Chapter 6

Past, Present, and Future

One reason for including so many examples of John Templeton’s letters to his clients in this book is to enable readers to see for themselves how he thought about the business of making investment decisions. Although market conditions are very different today than they were in the 1940s and 1950s, the process of thought required to make sense of today’s world is, in essence, still much the same as it was then, just as the analytical process needed to pick individual stocks successfully remains similar to that which John Templeton first put into practice 60 years ago. His success was not so much a matter of analytical technique as a function of the simplicity, power, and consistency of his investment philosophy. This can best be appreciated by immersion in his way of thinking, for which the original source material of his own writing remains the best guide.

The memos reproduced in the text and the Appendix lay bare both the clarity of his thinking and the essence of his investment philosophy, which, as we have seen, while it was refined in detail, changed remarkably little throughout his long career as an investment professional. In a letter to clients dated August 12, 1958, for example, he pointed out that the firm had first printed a comment about the rewards of contrarian investing in its original brochure 20 years earlier. The same thought (“To buy when others are despondently selling and to sell when others are avidly buying requires the greatest fortitude and pays the greatest ultimate rewards”) was one he was still using four decades later! While unfailingly on the lookout for new ideas and techniques, he was nothing if not fundamentally consistent and confident in his beliefs.

While readers can make up their own minds about the continued relevance of his thoughts and insights to the world today, in this final chapter we offer some personal conclusions about why John Templeton was as successful as he was; highlight the key lessons that we think can be drawn from his life and career; and speculate as to what, were he still alive, he might have to say about the state of the world as we enter the one hundredth anniversary of his birth, a year in which the world continues to confront the painful and enduring consequences of the global financial crisis of 2007 and 2008.

The evidence we present on the performance of the Templeton Growth Fund confirms that John Templeton was, by any standard, one of the most successful and influential investors of the modern era. His track record, particularly that which he put together in the two decades following his move to the Bahamas in the late 1960s, rightly stands comparison with that achieved by other great money makers such as George Soros, Warren Buffett, and Julian Robertson. Outperforming the market by 6.0 percent per annum during these years, and by 3.7 percent per annum over his full tenure as manager of the fund, remains a remarkable achievement, not least because it was achieved without the use of debt to leverage returns. For much of the period, he operated largely on his own without the benefit of specialist research support.

The fact that he achieved such consistent outperformance without exposing his investors to a loss in either nominal or real terms over any continuous five-year period during his time at the helm of the Templeton Growth Fund is the mark of someone who, we assert, can be said to have found the Holy Grail of professional investment—above average returns with below average risk. The track record is one that any investor today should be thrilled to emulate. It is a fair bet that among comparable professional investors, for whom the pressures to pursue short-term performance are now so great, his performance during the Bahamas years may never be beaten. In later life Templeton often said himself that he would find it difficult to reproduce his track record now because of the pressures fund managers face to conform to the market’s expectations. Private investors, paradoxically, have a much better chance of doing so, since the necessary information sources are much more readily available than they were in the past, and they are—in theory at least—potentially immune to the conformist demands of Wall Street and the city of London.

There was nothing elaborate or complicated about his investment approach. Nothing could be simpler in principle than buying cheap stocks and holding them until their intrinsic value has been appreciated by the market. The formula is as old as the business of investment itself. The skill comes not so much in absorbing the philosophy, but in having the nerve and ice-cool temperament to execute the policy successfully over a long period of time. If it were easy, many more investors would have done as well as he did. In practice, only a handful of professionals can plausibly claim to have done so with anything like the same consistency, while the majority of private investors, we know from several studies, struggle to beat the market over any but the shortest periods.

Many important components contributed to Templeton’s success in an endeavor where so many others have failed. One critical one was his insistence that the stock picker’s task is to look forward to the future sustainable earnings potential of a company, and not simply back at its historic ratios. While it is standard practice today to look at projected earnings, few investors take the analysis as far out as five years, which was Templeton’s preferred time frame. Picking stocks that are trading on low P/Es relative to their five-year forward earnings is, as we have demonstrated in Chapter 5, a method that is destined to produce superior results if it can be implemented effectively.

To get the best results reliably, to put this another way, it is imperative that the investor ask the right questions. While Templeton remained curious and open-minded to the end of his life about the merits of alternative investment approaches, he never lost his faith in what he believed were the right questions to ask. Indeed, it was his confidence that his methods were sound that enabled him to act so decisively against the prevailing opinions of the day. Many investors, in his view, are doomed to failure precisely because they are pursuing answers to the wrong questions. Relying on historic ratios, or one-year forward price-earnings forecasts, for example, is a method that he regarded as being incapable of producing sustainably good results. Bowing to the prevailing market opinion of the day was an easier, but lazy, option. This can be traced back to his view that the most important imperfection in market behavior is the short-termism of most market participants.1 This in turn is ultimately the result of the temperamental, institutional and emotional biases to which all human beings, whether they work alone or in organizations, are susceptible.

It is naïve to believe that calculating a five-year forward P/E ratio, let alone a 10-year forward P/E ratio, which Templeton wanted for his so-called Q stocks, is an easy task. Even the best and the brightest analysts are likely to make mistakes in attempting it, since there are so many uncertainties involved. Creating a working environment that contributes to the avoidance of mistakes is therefore central to any investment firm’s process. The task requires a mixture of different analytical skills, some technical and some intuitive, some bottom up, some top down. In Templeton’s view, the analytical task is central to effective stock picking. It cannot be readily or effectively delegated. Nor, however, can it be avoided.

