In a garden of cypress and pine trees under the soft summer night, tiny water-canals and candlelit paths lead to a polygonal kiosk open on all sides, with an open dais in front. Six cushions in a half-moon arrangement face an audience – men and women, young and old – seated around the stage. From behind the pavilion appear six young musicians: five men with instruments, and a woman in a white evening dress with long sleeves and high neckline; her companions are in white shirts and beige trousers. To applause they take their places on the dais and the men tune their instruments: a lute, fiddle, zither, flute and drum. Each instrumentalist is highlighted during a slow introduction, which is followed by a rapid virtuoso section on zither and drum. Singing in Farsi, the vocalist delivers an evocative line: ‘On my tomb, sit down with wine and a musician’, and the forcefully-plucked lute gives an improvised response. The two continue their exchange while members of the audience gently nod as they sing along in a whisper. The meditative mood gives way to an energetic song from singer and ensemble, and the performance ends with a lively instrumental number.

WE are in the garden of the Hāfezieh, where the Persian poet Hāfez (1326–90) is buried. This is in Shiraz, also known as the city of Gol o Bolbol (‘flower and nightingale’). Such gardens have been popular venues for the performance of Persian classical music for centuries, and for musicians, poets and philosophers they have been a refuge from daily life, with many – like the twelfth-century poet, mathematician and philosopher Omar Khayyām – choosing to be buried there: ‘My grave will be in a spot where, every spring, the north wind will scatter blossoms on me.’1

The story goes that a Persian poet was discussing music with some Westerners who compared their music to an ocean, and Persian music to a miserable drop. ‘Indeed,’ answered the poet, ‘but that ocean is only water, while this drop is a tear’.2 Essentially intimate, Persian classical music is closely bound up with poetry and mysticism, and customarily involves the singing of verses by poets such as Hafez, Sa’di and Rumi. As the leading authority on Persian classical music Nur ‘Ali Borumand (1905–77) has shown, text and music are inextricably intertwined: echoing a verse by the thirteenth-century poet Amir Khosrow Dehlavi, he once observed to the American musicologist Stephen Blum that ‘verses without melodies are like a bride without jewels’.3

The Hafezieh is a traditional meeting place for musicians and poets, and in hosting the Shiraz Art Festival in the 1960s and ’70s it became an important venue for Persian classical music. The last such event was held in 1977, just prior to the revolution which established Iran as an Islamic Republic and ushered in wholesale political, social and cultural changes. Many of these changes directly affected artists and women: the hijab head-covering was mandated by law, and women were prohibited from singing solo for any audience which included men. Musicians and composers found themselves subject to investigation and abuse from the authorities, and many fled the country. Some of these restrictions have been eased over time, but others still apply. These pressures are not new, however; they have affected Persian musicians for centuries.

Iran forms a bridgehead between the Middle and Far East, and a crossroads for migration and trade. Its history has been punctuated by invasions: by the Greeks in the fourth century BCE, the Arab Muslims in the seventh century CE and the Mongols in the thirteenth century; in modern times it has experienced two revolutions. Yet in contrast to those ancient civilisations of the Middle East which became Arabised, Iran has preserved its cultural identity, and – most importantly – its language.

It was known to the Western world as Persia until 1935, when the reigning monarch Rezā Shāh Pahlavi (r. 1925–41) requested that the international community refer to it as Iran (from middle Persian Ērān, ‘Aryan’), which was how its native population knew it. Iranians use the term ‘Persian’ (Farsi) only for language, while in the West ‘Persian’ is used to refer to Iranian culture including music, miniatures, carpets, literature and poetry. Iranian is used as a geographical term, as in ‘Iranian Plateau’, or as an ethno-linguistic descriptor as in ‘Iranian languages’.

But the label ‘Persian’ is highly regarded, implying reference to the great empires of the past beginning with that of Cyrus II (Kurosh), known also as Cyrus the Great (r. 576–30 BCE). The Achaemenid Empire which he established (550–330 BCE) stretched from the Indus valley in the east across all of Western Asia into Greece in Europe, and as far as Libya in northern Africa. Thanks to this imperial expansion, followed by the reciprocal conquests of Alexander the Great (336–23 BCE) whose realm superseded the Persian domain, the Greek connection in Persian cultural history is strong. Descriptions of Persian music during these periods come primarily from Greek historians such as Herodotus (484–25 BCE), whose exposure to music was mostly confined to military contexts. Musical exchange between Persians and Greeks is suggested by similarities of performance practice such as heterophony, and the use of musical modes for improvisation. A similar musical cross-fertilisation was fostered by trade along the Silk Road: the Persian barbat lute was the ancestor of both the Chinese pipa and the Japanese biwa.

Iran has long been home to many ethnic groups including Turks, Kurds, Baluchis, Lors and Arabs, who live mostly on the periphery of the current political boundaries; each community has its own language and musical tradition. As there are many affinities between languages and musical styles, sung poetry has long been appreciated in Iran; musicians were often poets, and vice versa. Persian classical music as practiced today developed primarily in the political and cultural centres of Qazvin, Shiraz, Isfahan and Tehran, on the central Iranian plateau. It is thought to be one of the oldest musical systems in the world, and its origins were courtly: since antiquity it has played a key role in the royal palaces. During the Sassanid dynasty (224–651 CE) poet-singers enjoyed the same high status as scribes, physicians and astronomers. The most celebrated royal patron was King Khosrow II Parviz (r. 591–628), whose love of music is still reflected in a large cliff relief in western Iran where he is shown being escorted on a riverside hunt by a band of female harpists. Khosrow’s reign represented a golden age for classical music, and, led by his court minstrel Bārbad, this music fed into what scholars now believe was a common Arabic-Persian modal system which prevailed from the mid-thirteenth century to the beginning of the sixteenth century, before dividing into separate systems.4 Many nomenclatures in Arabic, Turkic and above all Azerbaijani music are of Persian origin.

