Chapter 4

Philosophy in Action

The philosophy that Sir John Templeton developed and refined over the course of his long investment career was faithfully reflected in the way that he managed money—both his own and that of others, whether they were clients of his investment counsel firm or investors in his funds. The essence of that approach was: to act on logic rather than emotion; to rely on quantitative rather than subjective analysis; to think for himself and ignore what other investors were saying and doing; and to approach the business of investment in a systematic way that reflected his own deep understanding of how the financial markets actually work. His greatest advantage as a professional investor was that his investment philosophy was both thorough and consistent, and entirely attuned to his own knowledge, personality, and temperament. The qualities that any investor with an investment philosophy such as Templeton’s requires the ability to be patient, calm, dispassionate, bold—were all ones that he possessed to a marked degree. “Sir John,” says fund manager Ken Fisher, “had ice in his veins and really lived the idea: Don’t follow the herd.”

To help popularize his approach, throughout his life John Templeton sought to capture the essence of his approach in a series of maxims about the requirements for investment success. Phrases such as “The best time to invest is at the point of maximum pessimism” and “This time it’s different—the four most dangerous words in investment” have passed into common usage in the profession. In this chapter we use these maxims as a framework for discussing how his philosophy can be implemented in practice—recognizing at the outset that this is no easy task, and that there are important differences in their relevance to private and institutional investors, just as the way in which Templeton advised clients to invest was different in some ways than the way he managed a fund.

The version of the maxims we have chosen to use is the one that was published in World Monitor: The Christian Science Monitor Monthly in February 1993 under the title “16 Rules for Investment Success.” There are several other versions in existence, however, some with a different number of rules, or differences in wording. The version shown here can be usefully compared to the version published in the first full-length biography of John Templeton. These maxims are reproduced in the Appendix. Between them, these two lists capture all the most important elements of his investment philosophy. For the sake of convenience we refer to the first list as his rules, and the second as his maxims.

It is worth emphasizing at the outset, however, that there is an interesting, and rarely appreciated, paradox in the way that John Templeton approached the business of investment. The paradox is that while the process he adopted was austere in its rigor, and firmly quantitative in its application, his philosophy was rooted less in dry analytical analysis of what works in financial markets than in his understanding of human psychology and behavior. The latter, he believed, was the primary factor that underpins the behavior of security prices and created the bargains for which he spent his life looking. His insights into the human condition were not just central to his moral and religious beliefs, but help to explain why he was always so extraordinarily confident that his methods were the right ones and would, if properly applied, result in superior, lower risk investment performance.

Sir John’s religious and ethical beliefs cannot therefore be seen in isolation from his career as an investor. The reality is that he did not have two sets of fundamental principles—one for life and one for investment. One set of principles underpinned everything that he did. In an important speech, entitled “The Religious Foundation of Liberty and Enterprise,” which he gave at Buena Vista in 1993, shortly after he had sold his fund management business, he outlined what those principles were. Although the focus of this book is primarily on his investment philosophy, the speech is an important source for those seeking to understand the roots of his market philosophy.

The speech lists what he described as the main virtues and vices to which humankind is prone. From these he derived a number of timeless practical issues that are relevant to any investor in any period. The vice of envy, for example, which he defined as joy at the suffering or misfortune of others, is often reflected in society by penal tax rates and the expropriation of private property. One of the rules by which Templeton lived was to avoid investing in countries where governments either imposed high tax rates or failed to respect private property rights. The latter can be reflected in outright expropriation, or in less obvious ways, such as a failure to enforce copyright protection and intellectual property rights.

Similarly, because of greed, another widespread vice, “the modern form of capitalism,” Templeton noted, “is often too hedonistic and unethical, and too far removed from traditional virtues. This economic vice is a source of many crimes, public and private. It can also turn up in bad personal habits, like accumulating too much debt or going on buying sprees to improve self-image.” After a decade that saw the collapse through fraud of Enron and Global Crossing, and a full-blown banking crisis induced by banking behavior that was shamefully driven by financial self-interest, the relevance of this observation need hardly be doubted. The abuse of stock options, introduced originally in an effort to align the interests of shareholders and management, but which have since been gradually transformed into a mechanism by which senior managements could enrich themselves at shareholders’ expense with minimal risk, is another prime modern example.

After listing examples of pride and intolerance, Templeton also focused on the flaws in moral relativism, the notion that there are no absolute rights and wrongs, only degrees of wrongdoing. In his view economic utilitarianism, a doctrine to which many elected politicians are vulnerable, is “a version of moral relativism, because it pretends that profit and loss can substitute for right and wrong.” This view was behind Templeton’s unwillingness to invest in certain industries on moral grounds, including tobacco, alcohol, gambling, and pornography. When questioned about this policy in public, he tended to be circumspect, saying only that while he respected differences of opinion, he would follow what his conscience dictated. He did not ban his employees from smoking. But there was no doubt that he believed it was wrong of investors to encourage such human activity through buying the shares of companies that catered to those needs.1

Turning to what he called the economic virtues, one that stands out is his call for greater integrity in both business and governments, an idea he summarized as, “Pay your debts. Don’t cheat your neighbor. Don’t use false weights and measures. Keep your financial commitments.” Long before the current global sovereign debt crisis, he was urging the virtue of integrity on elected governments. “We have gotten used to the governments that run high deficits. Every day we hear about politicians that do not tell the truth about the state of the nation’s finances. Inflating the currency away through unsound political practices is a form of changing weights and measures.”

He went on: “Nothing can kill economic liberty like a widespread lack of personal integrity. Over time, people stop trusting others. When you cannot trust your neighbor, you cannot trade with him. Enterprise comes to a halt.” There has been no better example than the global credit crisis of what can happen when lenders and investment banks, for example, put short-term profit above their duty of care to their clients. It is for this reason that Templeton always favored countries such as Japan and Korea, in which business success is admired and society favors hard work and personal responsibility.

Financial markets, in turn, reflect the consequences of these shortcomings in personal behavior. Share prices, it is a simple matter to observe, are considerably more volatile than can be justified by changes in the economic fortunes of the companies that issue them. In an average year, the U.S. stock market historically has risen by around 10 percent per annum. Yet the average daily movement in the leading stock market indexes is around 0.8 percent. Given 240 trading days a year, that adds up to 192 percent a year of aggregate share price movements, or 19 times the average annual change in market values. The drivers of share prices in the short term, as is often said, are “fear and greed.” Those human faults, combined with institutional pressures, are ultimately what make the Templeton investment philosophy work. By driving share prices away from levels that are justified in economic terms, they create the opportunities from which dispassionate bargain hunting investors can profit.

