Chapter 7

EXERCISING FOR HEALTH

Everybody in China exercises. School children exercise collectively once a day. Adolescents and young adults go in for wushu and Shaolin boxing. Parents jog, swim, walk, bicycle, and swing weights. Grandparents perform early morning tai ji quan or take a radio to a park for a spot of geriatric disco dancing. Great-grandparents twirl metal spheres in the palms of their hands to exercise their fingers (and the acupuncture points on the hands) or swing their pet canaries’ cages as they stroll in the park. But the exercise everybody recognizes as the best for overall fitness and health is one that the Chinese people have been practicing for at least three thousand years. It is qi gong.1

Qi corresponds to the Sanskrit word prana and the Greek pneuma; it means “breath,” or “breath of life.” The word also refers to material energy, vital matter, the earth’s atmosphere, or the fundamental substance of material beings. The word gong translates as “mental control over the body.” Qi gong thus means “mental control over the flow of qi in one’s body. “

Various techniques for exercising control of qi have developed over the centuries. Many of these techniques are medical; others branched out into various disciplines of martial arts. There are Buddhist techniques, Taoist techniques, and Confucian techniques. Fundamentally, however, qi gong may be divided into two basic methods of exercising: nei dan and wai dan, which respectively mean “internal elixir” and “external elixir.”

Nei dan, or internal qi gong, consists of breathing deeply while concentrating on circulating qi inside the body. Wai dan, or external qi gong, is the practice of stimulating certain areas of the body by means of movement and exercise so that qi builds up and flows outward.

NEI DAN QI GONG

In China it is said that where the mind focuses the qi will follow. Therefore, during nei dan the mind focuses the incoming breath and sends it to the dan tian, the center of all bodily energy, thought to be situated in the lower abdomen. The abdominal muscles are strengthened by the breathing exercises, and more energy is generated. When sufficient qi has accumulated in the dan tian, the mind directs this energy through the two major qi channels, the ren mei and du mei, which are said to be situated at the front and back of the torso respectively. This practice is referred to as the small circulation of qi, or xiao zhou tian. When one is proficient at the small circulation technique, one may then generate stronger qi that is made to flow through all twelve energy channels in the body and limbs in what is known as the da zhou tian, or grand circulation. This is said to result in perfect fitness and health.

The first step in the above exercise is to find a good position that allows for correct abdominal breathing. According to some teachers, the best position for practicing internal circulation of qi is sitting with legs crossed. They explain that it is useful to keep the legs crossed because, when you are trying to circulate the qi around the torso (in the small circulation exercise), it can easily go shooting off down your legs unless you obstruct the entrance to the lower channels in the legs by crossing them.

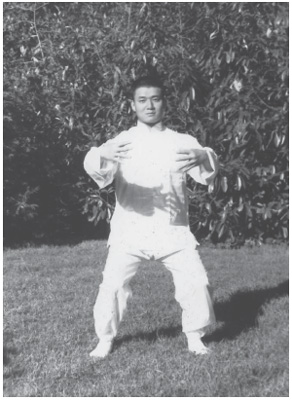

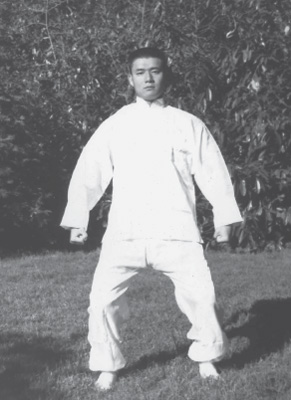

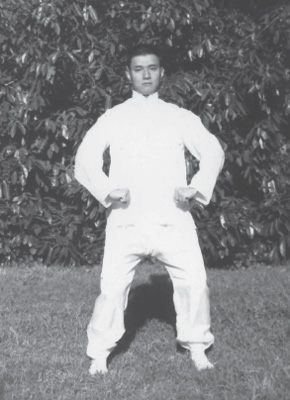

Later, when the grand circulation is attempted, qi is supposed to flow through all the limbs. Therefore, a standing position becomes necessary. This position is the one most frequently used by practitioners of qi gong in China (figure 1).

