Chapter 3

EATING FOR HEALTH

The Chinese concept of a balanced diet is different from Western concepts. It makes no mention of proteins, calories, vitamins, enzymes, and minerals. Instead, in China we refer to the flavors of foods, as well as to their qualities—the Yin/Yang and Five Element characteristics, and the food’s nature as hot, warm, cool, or cold. Although the foundational tenets are different, in the end a balanced diet in both cultures amounts to the same thing: a varied regimen that ensures the consumption of moderate quantities of all available nutrients. The major difference in the two approaches is that the Chinese balanced diet takes into account not only the qualities of food but also those of the person eating it. The climate and the time of year are considered as well.

As a consequence of this wider approach one cannot make a straightforward assertion about whether any one food—mutton or coffee or spinach, for example—is good or bad for you. The value of any particular food is relative to your individual characteristics and the climatic conditions. If it is winter and you have a cold, Yin constitution, mutton and coffee are good for you. They have Yang and warming effects that counteract your personal nature and the climatic conditions. Spinach, on the other hand, is cool and may not be the ideal food for you in winter.

Before getting involved in more specifics regarding individual conditions and needs, let us look at some of the general do’s and don’ts of Chinese preventive diet in regard to what and how, as well as when to eat.

It is probably worth recalling the “five forbiddens” listed in chapter 2. These are:

- Refrain from monotony. Do not eat only what appeals to your palate. Vary your diet at every meal.

- Avoid excesses. Eat spicy, sour, fried, salty, and sweet food sparingly.

- Never eat large amounts at a single sitting. You should rise from the dinner table feeling only two-thirds full. Overeating leads to stress on the digestive system, inefficient absorption of nutrients, weak qi, and disease. Three light meals a day is the ideal. However, if you are very physically active and require more calories, several snacks through the day is better than one or two large meals.

- Beware of exotic foods such as snake meat, scorpion, insects, bear paws, snails, and the like. These foods have their functions for some specific ailments but should not be eaten just for the sake of taste.

- Do not overindulge in beverages instead of solid food. If you can do so comfortably, you should not drink at all during meals. The intake of liquids dilutes gastric juices and impairs digestion. Take your liquids before or after mealtimes.

Other rules are not even mentioned because they are simply common sense daily practices. These might be called the five obvious forbiddens. They are:

- Do not eat too little for your body weight and energy expenditure.

- Do not take toxic, contaminated, stale, rotting, or cold food or drinks.

- Do not fry your food. If you must use oil, stir-fry briefly in a wok, or add a little raw oil to steamed or boiled food or to your salads.

- Do not overcook your food. Overcooking destroys its heat-sensitive nutrients (enzymes and some vitamins).

- Do not overindulge in alcoholic drinks. One beer, one glass of wine, or a single shot of spirits a day appears to have a positive effect on health. Anything more than this is poison.

