Chapter 2

Investment Counsel

As we have already seen, John Templeton’s investment career falls into a number of distinct, but overlapping, phases. In this chapter, we concentrate on his early career as an investment counselor, which broadly spans the two decades between 1940 and 1960. Although this period of his life was to make him a wealthy and respected businessman in the United States, one who appeared more than once in the pages of the business press, it was not until the 1970s, when he was already in his sixties, that he was to become globally known and respected as a figure of substance in the international investment business.

His early professional years, before he moved into the higher profile and more profitable business of fund management, are nevertheless full of interest. It was during this period that many of the ideas with which he is now widely associated were first formulated, as can be seen in the internal memos and letters that he sent to the firm’s clients. A small selection of these is reproduced, in full or in part, in this chapter. More examples are reproduced in the appendix. Although written more than 50 years ago, the clarity of thought and expression that they display provide some fascinating clues to the character and intellect of their author. However rapidly the world may change, the fundamentals of sound investment remain the same from one generation to the next.

As far as we know, John Templeton’s decision to become an investment counselor had already been made by the time he completed his undergraduate studies at Yale University. It was not until two years after his return to the United States from Oxford that he was able to take the first steps toward achieving his professional ambition. An investment firm bearing his name was, it seems, first set up in 1938, while he was still employed elsewhere. By his own account, his first big break came when he bought a small investment advisory business in New York for $5,000, thereby getting his name on the door for the first time and moving into an office in Rockefeller Center. Two years later he merged this business with another investment counseling firm to create a new firm, Templeton, Dobbrow & Vance. Soon afterward, although he maintained the Rockefeller Plaza address, in order to save money he moved the bulk of the firm’s employees and operations to the suburb of Englewood, New Jersey, about nine miles north of Manhattan and a 45-minute distance by train and subway. Englewood was also where he and his wife lived.

For the next 20 years, he and his partners in this investment advisory partnership succeeded in building a growing and profitable business, looking after the money of a wide range of clients, principally wealthy families, estates, and trust funds. The firm in due course added a number of colleges, corporations, foundations, and institutions to the client list. It also was active in promoting the merits of profit sharing plans to companies. Templeton’s 80 percent shareholding in the partnership was funded initially by a combination of his savings and by the gains on his stock market portfolio, which, so he later recalled, enabled him to survive during the firm’s first five years without the need to draw an income every month.1 In a memo about the firm that he circulated to clients and friends in 1957, he listed what he regarded as the firm’s most important achievements.

1. Gross income has increased 25-fold in 16 years.

2. Net worth has increased more than 20-fold in 16 years.

3. Personnel has increased six-fold in 16 years.

4. From its beginning in one city only, the organization now works throughout the United States and Canada, with offices in five cities.

“We prefer to think of this organization,” he went on, “more as a sort of family than as a corporation. The group of partners and clients is closely knit and can still be thought of as a family, although it has grown from nothing to become of the 10 largest investment counsel companies in the nation. The company began 18 years ago for the purpose of providing assistance of unequaled quality for investors. The growth has been consistent and steady year after year.” This growth was attributable, he claimed, to the fact that the firm had helped its clients to achieve both “good results and peace of mind.” The good results, in turn, were largely the result of two policies in which our work has been “different from that of others, namely (1) emphasis on the importance of practical, long-term investment planning and (2) security analysis which is quantitative and systematic.”

As events turned out, Templeton had spotted an opportunity well ahead of many of his peers. In the same memo, he pointed out that the profession of investment counselor had been new and barely known to the wider public when he started out. Before the advent of investment counsel, most financial advice had been offered by brokers, investment banks, lawyers, and other professionals, none of whom were free of conflicts of interest, the besetting problem of the financial services industry (then as now). An investment counselor, by contrast, as he saw it, could provide a uniquely dispassionate form of help not previously available anywhere in the world, which Templeton summed up in these six words: “confidential, unbiased, expert, continuous, conservative, and personalized.”

This fledgling new profession received an early boost in 1942, when the Internal Revenue Service in the United States agreed to allow the fees for investment counsel to be deductible against tax for the first time. By the 1950s, buoyed by the continued postwar expansion of the American economy, the new profession was growing sufficiently fast to justify forming its own trade association, in which Templeton took a leading role. It appointed an early exponent of public relations to help promote its advantages to potential clients. Templeton and his partners subsequently sold the business to an insurance company run by the Richardson family, enabling him to concentrate more fully on what by then had become to him the more interesting and more profitable business of fund management.2 By that stage, Templeton’s firm was acting as an investment adviser to five different funds, in addition to its conventional clients, and his fund management subsidiary was briefly listed on the stock market.

We know in broad terms the method that Templeton and his colleagues employed to manage the money of their clients, but we do not have the records that enable us to analyze his performance as an investment counselor in great detail.3 An internal memo prepared by one of Templeton’s colleagues, reproduced in the Appendix, showed that the firm did attempt to measure and report to clients how much value its advice had added. Between 1947 and 1952, the memo suggests that, according to the firm’s “progress index,” a representative client’s portfolio was worth 25 percent more “than it would have probably have been worth if it had not been under continuous supervision” by Templeton and his colleagues. Templeton himself at one point refers to the success of his own personal portfolio and suggests that the impact of portfolio planning could be to double a client’s funds over 20 years. In practice it is not as easy to judge investment performance in an advisory business as it is for a fund, since so much in the former case depends on the individual circumstances and risk profile of the client.4 The performance of a fund, which of necessity and by design maintains a single portfolio for all its investors, is more transparent and therefore easier for an outsider to analyze. Judging by the steady growth of the business, however, there seems no reason to doubt that the results of the firm’s disciplined investment strategy were satisfactory.

In a magazine profile some years after the business was established, Templeton described the role of an investment counsel as follows.

Our role as investment counsel is not unlike that of a doctor or a lawyer—except that there are no midnight emergencies.. . . Much as a law firm has its specialists in various phases of law, we have specialists in the different types of investments: electronics, steel, transport, petroleum, etc. And our clients regard us as they would their doctor or their lawyer, with confidence. We, in turn, respect their confidence and confidences and treat them and their investment needs in an individual manner just as a doctor would treat the needs of those who come to him. The relationship between counselor and client is, and must be, highly personal since each client’s problems differ from those of all others.

What we do know, from the firm’s surviving records, is that John Templeton’s advisory firm managed most clients’ money on the basis of what he said had come to be known as the Yale method, so called after the university that had adopted the approach at the time. As Yale was Templeton’s own alma mater, from which he had graduated in 1934 with a degree in economics, it is interesting to speculate how and when it came to adopt the principles he employed in managing money for his own firm’s clients. Did he himself have a say in the new strategy being adopted by the university, as his letters to clients seem to imply? There is an intriguing suggestion that Yale was one of the few institutions to which John Templeton refused to give any money later in his life, so there may be more to this story than we have been able to establish. (The Yale method described by Templeton should not be confused with the multi-asset strategy adopted more recently by the Yale Endowment Fund, an approach introduced by Yale’s chief investment officer, David Swensen.)

