1 Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam

Terry E. Miller

The door is surrounded by a sea of shoes: even the audience must remove them and sit cross-legged on the floor. And this is no ordinary concert. At the front is a spectacular altar consisting of musical instruments arranged in multiple layers; even more striking is the central platform filled with masks, flowers, bowls of food and sundry mysterious objects. A group of young students come in and sit together, some giggling, others looking confused; the elderly ritualist enters and begins a monotone chant. When he has finished he announces the title of a composition to be played by the musicians arranged behind xylophones, gong-circles, drums, percussion and a thick wooden wind instrument: ‘Sathukan!’ (‘greeting the teacher’). Initially the music is a sweep of seemingly unrelated pitches, an outpouring of activity by each individual musician that is hard to grasp: despite the percussion, it’s difficult to perceive anything resembling a measure or a phrase. Finally, after many more such pieces, each student comes forward to receive a ritual ‘first lesson’ either on the large gong-circle or the flute, in which the teacher holds the student’s hands to simulate the playing of the piece. Each then receives a soot-mark on the forehead, and over one ear a piece of banana leaf with a flower. Having greeted the teacher (khru, guru in Thai) whose lineage extends to the gods themselves – since all knowledge derives from them – each student is now eligible to be instructed in music.

▪ History

To address the question of whether any music in mainland Southeast Asia can be called ‘classical’, we must first consider the term. ‘Classical’ is an English word that not only denotes a vast corpus of European and American music but carries connotations of hierarchy, value and sophistication. Applied to music in Thailand, Laos, Cambodia or Vietnam, it risks creating inappropriate associations, especially in the case of Vietnam, yet commentators from both Southeast Asia and elsewhere have long used ‘classical’ to describe this music. Just as the European elite were the patrons of Western classical music, in Southeast Asia the aristocracy, and especially the extended royal family, performed this function too. Add to that local perceptions of this music in those same terms of hierarchy, value and sophistication, and you may conclude that ‘Thai classical’ and ‘Lao classical’ are indeed appropriate.

Discussing the classical traditions of Thailand, Laos and Cambodia together makes sense. Not only do they have much in common, but their intertwined histories have created a more homogeneous style than most nationalistically-inclined commentators may be willing to admit. However, unlike these three cultures – all deeply Indianised through the influences of religion, language, literature, art and dance – Vietnam’s must be addressed separately because there Chinese influence was paramount. The Indianisation typical of the other countries only penetrated Vietnam through Chinese Buddhism, or as acquired from a conquered people – specifically the Cham – who now represent a minority culture in southern Vietnam. To understand all this requires some history.

To paraphrase an old saying, when they gave a war in Southeast Asia, everyone came. Over the two last millennia of the region’s history there have been many conflicts among the kingdoms and other political entities which have risen and fallen. It became customary that upon conquering your enemy, you not only destroyed his palaces and capital city, but you also carried off as much of his population as you could. Back home you forcibly resettled these people in under-populated provinces, to farm the land and provide labour for digging canals and moats, building walls, and even for fighting wars. It was also customary to bring the conquered court’s musicians, dancers, instrument makers, painters, poets and artists to the victorious capital, where the local culture would undergo a transformation, especially when the conquered culture was viewed as superior.

The first millennium CE saw the Khmer rise to prominence. When they were building their court and temple centres around Angkor in what is now western Cambodia, between the ninth and fifteenth centuries, the Viet were still divided, with many living far to the north in what is now China, while neither the Lao nor the Siamese (as the Thai formerly called themselves) had coalesced into political entities larger than villages. It was the Khmer empire, centred at Angkor, which became Southeast Asia’s first great kingdom, extending from southern Vietnam in the east to the Thai-Burmese border in the west, and to the northern reaches of the Central Thai Plain and part-way down the Malay Peninsula.

The rise of the first historical Siamese kingdom in the late thirteenth century, centred in Sukhothai, well north of modern Bangkok, coincided with a weakening of Angkor, and over the next three centuries there was near-constant conflict between the two. Siamese victories over the Khmer led in 1431 to the near-extinction of Angkor, after which this once-great kingdom sank into poverty and despair. Following custom, when the Siamese conquered the Khmer, they carried off much of the population, including most of their musicians, to be resettled in what is now Thailand. There is no way to know to what extent or in what ways the old Khmer musical culture transformed that of Siam, or whether the Thai preserve a repertory that was originally Khmer: our only evidence of Angkor’s musical past is seen in the stone bas reliefs of Angkor Thom and Angkor Vat, and few of these resemble anything found in today’s Thai music.

The first historical Lao kingdom, Lan Xang (‘Million Elephants’), blossomed only in the mid-sixteenth century. In 1767 the Burmese conquered the Siamese kingdom of Ayuthaya and forced much of the population, including musicians and dancers, into exile in Burma. Following this disaster the Siamese kingdom regrouped in Thonburi, across the river from present-day Bangkok. The Siamese king Taksin marched an army north to the Lao capital, Vientiane, in 1774, and laid waste to the city, forcibly bringing much of the population back to Thonburi, including the Lao royal family plus their entire music and dance establishment. Tensions between Bangkok and Vientiane continued. Rama III (1824–51), feeling threatened by an advancing Lao army, marched to Vientiane, levelled the city, and carried off virtually all of the population, resettling the majority in the provinces surrounding Bangkok, and others in the north-eastern provinces. At that point Lao court music ceased to exist, except for that practiced by the artists who remained in Bangkok. Thai music then resumed its development, continuing uninterrupted to the present day. During this long period of peace, Thai music, dance and theatre have achieved both depth and variety.

Angkor’s Bayon, part of Angkor Thom and constructed around 1200 CE, has numerous stone reliefs showing musical activity. From left to right: small cymbals with handles, a drum, a gong suspended from a pole and played by a disproportionately small figure, and a horn.

During this same period the court musics of Laos and Cambodia struggled to survive. Most Lao court musicians and dancers had been kidnapped and brought to Bangkok, and the Cambodian court, barely restored after the fall of Angkor, remained weak and modest since the French were colonizing ‘French Indochina’ (Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia). In 1930 a contingent of Thai court musicians, the most prominent being composer-performer Luang Phradit Phairoh, were sent to Phnom Penh to help restore Khmer court music. As a result, Khmer ‘classical’ music became a regional variation of Thai music – modestly distinct thanks to subtle differences in playing style and instrumental idiom – with Cambodia having no known independent tradition of composition. Lao court music was also re-established with Thai help, and many Lao musicians studied in Bangkok. Similarly, then, Lao music shows few distinctions from Thai.

Later both Lao and Khmer classical musics underwent second extinctions. When the Khmer Rouge overthrew the Cambodian King Silhanouk in 1970 and began a reign of terror during which some two million people died, around eighty per cent of the court musicians were wiped out, with only a few surviving and some fleeing to the West. A second restoration began in the late 1980s and has continued to the present, with the re-establishment of the Royal University of Fine Arts. Meanwhile in Laos, when the Pathet Lao overthrew the royalists and forced King Sisavang Vong to abdicate in 1975, the Lao court tradition was again dispersed, with the performers ending up variously in France, the United States and elsewhere, and unable to regroup effectively. For some years the communist government pursued a policy of condemning classical music, but during the 1980s a partial restoration began. Consequently performance standards in Laos have not yet returned to those of even the recent past.

