The invention of the steam engine turned the agricultural society – the „Economy 1.0“ – into an industrial society – the „Economy 2.0“. Later, the spread of education enabled the service society – the „Economy 3.0“. Nowadays, the pervasiveness of digital technologies is driving another technological revolution, which is creating the „Economy 4.0“, which I call the Participatory Market Society. This society is characterized by the ubiquity of information, bottom-up participation, „co-creation“, self-organization and collective intelligence as new organizational principles. We will also see more personalized products and services and an increased engagement in a serious and fair partnership with citizens, users, and customers. Finally, the spread of „projects“, empowered by social collaboration platforms, will enable more flexible and efficient forms of production and services.

Our economy is in the middle of a once-in-a-century transformation. Big Data, Artificial Intelligence, and the Internet of Things will fundamentally change many of our current procedures and transform the institutions on which our economies and societies are based.

The invention of the steam engine was a crucial technological catalyst in the transition from the agricultural society (“Economy 1.0”) to the industrial society (“Economy 2.0”). This new industrial society was driven from the bottom-up by entrepreneurs, whose self-interested “rational” mindset is often reflected by the theoretical concept of the “homo economicus”. Consequently, very little attention was paid to social and environmental “externalities” such as mass unemployment, poverty, malnutrition, child labor, pollution, and the exploitation of resources.

In response, many countries established health insurances, social security systems, and environmental laws. By increasingly complicated regulations, new jobs were created. A new service sector (the “Economy 3.0”) was grown. Affordable mass education played a key role in creating the societal conditions in which this shift could take place. In service societies, administrations based on top-down planning and optimization became the new organizational basis. Now, driven by the digital revolution, a new kind of economy (“Economy 4.0”) is on the rise. How will it look like?

10.1 We Can, We Must Re-Invent Everything

Nowadays, however, the world is often too complex for timely or proactive top-down governance. In particular, neither governments nor multi-national companies have so far been able to overcome complex problems such as climate change, overfishing, unsustainable use of resources, international conflicts, and global financial instability. Moreover, the problems of overregulation and high government debts are basically unsolved. Conventional modes of governance, which are based on standardized procedures, are also not very good at satisfying diverse local needs.

Therefore, the creation of new institutions and approaches is inevitable. In particular, we need information platforms which can harness the diverse knowledge in our society and support more effective decision-making. Before I describe how I think the Economy 4.0 will work, I would like to provide a quick overview of the transformation which is already underway. This will help to illustrate the fundamental changes to our socio-economic systems that we should expect. Indeed, these changes will be of a magnitude greater than anything we have witnessed in the last hundred years.1

10.2 Personalized Education

In the past, the academic system did a remarkable job in compressing increasing quantities of knowledge into surprisingly few lectures. Often, centuries of knowledge were squeezed into a single course. However, our world is now changing faster than ever. We are probably in a situation where most of our personal knowledge is already outdated and where it is impossible to follow all of the news that might be relevant to us. Even scientists and doctors are struggling to cope with the exponential increase in knowledge. Politicians and business leaders are confronted with similar problems, too.

In response to this challenge, the education system has already started to change. We are now seeing an explosion of new bachelor and master degrees, which go beyond the classical fields of study such as mathematics, physics, chemistry, biology and history. This increasing diversity means that people can now find study directions which better fit their interests and talents. Moreover, massive open online courses (MOOCS) are quickly spreading through platforms such as Coursera, Khan Academy, edX or Udacity, which enable people to learn about almost any subject from some of the best professors in the world. Such virtual courses are often taken by huge numbers of visitors. Up-to-date, high-quality knowledge can now be shared with millions of people, who can learn a subject whenever they want.

The next step in the evolution of personalized education might be the use of particular multi-player, interactive online games. This would allow participants to explore the laws of nature, to experience different historical ages or cultures, and to interact with fellow students. Professors may act as coaches or “chatroom masters”, providing guidance, correcting misunderstandings and answering questions that cannot be readily addressed with knowledge from the Internet. Furthermore, virtual, three-dimensional video meetings may become standard, once the necessary technology and bandwidth are in place.2

Of course, schools must change dramatically as well. Teachers complain about burnout, aggression in the classroom, and worsening test results. Are schools still preparing children well enough for a successful future? Pupils complain that the knowledge they learn is outdated and not very useful to them. They feel that the Internet now provides faster and more accurate answers than their teachers. It might be true that pupils are losing the ability to memorize facts and focus, and that they are over-stimulated. But they certainly want to learn things that fit their personal interests and needs. Unfortunately, the standardization inherent in today’s education systems inhibits the motivation and creativity of many pupils.

In future we will need less standardized education but more personalized learning focused on imagination, creativity, innovation, and collaboration. Rather than presenting children with a predetermined curriculum of things that they “should know”, greater emphasis must be placed on the ability to learn individually and in teams. This would involve teaching pupils where they can find reliable information, and how they can critically assess it and use it responsibly. Rather than forcing children to put their smartphones and tablets aside, we must reach out to them on their own territory—the Internet. We need to help them to use information technology to develop their ideas and successfully engage with others.

In conclusion, the schools of today belong to a bygone era. They are the manifestation of an outdated concept of education which is no longer fit for purpose. Drumming standardized knowledge into pupils’ heads simply doesn’t work anymore. Education must become an exercise in systematically exploring the wider world and critically assessing information.

10.3 Science and Health, Fueled by Big Data

We are also at the beginning of a dramatic change in the way we analyze scientific data and manage our health systems. Although I disagree with Chris Anderson, who posits that Big Data will bring about the “end of theory”, I do believe that it has the potential to change research methods and scientific disciplines. Traditionally, we have had three pillars of knowledge creation, namely theoretical analyses, experiments, and computer simulations. But the analysis of Big Data now provides a fourth pillar.

Big Data is not an oracle which will answer all the world’s questions, but the availability of huge data sets will empower us to gain insights in a way that was impossible before. The analysis of Big Data helps us to find initial evidence quickly, even though the correlations and patterns discovered by this kind of analysis will often not imply reliable conclusions. Nevertheless, if combined with good theory, computer simulations, and/or targeted experiments to verify or falsify certain hypotheses, Big Data can help us to generate better knowledge faster and more effectively than ever before. For this reason, Big Data will certainly transform research and innovation.

The health system is another institution which will benefit a lot from Big Data. For example, IBM’s Watson computer will soon support doctors in diagnosing and treating diseases by evaluating a much larger body of medical literature and evidence than doctors could do on their own. In addition, it will become possible to correlate our health status (or diseases) with our diet, genetic predisposition, and data about our socio-economic environment. Rather than having to undergo general medical treatments with considerable side effects, as was the case with antibiotics and other medication in the past, the health systems of the future will enable personalized medicine and treatments which will be designed and calibrated to meet the needs of individuals. These treatments will be more effective while reducing undesirable side effects: what is good for one person might be bad for someone else. Furthermore, we might be able to diagnose emerging diseases early on, before they break out, thereby helping us to prevent them. As a result, disease prevention might become more important than treatment. Obviously, this will cause a major paradigm shift in the health system.