The 16 rules laid down by Templeton are models of clarity and simplicity, and indeed, in many respects, simply statements of common sense. An interesting question to keep in mind, as already noted in the previous chapter, is why they appear to be so difficult in practice for many investors to implement. The most obvious explanations appear to lie, first, in the shortcomings of human nature and, second, in the extraordinary capacity of the modern institutional investment industry to encourage behavior that is antithetical to longer-term investment success. John Templeton’s set of beliefs about investment rested on the presumption that it requires considerable courage, confidence, and commitment to avoid being dragged into following “the herd” or “the crowd.” Yet it is no exaggeration to say that all the pressures that now affect professional investment managers and advisers combine to push them toward just such an undesirable outcome.

Invest for Maximum Real Total Return (Rule 1)

In whatever form Sir John’s investment rules or maxims were published, Invest for Maximum Real Total Return was always the first and most important. It makes the simple point that the only true measure of an investment’s performance is how much each dollar (or pound) invested produces by way of a return after taking account of all relevant deductions. The three most important deductions most investors face are: (1) taxation; (2) the change in the purchasing power of the currency they have used to make the initial investment; and (3) the cost of implementing an investment strategy, such as trading costs, professional fees, or (in the case of managed funds) annual management charges.

A simple example can explain the force of this maxim. Imagine two investments, A and B. Investment A, which is held in a taxable account, pays an annual income equivalent to 6 percent of the purchase price and generates capital growth at the rate of 20 percent per annum. Investment B is held in a tax-free account, but only pays an annual income of 4 percent per annum and grows in capital value at only half the rate of Investment A (10 percent per annum). Inflation is running at a constant rate of 5 percent per annum, and both investments are held for a period of five years.

As Table 4.1 illustrates, it is clear that Investment B is in fact a better proposition than A, even though the headline rates of return from the latter are higher. Because of inflation, the other point to note is that the real (purchasing power) value of both investments is notably less than the headline figures at the end of the five-year period. After five years, inflation of 5 percent per annum has the effect of reducing the value of money by more than a third.

Table 4.1 Comparisons of Investments

| Investment A | Investment B | |

| Assumptions | ||

| Invested | $10,000 | $10,000 |

| Income return (p.a) | 6% | 4% |

| Capital growth (p.a) | 20% | 10% |

| Tax rate on income | 25% | 0% |

| Tax rate on capital | 40% | 0% |

| Inflation (p.a) | 5% | 5% |

| After Five Years | ||

| Total income after tax | $2,747 | $2,442 |

| Capital after tax | $9,589 | $13,395 |

| IRR—excluding inflation | 17.8% | 21.4% |

| IRR—after inflation | 12.2% | 15.7% |

| “Real” value of investment after five years | $15,348 | $18,331 |

NOTE: Income returns assumed to grow by 10% per annum.

The emphasis on total return is important. Total return comprises the returns from a rising share price, together with the dividends paid to the investor. Contrary to what many investors appear to think, given their fixation with short-term share price movements, historically the dividend flow has been the most important factor in generating long-term returns. A company pays increasing dividends in the long run only if it can increase its profits. The value of a business is defined by the future profit stream, part of which is returned in the form of dividends and part of which is retained to finance future growth.

The real after tax total return that an investor receives, therefore, depends simply on how much he or she must pay to participate in the future stream of profits, whatever they may turn out to be, and in whatever combination of dividend and capital appreciation they happen to materialize. Pay a low price relative to valuation and the results are likely to be above average. Pay too much and the total return will tend to be poor. Investors can pay too much for a range of reasons, but the obvious ones are: (1) overestimating the future rate of growth; and (2) correctly estimating the rate of future growth, but paying too much for it. It is worth emphasizing that the study of the relationship between earnings and share prices described in the next chapter, which we use to explain why the Templeton method works, takes account of both inflation and corporate taxes.

Invest: Don’t Trade or Speculate (Rule 2)

Templeton’s second rule, Invest: Don’t Trade or Speculate, epitomized his approach. There are two types of investors who trade and/or speculate. The first type are those who do so deliberately, or for professional reasons. Day traders would be one example, proprietary traders at large investment banks and hedge funds another. The second type are those who do not realize that speculating is in fact what they are doing. In other words, they are investors who focus on picking stocks that they think are going to go up in price without having a sound analytical reason for expecting that result.

Speculation has its place in the financial system as a source of liquidity and what economists like to call price discovery, but it is a hazardous and, in Templeton’s view, foolish way to go about making money in the longer term. If, as the earnings study shows, short-term movements in share prices are effectively random, it follows that if you are investing on the basis of short-term financial results, then by definition you must be speculating in the formal sense of the word.2 Templeton’s conviction, based on many years of experience, was that seeking to make money by predicting short-term price movements was unlikely to produce consistently good results. Speculation, in his view, was little better than gambling—pointless when there was a more scientific way to approach the business of investing, and foolish given that the evidence that it works is so thin.

Many investors, it is fair to say, believe the exact opposite. They assume, whether implicitly or explicitly, that far from being random, short-term movements in stock prices are predictable, and that they can exploit that predictability. Many investors think that the stock market exhibits what statisticians term “autocorrelation.” This means the fact that a stock that has risen in price is more likely than not to continue to move in the same upward direction. The same is true for stocks whose prices have declined; having started to fall, the presumption is that they are more likely to continue in that direction than move upward. A professional term for this phenomenon is investing in momentum.

Recent studies have shown that there is some evidence that momentum strategies do produce consistent returns over some time periods.3 A number of hedge funds have sought to exploit this fact, some employing highly sophisticated mathematical formulas to try and capture profit from this effect. It is fair to say, however, that the results have been far from convincing. Using momentum, buying recent winners and selling recent losers, is far from being a surefire way to make money. On the contrary, the costs of implementing such a strategy can be high, particularly for private investors. And while the strategy can be profitable for some time, it has the nasty habit of producing out of the blue sudden sharp losses that are capable of wiping out most, if not all, of the previous gains for investors.