It is important to understand that the above narrative is that of an outsider, and that some nationalist observers in Laos and Cambodia might disagree with parts of it, claiming either independence or an unbroken history for their respective musical traditions. Many Lao still resent the Thai invasions from the early Bangkok period, and many Khmer, seeking to restore their well-deserved national pride, have asserted cultural independence from Bangkok. Whether or not one accepts these nationalist interpretations, it remains possible – as well as desirable – to unify this discussion, using Thai music as the primary focus because of its long and uninterrupted history, its vast repertory, and its high level of sophistication.

▪ (Mis)understanding the music

The first time I heard Thai classical music, as a graduate music student on a visit to Bangkok in 1970, I could make little sense of it. I found some of the ensemble music ‘melodic’, but I could not understand the forms or the performance process, and the timbres were not immediately appealing. Much later I discovered a pamphlet written in 1884 by Frederick Verney, Secretary to the Siamese Legation in London during the visit by Siamese musicians to the International Inventions Exhibition. Verney noted that a great ‘stumbling-block’ for many Westerners in their attempts to appreciate non-Western music was education, which ‘precludes the possibility of a full appreciation of music of a foreign and distinct school… In order justly to appreciate the music of the East it would be necessary to forget all that one has experienced in the West.’1 This is wise advice in the case of Thai classical music, especially for its most advanced forms and genres, which even the most open-minded of listeners may find cacophonous at first.

Indeed Thai, Lao and Khmer classical music can be an acquired taste even for citizens of those countries: because most people listen to local popular music of some type on a daily basis, their norm is equal temperament, tonal harmony and the timbres of Western instruments such as guitar, saxophone or keyboard. But Thai also grow up routinely encountering their own classical music, usually in ‘serious’ or ritual situations such as the teacher-greeting ceremony. And whether they understand it or not, they associate it with important life-events, and with the soul of the nation and its culture. It stirs deep feelings in them; they feel proud when television programmes on national or royal matters use classical background music, and are profoundly moved by it at funerals. Though Thai studying abroad may not listen to classical music privately, most choose it to represent their culture to outsiders, sensing its inherent Thai-ness.

Alas, not everyone who encountered Southeast Asian classical music during the early centuries of contact (sixteenth–nineteenth centuries) found it either charming or meaningful. Giovanni-Filippo de Marini, an Italian Jesuit who visited the Lao court in 1666, wrote:

Different types of music preceded this pompous march coming out of the Palace of the King, but with so much confusion on their part, and from instruments so badly played, and from voices so rude and so discordant without observing bar lines, that there is heard absolutely nothing but noise and a confusing sound more capable of irking and deafening the people, than of being pleasant to the ear.2

Yet a French Jesuit who visited Ayuthaya, capital of old Siam, wrote in 1688: ‘There was nothing extraordinary, neither in the Musick nor Voices; yet the novelty and diversity of them, made them pleasant enough not to prove tedious the first time.’3 Some of the most vitriolic statements came later, from English-speaking diplomats and missionaries, such as the American Frederick Arthur Neale, who wrote in 1852: ‘I consider the Siamese music execrable; nor, indeed, is there any nation in the East that can be said to possess even the first rudiments of music.’4

▪ Creating the music

Although mainland Southeast Asia reflects profound influences from India in terms of language, literature, religion, dance and art, its music is fundamentally different from anything known in India today. Where Indian music emphasises individual artists, Thai emphasises ensembles. Where Indian music is generated through a complex modal system – embodied in the word raga – which provides the basis for composition and performance to happen simultaneously (what Westerners call improvisation), Thai music consists of fixed compositions by known composers, albeit with flexible instrumental idioms. Where Indian music emphasises individual virtuosity, Thai music emphasises cooperation, balance and restraint. Where raga creates dramatically-varied levels of tension and relaxation, Thai music strives for emotional evenness.

Thai classical music’s fundamental ensemble, the piphat (Lao, sep nyai, Khmer pinpeat), consists of tuned percussion, a single wind instrument playing melody, drums and a pair of small cymbals to articulate the metrical/rhythmic foundation. Minimally there are five instruments: (1) a xylophone (ranat ek) with twenty-one wooden or bamboo keys suspended on two cord lines over a boat-shaped wooden resonator; (2) a circular rattan frame supporting seventeen or eighteen horizontally-mounted bronze gongs (khawng wong yai); (3) a bulbous wooden wind instrument (pi) (in Western terms, an oboe) with a quadruple reed mounted on a short metal bocal at the upper end; (4) a horizontally-mounted drum with two heads played with the hands (taphon); and (5) a pair of small bronze cymbals (ching) which articulate the strong and weak beats of a closed metrical cycle of beats. For expanded ensembles, one adds a second (and lower-pitched) xylophone (ranat thum) and a second (higher-pitched) gong circle (khawng wong lek). Musicians normally use hard mallets (mai khaeng) because, historically, the ensemble played outdoors for ritual and theatrical events and needed to be loud. There is also a variant piphat ensemble using soft mallets for indoor performance (piphat mai nuam), but in this case there is a bamboo vertical fipple flute (khlui) and a coconut-body two-stringed fiddle (saw u) instead of the oboe. The soft mallet ensemble, however, is little known to the Lao and Khmer. The following table shows the equivalent names for the instruments.

|

Type

|

Thai piphat

|

Lao sep nyai

|

Khmer pinpeat

|

|

higher xylophone

|

ranat ek

|

lanat ek mai

|

roneat ek

|

|

lower xylophone

|

ranat thum

|

lanat thum mai

|

roneat thom

|

|

lower gong circle

|

khawng wong yai

|

khong vong nyai

|

kong vong thom

|

|

higher gong circle

|

khawng wong lek

|

khong vong noi

|

kong tauch

|

|

oboe

|

pi

|

pi

|

sralai

|

|

drum

|

taphon

|

kong taphone

|

sampho

|

|

cymbals

|

ching

|

sing

|

ching

|

Thailand has two other major ensembles, one paralleled in Laos and Cambodia, one not. The mahori ensemble consists of both xylophones and gong circles but is led (in its most proper form) by a distinctive three-stringed fiddle (saw sam sai) whose body is the bottom part of a coconut shell with three bulges pierced by a long spike neck. The bow is separate, but in moving from string to string the player rotates the fiddle slightly on its spike, rather than changing the bow angle. Because this instrument is probably the most challenging of all Thai instruments, many mahori ensembles omit it. Otherwise a mahori includes two two-stringed fiddles, the higher-pitched saw duang with a cylindrical body and the lower pitched saw u with a coconut body, both having the bow hairs pass between the strings. The wind instrument is always the khlui bamboo flute. The Lao equivalent, though without the saw sam sai, is called maholi or sep noi, and the Khmer equivalent is called mohori. The Thai ensemble without equivalent is the khrueang sai, a term meaning literally ‘stringed instruments’. Developed more recently – probably late in the nineteenth century – this ensemble combines the two-stringed fiddles and flute with several other possible instruments, including a crocodile-shaped zither (jakhe) and a hammered dulcimer originally borrowed from southern China (khim). All ensembles also include one or two drums plus the small cymbals.

In a mural illustrating the Thai version of the Indian Ramayana, a piphat ensemble performs at a noble house in Bangkok. While the murals at Wat Phra Kheo (Temple of the Emerald Buddha) are sometimes dated back to the eighteenth century, they have been continually repainted – and even re-imagined – up to the present day. From left to right: ( lower row) klawng tat drums, khawng wong yai gong circle, khawng wong lek gong circle, khawng mong gong, ching small cymbals; (upper row) ranat ek upper xylophone, pi reed, ranat thum lower xylophone, drum.