Figure 1

Stand with your feet shoulder-width apart, toes pointing slightly inward. Bend your knees slightly, as if you were about to sit down; the weight of your body should be on your feet and lower legs, not on your thigh muscles. Hold your back and neck straight and raise your arms, bending them at the elbows, as if to encircle a large balloon. Your fingers should be splayed in this same balloon-encircling position. Do not raise your shoulders. Your body should feel relaxed and comfortable.

This position strengthens the muscles of the back, legs, arms, and abdomen. Take care, however, not to overexert yourself in the beginning. The position may look easy but, because of the unusual angle of the legs, a good deal of strain is put on the thighs as well as on the arms. Ten minutes of this position can leave one feeling quite weak. Gradually increase your time spent in the position.

Xiao Zhou Tian (Small Circulation Abdominal Breathing)

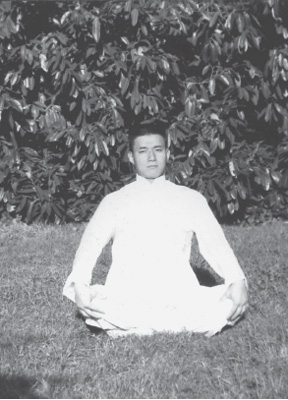

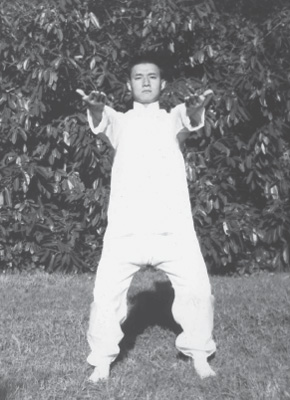

There are two techniques for xiao zhou tian abdominal breathing—one is Buddhist and the other Taoist. Both employ a cross-legged seated pose (figure 2), although with experience they may also be done standing.

Figure 2

The Buddhist technique consists of focusing on the abdomen while breathing slowly and uniformly through your nostrils. Expand your abdomen as you breathe in; contract it as you breathe out. Do not hold your breath.

The Taoist technique is the opposite of the Buddhist. You concentrate on your abdomen, as above, but you contract it when you inhale and expand it when you exhale. This Taoist breathing technique also goes by the name of fan hu xi, or reverse breathing.

Abdominal expansion should never be forced, but should be perfected gradually, with gentle daily practice, until you can expand your abdomen from your navel to your pubic bone.

Once this has been achieved you should sit in quiet meditation, concentrating on your breathing. Imagine the breath traveling through your nose and down to the dan tian, as if you were swallowing something and you could feel it descending all the way to your navel. After a few sittings you should begin to feel a tingling sensation and warmth in the abdominal area. This means that your qi has accumulated sufficiently and that you are now ready to attempt the circulation aspect of the exercise. This is done by guiding the qi around your torso with your mind. At first it will only be a question of imagination and little qi. With time, however, the flow of qi will become stronger and thus more perceptible.

Begin by guiding your qi in the following breathing sequence:

- Close your mouth and eyes. Press your tongue against your palate. Inhale and guide the incoming qi through your nose and down to the dan tian. Tighten your anal sphincter muscles during the inhalation.

- Exhale and guide the qi from the dan tian through the groin and into the cavity in front of the coccyx, or tailbone. This is called the wei lu cavity. Relax your anal sphincter as you exhale.

- Inhale and guide the qi to the base of your neck, between your shoulders.

- During the final exhalation, guide the qi from the back of your neck to your ears, and then down to your nose and mouth. When the qi enters your mouth, relax your tongue from its position against the roof of your mouth.

One full cycle of xiao zhou tian thus includes two respirations.

You should continue the small circulation exercise for ten minutes two or three times a day. After three months of regular practice you should be ready to go on to the grand circulation exercise.

These exercises are beneficial to the lungs, abdominal viscera, heart, and nervous system.

Da Zhou Tian (Grand Circulation Abdominal Breathing)

You are ready to go on to the da zhou tian only when you are confident that you are able to circulate qi around your torso, as in the small circulation exercise. Evidence that you are able to do this correctly consists of a feeling of warmth in all the areas of your body through which your qi is being guided by your mind.

Your pose for the first phase of the grand circulation technique should be either sitting in a chair or standing, preferably in the qi gong standing position. Your thumb and little finger should be touching.