After the Arab conquest of the Persian empire in the seventh century, Persian musicians and scholars – whose culture the Arabs greatly respected – became dispersed throughout the Islamic world. Most prominent among these were Ebrāhim Mawseli (742–803) and his son Esḥāq Mawseli (767–850), Abu Naṣr Fārābi (tenth century), Ibn Sinā, known as Avicenna in the West (eleventh century), Qoṭb-al-Din of Shirāz (fourteenth century) and Abdol Qāder Marāqi (fifteenth century). The Arabs adopted the ‘Persian lute’ (‘ud fāresi), making it their principal instrument for urban and court music.5 Moreover, the performance of Persian poetry – which lay at the heart of Persian classical music – has extended at various times beyond Iran to other areas where Persian was used as a spoken and written language, such as Afghanistan and Tajikistan, plus parts of the Indian sub-continent and Turkey where literary Persian was an important cultural language. Persian poets such as Ferdowsi (tenth century), Nezāmi (twelfth century), Rumi (thirteenth century), Sai’di (thirteenth century) and Hafez (fourteenth century) celebrated music and dance, and often used instruments as metaphors for human feelings, as in Rumi’s Masnavi, ‘Song of the Reed Flute’ (see Example 14.1 below).6

Though no explicit prohibition of music is found in the Qur’an, Islamic attitudes towards music have been ambivalent: while writing about music has always been a respected intellectual pursuit, the legitimacy of listening to and performing it has been a subject of controversy among jurists and theologians. Although this has often been triggered by the association of music with indulgence in wine and sensuality, music and wine are the key components in the Persian tradition of razm o bazm (‘battle and feast’). Every ruler from the Achaemenid period until the twentieth century employed two classes of musician: those who performed in military ensembles on the battlefield and at ceremonial functions (razm), and those who performed at court festivities and banquets (bazm) and in the women’s quarters, the harem.

A cliff relief in Western Iran reflecting King Khosrow II Parviz’s love of music. This sixth-century monarch presided over a golden age of Persian classical music, and is here shown being escorted on a riverside hunt by a band of female harpists (detail below).

The periods of decline through which Persian music has passed have been mostly due to the withdrawal of court patronage. One of the most significant of these periods occurred during the Safavid dynasty, which ruled Iran from 1501 to 1722. This was when the foundations were laid for Iran’s future identity through the conversion of most of the population from Sunni to Shi’a Islam (which has since become the country’s official religion), and for the creation of a strong state within borders which are approximately those of today’s Iran. Art and architecture were at their height under the Safavids, but the new power of the religious authorities led to a decline in both music and musical scholarship. Yet the greatest Safavid ruler, Shah Abbās I (r. 1587–1629), was an ardent patron of visual art and music: he moved his capital from Qazvin to Isfahan, which became the centre for those arts; meanwhile music continued to be cultivated at the courts of Herat in the east and Gilan by the Caspian Sea. By the end of the Safavid period, the religious authorities’ enforcement of sharia law resulted in music, wine and dance being banned from all court and social gatherings. Many musicians migrated to India and Turkey, while others took refuge in the Sufi Khāneqāh, religious meeting places which became a channel for the preservation and diffusion of classical music. With Muslim musicians forbidden to practice their trade, Jewish and Armenian musicians came to dominate the profession.

The political instability of the eighteenth century was resolved when Agā Mohammad Shah (1742–97) established the Qajar dynasty (1785–1925), choosing Tehran as his capital. The Qajar era had great significance both for Iran’s modern history and for its music. Music flourished at the courts of Fateh ‘Ali Shah (r. 1798–1834) and Nāser al-Din Shah (r. 1848–96), and the diminished tradition of razm o bazm was restored: this was when leading musicians assembled the elements of the repertoire which constitutes the canon of Persian classical music today. Its codification is attributed to the court musician Mirzā Abdollāh (1845–1918), a prominent player and teacher of the setār lute; he and his brother, tār master Aqā Hoseyn Qoli (d. 1913), organised the music they had learned from their father, Ali Akbar Farhāni, and cousin Mirza Gholām Hossein, into a radif (row, or order) for the instruction of their pupils. The radif is the basis of modern Persian classical music with its extensive corpus of composition and improvisation, and with its function as teaching material.

Western music was introduced into Iran during the Qajar period, initially in association with military activities, as in Turkey and Egypt. During the reign of Naser al-Din Shah experts came from France to organise a military band for ceremonial events at court, and a music division was established in Dar al-Funun (Polytechnic School, the first modern school for boys, set up in 1851) to teach Western wind instruments and music theory. By the start of the twentieth century Iranian musicians were acquainted with Western staff notation, instrumentation and harmony, and the violin had become popular among players of the kamāncheh spike fiddle. The piano, being cumbersome and costly, was at first reserved for the nobility, and was taught by players of the santur hammered zither.

