A Bektashi djem in Anatolia: a ritual of one of Turkey’s ecstatic religious orders

Buoyed by dinner and many glasses of spirits, the guests settle in the living room with sweets, and some open instrument cases. Laughter and the tinkle of metal spoons on tea glasses mingle with the sound of a long-necked lute being tuned. A young woman tries out her zither, while an older man blows tentative tones on his flute. Another young woman balances a short-necked fiddle on her knee: it’s tear-drop shaped, and its voice is surprisingly large; a percussionist inspects his frame drum with brass jingles. Now the sound of the flute, breathy and full of overtones, cuts through the talk, its melody moving meditatively upward in free rhythm as the other players provide quiet drones; the fiddle and lute step in, and the three converse together, conclude together. Then instruments and drum begin to move as one, in a piece in a stately tempo. After the final refrain, a guest begins to sing, freely at first, then joined by instruments. Another song follows, then others, the tempo increasing as the listeners sip tea, comment or sing along; a phone rings unanswered. Suddenly the instruments are hushed, playing a steady ostinato as a singer, eyes closed and head to one side, enters high. He begins with sustained notes, then recites on a few pitches with dramatic pauses, trilling and bending the notes with occasional rapid passages. The intense feeling resolves in a final song in quick tempo, with applause at the end, interrupted by a fast postlude. More tea is poured, and the music is submerged once more in conversation.

TURKS use a term adapted from the West, klasik Türk müziği1 (‘classical Turkish music’), as a catch-all for the musical practices and repertoires of the Ottoman Turkish upper classes over six centuries which continue to the present day. An alternate form, Türk sanat müziği (‘Turkish art music’), is also a Western adaptation. Like ‘classical’ and ‘art’ as used in Europe and North America, the terms are intended in part to convey a sense of high status and cultural depth. This chapter will avoid such distracting associations by substituting a different term: Turkish makam music. ‘Makam’ is a word the Turks inherited from the Arabs (maqam), so by using it to describe this music we are instantly linking it to its regional heritage. In Arabic and Ottoman music-theory writings since the thirteenth century, maqam/makam carries the meaning of ‘melodic mode’, in the same general sense in which we refer to the melodic modes of medieval Europe and the ragas of India. Thus makam also helps to place Ottoman music globally, as one of the world’s melody-centred, or monophonic, traditions.

In 1923 the Ottoman Turkish dynasty – founded in the fourteenth century, and for much of its span the self-appointed guardian of Muslim civilisation in the Mediterranean – was replaced by a resolutely secular Turkish republic. In the eight decades since the end of Ottoman rule, Turkish makam has created a place for certain pre-twentieth-century Ottoman musical sensibilities in the ever-expanding range of repertoires in Turkey’s musical life. As with Western classical music, Turkish makam enters cultural life through public concerts, radio and television, recordings and the internet, but only since 1974 has it been taught in state-supported conservatories.

To most modern Turks this music, like Western classical music to Europeans and Americans, carries with it suggestions of the past, of nostalgia for pre-modern life, and a sense that it is an elite music for the few. But it continues to evolve in the hands of new generations of musicians, bringing a special seriousness, virtuosity and invention to a Turkish niche audience.

Back in the 1980s I performed an audio experiment which illustrates the niche in which this klasik set of practices and repertoires now fits. Late one afternoon, as I got off the ferry at Kadıköy on the Asian side of the Bosphorus, I turned on my cassette recorder and began to walk, taking in all the sounds of the street. Through the open windows of the practice rooms at the Kadıköy branch of the Istanbul conservatory came the sounds of teenage pianists practicing Bach two-part inventions and boogie woogie bass lines. Next to the quay a nineteenth-century mosque, too small to afford a full-time müezzin, broadcast a recording of the afternoon call to prayer from its single minaret. Scratches on the record punctuated the same Arabic words being heard at that moment, mostly delivered by a live muezzin, from the minarets of each of the city’s more than two thousand mosques (but here no one prayed, or even stopped). The music shops and cafés on the cobbled streets going up the hill had speaker systems too: American, British and Turkish jazz and rock, Turkish pop mixing Turkish instruments, guitars and synthesisers and Turkish folk music including that of the traditional Anatolian troubadour (aşık) whose poetry is saturated with references to mystical Islam. A restaurant with white tablecloths added a bit of Verdi to the mix. In this short walk, my tape had captured a fair sampling of contemporary Turkish musical life. The main element missing from this array was the repertoire which is the subject of this chapter.

There are reasons for its absence, and the performance described at the opening of this chapter suggests some of them. As flies on the wall of that fictionalised middle-class living room, we could observe that this music arose naturally out of informal conversation: in this intimate setting the voice is central and the words of the older songs (mostly in a language no longer spoken, which mixes Turkish with Persian and Arabic) reflect the centuries-old association of Turkish makam with Islamic mysticism, in which the unattainable love-object is often ambiguously mortal and divine. The ensemble is small and transparent, allowing every musician to be heard. Etiquette governs the musical texture of the performance, as in polite society – lütfen buyurunuz (‘please, after you’): your turn, now my turn, now together. A single melody attracts the listener’s attention, yet the texture is complex, spontaneous and multi-voiced, with one instrument of each type speaking as a soloist. The result is like the conversation from which the performance emerged, where each voice can be heard and appreciated.

In certain ways we could have been flies on the wall in an aristocratic mansion or Ottoman palace in the eighteenth century. Women were then often prominent performers as well, though usually as family members, servants or members of the harem. Before the twentieth century, in a society shaped more profoundly by religion, this music was dominated by members of Sufi tarikats, the mystical Islamic brotherhoods outlawed by the new Republic in the 1920s; in recent decades these have been returning to public life. The instruments in this performance are versions of those in the eighteenth century, as is much of the musical terminology; even some of the repertoire is by musicians born in that time.

No wonder such a sensitive multi-century concoction is so rarely heard on the street (but then, how often is a Haydn string quartet heard on the street either?). No wonder attempts continue to be made by musicians, abetted by government arts policy since the 1920s, to fatten this intimate conversational model with mixed choruses and large orchestras, to compete with the sheer heft of the Western symphony orchestra, the concert grand piano, the bel canto singing style and four-part harmony. For modern Turks have a full plate: virtually any music available to listeners in the United States and Europe is available to them. Many under the age of sixty heard more Mozart and Jimi Hendrix than Hamamizade Dede Efendi (1778–1846) as children. As comparison-shoppers they, like listeners of Western classical music, hear Turkish classical music as just one voice among many.

Therefore we must ask: what special qualities does Turkish makam music have that allow it to hold its place in a field which includes Turkish folk music, Turkish pop, Turkish jazz, Turkish symphonic music and Turkish film music? Part of the answer is not musical at all, since both the practice and the meaning of music (any music, Eastern or Western) arise from history. Long before we have heard the first note of Turkish classical music, we have been prepared for what to expect from it, and even for what it means. So before taking the plunge into the terrain of koma and vezin, peşrev and taksim, it is to history we must turn.

… infidels are not to mount a horse, wear a sable fur, fur caps, European silk, velvet and satin. Infidel women are not to go about in the Muslim style and manner of dress and wear Paris overcoats …

From a royal decree by Sultan Murad IV in 16312

It may be confirmed for a proper truth that, if the western princes had been lords of Asia, instead of the Saracens and Turks, there would be now no remnant of the Greek church, and they would not have tolerated Mahometanism, as these Infidels have tolerated Christianity…

Entry on ‘Mahomet’ in the 1697 Dictionnaire historique et critique

by French Protestant philosopher Pierre Bayle3

As is suggested by these two seventeenth-century sources, one Turkish and the other European, the history of the Ottomans is no simple matter to summarise, especially when viewed from both sides of its borders: six hundred years of dynastic rule by the house of Osman, preceded by seven hundred years of Arabic Muslim rule to which the Ottomans were heirs, and incorporating at one time or another all the peoples, religions, languages and lands from North Africa (excluding Morocco) to the border of present-day Iran, from the Persian Gulf to the Black Sea and much of the Balkans.

Two historical themes may help sharpen our understanding of Ottoman music and its twentieth-century continuation.