John Templeton cannot easily or usefully be labeled as either a value or growth investor. Such labels create artificial distinctions that he regarded as largely irrelevant to success or failure as a stock picker. As a fund manager he would happily buy both value and growth stocks. His only criterion was that a stock should be cheap at the point of purchase. In theory, cheap could be any combination of current growth and earnings multiples, provided that the multiple of five-year forward earnings that it implies is a realistically low number. The biggest crime an investor can commit, in his view, is simply overpaying. He himself rarely used the term value investing. Indeed, his public profile was that of a growth investor, as the name of his fund suggested. In the 1950s he was so impressed by the potential of fast-growing companies in certain sectors that he and his colleagues launched a major research project to identify the shares of the fastest growing companies. But he was also content to buy slow-growing companies if their earnings were sustainable and the price on offer was sufficiently low to compensate.

The issue with growth companies is always (1) whether the growth can in fact be sustained into the future; and (2) whether those improved earnings have already been discounted at the time of purchase. All the evidence suggests that investors tend to overpay for growth. Our study suggests that paying more than 11 times five-year forward earnings for any kind of stock will be an unrewarding exercise; and that to beat the market convincingly lower ratings still are desirable. In the Templeton philosophy of investment, valuation is ultimately the constraint that limits any investor’s capacity for making consistent and repeatable gains (or, as Warren Buffett likes to say, “Price is what you pay. Value is what you get.”).

An equally important factor in determining the success or failure of a stock picker is whether he or she has the temperament and patience to wait for superior results to come through. By birth and upbringing, it is clear that John Templeton was blessed with a temperament in which patience, forbearance, and confidence in the face of adversity were constants. They contributed greatly to his success as a professional investor, and by the same token the lack of these qualities is often the reason that other investors fail to do as well as they should, let alone as well as they feel they are entitled to expect. It is tempting to draw a parallel with those who achieve the highest pinnacles of excellence in sport. Talent and technique can take you only so far; experience, commitment, and emotional intelligence are also essential.2

Allied to Templeton’s belief in the primacy of intelligent stock picking was a conviction that investors should adjust their exposure to the stock market in the light of its prevailing valuation. If there are not enough cheap stocks to buy, then the investor should simply park his or her money in cash and bonds, and wait for the next turn in the cycle to come around, when new opportunities to buy shares at attractive prices will inevitably arise. Holding cash has two distinct advantages in overvalued markets: (1) it avoids losses as and when valuations revert to their long-term average, and (2) those with cash on hand at that point alone are in a position to profit when the market finally turns. Templeton was an assiduous student of bull and bear markets, as well as of the business cycle. As we have seen, it was his willingness to steer clear of stocks at the onset of bear markets that was chiefly responsible for his long-term track record of outperforming the world market index.

The discipline to sell shares when the market had become overvalued and to buy more when prices had fallen to a level where they were “cheap” was integral also to the way he approached his responsibilities as an investment counselor. (It is notable, however, that his methodology was based on historic valuation ratios, not on the forward-looking measures he identified as being essential to success as a stock picker.) This method of constructing portfolios, when allied to good stock picking, is by its nature contrarian. Investors tend to become more bullish as markets go up, and more fearful when they fall, yet the job of the investment counselor is to persuade them to behave in the opposite direction to the one toward which their instincts are pushing them. Although we do not have the detailed records to establish the point conclusively, there is some evidence that this approach generally served clients of Templeton’s investment firm well. The price they had to pay was to lag behind the market during its stronger phases. Given that most investors put a higher value on avoiding losses than they do on making the gains, this is a price that most should be happy to pay.

There are a number of myths and paradoxes about Templeton’s experience as an investor. In his own portfolios, he did not always practice what he later preached. The years of his greatest success with the Templeton Growth Fund only came about because he was unable to sell the fund. His experience in Japanese stocks, although it served him well for a couple of years in the early 1970s, probably did more, ironically, to damage his performance figures than any other single investment decision. His decision to sell out too early was a logical consequence of his methodology, but proved to be disproportionately costly in the late 1980s. Characteristically, this lost opportunity was something that troubled him for several years afterward. His firm was to go through a similar experience in 1999 and 2000, when a three-year period of agonizing underperformance, as the Internet bubble inflated, was only finally vindicated by the subsequent dramatic collapse in the value of those stocks in the TMT sector (telecoms, media, and technology) that had led the market up to its unsustainable highs.

Although his reputation as one of the finest stock pickers of all time is well justified, it did not stop him from making mistakes in the course of his long career. In the 1980s, for example, the Templeton Growth Fund invested heavily in Polly Peck, a London-listed company that subsequently turned out to be worthless and to have overstated its revenues and profits, prompting its founder to flee the country. The way he commiserated with his friend and fellow investor Peter Cundill about their losses in the shares of Cable & Wireless makes it clear that there were many examples of companies that failed to perform as he expected, prompting him to observe that a 60 percent success rate was more than good enough to earn a fund manager the reputation of being a genius.