A further interesting opportunity is opened up by a recent study conducted by Olivia Woolley Meza, Dirk Brockmann and myself.3 To fight pandemics, it is important to immunize people in order to reduce the spread of an infection from one person to another. But how can we ensure that a sufficient number of people gets immunized (particularly when supply is limited)? Immunizing everyone is typically not possible because there are usually not enough immunization doses. Informing the public about the infection through mass media is also not effective because many people will either not respond or overreact. Surprisingly, however, if people knew about the number of infections in their social circle, this would let those who are most likely to be infected seek immunization. In other words, local information can be more effective than global information. Information platforms such as Flu Near You or Influenzanet4 are now making this type of local information flow possible.

To benefit from the opportunities mentioned above, we must carefully establish a trustful relationship with the patient. Before sensitive personal and health data can be used, trustworthy and reliable information technologies and governance frameworks need to be developed so that patients have a sufficient level of control over the use of their treatment and data and how this affects their lives. Most likely, the health system can only be sustainably improved, if there is a reasonable involvement of the patients.

10.4 Banking and Finance

The financial sector has been in turmoil since a long time. This is probably best illustrated by the latest financial crisis and by new phenomena such as flash crashes, which can wipe out almost $1 trillion of stock market value in a couple of minutes, as it occurred on May 6, 2010.5 These flash crashes are considered to be a side effect of algorithmic trading. In fact, about 70% of all financial transactions are now autonomously performed by computers, whereby markets are continuously and automatically monitored for potential opportunities. An entirely new financial business model based on high-frequency trading has emerged, which has undermined the foundations of traditional financial investments.

There has also been an explosive expansion of shadow banking and the market of derivatives.6 In many cases, derivatives have replaced insurance contracts. They have entirely transformed the insurance business and the way real estate is financed.7

Furthermore, payment processes and money are also undergoing a transformation. While most financial transactions were based on cash or bank transfers in the past, they are increasingly being replaced by credit card payments and systems such as Paypal, Google Wallet or Apple Pay.

Furthermore, we see a trend towards microcredit, peer-to-peer lending and peer-to-peer money transactions, be it through BitCoin, P-Mesa or other means. Hence, the trend is towards decentralized approaches, where banks are not needed as intermediaries anymore. Monetary transactions are directly executed between people. This may be seen as a response to the failure of banks to provide a good service for everyone, evidenced by the unaffordability of loans and private homes for a broad range of companies and people. Some people even think the latest financial crisis, by far the biggest ever, was a direct result of the digital revolution. This is, because interactions based on trust were replaced by credit default swaps and other financial derivatives, which sought to insure traders against high losses. In the future, banks and other companies will certainly have to pay more attention to trustable products, procedures, and systems to be successful.

10.5 In the Wake of Big Data, the Pillars of Democracies Are Shaking

Democracies are often said to rest on four pillars: the legislative body, the executive body, the judiciary and the media. Personally, I think that science should actually be included as a fifth pillar of democracy. How would one otherwise want to make well-informed decisions? If governments want to fulfill their democratic mandate well, evidence-based decision-making is certainly essential. All of these pillars, however, will soon undergo a fundamental transformation and the signs of change are already there.

We have seen perhaps the most dramatic changes so far in the media. The Internet has undermined the traditional business model of printed newspapers because news is often provided for free in an attempt to attract more readers and online advertisers. A similar dynamic is at play in the music and film business. However, these businesses were the architects of their own downfall: they entered the digital arena before they had developed a viable online business model.

In addition, people are now turning away from mass media in favor of TV on demand and engage with personalized information sources such as tumblr. In this field too, there is clearly a trend towards individualization and decentralization, where people play a more active role in choosing and curating the information they consume. In an internal report on the digital strategy of the New York Times, for example, the paper’s readers were identified as its most “underutilized resource”.8 By writing comments and blogs, and by sharing news stories on social media, readers are reshaping the media landscape. They determine which stories and which news sources reach a wide audience online. Grassroots journalism which builds upon local expertise is another interesting development.9

Beyond the media world, however, the executive branch of governments and the judiciary are also quietly changing. Police, secret services and other authorities now routinely use surveillance and Big Data to identify crime hotspots, terrorist suspects, traffic violations, tax evaders, and corruption. To accelerate trials, plea bargaining is becoming increasingly common. In addition, the judicial process is being shortened, which often means that defendants have fewer opportunities to defend themselves. The international trade agreements currently under negotiation10 even envisage that conflicts of interest will be settled outside of the existing court system. Again, these changes are driven by the desire to increase efficiency by removing regulatory obstacles. Complementary, conflicts of interest may also be resolved through voluntary settlements negotiated in a community-based mediation process.

In the area of administration, many routine jobs will be taken over by computers. I believe it is just a matter of time until the legislative process will undergo a fundamental transformation, too. First, the concept of centralized decision-making is increasingly being questioned by countries and citizens who feel that diversity is not valued highly enough. Second, we have to overcome the problem of over-regulation by adopting new approaches which allow for more innovation and for solutions which are tailored to local needs. Therefore, I believe that long-term planning and administration will increasingly be complemented or replaced by more flexible approaches. I am convinced that the information systems of the future, particularly the Internet of Things, will enable self-organization, (co-)evolution, and collective intelligence. These approaches will probably become the new organizational principles of the digital society and the Economy 4.0 to come.

Instead of trying to control innovation through complicated regulations, it might be better (particularly for job creation) to transfer the responsibility for their externalities (i.e. the positive and negative consequences) to the beneficiaries. The simple rule that the originator of externalities would have to compensate others for damage created might replace thousands of complicated regulations by simple measurement standards and unleash a wellspring of creativity which is currently stifled by red tape.

In fact, over-regulation, too low innovation rates, and unemployment levels are currently among our greatest worries. Recently, there were about 25 million unemployed people in the European Union (the EU-28 states), and close to 20 million in the Eurozone.11 However, this does not even begin to account for the vastly greater number of people who are not officially seeking employment (and thus are not counted as unemployed), while they would actually like to have a job if one were available for them. Unfortunately, things will get even worse as many employees will be replaced by intelligent machines. Experts predict that the number of jobs in the industrial and service sectors will drop by 50% in the next 20 years.12 Unfortunately, large technology companies are unlikely to create enough new employment in the digital sector to make up for the difference. As a consequence, we may see an unemployment rate of 30 to 50% or even more—a number that probably no country can sustain based on the current socio-economic framework. Faced with such challenges, it is clear that we need to reinvent everything—our economy, the way we innovate, the way we do business, and the way we run our societies (see also Appendix 10.1).

