6 North India

Richard Widdess

The man in the silk shirt raises his outstretched hand towards the younger of the two sitarists seated before the small audience, and says ‘Wah!’ The musician pauses momentarily to acknowledge the compliment by touching his forehead, before repeating the admired phrase. This time it’s extended with a new twist, and continues seemingly unstoppable, rising, falling and unexpectedly rising again to reach new heights before eventually subsiding towards the tonic note. Foreseeing this conclusion, the audience bursts out with a chorus of ‘Wah! Wah! Shabash! [very good] Kya bat! [wonderful]’ which almost drowns the final notes.

The tabla accompanist, waiting his turn to play during the free-tempo introduction, shakes his head in approval. The elder sitarist says nothing, but his eyes gleam with pleasure at his son’s improvisation, which his own fingers soundlessly follow on own fret-board. Now he throws the young man a new challenge: a phrase that, instead of starting low, rising to a peak, and falling to its starting point, does the opposite. In reply, his son repeats his father’s rising conclusion, but brings it to a low ending.

The audience is again delighted. The man in the silk shirt, without whose presence in the front row no house concert in this part of town is considered complete, turns to his neighbour and mutters: ‘Such mastery! And he is so young!’

‘INDIAN classical music’ is a familiar concept. While it is necessary to distinguish the music of North India and its neighbours – principally Pakistan, Nepal and Bangladesh – from that of South India, both have become seen as parallel traditions of ‘Indian classical music’. This is a result partly of international tours by Indian concert musicians, and partly of the settlement of diasporic South Asian communities in many areas of the West. This chapter concerns North Indian, or Hindustani, music.

In India, ‘classical’ music is sharply distinguished from other types of music including folk music and popular music (such as the music of Bollywood movies), though it overlaps with dance, certain forms of which are also called ‘classical’, and with some types of religious singing, which are not. Our opening vignette illustrates several aspects of what is considered ‘classical’ about Hindustani music. It is music played (or sung) for the delectation of an attentive audience, typically drawn from an educated, wealthy, urban social elite. Such listeners ideally display sophisticated connoisseurship, based on extensive listening to the best artists, and sometimes on first-hand experience of learning to sing or play. They admire the musical knowledge, artistry and skill of individual soloists and accompanists, many of whom are professionals. The music is governed by a system of melodic and rhythmic modes (rāga,1 tāla) and a choice of traditional styles and forms, which allow shared understanding of what is expected, acceptable and exceptional. This system is largely independent of writing; although notation is used for some pedagogical or theoretical purposes, performance depends entirely on memory and creativity.

Music is created in real time by the performers; it is not the ‘work’ of a separate composer, and any pre-composed item such as a traditional song will constitute only a small part of the performance. ‘Improvised’ elaboration (upaj), within the constraints of raga and tala and the appropriate style, predominates, leading to the kind of inspired interaction between performers described above. Musicians and audiences alike stress the importance of oral tradition as the only means of transmitting Hindustani music that leads to outstanding performance; the key to this process is the close relationship over many years between teacher (if Hindu, called guru; if Muslim, ustād) and student (shishya or shāgird respectively), a relationship that is often likened to the transmission of religious knowledge and practice. Sometimes the teacher is also the father – less often, the mother – of the student.

Indian classical music is believed to be a form of knowledge and practice that has been continuously maintained and refined by successive generations of teachers and pupils, transmitted from time immemorial. One of the earliest literary accounts of musical performance, the Guttila Jātaka from around the third century BCE, sounds uncannily familiar, for it already embodies enduring characteristics of Indian classical music. In this Buddhist story, Guttila is a highly respected court musician to the king of Banaras, then as now one of the principal centres of musical art in North India. The instrument he played, the vīnā, would have been an arched harp similar to the saung-gauk of Burmese music, though this has long since been replaced in India by other instrument types. Musila is a no-hope student from Ujjain whose playing initially sounds like rats scratching a mat. But Guttila is a generous and conscientious guru and teaches Musila everything he knows. Eventually he finds himself challenged by the ungrateful Musila in open competition for supremacy at court. Feeling old and vulnerable, and fearing to be outshone by his own pupil, Guttila shrinks from the contest. But the gods intervene, and instruct Guttila to break the strings of his vina one by one, continuing to play on those that remain. To the astonishment of the listeners, Musila is able to replicate this feat, until finally Guttila breaks the last string. Ethereal music continues to pour out of his instrument, but Musila’s is mute, and the audience drives him out of town for his presumption.

This tale embodies the conception of music, still current today, as a form of unwritten, non-verbal knowledge. Such knowledge can only be acquired from a guru, not through the efforts of the student alone. The guru should transmit his knowledge to disciples who in return must show commitment, respect and loyalty to him. Competition for patronage between bearers of such knowledge is endemic among musicians today, in the politics of self-presentation and manipulation of audiences, agents and media. Competition also occurs on stage: in a friendly form, almost any performance can involve competitive exchanges between performers. Audiences are easily impressed by the precocity of young prodigies, but they deeply respect the knowledge and artistry of senior musicians, even those no longer at the top of their technical form. And musical sound is widely believed to have a spiritual or god-given aspect, as a result of which musical knowledge is typically treated as a form of sacred knowledge akin to religious scripture or philosophy. The moral dimension of musicianship which Musila singularly lacked is essential to conveying music’s deeper spiritual meaning.

‘Ragamala’ means ‘a garland of melodies’. Designed as adjuncts to musical performance, these miniatures evoked the music’s mood and often provided stories to accompany it. (Nata Raga, folio from a dispersed Ragamala series, Deccan, India, about 1690. Paper, opaque watercolour, gold. 35.2 × 23.7 cm.)

That meaning can be interpreted in a variety of ways, according to individual preference. In ancient philosophy the sound of music shares with that of ritual mantras the power to control the material universe; even today ragas should still be performed at the appropriate time of day (which may be any hour from early morning to late night) or season of the year to be in tune with the natural world, and are sometimes credited with supernatural powers, such as causing rain to fall or trees to flower. At a religious level music is a channel of communication between the devotee and his chosen deity, whether Krishna or Ram, Shiva or the Goddess. The aesthetic of classical music is explained in terms of rasa, the ‘juice’ or ‘essence’ of an emotion (such as love, mirth or compassion) that the listener tastes; this aesthetic experience is believed by Hindus to lead to spiritual liberation (moksha), or in the Sufi (devotional Islamic) tradition to an ecstatic yearning for union with God (sama). The assumption that music evokes emotion is suggested by the choice of the Sanskrit term rāga (pronounced rāg in Hindi), meaning ‘passion’, for the central melodic concept. The performer’s self-immersion in a single raga for an extended period of time is sometimes seen as a quasi-meditative state that the listener can only partly share; in his improvisation, the raga, conceived as a semi-divine being existing outside the performer, takes control of the musician, rather than the reverse, and flows through him to the listener. It is above all the concept, system, practice and experience of raga that makes Hindustani music ‘classical’.