At Ta Prohm temple, an ancient Khmer ruin south of Phnom Penh near Tonle Bati lake, a pinpeat ensemble plays for visitors on a Sunday in 1989. From left to right: (left front row)sampho drum, skor thom drum pair; (middle row) roneat dek upper metallophone, roneat ek upper xylophone; (right) khong vong thom lower gong circle.

Regardless of whether listeners find the music meaningful, they cannot but be impressed by the appearance of the instruments. The two xylophones hang suspended over wooden resonator boxes, the higher xylophone’s box being boat-shaped on a pedestal while the lower one’s sits directly on the floor. Cases may be finished natural wood, but many are painted red or blue, with gold highlighting the patterned carvings; sometimes the circular rattan frames of the gong circles are also painted. The finest instruments, especially in the past, included parts made of elephant ivory; royal instruments could add extensive carving and even embedded stones along with the gold highlighting. The decoration of the instruments echoes the ornamentation of the music.

▪ Forms

All classical music in Thailand, Cambodia and Laos consists of fixed compositions, with most from the nineteenth century onward having known composers. In this respect, classical music in mainland Southeast Asia resembles that of Europe in principle, but not in process. Whereas a Western composer notates the work on paper in a more or less fixed form (the degree of detail varying from skeletal scores in the Baroque that allow for improvisation to the most detailed scores of the mid twentieth century), Thai classical composers notate nothing: their compositions are created in their minds and then committed to memory. Consequently knowledge regarding date, provenance and composer remains confined to oral tradition. Further, there being little sense of ownership and virtually no copyright law, composers have freely added new sections or variations to existing pieces, including by other composers, over the years. The key word is flexibility, a concept which permeates Thai life.

Because composers are also performers, most dictate their compositions to their musicians by first playing the fundamental form of the piece on the large gong circle (khawng wong yai). This version, luk khawng, is the least dense in terms of notes, but it is not the ‘original’ melody; it is simply the composition played ‘in the idiom’ (thang) of the gong circle, primarily expressed in single notes, octaves and pairs of fifths or fourths. On hearing this version, each musician then ‘realises’ that structure in the idiom of his/her particular instrument (e.g. into thang ranat ek – the higher xylophone). The work is only completed when the ensemble plays this ‘composition’ structure as a series of simultaneous variants, the differences deriving from each instrument’s idiom and the level of the musician’s skill. A given composition, then, could be ‘realised’ into an extremely complex form by advanced musicians, or into a simple form by beginners. Instrumental idioms are flexible, and could be described as a highly controlled process of improvisation on a fixed structure, somewhat analogous to jazz. Although this texture is a form of heterophony, scholars prefer the more precise term ‘stratified polyphony’ when discussing Southeast Asian music.