10.6 Industry 4.0

Recently, many newspaper columns have been devoted to the rise of the “Industry 4.0”. To explain what this is about, let us begin with the “Industry 1.0”, which represents the first stage of industrial automation, involving innovations such as the steam engine and the mechanical weaving loom. In turn, the “Industry 2.0” was the age of the conveyor belt, which heralded the dawn of mass production. This process was further refined by the “Industry 3.0”, whereby many production tasks were carried out in a computerized way or even by robots. Finally, the “Industry 4.0” marries mechanization with communication technology to make it possible for intelligent machines (or robots) to directly communicate with each other or with the few remaining production workers. The “Industry 4.0” represents the next step of automation, which will eventually lead to a largely self-organizing production system. For example, in modern car factories, there are almost no workers. Most of the tasks are performed by robots, which are remotely controlled by a few skilled engineers.

The key communication technology driving this development is the “Internet of Things”, which uses networked sensors to generate information that can be used to manage production in real-time. At home, the Internet of Things plays a similar role, allowing us to control our Bluetooth stereos or TV sets with our smartphones or tablets. But it would be naive to believe that the only consequences of digital technologies will be more efficient production processes and smarter gadgets. The digital revolution will transform our entire economy, and our societies as well. We will see a trend towards selforganizing systems everywhere. Concepts from complexity science will be empowered by Internet of Things technologies and vice versa. This will provide us with the key to a better future.

10.7 New Avenues in Production, Transportation, and Marketing

Let us now look at disruptive innovations in the areas of business and transportation. For 100 years, vehicles have looked more or less the same. They have had four wheels, a petrol or Diesel engine, a steering wheel and a driver. The production of vehicles was centered around a few companies who could benefit from “economies of scale” and advertise their products to a mass market.13

But now, it has suddenly become fashionable to drive electric vehicles produced by companies such as Tesla, while Google and other firms are developing driverless cars. Furthermore, Uber is challenging the traditional taxi business model by connecting passengers directly with freelance drivers in their vicinity. Amazon is even experimenting with automatic delivery by drones.

Rather than creating catch-all messages for a mass audience, advertisers are increasingly using personal data to deliver tailored messages to specific target markets. The customers don’t anymore have to search for products that might interest them—the products and services find their way directly onto the screens of potential customers. Online shopping platforms know our desires and suggest which book we should read, which product we should buy, and which hotel we should book. Rather than visiting a shop and hunting for a product, as we would have done a few years ago, we now increasingly shop online and get a far greater array of products delivered to our homes than what we can find in a shopping mall.

But that is not all. Companies like eBay allow everyone to sell products. This creates a peer-to-peer market, whereby items can be reused. Rather than throwing a used product away, we can now sell it, donate it, or share it with others. In fact, we are currently witnessing the emergence of a “sharing economy”. Car sharing is just one of the earlier examples for this. Now we enjoy new services such as Couchsurfing or Airbnb, which offer strangers the opportunity to stay as guests in other people’s homes—something that would have been unimaginable just a few years ago (before the emergence of online reputation systems). In the meantime, neighbors share drilling machines and other tools, books and bikes, and offer personalized services.

The emergent sharing economy seems to be the result of the recent economic crisis. While earning less, people try to maintain a high quality of life by sharing goods. As a positive side effect, resources are being used in a more sustainable way. In future, the sharing economy is a great opportunity to further increase living standards despite the competition of a growing world population for the limited resources of our planet. The sharing economy will certainly be an integral and important part of the circular economy, which we need to build in order to reduce scarcities and waste.

The sudden move towards shared use (which may be seen as a special case of “recycling”) is enabled by novel online platforms that can directly match supply and demand at a local level. It is now possible to coordinate the socio-economic activities between many more individuals, even though they might have very diverse interests, skills, resources, and needs. The companies facilitating this coordination enjoy remarkable growth rates of around 20%, which benefits from the recent trend towards sharing rather than exclusively owning goods.

However, we can also see a trend to buy and sell personalized products, for example, tailor-made jeans. In fact, entire shops have been established to customize mass products to individual tastes. Individualized production is becoming a trend. This is fueled, for example, by 3D printers and other new production methods.14 After the “democratization of consumption” in the twentieth century,15 we see a “democratization of production” in the twenty-first century. In fact, the separation between producers and consumers is already eroding. We are becoming a mixture of producers and consumers, so-called “prosumers”, who play an active role in the conception and production of the goods we buy. On the Internet, and even more so on social media, this has already been true for some time.

Eventually, it will not make much sense anymore to manipulate opinions through advertising. Instead, companies will simply give us what we really want, if we are willing to let them know. In the future, a symbiotic relationship between producers and consumers will be key to economic success. Companies that don’t care about the wishes and opinions of their customers will have little chance in the marketplace, while those which engage in a fair partnership with their customers will thrive. Therefore, we will see a shift from a company-centric market to a user-centric market.16 Cooperative networks between consumers and producers will also play an increasingly important role for providing the information that is necessary to create better services and products.

This trend towards more personalized and individually customized products will create a “hyper-variety market”. In fact, the digital economy will open up a vast array of business opportunities and new product categories, as the information age unleashes a wave of creativity. The possibilities to produce creative products such as music, news, blogs, and videos will be endless. The current growth in the market for smartphone apps and virtual goods and services is a harbinger of this potential. For example, every minute, more than 500,000 posts are published on Facebook. Moreover, there are now more than half a million smart phone apps in existence and about as many app developers in Europe. In 2013, Apple alone generated more than $10 billion dollars in revenue for developers through its AppStore. In December 2013, more than three billion apps were downloaded.

This has very interesting implications for the future structure of markets. While today, we have a few monopolies or core businesses and some peripheral business activities, it is likely that peripheral products will become increasingly important in future.17 This doesn’t mean that large companies wouldn’t grow any further. We should rather imagine this transition like a digital desert turning into a digital rain forest, where species of all kinds and sizes coexist.18 This transition will benefit from a number of facts: First, in the emerging “zero marginal cost society”,19 producing copies of a digital service or product is cheap, and creating more copies doesn’t cause much higher costs. Second, it is important to realize that the digital economy isn’t a zero-sum game, where one can only gain when others lose.20 Therefore, besides getting rich by cutting costs and rationalization, where immaterial (information-based and cultural) goods are produced, co-creation and social synergy effects offer a second way of creating value. Third, participatory information platforms can act like “catalysts”. In some sense, they are the “humus” fueling the evolution of a thriving digital information, innovation, production and service ecosystem. Such digital ecosystems enable exponential innovation (rather than producing a new version of a certain product every few years, as we often have it today). To allow this exponential innovation to happen, we need interoperability and suitable intellectual property rights (IPR) (see Appendix 10.1). Even the G8 Open Data report points out that the competitiveness of countries will depend on the sharing and reuse of data.21 This will be crucial, in particular, to avoid mass unemployment by creating opportunities for small and medium-sized companies, and for self-employment, too.