Speculation is dangerous not just because the outcome is unpredictable, but because it does not rest on any logical fundamentals, and it ignores the most important fundamental of all, which is valuation. Any investor who has no concern for valuation is effectively subscribing to the “greater fool” theory, the idea that there will always be somebody more foolish to buy your expensive stocks at an even higher price at a later stage. This is pretty close to a definition of gambling. The banking crisis of 2007 and 2008 showed that this pattern of behavior can extend to supposedly professional stewards of money. Banks and insurance companies such as AIG fell over themselves to insure enormous amounts of risk in return for very small premiums, while booking those premiums as profits. When the credit bubble burst, it wiped out all the accumulated profits on the transactions and created huge losses on top of that as well. The Internet bubble of 1999 to 2000 was another classic example where investors became transfixed by the way stocks of Internet companies kept on rising, despite never having made a profit, or in most cases having any appreciable prospect of doing so.4

The information technology revolution has encouraged the trend toward increased trading and speculation. The turnover of stocks on the main trading exchanges of the world has risen sharply over the last two decades. Computer-generated trading systems now account for nearly three quarters of equity trading volume in the United States, according to an official U.K. government report.5 The number of instruments that can be traded, notably derivatives, has also grown exponentially. The average holding period of stocks on the New York Stock Exchange has fallen from eight years in the 1950s to less than six months today. Advances in information technology mean that almost every day produces a new device or medium that allows yet more information to be delivered in “real time.” The financial world, it seems, has set a course that militates against the kind of patient, long-term investment that John Templeton advocated and practiced.

Remain Flexible (Rule 3)

Over the years John Templeton was given many flattering titles by the media. One of these was Dean of Value Investing. However, this kind of accolade is misleading, to the extent that it implied he was following a rigid set of specific investment criteria. “Value investors,” in the traditional sense, insist on limiting their stock purchases to stocks that meet certain specified criteria, such as a minimum return on assets, a maximum price earnings ratio, or a minimum level of dividend yield.

Templeton’s approach could not have been more different. Within a sensible logical framework he was willing to consider any method that might help to identify what he preferred to call “bargains.” In his analysis of individual stocks, he recognized that there were various combinations of value and growth that could produce a company that was “cheap” on a five-year forward earnings view. It could be a slow growing dividend-paying company whose shares were simply too low, or it could be a fast-growing company whose shares did not yet fully reflect that rate of future growth. “Never adopt permanently any type of asset or any selection method” was one of his maxims. Market conditions also change, and investors need to “stay flexible, open-minded, and skeptical.”

This did not simply apply to equities. For him all asset classes were potential investments. What mattered was whether they were cheap by reference to their intrinsic value. He was never solely wedded to investing in one asset class only. The same flexibility applied to the methods he employed for identifying and evaluating individual companies. Any restriction or bias, in his view, was liable to reduce an investor’s potential returns.6 A good example of this flexibility came in the spring of 2000 when Templeton, one of the greatest stock pickers of all time, advised readers of a financial magazine to switch their focus from equities to Treasuries (U.S. government bonds). For his own account and that of his foundations, he personally invested more than $100 million in a leveraged bet on long-dated zero coupon U.S. Treasury stock, funded by cheap borrowing in yen. He reinforced this position by taking a very large short position on technology stocks, which had become massively overvalued during the Internet bubble. Both positions produced handsome rewards; shorting the technology stocks made a profit of $90 million and the Treasuries produced a gain of more than 80 percent over the subsequent three years.7

Anyone who came into contact with Sir John would immediately realize his openness to new ideas. Many professional investors react angrily to the suggestion that there is a better investment method than the one they have chosen to be their own. Sir John, in our direct experience, was the exact opposite. For him, investment was a never-ending search for more and better ways of investing. He was willing to consider any potential method of identifying investment opportunities, however hare-brained they might seem at first sight.

A former colleague of one of the authors recalls walking into Sir John’s office to find him looking up at the sky, using a comb to guide his line of sight. The colleague knew at once that this had to be another one of what the office openly nicknamed “Sir John’s crazy ideas.” Sure enough, lying on his desk was an open book about sunspots and their impact on stock markets. Most professional investors would be incredulous that sunspots could be taken seriously as a guide to the behavior of stock markets. Yet Templeton was doing just that. He was genuinely interested in whether a relationship between the incidence of sunspots and stock market movements could be shown to exist. If there was, that did not mean that he thought that there was necessarily a causal relationship between the two. It might be that the incidence of sunspots reflected some more subtle, indirect effect, for example through their impact on the weather in crop producing areas. That, in turn, could be an important piece of information when considering the price of agricultural equipment manufacturers.

The point is that he was willing to explore the subject without dismissing it out of hand. He was always asking his colleagues to search for explanations for apparently bizarre phenomena. For his colleagues, such intellectual humility and openness to new ideas was striking, given how experienced and successful he had become as an investor. He also had a voracious appetite for new ways of identifying potentially cheap stocks. Colleagues lost count of the number of new stock screening ideas that he dreamed up or encouraged. For example, he had a view that pharmaceutical companies spent too much on research and development. One screen his funds followed as a result was based on adding back half of their R&D expense to see what difference that might make to their valuation.

Similarly, while a five-year forecasting period was the one he instructed his analysts to use, for reasons, as we have seen, which turned out to be very sound, he was also interested in making even longer term forecasts and using that as the basis for picking a small number of additional stocks that failed to qualify under the standard analysis. These stocks he termed “Q” stocks. To qualify a company had to be able to show earnings quadrupling over a 10-year period, which is equivalent to growing at a compound rate of 15 percent per annum.

Such openness to new ideas is often regarded as anathema in professional investment firms, where process has a tendency to take over from principles in investment analysis.8 Rules, hurdle rates, and checklists tend to proliferate. The larger the investment company, the more restrictive and rule-bound the process tends to become. Templeton’s investment philosophy was that value was based on the ultimate earnings power of a company and manifested itself in the long-term after tax profits a company could generate. Any number of analytical techniques can help in this search. Dogged adherence to just one technique, or one set of ratios, is unlikely to produce the best investment results. Yet this is the direction in which process tends to drive most professional investment firms.

If investment analysis were easy, we would not need to rely on emotional human beings. Instead we could simply build models to make decisions and then be ruled by a predetermined investment process. A number of so-called quant firms have been set up to do just that in recent years. They employ sophisticated computerized algorithms to make trading decisions. The difficulty is that the world does not repeat itself exactly and hence such trading strategies are vulnerable to sudden, unexpected blow-ups when the world ceases to behave in the way that it did. The collapse of Long-Term Capital Management in 1998 provides a notable example. The firm counted two Nobel Prize winners in economics and several stars from Wall Street among its employees. Its investment strategy was designed to exploit small pricing anomalies identified by sophisticated computer models; yet the historical relationships from which those anomalies derived collapsed overnight during a market panic triggered by the threat of an unforeseen event, a debt crisis in Russia. The problems that afflicted many quant funds in 2007, when the banking crisis started to unfold, provide another example.