Until recent decades, European-language accounts of Ottoman-European relations have tended to emphasise conflict. But the historian Richard Goffman’s term ‘symbiosis’ suggests something more like a mutual dependency – by no means devoid of conflict, but also more interconnected. This is a view of politics and economics which prepares us to hear Ottoman music as former generations in the West never could. For them, Turkish music was inseparable from the conflict paradigm, the embodiment of inalterable otherness – Turkish barbarity, aggression and depravity in another form. But music is also promiscuous, carried in the air and in memory over boundaries of neighbourhood and ethnicity, making the idea of interaction and mutual dependence as good a place to begin our exploration of Ottoman history and music as the idea of continual conflict.

The Ottomans never wavered in their belief in the superiority of the Muslim message to mankind, viewing the non-Muslim peoples of their empire as second-class citizens – ‘separate, unequal and protected’, as one historian has put it5 – and charging them with a special tax. General Muslim practice designated monotheistic communities which chose not to convert to Islam ‘people of the book’ (ahl al-kitab) because of the obvious textual links between the Old and New Testaments and the Qur’an. But the Ottomans saw the ethnic and religious diversity of their domain as essential to the empire’s internal harmony and economic strength, and took extra steps to manage it. Greek, Armenian and Jewish communities, each an official Ottoman minority (millet), lived in their own neighbourhoods and towns, spoke their own languages, and lived by their own codes under their own religious leaders who answered to the Ottoman authorities.

The participation of Jews and Christians in Ottoman society (especially in its economic life) was vigorously protected when competition among groups threatened the status quo, even leading at times to the suppression of troublesome Muslim groups. As historian Cemal Kafadar has pointed out, Ottoman tolerance was less like modern tolerance and closer to the original Latin word – toleo, meaning ‘to bear’, as in ‘how much pain can you bear?’6 And until the rise of European-style nationalism in the nineteenth century, the Ottoman region could bear considerable diversity. This picture of a pragmatic cosmopolitanism provides a useful platform for approaching Ottoman makam music: a polyglot mix of Arabic, Persian, Greek, Jewish, Armenian and Turkish cultural inheritances, developed through a long history of direct and sustained interactions among distinct and stable communities.

In the year 1299 a regional Turkmen chieftain known as Osman separated from the confederacy of the Selçuk Turks which had spread from the East and taken much of Anatolia from the Byzantine empire over the preceding century, and became the first of the Osmanlı or Ottoman rulers. He was renamed Osman I by later generations to mark his place in a potent and growing dynastic line. In the fourteenth century that dynasty assumed the title sultan (Arabic: ‘supreme authority’), and eventually several other titles reflecting the empire’s cultural heritage: han or khan (Turkmen) and padişah and hünkar (Persian). By the time the sultanate was abolished as an institution by the newly created Turkish National Assembly in 1922, thirty-six Ottoman sultans had come and gone, with the last of them, Mehmed VI, ushered quietly into exile in Monte Carlo.

The Ottomans succeeded to a series of Muslim empires in the Middle East and North Africa which made capital cities first in Damascus and then in Baghdad. The highly Persianised Seljuk Turks, who planted the seeds of an enduring Persian legacy within Ottoman culture, made their capital in Konya, in central Anatolia. After the Seljuks, the Ottomans made capitals farther west in Bursa (1324), Edirne (1363) and finally Constantinople (1453). The spiritual centre of each of these Muslim empires remained the so-called Hicaz, the region incorporating the holy cities of Mecca and Medina on the Arabian peninsula. The succession of Islamic capitals from the eighth to the fifteenth centuries, however, shows a gradual shift from the Middle East (the Arabic kingdoms) to Anatolia and Europe (the Turks). From 1453 to 1923 the Ottoman centre at Constantinople/Istanbul physically straddled the Bosphorus, the waterway dividing the two parts of the Eurasian subcontinent. Inhabitants of modern Istanbul still speak of the eastern and western halves of their city as Asya (Asia) and Avrupa (Europe), as casually as Parisians refer to la rive gauche and la rive droite.

Yet it is no accident that the map of the Mediterranean Muslim empire at its height under the Ottoman sultan Süleyman I in the sixteenth century should so closely resemble that of the Christian Byzantine empire at its greatest extent in the sixth century under the emperor Justinian: both Justinian and Süleyman had their eyes fixed on an earlier benchmark. Before the Byzantines, the pagan Roman empire in the second century CE had reached from Britain to Persia, and Greek Christian rulers after Constantine the Great in the fourth century had been inspired to live up to the pagan model. Beginning in the seventh century, ambitious Arabic, Berber and Turkish Muslim rulers also aspired to adapt the Roman model, now Christian, to their own purposes. ‘Rome’ now had a second capital city in Constantinople on the Bosphorus, which Constantine had favoured over the city of Rome as the centre of gravity for Christianity. The conqueror of Constantinople, Sultan Mehmed II, referred to himself as Caesar of Rome, kayzer-i Rum. Today, the word Rum in Turkish commonly stands for ‘Greek’ (by extension Christian), since that is what the model of ‘Rome’ had meant to Middle Eastern Islam.

The extent and rapidity of the spread of Islam from China to Spain – including the fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans in 1453 – was not lost on rulers of Europe, instilling a sense that the Christian lands were beset by hostile non-Christian forces. Yet conflict and competition for land and souls in the Mediterranean world also had the effect of creating a mutually defining sense of identity on both sides. European maps of the world in the centuries after Columbus depicted an orbis christiani, the Christian regions (Europe) staked with crosses, bounded on the west by the Atlantic Ocean and to the east and south by regions – mostly Ottoman – flagged with the crescent of Islam. Parallel concepts to orbis christiani, inherited by the Ottomans from earlier Muslim theologians, divided the world starkly between dar al-Islam and dar al-harp, ‘the house of Islam’ and the ‘the house of struggle’, ameliorated only by dar al-suh, ‘the house of truce’. Moreover, internal conflicts – Muslim against Muslim and Christian against Christian – were the rule on both sides. But even though brisk commerce between the Muslim and Christian kingdoms rarely ceased, even in wartime, each side continued to pay lip service to the unity of their religious communities with concepts like umma (the community of Muslim believers) and Christendom. Each side defined the extent of its own community according to where the other community stopped, and each nurtured its own dream of a world united behind its particular revealed truth.

A band in Ottoman Aleppo, depicted by Alexander Russell in 1794 under the title ‘The Chamber Music drawn from Life’. As described by Russell, ‘the first is a Turk of lower class, he beats the Diff. The person next to him is an ordinary Christian and plays the Tanboor. The middle figure is a Dervish, he is playing the naie. The fourth is a Christian of middle rank, he plays the Kamangi. The last man, he beats the Nakara with his fingers in order to soften the sound for the voice, but the drum sticks appear from under his vest.’

As for oriental music, it has continued to stagnate. For, in preserving quarter tones, it has always been deprived of harmony. After it was translated into Arabic by Farabi, this unhealthy music found success at the court and was transmitted to the Persians and the Ottomans…

Ziya Gökalp, 19237

These words of Ziya Gökalp (1876–1924), an influential thinker during the transition period from Ottoman empire to Turkish republic, echo the more extreme sentiments of the generation of Turkish leaders who emerged during and after the First World War. Centuries of wariness of the non-believing civilisation to the west, followed by guarded curiosity about its workings – both attitudes compatible with an enduring Euro-Ottoman symbiosis – was replaced within a few decades by the one-sided conviction that much of the ‘oriental’ culture of the Ottomans now stood in the way of progress. Practices of law, finance, education and industry were openly borrowed from the same nations which, as victors over the Axis Powers (Austria-Hungary plus the Ottomans), had just dictated the terms of the Treaty of Sèvres (1920) which partitioned the multicultural Ottoman empire into separate national entities. In the view of President Mustafa Kemal Atatürk (1881–1938) and his ministers, the demise of the Ottoman world was final and history appeared to have moved on, leaving the Ottoman region behind. It was time to catch up.

Post-Ottoman policies tended to treat modernisation as a package of inseparable features: secularism, stock markets, universal education and the European alphabet were considered of a piece with staff notation, pianos and symphony orchestras. Beginning in 1928, the Ottoman Sufi orders which had for so long provided many of the most influential figures of Ottoman music were suppressed, their meeting-places locked and their ceremonies forced underground. The secular concert hall was promoted as the ideal setting for Turkish music of all kinds, where a stage, applause, tuxedoed performers and ensembles with conductors created a museum-like neutrality for musical practices shorn of their historical contexts.