▪ Raga and tala, composition and improvisation

A raga is what musicians announce they are playing, and what connoisseurs enjoy recognising even if it is not announced. A raga is a map of that melodic terrain that lies between scale and tune. It is not a scale: there can be many ragas in the same scale. Nor is it one specific tune: there can be many tunes in one raga. The essence of a raga can be heard in any of its tunes; but a full-length performance of the raga will include not only one or two composed pieces, but also extensive improvised passages, all of which will conform to and explore the features of the raga ‘map’. Such improvisation often includes an opening prelude, the ālāp, in which the performers gradually unfold the melodic features of the raga and which can last anything between a minute and an hour.

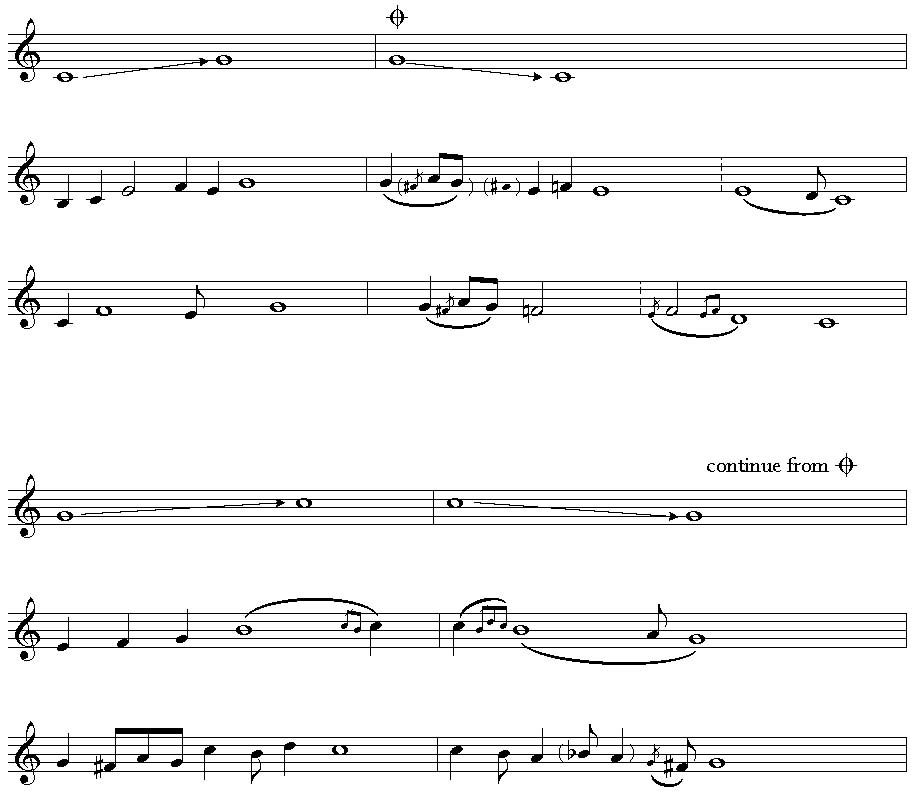

Bihāg is a famous raga traditionally performed in the evening. Its scalar material resembles the Western major scale, plus a sharp fourth in some phrases. In Example 6.1, the tonic is represented as C, though this pitch is not fixed but is chosen by the soloist. This note, together with the fifth, in this case G, would normally be sustained throughout the performance on a drone instrument, and also sounded repeatedly on the drone strings of the sitar. This drone, which one hardly notices once the performance is under way, anchors the raga to a constant reference point, and enables the musicians to judge the tuning of each note with pinpoint accuracy.

Example 6.1 shows typical ways of moving in raga Bihag, from tonic to fifth and back, and from fifth to upper tonic and back. It also shows, for comparison, corresponding melodic moves for raga Kedār, another evening raga, in which almost the same scalar material is used, but different pitches are emphasised, and different ways of moving from one point to another are employed. It is these typical phrases of the raga that the connoisseur listens for, and a phrase that perfectly brings out the unique melodic character of the raga will elicit an appreciative ‘Wah!’ So here we see that the ascent from tonic to fifth in Bihag goes (typically starting from the seventh degree rather than the tonic itself) B–C–E–F–E–G, with particular emphasis on E, the strongest note of the raga; whereas in Kedar one starts with a bold leap from C to F (which is a strong note in this raga), and proceeds via the merest suggestion of E direct to G. In both ragas, the second degree (D) is omitted from this ascending movement; but it appears in the corresponding descent, as a weak note in Bihag, and a strong one in Kedar. Both ragas include F# as a weak note, but the way of combining this note with the adjacent notes is slightly different.

EX. 6.1 Basic moves in ragas Bihag and Kedar

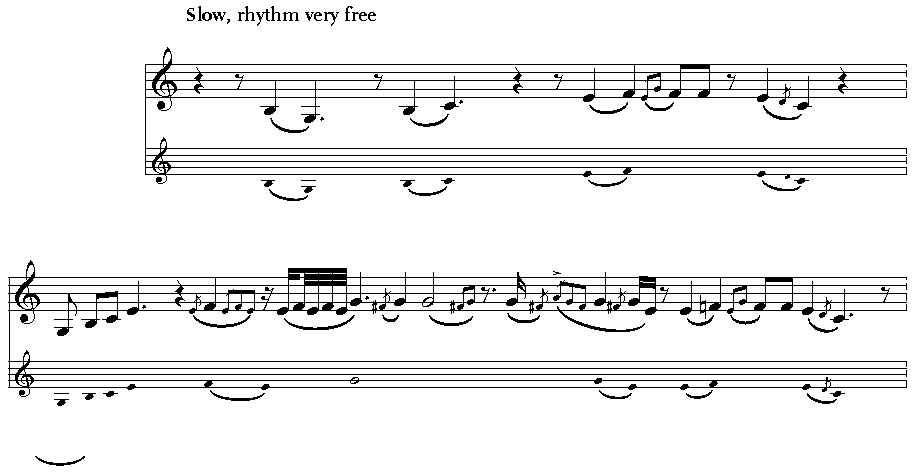

Example 6.2 represents the opening two phrases of a short alap in raga Bihag, as played on the sarod by Buddhadev Dasgupta.2 It illustrates how the raw materials of a raga (here corresponding to the second line of Example 6.1) can be used to develop a musical argument: the second phrase is an ‘expansion’ (vistār) of the first. In particular, the note E is highlighted: it is the focal pitch of the raga, sometimes known as ‘the note that speaks’ (vādī). On hearing these phrases alone, even with no announcement of the raga, connoisseurs might say to themselves: ‘Ah – Bihag!’

