#25 HOW MUCH SHOULD I EAT?

Portion sizes have increased so dramatically over the past few decades that most of us haven’t got a clue about how much we should eat for breakfast, lunch or dinner. This ‘portion distortion’ appears to have started with the fast-food industry – these businesses realised that they could increase the size of a meal at very little cost, charge more for it and still appear to be offering a bargain. It reached its climax with the ‘super-size me’ phenomenon, which was eventually halted in 2004 after negative public reaction to the documentary film Super Size Me.

However, you still have the option to buy large portions, and they still appear to be much better value than the smaller portions. A small fries from McDonald’s is 231 calories, and a large fries is 405 – but the price difference doesn’t reflect this so it could almost be regarded as sensible to choose the larger option. A small cola drink is 230 ml, the large is 500 – more than double the calories unless it’s a sugar-free option. There’s nothing special about McDonald’s, either – these sorts of practices occur everywhere, and not just in the big-brand fast-food chains. Here are some other examples of oversized foods:

# Muffins – at one time, these were cupcakes or fairy cakes. They were pretty small, and maybe took four or five delicate bites to eat. Now, they are massive. A double chocolate muffin from Muffin Break comes in at 166 g and delivers 633 calories (plus 5.1 g of fibre – so there’s some good news).

# Scones – in the past, scones were something your mother or grandmother whipped up when visitors turned up, and they typically measured 5–6 cm in diameter. Now, go into a café and it’s not uncommon to see scones that are 15 cm in diameter.

# Toasted sandwiches – these used to consist of two slices of bread with a bit of cheese and something else (tomato/pineapple/onion – pick your pleasure). Now, lots of places serve a toasted sandwich that consists of three slices of bread, each glued to the other with filling.

# Chocolate bars – not content with offering us portable, affordable treats, chocolate companies have provided us with several ways to eat more of these goodies. First we had the ‘king-sized’ bar, then we had the ‘twin-pack’ – the idea being that we’d share this (yeah, right). We can also buy a share-pack of mini-sized treats. Although this might not be seen as oversizing, it encourages over-consumption because each little treat is so more-ish that once you start, it’s hard to stop. And there’s a whole bag of them.

# Potato chips – while you can still buy small individual packs, larger sizes dominate the supermarket shelves. Those large packs are meant to be shared – but it’s pretty easy for one person to eat most of a pack. Sizes have increased, too: a single pack of this type of snack food used to be 30 g; now it’s often 40 g. Years ago, a party-size offering was three 100 g packs in a cardboard box – now we’re regularly given the chance to buy three 150 g packs for $4, which makes a single 40 g pack look like a waste of money.

# Fizzy drinks – the size increase here is similar to that for potato chips: small sizes are still available, but large sizes dominate the market. As a result, we’re conditioned to buying much larger quantities. Sadly, it’s all too common to see children and younger adults walking around with 1.25-litre bottles of fizzy drink.

And it’s not just fast foods that have grown in size. In the 1980s, a typical dinner plate in the US was 25 cm in diameter; by the 2000s it was 30 cm, providing an extra 44% of plate that could be filled with food. This has also happened in Australia, New Zealand, the UK and probably many other countries, too. What used to be regarded as a dinner plate is now called a side plate. There is some evidence that larger plate sizes encourage larger portion sizes. This would be fine if the extra space on the plate was taken up with low-calorie, nutrient-dense vegetables – but too often it’s filled up with rice, potatoes or pasta.

MAKE-UP OF A MEAL

What does a good meal look like? Ideally, it will contain a mix of lean protein, colourful vegetables, something that delivers healthy fats, and some carbohydrate if needed. Now the question is how much of each of these types of food you should eat.

Traditional approaches to portion control tend to focus on calorie counting. ‘You need X calories of protein, Y calories of fat, Z calories of carbohydrate.’ It’s good to have a general idea of the energy density of your food, but counting calories is a bit soul-destroying and for most people it takes away from the pleasure of eating.

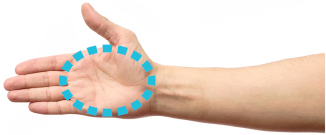

An alternative approach is to use volume. You could measure out a cup of this and a half-cup of that – but there’s an easier way, and that’s to use the size of your hands as a guide. The advantage here is that the size of your hands is in proportion to the size of your body – this means that if you’re 2 metres tall, you’ll have a bit more food on your plate than if you’re only 1.6 metres, which makes up for the extra energy you need to run a bigger body.