Perhaps the most far-reaching legacy of the post-Ottoman reform period is the historical schism set up between monophonic and polyphonic musical practices. Taking Europe’s unique historical development from monophony to polyphony as the exclusive standard, Ottoman makam music had not even reached the Renaissance. The German composer Paul Hindemith, a consultant on Turkish music education, said in his final report to Atatürk in 1938 that Turkish makam music is ‘unsuited to polyphonic treatment – and in all attempts to develop music an ordered combination of various voices is essential.’8 The choice was clear: the way of melody leads back, the way forward was with harmony. It is this newly secularised and western-leaning environment in which the idea of a ‘classical’ Turkish music was born.

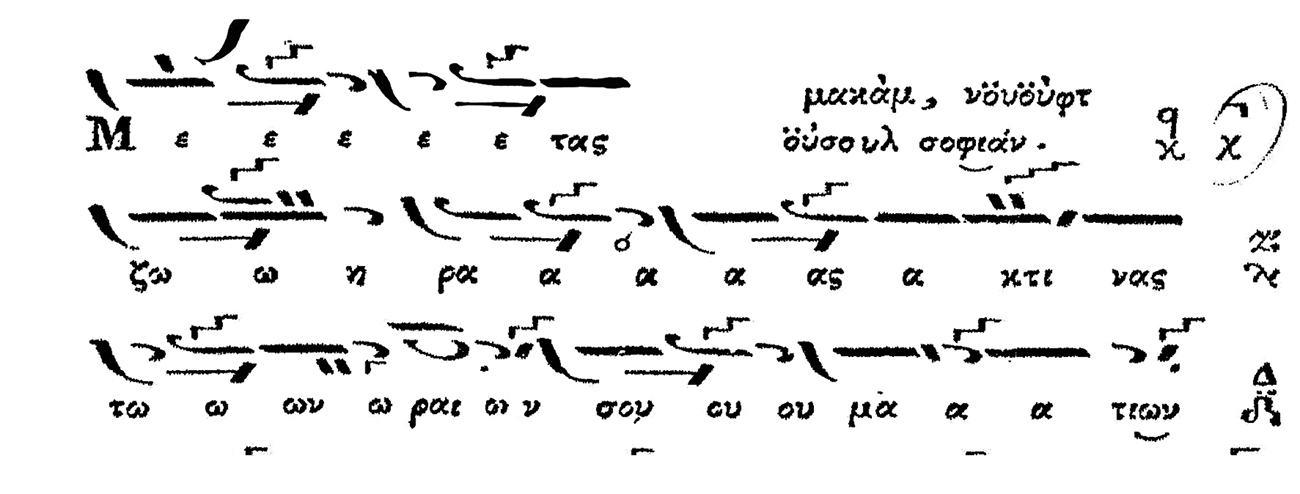

As an introduction to both Ottoman music of the past and current Turkish practice, consider the notation of a nineteenth-century Ottoman song in Example 13.1, published in the early 1980s in Istanbul.

Come, you tall beauty, tomorrow

Let us secretly walk over to the river at Göksu

Hidden from others’ eyes

Let us secretly walk over to Göksu

You are a rose bud, a flirtatious blossom

Take delight and open your eyes, smile a little

You have not gone in two years, at least this Summer

Let us secretly walk over to Göksu

EX. 13.1 Gel seninle yarın ey serv-i revan, a classical song (şarkı) by Hacı Sadullah Ağa (1760–1825)

(1) Hacı Sadullah Ağa (1760–1825), the composer of this song, was a famous Ottoman singer and court musician and a contemporary of Beethoven (1770–1827). The son of a famous religious singer, at an early age Sadullah was offered a place in the palace school in Istanbul by Sultan Abdülhamit I (r. 1774–89) to be trained in music, languages and literature. He served as a palace musician for much of his adult life. This is his traditional Ottoman name: Hacı tells us that he had made the pilgrimage to Mecca (hac) and Ağa means ‘lord’ or ‘master’, suggesting that he was of the landowning class. Sadullah, his given name, is Arabic, meaning ‘blessed of God’. Following the Ottoman custom Sadullah had no surname. To a Turkish reader, the very name of this composer would immediately evoke a bygone era.

(2) Ağır aksak is the name of the song’s rhythmic cycle or usul, a key feature of Ottoman musical form. The 9/4 metre signature and metronome marking (q = 60) are redundant twentieth-century adaptations: ağır aksak itself stands for a nine beat cycle in a particular pattern of weak and strong beats divided 2–2–2–3. Ağır means ‘slow’, ‘serious’ or ‘heavy’ and indicates a slower tempo. Aksak means ‘limping’, a term assigned to some cycles combining groups of two and three beats.

(3) Hicazkâr şarkı refers to the song’s melodic mode, Hicazkar makam, with a basic scale form of G–A –BB–C–D–E

–BB–C–D–E –F#–G, and its general form, şarkı. The flat and sharp symbols at the beginning of each new line (4) mimic the familiar western key signature which signals which accidentals to expect, but the word Hicazkâr itself actually tells a musician more about the scales, accidentals and melodic behaviour of the piece than a key signature.

–F#–G, and its general form, şarkı. The flat and sharp symbols at the beginning of each new line (4) mimic the familiar western key signature which signals which accidentals to expect, but the word Hicazkâr itself actually tells a musician more about the scales, accidentals and melodic behaviour of the piece than a key signature.

The notation used here relies on western musical conventions, first introduced in the nineteenth century – including the five-line staff, fractional note values (½, ¼, ⅛) and key and metre signatures. Some of the Turkish accidentals are different from western standards, suggesting more pitch choices than on the piano: for example, ‘backward’ flats (B) and flats with a slash ( ). Accidentals change in this piece, suggesting the presence of something like modulation in Western music. Also, the notation is monophonic: it only represents the pitches and rhythms of a melody, with no harmony implied and no special parts for instrumental accompaniment.

). Accidentals change in this piece, suggesting the presence of something like modulation in Western music. Also, the notation is monophonic: it only represents the pitches and rhythms of a melody, with no harmony implied and no special parts for instrumental accompaniment.

(5) Poetry. Translation aside, the poetic craft of this two-stanza poem – its rhyme scheme, uniformity of 11-syllable lines and repetition of refrains – catches the eye. In the 1980s, some fifty years after the end of Ottoman rule, and after nearly a century of language and alphabet changes, the editor of this notation added explanatory information. The patterns of nonsense syllables at (6) (fâilâtün [feilâtün] fâilâtün fâilün) represent the poetic metre of each line (vezin), a method of teaching and composing poetry inherited from the Arabs and Persians and developed further by the Ottomans. The editor’s glossary (7) provides Arabic or Persianate expressions (left side) with their modern Turkish equivalents (right side), like some modern English editions of Chaucer and Shakespeare.

The place to begin any discussion of Turkish makam music is where any Turkish musician would begin, with the concept of makam itself. The word ‘makam’ cuts across too many familiar conventions to be captured in a single term from the European tradition. It is best approached from three overlapping points of view: first, from a general perspective, as an abstract term; second, from the perspective of performers and composers; and third, from the perspective of the listener.

In its most general sense, makam is a melodic system encompassing both composition and performance and the entire historic repertoire of Turkish music, as in the phrase ‘Turkish makam music’. Turkish theorists today list at least sixty makams, perhaps one hundred and twenty if we include less common ones. Makam, in this sense, is a kind of a filing system for the whole repertoire. A piece or improvisation not classifiable by makam would be anomalous.

To composers and performers, a makam is a strategy for creating new melodies – part scale, part melodic template, part aesthetic rule book. In the traditional oral training of meşk, the student imitates the most minute details of intonation, style and gesture characteristic of each makam. Performing and composing in makam are treated as one practice: as you learn by imitation to recreate the work of past musicians, you are also learning to create for yourself.