10.8 Where Are We Heading? New Forms of Work

The digital economy will profoundly affect the world of work. In the past, long-term employment at one company was common (at least in large German companies such as Daimler Benz, BMW, or Bosch). In the meantime, however, companies increasingly opt to employ their staff on rolling, short-term contracts. A growing percentage of the workforce already works on a temporary basis, and we will probably see a further rise in short-term employment. Amazon Mechanical Turk, for instance, enables companies to outsource certain tasks to a casually employed workforce, where the “working relationship” between employer and employee often lasts for a few minutes only!22 In this way it is, for example, possible to translate a 1000-page document within minutes, by splitting the task into 1000 subtasks, done by 1000 people.

Such short-term commitments may come at the cost of significant increases in the stress levels of employees. In view of the growing insecurity and existential risk created by these new forms of employment, an increasing number people advocate the introduction of a basic income enabling everyone to survive, even though not very comfortably.23 This is a hotly debated topic: Why should people be entitled to get an unconditional payment? Would the state be able to pay for it? Would people still work hard, or would they get lazy? Probably, even if a basic salary were introduced, our economy and society should continue to build on merit-based principles such that most people would try to increase their incomes through paid work in order to reach a higher quality of life.

10.9 Everyone Can Be an Entrepreneur

Whatever your opinion on the issue of a basic income may be, it’s likely that people will increasingly set up “projects” to earn money with own products and services. Such projects will be task-driven, supported by digital assistants, short-lived, and very flexible.24 The entrepreneurs of the future will launch and coordinate such projects and organize the necessary support, as discussed below. Once completed, a project will end and the workforce will look for new projects to coordinate or participate in. Many people will probably coordinate a project and simultaneously participate in others.

Such a project-based socio-economic organization has a number of advantages. The projects will provide their participants with opportunities to influence the issues they care about. Project participants will also be able to work with a greater degree of independence in fields that genuinely excite them. As the projects will be short-lived, this will further overcome the “Peter principle”, which posits that, in a conventional working environment, employees tend to be promoted until their position is beyond their ability.

Due to the various advantages, companies, political parties and other established institutions will increasingly use the organizational form of projects to complement their existing activities in a flexible manner. This will also help to overcome another crucial problem: many institutions today are too slow to adapt to our quickly changing world in a timely way.

10.10 Prosumers—Co-Producing Consumers

Digital technologies are now enabling entirely new and more flexible ways of organizing our economy and society. People are starting to use social media platforms to organize their own interests and are establishing their own “projects”. In principle, everyone could do this now, given the required technical and social skills. The World Wide Web, social media, and homemade products created with 3D printers are just three examples of this trend. In fact, 3D printing technology is now enabling local producers or individuals to sell products to friends, colleagues and the rest of the world. Rather than merely specifying the color and individual features of a product when we order it, we can now design its components or composition to produce bespoke products, tailored to our needs. It is even possible to set up a team of designers, engineers, marketing professionals, and other specialists to design a customized smartphone with components produced by multiple companies or with new, tailor-made components. Furthermore, conventional factories are increasingly working hand in hand with collaborative projects brought about by the newly emerging digital economy.25

Note that “projects” as I have described them above are already in existence. Open-source software projects, for example, are largely run by people who want to use open-source components to develop own software more quickly, which they then make available to everyone in exchange. Such “open innovation” is typically built on a framework of “viral” open-source licenses, which encourage users to contribute something in return for what they get for free. These software licenses (such as the GNU General Public License) reward a culture of collaborative creation (“co-creation”), reciprocity, and fair sharing.26

This is fueled by the principle of “co-epetition”—a special form of competition that goes along with cooperation. In the context of open-source development, the GitHub platform has become particularly popular among software developers. The platform shows who has contributed what, whereby it creates incentives to contribute. Thus, everyone can benefit from the growing “ecosystem” of open-source software.

We must further pay attention to another fundamental change: as the Internet connects citizens, customers and users, we see a trend towards more bottom-up participation in our socio-economic system. Apparently, it can be counterproductive to engage in too much centralization and standardization without providing sufficiently diverse opportunities for an array of countries, regions, and local communities with widely differing interests, needs, weaknesses and strengths.27 As systems become more complex, it takes more local knowledge to satisfy the increasing diversity of needs, which calls for more participation. Otherwise, complex socio-economic systems will perform poorly or may even become unstable over time. Therefore, let us now discuss the advantages and disadvantages of top-down and bottom-up organization in more detail.

10.11 Top-Down Versus Bottom-Up Organization

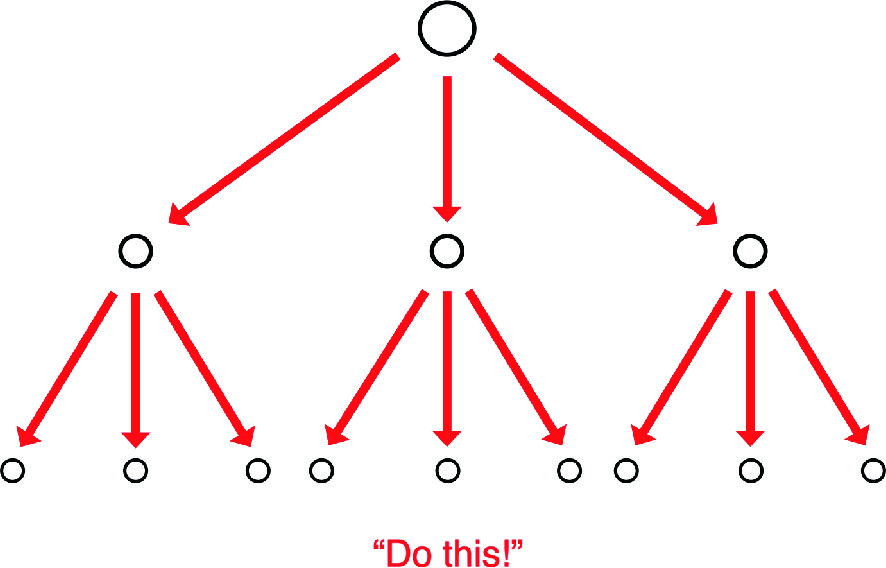

Top-down organization is common in military organizations, administrations, and many companies. The aim of this approach is to “command and control” so that leaders are able to exert their power and get their wishes and decisions implemented. The hierarchy inherent in such systems also makes it easier to establish a system of accountability. Top-down organization, furthermore, enables rapid decision-making and timely coordination of resources over large distances. The collection and evaluation of information required to make decisions, however, is often quite slow, because it takes a long time for information to flow up the chain of command28.