Alap is not in principle pre-composed (alap in the same raga can be played longer or shorter, depending on the time available). In these two short phrases one can see how Buddhadev Dasgupta interprets the well-known raga. A different musician might play the same underlying phrases with a different rhythm and different ornamentations. No one ‘composed’ raga Bihag, and there is no definitive written representation of it; it seems to have originated in the seventeenth century, and is still evolving – the prominence of F# has gradually increased over the past fifty years. Bihag is part of a canonical repertoire, but it is a canon of orally-transmitted, evolving practice rather than of written ‘works’.

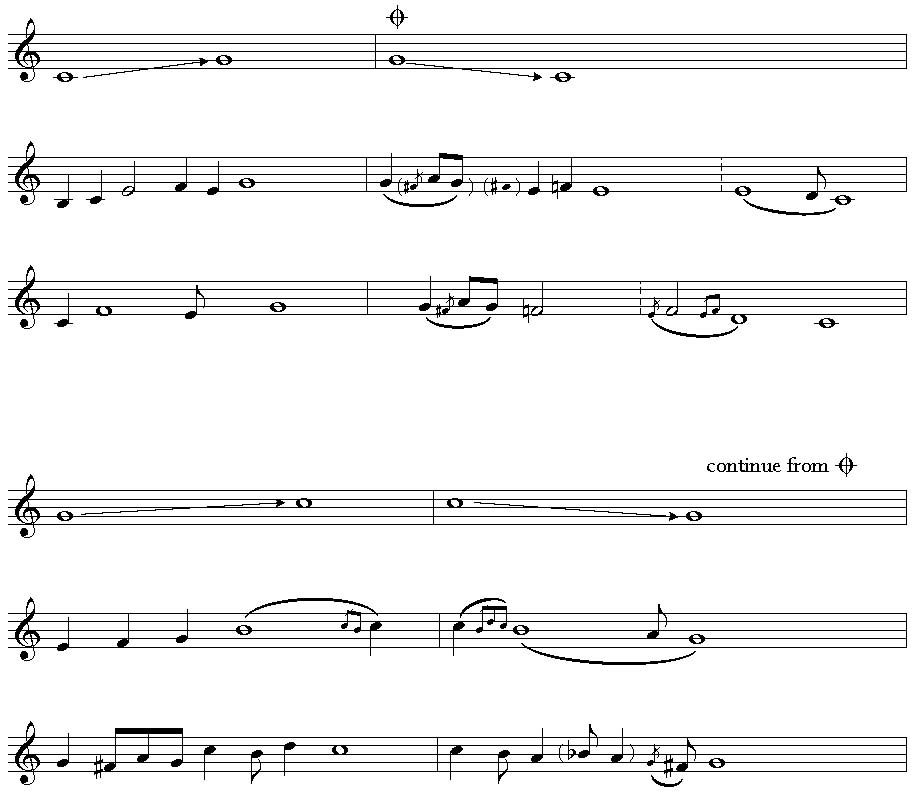

Hindustani musicians commit to memory large numbers of vocal or instrumental compositions. Most of them could be performed, in the form in which they have been memorised, in under two minutes. Each one will be ‘in’ a particular raga: there can be any number of compositions in the same raga, and they will all exhibit the features of the raga, in different ways. Example 6.3 is the instrumental composition or gat that Buddhadev Dasgupta plays after the alap in Example 6.2 (with slight rhythmic variations on the repeats). The same melodic phrases that we heard in the alap recur here in a different rhythmic style, and within Tīntāl, the most common tala – or cyclic metrical framework – in Hindustani music. This comprises measures or cycles of sixteen beats, each cycle divided into four groups of four-beat segments (shown by the dotted bar-lines in Example 6.3). The first beat of the cycle (marked x) is the most emphasised. Once it has begun, the tala can gradually increase in speed, but it cannot otherwise change in structure. The gat is accompanied by tabla.

EX. 6.2 The beginning of an alap in raga Bihag, played by Buddhadev Dasgupta (sarod)

The term gat implies rhythmic movement or gait, and this one has a lively, almost jerky rhythm, with a note on almost every beat, frequent subdivisions of the beat and syncopations: these are typical of fast compositions. But the first phrase, which comes back as a refrain after the other phrases, leads to an unexpected long held note at beat nine – the vādī, E – followed by a quietly played F before the rhythm picks up again at beat fifteen; the performers momentarily seem to stop playing, though of course the tala continues in their minds throughout. This charming rhythmic surprise is typical of the subtle idiosyncrasies for which compositions are treasured by musicians and connoisseurs.

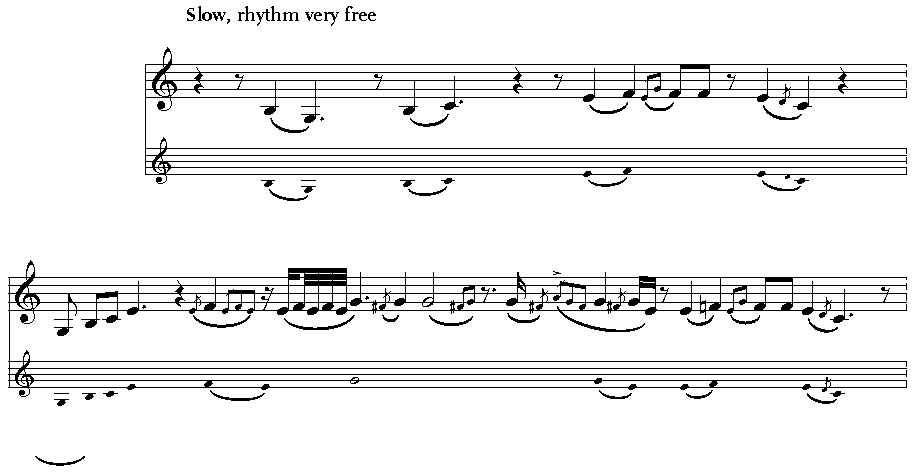

A composition of this kind is just the starting-point for improvisation using the melodic phrases of the raga and the rhythmic framework of the tala. Example 6.4 shows part of Buddhadev Dasgupta’s performance. A novice would have to learn passages like this, but a master would be able to invent them spontaneously. Notice how the improvised rhythm cuts across the framework of the tala, until the return to the composition at the end. The melody follows the phrases of the raga with some slight variations, and repeatedly hints at the beginning of the composition. The essence of this style of improvisation is the combination of changing rhythmic groupings and unexpected twists and turns of the melody, all at a fast speed that keeps the listener from guessing what will happen next.

