CHAPTER 1

Sensory Modulation Basics

_______________________________________

Every second the brain processes an enormous amount of data that have been gathered by the skin, eyes, nose, tongue and ears and sent to the brain along nerve pathways. We also process a wide variety of internal body states that include muscle movement, balance, temperature, pain, gut sensations, and breath. Inside the brain, each sense organ’s input is organized and encoded. Higher level circuitry identifies the sensation and decides whether to attend to it, store it, and share it with other senses and cognitive processes. This is “sensory processing,” and when it is dysfunctional, we say that the person has a Sensory Processing Disorder (SPD).

Poor sensory processing is at the heart of many different functional problems that affect our ability to sense, identify and make use of external and internal sensations. It also affects our ability to coordinate our body movement (praxis). Attention and memory circuitry within each sense’s cortical region can also fail, causing problems such as poor attention to visual tasks and poor auditory memory.

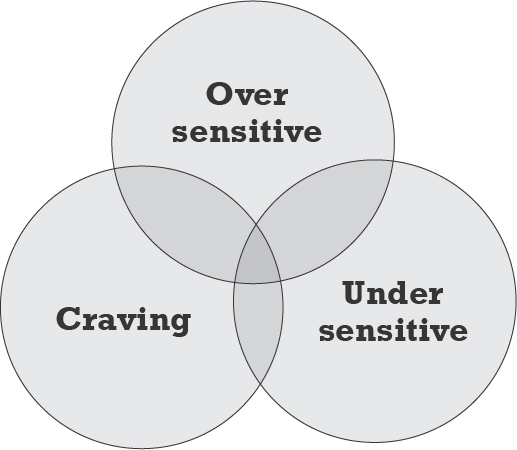

Sensory modulation, a subset of sensory processing, is concerned with each sense’s degree of sensitivity (e.g., sensitivity to light touch) and with the brain’s ability to regulate physical, mental and emotional reactions to sensory input. When a person is unable to regulate normal environmental sounds, light, smells and so on, we refer to the problem as poor sensory modulation. When people are highly dysfunctional in this regard, we say they have a Sensory Modulation Disorder (SMD). SMD includes three types of symptoms: over-responsivity, under-responsivity, and craving of sensory input. (I use the simpler terms, oversensitive, and undersensitive, to stand in place of over-responsive and under-responsive.) These symptoms can affect one or more of a person’s senses. The three types of symptoms are independent problems, and so they can simultaneously occur in a single sense.

We are still in the early stages of understanding SMD’s causes and how to assess and treat it. Let’s take a brief look at what we know.

Oversensitivity comes from having a low threshold for sensation such as light, soft touch, noises, pain, aromas. Children with this problem become easily overwhelmed with sensation. Think of it as the “volume knob” on sensory input that is turned up too high, or as a lack of habituation to sensation. Acute oversensitivity can make social situations difficult to endure, as the examples below illustrate.

A child who is undersensitive doesn’t register what others do. Although the problem is not generally emotionally disturbing, it can be dangerous. The child might have difficulty registering sensation such as smells, pain, temperature or balance, leading the child to be at risk for burns, injuries and falls. Without normal stimulation, the child can easily become bored, resulting in low alertness, inattention and sometimes sedentary behaviors. We can think of this problem as the “volume knob” turned too low or as signals in the brain not “gating” properly (that is, the signals are slow or poorly synched).

The craving of sensation typically occurs as a side-effect of oversensitivity or undersensitivity. Such craving is the incessant seeking of certain types of calming input that feel good (due to oversensitivity) or the constant attempt to experience sensation (due to undersensitivity). Commonly, we see children touching people or things, seeking out music or visual input, or sniffing things. Some children crave movement and their hyperactive behavior can be mistaken for ADHD.

Children with Autism and SMD

Children with ASD appear to have additional underlying causes of sensory sensitivity. Current research is focusing on “noisy” brain waves, lack of dendritic pruning, the connectivity between brain areas and the thickness of those connections. Some researchers note a general problem of signal bleed-over between sensory regions in the brain—both sub-cortical to cortical—and between individual sensory cortexes (such as visual and auditory).

Common problems for children with ASD include oversensitivity to smell, taste, sound and touch. Activities such as combing hair or clipping nails can register on the child’s pain scale.

