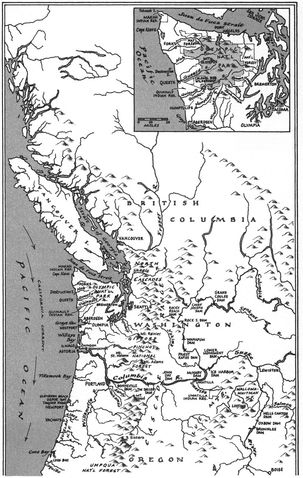

Northwest

OLYMPIC PENINSULA

Pacific Northwest

In a quiet stream high in the mountains’ dark forest, a single salmon, scratched and dazed and already spotted with a rotting white fungus, is finning weakly in the slow current. Hers has been a life of almost magic and miraculous luck. She has done all a salmon can do. And here, spawned out, spent, fulfilled, that life will end. A time to die. She drifts slowly downstream until she hits a gravel bar. And for the first time since she hatched and wriggled from the gravel of this very stream, she stops swimming, forever.

From the ocean—from a fish’s-eye view—the place of spawning must seem like the gates of heaven itself, since the prospect of getting there entails a pilgrimage up toward the mountaintops and into the enshrouding clouds. And if the holy among humans are inspired to ascend similar high places to come closer to God and receive visions or commandments for the ages, it is perhaps as remarkable and holy that the salmon commit so fully and so fatally to their hegira of sex and sublimation, death and rebirth, unwitting though they probably are.

I wonder if a vision of her life is passing before her as she lies here with that one unblinking eye staring up at the enormous trees overhead and the sunlit sky beyond them. I suppose not. I can only suppose that she has no recollection of the urges that have driven her, no recall that as a youngster she left this stream to travel under the ocean’s broad roof to the deep heart of the sea and back. And I suppose she cannot now remember fighting her way against the river’s torrent and leaping up sunlit falls and choosing a strong mate. Does she even know that she has laid her eggs, fulfilled her part in shaping the future? Can she remotely realize that each day she lived, comrades fell to natural catastrophes and cunning predators and diseases and accidents and nets and hooks and the structured works of humanity? As she lies dying here, can she possibly understand that she has survived?

Everything that could ever go right for a salmon has gone right for her. But for most salmon here along this coast, the reverse applies.

Once, salmon were merely the world’s most complicated fishes, spending part of their life as freshwater fish, part as saltwater fish, and yet another part again as freshwater animals bent single-mindedly upon self-destruction through reproduction—immortality through suicide. These different stages demand extreme physical changes and navigational abilities as advanced as any living being’s and more advanced, by far, than most. Ranging as they could from the Continental Divide to the center of the ocean and back within one relatively short, humble, heroic life, the salmon’s story was exceptional by any measure.

That life and story has become increasingly complex. Nowadays, one cannot see the salmon’s world without adding to the tale the plot complications of logging, agriculture, hydropower, dams, politics, pesticides, foreign markets, private property rights, public property fights, recreational, commercial, and subsistence fishing, and artificial reproduction. And one cannot see those subplots without confronting the heights and depths of the human spirit, no less than a salmon can confront life without ranging between the purest of springwaters and the bottomless depths of the deepest sea.

Shuttling as they do like silver threads between upland and ocean, abyss and summit, salmon tightly stitch the interlock between continent, torrent, and tide, binding together everything humans do to land or water. And we do much.

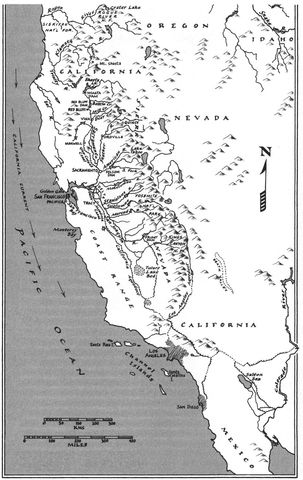

The Great Northwest of the United States and Pacific Canada have become the world’s extinction epicenter for ocean fishes. Nowhere else in the world are ancient lines of marine fishes vanishing with such haste. Pacific salmon have disappeared from about 40 percent of their breeding range in Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and California. In this region, salmon are either extinct, endangered, or threatened in two-thirds of the area they occupied ten decades ago. Extinction is an unusual form of death, because while most death adds a spoke to the wheel of life, extinction carries a peculiar finality—an end of lineages, a preclusion of futures. As the poet Gary Snyder put it, “Death is one thing, an end to birth is something else.”

Hope paces impatiently. Salmon are still abundant in Alaska, and lessons learned in the Northwest—if we learn them—could be applied there; there is still time. The Pacific Northwest, then, offers much we could study. The Northwest is perhaps the best place in the world, for example, to study finger-pointing elevated to art. So rarefied and pervasive is this trait that even the best and the brightest seem to do it unconsciously, by subtle alterations of emphasis, the way you shift unthinkingly in your chair if you need to displace pressure. It is also a place to study an extreme range of views and policies, from people who tried to exterminate salmon with poison to people who worship the fish.

Either way, whether salmon represent your demons or salvation, they loom large here. Think of the Northwest, and salmon soon come to mind. Only a few wild animals symbolize the heart and soul of a region. Tigers in India, lions and

elephants in Africa, kangaroos in Australia. In North America, the buffalo of the Great Plains and the salmon of the Pacific Northwest supported economies, cultures and human self-identities. And though white settlers destroyed the buffalo in greed and in genocide against the natives, they embraced the salmon. The immigrants, like the native peoples, saw in salmon something deep, powerful, moving, and valuable—even if they approached the fish with less awe, less reverence, and, consequently, less success than the natives had for millennia. Certain other animals still symbolize their regions. But salmon are unique because their symbolic power and their economic value have survived together to the threshold of the twenty-first century. And this holds the best hope for salmon and the people who need them.