Although each raga is said to have its own unique mood, this is hard to characterise because the mood can be varied by the performer, either by emphasising different notes and phrases at different times, or by changing the rhythm and tempo (always in the direction from slow to fast). In Example 6.2, the slow tempo and free-floating rhythm enable Dasgupta to bring out a feeling of profound calm while dwelling on the major third, and sliding slowly between it and the similarly peaceful fifth and tonic. Curvaceous movements bringing in other notes more fleetingly introduce a sensuous element, suggesting perhaps a mood of intense love enjoyed or recollected in tranquillity. Later in this short alap, however, as the pitch and intensity rise, the seventh (B) takes on a yearning quality as it seemingly strives to reach the upper tonic (C), yet only touches it momentarily before subsiding poignantly into the more tranquil regions below (compare the fifth line of Example 6.1). This combination of moods changes abruptly, with the introduction of the fast tempo composition (Example 6.3) and ensuing improvisation (Example 6.4), to one of confidence, energy and exuberance, with occasional touches of tenderness (Example 6.3, line 1, semibreve E and minim F) almost jokingly thrown in for surprise effect. The whole performance is a miniature, barely four minutes altogether, yet in terms of Indian aesthetics it seems to elicit flavours (rasa) of love, tranquillity and compassion in the alap, and manly vigour, surprise and humour in the gat; of the traditional nine aesthetic flavours, only fear, anger and disgust are avoided here (and would indeed be out of place in this raga). One is reminded of the philosopher Abhinavagupta’s comparison (c. 1000 CE) of a work of art with a dish in which various different spices combine to impart a unique flavour; but the music theorist Nanyadeva (c. 1100) observed that the flavours of different ragas, like food, cannot be adequately described in words, and must be experienced for oneself.

EX. 6.3 A gat composition in raga Bihag, Tintal, played by Buddhadev Dasgupta

EX. 6.4 Improvisation in raga Bihag by Buddhadev Dasgupta, and reprise of the gat melody

▪ Invasions, empires, Independence

It is assumed by most musicians and listeners that Indian classical music has been transmitted from generation to generation of performers for hundreds, indeed thousands of years. The antiquity of the ‘classical’ Hindustani tradition, however, is currently in dispute. Cultural historians point out that the term ‘classical’ has no indigenous equivalent (the commonly heard shāstriya sangīt is a translation into Hindi of the English ‘classical music’). The idea of Indian classical music, they claim, arose in a colonial context as a response to the threat of Western cultural dominance; it was systematised, standardised and promulgated as a public art-form by musical theorists, reformers and educators of the early twentieth century, and was embraced by the nationalist political movement. Before the twentieth century, these historians claim, there was no ‘classical music’ in either North or South India; merely a variety of musical traditions performed in different places by different social groups with little cultural or social prestige, and no uniformity. On the basis of these miscellaneous materials, Indian classical music was ‘invented’ in modern times.

This ‘invention hypothesis’ is a salutary reminder that many musical changes did occur in the twentieth century, as South Asia emerged from its colonial experience into the modern world, and it captures important changes in the way Hindustani music has been perceived and represented. But the documented historical record shows that change in music is nothing new, although there have also been significant continuities over very long periods of time. Change is most obvious in the musical instruments, most of which have acquired their present forms since the eighteenth century (see Voices and instruments below), but it can also be seen in vocal styles and in the social background of musicians, as we shall see in this section and the next. But twentieth-century theorists were not the first to attempt to systematise Indian music in written texts. Systems of raga and tala have been repeatedly re-codified in Sanskrit theoretical treatises (shāstra) beginning with the Nātyashāstra (c. third or fourth century) and the Brihaddeshī (c. eighth or ninth century), attributed to the mythical sages Bharata and Matanga respectively. Such early texts relate to modern practice in the general sense of establishing the nature of the concepts and some basic technical vocabulary: for example, the Brihaddeshī is the first text to discuss the raga concept in terms that are still valid today. Repertoire and performance practice, on the other hand, continue to change from generation to generation.

Despite this common tradition of theory in writing, until the fifteenth century or even later there was no twofold division of Indian music into North and South, but rather a diversity of deshī sangīta, ‘local music’, differing from region to region and from one level of society to another, rather as the ‘invention hypothesis’ would predict. Two particular factors caused these performance traditions to coalesce into Hindustani (North Indian) and Karnatak (South Indian) traditions. One is language: the linguistic families of Dravidian languages in the South and Indo-Aryan in the North underlie the corresponding grouping together of vernacular song repertoires and their associated music. The other is the arrival of successive waves of invaders from Central Asia, beginning with the conquest of large parts of north-west India by Turkish generals in 1192–98, and culminating in the establishment of the Mughal Empire, by rulers of Mongol origin, in the sixteenth century. These invaders brought with them not only the Islamic religion, but also – despite the problematic status of music within orthodox Islam – new musical instruments, scales and modes, poetic and musical genres, languages and musicians. Their impact was felt mainly, though not exclusively, in the North.

The infusion of the indigenous musical culture (which was highly regarded by the new political elite) with these foreign elements was a gradual process. By the fifteenth century the court singers of Man Singh Tomar, Hindu ruler of Gwalior, were composing songs in a partly new, partly traditional form called dhrupad, in the local Hindi dialect, to praise the ruler, the beloved and the gods; but at the contemporaneous court of the Muslim ruler Hussein Shah Sharqi of Jaunpur, some 300 miles to the East, they were singing Sufi poetry in a locally developed style that later came to be known as khayāl. These and other musical strands met at the courts of the Mughal Emperors, from Akbar (ruled 1556–1605) to Mohammed Shah Rangile (1719–1748), who unified the whole of northern India under their rule, and achieved much the same for Hindustani music.