- Breathe in while contracting your abdomen (or expanding it, if you prefer the Buddhist method of respiration). Guide the qi from your nose to the dan tian. Tighten the anal sphincter muscles.

- Exhale and guide the qi to the wei lu in the coccyx. Relax your sphincter muscles.

- Inhale while guiding the qi to the back of your neck, between the shoulders.

- During the final exhalation do not guide the qi over the top of your head to your nose as previously, but direct it from the shoulders to your hands and fingers.

Repeat this cycle through several sittings until you feel a warm flow of qi to the center of your palms.

In order to guide the flow of qi to your lower limbs, the usual procedure is followed except that you should adopt a supine position. By lying down and relaxing your leg muscles, the qi is said to flow with greater ease. A standing position will not obstruct the flow of qi completely, but simply constrains the channels a little more.

- Breathe in as before, guiding the qi from the nose to the dan tian. Exhale and guide the qi through your groin, down your legs, to the center of the soles of your feet.

- On your subsequent inhalation and exhalation, take the qi up your back and over your head to your nose.

You know that the da zhou tian has been achieved when you are able to feel the warmth of the flowing qi both in your hands and your feet. Your feet may feel hot and numb for several days after you have successfully directed your qi to them. However, do not expect results too quickly. It will take months, at least, to circulate your qi successfully to your hands and feet. Later you will be able to guide the qi to both your hands and feet simultaneously, and direct the qi to any part of your body at will. You will not only be able to cure your own ailments, but you will be able to expand your qi beyond your own body, transmitting it to others and thereby healing their illnesses.

After completing a session of nei dan qi gong, most people need to release some of the energy they have been controlling. This can be done through massage of the limbs, face, and head, or by means of movement exercises such as stretching, turning the head from side to side, or rotating the shoulders.

WAI DAN QI GONG

Most people prefer to train the qi by means of external elixir techniques, or wai dan. Wai dan qi gong does not have to follow nei dan breathing techniques. It may be practiced before them or entirely independently.

Wai dan qi gong techniques involve many complex movements that are not easy to learn from a book. To try to do so would inevitably lead to mistakes in practice. Without a qualified teacher’s guidance, a student cannot know if his posture, his sequences and his speed are correct. Schools of martial arts exist in most towns and cities in America. If you would like to take your study of Oriental breathing techniques further and to practice wai dan qi gong, you should enroll in one of these courses.

However, a short description of one of the earliest forms of wai dan qi gong will do no harm. This practice was taught by the Indian Buddhist monk Bodhidharma, who traveled to China in the sixth century A.D.2 Bodhidharma was called Da Mo in China, hence the name of this exercise.

When Bodhidharma settled in the Shaolin Buddhist monastery in Henan province in central China in 527 A.D., he is said to have been shocked by the emaciated condition of the local monks. As a consequence, he taught them a series of twelve drills based in Indian yoga that ensure fitness and build muscular power as well. These basic drills were later elaborated upon by future generations of monks until they became the world-renowned wushu (literally, “martial” [wu] “art” [shu]) system of Shaolin boxing, also known in English by the Cantonese term kung fu.

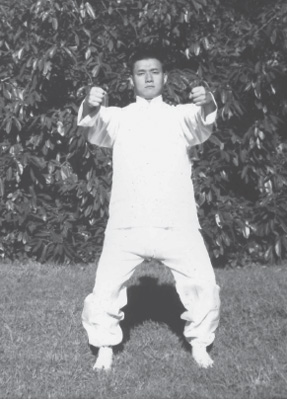

The twelve exercises of Da Mo wai dan should be performed in sequence. Each drill consists of at least twenty breaths—energy is built up by relaxing a muscle during inhalation and tensing it during exhalation. By performing the exercises in sequence, the energy built up in one exercise is carried forward to the next. The full sequence of twelve exercises should take about fifteen minutes. Longer sittings would include as many as fifty breaths per drill.

Throughout the Da Mo wai dan exercise you should stand straight with your feet parallel to one another, about twenty-four inches (45 centimeters) apart.