This painting by Kamal al-Molk in 1893 portrays the private ensemble of King Nasir al-Din Shah, himself a painter, poet and Westerniser, whose dictatorial style led to his assassination in 1896. The instruments being played are (from left to right) the zarb, tar, kamancheh and santur, and in the back row a dayereh.

The two most notable figures associated with this rising interest in Western music were Darvish Khān (1872–1926) and ‘Ali Naqi Vaziri (1886–1978), both virtuoso tār (long-necked lute) players with training in Western music theory. Darvish made some of the earliest recordings of Persian classical music in London, and is best known for adding a sixth string to the tar. Vaziri studied music in France and Germany, and in 1923 opened the first independent music conservatory in Tehran. He tried to modernise Persian music by using Western staff notation, harmony and performance contexts.

Musicians in the Qajar era were called ‘amale tarab (labourers for pleasure); classical musicians who performed for the king were called ‘amale tarab khāsse (special labourers for pleasure). Outside the court and aristocratic milieux, music was performed by urban entertainers (motrebs) who constituted a well-defined trade and were often Jewish or Armenian. Their basic ensemble consisted of players on the tar, the zarb goblet hand drum and the dāyereh frame drum with jingles, plus a dancer.

In contrast to the socially marginalised motrebs, ‘learned’ amateur musicians enjoyed high social status: there are many accounts of members of high society, doctors and scientists, who were also fine musicians, and who performed for small circles of connoisseurs. Yusef Forutan (1891–1978), an aristocratic setar master, typically refused to be photographed with his instrument in his hand, fearing that he might be taken for a motreb.7 It was thanks to Vaziri’s efforts to revive the traditional arts, coupled with government patronage and increasing contact with the West, that the status of classical musicians was gradually raised.

The beginning of the twentieth century was marked by a weakening of Qajar rule, intensive British and Russian influence, and the Constitutional Revolution of 1905–11 which transformed Iran’s polity, reducing the influence of kings and nobility as well as that of the religious authorities. Secular modernism was on the rise, inspired by Western ideologies of nationalism and liberalism. This period saw new methods of music teaching, the formation of professional orchestras with both Western and Persian instruments, and the advent of recording, which disseminated classical music more widely.

Following the Constitutional Revolution, Tehran’s first public concert of classical Persian music was organised by Anjoman-e Okhuvvat, a brotherhood association whose members came from prominent Iranian families; the event was held in a garden on the outskirts of Tehran to celebrate the birthday of the first imam of the Shi’a, ‘Ali ibn Abi Tāleb. Meanwhile Darvish Khan invited twenty leading musicians to form an orchestra under his direction, combining Persian and Western instruments. It became fashionable to give benefit concerts, with the education minister organising them for poor scholars and orphans, and with the war minister doing the same for starving Russians during the famine of 1921. Such concerts took place in open-air soirées, at garden parties and in Tehran’s Grand Hotel, where the first concerts with ticket sales opened to the public. But the audiences were mostly male, since before the reforms of 1936 Muslim women rarely appeared in public without the veil. With the introduction of Western-style theatres, public performance of classical music became the norm.

Both Persian and Western classical music, and hybrids of the two, continued to prosper after the Qajar era ended. In 1924 Reza Khān, commander-in-chief of the armed forces, seized power and, encouraged by the British, declared himself king the following year, thus inaugurating the Pahlavi dynasty. Inspired by his neighbouring contemporary Mustafa Kemal Atatürk (1881–1938) in the recently-established Republic of Turkey, Reza Shah imposed many political, cultural and social reforms to modernise the country. His support for women’s rights was both notable and controversial: he banned the chador in favour of Western dress, and encouraged the integration of women into public life; the classical singer Qamar al Moluk Vaziri (1905–59) was amongst the first women to benefit from these reforms. On succeeding his father in 1941, Mohammad Rezā Shah (1919–80) continued his efforts to modernise Iranian society.

After its introduction to Iran in 1940, radio became an important source of musical patronage. One of the most prominent figures associated with Radio Iran was Ruhollāh Khāleqi (1906–65), a prolific writer and champion of Persian classical music who arranged its traditional forms for orchestra. In 1944 he founded the Society for National Music, which was the precursor for the Conservatory for National Music (Honarestān-e Musiqi-ye Melli), created in 1949 under the aegis of the education ministry. The primary objective of these institutions was to support native traditions, and to revive interest in Iranian instruments, which had become less popular than Western ones. Even so, the violin, clarinet and piano (used widely in Persian music by this time) were also taught as part of the conservatory curriculum.

During the last two decades of Mohammad Reza Shah’s reign the pace of Westernization became even more rapid. The educated class was infatuated with Western music, classical as much as popular, in part because of its ‘superior’ associations, while those who preferred classical Persian music were regarded as behind the times and opposed to change.8 This debate reflected the larger crisis in Iranian national identity.

