We cannot but wish these Urnes might have the effect of Theatrical vessels, and great Hippodrome Urnes in Rome; to resound the acclamations and honour due unto you. But these are sad and sepulchral Pitchers, which have no joyful voices; silently expressing old mortality, the ruines of forgotten times, and can only speak with life, how long in this corruptible frame, some parts may be uncorrupted; yet able to out-last bones long unborn, and noblest pyle among us.

Thomas Browne, Urne Buriall1

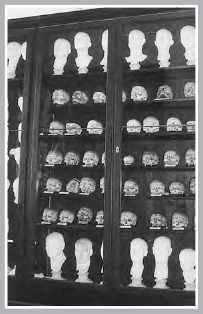

Dr Gall’s collection of human skulls and plaster casts is kept in the idyllic town of Baden, a little under an hour away from Vienna by slow train, a comfortable ride through the suburbs and the vineyards of the Josephsbahn. The Emperor Francis Joseph liked to come here in the summer and a convenient railway stood at the ready to transfer His Majesty to his place of choice. In Baden, in a rather splendid neo-Renaissance villa, the Gall Collection fills one room, just next to that of Dr Rollet, who amassed curiosities, fabrics, snail houses, cameo casts and insects. A menacing mask leers above the entrance door of the house.

Gall’s collection is a curious testament to a scientific mind. In large, old glass display cases rising up the entire height of the wall are rows and rows of labelled skulls, which he got from the local lunatic asylum and from the gallows. They are mounted on simple stands and labelled in a neat hand. ‘His folly: Believed he was an emperor’, reads one, ‘Her folly: Drinking herself to idiocy’, another. There are human lives here, slow descents into insanity, alcoholism, crime and misery, each summed up succinctly in a single sentence: She killed all her children; He could not stop singing and laughing; He believed himself inestimably rich, etc.

Apart from the skulls, there are full plaster casts of heads taken from people alive and dead. While the skulls mainly belong to ‘deviants’, the criminal and the insane, some of the casts depict the great and the good: Napoleon is here twice (once from life, once in Antommarchi’s death mask), Goethe and Schiller, and also assorted noblemen, mathematicians and administrators: calm, august and usually bearded incarnations of distinction. Many of the subjects of the casts are long forgotten, some no longer have any names attached to them at all – but here they stand, looking surprised or dignified, pained or impatient (the taking of the cast was laborious and claustrophobic), or, in some cases, obviously already dead.

The lasting contribution to science and to the study of the human brain of Dr Franz Joseph Gall (1758–1830) was the discovery that different kinds of brain activity are located in different parts of the brain. This led him to believe that parts of the brain that were especially well developed must be larger than others and must therefore imprint the signature of a person’s character and ability on the formation of the skull. It was in an attempt to prove this thesis that Gall chased every head that he considered interesting, from those who had died insane to those who were considered great. His findings were rooted in the Enlightenment. In line with the allegorical thinking of the time, Gall had localized the baser impulses at the base of the skull (the lust for murder, thievery and violence behind the ears), while the highest leanings, faith and theosophy, inhabited the very apex of the cranium.

This science, phrenology, became so controversial and so popular that the Catholic Emperor Franz II forbade Gall to disseminate and teach his materialistic theories in Vienna. With only a few skulls to illustrate his ideas in his luggage Gall left for Germany and finally settled in Paris, where, having been forced to leave behind his collection, he accumulated a second, larger, one, which is now kept in the Musée de l’Homme in Paris. His theories were later taken up by eugenicists and given even greater prominence by the Nazis in their illusion of being able to measure their way to a pure and glorious master race.

I had come to Gall’s collection to visit an old acquaintance, Angelo Soliman, who had died in 1796 and whose plaster cast had only recently been identified among the heads. The curator and city archivist showed me to the case, though I had recognized Soliman the moment I entered the room. It is the full-head cast of an old man. The left shoulder is missing, broken off some time during the last 200 years.