Using a top-down approach, it is possible to reach optimal results in a system, if the goal is well defined and the outcomes can be well determined, i.e. if the system isn’t too complex, if it doesn’t vary much, if changes are reasonably predictable, and if problems can be well detected and quickly solved. Under such conditions, top-down control can increase the performance of a system. Often, however, at least one of these conditions is not fulfilled.

While the top-down approach can harness the individual intelligence and expertise of exceptional leaders, the large accumulation of power implies that incidental mistakes can be disastrous.29 In other words, the centralized leadership structure of top-down systems can help to solve problems, but it often creates new (and sometimes even bigger) problems. Moreover, although top-down control enables faster change, it often delays necessary change.

In sum, a top-down approach might be best if a system is sufficiently simple and deterministic, and its variability is low. Therefore, it benefits from standardization.30 A top-down approach works well in situations where it is more important to be decisive than to wait for consensus. A medical emergency might be a good example. But systems which are controlled from the top-down are vulnerable, and the concentration of power makes them easily corruptible.

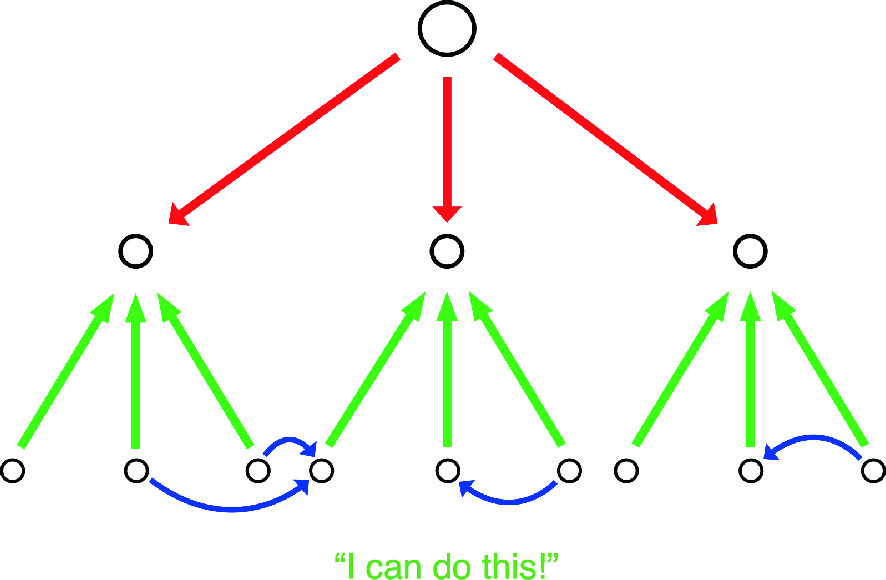

By contrast, bottom-up organization performs better under complex and highly variable conditions, if suitable coordination mechanisms are in place. Good examples are our immune system, markets and ecosystems. Bottom-up organization supports flexibility, local adaptation, diversity, creativity, and exploration. It also tends to be more resilient to disruptive events.

Bottom-up organization fosters democratic processes, but may also cause herding behavior. To work well, good education and a willingness to take responsibility at the bottom is required. Using a decentralized approach, more information can be processed, and collective intelligence is enabled. However, collating and integrating this information to make it useful tends to be challenging.

On the whole, top-down organization is based on the principles of power and control, whereas bottom-up organization empowers people to help themselves and each other. Top-down governance results from the accumulation of resources and asymmetry in the system, while bottom-up governance benefits from distributed control and tools that support peer-to-peer coordination. However, given that top-down and bottom-up approaches both have strengths and weaknesses, neither approach will work best in all situations. In fact, these approaches can complement each other, and both are necessary. They must be applied in the right circumstances or suitably combined.

Currently, Big Data is being used to strengthen the top-down governance of our socio-economic systems, but a number of factors promote the spread of bottom-up organization, too. High levels of education as well as access to reliable, high-quality information and to information systems supporting evidence-based decision-making are important for this trend. In addition, Social Technologies are beginning to foster collaboration and trust in circumstances where it has been lacking before. For example, social media platforms are helping people to coordinate resources, while the growth of reputation systems lets people and companies behave more accountably and responsibly. Bottom-up approaches have further been strengthened by the spread of Open Data, citizen science, moderated Internet communities, and the “maker” movement.31

To cope with the increasing variability and complexity of socio-economic systems, more autonomy at lower organizational levels and distributed control approaches are often necessary. This is fundamentally changing the landscape for policymakers and citizens alike. In fact, more bottom-up participation is required for a number of reasons: there is a need for more capacity (“bandwidth”), more creativity, better solutions, and more resilience. Further advantages of bottom-up participation are related to diversity (such as innovation and collective intelligence), but we must certainly learn to master the challenges of diversity better. For this, we need suitable information systems, which support a differentiated kind of interoperability. Digital assistants and new kinds of Social Technologies (as I have discussed them in previous chapters) are examples of such information systems.

For all of the above reasons, decentralized, bottom-up organization is currently spreading. The rise of BitCoin and peer-to-peer lending may be taken as examples. Moreover, using smart grids, electricity can now be (co-)produced by citizens. “Swarm intelligence” is another powerful, decentralized approach inspired by the self-organized behavior of socially behaving animals. Taking this principle several steps further, citizen science and crowd sourcing have given rise to a number of credible information platforms and community services. Here, I have not just Wikipedia and OpenStreetMap in mind. In California, for example, citizens are collectively detecting earthquakes using a distributed network of sensors,32 while in Japan a crowd-based sensing system has been developed to monitor nuclear radiation.33

10.12 Allowing Diverse Resources to Come Together Quickly

Let us now explore how modern information systems can allow top-down and bottom-up organization to come together in order to create new and superior forms of organization. In this context, it is instructive to examine the example of disaster response management, which has traditionally been executed from the top-down. But recently my perspective on the efficacy of the traditional approach has dramatically changed, namely when I helped organize a hackathon in San Francisco together with Thomas Maillart, Alexei Pozdnoukhov and Swissnex.34 The aim was to discover new ways to recover from earthquakes. Even though the event took place on the National Day of Civic Hacking and was therefore competing with a lot of other hackathons, it attracted about 80 people. Obviously, the event hit a nerve. Participants formed nine teams, each of which dealt with a specific project idea. The results established a new paradigm of disaster response management, facilitated by modern information systems.

Illustration of classical hierarchical top-down organization

Illustration of a superior combination of top-down and bottom-up organization

For this approach to be efficient and effective, it is important to have suitable tools to coordinate the various activities, and to match resources with needs. In fact, new information and communication tools can play a crucial role for this. Such platforms were often either absent or not publicly accessible in the past. Nowadays, however, the technology necessary to enable good coordination is widespread. For example, information platforms such as Ushahidi play a valuable role in mapping crises and responding to disasters. Let us now discuss how new information technologies can serve as survival toolkit in future disasters.