In 1961, UNESCO sponsored an International Congress in Tehran, entitled ‘The preservation of traditional forms of the learned and popular music of the Orient and the Occident’. At issue was the growing trend towards musical Westernisation in both Iran and neighbouring countries, and the question of how to control it; in 1962 the influential writer Jalāl Al-e Ahmad (d. 1965) compared the Iranians’ obsession with the West to a disease.9 The ‘hybridisation’ and ‘vulgarisation’ of Persian classical music became the subject of intensive debate, with the musicologist Bruno Nettl reporting that in Tehran in the late 1960s classical music in its ‘serious and complex’ style was only practiced by a very few musicians, while a lighter and more rhythmic style was taking over as a result of Western influence.10

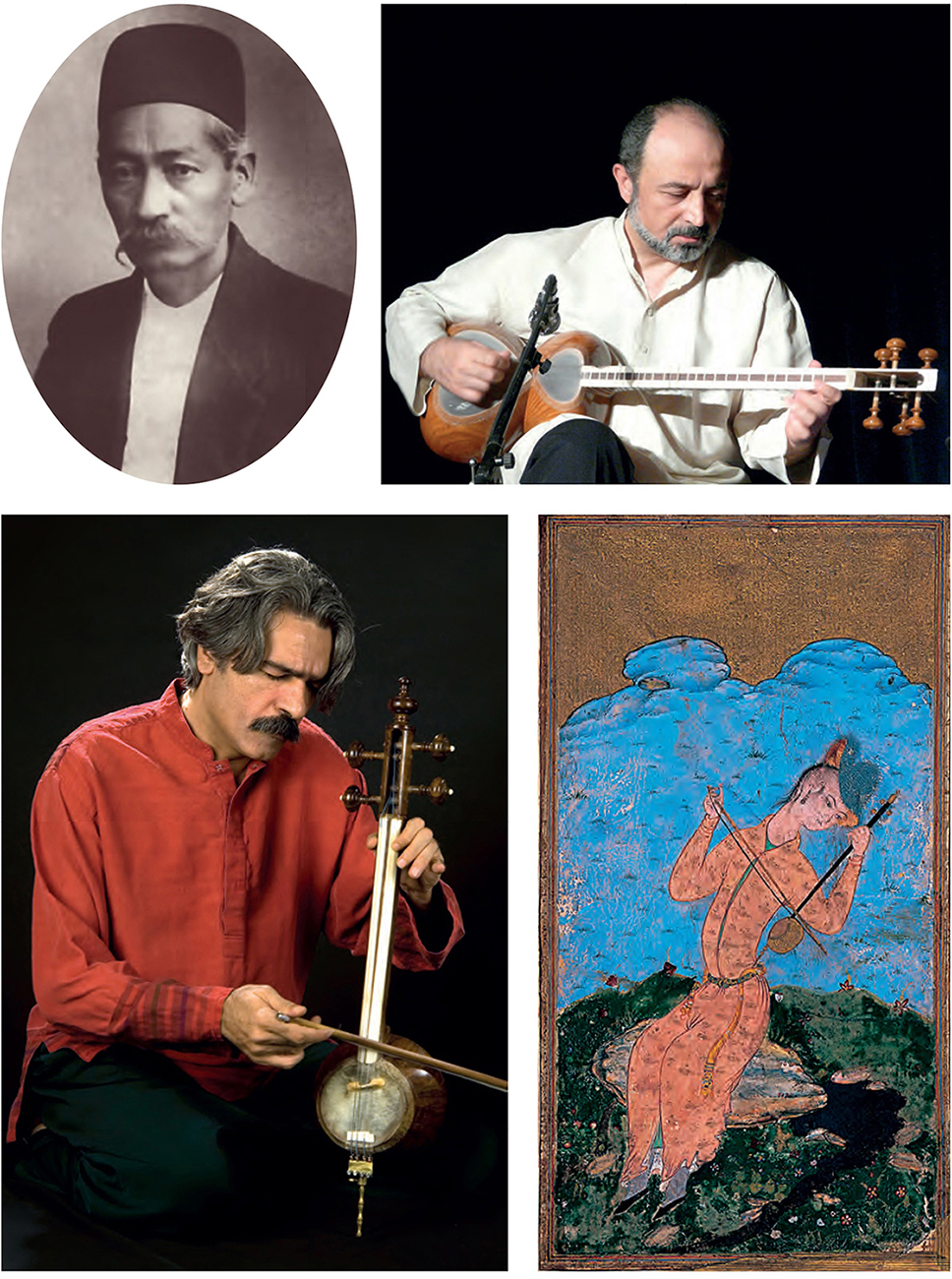

Despite his blindness, Nur ‘Ali Borumand became the twentieth century’s leading teacher of Persian classical music, as well as one of its most celebrated exponents.

At this point both the Iranian Ministry of Culture and State Radio and Television began actively sponsoring classical Persian music in an attempt to preserve it, and in 1965 the music department of the fine arts faculty at Tehran University began teaching a course on its theory and practice. There Nur ‘Ali Borumand, one of its most influential authorities, taught the radif repertoire to leading contemporary musicians. In 1970, spurred by Borumand, the Centre for the Conservation and Diffusion of Music was created under the aegis of state television. This brought together the best musicians of the day, including the singer ‘Abdollah Davāmi (1891–1980), the tar player ‘Ali Akbar Shahnāzi (1897–1985), the setār player Yusef Forutan (1891–1978) and the kamancheh player ‘Asqar Bahāri (1905–1995). Thus was Persian classical music transmitted and preserved during the 1970s. Many of today’s classical masters – including the tar and setar players Dāriush Talā’i (b. 1953), Mohammad Rezā Lotfi (1947–2014) and Hossein ‘Alizādeh (b. 1951), and the singers Mohammad Rezā Shajariān (b. 1940) and Parisā (b. 1950) – studied at the Centre, and became teachers themselves.

