Few men have changed the way England looks today more comprehensively and with less acknowledgement than John Tradescant the Elder (c. 1570–1638), gardener to the Duke of Buckingham and founder of what became known as Tradescant’s Ark. His legacy lives on in parks and country lanes, in gardens and in city squares: the horse chestnut, lilac, plane trees, larch, acacia, tulip trees and Virginia Creeper were all imported first by this indefatigable horticulturist, traveller and collector.

Tradescant’s first employment was as gardener to Lord Robert Cecil at Hatfield House, where he not only planned the gardens, but also stocked them with plants gathered on his journeys to various European cities. As if this were not enough, he was also required to do odd jobs such as ‘setting a pair of soles upon your Lordship’s pompes’, as his accounts reveal.1 Indeed, even his employer seems to have felt pity for him at times. One entry in the household book reads: ‘To John Tradescant the poor fellow that goeth to London 2s 6d.’

Cecil, Privy Councellor, Secretary of State and Lord Treasurer, was one of the most powerful men of his age. His prestige and immense fortune were mirrored in those of his house and park, which he acquired in 1607 and enlarged to reflect his status. Tradescant himself was sent to the Low Countries in order to procure more plants and set out in 1611, in his pocket six pounds in cash and a small fortune in bills of exchange. He sent back rare plants by the hundred (one shipment contained, among many flowers, fruit trees and other plants, 800 tulip roots, another 400 lime tree saplings), running up enormous costs, which were paid, apparently without demur, by His Lordship.

The European tour was not exclusively devoted to the purchase of plants. From the Low Countries Tradescant travelled on to Rouen, where he bought an ‘artyfyshall byrd’ for his master. It is quite possible that he visited some of the collections in Amsterdam and in Leiden, where the university had not only a hortus botanicus (‘botanical garden’), but also the famous theatrum anatomicum (‘anatomical theatre’), which later flourished into a fully-fledged cabinet of curiosities and university museum. In addition to seeing the botanical gardens and indoor collections he is unlikely to have missed the opportunity to visit some of France’s famous parkscapes. Eventually Tradescant had to return to Hatfield, chalking up on the ferry from Gravesend to London one shilling ‘to the boyes of the ship to be Carefull of the trees’.

While the garden at Hatfield was rapidly becoming one of the richest and most beautiful in England, the king himself, James I, took great interest in another of Tradescant’s discoveries brought to his attention by his faithful Lord Cecil: among the plants imported from Rouen were mulberries, which, it struck the monarch, might be the beginning of a very profitable line in silk production. The Secretary of State, incidentally, had a patent on the importation of the trees and promised not to take more than a penny per plant, of which more than a million were to be imported every year. The scheme, which would have paid Cecil amply for his generosity towards his gardener, came to nothing, but to this day many of England’s older gardens still contain ancient mulberry trees as silent witnesses to the ingenious but stillborn plan.

The double responsibility of Secretary of State and Lord Treasurer proved too much for the fragile constitution of Tradescant’s master, and in early 1611 the ‘crook-backed earl’, then forty-eight, found his health collapsing under the strain of his duties. A laconic entry in the Tradescant’s Hatfield accounts for April that year tells the remainder of the story: ‘for mowing of the Coorts and East Gardyn against the funerall 4s’. Robert Cecil, Earl of Essenden, never saw the completion of his garden or his house.

Tradescant was passed on to William Lord Salisbury, his former employer’s son, and continued working at Hatfield and the other estates inherited by his new master, but in 1615 he accepted the employ of Lord Wotton at Canterbury, in whose service he went to Russia as botanist to a diplomatic party. He kept a journal during this expedition, in which he recorded not only the course of the journey (‘being Inglishe and strangers 7 sayls bound for Archangell’), but also the customs and of course the plants of his Russian hosts, remarking among other things: ‘For ther streets they be paved with goodli timber trees, cleft in the midell, for they have not the use of sawing in the land, spedtiali in that part whear I was, neyther the use of planing with the plane, but onlie with the shave,’ an image still vivid in the great Russian novels of the nineteenth century. On leaving Archangel the English party fired a salute with their ships’ cannon, thanking their hosts for the hospitality they had received. One of the cannon was unfortunately loaded and ripped a large hole in a harbourside house, leaving the hosts ‘gaping and in great perplexity’.