It is probably worth recalling that at the time of his becoming a professional investor, the science of investment was still in its relative infancy. Benjamin Graham’s seminal textbook Security Analysis, for example, written with David Dodd, had only been published for the first time in 1934. (Templeton read and appreciated Graham’s work, describing it later as one of the greatest influences on his thinking.) Another landmark text for security analysts, The Theory of Investment Value, by John Burr Williams, originally written as a thesis at Harvard University, was not published until 1938. By then Templeton had already completed his education in England with two years as a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford University. While in Oxford, although he had majored in economics at Yale, he was taught by a law don at his college, Balliol. Despite its eminence, the University of Oxford employed no specialist tutors in business, let alone finance or investment, at that time.

The essential feature of Templeton’s approach as an investment counselor was to adjust the amount of money that investors held in the three main asset classes—equities, bonds, and cash—in the light of the stock market’s current strength or weakness. When the market was strong, or high compared to its normal trading levels, the proportion in stocks was reduced. When the market was down, and trading at a low level relative to its normal performance, the holdings of equities were increased. Any money that was not invested in equities was held instead in bonds or cash. This broad approach is one that is still followed by investment advisory firms today, although the basis for deciding how much to allocate to each of the main asset classes varies markedly from firm to firm and is rarely as systematic as Templeton’s approach. In the 1940s when Templeton first began to implement such an approach, however, it was still a relative novelty.

The distinctive attribute of the Yale method, which came naturally to Templeton’s orderly mind, was its use of statistical analysis to assess the level of the stock market. He employed a formulaic approach, rather than human judgement, in determining what proportion of clients’ money should be held in equities. This figure was directly and explicitly related to the value of the Dow Jones Industrial Average, the most widely followed index of its day. The normal equity allocation for an average client of the firm was 60 percent, although this proportion could vary from as little as 25 percent to as much 90 percent, depending on an individual’s particular circumstances. This normal equity allocation was then adjusted up or down to reflect the extent to which, in the firm’s judgment, the market had risen above its “normal zone.” So, for the average client, the equity proportion could in theory rise from its baseline of 60 percent to as much as 100 percent, or fall to as little as 0 percent at times of market extremes.

One of the first surviving memos that Templeton wrote to his clients dates from 1945 and makes the case for a disciplined, simple, and coherent approach to investment.

Memorandum to Clients 1945

It is a continual source of surprise to Mr. Vance, Mr. Dobbrow and me, when speaking for the first time with investors with whom we have not spoken before, that so very many people seem never to have thought out comprehensively the nature and problems of investment management. So many go along, year after year, in a haphazard manner, buying a stock now and then whenever some situation, which particularly strikes their fancy, is called to their attention.

In a steady or rising market, the haphazard investor usually obtains profitable results and is lulled into a false sense of security. Then along comes a decline like those which culminated in 1921, 1932, 1938, and 1942 and the good record is more than wiped out, because he had no plan for capturing and locking up the profits in the happy days.

In a rising market, inexperienced investors may obtain the best results, results far surpassing the averages, because they often select highly volatile stocks. As every analyst knows, the fastest rises are to be expected in low priced stocks, stocks of marginal companies, and stocks of companies having large debt and preferred claims. It only takes a few minutes to select a list of stocks which is sure to surpass the market averages, if the average rises. The catch is that, if the market declines, those same stocks are the ones which fall with disastrous acceleration.5

Many people act as if the selection of particular stocks and bonds is about all there is to the problem of conducting an investment program. Of course, the element of “selection” is important. A carefully thought out method for weeding out overvalued stocks and replacing them with undervalued stocks does produce profits. But the backbone of an investment program is the question of “when to buy” and “when to sell.” The first step in planning is to divide the stocks and equities on the one hand from the cash and bonds on the other. The second step is to think out and adhere to a program for shifting out of stocks when they are high and back into stocks when they are again quoted at bargain prices.

The stock market always has been, and always will be, subject to wide degrees of fluctuations. When prices decline farther and farther, it is only natural human emotion to become cautious. Investors who have no prearranged plan to guide them not only fail to add to their stock holdings at the lower levels (sometimes because they have nothing left to buy with), but too frequently they add to the downward pressure by selling out part or all the stocks they own. Conversely, at other times, stock prices are pushed up far above real values by the understandable human tendency to buy when businessmen and friends are preponderantly prosperous and optimistic.

If an investor can sell out when the very top is reached and then buy back at the nadir of the subsequent stock market decline, he will indeed, grow rich quickly. But this can be done only by extraordinary luck. We have never found anyone who could forecast the rises and declines of the stock market correctly and consistently. Mr. Alfred Cowles recently completed a week-by-week study of the results which would have been obtained by following strictly the forecasting advice of eleven agencies which have published stock market trend forecasts throughout the 15 years from 1928 to 1943. He found that the forecasts were correct only 0.2 of 1 percent more than would be expected if the forecasts had been made just at random.

If no one can forecast the stock market trend accurately and consistently, how then, it may be asked, can an investment plan include the important element of shifting the balance between stocks and bonds in the fund? In answer to that question, this company developed in 1938, and put into practice, certain principles which make use of the major market fluctuations without attempting to forecast. Subsequently, such principles have become known as the “Yale Plan” or the “Vassar Plan.” The successful results of these principles in the management of those two college endowments are available in published sources.

In simplest terms, the “balance” of the investment fund is shifted gradually step-by-step away from stocks and into bonds when the stock market rises and then subsequently back from bonds into stocks when the market declines. The result is a moderate growth in the invested funds over each completed market cycle, without the need for any predictions of trends or turning points. An investment plan incorporating these principles assures you that you will be ready and able to buy stocks in periods of gloom when others are selling and that you will be selling when prices are reaching new high levels and optimism abounds.

Any sound long-range investment program requires patience and perseverance. Perhaps that is why so few investors follow any plan. Years may go by before the risks of haphazard stock purchasing are revealed by losses. And years may go by before experience proves the increased safety and enduring growth achieved by planning. Over a period of 20 years, however, it is not too much to expect that investment planning may cause the invested funds to double.6

This message was one that continued to form the basis of the firm’s pitch to clients for many years. By 1957, according to an internal document, Templeton and his colleagues were using this method as the basis of their advice to 99 percent of their clients. He believed that as the manager of “other people’s money,” it was “my duty—an act of faith—to see that their money is handled wisely,”7 a principle to which he held firm throughout his career. High professional standards were not to be compromised. That did not mean, however, that the business was not run in a commercial way. As a businessman, John Templeton was well aware of the commercial value to his firm of having his clients invested in what was, at heart, a standardized form of investment program, one that could be replicated across many portfolios with little increase in cost. His biggest regret, as we have seen, later was that he did not spend more time on marketing the business.

How then did the system work? This is how Templeton himself set out to explain the methodology in the mid 1950s.

What Is Normal for Stock Prices?

Confidential Memorandum to Clients, May 17, 1954

The economic theory developed by Templeton, Dobbrow & Vance, Inc. for calculating the normal level of stock prices is simple. There are only three elements:

1. Stock prices would be normal if they bore the same relationship to current earnings as has been customary in the latest 20 years.

2. Stock prices would be normal if they bore the same relationship to the current cost of replacing the assets of the corporations as has been customary in the latest 20 years.

3. When, because of changes in tax laws or changes in the money supply, high-grade preferred stocks sell lower in relation to dividends than has been customary in the last 20 years, then it should be normal for common stocks to sell lower in relation to earnings; and vice versa.