10.13 Towards a More Resilient Society

One of the three teams which won the hackathon, Amigocloud,35 came up with a smartphone app that allows everyone to take and annotate pictures of broken infrastructure and other problems, which are automatically uploaded to a public webpage whenever the mobile communication system is operational. When the central communication infrastructure is down, emergency connectivity can now also be provided by “meshnets”, whereby offline mobile devices form adhoc peer-to-peer networks to transfer information. This is possible using smartphone communication protocols such as FireChat.

Of course, for this we have to assume that the mobile phones’ batteries aren’t empty. However, the second winning team proposed Charge Beacons,36 i.e. autonomous local charging stations using solar panels, which allow citizens to recharge their smartphones even during a blackout. As a positive side effect, the Charge Beacons also serve as community hotspots where people meet.

The third winning team, Helping Hands, developed a smartphone app that allowed everyone to ask for and offer help. For example, one could request baby food, fresh water, or support for someone in need at a specific location. Others could offer clothes, water, food, or various kinds of support. The smartphone app would locally match resources with needs. This empowers the community to help itself and to harness the generosity witnessed during crises. As a consequence, the public disaster response teams will be able to focus more on providing aid in areas where people can’t help each other well enough. Thus, the above-described approach frees up resources for urgent and strategic matters. Consequently, both the citizens on the bottom and the governance system on the top will benefit. Remarkably, all of the above concepts emanated from a single hackathon, on a single day!

The observations of Yossi Sheffi in his book The Resilient Enterprise are also relevant in this context.37 He describes what it takes to keep a business running when struck by disaster. Sheffi (*1948) contends that the boss must provide a framework that allows the company’s experts to find solutions. However, he/she shouldn’t interfere with the details of this process, as attempts to micro-manage are often counterproductive. Instead, the aim should be to empower the staff to find solutions for themselves.

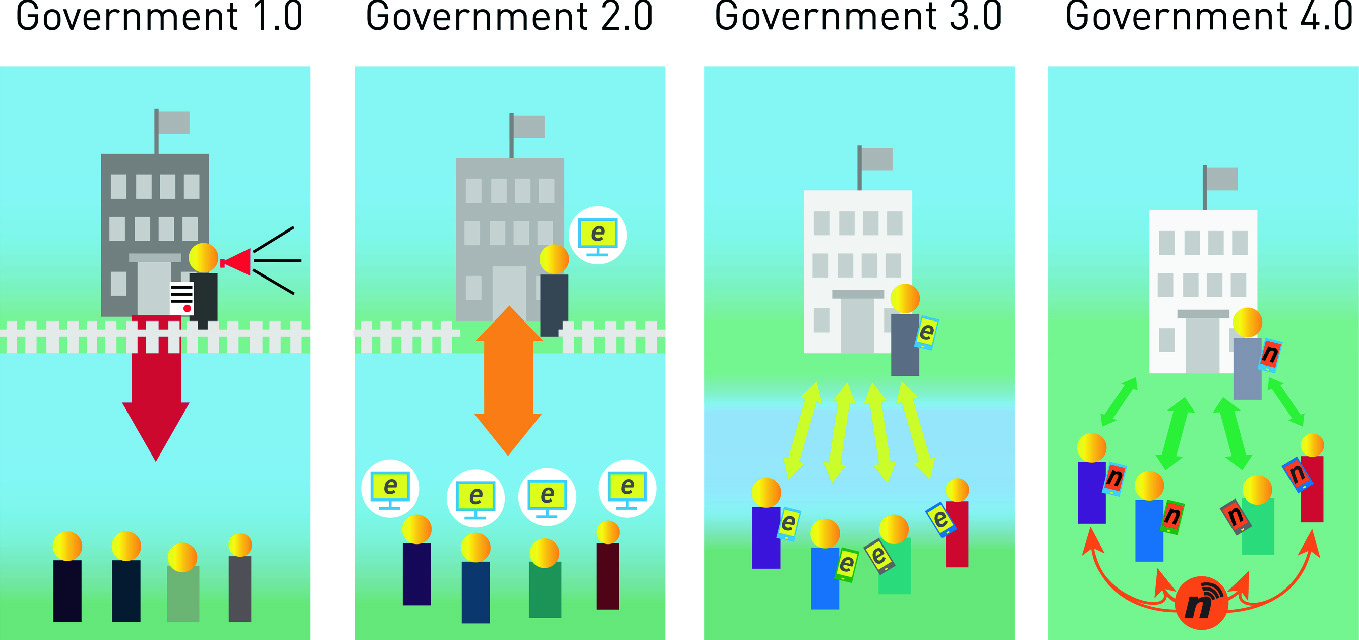

Illustration of the likely evolution of government models. Government 1.0 tells people what to do and is separated from its citizens. Government 2.0 uses electronic means to engage in a two-way interaction with its citizens. Government 3.0 engages in individually fitting interactions, services, and solutions. This is currently being implemented in South Korea. (You may want to watch this related movie list: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KgVBob5HIm8&list=PLDmlT_+Ptfv0fcMD29kNKOIhV0yK9AhyQl) Government 4.0 also builds on the coordination among its citizens and on mutual help, which establishes participatory resilience

10.14 A New Kind of Economy Is Born

As discussed above, the optimal organizational approach to disaster response management combines elements of both, centralized top-down control and distributed bottom-up organization. Could we adopt this approach not just in crisis situations, but every day? In fact, the creation of goods, services and knowledge in the emerging Economy 4.0 works exactly like this.

A critic might argue that I am “reinventing the wheel”, because some companies have already been managed this way. In fact, many companies subcontract work to third parties who can carry out tasks more efficiently. This works similarly to the suggested mode of organization illustrated in Figs. 10.2 and 10.3. However, most companies and institutions still seem to be governed predominantly in a top-down way.

While outsourcing avoids certain undesirable consequences, such as inefficiencies due to duplicate efforts and some other problems, too, it also prevents favorable things from happening. The same applies to hierarchical forms of organization. So, where do we have potentials for improvement?

Suppose a company experiences an economic downturn because it sells fewer products than expected. Traditionally, the firm would lay off employees to improve its balance sheet. However, one obvious reason why the company does not sell enough products is that it doesn’t offer enough interesting products that people would buy. Therefore, suppose the company decided to call for new product ideas from within the firm to make use of the knowledge, skills, and machinery at its disposal. This would probably generate several interesting ideas for new products, which could help to overcome the stagnation and the lack of innovation that large companies often experience. In other words, a company could offer its employees a platform (“playground”) that allows them to set up their own “projects” from the bottom-up. This would enable groups of staff to work autonomously on the development of new products for a limited period of time. Depending on the results, the company would then decide whether to close these units down or turn them into spin-off companies.

