Boards of directors are playing an increasing and critical role in M&A transactions in 2017 and beyond. Boards must embrace key principles of due diligence, buy vs. build analysis, financial analysis, and risk assessment as primary factors in their decision-making and evaluation process, both for M&A as well as other capital investment proposals. Transactions should help drive shareholder value and be aligned with both short-term and long-term strategic objectives. They should be accretive not dilutive to the market price of the company’s shares as well as to the company’s brand, reputation, and to consumer perception of its core products and services. Transactions must be structured and implemented in a manner where they will be able to withstand second-guessing and searching by an increasing pool of shareholder activists and by courts who seem increasingly more willing to play “Monday morning quarterback” in their analysis of transactions. Screens and filters need to be in place to ensure that risk is avoided and strategic objectives are met. Analysis must be conducted to predict and mitigate any post-closing litigation risk or costly post-closing integration challenges. The new corporate governance paradigm and state of the law is that boards can and will be held accountable and responsible for misguided strategies and/or transactions that are not carefully assessed and evaluated.

Boards and company leaders must embrace and understand the notion that there is no more complicated transaction than a merger or acquisition. The issues raised are broad and complex, from valuation and deal structure to tax and securities laws. It seems that virtually every board member executive in every major industry faces a buy-or-sell decision at some point during her tenure as leader of the company. In fact, it is estimated that some executives spend as much as one-third of their time considering merger-and-acquisition opportunities and other structural business decisions. The strategic reasons for considering such transactions are also numerous, from achieving economies of scale to mitigating cash-flow risk via diversification to satisfying shareholder hunger for steady growth and dividends. The federal government’s degree of intervention in M&A transactions varies from administration to administration, depending on the issues and concerns of the day.

Recent years have witnessed a significant increase in merger-and-acquisition activity within a wide variety of industries that are growing rapidly and evolving overall, such as health care, information technology, education, and software development, as well as in traditional industries such as manufacturing, infrastructure, consumer products, and food services. Many developments reflect an increase in strategic buyers and a decrease in the amount of leverage, implying that these deals were being done because they made sense for both parties. That was far from the case with the highly leveraged, financially driven deals of the late 1980s.

Boards of companies in small-to middle-market segments need to understand the key drivers of valuation since they are often able to focus their operating goals to maximize the potential valuation range. Therefore, it is important to know that the valuation of the target company directly correlates with the following characteristics:

1.Strong revenue growth

2.Significant market share or strong niche positions

3.A market with barriers to entry by competitors

4.A strong management team

5.Strong, stable cash flow

6.No significant concentration in customers, products, suppliers, or geographic markets

7.Low risk of technological obsolescence or product substitution

Successful mergers and acquisitions are neither an art nor a science but a process. In fact, regression analysis demonstrates that the number-one determinant of deal multiples is the growth rate of the business. The higher the growth rate, the higher the multiple of cash flow the business is worth.

For example, boards on both the buy-side and sell-side of the transaction need to understand that when a deal is improperly valued one side wins big while the other loses big. By definition, a transaction is a failure if it does not create value for shareholders. The easiest way to fail, therefore, is to pay too high a price. To be successful, a transaction must be fair and balanced, reflecting the economic needs of both buyer and seller, and must convey real and durable value to the shareholders of both companies. Achieving this involves a review and analysis of financial statements, a genuine understanding of how the proposed transaction meets the economic objectives of each party, and recognizes the tax, accounting, and legal implications of the deal.

A transaction as complex as a merger or acquisition is fraught with potential problems and pitfalls on both sides of the table. Many of these problems arise either in the preliminary stages, such as when the parties force a deal that shouldn’t really be done (i.e., some couples were just never meant to be married). Other times, inadequate, rushed, or misleading due diligence results in mistakes, errors, or omissions; risks are not properly allocated during the negotiation of definitive documents; or it becomes a nightmare to integrate the companies after closing. These pitfalls can lead to expensive and protracted litigation unless an alternative method of dispute resolution is negotiated and included in the definitive documents.