Although the theory is simple, the actual calculation involves many thousands of figures. We take care to define accurately each word used in the three principles above; and then the arithmetic is worked out on the basis of a large sample of representative stocks.

The estimate of normal based on the three principles above is valid only when applied to a diversified list of industrial common stocks. Different principles are needed if we attempt to appraise the normal for any particular stock. In order that our calculations may be always up-to-date, normal for stock prices is recalculated each month.

In the latest 20 years normal has shown a strong upward tendency, partly because of the change in the purchasing power of the dollar, but more importantly because corporations have retained (after payment of dividends) a large part of their earnings each year.

Normal for stock prices based on the principles expressed above has been computed consistently at a higher figure than the figure arrived at by any other agency attempting to calculate normal. This has meant that the clients of Templeton, Dobbrow & Vance, Inc. have been more heavily invested in common stocks and this has been a profitable situation so far.

It is interesting to note how the three principles mentioned in this memo are all variants of market valuation methods that remain widely adopted today, although better known in some cases by other names. The relationship between the market’s current price-earnings ratio and its long-run average is a calculation that has been popularized recently by Professor Robert Shiller as the “cyclically adjusted price-earnings ratio.”8 The relationship between market valuations and replacement cost of assets anticipates a formula now better known in professional circles as Tobin’s q, named after the Nobel Prize-winning economist James Tobin, who popularized the idea in an important academic paper in the 1950s.9 The relationship between the yield on fixed interest securities and the yield on equities is a widely used analytical tool, one formulation of which is the basis of the so-called Federal Reserve model, so called because of its use in research published by the U.S. central bank in the 1990s.

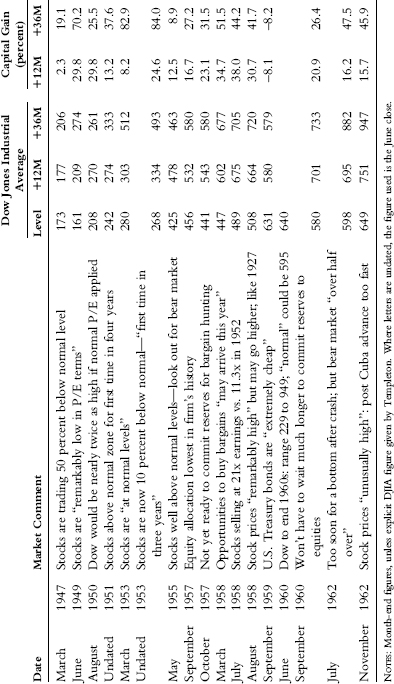

One of Templeton’s colleagues at Templeton, Dobbrow & Vance, Brevoort Stout, added some further explanatory detail of the practical issues involved in running such a program for clients. The table at the end of his memo (reproduced here as Table 2.1) illustrates how simply a client’s stock market exposure would be adjusted for different levels of the stock market, as represented by the Dow Jones Industrial Average. (It was not until the 1970s that the S&P 500 index, rather than the Dow Jones index, was to become the most widely used index in measuring the performance of the market.)

Table 2.1 Sample of Typical 60 Percent Program

Source: John Templeton archive.

| Dow Jones Industrial Average Above 546 | Program Calls for No Stocks | |

| Sixth Zone Above Normal | 496–546 | 10% Maximum in Stocks |

| Fifth Zone Above Normal | 451–496 | 20% Maximum in Stocks |

| Fourth Zone Above Normal | 410–451 | 30% Maximum in Stocks |

| Third Zone Above Normal | 373–410 | 40% Maximum in Stocks |

| Second Zone Above Normal | 339–373 | 50% Maximum in Stocks |

| First Zone Above Normal | 308–339 | 60% Maximum in Stocks |

| Normal Zone | 293–308 | No Change Necessary |

| First Zone Below Normal | 264–293 | 60% Minimum in Stocks |

| Second Zone Below Normal | 238–264 | 70% Minimum in Stocks |

| Third Zone Below Normal | 214–238 | 80% Minimum in Stocks |

| Fourth Zone Below Normal | 193–214 | 90% Minimum in Stocks |

| Below 193 | Fully Invested in Stocks |

Memorandum to Clients October 1, 1953

Those of our clients who follow a long-range investment “program” (and the great majority do) may find it helpful if we review and explain several of the practical considerations which arise when the level of stock prices moves from one “zone” to another. To clarify this discussion a typical “60 Percent Program,” based on “normal” as computed late in September 1953, is attached.

Recently stock prices as a whole (usually referred to as “the market”) have been hovering around the boundary between the First Zone Below Normal and the Second Zone Below Normal. [Authors’ note: The Dow Jones Industrial Average closed at 265.7 on October 1, 1953.10] A dip into the Second Zone Below Normal calls for an increase in the proportion each such portfolio holds in stocks. For most clients the increase is 10 percentage points. For example if a portfolio is managed on the basis of a 60 percent program, a drop by the market into the Second Zone Below Normal would call for raising the percentage in stocks to 70 percent of the total fund; a drop into the Third Zone Below Normal would call for 80 percent in stocks.

When, following such purchases, prices rise, no steps would be taken to reduce the percentage in stocks until the market reached the top of the Normal Zone, at which time profits would be taken to a sufficient extent to restore the normal percentage called for by the program. Using the foregoing example of a 60 percent program, no action would be taken to reduce the proportion in stocks until the market rose above normal, at which time sales would be made to restore the proportions to 60 percent in stocks and 40 percent in reserve.

In the process of acting to keep our clients’ portfolios in proper balance according to their respective individual programs, we are confronted with several practical problems. An explanation of these problems and how we solve them may prove timely and enlightening.

Suppose that today the market dropped from the First Zone Below Normal into the Second Zone Below Normal. Theoretically, this would call for stock purchases by hundreds of our clients. It would, however, be impractical and unwise to place buying orders (or make buying recommendations) for all of our clients on any one day.

In the first place, we could not devote the care and attention to each individual client’s requirements necessary to assure the proper selling and buying selections for his portfolio. In the second place, the sudden impact of heavy mass buying on the stocks selected for purchase would tend to drive up the quotations; and would thus defeat our purpose of buying at bargain prices.

Our solution to this problem is to defer, until the date of the month which corresponds to the particular client’s inventory date, our special “balancing review.” For example, portfolios of clients whose quarterly inventories are dated on, say, the 8th of the month, come up for special balancing review on or about the 8th day of each month. (Each portfolio is, of course, reviewed for other purposes more frequently than once each month, but this special balancing review is a fixed monthly routine.) If, on the “balancing date” for a particular client, balancing action is called for by the level of the stock market and by the client’s program, we immediately undertake, or recommend, appropriate balancing transactions for that client.

This procedure spreads balancing transactions for our clientele over the course of 30 days (or more if the market remains only briefly in the zone which requires positive action), permitting careful attention to each client’s needs and avoiding sudden excessive market pressures. It is unlikely that any resulting delay in buying, pending the “balancing review date” would prove disadvantageous. Only in the event that the market drops into a buying zone, recovers from it before the “balancing review date,” and continues to rise to above-normal levels without again returning to or below the buying zone, would the delay cause a client to lose out on profiting fully from such a market price swing.