Buy Low (Rule 4)

This is the exact opposite of momentum investing. Momentum investing invites investors to buy high and sell higher; buy the most popular stocks that everyone else is buying and stay for the ride. In contrast, Sir John’s most famous saying was that the best time to buy is at the point of “maximum pessimism.” This does not mean simply to buy anything where the share price is falling. What he was saying was that security prices are discounting mechanisms and if you can ascertain the value, then you should buy when the share price is out of line. By definition this was most likely to happen when sentiment was unduly negative, and that would therefore prove to be the point at which the best results could be obtained.

To illustrate this point, Templeton often liked to compare the investment industry with other professions. His reasoning went like this: “If 10 civil engineers tell you to build a bridge a particular way, then that is how you should build the bridge. If 10 doctors provide the same diagnosis then you should follow their recommended treatment. However, if 10 investment advisers tell you that a particular stock is cheap, then the last thing you should do is invest in it.” He did not mean to imply that any of the 10 investment advisers were lacking in intelligence or their dedication or ethics. It was simply an illustration that the market is a discounting tool, and if everyone thinks something has good prospects, then in all likelihood the share price will already have reacted and will no longer be cheap. “It is impossible to produce a superior performance,” runs the third of his maxims, “unless you do something different from the majority.”

Out of this comes the idea of contrarian investing or being different from the crowd. In our experience the concept of contrarian investing, as John Templeton understood it, is frequently misunderstood. For some it is taken as implying that investment should be conducted by figuring out what everyone else is doing and then doing the opposite. All sorts of tools, from sentiment surveys to monitoring investment flows, are available for those who are looking for information of this sort. Such indicators have their place. The main difficulty with adopting this approach is that it pays no attention to valuations. There are many occasions when the consensus will be right, not wrong. It is only when sentiment is adverse and valuations are low that being contrarian will pay off as handsomely as Templeton suggests.

The more logical process, in Templeton’s view, is to start with valuation and then move to portfolio construction. To the extent that the cheapest stocks are out of favor, then the portfolio this produces will look very different from whatever is “in vogue” with investment markets. It can therefore be safely described as “contrarian.” The key point, however, is that this is the outcome of a process driven by valuations, rather than contrarianism being itself the process. Since the search is for the companies with the greatest difference between their long-term value and their current share price, it is logical to expect portfolios to have a contrarian look and feel. However, the buy low rule does not mean buying shares just because they are low. Many shares fall for good reasons.

Search for Quality among Bargain Stocks (Rule 5)

Central to John Templeton’s investment philosophy was that when investing in companies, the sustainability of earnings was of critical importance. Since you were buying a long-term stream of earnings, the solvency and sustainability of those earnings are essential prerequisites. For example, it was unwise, in his view, to invest in businesses where the balance sheet was so weak that it was open to question whether the company would survive. Given the choice, his reasoning went, a “quality” stock should always outrank lesser companies as a potential investment. (As we have already noted, this was advice that he himself had deliberately ignored at an early stage of his career, with his speculative but ultimately successful foray into the stock market at the outbreak of World War II.)

What makes a quality company? Some of the characteristics he looked for were: a strong management team with a proven track record; evidence of technological leadership; an industry with continued growth potential; a respected and valuable brand; and low-cost production. In essence, he was looking for companies that enjoyed a sustainable competitive advantage within a supportive environment. While an investor is unlikely to find all these characteristics in one company, there should be at least a number of identifiable sources of competitive superiority, just as you look for three or four stars in a restaurant.

The problem with buying quality stocks is that their quality characteristics tend to be obvious to all investors. As such their superior qualities are already likely to be reflected in their share price. It follows that the most likely time investors have an opportunity to buy quality stocks at bargain prices is when the whole stock market has become infected by fear and share prices are falling in an indiscriminate manner. For most of the rest of the time, when deciding whether to buy a quality stock, the investor is faced with deciding whether the price at which it is available is sufficiently attractive to justify paying for the quality on offer. It is a trade-off between risk and reward.

Quality stocks generally carry much less risk in terms of their future profit profile and hence their valuations are not subject to so much uncertainty. So long as the valuation is reasonable, they are then the preferred investment. Stocks where there is greater doubt over future earnings are higher risk and would count as bargains only if the potential reward is commensurate with the risk being taken and can be included in a diversified portfolio. Quality stocks are not without risk to shareholders even if they have a predictable profits stream; pay too much for them and investors are still at risk of losing money.

Buy Value, Not Market Trends (Rule 6)

Another key component in Templeton’s investment approach is that a stock market is simply the aggregation of the underlying companies. It is not an entity in its own right. Furthermore, he argued, “the market and the economy do not always march in lock step. Bear markets do not always coincide with recessions.” His conclusion, therefore, is, “buy individual stocks, not the market trend or economic outlook.” Any investor with more than a few years’ experience will have learned the wisdom of this observation. The well-known saying that “bull markets have to climb a wall of worry” is just one example of how share prices often seem to be moving in the opposite direction to that which the news seems to justify. Witness also the often bitter complaints from company executives that their share price is failing to reflect their most recent results. Templeton from an early stage was also dismissive of economists’ ability to make useful forecasts, something that he used to justify his non-forecasting method of asset allocation for clients of his firm.

In all these cases the underlying explanation is the same. When you invest in a company, you are buying a potential long-term stream of earnings. Few if any companies, though, have earnings that grow in a straight line. Revenues, margins, and profits vary with the economic cycle, irrespective of their underlying or long-term rate of growth. Simply extrapolating recent results may as a consequence often make a company look incorrectly expensive or cheap. A recent discussion with the company Applied Materials provides a good example of this phenomenon.

Applied Materials is a company that would satisfy almost all of John Templeton’s quality criteria. It supplies manufacturing equipment for producers of advanced semiconductors, flat panel displays and solar photovoltaic products. It has a rock solid balance sheet, strong management, technological leadership, and a product portfolio in industry segments that are experiencing steady growth. But its earnings are also cyclical because its customers delay or defer orders when semiconductor demand falls.

The company’s profit margins fall when demand falls, and rise when demand recovers, but given the rapid nature of change in the IT business, these delays tend to be short-lived. As a result, over very short periods, for example nine months, since orders are already in production, it is relatively easy to predict future earnings. Given the company’s competitive advantages, the same goes for the long term. However, for periods between nine months and five years, earnings are virtually impossible to predict, given the volatility of orders arising from customers’ delayed or deferred decisions. Simply extrapolating recent results is therefore almost certain to produce the wrong result.