The court of Akbar, in Agra and nearby Fatehpur Sikri, boasted an extensive musical establishment, including Muslim instrumentalists from Central Asia and Hindu singers from Gwalior. The former played instruments including the long-necked, fretted lutes that would later be transformed into the modern sitar and tambura. The singers, reputed to be the finest of the age, and headed by the incomparable Tansen (c. 1531–c. 1620), sang dhrupad songs set in ragas and talas; these were performed in semi-choral style by two or more male singers, with accompaniment of the indigenous barrel-shaped drum pakhāvaj. The poetry was largely secular, and the style of performance was majestic and impressive, perhaps expressing the grandeur and power of the Mughal regime. Each song would be prefaced by ālāp, a wordless, free-tempo, solo improvisation on the raga of the song. Dhrupad thus became the basic model for the performance of a raga in Hindustani music.

In 1648 Akbar’s grandson, the emperor Shahjahan, moved the Mughal capital from Agra to Delhi, where local musicians introduced to his court the songs of Amir Khusrau (a local Sufi poet of the thirteenth century) and Hussein Shah Sharqi of Jaunpur. Known as khayāl (‘fantasy, imagination’), and devoid of the abstract raga-development of alap, this style of singing was noted for its emotional intensity (dard). Dhrupad and khayal continued to develop and influence each other under the emperor Aurangzeb (1658–1707), who, contrary to popular myth, was a generous patron of music (in later life he refrained from listening to music out of religious piety, but he did not prevent others from doing so). It is perhaps not too fanciful to compare dhrupad with the massive grandeur of a Hindu temple colonnade, and khayal with the florid delicacy of a Mughal cusped arch; at all events, these two vocal styles, as developed at the Mughal court, are the key to understanding the musical idiom and performance structures of Hindustani music today. Thus in the performance by Buddhadev Dasgupta discussed above (Examples 6.2–4), the sequence of alap and composition follows the dhrupad model, but the convolutions of the improvisation (Example 6.4) reflect the khayal style.

By the time of the last great Mughal, Mohammad Shah Rangile, the wealthy elite of Delhi had developed an insatiable appetite for khayal, which has remained the more popular style to this day. Dhrupad and alap, and indigenous accompanying instruments, continued to be preserved by a few descendants of Tansen (a contemporary account describes how their loud voices ‘overpowered the thunder and seemed to pierce the ceiling’); but by this time the sitar and tabla were starting to replace the bīn (described below) and pakhāvaj as more suitable instruments for the khayal style. Of the female khayal singer Kamal Bai it was said: ‘Her melancholic voice is so melodious that it enraptures the hearts of the people… She can sing like a nightingale all night long and still retain the freshness of her voice’.3

A devastating attack by the Persian emperor Nadir Shah in 1739 inflicted a blow on Delhi’s musical culture from which it would never fully recover, and the later eighteenth and nineteenth centuries saw the consequent rise of provincial centres of music, including Lucknow, Gwalior, Agra, Banaras, Patiala, Rampur and the Rajasthani courts of Jaipur and Udaipur. As the Mughal Empire contracted to the region of Delhi itself, British colonial rule (based in Calcutta) correspondingly expanded, and by relieving local rulers of their political independence and responsibilities, enabled the more cultured rulers to maintain expansive musical establishments in the declining decades of their influence. These provided the leading musicians and dancers of the day (many of them from the waning Delhi court) with the opportunity to develop vocal and instrumental styles to unprecedented heights of virtuosity and sophistication. Typical of this period is the emergence of .tappā, an exceptionally florid style of song, originating in the Panjab and developed into an art form by Miyan Shori of Lucknow; and .thumrī, a delicate and sentimental song-style associated with Lucknow’s courtesan singer-dancers. These styles are considered ‘semi-classical’, because they do not present ragas in a systematic manner. By contrast, khayal singers, sitarists and sarodists developed their own styles of alap, thereby ensuring the ‘classical’ status of their art; the alap of dhrupad singers thus became an essential model for the development of other vocal and instrumental styles.

The later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were a period of major disruptions and changes in Hindustani music. The tragic events of the 1857–58 ‘Mutiny’, in which Indian and British communities attacked each other with unprecedented violence, spelled the end of the Mughal Empire and the establishment of the British; during this time many musicians were displaced from court to court in search of secure patronage. But the subsequent growth of the railways gave musicians the opportunity to establish reputations beyond the confines of their patrons’ palaces.

The legendary sixteenth-century composer and singer Tansen dominated music at the court of Akbar. He is depicted in this eighteenth-century Rajasthani miniature receiving a lesson from the composer Swami Haridas, while the emperor looks on.

Meanwhile, in the colonial cities of Calcutta and Bombay, the educated middle classes took up the cause of music with reforming zeal. As part of the ancient cultural heritage of India, music was too precious to be left to the increasingly discredited and impoverished princes and their court musicians: it had to be brought into the public life of a rejuvenated, modern and ultimately independent India. The efforts of Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande, Vishnu Digambar Paluskar and other reformers transformed the status and perception of Hindustani music, by reforming theoretical systems, establishing public teaching institutions, creating textbooks and promoting public concerts. Every city of northern India now has at least one music college at which members of the public – especially, for social reasons, young women – enrol in sitar or singing classes. Such colleges use printed textbooks explaining the theory of Indian music with exercises and compositions in music notation; early experiments with staff notation having been abandoned, the notation system used is an adaptation of traditional Indian solfège (sargam). The college teaching system does not produce professional performing artists, who invariably train with a guru or ustad, but it educates a significant popular audience for Hindustani music, who can hear public concerts by local artists or visiting stars for a modest ticket price (Paluskar had inaugurated this practice when he gave one of the first public, ticketed concerts in Gwalior in 1897). Such public events are held today in concert halls and theatres, or in large festival marquees set up near a temple or on the banks of a sacred river. Smaller concerts in private homes remain the quintessential context for music listening, however, and are usually by invitation.

