awards affecting the seller

D. Description of labor relations history

E. Documentation regarding correspondence or proceedings with federal, state, or local regulatory agencies

Note: Be sure to obtain specific representations and warranties from the seller and its advisors regarding any knowledge pertaining to potential or contingent claims or litigation.

A. Press releases (past two years)

B. Résumés of all key members of the management team

C. Press clippings (past two years)

D. Financial analyst reports, industry surveys, and so on

E. Texts of speeches by the seller’s management team, especially if reprinted and distributed to the industry or the media

F. Schedule of all outside advisors, consultants, and so on, used by the seller over the past five years (domestic and international)

G. Schedule of long-term investments made by the seller

H. Standard forms used (purchase orders, sales orders, service agreements, and so on)

The buyer’s acquisition team and its legal counsel gather data to answer the following ten legal questions during the legal phase of due diligence:

1.What legal steps will need to be taken to effectuate the transaction (e.g., is director and stockholder approval needed, or are there share transfer restrictions or restrictive covenants in loan documentation)? Has the appropriate corporate authority been obtained to proceed with the agreement? What key third-party consents (e.g., FCC, DOJ, lenders, venture capitalists, landlords, or key customers) are required?

2.What antitrust problems, if any, are raised by the transaction? Will filing with the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) be necessary under the premerger notification provisions of the Hart-Scott-Rodino Act?

3.Will the transaction be exempt from registration under applicable federal and state securities laws under the “sale of business” doctrine?

4.What significant legal problems or issues are affecting the seller now or are likely to affect the seller in the foreseeable future? What potential adverse tax consequences to the buyer, the seller, and their respective shareholders may be triggered by the transaction?

5.What are the potential post-closing risks and obligations of the buyer? To what extent should the seller be held liable for such potential liabilities? What steps, if any, can be taken to reduce these potential risks or liabilities? What will it cost to implement these steps?

6.What are the impediments to the assignability of key tangible and intangible assets of the seller company that are desired by the buyer, such as real estate, intellectual property, favorable contracts or leases, human resources, or plant and equipment?

7.What are the obligations and responsibilities of the buyer and the seller under applicable environmental and hazardous waste laws, such as the Comprehensive Environmental Response Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA)?

8.What are the obligations and responsibilities of the buyer and the seller to the creditors of the seller (e.g., bulk transfer laws under Article 6 of the applicable state’s commercial code)?

9.What are the obligations and responsibilities of the buyer and the seller under applicable federal and state labor and employment laws (e.g., will the buyer be subject to successor liability under federal labor laws and as a result be obligated to recognize the presence of organized labor and therefore be obligated to negotiate existing collective bargaining agreements)?

10.To what extent will employment, consulting, confidentiality, or noncompetition agreements need to be created or modified in connection with the proposed transaction?

At the same time, as legal counsel is performing its legal investigation of the seller’s company, the buyer assembles a management team to conduct business and strategic due diligence. The level and extent of this general business and strategic due diligence will vary, depending on the experience of the buyer in the seller’s industry and its familiarity with the target company. For example, a financial buyer who is entering a new industry and has no prior experience with the seller should conduct an exhaustive due diligence—not only on the seller’s company, but also on any relevant trends within the industry that might directly or indirectly affect the deal. In contrast, a management buyout by a group of industry veterans who have been with the seller for an extended period of time will probably require only a minimum amount of business or strategic due diligence; in this case, the focus will be on legal due diligence and the assessment and assumption of risk.

In conducting the due diligence from a business perspective, the buyer’s team is likely to encounter a wide variety of financial problems and risk areas when analyzing the seller. These typically include an undervaluation of inventory, overdue tax liabilities, inadequate management information systems, related-party transactions (especially in small, closely held companies), an unhealthy reliance on a few key customers or suppliers, aging accounts receivable, unrecorded liabilities (e.g., warranty claims, vacation pay, claims, and sales returns and allowances), or an immediate need for significant expenditures as a result of obsolete equipment, inventory, or computer systems. Each of these problems poses different risks and costs for the acquiring company, and these risks must be weighed against the benefits to be gained from the transaction. Note that in view of the significant upheaval in the global economy following the credit crisis and ripple effect events, any type of due diligence will have to include the heightened scrutiny that is demanded by the new order of due diligence best practices.

For the buyer who is just getting to know the seller’s industry, the following two basic questions should be asked:

1.How would you define the market or markets in which the seller operates? What steps will you take to expedite your learning curve for trends within these markets? What third-party advisors are qualified to advise you on key trends affecting this industry?