To audiences, every melody in Turkish makam is heard as a member of a particular melodic family exhibiting common behavioural traits. Like any human family, all melodies in Hüseyni makam, for example, resemble each other and are different from other melodic families, even though each individual melody in the family is unique. But Hüseyni, like a human family, is also potentially infinite: the number of unique melodies creatable from the pool of Hüseyni traits is endless and the makam is always growing, as performers add new qualities to the pool. Knowledgeable listeners can hear and appreciate fresh revisions to a makam, but they will also be alert to perceived violations of its identity.

The Mediterranean culture that the Ottomans inherited through the Christian Byzantines brought with it the traditions of pre-Christian Greek music theory, which the Arabs had translated from classical Greek writings in the eighth and ninth centuries. What Ottoman and Arabic theorists called the science of music (ilm-i musiki) included the structure of tetrachords and scales, and mathematical theories for the systematic tuning of intervals – the same science brought into European music in the Middle Ages.

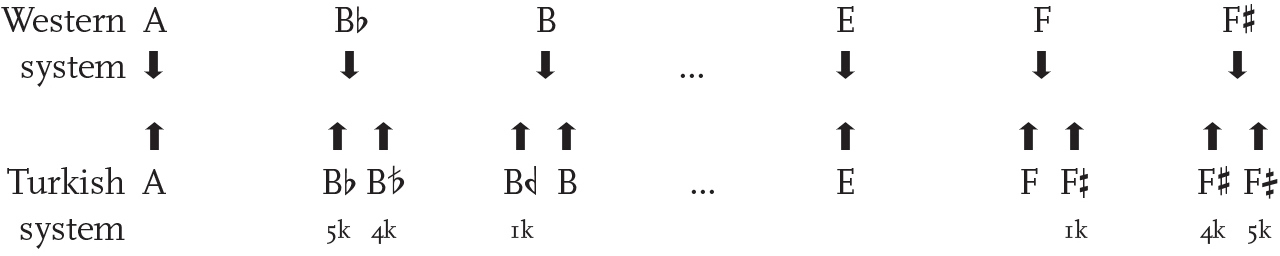

Familiar as the Turkish notation system now looks (as in Example 13.1 above), the pitches represented by the notes on the staff are actually different from those on the piano. In the West, the whole step (for example, A–B or C#–D#) is divided in two equal parts. In Turkey, each whole step is divided into nine equal parts, each part called a koma. This is what the musicians expect to hear when the notation is executed. In notation, there are just three sharps and three flats (not nine), representing the most common ways that the whole step is divided in practice, and performers treat those six accidentals flexibly, sometimes flatter and sometimes sharper depending on context.

The following diagram compares Turkish and Western flats and sharps, showing how the pitches in the two systems do not line up. (1k, 4k and 5k = 1 koma, 4 koma and 5 koma)

Within Turkish makam music these tiny discriminations of pitch – for example, between a Bb (5 komas) and a B (4 komas) – are important traits distinguishing one makam from another.

(4 komas) – are important traits distinguishing one makam from another.

The Arabs also passed to the Ottomans the classical Greek method of constructing scales with the tetrachord (fourth) and pentachord (fifth), four-note and five-note scale-wise sequences of pitches which in modern Turkish music are the basic building blocks of every makam. In practice, tetrachords are concise transposable pitch groupings, which signal to the listener and performer the cues to melodic families. Moreover, new makams are invented by re-combining familiar tetrachords. Not unlike modulation between different keys in Western harmonic music, modulation from one makam to another harnesses distinct makam identities to create subtle and sometimes dramatic contrasts. Often very slight alterations of a tetrachord can provide the connection to another makam.

But any Turkish makam musician will tell you that the most important aspects of makam are not its objective scales, tunings and tetrachords, even though conversation among musicians is impossible without them. Two modern concepts now embody the subjective aspects of makam: characteristic melodic gesture or çeşni (‘flavour’), and characteristic melodic pathway or seyir (‘journey’, ‘progress’). These old terms have risen to standard usage in makam pedagogy only since the mid-twentieth century.

A çeşni, also referred to as a stereotyped melodic phrase, is a small nugget of makam identity, usually incorporating only a few pitches. A well-known sequence of tones – a kind of tune fragment – can immediately trigger a listener’s memory of repertoire in a particular makam. In this respect, çeşni is comparable to allusion in poetry where the poet may trigger a whole cluster of associations to a familiar phrase. Like poetic allusion, çeşni can deliver depth and richness of detail in a single condensed utterance.

Seyir, or melodic pathway, has become the single most important feature of a makam in post-Ottoman pedagogy. The term is now used in three ways:

◆ Seyir is a general word for the sum of all the subjective qualities of a makam – the behavioural tendencies which characterise it.

◆ Seyir may also stand for three standardised paradigms of melodic direction a makam may follow – ‘ascending’ (inici), ‘descending’ (çıkıcı) and ‘ascending-descending’ (inici-çıkıcı). The three typical pathways are summarised as a line connecting a melody’s beginning and ending pitches. Uşşak, Hüseyni and Muhayyer makams, for example, have nearly identical scales (A–BB–C–D–E–F[#]–G–A), but their seyirs differ: Uşşak melodies (ascending seyir) start around A (its karar or final), rise, then fall to the A; Hüseyni melodies (ascending–descending seyir) start around E, rise to the upper octave, then fall to A; Muhayyer melodies (descending seyir) start around the upper octave and fall to the A. Aesthetically, the three paradigms come across as gravitational metaphors, with the karar as the force drawing all melodic movement down to a conclusion. Seyir is also a vocal metaphor: tension increases and decreases as the voice moves higher and lower in the singer’s range.

◆ Seyir can also be a model melody, created on the spot by a teacher to illustrate the essential progression of the makam. However, existing repertoire and recorded taksims (improvisations) by respected musicians remain the preferred exemplars of seyir.

With regard to the metre the oriental music surpasses highly the European music. There are twenty-four kinds of metres (which are called usul) by which the pace of time is measured. [Thus], there is great difficulty in singing correctly and perfectly, as well as [in playing] exactly the songs on an instrument because every author strives to compose songs at his pleasure with the metre and rhythms he likes, and because they are so intricate, those who do not know the metre cannot play the songs at all, even though they were to hear that song a thousand times…

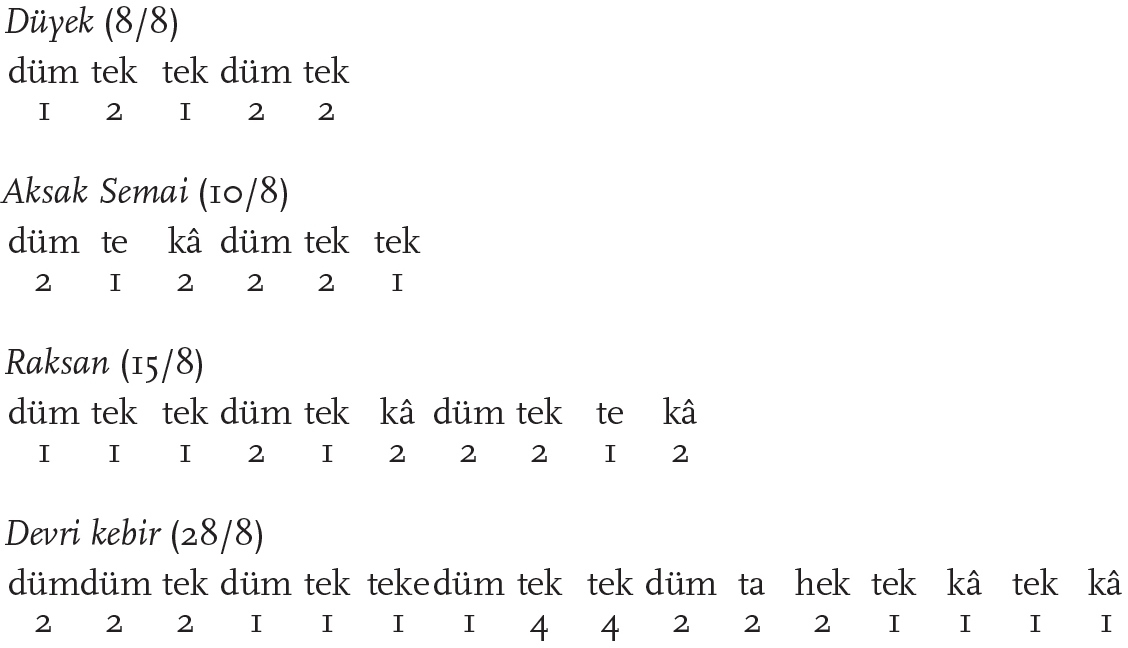

Prince Dimitrie Cantemir, 17349

Putting Turkish makam music in the simplest possible way, once a musician or a listener is equipped with the detailed and fluid melodic paradigms of makam, then that melodic material may be poured into a particular pattern of strong and weak beats (usul) to construct clear and replicable musical forms with a distinctive character. A single cyclical pattern may range in length from two beats to 120 beats, a repertoire of more than a hundred different patterns from which a composer may choose. Here are a few of the most common patterns in use today, presented in a combination of western-style note values with the syllables dum and tek (inherited from Arabic music), which stand for heavy and light beats on a drum. Usul is thus an notation of an exemplary rhythmic accompaniment as well as a compositional paradigm.