Despite these disappointments, Templeton remained unwavering in his view that fund managers should not allow business pressures to dictate the way in which they pick their stocks. This conviction was sorely tested during the Japanese and Internet bubbles. When one of the authors asked him for advice after cutting his holdings in emerging markets to zero, a substantial bet against the world market benchmark and what competitors were doing. Templeton replied simply, “I have never thought it sensible to buy expensive stocks for my clients.” That was the end of the matter as far as he was concerned. From direct experience, we can vouch for the fact that he never blamed his analysts for making errors, provided that they had made an honest analytical mistake. The biggest crime, in his view, was not to have the courage to try.

While rightly proud of his reputation as a man who to his knowledge never made an enemy in the course of a long career, and who regarded looking after other people’s money as a sacred trust, John Templeton was not one to allow the commercial value of his gifts as an investor to go to waste. As well as being personally careful with money, even excessively so in some colleagues’ eyes, he showed himself on many occasions to be alive to opportunities to increase the value of his business. Witness for example his advice to colleagues on the need to “indoctrinate” clients of their investment counseling firm about the value of the service they were receiving; or his advice to Mark Holowesko on the need for a fund management firm to launch multiple funds so that at any point in time there would always be one that was showing a strong performance.3

His greatest failing as a businessman was his inability over many years to maximize the commercial value of his skills as a fund manager. The first 20 years of the Templeton Growth Fund’s history were, in retrospect, a long catalogue of missed opportunities. Its later success, once the marketing of the business was placed in the hands of John Galbraith, was equally nothing less than extraordinary. Without it the scale of Templeton’s philanthropy would never have achieved anything like the levels it did. The fact that the fund was able to persist with exceptionally high front-end charges for so many years is a tribute not just to the fund’s exceptional performance, but also to the dominance that marketing continues to play in the way that fund flows are directed.

John Templeton’s principal innovation as a stock picker was to insist on factoring forward earnings projections into the analytical task. This was something that he himself seemed able to do intuitively, working from published data and his own experience and observations of the world. His genius was to be able to reduce complex analytical issues to a set of simple heuristics that not only worked, but could be communicated effectively to others, both inside and outside his own firm. This discipline was rooted in a deep understanding of financial history and human behavior. His ability to focus unwaveringly on the right questions that investors need to address remains a powerful example to investors everywhere.

John Templeton was an optimist by nature and retained an inveterate faith in the capacity of humankind to confront and surmount its problems. This theme runs through all his public speeches and his many books. Not for nothing was “Be Positive” the final of the 16 maxims discussed in Chapter 4. In The Templeton Plan, a primer on how human beings can find happiness, published in 1987, he declared “everything yields to diligence,” and quoted, with approval, a saying of the evangelist Charles Fillimore: “There is no other spot in the universe where man has mastery. The dominion that is yours by divine right is over your own thoughts.” It was a philosophy of life that was to guide his actions throughout his long career in investment. People who pursue the positive, he once noted, get results “whereas those who are cursing the evil usually don’t get far.”

There is no doubt, however, that in the last five years of his life he had become concerned about the consequences of the massive build-up of debt in the developed world. In an unfinished memo, drafted in June 2005, entitled simply “Financial Chaos,” he laid out some of his worries. “Increasingly often, people ask my opinion on what is likely to happen financially,” the memo begins. “I am now thinking that the dangers are more numerous and larger than ever before in my life time. Quite likely, in the early months of 2005, the peak of prosperity is behind us.” After this bleak opening, he went on: “In the past century, protection could be obtained by keeping your net worth in cash or government bonds. Now, the surplus capacities are so great, that most currencies and bonds are likely to continue losing their purchasing power. Mortgages and other forms of debts are over tenfold greater now than ever before 1970, which can cause manifold increases in bankruptcy auctions.”

Turning to the outlook for the corporate and personal sector, he wrote: “Surplus capacity, which leads to intense competition, has already shown devastating effects on companies who operate airlines and is now beginning to show in companies in ocean shipping and other activities. Also, the present surpluses of cash and liquid assets have pushed yields on bonds and mortgages almost to zero when adjusted for higher cost of living. Clearly, major corrections are likely in the next few years.” Further on he adds: “Increasing freedom of competition is likely to cause most established institutions to disappear within the next 50 years, especially in nations where there are limits on free competition. Accelerating competition is likely to cause profit margins to continue to decrease and even become negative in various industries. Over tenfold more persons hopelessly indebted leads to multiplying bankruptcies not only for them but for many businesses that extend credit without collateral. Voters are likely to enact rescue subsidies, which transfer the debts to governments, such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.” He also foresaw a continuation of growing inequality: “With almost 100 independent nations on earth and rapid advancements in communication, the top 1 percent of people are likely to progress more rapidly that the others. Such top 1 percent may consist of those who are multimillionaires and also, those who are innovators and also, those with top intellectual abilities. Comparisons show that prosperity flows towards those nations having the most freedom of competition.”

Despite these concerns, which he was also expressing in private, the conclusion of this memo, arguably the most downbeat he had ever written, was both familiar and reassuring: “Not yet,” he concluded in its final paragraph, “have I found any better method to prosper during the future financial chaos, which is likely to last many years, than to keep your net worth in shares of those corporations that have proven to have the widest profit margins and the most rapidly increasing profits. Earning power is likely to continue to be valuable, especially if diversified among many nations.”