Tradescant, unfaltering plant collector that he was, found botanical specimens to bring back to England. In addition, a second interest now gripped him. Years later, his son published the Musaeum Tradescantianum (1656), which contains entries to remind us of his father’s expedition: ‘A Russian vest; Boots from Russia; Boots from Muscovy; Duke of Muscovy’s vest wrought with gold upon the breast and arms; Shoes from Russia shod with iron; Shoes to walk on snow without sinking; Russian stockings without heels; Boots from Lapland.’ Tradescant’s interests were no longer confined to plants or to observing the living arrangements of other countries: he had become a collector of foreign rarities, and while the living specimens were tended to in the gardens and greenhouses under his care, the other objects became part of an ever-growing collection of curiosities, which, in time, would make his name just as much as his horticultural skills.

While John Tradescant laboured in gardens and on foreign expeditions, his son, John the Younger, was attending the King’s School, Canterbury, where he received an education superior to his father’s, and was already helping with his work. The boy cannot have seen much of him, as the elder Tradescant was enlisted in 1620 on a mission to hunt down the Corsairs of Barbary, Algerian pirates threatening the trade routes of the Mediterranean. This sudden enthusiasm for naval warfare was not as dramatic a career change for the gardener as it may seem, for he was drawn to volunteer not by the promise of battle and the spoils of war, but by accounts of a wonderful golden apricot that was to be found in Algiers. There might be a war on, he decided, but the opportunity of bringing back a rare and delicate fruit was simply too good to miss.

From the horticultural point of view (not a perspective taken, incidentally, by the captain of the vessel, who was sceptical about taking this expert on European flora on combat duty) the journey was a resounding success. The captain’s collection, too, was swelled by Tradescant’s unscheduled exploits. He was able to bring back plants and artefacts from Portugal, Spain, the southern coast of France, Rome, Naples, the Greek Islands and Constantinople (where he picked up lilac) before even reaching Algiers, and from Mount Carmel, Damascus, Alexandria, Crete and Malta on the way back. The later Musaeum Tradescantianum lists, in the orthographically more orthodox spelling of John the Younger: ‘Barbary Spurres pointed sharp like a Bodkin, A Moores Cap, A Portugall habit, 2 Roman Urnes, An Arabian vest, and Divers sorts of Egges from Turkie: one given for a Dragons Egge.’

John Tradescant the Elder had made a great reputation for himself and it is hardly surprising that he was snapped up by another man who had made his own fortune: George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, the royal favourite who had charmed himself from a relatively humble background into the high nobility and a position of great power. For the horticulturist and his son, Buckingham’s gardens were a new challenge: whole avenues had to be planted and plants imported on a lavish scale from overseas. Indeed, trees and flowers were not His Lordship’s only pleasure. On 31 July 1625, John Tradescant wrote to Edward Nicholas, Secretary to the Admiralty:

Noble Sir

I have Bin Comanded By My Lord to Let Yr Worshipe Understand that It Is H[is] Graces Plesure that you should In His Name Deall with All Marchants from All Places But Espetially the Virgine & Bermewde & Newfownd Land Men that when they Into those Parts that they will take Care to furnishe His Grace Withe all maner of Beasts & fowells and Birds Alyve or If Not Withe Heads Horns Beaks Clawes Skins Gethers Slipes or Seeds Plants Trees or Shrubs Also from Gine or Binne or Senego Turkye Espetially to Sir Thomas Rowe Who is Leger At Constantinoble Also to Captain Northe to the New Plantation towards the Amasonians With All thes fore Resyted Rarityes & Also from the East Indes Withe Shells Stones Bones Egge-shells With what Cannot Com Alive My Lord having heard of the Dewke of Sheveres & Partlie seene of His Strang Fowlls Also from hollond of Storks A payre or two of yong ons Withe Divers kinds of Ruffes Whiche they theare Call Campanies this Having Mad Bould to present My Lords Comand I Desire Yr fortherance. Yr Asured Servant to Be Comanded til he is John Tradescant

Newhall this 31 of July 1625

To the Marchants of the Ginne Company & the Couldcost Mr. Humfrie Slainy Captain Crispe & Mr. Clobery & Mr. John Wood cape marchant.