10.15 Emergence of a Participatory Market Society

While, in the past, most of us couldn’t participate in improving the man-made systems around us (because the tools necessary to coordinate the knowledge and skills of many people weren’t widely available), this is now changing. New information systems and organizational principles will allow individuals to actively engage as citizens in the public arena, as employees within firms, and as consumers and users within the production process. Therefore, if set up well, involving users, customers, and citizens will naturally lead to better services, better products, better businesses, better neighborhoods, smarter cities, and smarter societies. By building suitable platforms to coordinate information and action, we can create more opportunities, enable people, companies and institutions to make better decisions, and encourage people to act responsibly.

So far, I have discussed the growth of short-term projects, co-creation, home production, sharing, personalization, hyper-variety markets and the importance of bottom-up participation. Another crucial trend is the increasing relevance of “networked thinking”. In this connection, studying the Silicon Valley provides some interesting insights.

The Silicon Valley exhibits a surprisingly fluid exchange of people between companies. If a company goes bankrupt, which is quite common, people usually find a new job quickly. In a sense, it is not unreasonable to think of people as being employed on a long-term basis by the Silicon Valley rather than being employed on a short-term basis by its companies. In other words, the Silicon Valley is like a “super-company”, in which there is an invisible flow of knowledge and people that connects all of the companies located there. The companies themselves are the niches, in which experimentation can take place and among which a lot of diversity can exist. In effect, therefore, the Silicon Valley is nourished and sustained by the co-evolution of the companies and ideas within it.

Furthermore, it is instructive to view the interaction of companies within the Silicon Valley as forming a huge “information, innovation, production and service ecosystem”, where the various economic stakeholders may be compared to different biological species. For the economy to be in good shape, it is important that all of the sectors, which consume and produce, do well. If a significant part of the production ecosystem disappears, this is as if some species disappear, which can disrupt the entire economic ecosystem and cause a recession. In fact, in an interesting study, Cesar Hidalgo, Laszlo Barabasi, Ricardo Hausmann and others38 showed that economic development and prosperity largely depend on the economic diversity of this “ecosystem”, which mirrors the concept of biodiversity in nature. Similarly to the natural world, a greater diversity of economic production leads to more innovation and economic prosperity.

However, an “information, innovation, production and service” ecosystem can be organized in different ways. Fueled by almost unlimited amounts of venture capital, many innovators in the Silicon Valley aspire to build global monopolies. This creates “walled gardens”,39 between which very limited information exchange and cooperation exists. To build complex products, it is common to acquire other companies, but this reduces their usefulness for third parties.

To catch up and be competitive, Europe may take another route. After all, the organization of our economic system should serve our society best. Considering that data will be cheap (since we produce as much data in one year as in all the years before), it would make sense to engage in an Open Data approach and in open innovation, where “walled gardens” are avoided, but information exchange is built on merit-based principles. Money would be made by distilling useful information from raw data and by distilling applicable knowledge from information. By requiring differentiated interoperability, complex products could be created in a modular way by organizing “projects” into networks of projects. For such “super-projects” to grow in a self-organized way, the interaction must be mutually beneficial and will often involve a multi-dimensional value exchange (see Appendix 10.2).

As I explained in the previous chapter, evolutionary principles will anyway sooner or later cause a paradigm change from self-regarding to other-regarding forms of organization, since this produces better outcomes on average. For companies, this means that they need to communicate and cooperate more with their customers and suppliers. Next-generation social media will provide suitable tools for this. Companies that manage to offer individually tailored, customized products and services will have a competitive advantage. Obviously, this requires more information to be shared, and in order for this to be viable in the long term, a trustworthy and fair system of bidirectional communication and collaboration is crucial. As a consequence, the business leaders of tomorrow will have to be well acquainted with “systems thinking”, an approach which integrates and balances different interests and perspectives. Companies like Porsche, for example, are already aware that they can only produce and sell top-quality cars by engaging in a partnership with both their employees and their customers.40

10.16 Supporting Collective Intelligence

The challenges posed by the increasing complexity of our anthropogenic systems also call for more intelligence. Interestingly, collective intelligence can surpass the intelligence of smart people and powerful computers. It thrives in environments, where diverse knowledge and skills can come together. But collective intelligence isn’t possible, if decisions are taken from the top-down (as this is restricted to the intelligence of a single mind or a small circle of people). In comparison, majority decisions are often better than those of single individuals or centralized authorities, because they take more perspectives and knowledge on board. However, in our increasingly complex world, the outcomes of majority votes are also too limited, and the contributions of minorities become increasingly important. This is one of the reasons why more participatory ways of organizing our economy and society are emerging.

To foster collective intelligence we must build platforms allowing people to coordinate and integrate information so that they can learn, innovate, and produce collaboratively. The goal must be to create a participatory “information, innovation production, and service ecosystem”. This must provide sufficient niches for diverse, competitive problem-solving approaches, but also incentives for interoperability and cooperation. Furthermore, it must be sufficiently easy to integrate partial solutions in a modular way to reach higher-level goals. In fact, when thinking about the development of a modern car or plane, we immediately understand that some systems are so complex and require so many different skills that no one person can fully grasp all the details.

Importantly, by growing a diverse ecosystem in which many different approaches can co-exist and co-evolve, we will also make our society more resilient. The flexibility of this approach, furthermore, means that whatever happens, we will have a rich arsenal of options to respond. In contrast, the international trade and service agreements which have recently been negotiated may homogenize and standardize the world too much, and thereby eliminate the niches in which new ideas emerge and thrive.41 Niches provide necessary opportunities for experimentation. Indeed, this is why evolution is so effective.42 If we homogenize our socio-economic systems too much, they will be more vulnerable to disruption—with potentially disastrous consequences.

10.17 Preparing for the Future

What can we do to prepare ourselves for the Economy 4.0? In the past, we built public roads to facilitate the industrial society and public schools to provide the workforce for the service society. Now, we will need to build the public institutions for the digital society. This will include open and participatory information platforms, which will support people to make better decisions, to act more effectively, and to coordinate and help each other. In addition, participatory platforms should support creative projects and collaborative production.

In order to overcome the challenges ahead of us successfully, it is important to acknowledge that citizens, consumers, and users are essential for our society’s success and must be treated as partners—in a fair way and with respect. If we want to create new jobs, we must also increase opportunities for small and medium-size companies, and self-employed people. This can be reached by avoiding too much standardization while demanding differentiated interoperability, particularly from large companies. In this respect, incentivizing information exchange and Open Data is of key importance.43

Well-designed, participatory information platforms will help everyone to engage in the Economy 4.0 more effectively. They will support people in communicating more easily, identifying suitable partners to work with, coordinating activities, and collaboratively creating goods and services. Furthermore, such platforms could be used to do financial and project planning, to manage supply chains, to schedule processes, to carry out accounting, and to perform many other management tasks such as health insurance and tax administration. Such a platform could largely reduce the barriers of entry to the market and provide everyone with the tools needed to easily set up collaborative projects. In fact, future job and work platforms should have all of these features. Why don’t we build them as public infrastructures to foster the Economy 4.0?