Until the twentieth century, this system of rhythmic cycles also went by the Arabic name iq’a (‘falling’ or ‘causing to fall’). The term used today is the Turkish word usul, with a non-musical meaning of ‘method’, ‘order’ or ‘manner’. Limiting usul to the Western notion of metre robs it of some of its richness: usul is today written like the familiar Western time signature (4/4, 6/8, 10/8 and so on), but it also conveys a sense of tempo, quality of motion and melodic style. So-called ağır (‘heavy’) usuls (see Example 13.1) tend to move at a slower pace, leaving more room for subdivisions of the beat, while cycles that are yürük (‘fast’, ‘light’) tend to be quicker. A song in an ağır cycle will tend to be more melismatic, with more notes per syllable, giving it more formality than a yürük cycle, which will tend toward more syllabic settings with one note per beat.

But until the twentieth century, usul was also a way that musical forms were composed, fixed and remembered in the primarily oral tradition of Turkish makam music. The Moldavian prince Dimitrie Cantemir (1673–1723), an influential Ottoman composer and theorist in his own right, compared musical metre in Turkish makam music with the idea of preserving compositions in notation, noting that ‘the composers of songs do not indicate the pitches and the time value, which are extensive yet easy usage for Europeans’. Usul, he says, provided the structure by which pieces were remembered and transmitted ‘without error’ in the absence of notation. Even today, musicians will rehearse a piece in the traditional manner by singing it to themselves while tapping their hands on their knees, düm-tek-tek-düm-tek, right–left–left–right–left, the shape of the heavy and light beats providing a mould into which the voice pours the makam.

By the eighteenth century, it seems that musicians were as engaged in inventing new rhythmic structures as they were in inventing new makams. New usuls could be created by recombining short modules of existing usuls or by creating longer compound structures, the rhythmic analogy to compound makams. For example, Zincir usul (120 beats), already in use in the seventeenth century, is composed of five shorter usuls strung together: 16 + 20 + 24 + 28 + 32.

From usul it is an easy transition to musical form in Turkish makam music. Usuls establish the rhythmic mould of a composition – the strong and weak stresses that give melody a lasting and memorable shape. The gravitational pull of makam away from and toward a karar, or final pitch, also articulates form, comparable to the ‘home and away’ harmonic movement of Western music over at least five centuries. A few examples of traditional genres will illustrate the shaping power of makam and of usul, and even of the absence of usul.

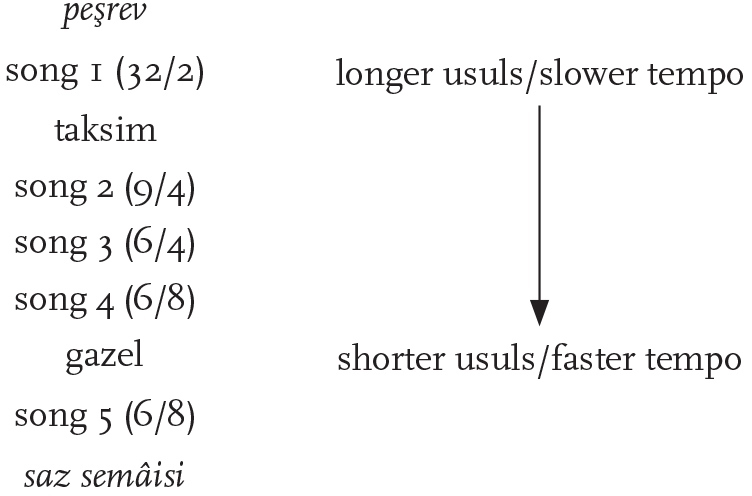

The performance described at the opening of this chapter was a version of the traditional Ottoman suite of secular vocal pieces known as fasıl which has parallels in the wasl, muwashshah and nuba of North Africa and the Middle East. The following diagram shows a modern example (1990) of fasıl performance by the Kudsi Ergüner ensemble, the structure is a lighter and shorter version of the more rigidly ordered eighteenth-century fasıl, with just five songs played without pause.

The songs are framed by an instrumental prelude called peşrev (from peş, Persian for ‘head’) and an instrumental postlude called saz semâisi (‘instrumental listening piece’). Makam unifies the suite: all the songs are in either Hicaz makam (A–B –C#–D–E–F#–G–A) or the closely related Hicaz-Hümâyûn makam (A–B

–C#–D–E–F#–G–A) or the closely related Hicaz-Hümâyûn makam (A–B –C#–D–E–F–G–A). Following the earlier Ottoman model, usul provides this suite’s structural logic, with the songs (by a variety of composers over three centuries) arranged from longest and slowest usuls to shortest and fastest, creating a gradual build in excitement over about thirty minutes.

–C#–D–E–F–G–A). Following the earlier Ottoman model, usul provides this suite’s structural logic, with the songs (by a variety of composers over three centuries) arranged from longest and slowest usuls to shortest and fastest, creating a gradual build in excitement over about thirty minutes.