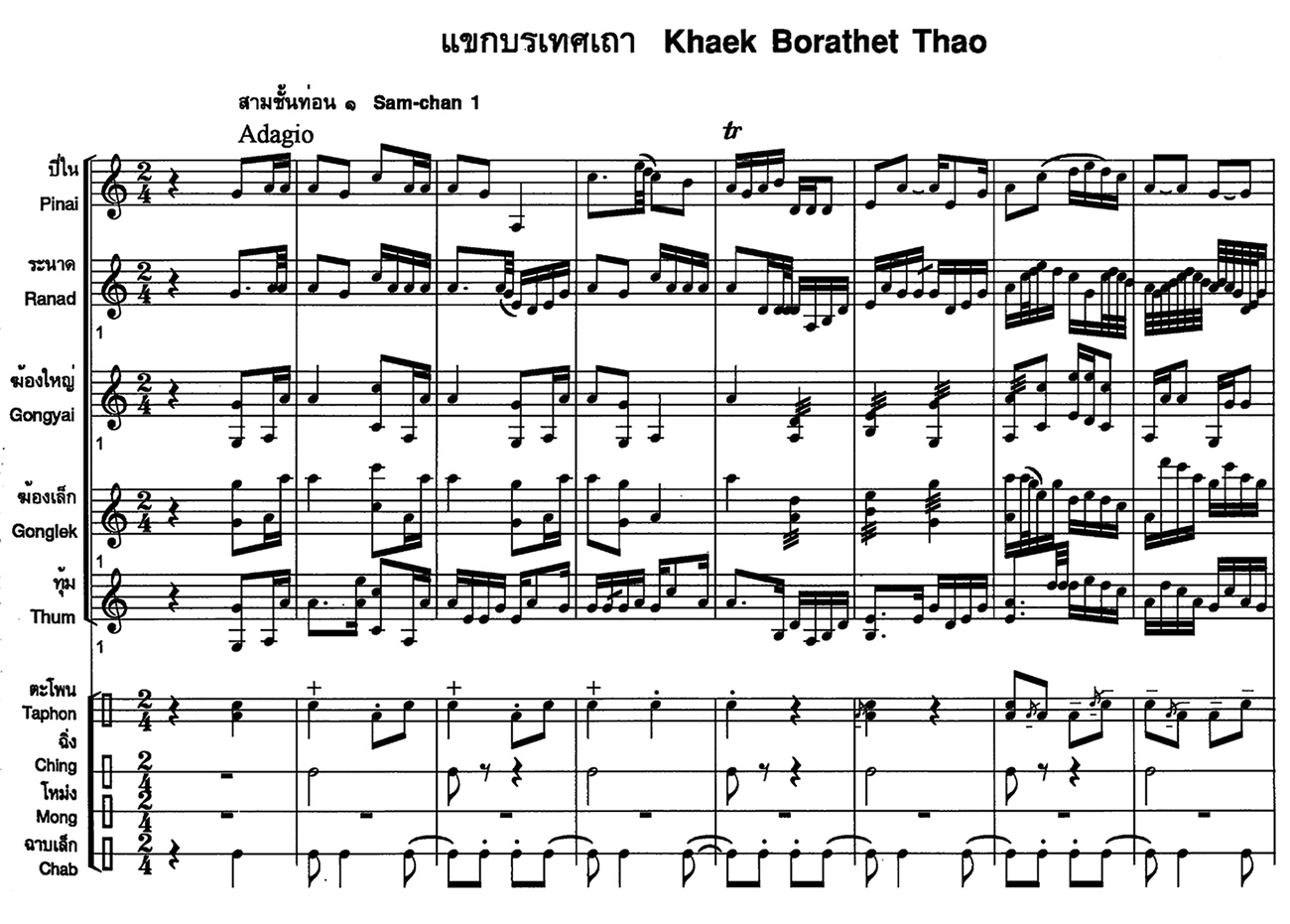

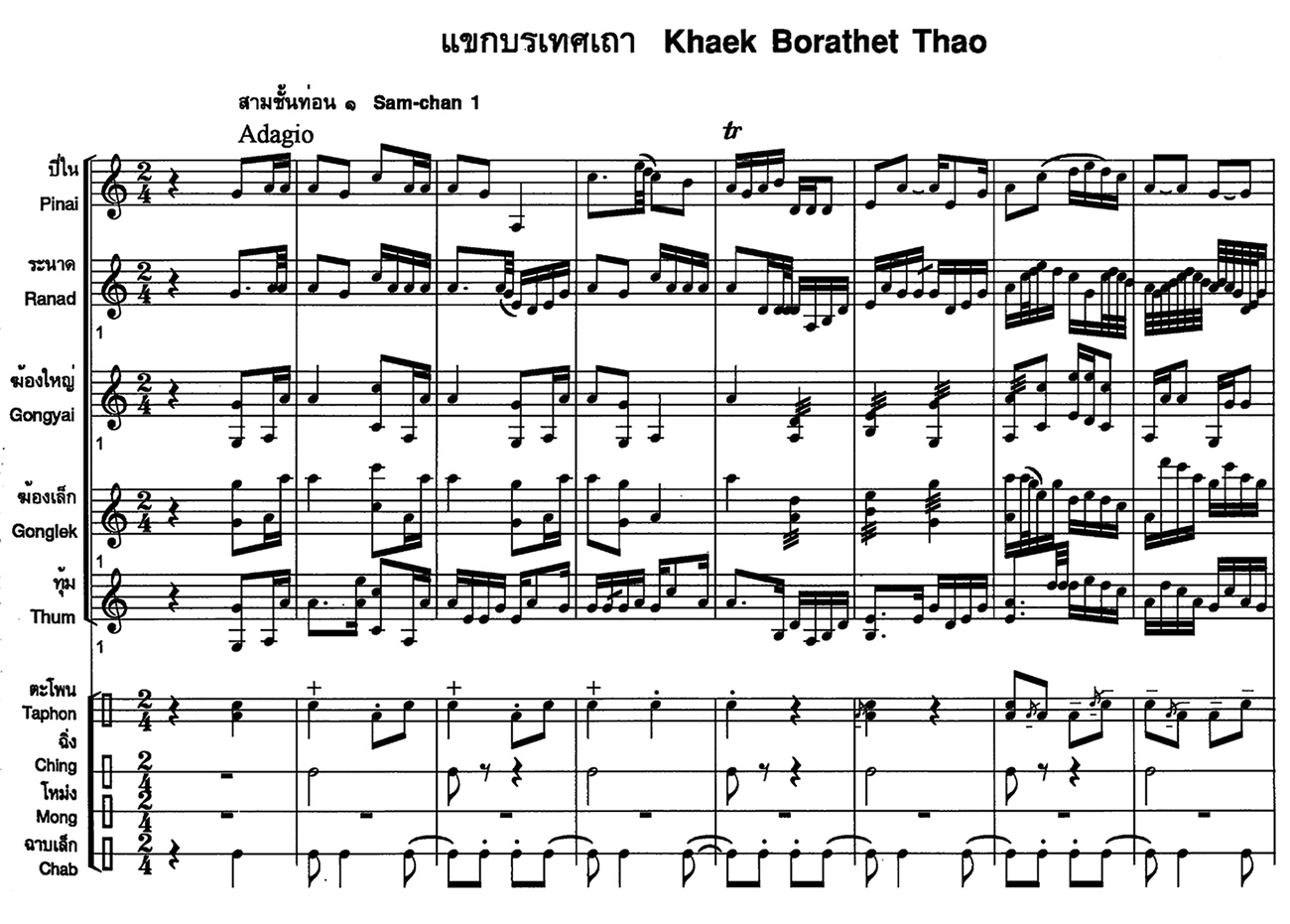

EX. 1.1 The first phrase of ‘Khaek Borathet’ transcribed into staff notation and showing the polyphonic stratification (or heterophony) and the instruments, each playing its own idiomatic version of the melody

Though composers trust musicians to complete a work through this process of idiomatic realisation, they maintain control of an astounding variety of forms and compositional techniques, many being of a complexity that requires detailed study in transcription in order to understand. Groups of compositions can be organised into suites (tap), some related musically and others organised for a specific situation, such as the teacher-greeting ceremony (wai khru) or a specific Buddhist ceremony for chanting in the morning (homrong chao) or evening (homrong yen). The highest class are ritual suites consisting of ‘action tunes’ (phleng naphat), so named because they are also used to accompany dance or action in classical theatre, including masked dance, large shadow theatre and some forms of dance drama. Most phleng naphat are highly motivic, with little clear phrasing and rarely anything resembling a ‘tune’; they unfold like a late European Baroque work, with an endless melody created through Fortspinnung. But there are also many suites – and independent pieces – consisting of shorter, tuneful compositions with clear phrasing, less differentiated instrumental idioms and colourful titles.

While some compositions have titles that indicate compositional techniques (for example, ‘Tayoi’, a complex pattern manipulating phrases into sub-phrases and motives) or formal patterns (for example, ‘Thao’, indicating that the basic melodic structure is presented in three ‘tempo levels’ – the original, expanded and diminished), most titles suggest a programmatic connection to something non-musical, such as nature, literature, Buddhism, love or history. Further, many composition titles are preceded with a word indicating ethnicity: khamen (Khmer), jin (Chinese), phama (Burmese), lao, mon or khaek (Muslim or Malay). These terms denote a complex of traits that may or may not have anything to do with the original, since all are by Thai composers and all are in Thai style. Nonetheless, each has its own scale or mode, its own metrical/drum pattern, its own melodic style, and often the use of a particular drum associated with its ethnicity. Perhaps the best known composition in the classical repertory is ‘Khamen sai yok’. ‘Khamen’ indicates its ‘ethnic’ characteristics (‘Khmer style’), and ‘Sai Yok’ alludes to a beautiful waterfall in Kanchanaburi province in western Thailand. The composition’s lyrics describe the scenery, the birds, the trees, the plants, and allude to the observer’s feelings, but not directly to Cambodia. ‘Lao siang thian’ is in the ‘Lao’ mode, while ‘siang thian’ (‘oracle of light’) alludes to a Buddhist festival in northern Thailand during which worshippers carry candles three times around a temple.

Most compositions also have a vocal version, typically sung with accompaniment by drum and small cymbals, before the instrumental version is played. Because Thai is a tonal language – where syllables must be inflected (high, low, rising, falling) – singers must correctly express the lexical tones while conforming to the skeletal structure of the composition. The vocal idiom, however, can differ so markedly from the instrumental version that it is not recognisable as the same composition. These discrepancies result from the added pitch inflections that clarify the lexical tones, along with the custom of adding textless melismas between words, especially in the ‘third tempo level’ where structural tones are spaced further apart in time. These melismas, called uean, are subtle flourishes similar to those played by the fiddles and the flute, sometimes almost under the breath: here resides the real art of Thai singing, not in the main tones. (The same is true of Lao singing, since Lao is also tonal; Khmer singing tends to be plainer, as Khmer is not a tonal language.)

Students learn to sing through imitation, and can start very young. One famous female singer, Suntharawathin, began learning from her father. She wrote:

When my speaking was clear enough, he started teaching me to sing ‘Ton phleng ching’, as it had to be the first song every beginner learnt. The first line was ‘kaki pongpat salat kawn’, but on the first day I learnt how to sing just the word ‘kaki’: ‘ka’ followed by uean and then ‘ki’. The sound of the uean must be the same as the trilling sound of the fiddle. I had to practise every morning and evening. Once I could sing that word, he taught me the next one, and so on until the song was complete.5

Vocal timbres, because they lack vibrato and are nasal and seemingly ‘pinched’, differ greatly from the ideals of Western singing.