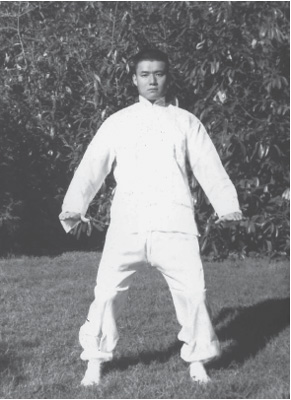

Exercise 1

Stand with your feet approximately two feet apart. Hold your arms by your sides, your elbows slightly bent and your palms open toward the ground (figure 3). Your fingers should be pointing forward. Inhale slowly and uniformly. Exhale and imagine pressing firmly downward with your hands. In this exercise qi is built up in the wrists.

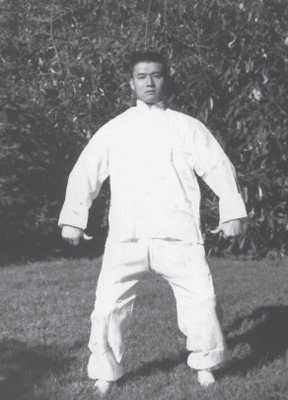

Exercise 2

Maintain the same position as in exercise 1. Close your hands into fists with your thumbs extended toward your body (figure 4). During exhalation imagine tightening your fists and pushing backward with your thumbs. In actual fact, your wrists should only be slightly tensed.

This exercise builds up energy in your hands and fingers.

Exercise 3

Maintain the same position as in exercise 2. Close your thumb over your fingers, making a fist. Turn your fists so the inside of your wrist faces your body (figure 5). Inhale. Then imagine tightening your fists, and exhale.

This exercise builds up energy in the whole of the lower arm.

Figure 3

Figure 4

Exercise 4

Keeping your fists clenched, extend your arms in front of you, the insides of your wrists Figure 3 facing inward (figure 6). Imagine firmly clenching your fists during your exhalation.

This exercise builds qi energy in your chest and shoulders.

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

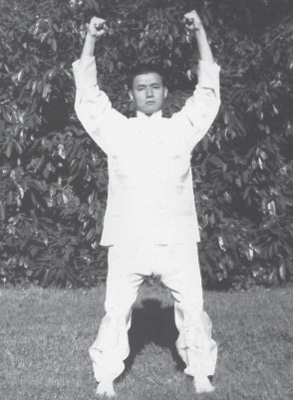

Exercise 5

Now raise your arms further until they are straight above your head. Maintain the fist position of your hands (figure 7). Imagine clenching your fists while breathing out.

This exercise builds qi in the shoulders, the neck, and the flanks.

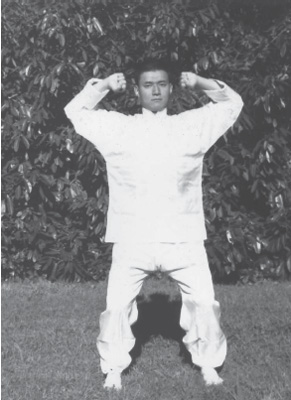

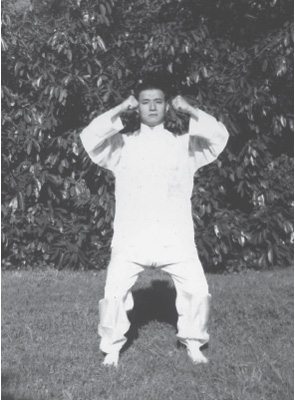

Exercise 6

Bend your elbows and lower your fists to within six inches of your ears. The insides of your wrists should be facing forward (figure 8). Inhale slowly. Exhale and imagine clenching your fists.

This exercise builds qi in the flanks, the upper torso, and the arms.

Figure 8

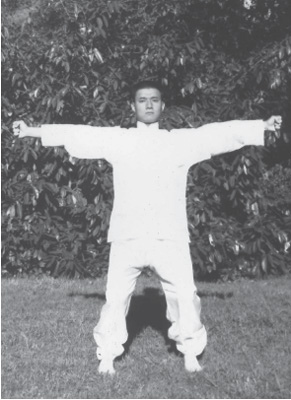

Exercise 7

Keeping your fists clenched, extend your arms sideways, parallel to the ground. The insides of your wrists should be facing forward (figure 9). Inhale. Exhale and imagine tightening your fists.

In this exercise, qi builds in the upper torso.