Soliman does not look at me; his eyes are half closed. He has a handsome, African face, with a well-formed, slightly flat nose, broad cheekbones (the weight of the wet plaster flattened the face), large, almond-shaped eyes and firm, regular lips. He was famous for his appearance, and it is easy to see why. He must have been a sight both dignified and powerful in his lifetime. His hair is short and frizzy and he is bold, an old man. The mouth is slightly opened and the pupil of his right eye protrudes from underneath the lid. He suffered from cataracts in his old age. The mask was clearly made after his death. Gravity was at work on this face, and the corpse was lying on its back when the mask was taken. The skin covering the cheeks has sagged towards his ears, opening and broadening his mouth. There is a skin fold under the left ear and the cheeks are hollowed. The whole face has the emaciated look of a body suddenly without life. When the bust is tipped backwards Soliman’s eyes look back at me from underneath their heavy lids and the open mouth makes him look surprised. His death came as a surprise; he died in Vienna, the city that had been his home for most of his life, on the open street, of a stroke.

Angelo Soliman had arrived in Vienna after a long and curious journey. He was born, most likely, in what is today northern Nigeria, at around 1721, and was then enslaved and sold to north Africa and from there to Messina in about 1730. Here Prince Johann Georg Christian Lobkowitz, the Austrian Governor of Sicily, saw the pageboy and requested him as a present when he left to take up his next post as Governor of Lombardy. His wish was duly granted, and the thirteen-year-old Angelo had a new master.

Lobkowitz was a soldier, and his young page became his companion in battle, widely admired for his courage and daring. The years of military campaigns saw the growing boy turn into a young man and took him throughout the Habsburg Empire together with his master’s armies: from Italy to Transylvania, to the Czech lands, back to Italy, and then to Hungary. On Lobkowitz’s death, he entered the household of Prince Wenzel von Liechtenstein. Now a man of thirty-four, Angelo settled in Vienna for good.

A portrait shows him as a very striking young man in his finest court uniform: a light, fur-trimmed overcoat with a buttoned coat underneath, and a neck scarf.

His regular features are set off by the white turban that he seems to have worn constantly, and in his right hand he holds an ornamental staff in the manner of officers and gentlemen. The handle of the staff is decorated with a lion attacking an antelope, and in the background the oriental theme is reinforced by a palm tree on a hill, as well as two pyramids. Despite this incongruous scenery the figure in the front loses nothing of his dignity. The legend of the image reads with all rococo ceremoniousness: Angelus Solimanus, Regiae Numidarum gentis Nepos, decora facie, ingenio validus, os humerosque Jugurthae similis. in Afr. in Sicil. Gall. Angl. Francon. Austria Omnibus Carus, fidelis Principium familiaris. (‘Angelo Soliman, from the royal family of the Numidians, a man of beautiful features, great wit, similar to Jugurtha in face and build, dear to all in Africa, Sicily, France, England, Franconia and Austria, and a faithful companion of the prince.’)

Angelo was saved from ornamental obscurity by his accomplishments and by the ‘great wit’ attested to him in the inscription. He may have cut a dash in his silver-trimmed court dress but he was also a soldier of some repute in his own right and had acquired a considerable education. He was fluent in German, French and Italian, and spoke some Czech, English and Latin. Having risen to a position of great respect at court he was accepted into the Masonic lodge Zur Wahren Eintracht (‘True Unity’), where he became the brother of, among others, Mozart and Haydn. As a Mason, Soliman dealt as equal with the very cream of society, with the same people Mozart himself knew.