2.What are the factors that determine success or failure within this industry? How does the seller stack up? What are the image and reputation of the seller within the industry? Does it have a niche? Is the seller’s market share increasing or decreasing? Why? What steps can be taken to enhance or reverse these trends?

The following checklist is designed to provide the acquisition team with a starting point for analysis of the seller. It helps to level the playing field in the negotiations, since the seller usually starts with greater expertise regarding its industry and its business. Here are some examples (this checklist is not intended to be exhaustive) of the topic areas and specific questions that should be addressed in due diligence on a given seller:

1.Has the seller’s organization chart been carefully reviewed? How are management functions and responsibilities delegated and implemented? Are job descriptions and employment manuals, among other similar documents, current and available?

2.What is the general assessment of employee morale at the lower echelons of the corporate ladder? To what extent are these rank-and-file employees critical to the seller’s long-term health?

3.What are the future growth prospects for the principal labor markets that the seller depends on for attracting key employees? Are employees with the necessary skills generally available? How are the seller’s employees recruited, evaluated, trained, and rewarded?

4.What are the background and experience of the seller’s key management team? What is the reputation of this management team within the industry? Has there been high turnover among the seller’s top management? Why or why not? Who are the seller’s key professional advisors and outside consultants?

5.What are the basic management styles, practices, and strategies of the seller’s current team? What are the strengths and weaknesses of the management team? To what extent has the seller’s current management engaged in long-term strategic planning, developed internal controls, or structured management and marketing information systems?

1.What are the seller’s production and distribution methods? To what extent are these methods protected, either by contract or by proprietary rights? Have copies of the seller’s brochures and reports describing the seller and its products and services been obtained?

2.To what extent is the seller operating at its maximum capacity? Why? What are the significant risk factors (e.g., dependence on raw materials or key suppliers or customers) affecting the seller’s production capacity and ability to expand? What are the significant costs of producing the seller’s goods and services? To what extent are the seller’s production and output dependent on economic cycles or seasonal factors? Note: Obtain a breakdown of major sales by specific product and specific customer categories in order to fully assess the seller’s financial performance, dependence on key customers, or product line susceptibility to risk.

3.Are the seller’s plant, equipment, supplies, and machinery in good working order? When will these assets need to be replaced? What are the annual maintenance and service costs for these key assets? At what levels are the seller’s inventories? What are the break-even production efficiency and inventory turnover rates for the target company and how do these compare with industry norms?

4.Does the seller maintain production plans, schedules, and reports? Have copies been obtained and analyzed by the buyer? What are the seller’s manufacturing and production obligations pursuant to long-term contracts or other arrangements? What long-term (post-closing) obligations or commitments for the purchase of raw materials or other supplies or resources have been made?

5.What is the status of the seller’s inventories (e.g., the amount and balance in raw materials and finished goods in relation to production cycles and sales requirements)? What is the condition of the inventory? To what extent is it obsolete?

Note: Be sure to get a breakdown and an analysis of all expenses (e.g., amounts, trends, and categories) in order to assess the profitability of the seller’s business, as well as to determine where post-closing expense savings can be obtained or economies of scale achieved.

1.What are the seller’s primary and secondary markets? What is the size of these markets, and what is the seller’s market share within each market? What strategies are in place to expand this market share? What are the current trends affecting either the growth or the shrinkage of these particular markets? How does the seller segment and reach these markets?

2.Who are the seller’s direct and indirect competitors? What are the respective strengths and weaknesses of each competitor? In what principal ways do companies within the seller’s industry compete (e.g., price, quality, or service)? For each material competitor, the buyer should seek to obtain data on the competitor’s products and services, geographic location, channel of distribution, market share, financial health, pricing policies, and reputation within the industry.

3.Who are the seller’s typical customers? What demographic data have been assembled and analyzed? What are the customers’ purchasing capabilities and patterns? Where are these customers principally located? What political, economic, social, or technological trends or changes are likely to affect the demographic makeup of the seller’s customer base over the next three to five years? What are the key factors that influence the demand for the seller’s goods and services?

4.What are the seller’s primary and secondary distribution channels? What contracts are in place in relation to these channels? How could these channels or contracts be modified or improved? How will these channels overlap or conflict with the buyer’s existing distribution channels?

5.What sales, advertising, public relations, and promotional campaigns and programs are currently in place at the seller’s company? To what extent have these programs been effectively monitored and evaluated?