Since his death many of these fears have been borne out by events. Much of the private sector debt that precipitated the global financial crisis has been, in effect, transferred to or taken over by governments. Inflation has started to rise, stimulated in part by governments’ efforts to stave off a more severe economic downturn through the use of unprecedented amounts of monetary stimulus. This in turn has led to an intensifying sovereign debt crisis in the United States and Europe and further declines in the purchasing power of cash and government bonds, the traditional safe havens mentioned by Templeton in his memo. In many developed countries, as he correctly foresaw, real (after-inflation) yields on bonds and cash had fallen so low by the summer of 2011 that they offered savers little or no protection against loss of purchasing power. The real yields on U.S. Treasuries, for all but the longest dated issues, have in fact become negative for the first time in many years.

This is in stark contrast to the situation at the start of this century, when, with equities clearly overvalued, the potential for bonds to deliver superior returns was evident to the smartest investors. John Templeton made a good deal of money for his own accounts in 2000 by a twin-track strategy of shorting shares in Internet stocks and making a leveraged bet on long-dated U.S. government bonds, which he expected to rise sharply in price as interest rates continued to fall. That profitable trade is no longer available. In fact, the decline in yields on government bonds has now run so far in the United States and many other developed countries that they offer a dangerous mix of poor value and high risk. The bonds of leading emerging market countries, most of which have avoided the trap of excessive debt, continue to look like a more attractive prospect.

Many countries around the world are meanwhile engaged in an intensifying currency war, aiming to devalue more quickly than their competitors. Slowing economic growth and sovereign debt worries, coupled with the continued imbalances between the developed and developing world, prompted the International Monetary Fund to warn in late 2011 that the risk of financial instability was greater than at any time since the onset of the global credit crisis, and by extension for many years before that. Inequality, the gap between the rich and the poor, has also risen significantly since the turn of the twenty-first century, to reach levels last seen in the 1930s. In contrast, however, the corporate sector remains in aggregate in rude financial health, with profit margins and balance sheets that are very strong by historical standards.

How, then, do we think that John Templeton would present his take on events, were he still alive today? What are the prospects for investors at the autumn of 2011, when this book is being completed? Is his investment philosophy still valid in these present conditions? These are the topics to which we turn in the final section of the book.

The autumn of 2011 has been characterized by violent swings in stock markets. The financial press has gorged on doom-laden predictions about future growth prospects, political instability, and the risk of potential default on sovereign bonds of many European nations. The United States is still the most powerful military power in the world, but its sluggish economy, combined with political gridlock in Congress, has seen the country lose its AAA credit rating. In August 2011 the federal government suffered the embarrassment of nearly running out of money after a bipartisan stalemate delayed an extension of its borrowing capacity. The fear of a self–reinforcing cycle of financial collapse has been stalking markets and producing ever increasing column inches on how economic Armageddon might unfold.

Before rushing to the conclusion that this outcome is inevitable, it is worth examining the wider and longer context, which we believe is by no means as dark as it might at first appear. Consider first the concerns about the lack of long-term savings in the West and the inability of both corporate and state pension schemes to fund the future retirement of the working population. How did this happen? Many companies failed to top up their in-house schemes when times were good and many governments simply ignored the problem, hoping it would somehow go away. Perhaps the single most important factor, however, has been the improvement in mortality rates. People are living much longer than before, something that in other times would have been heralded as a sign of progress. We have, bizarrely, somehow turned the fact that we all tend to live longer into a negative.

Another burden that exercises many observers is the rising cost of health care. How can we afford to fund the shortfall in future expected costs? It is a valid question, but a more positive interpretation would be that we now have the good fortune to be healthier than we were only a few years ago. That is not an unreasonable ambition for the human race and one, you might think, that might be worthy of some celebration. As well as living longer, we also enjoy much greater access than ever to the store of human knowledge. The Internet, electronic books, and mobile broadband are not just toys to be played with. They are helping to transform the productive capability of the world. The cost of accessing information has become negligible. By eliminating the costs of print and distribution, electronic books now have the potential to make the world’s store of information available to hundreds of millions more people, and at negligible cost.

Over time this has to be a powerful counterforce against rising inequality. The Internet and advances in mobile telephony hold out the prospect that in the world of the future geography and the accident of where you are born will no longer be such a constraining factor as it has been in the past. The next generation of mobile telephony will be as important a communication breakthrough for some communities as the advent of the telegraph was for those growing up in the latter years of the nineteenth century. In developing nations mobile broadband technology will allow instant access to the Internet and all that brings, without the need for heavy investment in underground cables. For the first time rural communities in developed countries will be on an equal footing with big cities in terms of communication resources.

The spread of education and literacy is continuing its rapid advance in the most populous nations of the world. In the last 25 years China has conclusively re-emerged into the family of nations. While the pace of China’s development over the quarter of a century has been breathtaking, it is still in its infancy. Until now China has prospered because of the work ethic of its people, but its recent rapid catch-up in technological expertise will in due course engender a new wave of innovation. Far from being a threat to the world, this can only be a bonus. And while the United States will not easily be supplanted as the center for technological development, increasing contributions from China and India can only add to global prosperity. The strategic goals of the Chinese government now include cleaner energy, reduced pollution, and better health benefits and security of employment. With such formidable political resources officially targeting these objectives, it is likely that they will produce higher living standards and, in time, a necessary shift in the structure of the Chinese economy toward a more consumer-oriented society.