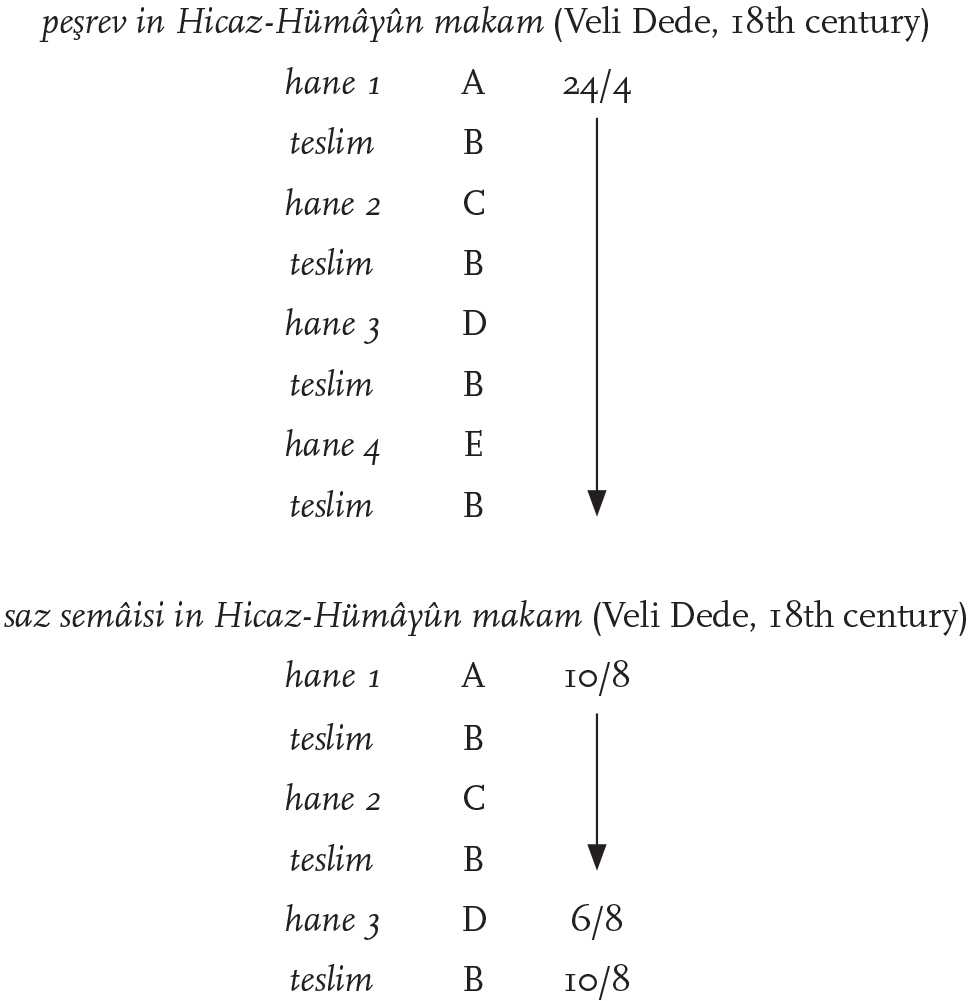

The fasıl’s peşrev and saz semâisi, composed in Hicaz-Hümâyûn makam by the eighteenth-century composer Veli Dede, have an identical rondo-like form in which three or four sections called hane (‘house’, ‘place’) alternate with a recurring teslim or refrain (see the following diagram). But for composer, performer and listener alike, it is usul which distinguishes the two otherwise identical forms in the same makam. The steady tempo and duple feel of the peşrev in Çember usul (24/4) clearly sets it apart from the saz semâisi, shaped by the limping rhythm of aksak semai usul (10/8) and the fast waltz time of yürük semai usul (6/8).

Key instruments in Turkish maqam ney, oud, kanun, tanbur, rebab, bendir. The tanbur has become an icon of Turkish makam music’s refined sense of pitch, with room on its extremely long neck for forty or more adjustable frets. Only the kanun, with its ten to thirteen tuning levers per course, fully expresses in hardware the Turkish system’s nine divisions of the whole step.

The instrumental taksim and the vocal gazel are examples of makam artistry illustrating how usul is important, even when absent. Both forms have been featured in the fasıl since at least the eighteenth century, where their free rhythm melodic movement provides contrast within the usul-based logic of the suite. Turkish listeners are likely to hear the unmetred taksim and gazel (sometimes called ‘vocal taksim’) as akin to Qur’anic chant (tilavet), which by Islamic tradition is never to be metrical or pre-composed. Any singer capable of the various types of free-rhythm, improvised song is probably a hafiz, a singer (traditionally male) who has been rigorously trained in his youth in the traditional science of Qur’anic chant (tecvid), learning how to make makam the vehicle for the Angel Gabriel’s Revelations in Arabic to the Prophet Mohammed in the seventh century. The career path of many a famous twentieth-century secular recording artist began with training as a hafız. These indirect associations of free rhythm and performer-control with Muslim spirituality are likely to lead many Turkish listeners to hear a special seriousness and emotional depth in taksim and gazel, regardless of the setting.

Despite the suppression of Turkish Sufi orders by the government throughout much of the twentieth century, their repertoire has found a place in performance and pedagogy. Students often learn Sufi devotional vocal genres such as the ilahi and nefes, less for their ritual meaning than as concise models of a makam’s seyir. Ayin, the music of the famous whirling ceremony or sema of the Mevlevi brotherhood, has also become a concert staple, sung or played instrumentally. The ayin’s four-movement form is a setting of the Persian poetry of Mevlana Celaluddin Rumi (1207–73), the founder of the Mevlevi order. The energy of the ayin moves fasıl-like through a metrical logic from longer, slower usuls with subdivided beats to faster usuls with one note per beat, with taksim providing a free-rhythm contrast at the beginning and end.

Turkish musical instruments are as much the product of the aesthetic values of makam music as they are the creator of those values. Many of these instruments are shared by other peoples of the Mediterranean region who are part of the larger makam-playing family: the short-necked lute (oud), the zither (kanun), the end-blown cane flute (ney), the short, bowed pear-shaped fiddle (kemençe), the bowed spike fiddle (rebab), the circular frame drum (bendir), the goblet drum (darbuka) and the frame drum with brass jingles (def). But the small copper kettle drums (kudum) and the long-necked lute (tanbur) are today primarily limited to Turkey. The tanbur has become an icon of Turkish makam music’s refined sense of pitch, with room on its extremely long neck for forty or more adjustable frets. Only the kanun, with its ten to thirteen tuning levers per course, fully expresses in hardware the Turkish system’s nine divisions of the whole step.

Photographs may illustrate the basic structure, shape and size of the instruments used in Turkish makam music, but there is much that is important which is not visible. Two tendencies in Turkish instrument design are well-matched to monophonic makam performance: first, instrument-building has favoured idiosyncratic sound qualities over technical expansion; second, instruments and instrument-playing tend to be modelled on the human voice.

A theme of Western instrument evolution has been the restless experimentation with hardware and technique to enhance uniformity of tone, tuning and agility from top to bottom of the range. By contrast, consider the Turkish ney, consisting of a length of hollow reed with six finger holes and a thumb hole and a mouthpiece of buffalo horn, virtually unchanged since the thirteenth century, even as the number of makams and the tendency to modulate has grown. The Western flute’s ‘pure tone’ allows the instrument to maintain its precise place in harmonic textures while, in its ideal solo or small group setting, the rich and fat tone-colour of the ney satisfies the ear with the complexity of each pitch. The orchestral flute can reliably execute twelve pitches per octave with great agility and accuracy, but on the slower-moving ney, any pitch can be altered nearly a whole step by subtly tilting the head, allowing the player to bend and sculpt each pitch.

The capacity of the human voice to infinitely mould pitch and to create an individualised sound is still the essential benchmark of Turkish instruments, whether plucked, blown or bowed. The natural human voice-range of about one and a half octaves is reflected in the tendency for even instrumental repertoire to stay within those limits, and contrasts sharply with the piano’s eight octaves and the six octaves of nineteenth-century orchestral music.

Since the early twentieth century vibrato has become a default practice for Western vocal music and stringed instruments, even in large ensembles. In makam music, vibrato is selectively employed, one of an array of techniques for shaping melody. On a sustained note, players of kemençe, rebab or violin, for example, often execute the initial attack without vibrato, gradually adding an expressive end to the pitch. The default lack of vibrato in voice and instrument once again focuses the ear on nuances of melodic treatment and fine gradations of pitch. For Western classical musicians attempting to learn makam performance style, the selective and controlled use of instrumental and vocal vibrato is often a difficult hurdle, requiring a restructuring of technique and performance habits from the ground up.

From this it may be said that French Music is simple, noble and natural; Italian Music lively, animated and attractive; and Turkish or Oriental Music soft and luxurious.

Charles Henri de Blainville, 176710

The impression of softness and luxury which the eighteenth-century French musician, scholar and traveller Charles Henri de Blainville heard in Turkish music was no doubt coloured by the contemporary European view of ‘Oriental’ culture itself as degenerate. The following general characteristics both summarise and supplement what has been said so far about Turkish makam, usul, repertoire and instruments. Just as Blainville (whose writings showed an unusual openness and empiricism) continually compared Turkish music with the music he knew best, the following concise characterisations are intended to direct attention to what may strike Western listeners as distinctive about the current practice of this music in Turkey.

It is monophonic, but its textures are often complex. No matter how many Turkish musicians are playing together at one time, they all focus on executing a single melody line, though each may interpret it differently. This monophonic orientation has always been a problem for Western observers. The French traveller Michel Febvre observed in 1688 that the Turks ‘do not know music and have only the simple unison’.11 The absence of the familiar harmony of his own music felt to Febvre like a deficit, comparable to a human with only one eye. Febvre came by these views honestly: Western histories from the Enlightenment to the present have tended to narrate Western musical development as an inevitable ten-century progression from simple to complex, from single- to multi-voiced music. From this perspective, monophonic music would be analogous to either European medieval or peasant music, where monophony has also continued to thrive. But in Turkey, monophony as a music-making strategy – and the tendency to preserve single melodic lines in notation – has in no way ruled out complex textures, or the interaction of multiple voices in performance.