To get a sense of the problems children face, as well as the degree to which the problems linger through the years, let’s look at some symptoms of poor sensory modulation. The example below describes the experiences of seven adults who have just arrived for a community meeting at city hall. Each person has a small or large modulation problem. Although each is now able to stay regulated in a social environment, they all had more serious issues as children.

• Marcus enters the room first and turns on all the lights: the fluorescents, the chandeliers and the spots. He then takes a seat and checks his email. He doesn’t hear his friend, Ali, say hello to him from the doorway. Marcus is undersensitive to both sound and light. He is also a very picky eater and has symptoms of autism disorder spectrum, but not severe enough to have been diagnosed.

• Esther walks into the brightly lit room, shields her eyes and thinks, “Whew! This room’s bright enough to do brain surgery in.” She is sensitive to light. As a child, she used to scream when her sister turned on lights. Now she notices it, but doesn’t complain.

• Erica walks in talking loudly to her friend, Miguel. Erica has a loud voice that often irritates her coworkers, and she is undersensitive to its volume. Erica chatters constantly and, in fact, she does so compulsively; she craves talking.

• Jon sits off to the far side. He is wearing a new silk shirt that feels luxurious to him. But the tags in the shirt are another matter. He had to cut them out prior to putting on the shirt. He is carrying a loosely woven, thick cotton sweater, and he plays with it nonchalantly, wrapping it around his hands to feel the texture with his fingers as he settles into his seat. As a child, he cringed when others touched him. As an adult, he is still sensitive to being touched, but doesn’t react overtly to it. Although he is sensitive to touch and loves to touch soft textures, he is not overly sensitive to sound and doesn’t even notice how loudly Erica is talking.

• Jon’s wife, Tania, fidgets as she sits next to him. She has high energy and is constantly in motion. As a small child, her parents wondered if she had ADHD. She does, but she also has SMD, and she craves the sensation of movement.

• Andrew, wearing dark glasses, takes a seat in the back away from everyone else. He appears nervous. He had SMD as a child and continues to experience its symptoms as an adult. He doesn’t like to be touched, and he doesn’t tolerate light, loud noises (especially Erica’s high-pitched voice) or smells. He noticed the scent of perfume as he entered and he is now obsessing on it. His thoughts tend to be disjointed and in a loop: “I asked the principal to send out a reminder telling people not to wear scent tonight. It’s not right. They asked me to come. They should be considerate. I should leave.”

• Miguel, a big easy-going man, slouches in his chair, crossing his arms and legs so they don’t sprawl. He observes Andrew’s dark glasses and nervous behavior and wonders about it. As a child, Miguel was undersensitive to sound and to sensations from his body. As a result, he had poor attention skills at school, and he was sedentary and somewhat overweight. He continues to have those issues, although coffee helps him to attend. He was diagnosed with the inattentive form of ADHD, but medication didn’t change his symptoms. He doesn’t have ADHD. He has SMD.

Through the years everyone in this group has learned strategies to compensate for their poor sensory modulation. As children mature into adulthood, most learn to tune out irritants and to tone down reactivity. However, some continue to struggle with unobtrusive symptoms that compromise their ability to function in normal environments and social settings.

The ‘Upside’ of SMD

There is an “upside” to having SMD symptoms. The child with oversensitivity might find nature, art, music, and touch to be exquisitely delightful as long as he is able to regulate the input. Alternatively, the person who craves sensory input has built-in motivation for learning a craft, art or skill that can provide that input. Craving might give the child the discipline to become a good musician, cook or runner. The child with undersensitivity is less disturbed by environmental factors than others, which sometimes produces an easy-going, laid-back personality.

Interoception

A common oversight is to restrict the conversation about sensory modulation to the five external senses, or to those five plus body movement and balance. There are additional internal senses (pain and temperature, for example) where modulation can be problematic for children with autism and other special needs. See the table for the traditional list of internal senses.

External senses |

Internal senses |

• Vision |

• Temperature, pain, itch |

• Hearing |

• Vestibular (balance) |

• Taste |

• Proprioception (sense of body) |

• Smell |

• Hunger, thirst |

• Touch |

• Voiding |

Another Look at Processing and Modulation

Let’s revisit the process of registering, processing and acting upon sensory input. This time we will go further into the sensory-modulation circuitry.