An additional problem is the proper action in a case such as this: On the client’s balancing review date the market is in a buying zone; we recommend specific purchases; by the time we receive the client’s approval the market is no longer in the buying zone; what then? Unless the intervening rise in the market has been extreme we go ahead with the actual buying once it has been recommended, except that we may have to substitute a different stock for one which has scored too great an individual rise.

Our reasoning is that the exact zone limits are useful tools for program planning purposes but should not be so strictly adhered to as to cause undue hesitation or vacillation in actual practice. It might be pointed out that we recompute the level of the Normal Zone each month. Any resulting change in the Normal Zone causes similar changes in the boundaries between the zones above and below normal. As in the case of the above-mentioned possibility of intervening changes in the level of the stock market, any such intervening changes in our computational normal are not allowed to prevent prompt and logical action.

To summarize; in the case of those portfolios for which we are authorized to act on our own discretion we reach our balancing decision on the basis of the relation of the market to the program on balancing date and, if action is required, we place orders at once. For those clients to whom we offer recommendations, we recommend on the basis of the relation of the market to the program on balancing date, and execute when approval has been received regardless of intervening market movements unless such movements have been extreme. Those few clients who, on receipt of our recommendations, carry out their own executions, should follow a similar procedure.

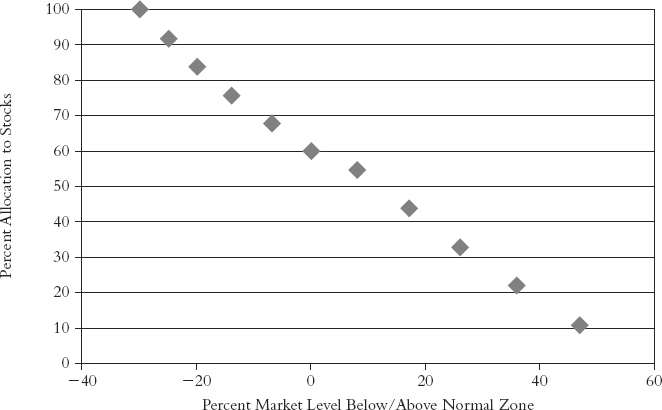

From this and other memoranda prepared by the firm, it is possible to deduce more precisely how the allocation to equities varied with the level of the Dow Jones Industrial Average and its relationship to its “normal” range, as calculated by Templeton and his colleagues. (See Table 2.1.) If and when the stock market was trading more than 60 percent above its “normal” level, the proportion in stocks should be reduced to zero. When stocks were trading more than 30 percent below normal, the allocation to stocks for the average client could theoretically rise to as much as 100 percent. (See Figure 2.1.)

The first point to note here are that the allocation to equities which Templeton and his colleagues were recommending—both the 60 percent starting point for the average client and the potential maximum allocation—was higher than many of his peers would have been comfortable with at the time. As Templeton himself acknowledged in the memo cited earlier, this was one of the reasons why his clients enjoyed higher returns than those who retained other advisers. At the same time the method was, evidently, a contrarian strategy—buy when others are selling, and sell when others are buying. This same approach was to become the hallmark of his later career as a fund manager and remained an essential feature of his investment approach throughout his life. Nobody with any experience of managing client money however should underestimate the difficulty of persuading clients to increase their holdings of stocks when markets have been falling or selling down their holdings when it has been rising.

In fact, most of the strands that were later to be formulated as John Templeton’s investment approach in his later years are already clearly evident in his writings during his years as an investment counsel. A number of themes, which recur throughout the firm’s communications with its clients, anticipate the ideas with which he was later to be closely associated as a prominent and public figure in the investment business. The bedrock of his philosophy of investment, it is clear, was already formed before he was 30 and was not to alter in any material way subsequently. Experience only served to reinforce the strength of these convictions.

At different times John Templeton would offer clients the firm’s analysis of where the stock market stood in relation to the normal values it calculated on a monthly basis. One of the first occasions we can find was a memo written in March 1947, entitled The Future Range of Stock Prices. In this he explained at some length, based on analyzing three familiar factors—corporate earnings, bond yields and the replacement cost of assets—why in the firm’s view the stock market was currently trading some 50 percent below what could be described as its “normal zone.” Several other examples are given in the Appendix.

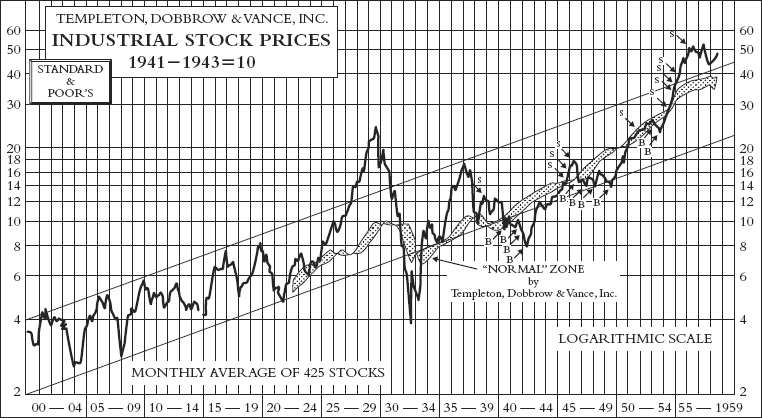

A simpler way to grasp how that the system worked can be seen in Figure 2.2, one of a number of attempts made by the firm to illustrate how the methodology worked. The shaded area in the middle of the two upwardly sloping trend lines shows the firm’s estimates of what would be a normal trading range for the stock market, based on their calculations of historical experience. This can be then compared with the actual behavior of the market, represented in this case by the Standard & Poor’s index of industrial stock prices, rather than the Dow Jones index. Although the firm did not start advising clients until World War II, the calculations are shown back to the early 1920s. This has the happy effect of showing that the methodology would have reduced client holdings of stocks in the run up to the 1929 crash, when the “normal” zone was well below the actual market level, and again in the late 1930s. The letters B and S show the points at which the firm would have advised an increase or reduction in their clients’ holdings of equities, based on these calculations. It shows the firm advising clients to build their equity exposure during most of the war years and again in the late 1940s and early 1950s, but reducing it in 1946–1947 and again in the mid-1950s.

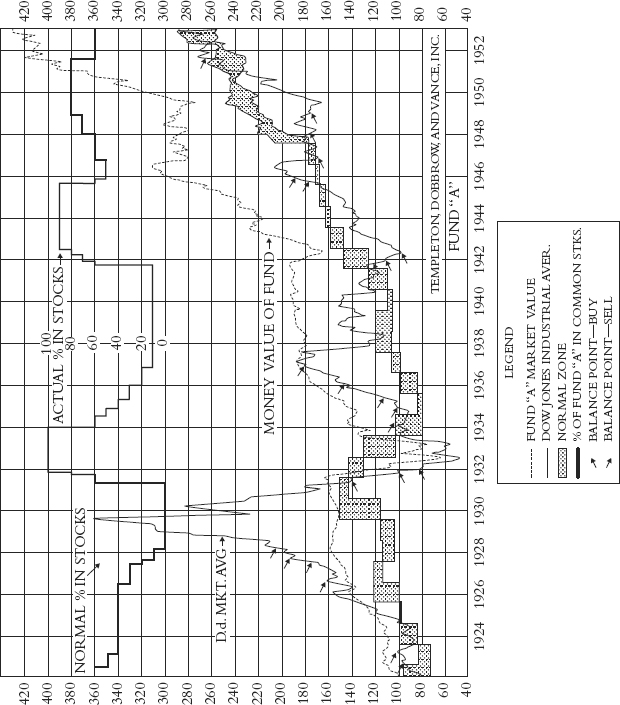

A second chart sent some years earlier to the firm’s clients, but less easy to interpret, is even more explicit about how the firm’s methodology would have positioned their client’s equity allocation in the years 1922 to 1953. The key part of the chart is reproduced in Figure 2.3. It shows the equity allocation of a notional average client fund being cut from 60 percent in 1922 to 0 percent in early 1928, then increasing all the way back up to 100 percent by the end of 1931.