Soliman died on 21 November 1796, at the ripe old age of seventy-five. This, however, is not the end of his story. What happened next is related by one of his Masonic brothers, a certain G. Babbée, who writes about Soliman’s posthumous fate:

Further it has to be recorded

1. that, on order of the Emperor Franz II, he was skinned,

2. that this skin was fitted on a wooden frame and so resumed Angelo Soliman’s former features with great exactitude and was exhibited publicly for ten years,

3. that this skin on its wooden frame or the sculpted shape of our brother Angelo Soliman was consumed by fire and flames 52 years later under great noise, and that at this occasion also his former master of the chair, the cursed arch heretic, atheist, monk hater and freemason, the imperial and royal counsellor J. von Born was burned in effigie.

All this sounds, I must admit, damnably paradoxical, but it will be shown to be entirely true and correct, once I am allowed to explain my words properly2

This explanation is relatively simple: Angelo Soliman, page-boy, soldier, companion, courtier and tutor to a succession of princes, had become a star exhibit in the cabinet of natural curiosities of Franz II, a man who had inherited his family’s genius for collecting, and few of their other qualities.

A history of the collection describes the former Soliman’s new abode as follows:

Angelo Soliman was depicted standing up, his right foot put backwards and his left hand reaching out, dressed with a feather belt around his loins and a feather crown on his head, both made from red, blue and white ostrich feathers in changing sequence. Arms and legs were decorated with a bead of white glass pearls, and a broad necklace braided delicately out of yellow-white porcelain snails (Cyprinid Monet) hung low down on to his chest.3

Soliman’s temporary resting place, which went by the somewhat cumbersome appellation K. K. Physikalisch-astronomisches Kunstund Natur- Thierkabinet (‘Imperial and Royal Physical Astronomical Art and Nature and Animal Cabinet’). The director, Abbé Eberle, had grand plans for the new quarters of the collection in the Josephsplatz near the imperial library. It was to be nothing less than spectacular. When it opened its doors to the citizens of Vienna in 1797 it was part fantasy and part cabinet of curiosities.

The walls of the exhibition rooms were decorated with landscapes commensurate with the habitat of the animals displayed in them. In addition to these grand panoramas, the rooms contained artificial grass and trees, rocks and ponds, glass waterfalls and model oceans with undulating waves. There were fields of grain and whole landscapes dotted with picturesque ruins and a farm with chicken coop. Strong as this arrangement was in effect, its scientific merit was not quite of the same order. The Asian room, a landscape suggesting endless, Siberian forests, displayed a musk-ox and a deer surrounded by singing birds and parrots. The rooms were crammed full with specimens, none of them labelled, but mounted in their artificial surroundings to the greatest possible effect. In one of the European rooms, visitors could admire a hunting scene with a fox fleeing a pack of dogs and a rural idyll with farming implements strewn around as if the labourers had just walked off to have lunch under a nearby tree.

Amid this rococo view of life the ‘noble savage’ Soliman, for that is what he had become, had a cabinet all to himself, and among the themed splendours of the naturalia on display an entire room was dedicated to the effect he created. ‘The fourth room in the left wing,’ the historian L. J. Fitzinger relates,

… contains a single landscape, a tropical wood with shrubs, watery parts, and canes. Here one could see a water pig, a tapir, some bisam pigs and many American swamp and song birds in different groupings. In the same room, to the left of the exit, from which one can reach the main staircase through a long corridor and through the library, there was a glass case in the corner, painted green. The door, which forms the front wall of the cabinet, was masked with a drape of green cloth and the interior of the case was painted in brilliant red. In this case Angelo Soliman was kept and was shown to the public especially by a servant before they left the department.4

The emperor seems to have been well pleased with this artistic new addition and with the advantageous effect of contrasting the handsome figure with the grotesque features of the tapir and the various pigs. The case became an attraction in itself, a fitting grand finale to the tour of the imperial collections.

Abbé Eberle’s morbid extravaganza was on display until 1802 when Franz II, tired of his director, appointed a new man charged with the unravelling and proper cataloguing of the collection. The result was a scholarly dampening of Eberle’s grandiloquence; the landscapes were not dismantled, but the exhibits themselves were rearranged and labelled in German and Latin. Some scientific displays, such as a series of preparations in twenty-four glass jars illustrating the embryonic development of the chicken, were also added to the collection. A second overhaul finally got rid of the theatrical backdrops.