Ottoman makam written in staff notation (but read right to left) by Ali Ufki (1610–75), originally a Polish church musician named Wojciech Bobowski who became a slave in Istanbul, converted to Islam and became one of the Ottoman empire’s leading composers.

Fifty years later the Moldavian prince Dimitrie Cantemir (1673–1723) was enslaved in a similar way, and notated makam in a way which respected the refinement of its intervals.

Evterpi (1830) – Byzantine notation of Ottoman makam, with Turkish song texts written in Greek letters

It is an oral tradition, but it has created a place for musical notation. Staff notations can be found on the music stands of many makam music sessions in Turkey today. Less obvious are the handful of Ottoman repertoire collections created in a variety of notation systems from the mid-seventeenth to early twentieth centuries. And yet, unlike in Europe, the science of notation remained marginal in Turkey until the twentieth century. Illustration 13.10 shows the work of the renowned musician and linguist Ali Ufki, born Albert Bobowski (1610–75), a Polish Protestant. Taken captive by the Ottomans as a young man, he converted to Islam and rose to a position of influence as a translator and musician in the Ottoman court, living most of his life as a slave (kul) in the Ottoman domains. His manuscript collection of more than a thousand instrumental and vocal pieces represents the first application of Western staff notation to Ottoman music. (Note: the notation is read from right to left, as in Arabic script.)

This and most other examples of Ottoman notation were executed either by Muslim converts like Ali Ufki, or by non-Muslims such as prince Dimitrie Cantemir, who created his own variant of earlier notations based on the Arabic alphabet, or the Armenian Hamparsum Limoncuyan (1768–1839), who adapted the notation system of Armenian church music. In the nineteenth century, lavish collections of makam music were also published in the musical writing system of the Greek Orthodox Church for the benefit of educated Greek-speaking Ottomans. All these examples may be taken as possible outcomes of an Ottoman inclination westward, and of a long-standing Ottoman policy encouraging diversity.

In 1826 the Italian bandmaster known as Donizetti Paşa (Giuseppe Donizetti, 1788–1856, brother of the opera composer Gaetano) was invited to adapt European instruments, notation and pedagogies to the palace orchestra for sultan Mahmud II. In the early twentieth century, a program of systematic conversion of Ottoman repertoire to staff notation began in earnest. Today, music students spend much of their lesson imitating what the teacher plays, but they are also expected to sing fluently from notation using solfège like their counterparts in Paris and New York.

It is performer-centred, but it reveres composers. Today, Turkish makam musicians take greater liberties with the preserved music of the past than do their counterparts in the West, where musicians have evolved into two groups of specialists – composers who create music, and performers who execute the composers’ written scores. A Turkish makam musician of today – like the ideal musician in Europe until around 1825 – is one who can read notes fluently and accurately, but who is expected to personalise and elaborate on pre-composed pieces, to create preludes and interludes around them, and to make his or her own music, with or without notation. By the First World War, the only Western repertoire where the roles of performer and composer are blended in this way was the African-American art form, jazz. The term usually applied today to performer-generated composition is ‘improvisation’, now considered a specialty of jazz. Turkish musicians sense that these different expectations of Western audiences can lead to a misunderstanding of their music: the multi-instrumentalist İhsan Özgen’s description of makam music as ortadoğu cazı (‘Middle Eastern jazz’), attempts to bridge the gap. But there is no general Turkish equivalent to ‘improvisation’, making it an uncomfortable fit for makam music. In this chapter, descriptive expressions like ‘performance generation’ and ‘performer-controlled’ have been preferred.

It is an art of continuous variation, but it values fixed compositions. Because Turkish performers create individualised renditions in every performance of a composition, each of those performances can be strikingly different. When two or more performers simultaneously create different interpretations of the same melody, the result is elaborated unison or heterophony. Three players playing from an identical notation will probably find opportunities to insert their own connective passages, slides, sustained notes, delayed attacks, elisions and decorations. Each will take moments to withdraw into the background or to project into the foreground. Individually transcribed, each player’s part would look quite different and the composite sound is rich and multi-voiced. Makam itself provides each player with a more comprehensive model of how a melody is to go than is simply found on the page. Musicians understand that the composer’s notated melody is a variant of the makam, which is itself infinitely variable.

Its concerts are secular, but much of its repertoire has roots in the sacred. Since the end of Ottoman rule, public concerts of Turkish makam music have conformed to the secular framework of the Western concert hall. But the repertoire and practices of mystical Islamic devotional music, its ritual meanings muted but not erased, have been adapted for performance alongside secular urban love songs and Ottoman instrumental pieces. The secular free-rhythm taksim and gazel, and the art of the Qur’anic chanter, have roots which intertwine, and much of the ostensibly secular love poetry of Ottoman song is infused with the vocabulary of Islamic mysticism. Even the peşrev, the instrumental prelude to the secular Ottoman suite, has a long association with the Mevlevi whirling ritual, and the cane flute remains linked in Turkish perception with the fourteenth-century Sufi poetry of Celaluddin Rumi: ‘Listen to the reed and the tale it tells / how it sings of separation: ever since they cut me from the reed bed, / my wail has caused men and women to weep…’12

One must beware of mistaking for genuine Turkish military music that Janissary music… for which new pieces from German pens appear daily. The difference between both is endlessly great. Our German-Turkish military music cannot even boast the same instruments, much less the same taste.

Franz Joseph Sulzer, 178113

The musical technique of the West is, among all others, the most evolved, the most precious and the most powerfully expressive… Our national music will be born when our national melodies will be set according to this technique. Our musical future depends on it. It is truly our single hope for the future.

Halil Bedii Yönetken, Director General of the Fine Arts in Turkey, 192414

These observations by two influential figures in eighteenth-century Germany and twentieth-century Turkey suggest that cultural influence between the Ottoman regions and Europe has been, in the long run, a two-way street. Franz Joseph Sulzer bears witness to one phase of the early European fascination with the ‘orient’. Halil Bedii Yönetken expresses the relatively late Turkish infatuation with all things European. The idea of a multi-century Euro-Ottoman symbiosis is still worth keeping in mind, helping to make sense of this perennial two-way traffic.

In the story of mutual east–west influence, the alla turca phenomenon is a key element. This popular faux-Turkish style lasted more than a century and found its way into opera, orchestral and chamber music scores by Rameau, Gluck, Mozart, Haydn, Beethoven, Mendelssohn and Rossini, to mention just the most famous of the ‘pens’ Sulzer alludes to. Ottoman ceremonial wind and percussion ensembles called mehterhane struck European travellers as novel, inspiring imitations called ‘janissary bands’ or bando turca which could be heard frequently on the street corners and stages of European cities. But by 1826, more than a century after the Ottomans’ last unsuccessful siege of Vienna, the distinctive march-like bass drum and triangle of the alla turca section of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony stood less for barbarians at the gate than the populism of the European street.

The aggressive sonorities and persistent rhythm of the European variants on Ottoman mehterhane captured the popular Western view of the barbarity and violence of the East, crowding out all other models of Ottoman music. This is the quality and the instrumentation which evolved over three centuries into what is now the marching band, spawning a global array of adaptations, including jazz, all featuring the uniquely Ottoman combination of winds, cymbals and drums.

The story of this peculiarly European and militaristic ‘Turkish’ style took an ironic turn in the nineteenth century. When Donizetti Paşa introduced European instruments and notation to Turkey at the request of Mahmut II, his musical mission was part of a much larger westernising effort. In a parallel move, the disbanding in 1826 of the historic elite Janissary corps (yeniçeri) required the creation of a new European-style army with a new European sound. A Western-style marching band of European brass instruments – the heir of Europe’s alla turca craze – replaced the mehterhane that had inspired it. What had arrived in the West in the sixteenth century as an oriental import came back to the East, three centuries later, as an occidental import.

The monophonic nature of Turkish makam music – its emphasis on conversational interaction among performers engaged in continuous variation of melody – allows it to stand out in the global array of musical practices. Perhaps the long history of European and Ottoman interaction has positioned the Ottoman musical heritage to help carve a niche for monophony in a world dominated by Europe’s peculiar model of polyphony. As Turkish makam music perpetuates the blended role of composer-performer abandoned by Western classical music, it continues to emphasise oral transmission of melodies supplemented by notation. It persists in cultivating the low-tech refinement and vocalism of its instruments, lending the music a non-technological quality and a human scale. This music may have been born in a theocracy, but its intimate textures are transparent, with every voice heard, creating musical events which are responsive to both performers and audiences – qualities well-matched to rising global expectations of institutions which are participatory and transparent.