Processing sensory data starts with the actual sensor (the eye, for example), which gathers light and color. That data is sent via nerves to the brain stem, up through the midbrain via thalamic tracts and into specialized cortical regions of the brain which attend to the raw input, identify it, and eventually store it in the sense’s memory. As a part of that process, input from left and right sensors (for example, sound from both ears) cross to opposite sides of the brain via special tracts and the corpus callosum and then are integrated. Each sensory cortex performs initial identification of what it has received and then shares its findings with other relevant senses (e.g., vision shares with auditory) in the association cortex regions (the regions that integrate different types of input). If the sensory input was unusual or noteworthy, it is routed, along with cognitive and emotional data, to the cause-and-effect region of the brain: the right anterior insula (rAI) and the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC). The rAI decides what the brain should attend to, while the ACC triggers actions to take. Internal states such as hunger and body temperature are also monitored and acted on. Strong sensory input causes actions to be taken:

• It’s too bright → put sunglasses on.

• I feel hunger → go find food and eat.

Not all strong input is attended to. The sun may be hurting my eyes, but other senses, cognitive states, or emotional states may contend for and win attention from the rAI. Resultant actions are typically motor or inhibitions of motor. Even sensation of felt emotions might cause motor changes to the face and gut. Actions might alter cognitive states, as well.

Here is an example of the decision-making process:

Jon is sensitive to sound, and his little sister likes to provoke him. She opens his bedroom door and blasts loud music to get a reaction. The loud volume is reported to Jon’s rAI and selected for importance. A moment later, his rAI also notes strong feelings of irritation, as well as cognitive information informing him that he’s seen this pattern of behavior from his sister many times before. The rAI attends to all of this and sends a decision to act to the ACC. Possible actions include:

• Jon could scream and slam the door

• He could inhibit those actions and quietly close the door

• He could glare at his sister with no reaction at all

• He could make a plan for revenge

In previous months, the noise would have triggered his scream. But he has been working on staying calm. As the sensory input arrives in the rAI, it is tempered by cognitive input reminding him not to react. He makes a decision to inhibit reacting. His ACC delivers motor commands to leave face muscles unchanged. He is proud of himself for not reacting, and now his emotional state adds weight to the decision. He decides to ignore her. His ACC delivers motor commands to quietly close the door.

The combined rAI and ACC are the final component in sensory modulation for all three types of symptoms (oversensitivity, undersensitivity and craving). They give us the opportunity to modify our behavior rather than to react to noxious sensory input, cave in to cravings or zone out due to low sensory registration. The combined rAI and ACC allow us to learn habits that will inspire a better response to the environment.

As with understanding the causes of SMD, we are still in the early stages of finding which strategies and interventions are effective. Many strategies and interventions have been found to be helpful to the child with sensory modulation disorder, and they are included in my book, Self-Regulation Interventions and Strategies. Here is a fairly exhaustive list of approaches you could take when working with a child. We’ll look next at intervention effectiveness.

1. Try to eliminate the noxious input in the environment.

2. Give her greater control over her environment so that she can independently reduce the “volume” of the sensory input.

3. Try to block the input from her sensors (ears, eyes, mouth, nose, skin).

4. Try enriching the environment so that she is exposed to new, but pleasant sensation.

5. Mask unpleasant sensation with pleasant sensation.

6. Gradually expose her to a variety of input so that fewer sensations are “noteworthy” and cause a reaction.

7. Use desensitization techniques to help with acceptance of unpleasant input.

8. Train her in stress reduction so that her response to unpleasant input is moderated.

9. Train her to focus her attention on something else when there is unpleasant input, hoping that with time she will learn to ignore unpleasant sensation.

10. Train her in cognitive strategies and self-talk she can use within the rAI to help temper the response.

11. Educate her on the upsides of having SMD, and help her find ways to use her special set of sensitivity skills.

12. Immerse her in pleasant sensory input so she can relax and find joy.

The list is a mixture of approaches, strategies and interventions. Many approaches have been tried, but not many have been validated with rigorous study. The general approach that appears to work is exposure to sensory input. There are several classes of interventions within the exposure approach. Two types in this class are gradual exposure and desensitization, and both appear to work well. The evidence comes primarily from single case studies and small studies and shows good effect. For example, Koegel, et al (2012) demonstrated a therapeutic effect using exposure techniques in the area of feeding to overcome smell and taste sensitivities.