Among the most creative Thai musical forms is a tripartite structure called phleng thao, ‘thao’ alluding to a set of nesting objects, similar to sets of Russian dolls or mixing bowls. The composition consists of three versions of the same melodic pitch structure played continuously, using three ‘proportional tempo levels’ (chan). First the composer creates the ‘second tempo level’ (sawng chan) and plays it on the large gong circle (khawng wong yai), because that is the simplest idiom of all the ensemble instruments. He then expands the structure to twice its length by adding notes between the main ones (this section is called sam chan or ‘third tempo level’), and reduces the structure to half its length by simplifying the idioms of the other instruments (chan dio or ‘first tempo level’). Other members of the ensemble “realise” both the original and the expanded/reduced versions in the idioms of their own instruments. Although the compositional process begins with the middle level, in performance the expanded or augmented form is presented first, followed by the original form and finally the diminished form, the whole often completed with a stock ‘coda’ (luk mot). The individual instrumental sections (or levels, chan) consist of more, fewer or no extra embellishing notes between the main structural pitches, making each ‘level’ sound like a different melody, though fundamentally each is the same. Thao compositions are therefore lengthy: the shortest of them requires at least ten minutes, but a long composition played fully in all three tempo levels including vocal parts could last more than thirty minutes. Phleng thao are free-standing compositions more often played by mahori and khruang sai ensembles than by piphat, and are among the most popular of Thai compositions.

EX. 1.2 A comparison of the melodic structure of a phleng thao composition entitled ‘Lao siang thian’, the respective versions coinciding on two structural pitches, G and D (circled). A circle above the staff indicates the undamped ‘ching’ stroke of the ching cymbals; a + indicates the damped ‘chap’ stroke; + in a circle indicates the ‘chap’ stroke on a structural pitch ending a cycle.

Thai compositions, while fixed in structure, allow each musician great idiomatic flexibility. Most instrumental sections require ‘repeats’, but skilled musicians rarely play a repetition as they did the first time: this is where improvisation is permitted. But there are limitations to this. The more melodic a composition, the fewer changes can be made. Ritual compositions, although highly motivic, cannot be varied at all, for this would threaten their spiritual integrity. Not all compositions are uniform in pattern, however. Within pieces, composers also alter texture, mood and tension by using a variety of named techniques. Many works include passages of antiphonal playing, where the higher instruments lead and the lower instruments follow: this may sometimes produce passages of contrapuntal polyphony. In luk law luk tam the answering instruments repeat antiphonally what the leading instruments play; in luk nam luk taw the following instruments complete a phrase begun by the leading group; in luk khat the groups play short passages – musical motives – in quick alternation while in luk luam they do the same, but overlapping. These give the music added excitement and forward drive. That all these procedures should be created orally, without the aid of notation, and memorised by thousands of musicians, is remarkable.

▪ Tunings, scales, modes

Like the music itself, Thai music theory remains unsystematic and largely unwritten. Beyond the descriptions of a few scholars – some Thai, some foreign – a comprehensive, logical explanation of Thai theory remains to be set down. Terminology exists, but terms such as thang have multiple meanings (idiom, school of a master, mode) both generally and musically. Ever since A. J. Ellis wrote his pioneering study of ‘the scales of various nations’ based on instruments housed in British museums in the early 1880s, the conventional wisdom has been that the Thai tuning system consists of seven equidistant tones. Using his ‘cents’ system, with 1200 cents in an octave, each Thai degree is therefore 171.4 cents, smaller than a Western equal-tempered whole tone (200 cents) and greater than a semitone (100 cents). While it is true that Thai instruments of fixed pitch are tuned to be functionally equidistant, allowing compositions to be played starting on any of the seven pitches, equidistant tuning is not encountered with the voice, winds or stringed instruments, except when they must conform with keyed percussion. Thus it is correct to say that the tuning of Thai music (and by extension that of Laos and Cambodia) is ‘in tune’ with itself, but sounds ‘out of tune’ to listeners conditioned to twelve-tone equidistant tuning.

Each degree of the seven-tone tuning system can be the starting pitch for a scale or mode, and each has a name. But a tuning system is not necessarily the same as a scale, and most Thai compositions are composed to pentatonic scales (pitches 1 2 3 5 6), though one class uses six. Some compositions, however, especially the ritual naphat ‘action tunes’ (because they are also associated with the masked drama), modulate freely, and thus the apparent use of all seven pitches does not indicate a seven-tone scale. Like the language, Thai melodies tend to flow in conjunct undulating motion and avoid large intervals. Each player embellishes the basic structure according to the conventions of his instrument. The lead xylophone (ranat ek) plays a continuous stream of notes, usually in octaves, in a density that doubles or quadruples the rate of notes on the large gong circle. The lower xylophone (ranat thum) plays a highly syncopated idiom involving many fourths and fifths, pitch displacements and rapid note-runs. The higher gong circle (khawng wong lek) plays an active idiom involving many rapid note-runs, fourths and fifths, and can often be heard above the fray because its high metallic notes penetrate well. The resulting polyphonic stratification can sound chaotic to inexperienced listeners, because each idiom is so different, and there is no regard for pitch congruence except at certain points, where these congruencies maintain the coherence of the rhythmic/metrical structure.

This is significant for several reasons. First, certain instruments clearly and audibly articulate the metrical/rhythmic structure, which is organised in closed cycles of beats, analogous to the cycle of time on a clock face. Virtually all Thai classical music is in duple metre, and when transcribed into notation appears to be merely continuous measures of two or four beats, conceived in cycles of two, four or eight measures. The final beat of each cycle, siang dok or ‘falling pitch’, is the strongest. The small bronze cymbals, onomatopoetically named ching after their ringing tone when struck together, articulate the metre, the undamped ‘ching’ stroke being the weak beat and the damped ‘chap’ stroke being the strong beat. Because the ‘chap’ stroke falls on the last beat of the cycle, Thai classical music is end-accented, unlike traditionally front-accented Western music.

Each cycle normally consists of four strokes: ching, chap, ching, chap. Melodic pitches sounded on ‘chap’ strokes are the most fundamental to the compositional structure, while those on the ‘ching’ strokes are of secondary importance. Thus, a composition consists of a skeletal structure of pitches sounded simultaneously with strokes on the ching cymbals, and this structure is played with little embellishment by the large gong circle. The other instruments play the same structure but, following their individual idioms, embellish it with a greater or lesser number of pitches. The idiomatic embellishments flesh out the more tuneful compositions and allow for a degree of flexibility that some might call improvisation. In the most tuneful pieces, that flexibility is limited by the melody, but in ritual naphat works, players are expected to play exactly the version/idiom taught them by their teachers.

Although there are no concerts of purely instrumental music analogous to the West’s symphony concert, listeners sometimes encounter a competition among ensembles whose leaders choose the most virtuosic pieces possible. Such competitions trace their roots at least to the early twentieth century when members of the extended royal family lived in great houses that included, besides the usual gardens, furniture and art objects, a resident classical ensemble. It was customary for these ensembles to compete in a more or less friendly manner, a custom that figures prominently in Ittisoontorn Vichailak’s 2004 film, Homrong (The Overture), one of the few Thai films to have been distributed outside Thailand with English subtitles.

A theatre group from Bangkok in 1900, in a photograph probably taken in Thailand prior to the ensemble’s departure for Germany, where they performed in the Zoological Garden in Berlin, and allowed the ethnomusicologist Carl Stumpf to make the recordings now preserved in the Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv.

A Thai piphat ensemble performs at a festival honouring a great teacher in Nonthaburi. The two drummers playing klawng khaek are seated in front because the piece showcases them. Behind are the gong circle players and in front the xylophones, with the double-reed stage-right.