Improved productivity is the key to greater global prosperity, and better health and education are important components in obtaining that objective. They are one of many grounds for cautious optimism that you won’t read about in the media at this time. Readers who are interested in a corrective to the diet of gloom should turn for balance to well argued books such as Matt Ridley’s The Rational Optimist (Harper Collins, 2010). Pessimists, of course, will revert back to the problems of the financial sector and a steady succession of scandals and fraud. John Templeton rightly pointed out that abusing weights and measures is a breach of trust by government, and there is no doubt that many institutions have lost the trust of their constituents. The optimist will note, though, that the market is now clearly penalizing those for whom trust has become a scarce commodity. In many countries today we can see signs of a reaction against those, such as bankers, legislators, and bureaucrats, who have abused their position. Financial institutions that trumpeted profits that they were later forced to concede were no more than accounting sleight of hand now sit under a cloud. They will continue to do so until investors have confidence that their trust is no longer being betrayed. Governments, meanwhile, are slowly but surely losing their gold-plated credit ratings as unfunded spending commitments come home to roost.

Political developments globally, it is even possible to argue, are also starting to move in a more favorable direction. Politicians are losing the ability to buy off voters with promises that their countries cannot afford. Voters in the Western democracies are discovering that the days of living on credit are over. The political classes have been slow to recognize this, but the day when they have to acknowledge this new reality cannot be delayed indefinitely. No doubt there will be continued efforts to maintain the deception that debt can be accumulated without cost. However, many of the developed nations have exhausted the store of wealth built up over many decades and can no longer in aggregate spend more than they earn. The focus will therefore shift away from consumption to earning and saving. As a result, the coming decades are likely to witness a renaissance in the productive and manufacturing industries of the West.

John Templeton would not have succumbed to the Western-centric bias of much comment about current developments in the world. The so-called BRIC countries (Brazil, Russia, India, and China) are experiencing a mirror image of the developments in the leaders of the developed world. In these countries a strictly mercantilist view of the world, built around export-led growth and a culture of domestic savings, will gradually give way to more balanced economies. Just as the West has exhausted its store of wealth and is only now beginning to realize that it can no longer consume more than it earns, so the East is waking up to the fact that it is richer than it realized. The capital that the BRIC countries are accumulating will have to be recycled, just as happened after the Industrial Revolution. Chinese and Indian multinationals will emerge to rival the industrial giants in the United States and Europe. The release of pent up demand in these nations and the innovation that will accompany their emergence can only assist the growth of the productive potential of the world economy.

The year 2011 was marked by political conflict in North Africa and the Middle East. If anyone 10 years ago had dared to predict the popular movements that have swept away dictators in Libya, Tunisia, and Egypt, they would have been regarded as dangerous optimists. It is characteristic of today’s sober frame of mind that now that this has happened, instead of rejoicing many people in the West are too busy worrying about the potentially negative consequences. It is evident that the way forward for these countries is uncertain, but seeing democracy advance rather than retreat was always for John Templeton a positive rather than a negative development. There are many dangers facing the world and big challenges facing policymakers and investors, but there is nothing inherently new in that. It was ever thus; the founder of the Templeton Growth Fund lived under the permanent shadow of a nuclear war for nearly 40 years, yet this did not prevent him believing in the capacity of the human race to grow and prosper. The lesson to be drawn from his life and career is that investors should not lose sight of the resilience of the global economy and mankind’s capacity for progress.

As is always the case in hard times, the question to be answered by investors is how much negativity is already being discounted in the price of shares, bonds, and other financial instruments. Combining a positive frame of mind with the perspective of overall valuations, we would argue that, at the time of this writing, there are more reasons to be optimistic than at first appear. For committed long-term investors, stock markets are no longer discounting unrealistic growth expectations. In fact, it is probable that they will be the best performing asset class for the foreseeable future. In an environment where we can expect global growth, after inflation, to run at the rate of 2 to 3 percent per annum, it is not unreasonable to expect that 10 years from now the S&P 500 index could reach 2,200.

That would represent an approximate doubling from the current level, which is 1,131 at the time of this writing. Yet at that level, it would still not be standing on a cyclically adjusted valuation that is high by historical standards. We have added similar target figures for three other markets, the United Kingdom, Germany, and Japan. Needless to say, these are intended to be the central estimate in a likely range of outcomes, not precise predictions. John Templeton was never foolish enough to say that his statements about future market levels were cast in stone, and we do not wish to make that mistake either. We do, however, think that these are landmarks that are capable of being reached in the next 10 years. See 6.1.

Table 6.1 Forecast Levels

Source: Edinburgh Partners, October 1, 2011.