For the modern investor the difficulty of identifying long-term value in stocks is compounded by the widespread availability of information that appears relevant, but in practice distracts from the main objective. Surprisingly little of the information that proliferates across Bloomberg screens and Internet sites relates to whether a stock is cheap or not. Wonderful products, increasing market share, telegenic and charismatic CEOs, new and exciting markets—all these are interesting pieces of information, but most of them are tangential to the central issue of whether a stock qualifies as a bargain. Even the most experienced professional investors struggle to say whether a stock is cheap. What you hear, as often as not, is not a statement about absolute or intrinsic value. It is a statement about relative value.

Think for a moment about the following commonly heard statements: “The company is going to come in ahead of earnings expectations and therefore it is cheap”; “The company trades at a meaningful discount to others in its sector and therefore it is cheap”; “The company is trading at a discount to historic valuations and therefore it is cheap”; “If you value the other divisions of this company like their competitors, then you get this division for free and therefore it is cheap”; “The company has major growth opportunities in the most exciting growth areas in the world and therefore it is cheap”; “The company has the best, most visionary CEO in the business, the man who almost single-handedly built the industry, and therefore it is cheap”; “The company has the leading brands in all its sectors and therefore it is cheap”; “The company was the first into this technology and has clear intellectual leadership and therefore it is cheap.” Every one of these statements contains a comment that may or may not be true, followed by the same non sequitur.

The simplest explanation for the myopia of investors lies in the complex matrix of intelligence and emotion that shapes human behavior. Detachment is difficult and the power of conventional wisdom makes it difficult to deviate from it for any sustained length of time. John Maynard Keynes famously said of professional investment: “Worldly wisdom teaches that it is better for reputations to fail conventionally than succeed unconventionally.” In addition there is the phenomenon known as business risk to consider. For many professional investors, fear of being fired is a dominant concern in determining how they behave. Experience shows that investment managers are more likely to be fired if they deviate significantly from what other professional investors are doing. In the interests of self-preservation, the path of least resistance is to continue behaving like the majority of other investors.

It is the source of such common refrains as these: “It does not matter if I am right, by the time it comes true I will have no clients,” or “My competitors all own these stocks and if I do not I will be left behind; I have, however, taken a prudent position of being underweight,” and one of our personal favorites: “These stocks may look expensive, but they always trade at these valuations.” In essence they are all saying the same thing. It is: “Although I know these stocks are expensive and hence will ultimately lose money, it suits me to do something that will hurt clients because in the short run it will be better for me.”

It is certainly the case that the pressure on underperforming fund managers can be intense. However, fund managers are very well paid and enjoy a career that is virtually free of physical danger. It is human nature not to take heed of Templeton’s view that investing other people’s money is a “sacred trust.” A professional investor who believes that a stock is expensive should not own that stock, period. All other justifications are self-serving. This does not mean that investors who follow Templeton’s investment principles will not end up owning stocks that turn out to be expensive, rather than bargains.

As we have seen, Templeton himself thought that anyone who gets six out of ten investment decisions right was well on the way to beating the market. In analyzing future earnings, mistakes are inevitable, however good the analyst. Forecasting the future is difficult and you cannot get anything correct without accepting that you will also get some things wrong. Knowingly buying an expensive security in order to protect a personal career stands in quite a different light to making an honest mistake in analysis. Professional investing, to reiterate Templeton’s view, is ultimately a matter of personal morality and integrity.

Diversify Your Holdings (Rule 7)

John Templeton had distinctive views on the importance of diversification. To any potential investor, he extolled the benefits of spreading portfolios across a range of different types of investments. The obvious common sense reasons include the risk of unexpected external events and the fact that different types of investments react differently to changes in the economic and political environments. Investing across a number of different countries is clearly a defense against something bad happening in any one of those countries, and similarly for individual stocks. He had no specific rules about how many stocks were needed to achieve the necessary amount of diversification. We have seen how the Templeton Growth Fund’s portfolio was much less diversified in its early days than later, when it had become so much bigger in size. However, for him, the greatest risk against which diversification guarded was that the analysis preceding an investment might simply be wrong. In his words: “The only investors who shouldn’t diversify are those who are right 100 percent of the time.” In practice, no such paragons exist. By the same token, the less confident an investor is in his or her methods, the more diversification is justified. There could never be a justification, however, in his view, in buying overvalued stocks purely because they had different characteristics, or were components in an index. That kind of diversification—diversification for its own sake, or index-hugging—made no sense to him.

Do Your Homework (Rule 8)

Sadly, investment is hard work. It is not based on “gut feel” or “intuition.” John Templeton subscribed to the golfer Gary Player’s maxim, “the harder you work the luckier you get.” One of his own maxims was, “achieving a good record takes much study and work, and is a lot harder than most people think.” In investing in a company you are buying a future profits stream or the assets to produce one. There are no shortcuts to obtaining this information. Company analysis is relatively straightforward in a technical sense. Almost anyone can learn to read a set of financial statements and interpret what is contained within them. It is much harder to try to figure out how an industry may evolve in the future and how a particular company will adapt to that changing environment. However, when you invest in an equity, that is what you need to do. That takes long and serious study.

John Templeton set his own standards exceptionally high in this regard. For most of his life, he worked 12 hours a day for at least six days a week. All his employees knew that he would pack as much as possible into every working day. Jim Wood, who helped set up an investment counseling business for the Franklin Templeton group following the sale of Templeton’s fund business in 1992, recalls how serious, short, and intense meetings with the head of the organization invariably were. Templeton’s diary was always filled with meetings, each one scheduled to the nearest minute. In his days as a fund manager he invariably carried a set of research reports in his briefcase to fill in any time caused by delays while traveling. It was known that he kept a pair of pajamas behind the sofa in his office, just in case work kept him late there, as it often did.

Well into his eighties, despite his many other commitments, he continued to review and challenge the work of his research team, noticing much and missing little. “Because he always worked so hard himself, it made you feel that you would somehow be letting him down if you did not do so, too,” Wood recalls. His focus on research stands in contrast to the way that some other investment firms are managed. Far from employees being desperate to be analysts, in many firms the analyst position is typically viewed as an entry level position, with limited status. It is a role which, if you are to advance a career, you will soon want to leave behind for others. Few CEOs of the largest investment firms have recent experience of analyzing a stock, and some have never even attempted it. Yet for Templeton, to be doing analysis was the highest calling—and as such something that called for long hours and a relentless search for new and better information.