▪ Preserving tradition

A comprehensive history of the classical musics of Thailand, Laos and Cambodia does not exist, and probably never will, because the documents necessary for such a history either do not exist or exist in distorted form. This is especially evident in the many descriptions of early Siamese music written by foreign visitors from the sixteenth century onwards. These documents shed an uncertain light, because the writers were rarely musicians themselves and often wrote negative and ethnocentric assessments of the music they heard (as seen earlier in this chapter). Less biased writers did at least describe instruments and performances they encountered. The most valuable early record is that of French ambassador Simon de La Loubère, whose 1691 report Du Royaume de Siam included illustrations of instruments and an attempt at transcription of a classical song with a phonetically written text that continues to puzzle Thai scholars, because the transcriber did not know Thai and could only guess at the sounds. Further, he had difficulty notating pitches because, first, Thai music is tuned equidistantly, and second, singers often slide among pitches. Even taken together these documents cannot support a reliable, chronological history of the development of music in Siam.

Moreover, scarcely any written documents of Siamese origin exist, partly because anything written before printed books would have been incised on palm leaf, and neither insects nor the climate permit such fragile documents to last long. The present author is currently exploring whether there is reliable historical evidence in the colourful murals painted on the inside walls of many temples, but because these were painted on dry plaster, few early ones survive: the oldest originated during the late Ayuthaya period, around 1675. While many survive from the Bangkok period starting in the early nineteenth century, it is often impossible to know whether restorations have taken place, or whether the artist was depicting musical activity accurately or in generalised form. For Laos and Cambodia, few such documents survive, and no one has yet explored them.

The limited evidence suggests that classical music flourished and continued developing during the nineteenth century, in spite of the efforts to Westernise Thailand initiated by Kings Rama IV (Mongkut) and Rama V (Chulalongkorn), who reigned in sequence from 1851 to 1910. Where Rama V’s long reign saw Thailand develop modern government and consequently escape the colonial designs of both Britain and France, the reign of Rama VI (1910–25) saw perhaps the greatest flowering of the classical arts, in both music and theatre, in the country’s history. This golden age resulted largely because Rama VI, far less interested in government than in the arts, not only patronised the arts but himself composed music and wrote theatre pieces; as the many princes and princesses of the extended royal family copied him, this led to the rise of new composers, the development of instrumental virtuosity, and the making of fine instruments. This was the period of Luang Phradit Phairoh, now considered Thailand’s leading classical composer and one of the greatest virtuosos in memory; his life also figured in the film Homrong. This ‘high Baroque’ of classical music, however, was not to last.

Following the Revolution of 1932, when the absolute monarchy of King Rama VII (1925–35) was abolished and replaced with a constitutional one, the vast court music establishment was transferred to a new government bureaucracy later called the Department of Fine Arts, where it continues to this day. After Rama VII abdicated in 1935, although the crown passed to a young Rama VIII, the monarchy ceased to be either powerful or relevant until the present king, Rama IX, Bhumibol (1946–) rebuilt the kingship, but without any special support for classical music. Democracy in Thailand has long been plagued with military meddling, if not direct military rule, and during the regimes of Field Marshall Plaek Phibun-songkhram, who governed between 1938–44 and 1948–57, Thailand underwent a forced Westernisation that included the near-banning of Thai classical music from public performance. For the country’s musicians and composers, this was a modern Dark Age. By the time I arrived in 1972, Thai classical music had been released from its prison but remained obscure, housed in the Fine Arts Department, or offered piecemeal like finger-food in restaurants to tourists. Music was not considered a fit academic subject, and only one college, Ban Somdet Chao Phraya, offered a degree in music education. Elsewhere, classical music could only be enjoyed by students as a music-club activity.

Yet classical music, dance and theatre flourish throughout Thailand today, and the past forty years have seen radical changes in their fortunes. By the late 1980s music had become accepted in academia, and most institutions of higher education now have music departments, often offering both Thai and Western specialisms, thus allowing the graduation of skilled players who have become teachers at all levels. Thai classical music is now known to virtually all the population, and tens of thousands of elementary and secondary students have participated in ensembles and dance. In addition there are many private ensembles playing at a remarkably high level: these operate in private homes, in conjunction with the police and army, or with support from temples.

The situation in Laos reflects a radically different history. As noted earlier, the monarchy was extinguished in 1975 by the communist Pathet Lao regime, during whose time the economy collapsed, relations with the Western world (the Soviet Union excepted) soured, and Laos was mostly closed to all but ‘Eastern Bloc’ visitors. The court was eradicated and what remained of ‘classical’ music was considered tainted by association; it became confined to private homes and a few temples, with neither visibility nor status. When I returned to Laos in 1991 the Fine Arts school in Vientiane was again operating, but at a low level, and the only musical activities in Luang Phabang, the former royal capital, took place in private homes. Over the next ten years, however, realising that international audiences would respond positively to Lao classical music and theatre, the Lao government began a modest restoration which continues today. The influence Bangkok once had on the Lao and their repertory has not disappeared: there is no known independent tradition in Laos. While the Fine Arts College in Vientiane is now operating vigorously, the restored music and theatre at the former palace in Luang Phabang, primarily staged for tourists visiting this UNESCO World Heritage City, is basic in comparison to that of Thailand or even Cambodia.

Cambodia’s recent history has been marked by more savage extremes. When the Khmer Rouge swept into Phnom Penh in 1975 and emptied the city of its population – much of which was murdered or died of starvation and disease – a few of the artists, musicians, dancers and instrument-makers fled to camps in Thailand, where they immediately began to recreate their music because they felt it represented the soul of their culture. Eventually most of these artists resettled in the West, with some managing to re-establish their art in exile. In 1979 Vietnam, allied with Khmer Rouge defector Hun Sen, invaded Cambodia and drove the Khmer Rouge into exile on the fringes of the country. When I visited Phnom Penh in 1988, well before tourists were allowed back in, I found classical music at the former palace to be slowly recovering, thanks largely to a small number of survivors, plus Australian aid and the work of the Australian ethnomusicologist Bill Lobban. We documented classical dance in the former dance pavilion of the ruined palace, and we heard about performances for the few tourists then able to visit Angkor, whose great temples reflected the glories of the long lost Khmer Empire. Since then, with the restoration of the monarchy in 1993 under King Norodom Silhanouk, and now under his son King Norodom Sihamoni (2004–), the University of Fine Arts has been reconstituted as the Royal University of Fine Arts. Much that was lost has been restored, including the classical ensembles, dance and masked drama.

The social status of classical musicians in Southeast Asia depends on a variety of factors. In Thailand it differs between musicians who only perform, and those who teach as well. The former, especially those employed by the Fine Arts Department, willingly endure social prejudice – that they may be unreliable, drunkards, rebellious, poor marriage risks – but those who teach are universally respected, enjoying higher status than musicians who play commercially. In Laos and Cambodia, where so many musicians fled or were killed, the senior players who survived are venerated as carriers of a vital tradition.

Moreover, the classical traditions of Thailand, Laos and Cambodia are exceptionally conservative. In contrast to the Chinese musicians induced by progressive movements to ‘improve’ and ‘develop’ both their music and their instruments, Thai musicians, despite extensive modernisation and Westernisation, have chosen to change nothing. Tuning technologies, one of the first indicators of ‘improvement’, remain what they have been for centuries. For example, players tune the xylophones and gong circles by adding or removing a mixture of lead and wax applied beneath the keys or gongs. A few composers have offered works that combine Western instruments with Thai, but neither the works nor the clash of tuning systems have become popular. Today’s composers – and they are relatively few – continue to create works that are indistinguishable from the works of the past. Innovation is a non-issue in Cambodia and Laos, where simple restoration of the traditional music has been the goal.