Following the guidelines regarding what (and how) not to eat will in and of itself lead to better overall health. The customary Chinese way of eating is to serve small portions of many different foods. A traditional Western meal consisting of soup, steak, fried potatoes, and a dessert would be considered by the Chinese to be not only unhealthy but uncouth as well. First of all, there is not enough variety in the menu. Second, we believe that soup should come at the end of the meal (instead of a sweet dessert) in order to wash away strong flavors.1 Third, most Chinese don’t relish the idea of eating a slab of meat. We feel it cannot be cooked properly: either the outside is burned in order to cook the center, or else the inside is eaten raw—which for most Chinese people is too horrific even to contemplate. The only way we cook meat in China is to cut it into pieces. The origin of this practice was to save cooking fuel; however, it also ensures uniformity of cooking, as well as the possibility of sharing with others. Which brings us to our final point: eating individual portions is considered downright antisocial. And eating alone is abhorrent to most Chinese people: it is something that you do in a hurry, consuming perhaps your leftovers from a “real meal.”2 In China, people like to eat together; they like the hot and noisy atmosphere. And the more people there are, the more dishes and the more variety. The point, therefore, is to eat a little of a dozen or so food items at each sitting. A Chinese meal usually starts with a variety of cold dishes: boiled peanuts, ginger, raw tomato, cured jellyfish, bamboo tofu, germinated soybean shoots, and various cuts of cold meat. This is followed by alternating flavors and properties (warm, hot, cool, and cold) in the main dishes. Thus a dish of chicken (sweet [Earth] and warm) cooked with walnuts may be followed by spicy tofu (sweet [Earth] and cool) with hot and pungent [Metal] red pepper, by lettuce leaf in oyster sauce (cool and bittersweet [Fire and Earth]), and by shrimp with garlic (warm and sweet [Earth], balanced by the pungent (Metal) garlic—which, incidentally, also counteracts the cholesterol intake from the shrimp). The meal might proceed with green stringbeans, celery, and black mushrooms (all of which are sweet [Earth] and thermally neutral, with a dash of bitter [Fire] from the celery). If you had crab (cold and salty [Water]), you would eat it cooked with dry ginger (hot and pungent [Metal]) and vinegar (sour and bitter [Wood and Fire]) for balance. Finally, you would have either a bowl of rice or some steamed bread and a clear broth to wash it all down with.3

In China, everything is eaten: vegetables, fruits, seeds, roots, berries, fish, fowl, and all manner of four-legged creatures. A few purists argue that eating meat is harmful because it contaminates your vital energy with the grosser (that is, lesser refined) qi of animals; they, and Buddhist monks, are probably the only people in China who do not eat moderate quantities of meat fairly frequently. Yet meat is not the kind of health hazard in China that it is in the West. It is still seen as too much of a luxury to be overindulged in, and even those people who can afford it are aware of the dangers.4

Food should be consumed as soon after harvesting as possible, as some vitamins are dissipated in time. People in China make a point of shopping every day. Many families do not have refrigerators or freezers, and those who do possess a refrigerator do not keep food in it for more than a day. Indeed, the purpose of a refrigerator often has more to do with showing off one’s new status symbol—or, for the more practically minded, for cooling drinks in summer—than with food preservation. Freezing destroys vitamin C, and canned food often consists of pure bulk, with no enzymes or vitamins. Canned food can also be contaminated by megadoses of preservatives and other toxins. For these reasons it is best to eat all foods as fresh as possible.

HOW TO EAT

Moderation is the key not only to what you eat but to how you eat. The following guidelines should help you stay conservative in your intake.

- Eat only when you are hungry.

- Three meals a day are supposed to be most conducive to good health. Start with a large breakfast, follow it with a medium-sized lunch, and end the day with a light dinner at least three hours before bedtime. In China the evening meal is rarely taken much later than 7 P.M.

- Never eat when you are angry, upset, or in a state of emotional turmoil. Extreme emotions, considered to be one of the causes of disease, interfere with digestion.

- Eat slowly. Chopsticks elegantly used ensure that your food cannot be eaten too rapidly—by “elegantly used” we mean picking up each morsel and carrying it from your bowl to your lips.

- Chew your food properly and relish your drinks. Or, as the Chinese saying goes, “Drink your food and chew your drinks.”

- Eat your food at room temperature if raw, or warm if cooked. Never eat food directly out of a refrigerator or piping hot. Extremes in heat and cold are a shock to the body.

- Do not talk when you eat. While people in China like to eat in large groups, they generally save their conversations for the time between courses.

- Eat in a warm and comfortable environment. Do not eat outdoors with your face into the wind; cold air is said to enter your body every time you open your mouth, causing stomachache.

- Avoid being sedentary immediately following a meal. A popular Chinese saying claims that “one hundred steps after meals assures ninety-nine years of life.”

WHEN TO EAT VARIOUS FOODS

Other than the actual foodstuffs, climate and time of year are perhaps the most important considerations for someone intent upon maintaining good health through conscientious eating habits.