1.Based on the financial statements and reports collected in connection with the legal due diligence, what key sales, income, and earnings trends have been identified? What effect will the proposed transaction have on these aspects of the seller’s financial performance? What are the various costs incurred in connection with bringing the seller’s products and services to the marketplace? In what ways can these costs be reduced or eliminated?

2.What are the seller’s billing and collection procedures? How current are the seller’s accounts receivables? What steps have been (or can be) taken to expedite the collection procedures and systems? How credible is the seller’s existing accounting and financial control system?

3.What is the seller’s capital structure? What are the seller’s key financial liabilities and debt obligations? How do the seller’s leverage ratios compare to industry norms? What are the seller’s monthly debt-service payments? How strong is the seller’s relationship with creditors, lenders, and investors?

Figure 5-4 discusses a number of potential due diligence problems. A way for the buyer to ensure that the seller has been forthright in disclosing all material obligations and liabilities (whether actual or contingent) is to prepare an affidavit. An affidavit like the one in Figure 5-5 provides additional protection against misrepresentation or material omissions by the seller, its lawyers, and its auditors. The affidavit can be customized to a particular transaction and include the specific concerns that may arise during the transaction and afterward.

Figure 5-4. Common Due Diligence Problems and Exposure Areas

There is a virtually infinite number of potential problems and exposure areas for the buyer that may be uncovered in the review and analysis of the seller’s documents and operations. The specific issues and problems will vary based on the size of the seller, the nature of its business, and the number of years that the seller (or its predecessors) has been in business.

“Clouds” in the title to critical tangible (real estate, equipment, inventory) and intangible (patents, trademarks, and so on) assets. Be sure that the seller has clear title to these assets and that they are conveyed without claims, liens, and encumbrances.

“Clouds” in the title to critical tangible (real estate, equipment, inventory) and intangible (patents, trademarks, and so on) assets. Be sure that the seller has clear title to these assets and that they are conveyed without claims, liens, and encumbrances.

Employee matters. There are a wide variety of employment or labor law issues or liabilities that may be lurking just below the surface but will not be uncovered unless the right questions are asked. Questions designed to uncover wage and hour law violations, discrimination claims, OSHA compliance, or even liability for unfunded persons under the Multiemployer Pension Plan Amendments Act should be developed. If the seller has recently made a substantial workforce reduction (or if you as the buyer are planning post-closing layoffs), then the requirements of the Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification Act (WARN) must have been met. The requirements of WARN include minimum notice of sixty days prior to wide-scale terminations.

Employee matters. There are a wide variety of employment or labor law issues or liabilities that may be lurking just below the surface but will not be uncovered unless the right questions are asked. Questions designed to uncover wage and hour law violations, discrimination claims, OSHA compliance, or even liability for unfunded persons under the Multiemployer Pension Plan Amendments Act should be developed. If the seller has recently made a substantial workforce reduction (or if you as the buyer are planning post-closing layoffs), then the requirements of the Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification Act (WARN) must have been met. The requirements of WARN include minimum notice of sixty days prior to wide-scale terminations.

The possibility of environmental liability under CERCLA or related environmental regulations.

The possibility of environmental liability under CERCLA or related environmental regulations.

Unresolved existing or potential litigation. These cases should be reviewed carefully by counsel.

Unresolved existing or potential litigation. These cases should be reviewed carefully by counsel.

A seller’s attempt to “dress up” the financial statements prior to sale. Often this is an attempt to hide inventory problems, research and development expenditures, excessive overhead and administrative costs, uncollected or uncollectible accounts receivable, unnecessary or inappropriate personal expenses, unrecorded liabilities, tax contingencies, and other such issues.

A seller’s attempt to “dress up” the financial statements prior to sale. Often this is an attempt to hide inventory problems, research and development expenditures, excessive overhead and administrative costs, uncollected or uncollectible accounts receivable, unnecessary or inappropriate personal expenses, unrecorded liabilities, tax contingencies, and other such issues.

Figure 5-5. Affidavit Regarding Liabilities

Prospective Seller, being of lawful age and being first duly sworn upon her oath states:

1. I am the sole shareholder of the S Corporation, which trades under the name “SellerCo,” and I have full right to sell its assets as described in the Bill of Sale dated _______________. Those assets are free and clear of all security interests, liabilities, obligations, and encumbrances of any sort.