The reason why hard work matters so much in investment is that the task is essentially unlimited. There will always be more companies to analyze, more details to assimilate, and more news and fundamental changes to a company’s operating environment to understand. The investor does not have enough time in the day to do it all. At the same time, waiting for perfect information before making a buy or sell decision risks being left behind, as by then the market is more than likely to have incorporated the thrust of the analysis into the price of the shares. The role of the analyst is to put together enough pieces to perceive the overall picture and then to judge how much impact the missing pieces could have. It is a question of balancing risk and reward. If the picture is very clear and unlikely to change much, then the risk is low and a slightly higher price can be paid. If the picture is still hazy and the range of outcome is wide, then this is a higher risk proposition where investment may be inappropriate.

Aggressively Monitor Your Investments (Rule 9)

If investing is about a long-term approach does this mean that we buy and hold and then leave our investment in a dark room to grow? As Sir John frequently noted, the world is constantly changing. As a result, it is vital to monitor investments closely once they have been made. His view early in his career was simply that investments should be sold when they become “expensive.” His typical holding period, as we have seen, was four to five years. He recognized that it takes time for the value in a cheap stock to be reflected in a rising share price. He rarely caught cheap stocks exactly at the bottom of their pricing cycle. Quite often a company’s shares might fall 25 to 30 percent after he first acquired a holding. That did not bother him: If his analysis was right, the performance would follow eventually. If the analysis turned out to be wrong, however, the stock should be sold. Some investors proudly declare that they never sell investments in good companies.

This was not Templeton’s opinion. Just as any company could become cheap, so any company could become expensive and therefore cease to be a sensible investment. Later in his career, Templeton evolved a rule that a stock should typically be sold if another stock could be found that was at least 50 percent cheaper on fundamental grounds. The important thing was to keep the portfolio under regular review and be prepared to take decisive action when market conditions created new opportunities. The same discipline needed to be applied to selling as to buying. The reason was, he liked to say, “when sentiment changes, it changes very suddenly, and if you are not invested, you will miss out on a large proportion of the returns.”9

Although the focus on finding bargains remains constant, having a long-term investment horizon also requires the investor to watch out for broader changes in the world. The technology sector provides the most obvious examples of rapid evolution. In the 1970s there was much talk about centralized computing, with huge mainframes being used to distribute computing power to dumb terminals. By the 1990s all the companies whose share prices had soared on this expectation were dropping like stones, as the rise of the personal computer now had the opposite effect of decentralizing computing power. Today the centralized model has again gained traction, with cloud computing becoming a hot area for investors.

Big changes have also been taking place in the global balance of power. In less than 40 years, for example, the United States has moved from being the world’s largest creditor nation to becoming its largest debtor. The biggest incremental purchasers of luxury goods are now in the East rather than the West. Commodities have gone from being scarce to being abundant and are now scarce once more. Such changes are not themes that the investor should be trading, but they will inevitably have a bearing on the earnings potential of individual companies, and as such they need to be monitored.

Don’t Panic (Rule 10)

The corollary to selling stocks when they are expensive is to buy them when they are cheap (Rule 4). In John Templeton’s words, “the time to sell is before a crash, not afterwards.” If you have been caught by a sharp market decline, then if there were good reasons to have held the stocks before the crash, there should be even better ones afterward. That means, he continues, “the only reason to sell them now is to buy other, more attractive stocks. If you can’t find more attractive stocks, hold on to what you have.” This rule is a perfect example of Templeton’s simple but remorseless logic. One of his favorite techniques was to determine a price at which he would be willing to buy a range of stocks and leave those orders with a broker to execute should the prices of those stocks fall to the level at which he regarded them as cheap on a five-year view. That way he could be sure that his decisions would not be influenced by an emotional response to sudden sharp movements in the market, and he would be buying when others were gripped by panic.

While it may appear trite to say that the time to sell stocks is before a crash, doing so is psychologically difficult. The time to sell a stock is when it is expensive. The problem is that there is a reasonable chance that it will become more expensive. Indeed, this is the whole principle of momentum investing. The Templeton investor has to be prepared to watch a stock that has been sold continue to go up, often for some considerable time, and possibly alongside another recently purchased stock that is going down. One of Templeton’s most frequent experiences was to see his bargains become cheaper after he had first bought them. Since his methodology was rooted in valuation, rather than sentiment, he rarely caught the precise lows of any stock he bought, and frequently sold, too soon. By the same token he often sold out of positions on the grounds that they were overvalued long before the market itself corrected to a more sensible level. His decision to sell out of the Japanese market in the early 1980s, at least 10 years before the Japanese market finally peaked, was by no means the only example of this phenomenon.

The payoff to this rigorous valuation discipline comes, however, when markets experience one of their periodic blowoffs. It is no accident, as we have seen, that the key to Templeton’s long-term outperformance of the market was his superior performance during bear markets. Not only is a portfolio of “cheap stocks” almost bound to fare better than one built around momentum in such periods, but the discipline of selling when stocks become expensive results in the investor having cash to invest when prices in an overvalued market fall sharply and indiscriminately, creating new opportunities. Sir John’s investment discipline in this respect was critical in helping to create his track record. It was a lesson that, as we have seen, he regularly imparted to his clients as an investment counselor and one that time and again he put into practice during his career as a fund manager.

As a fund manager, there were several occasions on which he moved a significant proportion of his portfolio into cash and bonds because stock values had risen too far and he was no longer able to find sufficient bargains. To be in that position requires not just analytical skills, to know when a market has become expensive, but great strength of character to ensure that the discipline is not abandoned when the market does subsequently fall sharply. The same thinking lay behind the use of the Yale formula in his days as an investment counselor. Buying when others are despondently selling and selling when others are greedily buying, to quote one of his favorite maxims, “requires the greatest fortitude, even while offering the greatest reward.”