Recordings and publications by these musicians were sponsored by both broadcasters and the ministry, and festivals were held to highlight their music, most notably the Shiraz Art Festival, which also featured performances by traditional musicians from India, Vietnam, Indonesia, Japan and Egypt in concerts in the Hāfezieh. Studies of Persian classical music – by both Iranian and foreign scholars – proliferated.

The revolution of 1978–9, which forced Mohammad Reza Shah into exile, was initially a political reaction against the authoritarianism of a regime that was perceived as subservient to Western hegemony, principally by the United States. It was a multi-party and multi-ideological revolution, and many classical musicians participated by composing and performing revolutionary songs.

The first decade of the Islamic Republic, which established a conservative theocracy, was marked by eight years of war with Iraq and by stringent new regulations on behaviour, including the segregation of the sexes in public, the introduction of new dress codes, the closing of theatres and cinemas and the banning of music in public and in the media; revolutionary songs sung by men were for a while the only music permitted to be broadcast, and women were banned from singing and dancing for audiences which included men. Many forms of music were affected; Iranian and Western popular music were deemed arousing and vulgar, and female pop singers such as Googoosh (b. 1950) were either silenced or left the country. But although musical institutions were officially closed, music continued to be performed and taught privately and the number of people willing to learn Persian classical music increased greatly, along with a growth in domestic music-making. Popular Iranian music went underground, resurfacing in diaspora communities such as the large one in Los Angeles.

The end of the Iran-Iraq War in 1988 and the death of Ayatollāh Khomeini a year later led to a relaxation of restrictions on musical performance. At the end of his life, Khomeini had issued a fatwa authorising the buying and selling of instruments, and permission for specific concerts was occasionally granted, with a recital by Mohammad Reza Shajarian to celebrate the end of the war being a significant event. Six performances were scheduled to take place in Tehran’s most prestigious opera house, but because the unexpected demand far exceeded the space available, the hall’s security department cancelled the last three concerts.11 In 1989 Hossein Alizadeh founded ‘Hamāvāyān‘ (‘singing together’), an ensemble which included a chorus of male and female singers, and performers on Persian classical instruments: ‘I wanted to reintroduce women’s voices in public’, he explained.12 While solo female singing is still prohibited to male audiences, choral singing is permitted, under the rationale that individual women’s voices are hard to identify.13

Perhaps the most important musical event at this time was the re-opening of the music department at Tehran University in 1989, after a decade of closure. In September 1992, Ayatollah Khamene’i, then Guide of the Republic, launched a campaign against ‘cultural aggression from the West’ which conferred a certain legitimacy on Iranian music, both classical and of different ethnic groups, this being regarded as an affirmation of national identity. A revival of interest in classical music was one by-product of the continuing ban on popular music during the 1990s, as restrictions on its performance eased and the output of classical cassettes and CDs increased dramatically.14

Yet public performances and recordings continued to be closely monitored by the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance (known by its abbreviated title, Ershad, ‘guidance’). All planned concerts had to be submitted for preliminary censorship with regard to the type of music and the content of the lyrics, which ‘should not include words which might offend social and religious dignity’; this mirrored a similar censorship in literature, where a few ‘un-Islamic’ words could be deemed – and still are at the time of writing – sufficient to disqualify a book from publication. Classical musicians objected to this; as a result the most prominent among them were exempted from Ershad authorisation, but most chose to perform abroad because of the ever-present threat of arbitrary, last-minute cancellations. Over the past two decades, in order to display Iran’s cultural heritage, both the Ministry of Culture and the Islamic Propaganda Organisation have sponsored festivals of Persian classical and Iranian regional music, the most important being the Fajr (‘dawn’) festival which marks the anniversary of the revolution. Classical masters rarely attend these events, regarding them as propaganda tools of the government.

In 1997 the landslide election of President Mohammad Khātami, who was seen as a reformer, led to cultural policies reflecting a slightly more liberal turn. Certain forms of popular music were permitted, as were public performances by women (though only for all-women audiences). However, since the election of President Mahmud Ahmadinejād in 2005 there has been a return to stricter censorship, and obtaining a permit to publish books or recordings or to give a performance has become much more difficult. Despite this, Persian classical music continues to be taught in universities, cultural centres and private institutions – of which there are more than a hundred in Tehran, supported by individual patrons – and by masters who teach and perform in private homes.

It should be remembered, however, that until the twentieth century most classical music was performed in private gatherings – for small circles of connoisseurs, at Sufi brotherhoods, for family and friends, or in festivities including poetry recitation: the public concert was essentially a Western phenomenon. Moreover, apart from military music, public musical performance took place mostly in the context of religious and ceremonial rituals which are not considered ‘musical’ per se: these include events in zurkhāneh (Iran’s traditional fitness-clubs), the recitation of the Qur’an (tajwid), the call to prayer (‘azān), the recitation of the national epic Shāhnāmeh (naqqāli), the Shi’a Passion play (ta’zieh) and the singing of laments (rowzeh-khāni); ta’zieh and rowzeh-khani both commemorate the martyrdom of the Shi’a Imam Hossein and his family in the battle of Karbelā in 680. Such ceremonies require singers skilled in classical music, and they have been crucial supports for classical music during its periods of decline and discrimination. And in Iran, as in many parts of the Middle East, classical singers have traditionally honed their skills in the call to prayer and the recitation of the Qur’an; many celebrated singers from the first half of the twentieth century sang in the ceremonial mourning rites mentioned above. Mohammad Reza Shajaryan was a noted qāri (reciter of the Qur’an) before gaining fame as a classical performer.