The other advantage of using your hands as a guide is that they are always with you. Eating out? Use your hands as a guide to how much you should be eating – regardless of the size of meal served up.

HANDS GUIDELINE

For each meal:

# Lean protein – one palm-sized portion for red meat or chicken; one flat hand for white fish.

# Non-starchy vegetables – two cupped handfuls, or more if you like.

# Carb-dense foods – one cupped handful.

# Fat-dense foods – one thumb-sized portion.

1 PALM OF RED MEAT OR CHICKEN

2 CUPPED HANDFULS OF NON-STARCHY VEGE

1 CUPPED HANDFUL OF CARBS

1 THUMB OF FAT

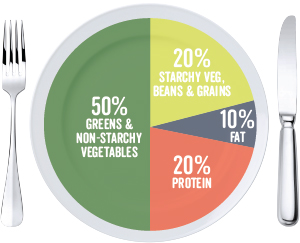

DESIGN YOUR PLATE

The other way is to design your plate so that about half of it contains non-starchy vegetables, about a fifth of it is whole grains, starchy vegetables or beans, a fifth is protein and just a tenth of the plate contains some healthy fats, like avocado or oily fish. This is a very easy, practical way to look at a meal, and can be applied to virtually any situation.

ADAPT AS NEEDED

Now, these examples are general guidelines only. Adapt them to your particular situation. Here are some examples:

# You’re feeling really hungry: First, add extra non-starchy vegetables – you can easily double the amount on your plate. If you still need more, opt for extra protein before adding extra carbs.

# You’re trying to lose weight: Leave the carbs off the plate, and add extra vegetables. If you really want to have some carbs, trying halving the amount on your plate.

# You’re trying to gain weight: Increase the amount of everything on your plate.

# You’re trying to gain muscle: Increase the amount of protein and non-starchy vegetables on your plate.

# You’ve had a carb-heavy breakfast: Leave carbs out of your lunch and dinner, or at least reduce the quantity. Add extra vegetables to make up the volume.

# You’ve had a very physically active day: Increase the amount of everything on your plate.

# You’re going out for dinner tonight: Don’t eat any carbs at breakfast or lunch. Stick to the nutrient-dense protein and veges, with a bit of good fat.

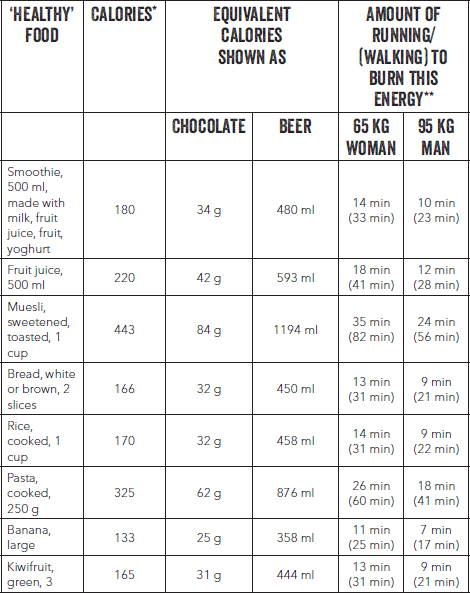

IT COSTS HOW MUCH?!

Often, we don’t realise exactly how much energy is stored in foods that we eat every day. Some foods have a ‘health halo’ – we think they are good for us, but in fact they may be hurting our efforts to stay lean. The examples on the following page turn ‘healthy’ foods into their ‘unhealthy’ equivalents, and also show just how much exercise is needed to burn off that energy.

* Will vary depending on ingredients. Equivalents are based on 100 g chocolate being 530 calories and 1 litre of beer being 371 calories.

** Assumes a running pace of 12 km per hour, or a very brisk walking pace of 6.5 km per hour; times in minutes (min) are rounded to the nearest minute.

THE FRUIT FACTOR

Fruit is generally regarded as being good for us – and it’s certainly a lot better than processed foods like bars and biscuits. But just because something is good for you doesn’t mean that you should eat vast, unlimited amounts of it. Whichever way you look at it, that’s not part of a healthy, balanced diet.

Fruit does contain fibre and phytonutrients, but it also contains sugar. True, that sugar isn’t absorbed into your body as quickly as the sugar you put in your tea, but it still delivers calories. So, if you’re looking to manage your weight, then it’s worth being aware that eating too much fruit could hurt your chances of success.