Moreover, makam music in all its Mediterranean vernaculars still possesses infinite possibilities, leaving room for endless expansion of its vocabulary through continual variation in performance, and through its long-standing invitation to invent new modal and rhythmic structures out of old ones. While Turks and non-Turks continue to market makam music as a nostalgic phenomenon, avant-garde Western art-music since the mid-twentieth century has increasingly explored open-ended structures, unrepeatable events, indeterminacy, performer control and audience interaction – all qualities compatible with an Ottoman model. Unlike European listeners of the past, we can now hear Turkish makam’s monophonic musical strategies not as outdated, but as sympathetic to at least some of the newest trends in Western music. This may point to the advent of a new kind of Euro-Ottoman synthesis.

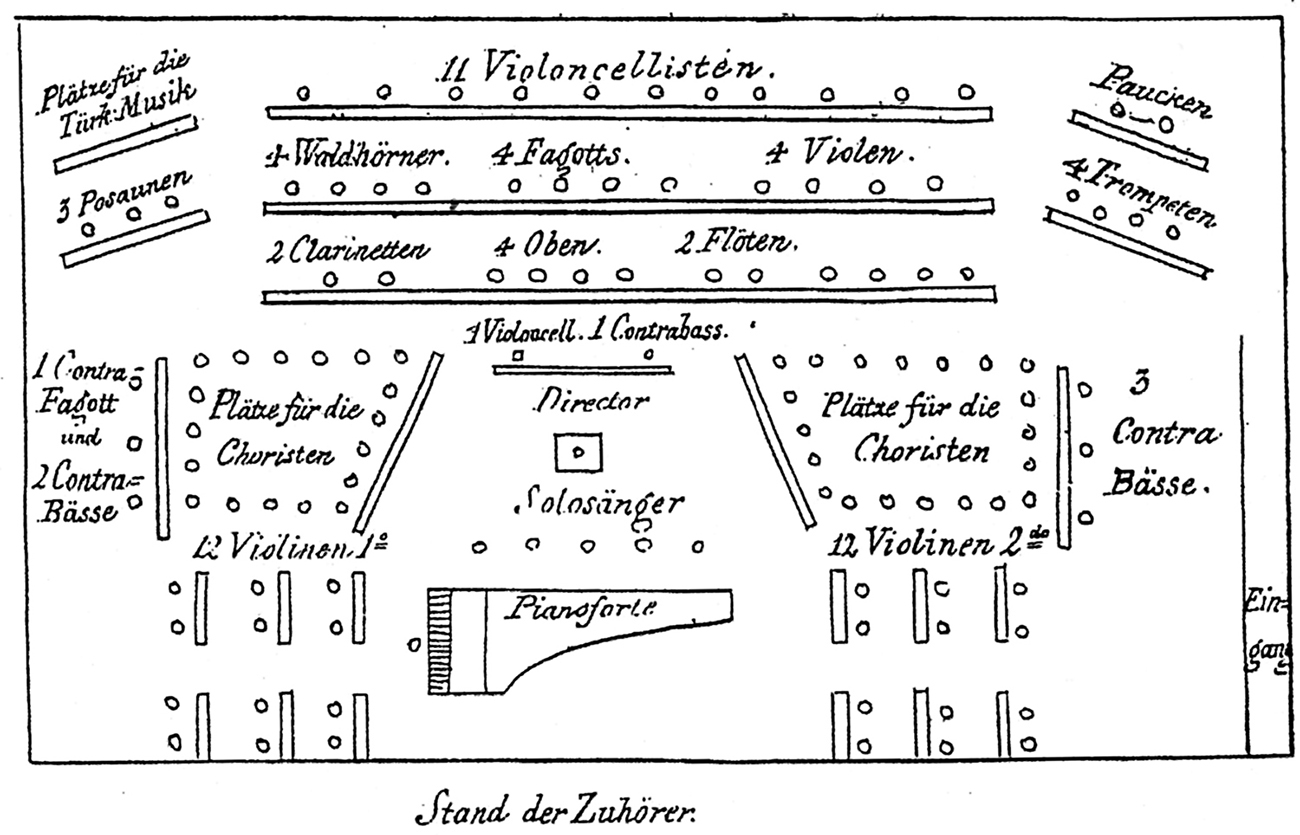

The seating arrangement for a large orchestra in Paris in 1810. In addition to places for trombones (Posaunen), timpani (Pauken) and trumpets (Trompetten), places are reserved (upper left) for Turk Musik (instruments unspecified).

Further reading

Eliot Bates’s Music in Turkey provides a readable introduction to the contemporary Turkish music scene for a general audience, with an accompanying CD. This is a realistic and pluralistic view in which Turkish makam music, like classical music in Britain and the United States, continues to be important for a relatively small audience, but does not dominate public attention. Various shorter articles in The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music vol. 6, The Middle East are also intended for non-specialist readers, focusing on selected topics rather than general introductions; the volume also includes a CD of examples. For those desiring a more detailed source on Turkish makam practice, Murat Aydemir’s Turkish Music Makam Guide is a concise manual of sixty makams with recorded examples, presenting the scale, general behavioural characteristics and a sample composition in notation for each makam. The most authoritative historical study in English of the Ottoman classical repertoire is Walter Z. Feldman’s Music of the Ottoman Court, though it is not intended for a general readership and is focused primarily on instrumental music. Miriam Whaples’s ‘Exoticism in Dramatic Music’ and Benjamin Perl’s ‘Mozart in Turkey’ are examples of the considerable literature on Europe’s fascination with the exotic, and especially the alla turca phenomenon of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Donald Quataert’s The Ottoman Empire is an excellent and readable example of the new Ottoman historical writing which argues for a more interconnected picture of Euro-Ottoman relations.

A profusion of internet sites created by an international mix of Turkish music enthusiasts may be accessed by simply searching for relevant keywords. These sites are motivated by interests ranging from the commercial to the nationalistic, so let the reader beware. The online catalogue of Kalan Müzik (http://www.kalan.com) is the best one-stop site for browsing and buying high quality Turkish recordings from classical to folk and pop, and in recent years Neyzen.com (http://neyzen.com) has made itself the best single source for notations of Turkish music, organised by makam. Both of these sites have options for readers of English.

Recommended listening

Re-issues of earlier 78 and 331/3 rpm recordings which have become the benchmarks of twentieth-century musicianship include:

Tanburi Cemil Bey [1910–14], 3 vols, Traditional Crossroads 4274, 1994–5. The most revered of all late Ottoman musicians, a multi-instrumentalist virtuoso who lived from 1871–1916.

Gazeller, 3 vols [c. 1910–50s], Kalan 67, 072, 360, 1997–2006. Secular vocal improvisations on Ottoman poetry, mostly by singers trained in koranic chant.

Niyazi Sayın and Necdet Yaşar [1950s–80s] (2 CDs), Kalan 361, 362, 2006. Schooled in the recordings of Tanburi Cemil Bey, this ney and tanbur duo set the standard for later twentieth-century performance.

Recent performances of a range of repertoires and approaches by leading musicians, all of whom recognise earlier performers like those above as their standard:

Salih Bilgin and Murat Aydemir, Nevâ, Kaf KB 01 34 Ü 1327 022, 2001. A ney and tanbur duo in the generation after Niyazi Sayın and Necdet Yaşar.

Bezmara, Kalan 296, 2004. An example of ‘historical performance’ in recent Turkish music using reconstructed instruments and carefully researched repertoire from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Yahudi Bestekarlar, Golden Horn 501257 2, 2001. Recent performances of compositions by the most famous Ottoman Jewish composers from the eighteenth to twentieth centuries.

Mevlâna: Sûzidil-ârâ Ayin-i, Kent 100172 2, 1993. A typical late twentieth-century performance of music for the Mevlevi Sufi whirling ceremony. Music by Sultan Selim III (1761–1808), words by Mevlana Celalladin Rumi (1207–73).