Those musicians fortunate enough to have inherited court positions were initially reluctant to participate in the reform movement, which was largely aimed at taking music out of their control. But as their princely employers lost their budgets, or expended them on lavish lifestyles in Paris or New York, musicians needed to find new patrons. Gradually they embraced the new technology of gramophone recording, introduced in 1902, which allowed those wealthy enough to own a record player to hear the greatest musicians in their own homes. Broadcasting, which began in India in 1927, also became an important source of income for musicians; a system of graded artists was established, with ‘staff artists’ permanently on station to accompany the A-grade soloists for their live broadcasts. For many years, classical music was protected by All India Radio from competition from popular film music, but it is now increasingly a niche market for radio and television. Until the 1970s EMI/HMV India held a virtual monopoly of the record industry in India, and published a limited selection of 78 and 33.3 rpm records of classical artists, many of which are still treasured as classic recordings by connoisseurs today. The arrival of cassettes in the 1970s and CDs in the 1990s, however, opened the market to many other companies and allowed a wider diversity of genres and artists to be heard. This diversification has also allowed a ‘grey market’ in previously unpublished archive recordings to develop, bringing back to older listeners their favourite performers of the 1950s and 1960s (such as Amir Khan or Bade Ghulam Ali Khan), who, though fêted as innovators in their day, now seem to evoke the musical values of pre-modern India.

Outside India, a post-colonial world has embraced the idea of Indian classical music with considerable enthusiasm. Starting with the tours abroad of Ravi Shankar and Vilayat Khan in the 1950s, a variety of instrumentalists, and a few vocalists, have achieved fame and fortune in Europe, North America, Australia, Japan, Israel and elsewhere. This helped to enhance their status in India too, as representatives of Indian culture and of the newly modern Indian nation, to the outside world. This role has been largely supplanted by film music, which is now heard almost everywhere, and is seen more readily as a musical emblem of modern India; but there are still frequent tours by classical musicians, festivals of Indian classical music, and courses of instruction in many parts of the world. Indian musicians resident and teaching abroad (for example, the late Ali Akbar Khan in California) have helped non-Indian musicians to learn the art themselves, and thereby have established a global community of performers and connoisseurs.

▪ Voices and instruments

It would be hard to overstate the importance of the voice in Indian culture. In Hinduism, the chanting of Vedic scriptures in ritual was believed in ancient times to sustain the universe; this belief led to the development of the science of phonetics, which also influenced music theory. In Islam, rhythmic chanting of the name of Allah, zikr, is prized by Sufi devotees as an ecstatic form of communion with the Divine, and this too has echoes in classical music. Most popular religious traditions in India use sung poetry in various regional languages as an expression of devotion to the chosen deity, and songs of this kind are also found in the classical music repertoire, alongside more secular ones.

Theory books have much to say about the virtues and faults of singers, but there is no one method of voice training for classical music; each teacher will have his or her own methods, tailored to the individual pupil. Voice production not only varies between the three principal vocal styles described below, but has also changed across the stylistic spectrum during the twentieth century. A beautiful natural tone is not especially prized, and older singers prioritised loudness over tone quality, both to express intensity of feeling, and in order to be heard in the larger spaces of the palace or temple over the sound of loud accompaniment (especially the drum pakhāvaj); singers often sang in small groups to achieve even greater resonance for the pre-composed parts of a performance, as still happens in temple music. The advent of the microphone, essential for performances in marquees and now used everywhere, has enabled classical singers to sing more quietly and with more subtlety of tone and ornamentation; quiet instruments need no longer struggle to be heard and more subtle effects can be exploited (provided the sound system is adequate).

The main requirements of the classical singer include:

mīnd: the flexibility to glide smoothly from one pitch to the next

ās: resonance – a strong tone throughout the range (usually three octaves)

shruti: precise intonation

gamak: ornamentation

These and other criteria combine to form the ‘vocal style’ (gāyakī) of the singer, which is partly unique to him or her, and partly inherited from the ‘household’ (gharānā) or lineage of teachers and disciples he/she belongs to.

Vocal style also correlates to some extent with historical genres, repertoires and social communities of performers. Three distinct vocal genres are recognised, dhrupad, khayal and thumri, whose historical origins are traced above. Hereditary male solo singers who can trace their ancestry to the Mughal court are called kalāvants and their special preserve is dhrupad; few such families now survive, but many musicians claim to have inherited the tradition of Tansen’s descendants through their teachers. Hereditary female singers sing thumri and trace their origins to the courtesan communities that graced the courts of Lucknow, Banaras (Varanasi) and Delhi in the nineteenth century. Again, few such lineages survive, because of the rejection of the courtesan profession by the ‘respectable’ urban middle classes in the early twentieth century. Khayal singers have probably always included a mixture of professional and non-professional, hereditary and non-hereditary, male and female, Muslim and Hindu musicians. Today they include singers originally from the Mirasi community, a Muslim caste of hereditary folk musicians from the Panjab, who moved into the urban centres as accompanists of courtesans in the nineteenth century, playing tabla and the bowed lute sārangī; by re-training as khayal singers they came to dominate classical music in the twentieth century. All these social categories of musician have been largely supplanted in the later twentieth century by non-hereditary Hindu musicians from high caste, urban, educated middle-class backgrounds. While these include both male and female musicians, women still avoid playing tabla and sārangī because of their former association with the courtesans and their male accompanists.

Instruments and instrumental music can be discussed alongside the three vocal genres because they have evolved to emulate vocal style; melody instruments, at least, are effectively surrogate voices. Instrumentalists often take training from a vocalist and it is a compliment to an instrumentalist to say that one can hear the voice in their instrument.

The dhrupad vocal style is considered to be very plain, almost unornamented apart from smooth glissandos and slow oscillations. Performance begins with a long, slow alap, followed by a song which can be slow or fast. Performers usually bring their performance to a vigorous climax by improvising on the words of the song in lively rhythmic competition with their accompanist, who plays the majestic barrel-shaped drum pakhāvaj rather than the lighter-toned tabla. Although it was a secular art-form at the Mughal court, performed in praise of the monarch, dhrupad is now considered a religious or spiritual act of devotion, with words in praise of Hindu deities or Allah, or on philosophical subjects including music theory. Dhrupad singers are considered to be experts in raga, tala and intonation (shruti).

The instrument traditionally played in dhrupad style is the bīn or rudra vīnā. It comprises a hollow tube of wood onto which are mounted four melody strings, frets, bridge and three drone strings. Behind the tube, which is held vertically or horizontally in front of the player, hang two very large gourd resonators; nevertheless the sound of the instrument is very quiet. The size of the instrument and its exceptionally deep pitch make it unsuitable for rapid playing, but it is ideal for alap in the dhrupad style. Two features of the instrument are especially important for cultivating a vocal style: the bridge is carefully shaped to induce a slight buzz, which gives the sound resonance and duration; and the strings can be pulled at the fret to produce a smooth glissando or oscillation. Unfortunately today there are no more than a handful of players of this instrument, which used to be cultivated especially by the kalavant descendants of Tansen’s daughter Sarasvati (the last of whom, Ustad Dabir Khan, died in the 1960s).