Bārbad, minstrel-poet of the Sassanian king K_osrow II Parviz, is thought to have helped establish the modal model that developed into the system forming the basis for Persian classical music today. He is said to have created seven ‘royal modes’ (Khosrowani), thirty derived modes and 360 melodies, corresponding to the number of days respectively in a week, month and year. The nature of these compositions is unknown, but some of their names survived into the Islamic period thanks to Persian poets and scholarly writing in Arabic. This was when the great theorists of the ‘science’ of music – led by Al-Farabi – turned music into an aspect of mathematical philosophy, attaching specific meaning to intervals, modes, scales and rhythmic cycles. While the language of scholarship was mainly Arabic, from the thirteenth century onwards important Persian works were written on the subject by scholars such as Qoṭb-al-Din of Shirāz and Qader Maraqi. The former is said to have been the first to use the word maqām as a general term for mode, and to have given an important account of the modal system. Although the character and names of the modes changed, the notion of seven modes and their association with stars and nature has survived, as has the idea of the principal modes having a number of subsidiary melodic components, often associated with places and other external associations.

Poet-singers enjoyed the same high status as scribes, physicians and astronomers in the Sassanid dynasty (224–651). Inset detail, lower left: Court minstrel Barbad plays the lute, a barbat, for Khosrow II Parviz.

After a period of relative decline in musical scholarship during the Safavid dynasty, leading musicians made a deliberate attempt to conserve and codify their vanishing heritage. Thus did two celebrated musical brothers – setar-master and court musician Mirza Abdollāh and tar-master Aqa Hoseyn Qoli – come to crystallise the classical canon as it is now performed. It is based on seven primary modes called dastgāh, and five secondary modes called āvāz. Each dastgah or avaz is comprised of short units or melody-types called gusheh (‘corner’); a series of gusheh arranged in a fixed order is called a radif. The radif provides the framework for improvisation and composition, and is the central resource for sung Persian poetry. The closest relative to this system is the Azerbaijani muğam. In Borumand’s words, ‘The radif is the principal emblem, the heart of Persian music.’ There are between two and three hundred gusheh in this essentially solo repertoire.

While each musician and teacher has his own version of the radif (usually referenced by his name), the radifs have much in common. Each dastgah in the radif has its particular pitch-set, or scale, its unique configuration of intervals, and its hierarchy of scale degrees. The intervals used include the whole and half-tones common to the Western tuning system, as well as the three-quarter and five-quarter tones characteristic of much Middle Eastern music

Each dastgah provides the basis on which its associated gusheh melodies are composed; it dictates not only the pitches but also the relative importance of specific pitches. Most significant of these are the shahed (‘witness’), which acts as the tonal centre around which the melody evolves; the ist (‘stop’), a temporary stopping-note; the moteghayer (‘changeable’), which is a variable pitch; the āqāz (‘initial’) and the forud (cadential descent). Gusheh melodies are composed in accordance with these and other guiding principles relating to rhythm, improvisation and sentiment.

Gusheh may be named after places, ethnic groups, situations, emotional states and types of poem; each has its own character in terms of modal structure and melodic or rhythmic pattern. Many gusheh have an ambitus of no more than a fourth or fifth. Some have particular importance, such as darāmad (‘coming out’, introduction), which is usually the first gusheh performed in a dastgah or avaz, and whose principal motif acts as a theme for the whole performance. Some dastgah have more than one daramad. Most gusheh are from thirty seconds to six minutes in length; they are usually strung together in gradually ascending order of pitch before returning to the opening pitch at the end; most involve singing, though some are purely instrumental. And while an instrumental radif may include up to three hundred gusheh, vocal ones have fewer, although as they are continually evolving, new gusheh can always be added. The choice of mode, or dastgah, is dependent on the mood of both the musician and his audience, as each mode is considered to have its own character – meditative, majestic, cheerful, tragic or melancholic. Musicians use the term hāl to describe the mood and ethos of an event, but the word also denotes the mystical state essential to all creation of musical beauty.

As a corpus of pedagogical material the radif is transmitted orally, and the process can take years: once ‘internalised’ (as the tar and setar master Dariush Tala’i puts it), the radif becomes the basis for improvisation and composition: the process ‘goes beyond apprenticeship and has to become a state of mind’.15 As most gusheh have vocal origins and are built on poetic metres, the student also learns verses appropriate to each. Notated and published versions of radif first appeared in the early twentieth century, although master musicians still prefer to teach orally. But oral transmission was not always straightforward: Mirza Abdollah and Aqa Hoseyn Qoli sometimes had to hide behind a door to overhear and learn melodies which their teacher had refused to impart to them. In the twentieth century, recordings and the radio became an additional tutelary source.

But melody is only one focus: rhythm is the other. Over time, the complex repertoire of rhythmic cycles attested to in the medieval treatises has been abandoned and reduced to shorter cycles. The rhythm of Persian classical music has often been described as free or unmetred. However, the rhythmical structure of the melody in the improvised sections (which are known as avaz, and are not to be confused with the avaz modes in the radif) is guided by the metrical structure of the verse – the ‘aruz system of Arabo-Persian versification, with its fixed arrangement of long and short syllables.