Table 2.2 summarizes a number of the comments from the firm’s papers that Templeton kept in his files. It allows us to see how these judgments compared to the subsequent behavior of the market. It is important to emphasize that the purpose of the Yale method was to take subjective analysis out of the process. Templeton and his colleagues always emphasized that short-term movements were unpredictable. The primary purpose of estimating the Normal Zone was to provide an “indicator of risk,” not to attempt to predict what future returns might be. The analysis did however enable Templeton to describe, in his 1947 memo, a possible range of future levels for the Dow Jones Industrial Average.

Table 2.2 Dow Jones Industrial Averages/Capital Gain

Source: John Templeton archive, Independent Investor.

Over the subsequent 10 years, he suggested, it was likely that the Dow, then standing at 173, would trade in a range between 176 and 256 roughly 50 percent of the time, below 173 around 25 percent of the time, and above 256 25 percent of the time. With the full benefit of hindsight we can see that in fact he underestimated the strength of the postwar bull market that was about to unfold—ironically, perhaps, vindication of his view that it is impossible to forecast market levels reliably in advance. In the 10 years that followed his memo, the Dow Jones traded below 173 just 2 percent of the time; in the 176–256 range 39 percent of the time; and in the highest range (above 256) 59 percent of the time. The risk, as it turned out, was all on the upside.

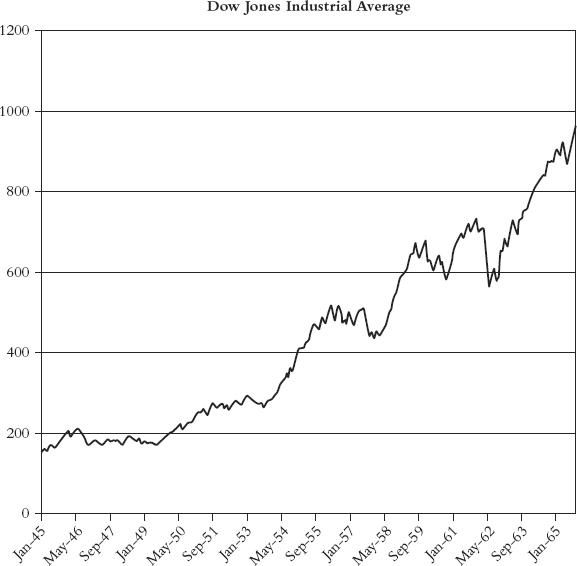

The table listing some of the comments on the level of the market that were made by the firm between 1947 and 1960 is worth analyzing. Diligent readers can work out for themselves how these comments related to the level of the market at the time by observing the chart of the performance of the Dow Jones Industrial Average over the same period. In general the method seems to have served its purpose in reducing clients’ exposure to volatility. As we now know, the period 1945 to 1960 was one of continued economic growth and prosperity, punctuated by intermittent military concerns (and one war, in Korea 1950–1951). There was, unusually, only one severe recession, in 1957, for which clients of Templeton, Dobbrow & Vance were well prepared, having been urged to start reducing their holdings of equities as early as the spring of 1955. True to its normal form, the stock market itself turned down in mid-1956, some months before the onset of the recession. Note also, however, how in almost every case the stock market was higher 12 and 36 months after Templeton’s comments were published—a useful reminder that in normal times investors neglect equities at their peril.

There is no better way of capturing the way that the firm’s methods worked than by comparing side by side, as Templeton himself did in 1955, his comments on where the stock market stood in 1950 and his observations on the same subject five years later (see Appendix for reproduced memo). Clear thinking, augmented by numerically quantified statistics, was what he had promised his clients; and that in general, as the evidence of The Templeton Letter, as his notes to clients were called, makes clear, was what they received. It was simply a function of historical experience that his historical studies, relating as they did to experience in the first half of the century, led him to underestimate the length of the 1949–1956 bull market. The second half of the twentieth century turned out to be very different in character to the first. See Figure 2.4.

For the modern investor, it is interesting to note too how Templeton succeeded in picking up on some longer-term themes that were to become of greater importance to investors as the century progressed. In 1945, for example, he wrote a long article for Barron’s explaining why he was expecting a higher price for oil and greatly increased earnings for oil producing companies. His clients, he noted in an update 11 years later, had been more invested in oil stocks than any other single industry. The six stocks he named in the original Barron’s article had risen 620 percent over the 11-year period. By the end of the 1950s, in his view, the risks in owning oil stocks had increased dramatically however. Around the same time, he tackled the fashionable argument on Wall Street, widely used to justify the new highs that the stock market was making, that the onset of inflation in the postwar period, which he had long forecast, justified the high level of stock prices prevailing at that time. (It did not, in his view, but events were to demonstrate that the stock market continued to power ahead well into the 1960s.)

At periodic intervals, Templeton wrote letters to his clients explaining why a sudden fall in the stock market was actually good—not bad—news for investors with a medium to long-term horizon. The idea that stocks can be more, not less, attractive when the market falls is one of the counterintuitive insights that inexperienced investors sometimes find difficult to take on board.11 Graham and Buffett are among those who have tried to explain this apparent paradox. It is hard though to match the clarity and lucidity of Templeton’s explanation, written at a time, shortly after World War II, when the markets were becoming preoccupied by the developing Cold War, and many stocks were selling on single figure P/E ratios. (By this point in 1948, it is worth noting, clients of the firm had been allocated above normal weightings in equities for nearly three years, and as the market had traded sideways for almost the entire period, it is possible to speculate that some were anxiously demanding reassurance that their portfolios were still in capable hands.)

The Best Thing That Could Happen

Memorandum to Clients September 21, 1948

The stock market went down yesterday. My friends in Wall Street are sad. I can understand their emotions; but it only illustrates again the fact that more and more investors should adopt and adhere to the long-range non-forecasting programs used by the clients of Templeton, Dobbrow & Vance, Inc. These programs are designed to profit from stock market cycles without the need for predicting such cycles.

For an investor following a program of this nature, as we have said before, the best thing which could happen is to have the stock market go down from today’s level of 177 to 128 before the next long bull market begins. An investor following an “average program” has 70 percent in common stocks today which will participate in the capital gains during the next bull market. However, if the market declines to 128 before the bull market begins, such an investor will have 100 percent in stocks with which to participate in future capital gains.