▪ Performance contexts

In Thailand there are plenty of opportunities to hear classical music, though performances are rarely publicised. Tourists are most likely to encounter it as part of a cultural show at one of the major tourist attractions such as The Rose Garden, the Ancient City, or one of the many restaurants that offer foreigners a ‘spicy’ (but actually mild) Thai dinner followed by a show that includes de-contextualised snippets of masked theatre, dance drama, sword fighting and folk dance. Astute travellers may discover performances at the National Theatre, or find their way to a new theatre in Bangkok’s Chinatown where masked drama is performed throughout the year.

But one is more likely to encounter classical music as accompaniment to dance and theatre than as solo performance. These forms include the masked theatre (Thai khon, Lao Pha Lak Pha Lam [after the main characters], Khmer lkhaon khaol), the large shadow theatre (Thai nang yai, Khmer sbek thom), and rarely (mostly in the past) other forms of puppet theatre. Dance drama (Thai lakawn, Lao lakhon, Khmer lkhaon) also requires classical accompaniment, and – although considered debased – two other Thai genres use classical music: the popular likay theatre, and a kind of dance-drama (lakawn jatri) seen at a few temple shrines, especially the ‘city pillar shrine’ (lak muang) in Bangkok, the Erawan Shrine in Bangkok, and at Wat (temple) Mahathat in Phetchaburi.

Many schools have student ensembles which give concerts and participate in competitions, but the crucial event in education is the teacher-greeting ceremony held annually in all schools where classical music is taught. These ceremonies reflect the belief that the ‘gods’ – a vaguely defined pantheon from Hinduism, animism and folk Buddhism – are the source of all knowledge. And because teachers transmit this sacred knowledge to students, they must also be revered: traditionally students must keep their heads lower than that of the teacher, and because instruments are integral to this process, all must treat them with respect, never stepping over them, pointing one’s foot at them, or treating them roughly. Classical music and those who transmit it are held as quasi-sacred.

▪ Vietnam

Describing the traditional ensemble and theatrical music of Thailand, Laos and Cambodia as ‘classical’ may make sense, but there is little music in Vietnam so clearly analogous to the Western notion of ‘classical’. Unlike the countries discussed above, Vietnam was profoundly influenced by China rather than India, and, because of its status as a Chinese vassal state for much of its earlier existence, followed by French colonization, its dynasties and courts tended to follow Chinese examples first and the European conservatory model later. In addition, China had nothing comparable to the classical music discussed above, and does not form part of the Southeast Asian gong-chime world. One could argue that the court music of the Nguyen dynasty centred in imperial Hue’s ‘forbidden city’ from 1802 to 1945 constituted Vietnam’s classical music, but this was found only at the court, was reserved for court functions, and was not diffused to the broader population, nor even to the aristocracy. What music and dance survived the end of the Nguyen dynasty in 1945, when Emperor Bao Dai abdicated, was at least maintained as a cultural institution until 1968, when the disastrous ‘Tet offensive’ saw the near-total destruction of Hue, the death of most of the court musicians, and the silencing of this music until its restoration began in 1993; it continues today with UNESCO help.

In a mural illustrating the Thai version of the Indian Ramayana, a piphat ensemble accompanies a performance of nang yai (large shadow puppets) for the funeral of Piphek, in Bangkok’s Wat Phra Kheo (Temple of the Emerald Buddha). From left to right: klawng tat drums, pi reed, khawng wong yai gong circle, ranat ek upper xylophone and taphon drum.

Identifying other Vietnamese musical genres that might qualify for designation as ‘classical’ is still possible, because Vietnamese musicians have evolved a subtle and complex method of generating music, along with genres that require sophisticated musicianship. But it is also true that both aspects can be practiced by musicians ranging from master artists and ‘professors’ to merchants and farmers. This is because much of Vietnam’s most developed music is regional chamber music, created and performed by non-professionals whose training may not have gone beyond informal lessons from family members or local practitioners. These chamber genres are also echoed in theatrical genres, with at least those in the central region (tuong theatre) and the north (cheo) having a level of artistic development that would justify inclusion as ‘classical’.

While it is true that Vietnam was long under Chinese influence or control, and that many Vietnamese instruments have Chinese equivalents, several factors differentiate Vietnam’s music from that of China and suggest India as a possible source. These are the highly developed modal system for generating music, and the presence of extensive improvisation, neither factor being a part of the Chinese musical world. Elsewhere in Southeast Asia, although there are simple modal systems (e.g. Java’s pathet system), free improvisation is either non-existent or restricted to instrumental idiomatic variation. The only exception is the khaen free-reed mouth organ of northeast Thailand and Laos, which has a moderately developed modal system (lai) to support improvisation, but it is still far simpler than that of Vietnam.

Vietnam’s modal system, denoted by the term dieu, is a complex of all the elements needed to generate music, both in composition and improvisation (the latter actually being composition simultaneous with performance). These include tonal material (pitches organised into scales), typical melodic motives, required ornamentation, a generalised mood, cadential formulas and other subtleties appreciated by connoisseurs. The modal system has been extensively theorised in writing, though different scholars offer varying rationalisations and orders. Each modal scale has a name and each is fundamentally pentatonic, but the only degrees that are fixed and consistent are 1 and 4, the others being variously above or below Western tempered pitches, which results in Vietnamese music sounding somewhat out of tune to ears accustomed to Western tuning. However, these very particular pitch levels are necessary, both for the realisation of the mode and to satisfy the demands of the art.

As for instruments, the Chinese-derived fretted ones preserve the more rigid tuning of Chinese scales, but, to accommodate the Vietnamese modes, instrument-makers use exceptionally high frets and loose stringing that allows for the string-pulling necessary to realise flexible pitches. Musician and scholar Nguyen Thuyet Phong explains this matter in reference to the dan nguyet (moon lute with long neck), a two-stringed instrument with these high frets: ‘Because the dan nguyet is fretted, there are fixed pitches. The Vietnamese modal system, however, is exceptionally complex, requiring a great number of pitches beyond those produced by the frets. These are not merely ornamental or passing pitches, but ones absolutely basic to a given scale.’6 This is also true of the Vietnamese version of the Spanish guitar, where makers scoop out the wood between frets to give players the space for string-pressing. With unfretted stringed instruments and aerophones (flutes and oboes), players can stop strings where they wish, or ‘lip’ pitches to create the tuning.

Vietnamese musicians who specialise in the sixteen-string zither (dan tranh), the monochord (dan bao), the moon-shaped long-neck lute (dan nguyet), the Vietnamised guitar (luc huyen cam), the two stringed fiddle (dan nhi/dan co) and the horizontal flute (sao) are often capable of playing solo modal improvisations. Normally begun unaccompanied and non-metred, the metred sections, including the playing of relatively fixed named compositions, are organised within metrical cycles articulated by a clapper. Usually the song lang (a wooden slit gong with a beater attached to a springy piece of buffalo horn) is used but the sinh tien, consisting of three long flat pieces of wood, two of which are hinged, can also be employed. In the case of the latter, the lower piece has teeth cut into its lower side and a separate piece of wood is used to scrape along these teeth, causing several coins mounted on a nail on the upper piece to rattle. The song lang clapper plays infrequently, only on certain fixed beats according to the particular cycle.

Ca hue, the traditional chamber song of Vietnam’s central region, is usually performed on a covered boat while floating down the Perfume River west of Hue. The singers are accompanied by a chamber ensemble including a lute, zither, flute and monochord. Pairs of teacups are played like castanets by a female singer.