The board can and should play a key role in overseeing the M&A deal team and C-level executives in making sure that valuations are accurate and being assessed properly, that due diligence is complete, and that the integration that follows a deal does not undermine the company’s very reason for doing the deal to begin with. When boards fail to play an active role in the deal process, a company can wind up entering into a transaction that it later regrets. Classic mistakes include a lack of adequate planning, an overly aggressive timetable to closing, a failure to really look at possible post-closing integration problems, or, worst of all, that projected synergies turn out to be illusory. By engaging in the M&A process early and often, developing a strategy and process, and carefully overseeing the role of the executive team, a board can make sure that a company does not make any of these classic mistakes.

Generally, proposing, planning, and implementing M&A transactions are the responsibility of a company’s executive team. With the board’s oversight, it is the executive team that will develop the acquisition plan that leads to M&A transactions. But that does not mean that the board won’t play an integral role in the M&A process; the board must act in a way that is consistent with its fiduciary duties as caretakers and gatekeepers of the company’s tangible and intangible assets. An engaged board will develop the company’s overall strategic direction and might determine that growth should be driven through acquisition. In the alternative, it might determine that the best way for a company to maximize value to shareholders is to sell itself or certain of its key assets. The board must understand that its decision-making process, the depth and breadth of the information it considered to make its decision, and the reasonableness of the board’s actions will all be under the microscope as viewed by shareholders, stakeholders, regulations, activists, and possibly even the courts.

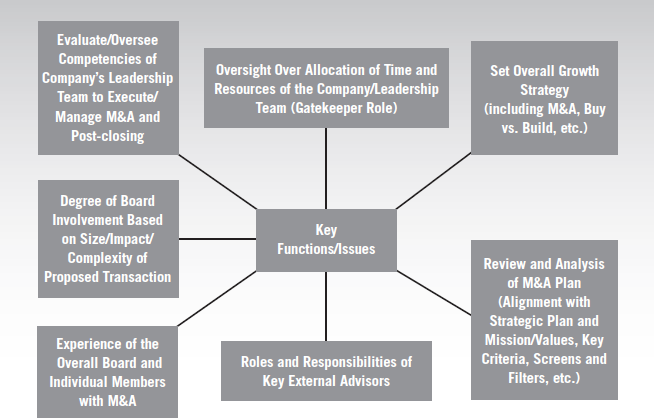

It is in this environment that the company’s executive team will develop a specific acquisition strategy, which might lead to the identification of M&A targets, perhaps with the help with an investment bank or other advisors. The board will also identify and assess key risks, supervise and test the premises of a proposed transaction, and insure that the M&A transaction being proposed by the company’s executive team will be in the best interests of the company and ultimately drive shareholder value. If the company wishes to sell, the board will give its input into that approach as well as evaluate various offers and determine whether a deal being offered is fair and maximizes value for shareholders. See Figure 6-1.

The board’s role in the context of M&A can be broken into its macro roles and micro roles. In the macro, the board should:

Embrace and meet its various fiduciary obligations. This will be addressed further in the next section.

Embrace and meet its various fiduciary obligations. This will be addressed further in the next section.

Oversee the company’s management as it negotiates the contours of a particular deal.

Oversee the company’s management as it negotiates the contours of a particular deal.

Test and confirm the economic premise of the proposed transaction—namely, perform its own analysis of the management’s justification for doing the deal to see if it reaches the same conclusion.

Test and confirm the economic premise of the proposed transaction—namely, perform its own analysis of the management’s justification for doing the deal to see if it reaches the same conclusion.

Confirm the value proposition that the deal offers to the company’s shareholders.

Confirm the value proposition that the deal offers to the company’s shareholders.

Confirm that management has taken necessary steps to mitigate the risk of the transaction and reduce the chances of conflict and litigation later on.

Confirm that management has taken necessary steps to mitigate the risk of the transaction and reduce the chances of conflict and litigation later on.

Assist management in addressing the fear, uncertainties, and doubts of employees and company teams.

Assist management in addressing the fear, uncertainties, and doubts of employees and company teams.

Confirm that management is planning the post-closing integration adequately.

Confirm that management is planning the post-closing integration adequately.

In the micro, the board should:

Confirm compliance regarding timing and scope of disclosure of the transaction to various constituencies particularly with an eye toward prevention of any insider trading.

Confirm compliance regarding timing and scope of disclosure of the transaction to various constituencies particularly with an eye toward prevention of any insider trading.

Consult with the executive team regarding the due diligence process to make sure that all necessary steps have been taken to mitigate post-closing risk.