According to traditional Taoist medical theory, one of the main causes of disease are the exogenous pathogens: the climatic aberrations of evil wind, excessive cold, heat, dampness, dryness, and firelike heat. These pathogens are believed to enter the body and cause havoc with one’s equilibrium. The flow of zheng qi is affected, the internal organs are weakened, the individual’s personal constitution is thrown out of skew, and illness is the likely outcome.

Because of the interdependence of all nature, the cold and heat that can attack a person from the outside also exist within each one of us as part of our individual constitution—we may be hot, cold, dry, damp, excessive, or deficient physical types. They also exert their influence as warming, heating, cooling, and cold characteristics of everything we eat.

It follows therefore that, when in the depth of a cruel northern Chinese winter a person curls up on a warm kang and considers what to have for dinner, he does not think of salads, seafood, and watermelon, all of which are cold foods.5 Hot ginger soup, warm chicken, chestnuts, and a dried peach are more likely choices. While this may sound like common sense, because anything and everything is available year-round in Western supermarkets people often make what, in Chinese eyes, would be considered very poor food choices given personal temperament and time of year.

It is important for one’s health to eat according to season. Foods that are either slightly warming or cooling and those that are thermally neutral can be consumed without ill consequence during any season. Foods that exert powerful heating or cooling effects should not be consumed in the “wrong” season lest they exacerbate the influence of the pervading climate. However, taking cold food in summer will ensure greater resistance to summer heat. Hot foods in winter, on the other hand, protect against the cold.

Often, distinguishing between hot and cold foods is a matter of intuition or common sense. Nobody would consider black or white pepper cooling, nor would most people regard watermelon as warming. Often, however, we might be in doubt as to the thermal effects of bananas, crabs, or clams (all cold foods), or soybean oil (a hot food). We have therefore drawn up a list of cooling, cold, warming, and hot foods to help guide you in developing your awareness and making proper food choices. It is useful to remember that hot and warm thermal characteristics always correspond to Yang, and that cold and cool foods are always Yin.

Yin Foods

Cooling: apples, barley, tofu, mushrooms, cucumber, eggplant, zucchini, lettuce, lamb’s liver, loquat, mandarin orange, mango, marjoram, mung bean, oyster shell, pear, peppermint, radish, sesame oil, spinach, strawberries, tangerine, wheat (and bran), fresh nonmatured coconut, yogurt, tea, jujube, rosehips.

Cold: bananas, grapefruit, melon, watermelon, persimmon, sugar cane, tomato, water chestnut, bamboo shoots, bitter gourd, lotus seed, egg white, clam, crab, kelp, seaweed, salt.

Yang Foods

Warming: apricot seed, asparagus, brown sugar, butter, caraway, fish, cherry, chestnut, chicken, chive, cinnamon twig, clove, mature coconut, coffee, coriander, cuttlefish, dates, orange, tangerine, grapefruit or mandarin peel, eel, fennel, garlic, fresh ginger, ginseng, green onion (scallion), guava, ham, kidney, liver, kumquat, mustard, leek, longan, lychee, malt, meat, milk, mussels, nutmeg, peaches, raspberries, rosemary, shrimp, spearmint, pumpkin, anise seed, sunflower seed, basil, rice, broad beans, vinegar, walnuts, wine, alcohol.

Hot: cinnamon bark, dried ginger, black or white pepper, red or green pepper, soybean oil, pork and greasy meats, cream, cocoa, chocolate, butter.

PERSONAL CONSTITUTION

Every individual has his or her personal characteristics in terms of body build, Yin and Yang, hot and cold, damp and dry, and excessive or deficient constitution. The relations and imbalances between these factors are wholly individual in nature. It therefore becomes important, when balancing your diet, to be aware of your personal characteristics so that abundant qualities are balanced and deficient qualities are enhanced.