2. There are no creditors of SellerCo, or me, or persons known to me who are asserting claims against me or the assets being sold, which in any way affect the transfer to Prospective Buyer of the trade name SellerCo, its goodwill, and its assets, including the equipment as set forth in the Bill of Sale dated _______________. I agree to pay all gross receipt and sales taxes and all employment taxes of any sort due through closing. I am current in regard to these taxes and all other taxes, and there are no pending disputes as to any of my taxes or the taxes of SellerCo.

3. There are no judgments against SellerCo or me in any federal or state court in the United States of America. There are also no replevins, attachments, executions, or other writs or processes issued against SellerCo or me. I have never sought protection under any bankruptcy law nor has any petition in bankruptcy been filed against me. There are no pending administrative or regulatory proceedings, arbitrations, or mediations involving SellerCo or me, and I do not know and have no reasonable ground to know of any proposed ones or any basis for any such actions.

4. There are no known outstanding claims by any employees of SellerCo or me, and I expressly recognize that no claims of, by, or on behalf of any employees arising prior to closing are being transferred to Prospective Buyer.

5. There are no and have been no unions that have been or are involved in any business that I own, and particularly, SellerCo. Furthermore, there currently is no union organizational activity under way in any business that I own, and particularly, SellerCo.

6. There are and have been no multi-employer pension plans or other pension or profit-sharing plans involved in any business that I own, and particularly, SellerCo.

7. I have always conducted SellerCo according to applicable laws and regulations.

8. From the time when the purchase agreement was executed through closing, I have conducted the business called SellerCo only in the usual and customary manner. I have entered into no new contracts and have assumed no new obligations during that time period.

9. I shall remain fully liable for payment of all bills, accounts payable, or other claims against SellerCo or me created prior to closing. None of them are being transferred to Prospective Buyer.

10. I hereby warrant and represent to Prospective Buyer that all statements in paragraphs one through nine of this Affidavit are true and correct.

11a. I agree to indemnify and hold harmless Prospective Buyer in respect to any and all claims, losses, damages, liabilities, and expenses, including, without limitation, settlement costs and any legal, accounting, and other expenses for investigating or defending any actions or threatened actions, reasonably incurred by Prospective Buyer in connection with:

i.Any claims or liabilities made against Prospective Buyer because of any act or failure to act of myself arising prior to closing in regard to SellerCo; or

ii.Any breach of warranty or misrepresentation involved in my sale of SellerCo to Prospective Buyer.

11b. As to claims or liabilities against Prospective Buyer arising prior to closing in connection with SellerCo, or any claim arising at any time in regard to any profit-sharing or pension plan started prior to closing involving SellerCo, or any breach of warranty or other material misrepresentation made by me, I agree that Prospective Buyer has the option to pay the claim or liability and deduct the amount of it from any money owed to me, after giving me reasonable notice of the claim and reasonable opportunity to resolve it. This right of setoff expressly applies to any damages Prospective Buyer suffers as a result of any breach of any warranty I have given to Prospective Buyer. Prospective Buyer’s right of setoff against any money owed me shall not be deemed his exclusive remedy for any breach by me of any representations, warranties, or agreements involved in the sale of SellerCo to him, all of which shall survive the closing and any setoff made by Prospective Buyer.

12. I agree to execute any further documents to complete this sale.

Prospective Seller

Subscribed and Sworn to before me this _______day of

____________, 20____.

Notary Public

My Commission Expires: ____________

Note: Proper use of this affidavit depends on the exact type of purchase agreement used.

Figure 5-6. The Emergence of Virtual Data Rooms

It appears that the age of bad hotel rooms, expensive travel costs, and bad donuts in classic due diligence data rooms is slowly but surely being replaced with “virtual data rooms,” or VDRs. Virtual data rooms use existing computer software and Internet technology to provide a secure online format for reviewing and organizing due diligence information. The documents are easier to search and index when they are already online, and the use of a VDR prevents “water cooler rumor mills” about what the guys in suits are doing in the corner conference room. The VDR does require the company’s IT department to be involved early and often in the overall selling process. The VDR also better facilitates the review of certain types of data that are easier to review online and in electronic form, such as CAD drawings, video files, patent filings, and architectural drawings. Are VDRs growing in acceptance? It appears so. IntraLinks (www.intralinks.com), a leading provider of VDR software and systems, handled 50 transactions in 2001, 450 in 2004, and predicts being a technology provider to 1,500 transactions in 2005. In January of 2009, it was reported that IntraLinks had facilitated 55,000 projects and transactions and had had six consecutive years of double-digit growth. By 2016, virtual data rooms had hosted hundreds of thousands of transactions and Intralinks alone was used by 3.1 million professionals on transactions valued at over $13 trillion dollars.