Another approach with good evidence is the sensory treatment developed by Jean Ayers, now known as Ayres Sensory Integration®. A review by Watling (2015) showed it is an effective treatment for sensory processing issues including some forms of sensory modulation. The Ayers technique primarily covers movement as well as visual and touch processing. Therapists trained in the method also learn to extrapolate the technique to functional areas such as feeding and toilet training when the underlying issues are sensory related. For example, Bellefeuille (2013) describes therapy using touch desensitization to enable successful toilet training.

A protocol-based exposure technique called Environmental Enrichment (described in chapters 3-5) has been shown to be effective in two studies. In this method, the child with autism is gradually alerted to simultaneous sensory input to two or more senses. The child’s brain eventually learns to identify multiple streams of input, as well as to integrate data from multiple senses.

Sensory immersion, another exposure technique described in this book, promotes leisure skill development that can provide calming, pleasure and well-being. In this method, therapists and teachers use their knowledge of a child’s sensory makeup to develop new sensory-based leisure skills in the child. The technique brings to life the adage “when life gives you lemons, make lemonade.” The child learns to develop the gifts of her sensory differences and uses newly developed skills to help cope with sensory difficulties. Sensory immersion has not been studied as an independent intervention for sensory modulation. However, new research could be designed using methods and procedures, along with the detailed results of a study by Ismael (2015) who found correlations between children’s sensory makeup and their leisure preferences and participation patterns.

Other popular exposure techniques such as listening therapy and the sensory diet have been written up in informal case studies, though they have not been formally studied for effectiveness.

A Continuum of Sensory Activities

This book uses exposure to sensory input as the primary intervention and presents a continuum of activities starting from the Environmental Enrichment protocol (chapters 3-5) to desensitization techniques (chapters 6, 7 and 8) to immersion activities that increase quality of life, quell cravings, and provide practice to undersensitive circuits (chapters 6-11).

Comparing Approaches that Can be Done without Special Equipment

As described above, there are many ways to provide sensory interventions. In this next section, we compare three exposure methods: sensory diets, sensory enrichment and the Environmental Enrichment protocol. Each of these can be done outside of the sensory clinic (that is, in a setting that does not have the special equipment found in a sensory gym). Following a brief description of each, we look at factors such as focus of the intervention and ease of implementation.

The Environmental Enrichment program is a formal protocol developed to provide a wide variety of sensory input twice daily to children with autism. The program increases awareness and tolerance of sensory input and helps the senses to integrate and work together. The program can be implemented at home, at school or within the context of an early intervention program.

Sensory enrichment interventions are put together as informal programs of graded sensory input as a way of helping the child to register certain types of input such as sound or touch to increase tolerance of them. The interventions are part of the standard practice of a school-based or clinic-based occupational therapist whose typical goal is to increase sensory awareness for the purpose of improved attention and behavior in the classroom.

Additionally, sensory immersion activities are provided to stimulate pleasurable sensory experiences, helping the child to relax and gain a sense of well-being.

Sensory diets are short motor-and-sensory exercise regimes that children perform throughout the day. The exercises are chosen based on the child’s needs. The goal is increased regulation.

Comparing the Three Approaches

In general, all three of these approaches work to decrease symptoms of sensory modulation which will, in turn, increase attention skills and reduce undesirable behaviors such as meltdowns. However, the methods are quite different: they focus on different problems, and they challenge children in different ways. More important, some of them place difficult demands on the caregiver or teacher.

Environmental Enrichment (EE) exercises focus on ever-present sensory input like smells, sound and touch. Their goal is to bring the child’s attention to the environment and register input. The exercises are sometimes passive and, as a group, are less challenging than sensory enrichment exercises. The protocol stipulates two 20-30 minute periods for enrichment activities, plus optional scent and sound immersion activities.