A thin person of reddish complexion who prefers cold drinks and food to hot is generally considered to be a preponderantly hot (Yang) physical type. A plump person who is seldom thirsty and prefers hot drinks to cold is said to be of the cold, Yin type. Heavily built, lethargic people are damp (Yin) in character. Wiry individuals who are forever thirsty and suffer from dry skin, hair, nose, and mouth are considered dry (Yang).

The descriptives used to classify a person as hot or cold, damp or dry, deficient or excessive are similar to the classifications of the wai yin (external pathogenic) disease syndromes discussed in chapter 2. The same words are also used to describe the nature of various foods. Good health is seen as the balanced interplay between these properties in the environment, in the human body, and in food and drink. For example, the tall, thin person of ruddy complexion—the Yang, hot and dry characteristics mentioned above—will achieve optimum health by balancing his or her natural tendencies with Yin cold and lubricating foods, such as banana, grapefruit, orange, mango, pear, persimmon, strawberry, watermelon, lettuce, celery, tomato, seaweed, milk, honey, egg, and seafood (except shrimp). If, on the other hand, this person should eat large quantities of meat, scaly fish, or strong Yang foods that are spicy, hot, or salty, he would begin to suffer from lack of energy, indigestion, and eventually from imbalances that lead to illness.

The damp, heavily built person would do well to consume plenty of warm Yang foods: apricot, cherry, lemon, lychee, longan, papaya, raspberry, peach, chestnut, garlic, ginger, fennel, green onion (scallion), radish, peanut, potato, grains (brown rice and bread), beans, shrimp, and a little wine. Large quantities of dairy products, fats, and meat would increase the lethargy and convert into body fats.

Finding your personal body type is a multifaceted exploration. There are several factors to consider beyond build. These include your body heat, your moods and dispositions, your sex drive, and others. No person is exclusively one physical type. Furthermore, energy levels, moods, and the climate change all the time, affecting your physical condition. It would be ideal to consult a Chinese physician for a professional opinion regarding your overall Yin or Yang nature and whether your bodily constitution is essentially hot, cold, dry, humid, excessive, or deficient. However, self-observation aided by the following questionnaire should allow you to make a fairly precise assessment of your underlying physical characteristics.6

PERSONAL CHARACTERISTICS QUESTIONNAIRE

Give yourself one point for each question you answer in the affirmative, two points if you feel that the question suits you particularly well.

YIN

If you are a woman, give yourself two Yin points.

Do you consider yourself feminine?

Are you timorous?

Are you the indoor type?

Do you tire easily?

Do you consider yourself lazy?

Do you fall asleep easily when traveling by plane, train, or bus?

Are your hands often cold?

Are your feet often cold?

Do you prefer the cold of winter to the heat of summer?

Are you overweight? (If you answer yes, score one point for every ten pounds over the normal weight for your sex and build.)

Is food better than or just as interesting as sex?

Do you consider your sex drive to be weaker than normal? (Give yourself two points if you answer in the affirmative.)

Cold constitution

Do you rarely feel thirsty?

Do you generally prefer hot drinks to cold ones?

Is your complexion usually pale?

Is your urine normally plentiful and clear?

Are your stools normally soft?

Is your tongue usually pink with no coating?

Do you suffer from muscular or joint pains in cold weather?

Damp constitution

Do you often feel tired?

Are you overweight?

Is your complexion usually dull?

Are you often sad or depressed?

Do your palms sweat?

Is your tongue usually glossy or greasy?

Do your joints ache when it’s raining?

Deficient constitution

Are you often low-spirited?

Are you often tired?

Are you skinny or underweight?

Do you sweat a lot?

Do you sometimes suffer from heart palpitations?

Are you of pale or pallid complexion?

Is your tongue white or light pink without coating?

YANG

If you are a man, give yourself two Yang points.

Do you consider yourself masculine?

Are you generally self-confident?

Are you the outdoor type?

Can you work for long stints without tiring?

Do you consider yourself energetic?