| Index | 2011 Level | 2021 Forecast Level |

| U.S.: S&P Composite | 1,100 | 2,200 |

| U.K. FTSE 100 | 5,300 | 11,000 |

| Japan: Topix | 740 | 1,600 |

| Germany: Dax | 5,700 | 12,000 |

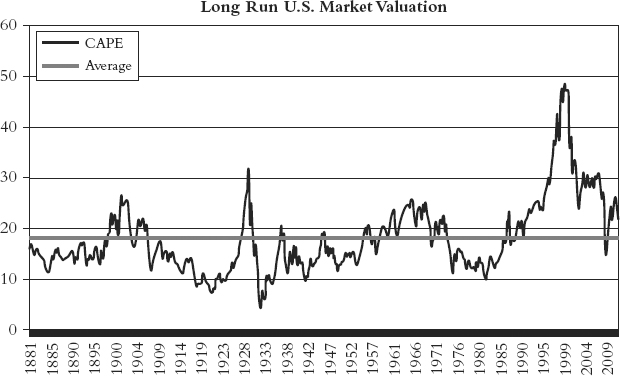

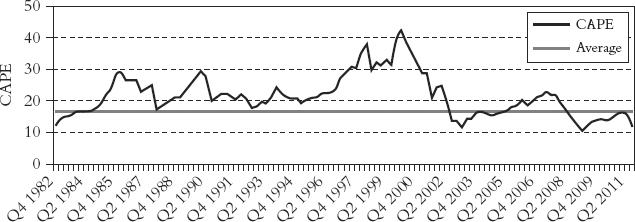

How did we arrive at these figures? We did so by applying the methodology that John Templeton developed. We have combined a plausible further valuation range for the market with conservative growth and inflation estimates, and then translated them into targets that are consistent with these numbers, as well as with historical experience. Presented in Figure 6.1 is the cyclically adjusted price to earnings ratio of the U.S. stock market, using data that goes all the way back to 1871. It is cyclically adjusted in the sense that the earnings component of the ratio is not the current figure, but the current figure divided by the average figure for the previous 10 years. This is a technique adopted by market analysts in order to eliminate the distorting effect on company profits of short-term movements in the economic cycle.4

Figure 6.1 Cyclically Adjusted PE Ratio, United States, 1871 to 2011

Edinburgh Partners from Thomson Reuters Datastream.

The first thing that leaps out from the chart for the United States is how exceptional a period for investors the 1990s were, when set against historical experience. That decade witnessed both the culmination of the greatest bull market in equities in recorded history and a strong performance by bonds as interest rates and inflation expectations fell around the world. The rating applied to the stock market soared in response to abundant liquidity and the re-emergence of China and other emerging markets as a force in the global economy. This golden period for stocks could not be sustained indefinitely, and since the turn of the century, the trend has gone into reverse. The de-rating of equities accounts for a substantial proportion of the poor returns that this asset class has witnessed in recent years. Company earnings have not fallen significantly over the past decade. It is the multiple that investors have been prepared to pay for those earnings that has come down so dramatically. See Figure 6.1.

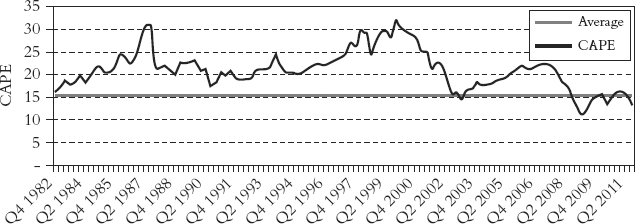

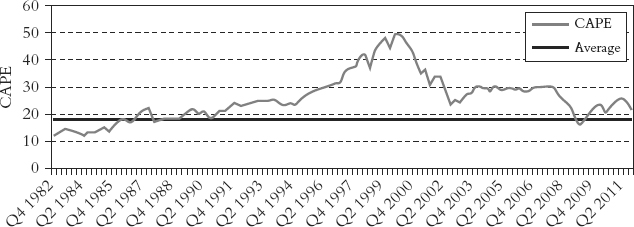

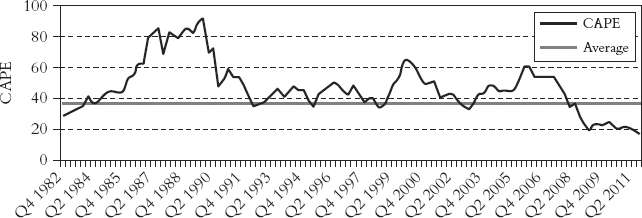

Clearly that process may not yet have run its full course. However, we are now at a point in the global cycle where the valuation of many developed markets has fallen far enough to mean it is now close to the long-term average, based on the cyclically adjusted price to earnings ratio. The same is true for the U.K., Japanese, and German stock markets. While the data series for these countries do not cover as long a period as that for the United States, the long-term average is consistent with longer run U.S. experience. The other markets did not reach quite such high valuations in the 1990s, but the trend since then has been broadly similar. They too are no longer so obviously overvalued as they once were. In fact, on some counts they look more attractive than the U.S. market. See Figures 6.3, 6.4, 6.5, and 6.6.

Figure 6.2 Cyclically Adjusted P/E Ratio, United Kingdom, 1982 to 2011

Edinburgh Partners from Thomson Reuters Datastream.

Figure 6.3 Cyclically Adjusted P/E Ratio, United States 1982 to 2011

Source: Edinburgh Partners from Thomson Reuters Datastream.

Figure 6.4 Cyclically Adjusted P/E Ratio, Japan 1982 to 2011

Source: Edinburgh Partners from Thomson Reuters Datastream.

Figure 6.5 Cyclically Adjusted P/E Ratio, Germany 1982 to 2011

Source: Edinburgh Partners from Thomson Reuters Datastream.

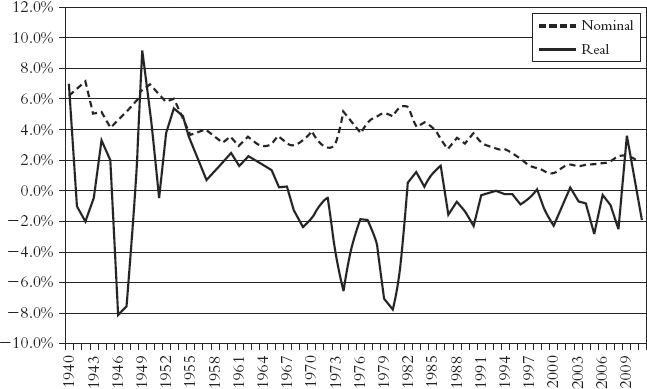

Figure 6.6 U.S. Stock Market Real and Nominal Equity Yield, 1940 to 2011

Source: Edinburgh Partners, Barclays Equity Gilt Study 2011, Thomson Reuters Datastream, Global Financial Database.