In other words, if a bull market begins now the investor will make a large profit; but if the market first declines to 128 before the bull market begins he will make an extra $19,000 approximately on each $100,000 involved in the program.12

If the market continues to decline, the long-range programs will call for purchasing more stocks at successively low levels. Of course, if there were any way to know for sure that the stock market would decline to 128 we would wait until then to make any purchases. In fact, we would go further than that and sell out the stocks now held in order to repurchase at the bottom.

But the fact is that no one can possibly know for sure what the stock market will do. It is also possible that a long bull market may start immediately.13 If there were any way to know this for certain, we should immediately buy common stocks on margin at once. Here again, no one can possible by sure what the stock market will do. The prudent and conservative policy is to follow a long-range program designed to profit from stock market cycles without the need for predicting either the timing or extent of such cycles.

Because the stock market declined yesterday and is now 9 percent below its level three months ago, investors generally are unhappy. Even for those investors who have not yet adopted a long-range program this emotion is illogical, if such investors are still in the stage of accumulating their wealth. Low market prices work to the advantage of an investor who makes it a practice to reinvest dividends or an investor who makes annual savings from his business or salary.

For more than two years stock prices have been remarkably low in relation to earnings. In fact, today stock prices are lower in relation to earnings than in any peacetime year as far back as records are available. This means simply that a person with new money to invest can obtain unusual bargains. [Authors’ Note: The Dow Jones Industrial Average in September 1948 traded in a narrow range between 178 and 185 and was not to start rising until June 1949, after which it rose by around 40 percent in the next two years.]

He can buy shares in some of America’s largest and soundest enterprises for less than five times current rate of earnings. If the current rate of earnings is maintained, the net worth of his shares plus the dividends received will cause the value of his investment to double in less than five years. Even if future earnings were only one-half of current earnings, his purchases would still represent attractive bargains.

This memorandum is not written merely to point out the silver lining of a cloud. It is intended as a part of the long educational program to persuade more and more investors to adopt sound and long-range investment programs.

In December 1950 Templeton addressed the question of how to pick the best stocks within a portfolio. This is a simple and cogent outline of the methods that he was to refine and develop over the rest of his career as a professional investor. As it grew, his investment counseling firm was to devote increasing amounts of time and effort to analyzing and selecting individual stocks. Note in particular the emphasis on looking at both value and growth criteria, and the idea that the most successful investments are likely to be those that are unpopular at the time they are purchased. Yet, even at this early stage in his career, it was evident that his investment style could not be classified as either a simplistic “value” or “growth” approach. He was clear, for example, that stocks with very high dividend yields, one measure favored by value investors, were less likely to produce good results than lower yielding stocks with superior growth prospects. It is probably worth remembering that at the time the terms “value” and “growth” did not carry the same connotations as they do know. For Templeton it was quite likely that he describe a stock as “value” because he was underpaying for its “growth.” In recent years there has been an obsession with “style” which seeks to categorize investors according to the types of stocks in which they seem to invest. This is the antithesis of the approach suggested by Templeton.

Letter to Clients December 1950

After an investor has decided the percentage of total funds which he should keep in common stocks, then he faces the problem of selecting the best stocks. The investor does not wish to purchase a list of stocks selected at random, but rather he wishes to purchase only those stocks which are the best.

Some people, especially institutional investors and trustees, use the words “best stocks” to mean stocks of “high investment quality.” Stocks of high investment quality are those having a tendency to rise very little in favorable markets and to decline very little in unfavorable markets. These are usually stocks of large and famous corporations, having a long record of steady dividends. It is a simple matter for an experience investor to make a list of those stocks having high investment quality. There is little disagreement among security analysts in determining which stocks deserve this rating.

Other people use the words “best stocks” to mean stocks having “a good short-term outlook.” In fact, this is the viewpoint most frequently used in selecting stocks. A stock may be selected because the company is expected to pay an extra dividend, because the company is expected to have an increase in sales volume next year, or because of a rumor that the stock may be split. This tendency to emphasize the temporary outlook is the cause for the wide fluctuation in price which most stocks undergo every year.

Now when we use the words “best stocks,” we mean simply the best values—that is to say, those stocks whose market prices are lowest in relation to their intrinsic value. The question of investment quality and the question of short-term outlook are only two among the multitude of factors which must be computed and combined in the complex task of estimating the intrinsic value. For each stock we arrive at a specific estimate of intrinsic value. These estimates are kept up-to-date by frequent review. Each month the market price for each stock is compared with the estimated intrinsic value of that stock.

When the market price for a particular stock rises above intrinsic value to an unreasonable extent, we notify clients holding that stock and suggest that the stock should be sold. Conversely, when the market price falls below the intrinsic value for a particular stock to an unreasonable extent, we put that stock on a list of “stocks which can be recommended to clients for purchase.”

To appraise the value of a stock the analyst must consider not just one or two but all factors. Some of these factors are management ability, growth trend, government control, assets per share, average past market prices for the shares, dividends, current earnings, average earnings in previous years, estimates of future earnings, etc.

The appraisal of value is complex and subject to numerous uncertainties. It should not be expected that all selections made on this basis, or any other basis, can prove successful. But although the “intrinsic value” is only an estimate, the person or company whose studies are crystalized logically, systematically and consistently into a specific estimate has an advantage over other stock purchasers and sellers whose ideas are often nebulous and incomplete. A comprehensive and systematic analysis reduces the human tendency to overemphasize one or two dramatic factors and overlook others.

The investor who purchases a stock because of basic value can enjoy a certain peace of mind. If after purchasing a stock at a low price in relation to value, the price continues to decline, then it is simply a better bargain than it was before. On the other hand, the speculator who purchases in the hope of a quick profit places himself at the mercy of market fluctuations, because he can succeed only by selling his shares to other speculators at higher prices.

The investor who selects stocks on the basis of long-term intrinsic value must expect certain problems. In the first place, he should expect usually to purchase stocks which are thoroughly unpopular. Only when a stock is unpopular is the price likely to be depressed greatly below intrinsic value. It is not easy to act contrary to popular opinion. When the price of a stock is very low, there are usually obvious reasons which have caused others to sell the shares and thereby depress the price.

For example, after the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor the outlook for the automobile industry was recognized as unfavorable. It was widely predicted that the manufacture of automobiles might be stopped completely. Shares of General Motors sold as low as 28⅝. The manufacture of automobiles was in fact stopped completely a few months later and not resumed for several years. However, the bargain hunters, who were willing to act against public opinion and purchase General Motors below 30 after Pearl Harbor, were well rewarded because the shares were later split 2-for-1 and are now selling at 47.

In the second place, the investor who selects stocks on the basis of long-term intrinsic value should not expect that the stocks selected will immediately begin to show a profit. If the intrinsic value of a stock is estimated at $40 and then over a period of years unfavorable news depresses the price to $20, the investor may begin to buy this stock because it appears to be one of the best bargains in the market. However, it would be an unusual coincidence if he should happen to make the purchase just at the time when the downward trend is reversed. Ordinarily the downward trend persists for at least a few weeks and sometimes much longer. The investor may hold the shares for a long time before others begin to recognize the intrinsic value.