The things Desyred from those parts Be theese in primis on Ellophants head with the teeth In it very larg

on River horsses head of the Bigest kind that can be gotten on Seacowes head of the bigest that Can be Gotten on Seabulles head withe hornes of All ther strang sorts of fowelles & Birds Skines and Beakes Leggs & phetheres that be Rare or Not knowne to us

of All sorts of strng fishes skines or those parts the Greatest sorts of shellfishes shelles of Great flying fishes & sucking fishes withe what Els strang of the habits weapons & Instruments of ther Ivory Long fluts of All sorts of Serpents and snakes Skines & Espetially of that sort that hathe a Combe on his head Lyke a Cock

of All sorts of ther fruts Dried As ther tree Beanes Littill Red & Black In their Cods whithe what flower & seed Can be Gotten the flowers Layd Betwin paper leaves In a Book Dried

of All sorts of Shining Stones or of Any Strang Shapes

Any thing that Is strang2

Any thing that Is strang. It may be assumed that Buckingham had seen Tradescant’s already considerable collection of curiosities and liked what he saw. He was in the process of furnishing a house at Newhall and was looking for interesting objects to join the works by Michelangelo, da Vinci, Holbein, Raphael and Rubens, the antiquities and other precious pieces already in his possession. Tradescant was to be his agent, or one of them, as Buckingham had several scouring the world for treasures. The ducal director of gardens was by now living in South Lambeth, a relatively convenient place from which to keep an eye on his employer’s various properties, and for keeping in touch with ships docking in London bringing new and exotic items into the country.

Buckingham’s star was at its zenith. It was to plummet even faster than it had risen. On his way back to London in 1627, after a bungled effort to relieve the Huguenots at La Rochelle, the formerly English port on the French mainland reoccupied by France, he was assassinated. Tradescant, once again without an employer, quickly found himself appointed to his most prestigious post yet as Keeper of His Majesty’s Gardens, Vines and Silkworms at Oatlands in Surrey, twenty miles from his home. While administering the royal gardens the Tradescants proceeded to order their own collection, to breed and classify the plants they had, and set forth on their great enterprise whose very name testified to their ambition: Tradescant’s Ark.

This museum was to become famous all over Europe; later no educated traveller would visit London without knocking at its door. One of these pilgrims, a merchant captain by the name of Peter Mundy, recorded his impressions after a visit in 1636:

Having Cleired with the Honourable East India Company, whose servant I was, I prepared to goe downe to my friends in the Countrey … In the meane tyme I was invited by Mr. Thomas Barlowe (whoe went into India with my Lord of Denbigh and returned with us on the Mary) to view some rarities att John Tredescans, soe went with him and one friend more, there wee spent the whole day in peruseings and that superficially, such as hee had gathered together, as beasts, fowle, fishes, serpents, wormes (reall, although dead and dryed), pretious stones and other Armes, Coines, shells, fethers, etts. Of sundrey Nations, Countries, forme, Colours; also diverse Curiosities in Carvinge, painteinge, etts., as 80 faces carved on a Cherry stone, Pictures to bee seene by a Celinder which otherwise appeare like confused blotts, Medals of Sondrey sorts, etts. Moreover a little garden with divers outlandish herbes and flowers, whereof some that I had not seene elsewhere but in India, being supplyed by Noblemen, Gentlemen, Sea Commaunders, etts. With such Toyes as they could bring or procure from other parts. Soe that I am almost perswaded a Man might in one day behold and collecte into one place more Curiosities than hee should see if hee spent all his life in Travell.3

Mundy, incidentally, took the time to visit other sights in London, among which was a ‘unicorn’s horn’ on exhibition in the Tower of London. While the Ark in Lambeth could, like its biblical antecedent, boast ‘beasts, fowle, fishes, serpents’ and ‘wormes’, unicorns were the pick of the desirable creatures and among the first of all objects of curiosity. In his History of Four-Footed Beasts, Edward Topsell described its curious habits: ‘It is sayd that Unicorns above all other creatures, doe reverence Virgines and young Maides, and that many times at the sight of them they growe tame, and come and sleepe beside them, for there is in their nature a certaine savor, wherewithall the Unicornes are allured and delighted.’4 Tradescant, aware of the fact that he was lacking a unicorn’s horn for his collection, managed to get his hands on one himself, even though he catalogued it, with a confusion characteristic for his time, as Unicornu marinum, ‘sea unicorn’.

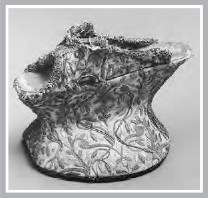

A visitor from Nuremberg, Georg Christoph Stirn, paid a visit in 1638, the year of John Tradescant the Elder’s death. Among the items described by the German traveller were:

The hand of a mermaid, the hand of a mummy, a very natural wax hand under glass … a picture wrought in feathers, a small piece of wood from the cross of Christ … pictures from the church of S. Sophia in Constantinople copied by a Jew into a book … many Turkish and foreign shoes and boots, a toad-fish, an elk’s hoof with three clawes, a human bone weighing 42 lbs, an instrument used by the Jews in circumcision, the robe of the King of Virginia … a S. Francis in wax under glass … a scourge with which Charles V is said to have scourged himself …5

The young Tradescant carried on his father’s work, both on the Lambeth estate and as Keeper of His Majesty’s Gardens. He went as far as Virginia to collect plants and rarities for the Ark. Under Cromwell’s rule he was left to his own devices, something that must have relieved a man whose family was so closely allied to court and nobility.