Angelo Soliman’s daughter, Josephine, meanwhile, had carried on a long and desperate battle to have her father’s skin returned to her so she could bury it with the rest of his body. Her request remained, needless to say, unheeded, despite an intervention by the Prince Archbishop of Vienna.

Angelo was not to remain alone; in 1802, a black girl, also stuffed, a present from the King of Naples, was fitted into the same cabinet, together with an African male nurse from the hospital of the Merciful Brothers, and an animal warden from the Schönbrunn Zoo. In 1806, the new director of the collection, Karl Schreiber, finally found that exhibiting four stuffed black ‘representatives of mankind’, as they were referred to officially, might be unseemly, and they were eventually moved into the attic. On receipt of an adequate sum servants could still remember the way and would show visitors to this sad and silent group of exiles.

The end of Angelo Soliman’s second incarnation as wild man, exotic fiction, scarecrow for small children, money-spinner for servants who would draw the curtain on receipt of a special gratuity, and as an object of a collector’s unlimited greed, was as dramatic as it was historically apposite. In the famous year 1848, when democratic riots shook the German-speaking countries, he was indeed to be ‘consumed by fire and flames … under great noise’, as the Freemason Babbée had written, and it was another prince of the Habsburg Empire who brought about this infernal conclusion.

On 31 October, the troops of Prince Alfred Windischgrätz bombarded the inner city of Vienna in order to subdue the revolutionaries. A single, wayward cannonball hit the part of the roof of the imperial palace that housed the zoological collection. The entire scientific work that the eminent Karl Freiherr von Hügl und Agnelli had brought back from his expeditions was burned, together with other specimens. The inventory of the catastrophe lists, towards the end, after detailing damage to cases, butterfly collections and ‘other beasts’:

[A]lso among humans the negro Salomon Angelo over wood artfully preserved by the sculptor Thaller, a second negro of chief nurse Narciss, a gift from the Merciful Brothers, fitted on wood by the sculptor Schrott including their case, a third, who had been employed by the k.k. Menagerie in Schönbrunn … and a stuffed negro girl, who had come as a present from the King of Naples.5

The exhibits were obviously not important enough to have been entered into the inventory with individual numbers.

There are many monuments to our mortality, all preserving death at its most lifelike, in the anatomical collections of hospitals and universities. One such collection is housed in the Narrenturm, or Tower of Fools, in Vienna, which used to be a lunatic asylum before being turned into a museum, a curiously forbidding building in the grounds of Vienna’s eighteenth-century general hospital, today the university campus. Half hidden by trees the Narrenturm looms in the furthest corner of the grounds. The plaster is falling off in large lumps from its rusticated façade, especially around the window frames, where the brick is revealed, making it look as though the building is suffering from some terrible skin condition. It has something of a fairy-tale tower or castle air about it, hermetically sealed against the outside world – cruelly appropriate for those of its former inhabitants who, as Dr Gall’s collection shows, believed themselves princes and emperors. Its unfortunate inmates have made place for another panopticum of wretchedness: the Federal Museum of Pathology.

This collection, the largest of its kind, was begun in 1796 as a teaching aid for the new hospital. Like the building in which it was to be housed later, it was an expression of a new way of seeing humanity and human illness. Medicine was freeing itself from doctrines laid down by Galen 1,500 years earlier. Surgery was slowly being recognized as a discipline that should not be left to quacks, barbers, horse castrators, butchers and hangmen. The modern hospital embraced these ideas, and work in the mortuary was accepted as an important part of medical science. Johann Peter Frank, who became director of the hospital in 1795, was determined to give a systematic foundation to this new science and to create a repository of specimens that could be used to compare and to instruct. Thirty years later, the collection already encompassed more than 4,000 specimens, either in spiritus or as skeletons separated from the flesh with acid. In 1971 it was transferred to the Narrenturm.