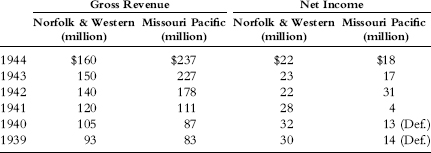

Usually a stock selected for purchase because its market price is very low in relation to intrinsic value sooner or later attracts public favor so that the market price rises above intrinsic value. Even if the stock does not become popular, however, the investment may prove lucrative in the long run. For example, if you can purchase at $20 a stock having $20 a share in assets, earning 20 percent annually on assets and paying out half of earnings, then simply by holding this stock for five years you will receive more than $10 in dividends and more than $10 in the form of increased assets per share. In other words, you may obtain even 100 percent profit on the investment even though the stock continues to be unpopular and sells equally low in relation to earnings, dividends and asset values. Whenever you can buy a large amount of future earning power for a low price, you have made a good investment. [See Table 2.3.]

Table 2.3 Gross Revenue/Net Income

Source: John Templeton archive.

In 1954 Templeton wrote a letter to his clients expanding on his view that the worst way for any medium- to long-term investor to generate income from his investments was to buy the highest yielding shares in the market. He made the case for buying growth stocks instead, underlining the handsome results that could be obtained by buying and holding stocks with the greatest potential for dividend growth. This is further evidence of how, although he is known as a value investor, Templeton’s methods were more subtle, and less easily classified, than that description implies. The notion of “intrinsic value” comes straight out of Ben Graham’s Security Analysis. Yet John Templeton was never a simple follower of the deep value, backward-looking methods made famous by Ben Graham.14 From an early point in his career he was looking for the stocks that were going to produce the greatest total return over a period of years. Implicit in this approach was the need for investors to be patient and wait for the returns to come through.

How to Increase Your Income from Investments

Memorandum to Clients February 15, 1954

Any good investment research man can prepare for you within a few minutes a well-diversified list of stocks yielding over 10 percent. On the basis of market prices on February 10th and the dividends paid in the last 12 months, Van Norman Company yields 10.5 percent, Moore-McCormack Lines 11 percent, Barker Brothers 11.7 percent, Pond Creek Pocahontas 11.9 percent, Butte Copper 12.3 percent, Nash-Kelvinator 12.8 percent, Pacific Tin 13.0 percent, Great Northern Iron Ore 13.0 percent, Inspiration Consolidated Copper 13.1 percent, and Roan Antelope Mines 15.6 percent. These are all well established corporations with shares listed on the New York Stock Exchange.

This is an easy method for increasing your income from investments; but it is the worst of all methods. Stocks sell at low prices in relation to current dividends usually because there are good reasons for expecting that the dividend may be reduced. Investors selecting stocks with high current yield face not only the risk of reduced dividends but also the greater risk of capital losses.

A far wiser method for increasing your income is to select stocks with the highest earnings in relation to market price. This will usually mean that your stocks have good prospects for paying increased dividends rather than prospects for paying reduced dividends. Many good stocks can now be found whose annual earnings are more than 15 percent of the market price.

Such earnings are partly reinvested by the company for the benefit of stockholders which, in turn, leads to still higher earnings per share in future years. Of course, in seeking such stocks you should skip those whose earnings are high for one or two years for abnormal reasons and search rather for those likely to have a high level of earnings for many years in the future.

In the endeavor to increase your income, it is wise also to select growth stocks. Growth stocks are most likely to earn more and pay increased dividends in future years. Usually growth companies have a high rate of earnings in relation to net worth. By retaining a large share of its earnings each year a growth company may be able to double its net assets per share within a relatively few years; and this in turn may lead to increased earnings and dividends.

Another sound method, with which our clients are thoroughly familiar, is to reduce the percentage held in common stocks when the stock market rises far above normal and then in turn to increase the percentage in common stocks when the stock market declines far below normal. At first thought it may seem strange to speak of increasing your income by taking part of your money out of common stocks (when stock prices are high) in order to create a reserve of top-grade bond which usually have low yields.

However, the importance of having a reserve and the use of such reserve to achieve an increase in income will become apparent the next time common stock prices are really low. Then the reserve can be used to purchase more common stocks at prices that are really low in relation to probable earnings and dividends of future years.

For example, let us assume that the stock of X company is paying, and will continue to pay, $1.50 annually in dividends. It may be possible at some time to sell such stock at $30, hold the proceeds temporarily in 3 percent bonds, and then within a few years use this reserve to repurchase at $20, three shares of the same stock for each two shares previously held. This method accomplishes no temporary increase in income with accompanying risk, but rather a solid and permanent increase of income in the long run.

For the purpose of increasing your income, constant watchfulness is also important. Prices of common stocks fluctuate very widely. It is often possible to sell a stock whose price is too high in relation to value and use the proceeds for the purchase at the same time of another stock whose price is too low in relation to its value. Transactions which increase the intrinsic value of your list of investments usually lead to increases in income in the long run.

The Templeton, Dobbrow & Vance Model Fund which started September 30, 1943 can serve as an example of the increased income resulting from the methods mentioned briefly in the four preceding paragraphs. This fund started with a capital of exactly $100,000; and although it is only 68 percent invested in common stocks, it is now earning income at the rate of $11,213 annually, or 11.2 percent of cost. As one more example, consider the case of Mr. M. whose fund of $276,000 was first placed under our investment counsel management exactly 15 years ago. Although this fund is now only 57 percent invested in common stocks, the income is $30,780 annually, which is 10.9 percent of cost.

By using the methods mentioned above, you may increase your income on a sound and permanent basis. Also, these methods should increase both the safety and the capital growth of your investments.

As noted earlier, it should never be forgotten that John Templeton was not just a successful investor, but a shrewd businessman who it is clear was always alert to ways of maximizing the value of his investment counseling business. The following memo that he wrote to his colleagues contains some important advice on the subject of “how to keep clients happy.” To modern eyes the word “indoctrination” may carry connotations that were almost certainly not intended at the time. “Securing customer loyalty” would, we suspect, be a less pejorative phrase to describe the firm’s sensible business objective of retaining the goodwill and custom of its clients!

Memo to Liddell, Scott, Heavner, Palmer, Warner, Andrews

Dated December 1953

Alan has suggested that it might be helpful to all of us if I would try to put down on paper the thoughts which I have developed in the last 12 years on the subject of how to keep a client happy. Actually, my knowledge on this subject is inadequate; and I think that many of you have more aptitude than I. It is a difficult subject because it seems to me that the influences on the psychological attitudes, decisions and beliefs of human beings are 90 percent subconscious and only 10 percent logical. However, any personal service firm must devote much effort and thought toward continual indoctrination and selling of the clients; and therefore, I will set down below a sort of checklist which may be especially helpful in the work of indoctrinating new clients and others.

1. Most important of all, the investor wants to feel that his list of stocks is the best which could possibly be selected. If he is thoroughly convinced on this score, price fluctuations will appear to be opportunities rather than causes for concern. The best means is to have a long personal talk with a client about each of his stocks at least twice a year. If you explain in great detail why each stock is good and what methods we use in selecting stocks, a client will be happy with his list and will probably be impressed with your wide knowledge. Clients like to know that each of their stocks is subject to continuous restudy and follow-up.

2. The investor will be comfortable if he knows that he is following a sensible program. In each interview and often by letter it is often wise to describe the program he is following. He wants to feel that his program has been carefully prepared with regard to his own particular needs, and that improvements are made frequently. He should understand the reasons why his program is likely to prove not only safer but also more profitable in the long run than any other possible program. Clients usually like to know how many institutions use this non-forecasting method. Some counselors make a special point of the various ways in which they have diversified the client’s holdings.