In contrast to dhrupad, khayal style is very florid, employing a wide range of ornamental and virtuoso techniques, most of which are strictly forbidden in dhrupad. Accompaniment is on the tabla. Performance usually begins with a composed song rather than the long alap of dhrupad, and ends with bravura tāns – rapid and convoluted arabesques sung to the vowel ā – which are unique to the khayal style. Between the song and the tans the singer may develop the raga in a leisurely ‘expansion’ (vistār, barhat); this is similar to alap but is accompanied by the tabla throughout, and periodically the singer will remind us of the song by repeating its first phrase. If the speed of the tala is slow (tempi of five seconds per beat or slower became common in the later twentieth century), the performance usually ends with a second, fast-tempo composition in the same raga, ending with further tans. Slow-tempo expansion of the raga is believed to have been introduced to khayal in the mid-twentieth century in emulation of the slow alap of dhrupad.

Khayal singers, male and female, usually also sing the thumri style – often for the last item of a concert – though there are also specialist thumri singers. The emphasis here is on the delicate interpretation of the words, which are flirtatiously or poignantly addressed by a female to her lover, typically imagined as being either absent and longed for, or present and mischievous. If the lover is addressed as Krishna, it is to evoke well-known stories of his youthful amorous frolics with the milkmaids of Braj (the Indian Arcadia) rather than his religious status as an avatār of the great god Vishnu. Only the ‘light’ ragas are used – those that have a playful or melancholy mood, and folksong-like charm – and in place of the abstract melodic development of alap or the bravura flourishes of khayal, the singer improvises around the words, with delicate ornamentation, extracting every ounce of emotional meaning, even if that means occasionally going beyond the melodic boundaries of the raga.

Most melodic instruments today are played in khayal style, often blended with elements of dhrupad and/or thumri; it is the flourishes of khayal that give most scope for the astonishing instrumental virtuosity that has been perhaps the most remarkable development of Hindustani music in the post-colonial age. The best known of all Indian instruments, the sitar, only reached its pre-eminence in the mid-twentieth century, in the hands of internationally famous players such as Vilayat Khan and Ravi Shankar; it is played today by musicians of both genders and almost any social background, including a number of non-Indian players. Its development began with much smaller, delicate, long-necked lutes played at the Mughal court, similar to the setār of Persian music. Its transformation over three centuries into the modern instrument involved making the neck broader to allow more pulling of the string at the fret, transferring to it the buzzing bridge, gourd resonators and high frets of the bin, and cultivation of a lyrical, vocal style that combines elements of dhrupad alap and khayal ornamentation. Even closer in sound to the bin is the bass sitar or surbahār, invented in the nineteenth century, which is used mainly for alap. Both the sitar and the surbahar normally have a bank of sympathetic strings that add lustre to the sound by resonating in sympathy with the notes played on the melody strings. Originating from the same Central Asian lutes, the tambūrā or tānpurā has evolved into a large, fretless instrument of exceptional resonance, the open strings of which provide the ethereal background drone to a vocal or instrumental performance. Playing tambura is a traditional role for disciples or female relatives of the soloist.

A sarangi bowed lute

When the infant Krishna played his flute, the cow-girls flocked to his side: a fresco on an interior wall of City Palace, Udaipur.

Descended from the Afghan rabob lute, the sarod has been so effectively championed by players including Amjad Ali Khan (top left) that as a solo instrument it now rivals the sitar, played here by Anoushka and Ravi Shankar (bottom right), and seen (bottom left) in an eighteenth century Rajasthani miniature. Mastery of the rudra vina, or bin, played here by Asad Ali Khan (top right), is these days confined to a small handful of musicians – despite its being ideally suited to the dhrupad style.

The nineteenth century was an era of rapid development in the design of classical instruments, and Indian museums are stocked with innumerable, sometimes bizarre, experiments in enlarging traditional instruments or combining Indian and Western instruments. Apart from the surbahar most of these failed to catch on, but an important success story is that of the sarod. In the early nineteenth century, Pathan settlers in the area of Rohilkhand were playing the Afghan rabob, a short-necked lute with a narrow-waisted resonator that is deeper than it is wide, four gut melody strings and many steel sympathetic strings. Despite the latter, the sound of the melody notes was of short duration, and the four gut frets on the neck made it difficult to emulate the smooth glides of dhrupad or the rapid ornaments of khayal. By removing the frets, bolting a polished steel plate to the fingerboard and enlarging the bowl of the resonator, Indian musicians, including several from Tansen’s family, transformed the rabob into a more resonant instrument, on which glissandos could be played by sliding the stopping finger along the string. On this new instrument, the sarod, they could reproduce aspects of thumri, khayal and even dhrupad styles; today the sarod rivals the sitar as one of the main vehicles for Hindustani instrumental music. Musicians of Afghan descent such as Amjad Ali Khan, or of Tansen’s discipular lineage such as the late Ali Akbar Khan and Buddhadev Dasgupta, have been prominent among players of the modern sarod.

Like the sitar and the sarod, the sārangī has Central Asian ancestry and can be traced to the Mughal period or even earlier. It is a bowed lute, box-shaped with incurved sides, carved from a single block of wood; like the rabob and sarod, it has a skin table and many sympathetic strings. Because the bowing technique and sympathetic strings give resonance, while the fingers can slide freely along the string, it is not only played in vocal style, but is regarded as the ideal accompaniment to the voice; its melancholy solo sound is also associated with funeral occasions and replaces other music on the radio when a national leader dies. It is largely played by male hereditary musicians of Mirasi or similar background. Because of its former association with courtesan culture the instrument and its players are marginalised in India, and there are concerns for its survival. In the twentieth century, however, the virtuoso player Ram Narayan, and recently his daughter Aruna, have earned greater respect for the sarangi as a solo instrument.

Though not a melodic instrument, and traditionally an accompanying rather than solo instrument, the tabla has achieved enormous popularity within and outside India, owing to the virtuosity of its players and the remarkable range of sonorities and rhythmic effects they can produce. It is a pair of small drums, played with the hands; one drum is tuned to the tonic pitch of the raga chosen by the soloist, the other to a deeper pitch which can be modulated by varying the pressure of the hand while striking. This modulation gives a vocal character to the sound, and in fact all the sounds of the instrument are encoded in a syllabic ‘notation’; vocal recitation of the syllables (bol) at high speed is an essential skill for tabla players. The players are almost invariably male, like sarangi players, and traditionally came from the same families; now players come from a wide range of backgrounds and a small number of women players are emerging.