In the avaz section, the singer usually chooses a different gusheh for each line of the poem, which is usually a ghazal – a poetic form with rhyming couplets and a refrain in the same metre. Meanwhile a melodic instrument follows, imitates or improvises a response to the singer’s phrases. These exchanges between singer and instrumentalist are called sāz o avaz (‘instrument and singing’) and are considered to be the most engaging part of the performance. A performer usually improvises within the limits of a particular dastgah, but may also modulate from one dastgah into another.16 A solo instrumentalist can also perform avaz, sometimes accompanied by a drummer.

A singer’s skill may be measured by his or her choice of the appropriate poem for the appropriate dastgah to fit the occasion and the mood of the audience; clarity of diction is considered essential. Ornamentation is another important facet of Persian classical music: Iranian singers have developed an elaborately ornamented style called tahrir which sounds like a fast, flexible yodelling – a passage of many notes performed on just one syllable of text which is added at the end of each half-line of verse.

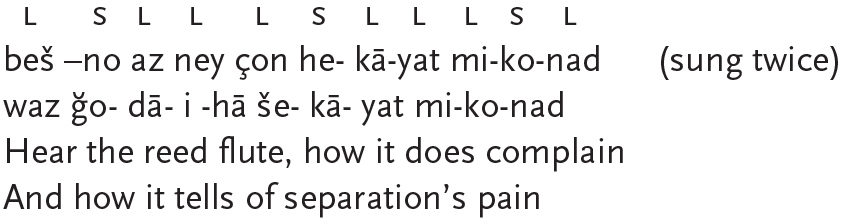

EX. 14.1 The opening line of Rumi’s ‘Masnavi’ as sung by the late Mahmud Karimi (1927–84) in Navā, which is one of the principal dastgahs in the gusheh of Shah Khatā’ī; transcribed by the Iranian ethnomusicologist Mohammad Taqi Masʼudiye (1927–98). The rhyming couplet is composed of two hemistichs of eleven syllables, each in one of the variants of ramal meter in fixed arrangement of long (L) and short (S) syllables in this scheme: LSLL/LSLL/LSL. As is evident, the vocal rhythm is a reflection of the poetic metre.

The saz o avaz sections are introduced, interrupted and concluded by pre-composed pieces with a steady beat, in regular groups of two, three or four beats. There are four types of pre-composed piece: pishdaramad, chaharmezrab and reng (all instrumental), and tasnif (vocal); these are largely of twentieth-century origin, with known composers. The pishdaramad (pre-introduction) is played heterophonically by an instrumental ensemble; chaharmezrab (‘four beats’) is a fast virtuoso piece, with a repeated rhythmic pattern usually played by a soloist. A reng is a rapid dance in 6/8 metre which usually marks the conclusion of a dastgah. A tasnif is a metric song with instrumental accompaniment, whose lyrics need not be drawn from classical poetry but can also be topical: tasnif have often addressed political and social issues such as women’s rights and religious and political autocracy. Among the most eminent exponents of this genre were the poet-musicians Abol Qāsem ‘Āref Qazvini (1882–1934), ‘Ali Akbar Sheydā (1844–1906) and the poet Malek al-Sho’arā Bahār (d. 1951). Their tasnif remain key elements of the classical repertoire today.

A complete performance of Persian classical music is expected to include pishdaramad, chaharmezrab, avaz, tasnif and reng, all deployed with a certain flexibility. This is analogous to the compound suites found elsewhere in the Middle East, as with the Iraqi maqām or the nawba of North Africa.17 At an informal gathering the improvised avaz can last over half an hour, followed by one or more tasnif, but in concerts and on radio these are usually limited to ten or fifteen minutes.

Borumand was taught by Darvish Khan (top left) and himself taught tar-maestro Dariush Tala’i (top right). Below left: the kamancheh in the hands of Kayhan Kalhor, one of its leading present-day exponents, and, below right, as played in this sixteenth-century miniature: Young musician. Qazvin, Iran, about 1580.

(Paper, ink, opaque watercolour, gold. 34.4 ・× 23.7 cm.)

The most typical classical performance configuration consists of a male or female singer accompanied by one or more instruments, as depicted in Persian miniature paintings from the thirteenth century onwards. The principal instruments are the two long-necked lutes, tar and setar; the trapezoidal santur hammered zither; the kamancheh spike fiddle; the ney reed flute; and the goblet-shaped zarb drum. Other instruments such as the ud (a short-necked lute), the daf and dāyereh (frame drums) and the qānun (a plucked dulcimer) are also found.

The tar and setar are the instruments most closely identified with Persian classical music. The tar is descended from the ancient rabāb, and was developed in Iran towards the end of the eighteenth century. Its double-bowled body is shaped like a figure eight, and its ultra-thin lambskin membrane creates a brilliant sonority. The body is of mulberry with a maple or walnut neck; the twenty-five moveable frets are of gut. The six metal strings in three courses are plucked with a metal plectrum. The setar’s more refined and intimate sound is considered to be well suited for women. Smaller than the tar and with a single-bowl shape, it has the same number of frets; to its three strings (‘seh’) a fourth is added for resonance; it is plucked with the long nail of the forefinger.

The santur, a trapezoidal zither or dulcimer, is made of a hard wood such as walnut; the two mallets (mezrābs) are light and pliable, and typically padded with felt. There are two rows of nine bridges (kharak), each holding a course of four strings for a total of seventy-two strings, which are anchored to the left of the instrument and strung across the face to tuning pegs on the right side.