Significant portions of the due diligence process have shifted online, as shown in Figure 5-6; however, these technology tools should be used as an asset and not a crutch. There is still no substitute for problem-specific due diligence being done on a face-to-face basis, where interactivity, follow-on questions, body language, and voice inflection can be very enlightening and revealing.

Due diligence must be a cooperative and patient process involving both the buyer’s and the seller’s teams. Any attempts to hide or manipulate key data will only lead to problems down the road. Material misrepresentations or omissions can (and often do) lead to post-closing litigation, which is expensive and time-consuming for both parties. Another mistake in due diligence that sellers often make is to forget the human element. I have worked on deals where the lawyers were sent into a dark room in the corner of the building, without any support or even coffee; on other deals, we were treated like royalty, with full access to support staff, computers, telephones, food, and beverages. It is only human for the buyer’s counsel to be a bit more cooperative in the negotiations when the seller’s team is supportive and allows counsel to do his job.

Post-Sarbanes-Oxley

Due Diligence Checklist

In the 1990s, acquirers rarely had the opportunity to conduct extensive, time-consuming due diligence. Buyers were seldom granted exclusivity periods, and the typical auction might have allowed the potential buyer only a day or two in the data room (which sometimes had a no-copy rule) and a few hours of management interviews. After the Enron scandal and a few others hit the American corporate world, the Public Company Accounting Reform and Investor Protection Act of 2002, also known as the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (Sarbox), was enacted, which changed the way in which businesses were conducted and corporate governance was practiced. Sarbox lays out a government-mandated disclosure process that is monitored by auditors, certified by top-level executives under penalty of prison, and reviewed by the SEC. It addresses corporate responsibility, the creation of a public-company accounting oversight board, auditor independence, and enhanced criminal sanctions. The effect of Sarbox has been to compel investment banks, regulators, shareholder groups, plaintiffs’ lawyers, and other parties to analyze companies with a focus on the broad mandates of Sarbox.

Sarbox does not apply only to large publicly traded corporations; privately held companies can also be subject to Sarbox. Lenders and customers can each require a company to adopt Sarbox-style procedures. A company’s accountants and its directors’ and officers’ (D&O) insurance carrier can also prompt a company to do so.

Potential acquirers must be aware of the main federal corporate disclosure requirements: Regulation S-K, SFAS No. 5, and Sarbox.

Regulation S-K, issued by the SEC, acts as an instruction manual for public companies filing their annual, quarterly, and interim reports. The important provisions are as follows:

1.Item 101 requires reporting companies to describe their businesses, products, and competition as well as report on their financial position by industry segments. Companies must discuss transactions outside of the ordinary course of business, R&D activities, intellectual property, backlog, foreign operations, and the anticipated costs and effects of environmental compliance—both current and projected.

2.Item 103 calls for companies to disclose any large non-routine legal proceedings to which they are a party, and even some routine matters that exceed certain thresholds. Also, Item 103 requires a company’s management to discuss known trends, events, and uncertainties that could have a material effect on its business.

3.Item 402 calls for a detailed review of the company’s executive compensation, employee contracts, benefits, options, and so on.

4.Item 404 focuses on related-party transactions. Material contracts are to be included as exhibits to the periodic filings, so many times credit agreements, joint venture agreements, and even real estate leases are on the public record.

Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 5, Accounting for Contingencies, issued by the Financial Accounting Standards Board, deals with disclosing loss contingencies. Observing SFAS No. 5 is part of complying with generally accepted accounting principles and is a key element in the audit letter process. It requires a company to establish a loss contingency in its financial statements if:

1.Available information indicates that it is probable that the company has suffered a loss.

2.The amount of that loss can be reasonably estimated.

Sarbox introduces stringent disclosure requirements for companies. The main disclosure requirements that a potential acquirer must keep in mind are as follows:

1. Section 302 of Sarbox requires the chief executive officer and the chief financial officer of a company to personally certify certain items about the annual or quarterly report being filed. In summary, they must certify that:

They have read the report.

They have read the report.

The report fairly presents the company’s financial condition and results of operations.

The report fairly presents the company’s financial condition and results of operations.

To their knowledge, the report contains no untrue statements or omissions of material fact that would make the statements misleading.