Today the tower is part museum part anatomical collection, and visitors enter the building through incongruously modern wrought-iron doors – the tower served as a home for nurses for a while. It is impossible to escape the claustrophobic feeling of the curving corridors and cells and the concentrated misery of the ‘preparations’, among them Vienna’s last remaining stuffed human being: the body of a little girl, standing up, one foot set in front of the other, supported by a staff running through her body, and put unceremoniously among jars of deformities. At the time of her death she had been between four and five, and her entire body is covered by black, fishlike scales. Her face looks like that of a life-sized doll. She is bald and her hands and feet are mummified on their original bones, as the guides relate with solicitous informativeness. She was prepared in 1780 and was later exhibited in the same collection as Angelo Soliman. Nothing is known about her cause of death, or about her identity. The body underneath her skin is cast in wax.

The golden time of the collection, the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, provided fertile ground for such displays, when there were as yet few effective treatments for many terrifying illnesses. The devastations of syphilis and leprosy, grotesque tumours and skin conditions are all here, re-created painstakingly in wax and painted after the original. They still look absolutely lifelike. The preparer’s skills are also evident from objects such as the head of Georg Prohaska, a groom who survived for a full ten years without a lower jaw after it had been shattered by the kick of a horse. A wax replica of his head, complete with neckerchief, long hair and aimlessly lolling tongue dribbling saliva on to a decorous pedestal, can be compared to the head itself, colourless and suspended in a jar of spiritus with a fine glass lid. There are about 50,000 objects, most of them in glass jars or, after the recent acquisition of some smaller collections, in large white plastic buckets.

This museum is no place for women expecting children. Much of the collection consists of deformed newborns who were born dead or died soon after birth. In the crammed former cells and corridors of the asylum, assembled in the form of tiny, floating bodies, is the entire demon world of Greek mythology: cyclops, creatures with bulging eyes and no brains, Siamese twins joined in every conceivable place, bodies with too many extremities, hands with too many fingers, feet with too many toes, claws instead of hands, and the swollen brains of hydrocephali. A special section is occupied by the collection of ‘dry preparations’: skeletons, largely of people who lived into adulthood. The English Sickness, rickets, has wrought most havoc here, with arms and legs transformed into spiralling growths, powerless appendages to useless bodies. Other specimens illustrate the effects of tuberculosis, tumours, syphilis and spina bifida. A silent assembly of skeletonized Siamese twins seems to be engaged in a grotesquely intimate waltz.

In contrast to the work of Frederik Ruysch and to the graceful anatomical wax models produced in the eighteenth century (some of which are kept a stone’s throw from the Narrenturm), this collection speaks of a different attitude to human life, to mortality and to dignity. Human bodies had been deserted by the divine spark and the ideal of beauty once thought inherent in them and in every representation of anatomy. Ruysch’s conflation of beauty and mortality and the gracefully instructional vanitas tableaux of the eighteenth century had no space here. They had been replaced by a mode of research and teaching that treated bodies quite dispassionately as objects, much like rock samples or beetles. This ideological gap was to widen during the twentieth century and was to reach its nadir in the anatomical collections of Nazi Germany, which would routinely use concentration camp inmates to widen the scope of the specimens. Rumour has it that some of the heads collected by the pathologists of the Third Reich are still held in deep cellars while an embarrassed administration is unsure what to do with them.

Whatever collections try to master it cannot be closer to the bone than collecting the bones themselves. Nature and culture, the past and the present can all be the subjects of collections, of building small ordered worlds amid the chaos all around. If a collection really can promise eternal life then these assemblies of the dead carry this promise by daring us to face them down and learn from the deaths already passed. As graveyards traditionally combine the reality of death with the promise of transcendence and of an afterlife, those collections that had the human body as their object throw down the challenge of the Delphic Oracle: Know Thyself.