Figure 9

Exercise 8

Bring the extended arms forward. Bend your elbows slightly, giving a circular effect to the position of your arms (figure 10). Imagine clenching your fists during exhalation.

This exercise builds qi in the arms and shoulders.

Figure 10

Exercise 9

Pull your clenched fists back from the previous position, toward your face. Bend your elbows and hold your fists, palms forward, just in front of your cheeks (figure 11). Imagine tightening during your exhalations.

In this exercise, qi is further enhanced in the arms and shoulders.

Figure 11

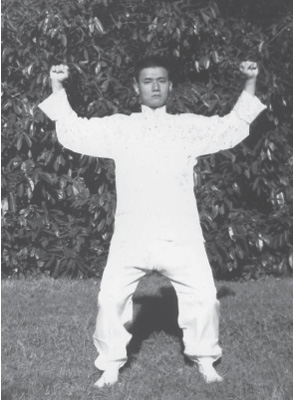

Exercise 10

Pull your elbows back and raise your forearms so that your fists are held about one foot from either side of your head (figure 12). Imagine clenching your fists during your exhalations.

This exercise is designed to start circulating the qi accumulated in your shoulders.

Figure 12

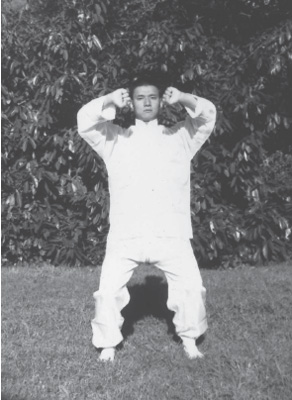

Exercise 11

Keeping your elbows bent as in exercise 10, lower your fists to a position immediately in front of your dan tian, about four inches (10 centimeters) below your navel (figure 13). Imagine clenching your fists during your exhalations, and mentally guide the qi through your arms.

In this exercise qi is no longer accumulated. Instead, the qi already in your body is gathered, and directed to flow through your arms.

Figure 13

Exercise 12

Unclench your fists, straighten your elbows, and raise your arms straight out in front of you. Hold your palms facing skyward (figure 14). When exhaling imagine lifting a heavy weight with your arms.

Figure 14

In this exercise, qi is recovered for redistribution around the body.

When you have completed the whole wai dan sequence, it is good to relax for a few minutes, either seated or lying down, breathing normally.

Da Mo wai dan qi gong strengthens the body as a whole, and the muscles, joints, and inner organs in particular. These exercises also improve circulation. They ensure the equilibrium of the nervous system, and build up resistance to disease.

There are many other popular wai dan exercises that have derived directly from Bodhidharma’s original sequence. One well-known sequence of eight drills, called ba duan jin, or Eight Pieces of Brocade, was created by a famous patriotic general, Yue Fei, in the twelfth century, to maintain fitness in the ranks. Yue Fei’s ba duan jin was based on an earlier series of exercises by the same name devised by Zhong Li during the Tang dynasty (618–907 A.D.). Other versions of the ba duan jin have been developed over the centuries, some during the last forty years as qi gong started becoming fashionable. Another well-known sequence of qi gong exercises is tai ji quan, an intricate sequence of movements during which the mind guides qi around the body.3

Qi gong is becoming ever more popular in the West. Tai ji quan and qi gong lessons are now standard in many health clubs. Together with the increased acceptance of Chinese physical exercise, other aspects of Chinese health systems are also entering Western consciousness. Acupuncture has been used for years in alternative health circles, but is now entering mainstream medical practice. The use of Chinese herbal medicine is becoming increasingly common, to the extent that many allopathic doctors and researchers express interest in discovering the curative properties of these herbs and medicines. Chinese medical theory and practice may still be dismissed by conservatives as mere quackery. Other people extol Chinese traditions beyond all scientific reasonableness, sometimes suggesting curative effects that verge on the miraculous. As is usually the case, the truth lies somewhere between these two extremes.

Chinese traditions spanning millennia cannot be dismissed offhand. Enough empirical and experimental evidence exists to demonstrate that Chinese medical traditions are still valid today. On the other hand, Chinese medicine does not invariably provide a cure whenever Western medicine fails to deliver. What Chinese traditions of healthy living can assure us is that, if we carefully follow their precepts, we can stay healthy and youthful for many years to come.