Charles Willson Peale (1741–1827), the son of a convict shipped to Maryland by the British authorities, started out in life as an apprentice saddle-maker. A gifted draughtsman he quickly rose to become the portraitist of many of the revolutionary heroes of early American history; Lafayette, Jefferson and Washington among them. This was more than just a way of making money. Peale was a convinced Republican, a one-time soldier in the War of Independence and an active participant in the political consolidation of the nation.

Painting and politics, though, were never enough to fill Peale’s days. He patented steam baths, bridge designs and a polygraph, which allowed him to copy documents, and he proved indefatigable in tracking down objects and organizing their display, according to the ideas pioneered in Europe by Linnaeus and Buffon, in his museum, the finest such to be conceived in the eighteenth century.

The central part of Peale’s museum was a long gallery with natural light in which he displayed his own portraits of great Americans as a frieze running along the uppermost part of the room, while below it, both literally and metaphorically, were the exhibits of the lesser orders of nature: animals and birds skilfully stuffed and exhibited behind glass. Other cabinets contained insects, minerals and fossils.1 The museum held some 100,000 objects, including 269 paintings, about 1,800 birds, 1,000 shells, etc. Theoretical knowledge was less highly prized: the library numbered only 313 volumes. The exhibits were arranged according to the latest theories; Peale himself explained that every good collection should contain:

The various inhabitants of every element, not only of the animal, but also specimens of the vegetable tribe, – and all the brilliant and precious stones, down to the common grit, – all the minerals in their virgin state. Petrefactions of the human body, of which two instances are known, and through an immense veriety which should grace every well stored Museum. Here should be seen no duplicates, and only the varieties of each species, all placed in the most conspicous point of light, to be seen to advantage, without being handled!2

The evolution of the idea of what a collection should be like had progressed apace since the days of Sloane’s chaotic treasure troves, and certainly since the cabinets of rarities that had flourished only one and a half centuries earlier: Here should be seen no duplicates.

As far as possible, Peale’s arrangements adhered to simple evolutionary principles which seem to owe more to Buffon’s morphological ideas than to Linnaeus. While the Orang Utang was placed closer to monkeys than to humans, flying squirrels, ostriches and bats were considered suitable intermediaries between birds and quadrupeds. Backdrops painted with suitable landscapes augmented the display. Nature and natural representation were of supreme importance and as far as possible the museum was to be a true world in miniature. On the floor of the gallery an entire landscape took shape, complete with a thicket, turf, trees and a pond in which stuffed specimens of the appropriate elements (not filled with straw but stretched over wood to enhance their realistic appearance) were walking, creeping and swimming right in front of the astonished visitors. The large brown bear especially, raised on its hind legs in a threatening pose, must have made a great impression.

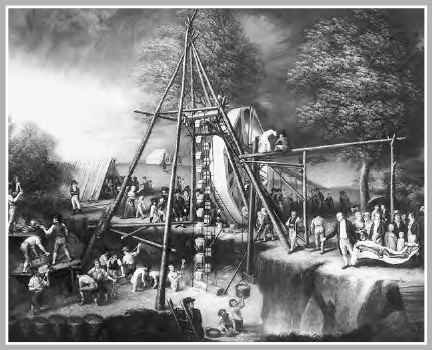

The most astonishing piece in the museum, however, came into Peale’s possession in 1801, and only after a huge undertaking, which he himself immortalized on a canvas he called The Exhumation of the Mastodon. The discovery of the mastodon, a prehistoric mammal, was a sensation in scientific circles. Even before its discovery during digging works on a farm in Newburgh, New York, scientists had written about it as evidence that species could indeed die out, a fact that further strengthened the emerging ideas of natural evolution. Peale and his son Rembrandt (all his children were named after great painters, collectors or naturalists) supervised the exhibition of the gigantic bones. In the picture, the endeavour has reached a climactic moment: a storm is threatening and the work is continued with great urgency, a large walking wheel powering a chain of buckets, which empty the ground water in the pit.

Peale himself is standing by in almost visionary pose, lit brightly in the foreground and with an anatomical plan of a mastodon leg in his hand. The people depicted around him, his family and friends, are all caught in the great anticipation of the moment, the retrieval of something believed long lost (or non-existent); and, as several people shown in the canvas were in fact already dead at the time of the exhumation, they too are thus retrieved. In this moment of private myth they were as present as they certainly were to Peale throughout his life; the painting echoes motifs of another canvas in his collection, a copy by his own hand of Catton’s Noah and his Ark. In both cases, the father is helped by his sons, rescuing the glories of creation. The parallels are obvious: death is vanquished, nature tamed and subdued by wisdom.3 The mastodon was installed in Peale’s museum and drew in great crowds wishing to see the remains of the monstrous animal. To its owner, however, it was not so much a crowdpuller as proof of everything he believed in.

One class of exhibit which Peale dearly wished to have in his museum was never realized. While he considered portraiture an adequate means of granting a form of permanence and immortality, he continued searching for a ‘powerful antisepticke’ in order to preserve actual bodies and prevent them from becoming ‘the food of worms’. Although he never did find an embalming technique that would have allowed him to put his plans into practice with human bodies, events in his private life illustrate his profound beliefs and anxieties connected to death and disintegration. When his wife, Rachel, died, probably during her eleventh pregnancy, he refused to have her buried for four days, for fear of putting her into her grave alive.

Years earlier, he had painted a portrait, Rachel Weeping, on which he worked intermittently for four years, and which shows the disconsolate mother grieving over the corpse of their fourth child, Margaret, who had died in infancy, as had the previous three.

The picture shows the mother looking heavenwards, while the child lies in its bed peacefully, dressed for burial. A medicine bottle in the background illustrates both the efforts that were made to save the infant and the powerlessness of human endeavour in the face of fate. The painting was hung behind a curtain, making every time it was revealed a renewed moment of immediacy. Peale was much concerned with arresting the present, and with the eventual but inexorable disappearance of everything he held dear: another of his paintings shows two of his sons, life-size, vanishing through a doorway and up a spiral staircase, walking out of view, a presence that contains an absence. He displayed it so as to make it seem as realistic as possible, fooling many of his visitors in the often dim light before electricity. Peale himself was also permanently there, if not in person then represented by a wax figure of himself, which he had placed in the museum in 1787. His preoccupations, most significantly the collection itself, illustrate his acute and agonizing awareness of mortality, of the inexorable passing of time and of those dear to him. Establishing permanence and thus cheating death of its triumph, through portraiture, through embalming, through scholarship and through remaining present in a museum designed to outlast him and his children, was his primary concern.

Peale’s roles as founder of America’s first museum and as painter of its greatest heroes coincide in a large self-portrait. It shows him holding up a heavy curtain separating him from the long gallery in which birds stand upright in their glass cases underneath the busts of great men while visitors take in the treasures on show. Peale did not flatter himself: he appears as an old man, slightly bent over, his head bald, one hand held out invitingly (or is it to ward off intruders?) while the other supports the velvet. At his feet is a dead turkey spread over a toolbox, America’s national animal in the process of being admitted to taxidermic eternity, while to his left is the jaw of a mastodon and two further bones leaning against a table, a full skeleton partly visible underneath the lifted curtain. Peale was thus opening his collection to the visitor, offering entrance to wisdom, order and to a life without end.