One man became a regular visitor to the Tradescant Ark: Elias Ashmole, a lawyer, gentleman scientist and passionate collector. He cultivated John the Younger, wining and dining him and drawing up his horoscope, inviting him to see witches tried at the Assizes, financing the publication of the Musaeum Tradescantianum, and even contributing various gifts to his new friend’s collection. Ashmole was well connected and it was easy for him to gain John’s ear. The Ark, he told the collector, should be preserved for posterity, well beyond the life of either himself or his wife, Hester. These words reverberated in John the Younger’s mind when his own son, John, heir to the family enterprise, suddenly died in 1652 and was buried next to his grandfather.

Elias Ashmole was at hand with advice and good counsel. He was concerned for John and Hester in their grief, and for the collection, for their legacy. Little by little he warmed them to the idea that only he had the means and the connections to ensure its survival. Finally, in 1659, he noted in his diary that the couple ‘at last had resolved to give it unto me’.6 He quickly moved to finalize the arrangement with a document signed in front of witnesses. Hester would later protest that there had been no time even to read what was stipulated in it, but Ashmole would pour scorn on this idea. The collection would be his, purchased for a symbolic shilling.

Once she had recovered from the shock, Hester used all her cunning to make the deed undone, to make her husband understand that he had signed over all his possessions to a false friend without knowing the consequences. The deed was in her possession (she had tricked Ashmole into giving it to her), and she cut off the seal. John resolved not to think of the matter any longer. In his will he bequeathed his rarities ‘to my dearly beloved wife Hester Tradescant during her naturall life, and after her decease I give and bequeath the same to the Universities of Oxford or Cambridge, to which of them she shall think fit’. On 22 April 1662, he followed his father to the family grave. The inscription on the tombstone in the graveyard of St Mary at Lambeth reads:

Know, stranger, ere thou pass, beneath this stone,

Lye John Tradescant, grandsire, father, son,

The last dy’d in his spring, the other two

Liv’d till they had travell’d Orb and Nature through,

As by their choice Collections may appear,

Of what is rare, in Land, in sea, in air;

Whilst they (as Homer’s Illiad in a nut)

A world of wonders in one closet shut,

These famous antiquarians that had been

Both Gardiners to the Rose and Lily Queen,

Transplanted now themselves, sleep here: and when

Angels shall with their trumpets waken men,

And fire shall purge the world, these three shall rise

And change this Garden then for Paradise.

This, of course, was not the end of it, and for Hester Tradescant paradise seemed far away. Ashmole was well aware what a prize lay in his grasp. By now a barrister, a Windsor Herald and a Fellow of the Royal Society, he also knew that there were ways of securing it for himself. He took the newly widowed Hester to court at the Chancery, where the case would be heard by the Lord Chancellor, Lord Clarendon, whom Ashmole knew from his position as Windsor Herald. The case was found in his favour and it was decided that he was ‘to have and enjoy all and singular the said books, coins, medals, stones, pictures, mechanics and antiquities’. Unwilling to let go once he had won, Ashmole continued to humiliate his friend’s widow with all means at his disposal, which included bringing a suit of libel against her, forcing her to acknowledge publicly ‘that I have very much wronged Elias Ashmole, Esquire, by several false, scandalous, and defamatory speeches, reports, and otherwise, tending to the diminuation and blemishing of his reputation and good name’. The document goes on listing in the greatest detail a number of complaints against her to which she now confessed.7 On 4 April 1678, Ashmole noted in his diary: ‘My wife told me, Mrs Tredescant was found drowned in her pond. She was drowned the day before about noon, as appeared by some circumstances.’ He had finally destroyed the woman who had almost succeeded in preventing him from securing the greatest prize of his career. As Hester was buried in the family tomb, Ashmole lost no time in removing the collection from the Tradescant house, starting with the family portraits. He later modestly resolved to give the collection to Oxford University, where parts of it can be seen still today, in the museum named after him. The Ashmolean Museum should by rights be the Tradescantian Museum. It is ironic that Hester Tradescant, too, had the intention of bequeathing the collection to Oxford.