To their knowledge, the report contains no untrue statements or omissions of material fact that would make the statements misleading.

They are responsible for and have evaluated the company’s disclosure controls and procedures, and its internal controls over financial reporting.

They are responsible for and have evaluated the company’s disclosure controls and procedures, and its internal controls over financial reporting.

2. Under Section 906 of Sarbox, senior officers can be subject to potential criminal liability if they falsely, knowingly, or willfully make an inaccurate Section 302 certification. These provisions together obligate the buyer’s CEO and CFO to certify the financial statements and internal disclosure controls of the combined company as of the end of the first quarter post-acquisition. In major acquisitions, this can be an impossible task if substantial due diligence was not done prior to the closing.

3. Under Section 404, a company has to establish and maintain adequate internal control structures and processes to allow for accurate financial reporting. In the company’s annual report, senior executives need to assess and report on the effectiveness of these internal control structures and processes. Furthermore, the company’s auditors must provide an independent report on management’s assessment.

Taken together, these measures require reporting companies (and companies otherwise observing these requirements) to:

Review their liability assessment and reporting practices and, if necessary, adopt new ones.

Review their liability assessment and reporting practices and, if necessary, adopt new ones.

Regularly obtain and evaluate insurance company risk assessments for the company’s properties.

Regularly obtain and evaluate insurance company risk assessments for the company’s properties.

Include environmental matters in their Item 303 Management Discussion and Analysis.

Include environmental matters in their Item 303 Management Discussion and Analysis.

Discuss pending and threatened litigation and regulatory enforcement actions in their periodic reports.

Discuss pending and threatened litigation and regulatory enforcement actions in their periodic reports.

Disclose and value contingent liabilities in their financial statements, including those related to legal, operational, warranty, and environmental issues.

Disclose and value contingent liabilities in their financial statements, including those related to legal, operational, warranty, and environmental issues.

Implement and periodically evaluate Section 404 internal controls and procedures.

Implement and periodically evaluate Section 404 internal controls and procedures.

Perform the actions called for by their internal controls and procedures, including maintaining internal records, establishing milestones for regularly evaluating known problem areas, searching out new problem areas, and providing reports up and down the management chain.

Perform the actions called for by their internal controls and procedures, including maintaining internal records, establishing milestones for regularly evaluating known problem areas, searching out new problem areas, and providing reports up and down the management chain.

Have all of the above reviewed, evaluated, and certified by senior management.

Have all of the above reviewed, evaluated, and certified by senior management.

Have all of the above formally reviewed and audited by their accountants.

Have all of the above formally reviewed and audited by their accountants.

Among other things, audit committees must enact whistle-blowing procedures to report questionable accounting or auditing practices. The buyer should also compare the target’s internal controls with its own to identify any deficiencies or differences. This will enable the buyer to prepare integration steps to harmonize both sets of control procedures after closing.

In particular, acquiring companies need to:

Expand their review of publicly available information to include the EPA Enforcement and Compliance History (ECHO) list and periodic reports filed by the target with the SEC.

Expand their review of publicly available information to include the EPA Enforcement and Compliance History (ECHO) list and periodic reports filed by the target with the SEC.

Specifically inquire about their target’s internal review processes and procedures.

Specifically inquire about their target’s internal review processes and procedures.

Review the target’s internal operational, real estate, intellectual property, insurance, litigation, and environmental policies.

Review the target’s internal operational, real estate, intellectual property, insurance, litigation, and environmental policies.

Examine the internal committees charged with monitoring and assessing the target’s Sarbox compliance, including getting a list of committee members and their functions.

Examine the internal committees charged with monitoring and assessing the target’s Sarbox compliance, including getting a list of committee members and their functions.

Consider whether other internal procedures might touch on managerial, financial, and operational issues (for example, as part of the target’s accounting and legal functions).

Consider whether other internal procedures might touch on managerial, financial, and operational issues (for example, as part of the target’s accounting and legal functions).

Inquire about what is generally known as the disclosure controls committee, a general oversight committee that may gather and evaluate information generated by the internal review structure.

Inquire about what is generally known as the disclosure controls committee, a general oversight committee that may gather and evaluate information generated by the internal review structure.

Obtain all minutes, reports, memoranda, and valuations generated by these internal procedures.

Obtain all minutes, reports, memoranda, and valuations generated by these internal procedures.

Review the work papers and reports generated by the target’s auditors while assessing the company’s internal controls.