Consult with the executive team regarding the due diligence process to make sure that all necessary steps have been taken to mitigate post-closing risk.

Confirm that the company has obtained key third-party approvals, whether regulatory or contractual. In some instances, the board may actually assist the company in this respect.

Confirm that the company has obtained key third-party approvals, whether regulatory or contractual. In some instances, the board may actually assist the company in this respect.

Review the allocation of purchase price to confirm that allocation of the risks and rewards of the transaction is fair and reasonable relative to upside.

Review the allocation of purchase price to confirm that allocation of the risks and rewards of the transaction is fair and reasonable relative to upside.

The board’s responsibilities with respect to M&A go well beyond providing strategic advice and oversight. The board’s obligation to drive shareholder value results from its fiduciary duties to the company. Fiduciary duties are legal obligations, which fall into two broad general categories: the duty of care and the duty of loyalty. When directors violate these duties, courts may impose monetary liability upon them or may invalidate or enjoin their actions. The key starting point for understanding the nature and scope of these duties and how they dictate the board’s role in M&A is considering what actions and decisions a court will not disturb.

Under the business judgment rule, directors are presumed to have made a business decision on an informed basis, in good faith, and in honest belief that their actions were taken in the best interest of the company. And when they do in fact act in this manner, directors will not have their decisions second-guessed by a court, even if the decision turns out to be a bad one. That is, directors’ fiduciary duties do not bar them from taking business risks, and courts generally are not in the business of substituting their business judgment for that of directors, or otherwise engaging in substantive evaluations of business decisions or outcomes.

So, when will a court disturb a business decision made by a board of directors or impose liability on such decision makers? When the directors act in a manner contrary to the presumptions of the business judgment rule—that is, when they fail to act on an informed basis, in good faith, or in honest belief that their actions are in the best interest of the company. These are issues that judges and lawyers are in a position to scrutinize; business expertise is not necessary. The focus of the judicial review, therefore, is on the process undertaken by the board, particularly whether that decision-making process was materially flawed or inadequate, or whether it was tainted or driven by personal interests instead of by the company’s interests. These concepts are embodied in the directors’ duties of care and loyalty.

When making a decision, directors must actively gather material information regarding the company’s affairs and then act upon that information with the diligence, care, and skill necessary to make a rational business decision. Board members are entitled to rely primarily on the data provided by officers and professional advisors, provided that they have no knowledge of any irregularity or inaccuracy in the information. But they cannot act in a grossly negligent manner. That is, they risk breaching their duty of care when they remain willfully ignorant of material information or, even when in possession of such information, rush a decision so they cannot reasonably and responsibly evaluate the options. I’ve even seen cases in which board members were held personally responsible for misinformed decisions if their duty of care was not taken seriously.

In the context of selling the company, the duty of care means that the board must “undertake reasonable efforts to secure the highest price realistically achievable given the market for the company.”1 This standard is actually tougher than the one courts employ when applying the business judgment rule to ordinary board decisions, which as noted above only requires that the board act in an informed manner, in good faith, and with the assumption that its actions are in the best interests of the company. Because in the context of M&A the board has “Revlon duties,” when looking at a board’s actions in a sale, the court will take a substantive look at what a board did to get the highest reasonable price.

Because the board has these Revlon duties, it should develop a process whereby it will maximize shareholder value, which drills down into fair pricing, fair dealing, and a strong plan for post-closing integration and value maximization. While not a requirement under Revlon, the board may engage in an auction process to fetch the highest price for the company. It also might mean that once the company receives an offer, the board should actively seek additional offers to make sure that the company is getting the best deal possible. In any event, the board should be well educated on various devices it can employ to make sure the company is getting the best deal. Furthermore, the board should carefully document its role in the M&A process and the various steps it took to maximize the sale price so that it can demonstrate that it undertook such reasonable efforts.

Consider how the Delaware Chancery Court viewed the possible sale of Netsmart Technologies, Inc. Its decision in In re Netsmart Technologies, Inc., Shareholders Lit. criticized Netsmart’s board’s decision to only consider private equity firms as potential buyers to the exclusion of strategic buyers. The court also criticized the board’s failure to keep minutes of an important meeting where this decision was made. This emphasizes the point that process and recordkeeping are important if a board is not going to breach its fiduciary duties during the M&A process.