While the above instruments constitute the most ‘traditional’ instruments of Hindustani music, instruments from outside the classical tradition can also be used, provided their technique and construction allow the Hindustani vocal styles to be rendered on them. The oboe shahnāī (‘royal flute’) is played mainly in outdoor settings for temples and weddings, but was brought into concert music by the late Bismillah Khan. The bamboo flute bānsurī, traditionally played by the same families of temple musicians as the shahnai, was revived by the late Pannalal Ghosh in an enlarged, deeper form on which alap and khayal could be played, as they are today by Hariprasad Chaurasia and others. Instruments of Western origin include the harmonium, a small portable reed organ that since the nineteenth century has increasingly replaced the sarangi as an accompaniment to the voice; the violin, used mainly as a solo instrument; and the guitar, modified for playing in Hindustani style by Vishwamohan Bhatt and others. The santūr, a box zither with steel strings played with delicate finger-held beaters, is of ancient Middle Eastern origin, but was introduced to Hindustani film and classical music by its supreme exponent today, Shivkumar Sharma. Although the sound is attractive to many listeners, it is impossible to produce a true glissando on the santur. As if to compensate for this limitation, some proponents of the santur make exaggerated claims for its antiquity in India. The re-invention of Indian classical music, and of its history, continues as it has always done.

Further reading

Perhaps the best starting point for an exploration of Hindustani music is Joep Bor’s The Raga Guide, which helpfully combines discussion, notated examples and audio tracks on CD, not to mention examples of rāgamālā paintings with their inscriptions translated, and a glossary. More analytical approaches to the subject of rāga can be found in Nazir Jairazbhoy’s The Rāgs of North Indian Music (1971), and in the articles ‘India, subcontinent of’ and ‘Mode’ in the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. James Kippen’s chapter in The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music vol. 5, South Asia, is an excellent introduction to the Hindustani tala system, and more detail is to be found in Martin Clayton’s Time in Indian Music. Neil Sorrell and Ram Narayan’s Indian Music in Performance and George Ruckert’s Music in North India combine discussion of performance and structure in Hindustani music with aspects of the cultural context and the performers themselves; more detail on the latter will be found in Daniel Neuman’s anthropological study The Life of Music in North India (1980). The musical characteristics, cultural contexts and historical evolution of the vocal styles dhrupad, khayal and thumri are traced in Ritwik Sanyal and Richard Widdess’s Dhrupad, Bonnie Wade’s Khyāl and Peter Manuel’s Thumri in Historical and Stylistic Perspective respectively; for instrumental music, studies by Allyn Miner (Sitar and Sarod in the 18th and 19th Centuries), Adrian McNeil (Inventing the Sarod) and James Kippen (The Tabla of Lucknow) have illuminated the development and social history of the sitar, sarod and tabla respectively. The history of Hindustani music in its formative centuries (thirteenth to twentieth) is spectacularly illustrated in Joep Bor and Philippe Bruguière’s Gloire des princes, louange des dieux, and authoritatively surveyed in Bor, Françoise Delvoye, Jane Harvey and Emmie te Nijenhuis’s Hindustani Music. Musical systems and speculations of the preceding era are lucidly documented in Lewis Rowell’s Music and Musical Thought in Early India, while the history of the West’s encounter with Hindustani music is traced in Gerry Farrell’s Indian Music and the West. Donna Marie Wulff’s chapter ‘On practicing music religiously’ in Joyce Irwin’s book Sacred Sound is a judicious assessment of the relationship between classical music and the spiritual traditions of North India.

Recommended listening

Numerous 78 rpm and LP recordings of great twentieth-century Hindustani vocalists and instrumentalists are considered classics by Indian musicians and music-lovers, and are now available through online services such as iTunes, or in dedicated Indian music websites such as the ITC Sangeet Research Academy (http://www.itcsra.org/). The following is a small sample of historic and contemporary recordings.

The Raga Guide (4 CDs with book), Nimbus NI 5536/9, 1999. Each of seventy-four ragas, including all the most important ones, is illustrated on CD by a five-minute miniature vocal or instrumental (flute or sarod) performance, in which a composition and improvised raga-development are both briefly encompassed. Examples 6.2–4 in this chapter are based on a track from this collection. The accompanying book includes commentary, transcribed excerpts and song texts and translations.

Uday Bhawalkar, A dhrupad recital, Navras Records NRCD 0058, 1996. A contemporary rendering of the dhrupad vocal style, but very true to tradition.

Zia Mohiuddin Dagar, Rag Yaman and Suddh Todi (2 CDs), Nimbus Records NI 7047/8, 1991) Perfection of dhrupad-style alap performance on the rudra vina (bin).

Amir Khan, HMV EALP 1253 (LP). Available from Saregama through iTunes as Amir Khan – Marwa and Darbari. Two definitive raga performances in khayal style, by the singer that many Hindustani musicians most admire.

Living Music from the Past: Kesarbai Kerkar, Underscore Records 04AM011, 2004. Available in iTunes. A compilation of 78 rpm recordings from 1935–8 by one of the first female khayal singers to win popular acclaim in North India. One of her tracks (not in this compilation) was included in a sampler CD carried on the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft. Here the final track is an example of thumri style.

Pandit Rajan and Sajan Mishra, Navras Records NRCD 0057, 1996. A characteristic performance by two of the most popular khayal singers today.

Ustad Vilayat Khan, Raga Yaman, HMV ASD 2425 (LP), 1968. Available from Saregama through iTunes as Evergreen Yaman. Extended rendition of this major raga in khayal style by the most admired sitarist of the twentieth century.

Ravi Shankar, Sound of the Sitar, World Pacific (LP), 1965. Available from Angel Records through iTunes as The Ravi Shankar Collection: Sound of the Sitar. The world-renowned sitarist at his peak, in an extended alap (raga Malkauns) showing the influence of dhrupad style on sitar.

Amjad Ali Khan, Atma, Audiorec Classics ACCD 1004, 1990. Illustrates contemporary sarod style as played by a leading exponent of Afghan descent, and includes a full-length performance of raga Bihag (cf Examples 6.2–4 in this chapter).