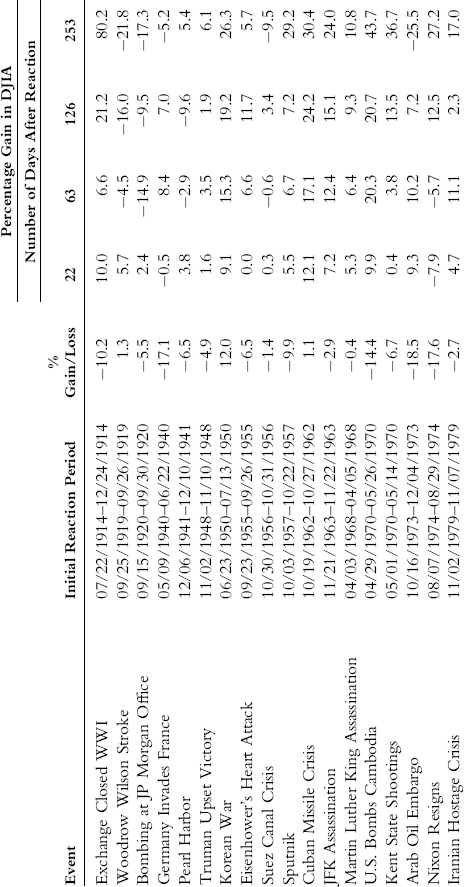

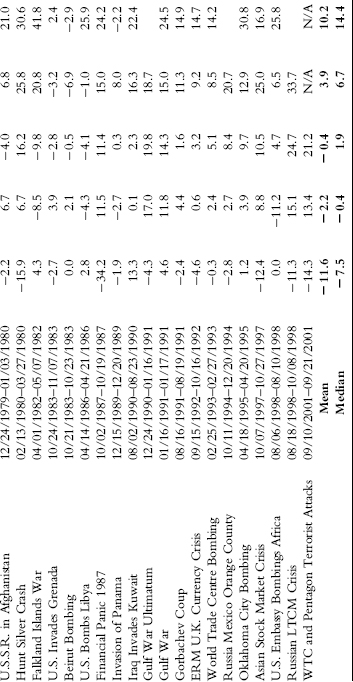

One of the central exhibits in any Templeton investor’s armory is the evidence of how the stock market reacts to traumatic events, such as the 1929 and 1987 market crashes, or external shocks such as the 9/11 terrorist attacks on New York and Washington (see Table 4.2). What is striking from this analysis is how an immediate panicky reaction to the event is often taken to unwarranted extremes as investors race for cover. The market often recovers well within a number of weeks, typically regaining a good deal of the previous loss. As selling in crisis periods can be indiscriminate, stocks often get beaten down across the board. For a disciplined investor, with rigorous valuation criteria, this creates the opportunity for profitable participation in the subsequent recovery.

Table 4.2 Crisis Events and the Dow Jones Industrial Average

Source: Ned Davis Research. Reprinted with permission.

Learn from Your Mistakes (Rule 11)

Investment analysis is an evolutionary process because the world itself is constantly evolving and it takes time to gain the necessary experience and historical perspective to learn how to assess absolute value in stocks and how the corporate environment is likely to impact the future earnings potential of companies. Anyone who worked for Templeton was aware of his constant search for new insights into the way the world was evolving. Nothing was more important, in his view, than to study and to understand why reality so often turns out to be different from what faulty analysis expects. Hindsight is a wonderful teacher, but in many investment organizations the need to learn lessons is frequently lost in a hunt for scapegoats to blame when things go wrong. This was not Templeton’s way. He was his own taskmaster. While working for the company in the 1990s, for example, one of the authors observed firsthand how much effort Templeton put into trying to work out whether he was wrong to have dumped his Japanese stocks as early as he did, a decision which, as we have seen, led to one of his longest periods of relative underperformance. This was only one of many examples of how Templeton sought to learn from his own mistakes. It is also another way of saying that having the right investment philosophy is not itself sufficient to guarantee success, as many “how to” investment books effortlessly imply. Implementation is the key, and while setting out to buy low and sell high is simple, it is not easy to do.10

Begin with a Prayer (Rule 12)

Sir John used to start meetings with a prayer. Even for those who are not of a religious disposition, there was nothing to object to in the words he spoke. All that he asked for was to be able to work to the best of his ability to help his clients. “We don’t pray that a particular stock we bought yesterday will go up in price today, because that just doesn’t work,” he told his biographer William Proctor. “But we do pray that the decisions we make today will be wise decisions and that our talks about different stocks will be wise talks.”11 If nothing else, opening with a prayer helped him to create an atmosphere that was conducive to the kind of calm and deliberate analysis that he held to be essential to good investment decision-making. Many of his colleagues recall finding themselves motivated to work harder for fear of failing to live up to their employer’s own, much higher personal standards.

Outperforming the Market is Difficult (Rule 13)

Although his own track record as an adviser and fund manager was proof that it could be done, by the time of the sale of his fund management business to Franklin, John Templeton was well aware of the difficulties both individual investors and fund managers face in seeking to outperform the market on a sustained basis. As an investment counselor in the 1950s, it was natural—and indeed orthodox—to claim that his firm’s use of the Yale method, allied to successful stock picking, was capable of producing better than average results for his clients. The marketing materials of the Templeton Growth Fund from the 1970s onward made extensive use of his track record to promote sales of his fund. It was not until this period that the first academic studies of mutual fund performance began to expose how hard in practice it had become for professional fund managers and advisers to outperform broad market indexes over anything but relatively short periods.

This discovery led in turn to the launch of the first index funds and the appearance of a new industry of consultants and other intermediaries whose sole job was to analyze and rank professional investment performance, not just in absolute but also relative terms. In the 30 years between 1960 and 1990, the stock market moved from being a market dominated by individual investors to one dominated by large investment institutions, such as pension funds, insurance companies, and mutual funds. The abolition of expensive fixed commissions, in 1973 in the United States and 1986 in the United Kingdom, coupled with rapid improvements in information technology, globalization, and the arrival of derivatives, was meanwhile prompting a quite remarkable increase in both the volume of trading and the degree of competition in international securities markets.

When Templeton first outlined his investment maxims, in the early 1980s, there was little mention of the difficulty of beating the market. By the 1990s, however, it was no longer possible to dispute the fact, which had become extensively chronicled in academic and professional research. To admit as much was therefore doing no more than accepting a basic fact of life that now confronts all investors, both professional and private. Toward the end of his life, John Templeton himself said that he doubted whether he would now be able to produce the results he did in his heyday as a fund manager, given the greater degree of competition across the industry and the increasing pressures faced by fund managers to produce short-term results and conform to consensus thinking. As a businessman, while he remained confident that his investment philosophy remained as valid as ever, he was very conscious that the investing environment had also changed, making it harder for professionally managed funds to outperform the market as dramatically over the long run as he had been able to do. While he was clear that index funds could never produce as good results as the best active investors, he was equally careful not to say that they did not have their uses.