The important implication of this is that it is likely that equity market returns will be driven as much in the future by earnings growth as by further changes in valuation. That in turn implies that while future returns from equities will not match those on offer when markets were very low by historical standards, they should offer positive returns in both real and nominal terms. There is a well established inverse correlation between the cyclically adjusted P/E ratio and subsequent real (inflation-adjusted) returns from equities. The higher the adjusted P/E ratio, the lower in general the subsequent return, and vice versa. Could they still get cheaper than they are now? Yes, certainly they can. Share prices can always fall further and faster than basic valuation measures suggest. The issue, however, as John Templeton always saw it, was how the rational investor should respond to the evidence of over or under valuation in the markets.

His years of experience led him to argue for a simple, measured response. In his view, when shares were expensive, it was inherently dangerous to hold on to them all in the hope of finding a “greater fool” to buy them later on. Equally, when they did offer good value it was foolish not to invest in companies on the grounds that they might, conceivably, be available to buy at lower prices at a later date. The risks of being wrong, in either case, were simply too great to justify such behavior. History, according to his research, provides no empirical support for failing to buy equities when they are cheap, however unappealing conditions at the time might appear to be.

Adapting the Yale method, current valuations might suggest that it looks risky to make much beyond a “normal” allocation to equities. While not unreasonably valued, they are certainly far from being dirt cheap. There is another dimension to consider, though. Sir John invariably stressed the need to focus on real, not nominal, returns when considering alternatives in investment. The effect of inflation on wealth is pernicious, and inflation remains a potent longer-term threat in today’s global environment. In their efforts to stave off the impact of the credit crisis, governments in developed countries have slashed interest rates and resorted to wholesale printing of money and other forms of loose monetary policy. This is not only inherently inflationary, but has also helped to distort investors’ perception of risk.

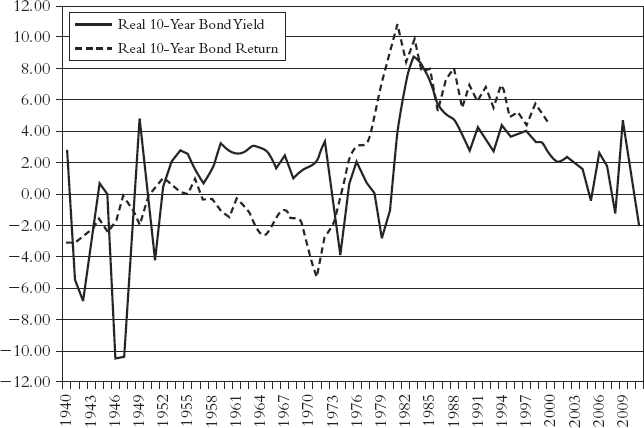

What this means is that cash and government bonds are no longer the safe alternatives they traditionally were. Interest rates on savings accounts and money market funds have dwindled to almost nothing, offering little if any protection against inflation. Government bonds in countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom, in many cases, also offer negative real rates of return, because their yields are below the rate of inflation in the issuing country. Each and every year, in other words, investors who buy bonds at these prices can expect the purchasing power of their investment to diminish. If you share Templeton’s view of the importance of governments maintaining the integrity of a country’s weights and measures, the willingness of many countries to debase their currencies and the value of their bonds is a disturbing development. Only a dramatic fall in future inflation will justify investors buying U.S. or U.K. government bonds at 2011 yields and hoping to make a real return over anything but the shortest of time horizons. The best indicator of future bond returns is the real (after inflation) yield. This is now negative, and that historically has not been consistent with anything other than losing money over time.

Figure 6.7 Real 10-Year Bond Yields and Returns

Source: Edinburgh Partners, Barclays Equity Gilt Study 2011.

Although some ultra-gloomy investors appear to think that an extended period of deflation now lies ahead, historical experience provides little comfort for this view. For the best part of 40 years, between 1940 and 1980, buying U.S. government bonds was an almost sure-fire way for savers to lose the purchasing power of their money. It was only after inflation peaked in the late 1970s that bonds once more began to offer positive real returns. This trend was supported by tight monetary conditions, deregulation, and government policies designed to encourage enterprise and growth. These policies are the exact opposite of those now being followed by Western governments in the aftermath of the global credit crisis. In the 1980s those policies helped to usher in a golden era for bond investors. Inflation fell from 15 percent to less than 5 percent and the resulting fall in bond yields sent bond prices soaring. With real yields on government bonds now in negative territory, the opportunity for a repeat of this experience no longer exists. The risk is all on the other, inflationary side of the equation.