At the other end of the exercise spectrum, the sensory diet (SD) focuses on self-regulation throughout the day. It makes heavy use of motor activities that can help expend energy and calm the child. A sensory therapist identifies a number of sensorimotor activities that fit the child’s needs and abilities. Every 90-120 minutes, the child’s teacher or parent selects 10-15 minutes of activities from the therapist’s set for the child to perform.

A sensory enrichment (SE) approach uses some of the same goals and types of interventions as the other two programs, but it is a flexible approach without a specified protocol. It covers a variety of intervention types. A sensory therapist selects activities, as well as duration and frequency of intervention, based on the child’s need for registration of input or sensory desensitization or immersion. Parents and teachers are given supplemental home/classroom exercises. Sensory enrichment can be used as a source of substitute activities for the other programs.

The table below lays out the differences among the three programs in terms of target population (children with or without autism), ease of implementation, flexibility, commitment from parents and teachers, and level of evidence.

|

Environmental Enrichment |

Sensory Enrichment |

Sensory Diet |

Target Population |

ASD |

Sensory or ASD |

Sensory or ASD |

Goals |

Increase attention to environment. Acclimate to environment. Reduce behaviors. |

Gradually increase child’s ability to modulate in the presence of sensory input. |

Train child’s brain and body to stay regulated. Decrease feeling of being overwhelmed. |

Focus on specific sense |

Many are covered, but primary focus is on combined scent and touch, sound, light touch and thermal. |

Focus is on the child’s most problematic sensory areas. |

Focus on movement strategies to provide calming, as well as input to other senses as needed. |

Ease of implementation |

Purchase materials and follow the protocol. |

Select activities based on child’s needs and interests. Exercises can be incorporated into daily activities. |

Therapist determines child’s sensory needs and finds suitable exercises. Caregivers select activities from a list. |

Number of interventions per day |

Two 20-30 minute semi-structured sessions. Optionally, two 1-minute scent immersion and a 15-minute music immersion. |

Not prescribed. 2-3 times per week, minimum. |

One 1—15 minute session every 90-120 minutes throughout the day. |

Flexibility |

Somewhat flexible. Set procedure, but flexible times. |

Very flexible. |

Flexible activities but set times. |

Compliance |

Somewhat demanding. Parents and teachers need to be well organized. |

Not structured. Caregivers and teachers may forget to perform activities. |

In an unstructured environment, parents and teachers find compliance to be difficult. |

Evidence |

Two studies show evidence with children with autism. Many animal model studies. |

Not studied as a standalone technique, but commonly integrated in effective feeding and Ayers Sensory Integration® techniques. |

Not sufficiently studied as a stand-alone technique. It is a component of Therapressure™ which has a “Level 2” evidence rating. |

A Note About Screening and Assessment Tools

A number of sensory modulation screening tools are currently on the market, and a new assessment (the Sensory Scales) is in trial. Sensory therapists typically screen with the Sensory Profile (SP), the Short Sensory Profile (SSP) or the Sensory Processing Measure (SPM). All three are parent and teacher questionnaires and are standardized and normed. As screening tools, they work well at identifying problem areas of SMD and related behavioral issues. However, they do not identify underlying issues in the sensory system. A side note: the SSP and SP are typically used by researchers to categorize the sensory makeup of their study population.

(A free informal checklist is available on the SPD Foundation website at http://www.spdfoundation.net/about-sensory-processing-disorder/symptoms/. This set of questions is not standardized or normed, but provides a starting point for determining sensory-modulation issues.)

Programs and Practice

When it comes to changing the way the body operates, OTs and PTs believe in exercise with lots of practice. Sensory therapists also agree that, in order to increase sensory processing and modulation skills, the child needs a regular program of activities. They can be loose or highly structured, yet they should be reasonably consistent. The challenge is to determine the optimum number of interventions in a day or a week. The standard practice for OTs and PTs consists of two in-clinic (or in-school) sessions per week with assigned at-home activities. The Environmental Enrichment protocol mandates two 15-30 minute exercise blocks each day. That was too much for 25 percent of the parents who dropped out of the study due to time constraints. (The remaining parents managed to facilitate their child’s program about 77 percent of the time, which was sufficient to produce significant results.) The Star Center, a sensory clinic in Denver, uses an intensive model with month-long, on-site treatment. They have reported excellent results.