Do you find it difficult to sleep when traveling by plane, train, or bus?

Are your hands often hot?

Do your feet sweat?

Do you prefer the heat of summer to the cold of winter?

Are you underweight? (If your answer is yes, score one point for every ten pounds below the normal weight for your sex and build.)

Is sex better than food?

Do you consider your sex drive to be higher than normal? (Give yourself two points if you answer in the affirmative.)

Hot constitution

Do you normally prefer cold drinks to warm or hot ones?

Is your complexion generally reddish?

Is your urine usually scanty and of a reddish or yellow hue?

Are you often constipated?

Are your stools usually dry?

Is your tongue normally red with a yellowish coating or no coating?

Do you suffer from frequent skin eruptions?

Dry constitution

Are you often thirsty?

Are your nose, throat, and skin usually dry?

When you catch cold, is your cough usually dry without mucus?

Do your eyes and nose often itch?

Is your tongue frequently parched and dry?

Is it difficult for you to gain weight?

Are you often constipated?

Excessive constitution

Are you usually full of energy?

Do you consider yourself to be normally high-spirited?

Is the tone of your voice high-pitched?

Is your complexion usually flushed?

Is your blood pressure higher than normal?

Are you restless and impatient?

Do you suffer from constipation?

When you have completed the questionnaire, first add only your scores under the two main headings Yin and Yang; do not include your cold, damp, deficient, hot, dry, and excessive constitution scores in your first tally. The first total will tell you your predominant Yin/Yang characteristic. Few people are ever wholly Yin or Yang, so even if you are an energetic, self-confident male who enjoys sex and the outdoor life, it does not mean that you will have a score of 0 in the Yin section.

Now add up your bodily constitution scores. Once you have these tallied, add the cold, damp, and deficient numbers to your Yin scores; then add the hot, dry, and excessive numbers to your Yang scores. In the end, most people will find themselves scoring more or less equally on both Yin and Yang.

The point of this exercise is simply to be aware of your general tendencies. You will then be in a position to correct any imbalances in your constitution before they begin to affect your health. However, before you go about making drastic changes to your eating habits, you must first bring the Yin or Yang effects of climate into your calculations. If you have a 24 Yin score and a 17 Yang, for example, you might be tempted to include ginger, garlic, or onion in your diet for their warming effects. If it’s the middle of summer, however, eating warming foods such as these would be a mistake—summer heat on its own counteracts any Yin or cold tendencies in your body. To further increase the heat with ginger and garlic would overbalance you in the opposite, Yang, direction.

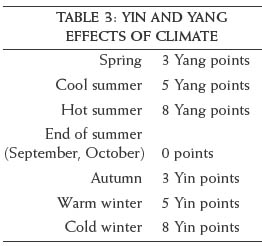

In order to bring climatic effects into your personal Yin and Yang scores, add points according to the season, as shown in the following table.

If, in the final analysis, you find that your Yin and Yang or your body constitution scores are significantly different, all it means is that you should try to include a little more balancing food in your diet in proportion to the differences. Increase your intake of Yin or Yang, warm or cool foods by 10 percent for every five-point spread on the overall Yin/Yang scores. Try also to include more hot and warming foods in your diet if the questionnaire indicates you are of cold, damp, or deficient constitution, or if it is winter; conversely, eat a little more cold or cooling food if you are the hot, dry, or excessive physical type, or if it is summer.

It should be clear by now that Chinese theories of health offer few simple do’s and don’ts regarding diet. Health-giving food choices depend on personal constitution, the time of year, and the nature of disease a person might be suffering from. Only when you have a clear picture of your personal health needs can you choose your diet with confidence, noting the warming or cooling properties of foods, their taste and Element, and whether they lubricate or constrict. To help you in growing more discerning, the following chapter, Foods and Their Healing Properties, details the properties (in Chinese terms), vitamin and mineral contents, and usage of many foods commonly employed in Chinese therapeutic cuisine.