Recent Delaware cases have established that, in a limited set of circumstances, the business judgment standard may apply in the context of M&A. In In re MFW Shareholders Litigation (Del. Ch. May 29, 2013, referred to as MFW), the Delaware Chancery Court held that the board satisfies its duty when reviewing a going-private transaction with a controlling stockholder if the merger receives the approval of either (i) a special committee of directors independent of the controlling stockholder that is fully empowered to decline the transaction and such committee relies on its own advisors and satisfies the duty of care in negotiating the sale price or (ii) a majority of the stockholders not affiliated with the majority stockholder, provided that such stockholders are uncoerced in their vote and fully informed.

Another recent Delaware Chancery Court case, In re Volcano Corporation Stockholder Litigation, demonstrates that the MFW logic can apply to other situations as well. In Volcano, the court determined that the tendering of shares by a majority of fully informed, uncoerced, disinterested stockholders essentially has the same effect as a majority vote of unaffiliated stockholders, effectively cleansing the transaction in question and causing the transaction to be subject to review in accordance with the business judgment.

Each director must exercise his or her powers in the interest of the corporation and not in his or her own interest or that of another person or organization. The duty of loyalty has a number of specific applications: The director must avoid any conflicts of interest in dealings with the corporation and cannot extract personal benefits from the corporation that are not shared by all of the shareholders. The director must not personally usurp what is more appropriately an opportunity or business transaction to be offered to the corporation. For example, say an officer or director of the company was in a meeting on the company’s behalf and a great opportunity to obtain the distribution rights for an exciting new technology was offered. It would be a breach of this duty to try to obtain those rights for himself and not first offer them to the corporation. Further, the director cannot act in bad faith and for a purpose other than advancing the best interests of the corporation. For example, the director cannot knowingly cause the corporation to violate the law, cannot consciously disregard his obligation to oversee the corporation’s activities and thereby sanction misconduct by the corporation and its employees, and cannot waste corporate assets.

The board’s duty of loyalty impacts its role in M&A in numerous ways. Essentially it means that a board member’s decisions can only be driven by a desire to maximize shareholder value. A director would be violating this duty of loyalty if she supported a deal that benefited a company in which she had a stake solely because the deal would benefit her directly or indirectly. It would also be a breach of the duty of loyalty if she determined that one buyer of the company was better than another because that buyer promised her a bigger role after the sale. In short, directors cannot put their own interests before the company’s.

To the extent that “interested” directors play too large of a role on a board, the board risks losing the presumption of the business judgment rule, meaning that courts will scrutinize the decisions made by a board deemed not to be impartial with respect to a particular matter. To that end, in the context of considering M&A transactions (or other situations in which one or more directors could be deemed to have misaligned interests), interested directors should consider recusing themselves from discussing and voting on relevant transactions. The board could also form a special committee comprised of only outside directors to control the sale process in order to avoid any potential conflicts of interest.

Several recent Delaware cases have highlighted how the duty of loyalty impacts financial advisors in M&A transactions. The recent Del Monte, El Paso, and Rural Metro decisions in the Delaware Chancery Court have shown that courts are also concerned about disloyal financial advisors. But these cases implicate boards as well. Under this recent case law, boards have a responsibility to oversee financial advisors and be on the lookout for potential conflicts of interests (e.g., a bank favoring buyers who will seek financing from that bank). In other words, the board must adhere to its Revlon duties throughout the sale process, not just at the approval stage, and the disloyalty of a financial advisor can lead to board liability.

Boards need to always take their fiduciary duties very seriously, but this is particularly true in the context of M&A and related transactions, especially those that may be cross-border in nature. In order to do so, a diligent board may wish to hire independent counsel to advise it of its duties in the context of the particular situation the company is in. Boards should remain diligent in their oversight role and always play the role of “constructive skeptic” when political transactions and their alleged value propositions are presented for debate and appeal.

In conclusion, boards on both sides of any transaction will have the best chance to avoid bad deals with bad consequences—and the litigation that often follows them—if they remain steadfast in their focus on core principles of stewardship and on their key fiduciary duties, develop and encourage a sound M&A process, and are diligent about keeping records of their decisions and actions.

1. In re Netsmart Technologies, Inc. Shareholder Litigation, 2007 WL 1576151 (Del. Ch.)