3. The investor wants to feel that his affairs are managed by a group of wise and prudent men. No one of us would want to say this about ourselves. However, each of us should seek opportunities to describe to the client the background and wisdom and success of each other man in the organization. Some counselors make a specially strong point of the fact that other sources of advice may be biased, whereas investment counsel works in the client’s interest only.

4. It is human to be subconsciously influenced by appearances. Those banks which inhabit marble palaces usually attract the most customers. This means not only appearances of officers but also size of organization, age, clothing, automobiles, stationery, telephone handling, booklets, and many other things. The feeling of optimism and prosperity is contagious. The counselor whose manner and words reflect uncertainty or disappointment will quickly give the same feeling to the client; and the counselor whose manner and words reflect confidence and prosperity will quickly give the feeling of confidence to the client.

5. The majority of clients are interested in safety of income and growth of income more than anything else. We should make this a major point in talks with clients and in letters. For example, we should show a client not only the income percentage based on current market prices but also the percentage based on capital originally listed with us.

6. Clients are also interested in capital gains, some more and some less. Trust companies and most large investment counsel ignore this subject completely; but in my opinion we should not overlook an opportunity to point out a good capital gains record. From experience, it appears that the client is most influenced if his record is compared with that of some other investor or firm of high reputation. There is a wide variety of methods for comparing capital changes, some of which were listed in the memo I wrote a couple of years ago concerning the results letters.

7. Each of us should keep in mind the strong psychological effect of repetition. Pointing out a good record once does not have nearly the effect of pointing out the same record four or five times. Contacts with clients week after week which report mostly items of important news about their stocks have accumulative subconscious favorable effect, whereas a series of letters or contacts which mention problems have the opposite effect. Because of repetition the question of having investment counsel costs paid by the custodian has utmost importance. Trust company costs are seldom mentioned by beneficiaries because they never see the bills or make out the checks. However, although no client minds paying the first bill, he does build up a subconscious sensitivity by having to make out a check every three months for an amount which is usually one of his largest expenses.

8. Intimate knowledge of every detail of family affairs is a proper expectation of the client, because investment counsel does fit selections to the needs and wishes of the particular client. If the counselor remembers most of the details about the family, taxes and investment holdings of the client, this gives the client a feeling that he is getting close personal attention. Estate planning is a helpful thing in establishing this close relationship. Personal friendship should be cultivated in various ways because this subconsciously encourages a favorable attitude toward each question that may arise.

9. To some extent, clients are happy to learn how good our record has been for other clients. The Model Fund is a help in this respect and should often be shown to the clients and the method of comparison described in some detail. Testimonial letters are helpful also.

10. Frequent mailing of reports and studies gives the client a better understanding of our work. This helps the client to learn how much research and thoughtful work in many fields is devoted to his financial welfare. This sort of memo is especially helpful to keep in touch with prospective clients.

11. We should explain much more often than we do just how much more the client owns in terms of earning power per dollar invested and real value per dollar invested than he had when he came with us. When recommending switching from one stock to another we should often give a tabulation of five or six reasons with figures showing just how the stock purchased is better than the stock sold.

Reading through the letters to clients shows, as you would expect, that the markets were not the only concern of the firm. The principals also tackled more mundane issues such as tax and legacies. They became early advocates of profit-sharing plans for employees. For all his success in building a profitable investment counsel firm, and taking a prominent role in the campaign to raise awareness of the new profession, it is clear that by the end of the 1950s John Templeton was beginning to think of his next move. His experience in setting up and advising investment funds, which had begun some eight years earlier, coupled with his awareness that the world was undergoing far-reaching changes, creating new opportunities for investors, was to persuade him that the time had come to sell his advisory business and concentrate his efforts on the attractive and fast growing business of fund management.

Looking back later, Templeton regrets that he took so long to realize the value of going into mutual funds. “I was much too late into it” he said in an interview with the authors in 2003. “If I had been wise, I would have started much sooner, but I noticed that the people who had started mutual funds were getting more clients and more money than I was. At that time, there were tax advantages in having a fund incorporated in Canada, so I formed the Templeton Growth Fund of Canada. It was available to Americans as well as Canadians. However it was 1954 before I had any fun, and even then, I didn’t have salesmen. That was my major mistake.” Quite what a costly mistake that proved to be and it is addressed in the next chapter, which looks at his record as a fund manager.

Notes

1. This was one of the rare occasions when Templeton is known to have used borrowed money to advance his career. He borrowed $10,000 from his former boss at a stockbroking firm to help fund a $40,000 bet that the onset of war would boost the stock market value of many depressed U.S. companies.

2. Later in his career, as the Templeton organization grew much larger on the back of the success of his funds operation, it returned to the investment advisory business, managing segregated accounts for high net worth individuals, those with $1 million or more in personal wealth. By this stage, however, Templeton himself was no longer directly involved in managing private client money.

3. From time to time in his memos Templeton refers to the performance of one or two individual clients, and the firm also ran a model fund for some of this period, but we have not been able to locate a comprehensive record of client returns.

4. One reason why fund management is so much more profitable a business is that a fund manager is free to concentrate on running a single portfolio without the need to spend time creating individual portfolios to match the specific needs of clients.

5. The sensitivity of individual stocks to movements in the stock market averages is known in modern financial theory as beta. A stock with a beta of 0.5 is one that rises 5 percent when the market is up 10 percent, and falls by 5 percent when it is down by 10 percent. A stock with a beta of 1.5 is one that rises or falls by 15 percent for an equivalent 10 percent move in the stock market averages. The problem with betas is that they are based on historical performance and tend not to remain constant over time.

6. This is an interesting observation. Presumably he means that invested funds would be double what they would otherwise have been. For funds to double over 20 years implies a compound rate of growth of 3.5 percent per annum.

7. John Marks Templeton, The Templeton Plan: 21 Steps To Personal Success and Real Happiness (Philadelphia and London: Templeton Press, 1987), 72, as told to James Ellison.

8. See Professor Shiller’s website for more information.

9. This concept has been highlighted by the British economist Andrew Smithers in his books Valuing Wall Street (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2000) and Wall Street Revalued (Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, 2009).

10. The Dow Jones Industrial Average closed on October 1, 1953, when this memo was written, at 265.7. It could therefore be described as being in the First Zone Below Normal, implying a slight increase in the holding of equities.

11. It is fair to make the point that the opportunities to invest cheaply when the market falls most benefits investors who still have many years of investing ahead of them. For a retiree in the distribution stage of his investment life cycle, the advantages are less clear-cut.

12. In fact, the stock market, as measured by the Dow Jones Industrial Average, was to fall to a low of 163.8 in mid-June 1949, so was already close to its cyclical low.

13. A long bull market was indeed set to start the following year and was to take the Dow Jones Industrial Average up to 560 at its next peak in 1956, or roughly three times the level at which it was trading at the time this memo was written.

14. “Ben was a very wise man. He had a splendid method. But if he were alive today he would be doing something else, relying on newer and more varied concepts.” Barryessa and Kirzner, Global Investing, 134.