In an interesting memo to his colleague Mark Holowesko, written in 1993, soon after the sale of his business to the Franklin group, he underlined some of the implications that the new environment had for a fund management business. He argued that it made sense for the firm to offer a range of funds that each had different allocations to equities. Why? “Firstly, it enables the dealers to offer to the public at all times some kind of fund which fits the wishes of the public. Secondly, it multiplies the chances that one or two or more of the Templeton funds will be at the top of the performance table at different times and thereby attract vast free favorable publicity.” A similar argument applied to the question of whether funds or portfolios should be split between different managers. Templeton’s clear view was that there should always be one lead manager for every fund, as this would increase the diversity of the firm’s offering and “thereby multiply the chances that one or two or more of the Templeton funds can be at the top of the performance list in all varieties of market conditions and fashions.” For all his high principles, he was nothing if not pragmatic as well.

Success is a Process of Continually Seeking Answers to New Questions (Rule 14)

There is not much to add to Sir John’s comments on this: “An investor who has all the answers doesn’t even understand all the questions. A cocksure approach to investing will lead, probably sooner rather than later, to disappointment, if not outright disaster. Even if we can identify an unchanging handful of principles, we cannot apply these rules to an unchanging universe of investments, or an unchanging economic or political environment. Everything is in a constant state of change, and the wise investor recognizes that success is a process of continually seeking answers to new questions.” As we have seen, this is an axiom that he himself continued to observe right up to the end of his life. The conditions that prevailed in the first decade of the twentieth century were very different than those of the 1940s or 1950s. New industries, such as computing, inevitably required new methods of analysis. At the same time, styles of investment also come and go. There are periods when large stocks do better than small stocks, and vice versa. The same goes for value and growth. It was central to Templeton’s view of the world that the investor had to adapt accordingly. The relevant maxim here is: “If a particular industry or type of security becomes popular with investors, that popularity will always prove temporary and once lost, won’t return for many years.” It is the nature of the investment business that it has a constant need for new ideas or instruments that it can market, and investors need to be vigilant in order not to fall into the easy trap of following fads.

There is No Free Lunch (Rule 15)

This has become a common saying in financial markets, and is a principle that underpins a good deal of modern regulation of financial markets. Investors rarely get something for nothing, even if they are unsure or unaware of what the cost is at the time. The saying is allied to the notion, well documented in research, that in general there is an inverse correlation between risk and return. The higher the risk of an investment, the greater the return that investors will require by way of compensation for owning it. A central tenet of modern portfolio theory is that diversification is one of the few free lunches in investment, as a portfolio of negatively correlated investments will reduce the volatility of the portfolio without necessarily reducing the return. Templeton’s comment on this was laconic: “Everyone should read about modern portfolio theory, but honestly they are not going to make much money with it. I’ve never seen anybody that came up with a really superior long term record using only modern portfolio management.”12 His point here was not that diversification was wrong, but that the notion that building portfolios on the basis of unreliable and irrelevant statistical inputs, such as historical volatility, was doomed to failure. He was always at pains to impress on his colleagues the need to avoid allowing their implicit or explicit biases to influence how they invested. In his view, there were no shortcuts. Proximity to a company, analyst recommendations, tips from friends, use of its products; all these are terrible reasons to buy a share. Investments should only be made, in his view, after extensive due diligence.

Be Positive (Rule 16)

Virtually every speech ever made by John Templeton focused on the positives of life, and he wrote a series of books encouraging others to share this philosophy in the way they organized their lives. His speeches would document the great advances in literacy, modern medicine, living standards, and mortality rates that had been achieved in his lifetime. He had great faith in the ability of mankind to triumph over adversity, but worried about how many people seemed prone to negativity. When a friend of his launched a new newspaper to counter the media’s obsession with bad news, it lasted less than three months, an outcome that he regarded as a sad reflection on human priorities. This carried over directly into his approach to investment. He had huge faith in the power of human ingenuity, if protected by the law of property rights. He believed economic progress had been accelerating since the Industrial Revolution and that it was a paradox of the human psyche that we could simultaneously remain gloomy about prospects while simultaneously enjoying the benefits and fruits of that progress.

Any investor who reads the rules, or the maxims, that John Templeton laid down is bound to be struck by their simplicity. They are not difficult to understand. He himself referred to investment as being, for the most part, common sense. In the first chapter, we noted how his colleagues invariably allude to the way that he was able to make complex issues seem so straightforward. The fact that so many of his maxims remain relevant despite first being coined more than half a century ago is a testament to the power and timelessness of his insights. Yet there is no evidence that we can see that they are any more widely observed today than they were in his time. The increasingly short-term focus of modern professional investment stands in diametric opposition to the principles and approach that John Templeton both preached and practiced. Modern portfolio theory has failed, on the whole, just as he predicted, to produce consistently superior results. The explosion of information made possible by the Internet and instant global communications has empowered, but not yet enriched, private investors. The opportunities to profit from a Templeton approach to the markets are therefore just as great today as they were in the past, but the task of putting them into practice is no easier.

Notes

1. Templeton of course paid for part of his education by gambling at the poker table, but this was out of necessity rather than rational choice. He gave up the game after university and appears never to have played it again.

2. Unless, that is, you have some source of superior information. This may legitimately be the case for some professional investors, such as market makers. Trading on insider information is of course illegal.

3. See, for example, the analysis published by three London Business School professors, Dimson, Marsh, and Staunton in their Global Investment Returns Yearbook (2009 and 2010 editions), or the published work of Professor Andrew Lo of MIT’s Sloan School of Management.

4. The phenomenon of bubbles is examined at length in a previous book by one of the authors, Engines That Move Markets by Alasdair Nairn (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2002).

5. The Future of Computer Trading in Financial Markets, Government Office for Science, 2011.

6. In his later fund management career, Templeton imposed a restriction against his funds investing in so-called “sin industries,” such as tobacco, gambling, and alcohol. He did not dispute that this was potentially damaging to the fund’s returns.

7. There is an excellent account of these two trades in Investing The Templeton Way, by Lauren Templeton and Scott Phillips (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2008), Chapters 6 (technology stocks) and 9 (bonds).

8. This is not necessarily their fault. Consultants and other intermediaries who advise institutions on their allocation of investment funds devote an inordinate amount of time and effort to testing a professional investment firm’s process.

9. Investing the Templeton Way, 57.

10. Simple, Not Easy (London: Doddington Publishing, 2007) is the title of an excellent book by the fund manager Richard Oldfield, which describes amusingly how the business of professional investment rarely achieves in practice what it claims to be able to do.

11. Proctor, The Templeton Touch, 95.

12. Norman Berryessa and Eric Kirzner, The Templeton Way, 52.