One or two pieces of fruit a day are fine – but if you find yourself snacking on 10 kiwifruit each day, then you’ll be eating a massive 550 calories, which is a big chunk of your daily needs. Bananas – our favourite fruit – are around 150 calories each, which is about the same as two chocolate digestives or Afghan biscuits. If you’re aware that this is part of your energy intake and you adjust the rest of your diet to compensate, then maybe it will be OK. But most of us view fruit as ‘free food’, to be consumed without any consequences.

Try to keep fruit intake to two portions a day, and choose fruits that are highly coloured (blueberries, raspberries, oranges, plums, peaches) so that you get a good dose of phytonutrients at the same time.

A TALE OF TWO DIETS

Sometimes it’s really obvious when a diet is unhealthy. If someone’s eating burgers for breakfast, fried chicken for lunch, and pizza and beer for dinner every day, then they’re probably not going to be the healthiest person on the planet.

But sometimes a diet looks healthy but isn’t delivering the sort of nutritional punch you want. One reason for this is that we’ve been conditioned to eat a pretty narrow range of foods, and to eat certain types of foods at specific times. Hardly anyone thinks it’s normal to eat vegetables at breakfast, for instance – but that’s crazy: why shouldn’t we eat veges at breakfast?

So, let’s take a look at a ‘healthy but conventional’ day of eating, and compare it with a ‘healthy but unconventional’ day – and see how the nutrition stacks up for each of them.

CONVENTIONAL HEALTHY

Breakfast:

Muesli (1 cup), yoghurt (175 g), milk (½ cup), blueberries (¼ cup), glass of orange juice (250 ml)

Morning tea:

1 banana

Lunch:

Two sandwiches with egg and lettuce, 2 kiwifruit

Afternoon tea:

Small bag of nuts (50 g)

Dinner:

Steak (186 g), boiled potatoes (175 g), peas (40 g), broccoli (60 g)

Dessert:

Fruit salad (1 cup)

Looks pretty healthy, right? But dig deeper, and see all the white food that’s in that day – muesli, banana, bread, potato. And there’s quite a bit of sugar from fruit, too – blueberries, orange juice, banana, kiwifruit and fruit salad.

Breakfast delivers 767 calories and nearly 70 g of sugars (some of this is lactose). Lunch is around 700 calories and 24 g of sugar (mostly from the kiwifruit). Dinner is 508 calories and just a trace of sugars. Snacks add another 591 calories and 58 g of sugar. For the day, then, we have 2566 calories and 152 g of sugars. Most of this sugar is not ‘added sugar’, so wouldn’t be counted under sugar intake recommendations – but it still contributes to your daily intake.

UNCONVENTIONAL HEALTHY

Breakfast:

2 poached eggs, grilled bacon (3 rashers), 1 grilled tomato, ½ an avocado, steamed spinach (½ cup)

Morning tea:

None needed

Lunch:

Large salad with quinoa (½ cup before cooking), mixed vegetables like beetroot, celery, capsicum, cucumber, tomato and snowpeas (2 cups), small can of tuna (95 g), herbs, and a dressing of olive oil (1 tablespoon) and balsamic vinegar or lemon juice (1 tablespoon)

Afternoon tea:

10 almonds

Dinner:

Steak (186 g), peas (50 g), broccoli (100 g), carrots (75 g), sweetcorn (75 g)

Dessert:

Dark chocolate (10 g), peanut butter (1 teaspoon)

Breakfast delivers 777 calories but hardly any sugar, which means that your insulin levels are going to stay steady throughout the morning and you’re not going to get the munchies at morning tea time. Lunch is roughly 555 calories, depending on what vegetables you choose to use – this will also affect the sugar content, but let’s assume around 10 g of sugar. Dinner comes in at 457 calories with 12.5 g of sugars, mainly from the carrots and sweetcorn. Snacks add up to 156 calories – the sugar content depends on how dark the chocolate is. If you choose 90% cocoa solids, there’s virtually no sugar in the chocolate. So for the day we have 1945 calories and 22 g of sugars. That leaves plenty of room for a glass of red, if you fancy it!

So what made the difference? Cutting out some of the white foods like bread and potato, and replacing these with more non-starchy vegetables. Also, removing concentrated sources of sugar like fruit juice. In fact, there’s no fruit in this plan. You could add a couple of plums at morning tea and still only add an extra 60 calories – although it would add nearly 14 g of sugars.