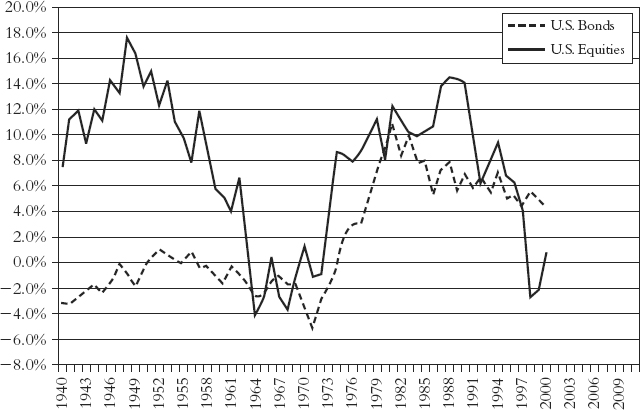

Figure 6.8 shows the 10-year annualized real returns that have been obtained by investing in both U.S. equities and U.S. government bonds over the past 70 years. The realized returns are plotted against the starting date of each 10-year period. So, for example, someone who invested in equities in the late 1990s would have obtained a negative real return 10 years later. (The heavy plotted line falls below the 0.0% horizontal gridline.) In contrast, for someone who invested in U.S. 10-year bonds, shown by the dashed line, the annualized real return over the next 10 years would have been somewhere above 4 percent per annum. The critical point, one that John Templeton emphasized at all times, but which many investors appear to forget, is that a realistic target return from either equities or bonds is heavily dependent on their respective valuations at the point of investment. We obviously do not know what the actual realized returns from an investment made in 2011 will turn out to be, but it is long odds on, given their respective valuations, that equities will produce a higher 10-year return than U.S. government bonds. The former are relatively cheap and the latter both relatively and absolutely expensive.

Figure 6.8 Comparable Real Returns, U.S. Bonds and Equities (annualized % per annum from start date)

Source: Edinburgh Partners.

The historical experience with equities is not so discouraging. Certainly there have been many periods when returns from equities were poor. The last decade has been one of them. Since 2000 investors in bonds have continued to make positive real returns while the real returns from developed market equities have slumped. (Equities in many emerging markets have delivered much higher returns, however, underlining the way that economic power has shifted from West to East, a trend that John Templeton was one of the first to identify.) This experience helps to explain why investors have such a negative view on equities as an asset class. It was also what John Templeton himself anticipated with the shifts in his own portfolios at the start of the decade, buying government bonds. Equities have been poor on both an absolute basis and relative to bonds. The explanation is readily apparent from the cyclically adjusted P/E graphs. Although the returns of the 1980s were repeated in the 1990s, they were not underpinned by sustainable growth in earnings, as they had been in the previous decade. Instead market valuations simply rose to a level from which they were bound to decline, and that decline outweighed any earnings growth. Today, however, the cyclically adjusted earnings ratio no longer sits at such elevated levels and has fallen back, closer to the long-term historic average. As such it is reasonable to expect that returns from here on will also fall within their historical ranges.

So, while equities, particularly in the United States, are not obviously cheap, they do have the advantage that they can offer what the traditional safe havens no longer can, which is protection against the loss of wealth. If we assume that global growth remains relatively anemic for a few years, but that inflation averages approximately 3 percent per annum (which may well prove to be an underestimate), then it is reasonable to expect that the major stock market indexes will double in nominal terms over the next 10 years. Adjusted for inflation, this would equate to a real return of approximately 4 percent per annum. While this is lower than the long run historic return on equities, which is around 7 percent per annum, it nevertheless does hold out the prospect of an above-inflation increase in wealth. On almost any scenario, barring only a rerun of the Great Depression, the 10-year return from equities is likely therefore to be well above the return available on U.S. government bonds. The average real loss from owning bonds over 10-year periods between 1940 and 1980 was well over 10 percent, and in some periods two or three times that level. Investors eventually caught on to the fact that they needed to earn a positive real interest rate as a reward for holding government securities.

Those investors today who feel safe with government bonds will in due course come to realize that this feeling is misplaced. Much greater safety over the next 10 years is likely to be found in equities, given today’s relative valuations. The key, as the subject of this book repeatedly pointed out, is to remember that investment in equities is an investment in the future growth of the world and that as long as one does not pay too much for them one can expect to be rewarded over time. We have no doubt that equities would be John Templeton’s preferred asset class in today’s environment, as indeed he suggested at the end of his memo on financial chaos that we quoted earlier. Progressively buying when stocks become cheap and progressively selling when they become expensive is what John Templeton did. It worked for him—and it can work for those who have outlived him.

Despite the gloom that settled on investors in the course of 2011, the outlook for equity returns, while hardly the greatest bargain they have ever been, has improved. The economic Armageddon being predicted by some is not the most likely outcome. More likely is that policymakers in Europe and the United States will, to paraphrase Winston Churchill’s view, arrive at the right answer, but only after exhausting all the alternatives first. The fact that investor confidence is so low at the time of writing is an additional source of comfort. If he were with us today, we believe that John Templeton would point out that the gloom in financial markets now offers grounds for optimism. As he repeatedly said, the best time to invest is always at the time of maximum pessimism, and we appear to be closing in on that point in this market cycle.

Notes

1. The phenomenon of increasing short-termism in modern financial markets has been highlighted in a number of recent authoritative studies by authors such as Alfred Rappaport and Jack Bogle.

2. The popular writer Malcolm Gladwell elaborates on this idea in his book Outliers, in which he argues that thousands of hours of practice are the key to the success of those who reach the pinnacles of their chosen sport or profession.

3. Reprinted in the Appendix.

4. To be precise, the data for the chart is arrived at by dividing the latest monthly figure by the trailing 10-year moving average of the same series.