10.18 Appendix 1: Re-Inventing Innovation

Compared to material goods, information is a special resource. While material goods are limited, which can lead to resource conflicts, information can be reproduced cheaply and as often as we like. Nevertheless, current intellectual property rights treat digital goods more or less like material goods. I believe, a different kind of intellectual property right (IPR) would dramatically accelerate innovation and create many more jobs. While we have to catch up with the pace at which our world is changing, the current IPR regime creates major obstacles. Therefore, we need a new paradigm which will allow collaborative creation (“co-creation”) to flourish.

In fact, we could fundamentally change the way we foster innovation. Currently, many people don’t like to share their best ideas, because they don’t want other people to become rich in the wake of their research, while getting very little compensation. As a result, it often takes years until an idea is shared with the world through a publication or patent. But what if we innovated cooperatively from the very first moment? Let us assume an idea is born in America, and it is shared with others through a public portal such as GitHub. Afterwards, experts from Asia could work on these ideas for a couple of hours, then experts from Europe could build on their results, and so on. In this way, we could create a research and development paradigm that never sleeps, that overcomes the limits of a single team, and that embraces “collective intelligence”.

Such an approach would produce considerable synergy effects. My colleagues Didier Sornette and Thomas Maillart recently demonstrated that, by open collaboration, two people can produce software that would otherwise have required 2.5 developers (“1 + 1=2.5”).44 Geoffrey West, Luis Bettencourt and I, together with some others, discovered a similar pattern in cities: productivity that depends on social interactions tends to disproportionately increase with population size.45 For example, a city with two million inhabitants would be about 20% more productive per 1 million inhabitants than two cities of one million. This is probably the main reason for the rapid and on-going urbanization of the world.

Interestingly, Internet forums of all kinds have nowadays created something akin to virtual cities. Many citizen science projects (and also the famous Polymath project on collaborative mathematics) underline that a crowd-based approach can complement or even outperform classical research and development approaches.46

Given the great advantages of collaboration, what are the main obstacles? A central problem is the lack of incentives to share. Currently, researchers are motivated by two kinds of rewards: they receive a basic salary and they earn the recognition by their peers in the form of citations of their published work. For this reason, many scientists do not share their ideas until they have been published.

Patents are a further obstacle to the sharing and widespread implementation of good ideas. While patents are actually intended to stimulate research and development by protecting the commercial value of ideas, in the digital economy patents seem to hinder innovation more than they foster it. It is as if everyone would own a certain number of words and could charge others for using them—this would certainly obstruct the exchange of ideas considerably.

However, it has recently become difficult to legally enforce hardware and software patents, and there have been an increasing number of patent deals between competing companies. The electric car company Tesla has even decided to allow others to use their patents.47 All this might indicate that a paradigm shift in terms of intellectual property rights is just around the corner.

Moreover, it has become increasingly difficult to earn large amounts of money by publishing music, movies or news. This is not just a problem of illegal downloads. In contrast to material resources, information is becoming an abundant resource. Given that every year, we produce as much data as in the entire history of humankind, information will become increasingly cheaper.

10.18.1 Micropayments Would Be Better

So why not pursue an entirely different IPR approach, perhaps in parallel to the current intellectual property regime? By it’s very nature, information “wants” to be free and to be shared. Every culture is based on this. Information is a virtually unlimited resource, which in principle can be reproduced almost for free. In contrast to material resources, this allows us to overcome scarcity, poverty and conflict. Nevertheless, we currently try to prevent people from copying digital products. What if we simply allowed copying, but introduced a micropayment system to ensure that every copy generates revenue for the content creator (and those who help to spread content)? Under such circumstances, we would probably love it when others copy our work!

Rather than complaining about people who copy digital products, we should make it easier to pay for the fruits of creativity and innovation. Remember that, some time back, Apple’s iTunes made it simple to download and buy songs, for 99 cents each. It would be great to have a similarly simple, automatic compensation scheme for digital products, ideas and innovations. Modern text-mining algorithms could form the basis of a system, where content creators and companies would be automatically paid whenever their ideas are used. This payment could be calibrated according to the scale of the initial investment, the age of the invention and its “innovativeness”, i.e. the degree to which it made advances over already existing solutions. This would encourage cooperative innovation without providing a disincentive for new research.

Establishing a micropayment system would also allow companies and citizens to earn money on the data they generate and exchange. Then, everyone could benefit from contributing to the global information ecosystem. This would create an incentive system that would reward the sharing of data. But to get paid for every copy, one would need a particular file format. Copies (“offspring”) of data would have to be linked with their respective source (“parent”) via a kind of “data cord”, so that micro-payments between the owners and users of the data can be processed.48 In fact, something like a “Personal Data Store” would be needed to execute these payments.49

10.19 Appendix 2: Multi-Dimensional Value Exchange

So far, we haven’t addressed the kind of financial system we will need for the Economy 4.0. In its current form, money has a serious short-coming: it is one-dimensional.50 This makes it unfit to manage complex dynamical systems. From the perspective of control theory, this problem is completely obvious. For example, complex chemical production processes cannot be governed using a single control variable such as the concentration of a particular chemical ingredient. In a complex production process, one must be able to control multiple variables, such as the temperature, pressure and concentration of numerous ingredients.

It is also instructive to compare this with ecosystems. The plant and animal life existing in a particular place is not solely determined by a single factor such as the amount of water. Temperature, humidity and various kinds of nutrients such as oxygen, nitrogen and phosphor play a role, too. Our bodies also require many kinds of vitamins and nutrients to be healthy. So why should our economic system be any different? Why shouldn’t a healthy financial system need several unrelated kinds of value exchange?51

It is helpful to recognize that the financial system is primarily a system to coordinate the use of resources. Therefore, we shouldn’t hesitate to invent better coordination mechanisms. For example, besides conventional money, our future value exchange system could consider environmental factors and other material and non-material externalities such as social capital (for example, trust and reputation).52 In fact, the Finance 4.0 system introduced in a later chapter does this.

10.19.1 We Could All Be Doing Well

The circumstance that people respond to many different kinds of rewards, as we have seen in the previous chapter, allows us to establish a multi-dimensional incentive and exchange system (which is very different from a nudging approach53). This system would support the self-organization of individuals and companies, which is highly important to successfully manage complex socio-economic systems in future. However, compared to the financial system we have today, such new forms of value would not necessarily be easily convertible. As a result—depending on how many dimensions of value we would distinguish—everyone could be doing well, when measured in the kind of value which best suits the personal strengths, skills and expertise54. That in itself is an interesting perspective worth pursuing!