Vietnamese chamber music played on the dan nguyet lute and dan tranh zither

▪ Chamber music

Vietnam is considered to have three regional cultures, the south, central and north, based around Ho Chi Minh City, Hue and Hanoi respectively, each with its own distinctive forms of theatre and chamber music. Though chamber music best exemplifies the idea of ‘classical’ in Vietnam, none of these are professional activities, with most performers being amateurs who join clubs where the purpose is to sing sophisticated poetry with instrumental accompaniment. In the north, ca tru is rarely heard outside club meetings or competitions: the accompaniment is provided by an exceptionally long-necked lute with a trapezoid body called dan day, while the singer plays the phach, a wooden base struck with two beaters; during the performance a ‘critic’ responds by beating a small drum and calling out stock praises or criticisms. In the central region, ca hue songs are customarily sung on small boats floating on the Perfume River west of Hue, the former imperial city: accompanying musicians, typically five, play the zither, fiddle, various lutes and perhaps a flute and monochord. In addition someone, even a singer, plays a small pair of wooden clappers or a pair of ceramic tea cups. Thanks to tourism in Hue, now a UNESCO World Heritage City, there are public opportunities for hearing ca hue, and some performers earn a living playing for tourists. In the south, especially in the Delta of the Nine Dragons (Cu Long, or in English the ‘Mekong Delta’), the chamber genre is nhac tai tu (‘music and songs of talented persons’), which is normally encountered in club settings; accompaniment is provided by a small ensemble which may include fiddle, lute, guitar, zither, flute or some other melodic instrument.

Refined though these genres are, both in terms of poetry and music, they are performed by non-professionals including housewives and farmers. As a result, they are viewed by the general public as recreation rather than art, though each genre has its connoisseurs. Outsiders can argue that Vietnam’s chamber music meets many of the criteria for classification as a ‘classical’ music, but perhaps because Vietnam was a colony of France and received the tradition of European music conservatories that taught only Western classical music, few Vietnamese would see the equivalence, or agree to apply the term classique to this music.

Guide to pronunciation

Thai. To avoid complication, we do not indicate tone. Words sound according to standard pronunciation except for the following: t, k and p indicate unaspirated sounds, which sound slightly percussive. Th, kh and ph are aspirated and sound as in ‘tango’, ‘can’ and ‘Paris’. Final consonants are not clearly articulated but spoken sotto voce. Thus piphat sounds approximately ‘bee-pa(t)’. The letter ‘u’ is sounded as in ‘you’. The combination ‘ue’ approximates the sound of a German umlaut as in ‘ü’.

Lao. The ‘V’ in Lao (e.g. in Vientiane) sounds halfway between a ‘v’ and a ‘w’. The ‘X’ (e.g. in Xieng Khouang) sounds ‘s’. The combination ‘ou’ is sounded as in ‘you’. Because Lao has no ‘r’, equivalent words in Thai that have ‘r’ change to either ‘h’ or ‘l’ in Lao; for example, mahori (Thai) becomes maholi (Lao).

Vietnamese. Although first written in Chinese characters, Vietnamese came to be Romanised in Latin script in the seventeenth century following the work of French Jesuit Alexandre de Rhodes. This system, called quô´c ngũ,or ‘national script’, is standard today. A complex system, showing both tones and exact pronunciation of consonants and vowels, it still requires readers to know regional pronunciation differences. A ‘d’ without a horizontal line is ‘y’ in the south and ‘z’ in the north, while the ‘đ’ sounds ‘d’. A ‘t’ sounds as an unaspirated ‘d’. A ‘tr’ (as in dan tranh) sounds closer to ‘ch’, while ‘s’ (as in sao) sounds ‘sh’. A ‘ph’ (as in phach) sounds ‘f’.

Further reading

For a variety of reasons – extended wars involving Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos being one of them – there is little scholarship on the court/classical music of mainland Southeast Asia. Vietnam, however, has a long tradition of local scholars (the pioneer being Tran van Khe), which has now expanded to include Western and expatriate scholars as well. Thailand’s music was most thoroughly covered, based on the work of David Morton beginning around 1960, although his focus was on analysis rather than the broader musical culture. No one seems to have specialized in the classical music of Laos, while that of Cambodia has been written about primarily by one scholar, Sam-ang Sam, a native of Cambodia. Classical Cambodian dance has attracted far more attention than has the music. The best comprehensive studies are found in the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians and Garland Encyclopedia of World Music vol. 4 (Southeast Asia). Patricia Shehan Campbell has contributed three studies (Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam) for the classroom, each co-written with a local scholar. Thanks to the old tradition of French scholarship within its ‘Indochinese’ colonies, numerous studies of dance and music were published during the first half of the twentieth century. Since Morton’s retirement, the present author has been the leading scholar writing about Thailand’s classical music, and to lesser extents, those of Cambodia and Laos as well.

Recommended listening

▶ Cambodia

Cambodge: Musiques du Palais Royal (Années soixante), Ocora C 560034, 1994. Recorded at the palace in 1966 and 1970.

Cambodia/Cambodge: Royal Music/Musique royale, Auvidis D 8011, 1989. Originally recorded in 1971 by Jacques Brunet before the Cambodian holocaust.

Les musiques du Ramayana vol. 2, Cambodge, Ocora C 560015, 1990. From the masked dance drama Reamker performed in France in 1964.

The Music of Cambodia, vol. 1, 9 Gong Gamelan: Royal Court Music/Solo Instrumental Music; vol. 2, Royal Court Music; vol. 3, Solo Instrumental Music, Celestial Harmonies #13074/5/6-2, 1993.

▶ Laos

The Music of Laos, Rounder CD 5119, 1999. Reissue of a 1960s vinyl album from Baerenreiter.

Traditional Music of Luang Prabang (2 CDs), Bangkok: College of Music, Mahidol University, 2000.

Laos: Musique de l’ancienne cour de Luang Prabang/Music of the Ancient Royal Court of Luang Prabang/Tiao Phün Muang, VDE–Gallo CD-1213, 2008. The restored music of the former court in Luang Prabang, but the musicianship is modest.

▶ Thailand

Thai Classical Music Performed by the Prasit Thawon Ensemble, Nimbus NI 5412, 1994. The piphat mai kaeng (hard mallet) ensemble is led by national artist Prasit Thawon.

Royal Court Music of Thailand, Smithsonian-Folkways #40413, 1994.

Siamese Classical Music, vol. 1, The Piphat Ensemble before 1400 AD; vol. 2, The Piphat Ensemble 1351–1767 AD; vol. 3, The String Ensemble; vol. 4, The Piphat Sepha; vol. 5, The Mahori Orchestra, Marco Polo 8.223197–8.223200 and 8.223493, 1991–2 and 1994.

▶ Vietnam

Eternal Voices: Traditional Vietnamese Music in the United States (2 CDs), New Alliance NAR CD 053, 1993. Recordings of Vietnamese musicians in the United States with extensive notes by Phong Nguyen and Terry Miller.

Viêt-Nam: Le dàn tranh: Musiques d’hier et d’aujourd’hui, Ocora C 560055, 1994.

The Perfume River Traditional Ensemble, Music from the Lost Kingdom: Hue, Vietnam, Lyrichord LYRCD 7440, 1998.

Vietnam: Mother Mountain and Father Sea: An Introduction to the Traditional Music of Vietnam (6 CDs), White Cliffs Media, 2003. Covering all regions of Vietnam including the Central Highlands, with a 48-page booklet by Phong Nguyen and Terry Miller.