The kamancheh is a spike fiddle with a bowl-shaped resonator of gourd or wood and four melodic strings. The face of the resonator is covered with a thin lamb-skin or fish-skin membrane; the fretless neck passes through the body to create a spike at the bottom, with the instrument held on the player’s knee and played with a horsehair bow. This is loosely strung, to allow variation in tension when pulled across the strings; the musician rotates the instrument as it is played, keeping the bow on a relatively stable plane.

The ney end-blown reed flute is common throughout the Middle East, and in thirteenth-century Persia it became the principal instrument for the dervish dancers’ mystical gatherings. In the Persian classical style it is finely nuanced, reflecting the human voice in its lower register and delicately imitating birdsong at the top. There are five finger-holes and a thumb-hole on the back; the blowing end is wrapped in metal, with a sharply bevelled edge on its interior; the length varies depending on the pitches required, and performers come on stage with a set of instruments.

The zarb (also called the tombak, tonbak or dombak) is a goblet-shaped drum, and has been the primary percussion instrument since the early nineteenth century; it is larger than most such drums in the Middle East. Modern instruments may have synthetic skins, but traditional ones have a thicker skin of camel or calf. The prominent master of the zarb, Hossein Tehrani (1911–73), is celebrated for having introduced new rhythmic techniques in zarb performance, raising it to the status of a solo instrument.

Among classical musicians in contemporary Iran, the clash of authenticity versus innovation is the subject of ongoing debate. Those who innovate within the framework of tradition are called now āvarān-e sonnati (‘bringing newness to tradition’); one of the most prominent in this group is the composer and performer Hossein Alizadeh. Like many other musicians, he believes that the radif is still most suited to Persian classical poetry, but that new melodic and rhythmic models are needed for modern poetry. Many musicians have found new modes of expression by incorporating elements of regional styles, and through collaboration with classical musicians of other cultures. Those of the kamancheh player Kayhan Kalhor (b. 1963) reflect collaboration with the traditions of North India, Turkey and – with the Kronos Quartet – Europe.

One of today’s most popular singers of Persian classical music is Parisa (b. 1950), here seen performing beneath a back-projection of her own image.

Traditional ensembles are now often expanded through new polyphonic arrangements, with the addition of instruments either borrowed from other traditions (Afghan rabāb or Baluchi sorud) or newly invented, such as the saghar, a long-necked lute designed and made by the vocalist Mohammad Reza Shajarian. The daf frame drum, once Iran’s principal rhythmic instrument and the main instrument of Kurdish dervishes, has been reintegrated into traditional ensembles. Tempos have generally become faster. The prohibition on women singing solo for male audiences persists, but all-female ensembles have become more prominent, and women have also taken on a greater role as instrumentalists, including in mixed-sex ensembles, playing all kinds of instruments – Iranian classical and regional as well as Western. Amateurs have tended to give way to professionals, and the status of classical music has been raised as a result.

All this means that musical life in contemporary Iran is thriving, whether classical or semi-classical, fusion, regional, rock, pop or jazz, whether authorised or not. Persian classical music and its associated theory is taught both in universities and privately, supported by many publications by Iranian scholars and musicians. Most of the repertoire of the great masters of the past has been published with notation and released on cassettes and CDs. Private homes remain an important venue, as when concerts are held in public they still need a permit from Ershad. The control – and prohibition – of musical performance remains a live issue.

In 2009 UNESCO honoured the Persian radif as part of the ‘intangible cultural heritage of humanity’, and while it is now sustained in Iran through government and private patronage, it is also passionately supported by the musical diaspora in Europe and in the United States, most notably in Los Angeles. Moreover, Persian classical music is also finding a growing international audience thanks to the ‘world music’ boom. Meanwhile, many Iranians feel it important to affirm this positive aspect of their culture, to counteract other facets of their country’s international image. In short, Persian classical music is full of contemporary significance, and remains an enduring, living tradition.

Further Reading

An overview of the history and the practice of Persian classical music with a good section on instruments is Jean During, Zia Mirabdolbaghi and Dariush Safvat’s . For more technical detail on the theory of Persian music see Hormoz Farhat’s and the chapters by Margaret Caton and Dariush Tala’i in vol. 6, . In the same volume Stephen Blum gives an excellent introduction on musical practices in Iran. For a pedagogical presentation of with notation and sound recording see Tala’I’s . Good articles on instruments, musicians and musical terms are to be found in , available online (www.iranicaonline.org). More emphasis on vocal repertoire is provided by Owen Wright’s and Rob Simms and Amitr Koushkani’s studies ofMohammad Reza Shajarian and the art of avaz.

Recommended listening

Faramarz Payvar Ensemble, , Elektra, LC 0286, 1991 (originally released in 1974).

Iman Vaziri Parissa and Ali Rahimi, . Cologne Music, 2007.

Mohammad Reza Shajarian, Hossein Alizadeh, Kayhan Kalhor and Homayoun Shajarian,(2 CDs), World Music Institute 468023, 2003.

Hossein Alizadeh and Madjid Khaladj,, Buda 3259119860822, 2000.

Mahmud Karimi, , Mahoor Institute of Culture and Art, M.CD128, 2003.

The Mahoor Institute of Cultural Art (www.mahoor.com) is an excellent source for recordings of both Persian classical music and Iranian regional traditions.