We often celebrate the introduction of laws and regulations as historic milestones of our society. But over-regulation has become unaffordable, and better approaches are needed. Self-organization is the solution. As I will demonstrate, it is the basis of social order, even though it builds upon simple social mechanisms. These mechanisms have evolved as a result of thousands of years of societal innovation and determine whether a civilization succeeds or fails. Currently, many people oppose globalization because traditional social mechanisms fail to create cooperation and social order in a world, which is increasingly characterized by non-local interactions. However, in this chapter I will show that there are some reputation- and merit-based social mechanisms, which can still stabilize a globalized world, if well designed.

Since the origin of human civilization, there has been a continuous struggle between chaos and order. While chaos may stimulate creativity and innovation, order is needed to coordinate the actions of many individuals easily and efficiently. In particular, our ability to produce “collective goods” is of critical importance. Examples are roads, cities, factories, universities, theaters, and public parks, but also language and culture.

According to Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679), in the initial state of nature, everyone fought against everybody else (“homo hominis lupus”). To overcome this destructive anarchy, he claims, a strong state would be needed to create social order. In fact, even today, civilization is highly vulnerable to disruption, as sudden outbreaks of civil wars illustrate, or the breakdown of social order, which is sometimes observed after natural disasters. But we are not only threatened by the outbreak of conflict. We are also suffering from serious problems when coordination or cooperation fails, as it often happens in “social dilemma” situations.1

8.1 The Challenge of Cooperation

To understand the nature of “social dilemmas”, let us now discuss what it actually takes to produce “collective goods”. For this, let us assume that you have to engage with others to create a benefit that you can’t produce by yourself. In order to produce the collective good, we further assume that everyone invests a certain self-determined contribution that goes into a common “pot”. However, the size of these contributions is often not known to the others (and might actually be zero). The common pot could be a fund or also a tax-based budget. If the overall investment reaches a sufficient size, a “synergy” is created whereby the resulting value is higher than the initial investment. To reflect this, the total initial investment is multiplied by a factor greater than one. Finally, let’s assume for simplicity that all can equally benefit from the “collective good” (such as a public road) independently of how much they contributed (e.g. how much taxes they paid). Under these conditions it can happen that someone gets a benefit without contributing to the collective good, i.e. without making an investment.

In such social dilemma situations, creating benefits requires investments, but the outcome is uncertain. No individual can determine it alone. Specifically, if everyone invests enough, everyone will profit from the synergy. If you invest a lot while others invest little, you are likely to incur a loss. If you invest a little while others invest a lot, you may profit more than others. But if everyone invests only a little, the overall investment is too small to create a synergy effect and everyone will be worse off.

In such scenarios cooperation (contributing a lot) is risky, while free-riding (contributing little) is tempting. This discourages cooperative behavior. If the situation occurs many times, cooperation will be undermined and a so-called “tragedy of the commons” will result. Then, only a few will invest and nobody can benefit. Such situations are known, for example, from countries with high levels of corruption and tax evasion. Although cooperation would be beneficial for everyone, it breaks down in a similar fashion as free flowing traffic breaks down on a crowded circular track.2 This happens because the desirable state of the system is unstable.

8.2 When Everyone Wants More, but Loses

“Tragedies of the commons” occur in many areas of life. Frequently cited examples include the degradation of the environment, the abuse of social welfare systems, and climate change. In fact, even though probably nobody wants to destroy our planet, we still overexploit its resources and pollute the Earth to an extent that causes existential threats.3 As measured by the “environmental footprint”, many humans consume more resources than are being (re-)created, which leads to a globally unsustainable system. Moreover, although nobody would want to wipe out a species of fish, we are facing a serious overfishing problem in many areas of the world. Last but not least, even though schools, hospitals, roads and other useful public services require government funding, tax evasion is a widespread problem, and public debts are growing.

Of course, the conventional economic wisdom is that contracts can enforce cooperation, when legal institutions work well. Nevertheless, neither governments nor companies have so far managed to fully overcome the longstanding problems mentioned above. So, what other options do we have? In an attempt to address this question, the following paragraphs provide a short (and far from exhaustive) overview of the mechanisms which can encourage and sustain cooperation. These mechanisms have played a vital role in human history, and some of them have been so essential that they became cornerstones of world religions. This demonstrates that they are considered to be even more powerful than man-made institutions. In fact, rather than viewing history as a series of wars and treaties, we should view it as a series of discoveries which reshaped the ways societies are organized.

8.3 Family Relations

“Genetic favoritism” was a very early mechanism to promote cooperation. The scientific theory of genetic favoritism elaborated by George R. Price4 (1922–1975) posits that the genetically closer you are to others, the more it makes sense to favor them compared to strangers. The principle of genetic favoritism explains tribal structures and dynasties, which have been around for a long time. In many countries they still exist, and in some of them they come together with the custom of blood revenge. Today’s inheritance law still favors relatives. However, genetic favoritism has a number of undesirable side effects such as unequal opportunities for non-relatives, ethnic conflict, or vendetta. Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliette dramatically conveys the rigidity of family structures in the past very well. The caste system in India provides another example.

8.4 Scared by Future “Revenge”

What other options do we have to promote cooperation? It is known, for example, that cooperation becomes more likely, if people interact with each other many times. In such a setting, you may adopt a so-called “tit for tat” strategy to teach someone else that uncooperative behavior won’t pay off. The strategy is thousands of years old and was famously described in the Old Testament as “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth” (Exodus 21:24).

Today, the underlying success principle is called “the shadow of the future”. The effectiveness of revenge strategies was studied by Robert Axelrod (*1943) in a series of experimental computer tournaments published in 1981.5 It turns out that, if people interact frequently enough, a cooperative behavior is more beneficial than an exploitative strategy. As a consequence, “direct reciprocity” will result, where both parties act according to the principle “if you help me, I’ll help you”. But what if the friendship becomes so close that others are disadvantaged? This could lead to corruption and barriers preventing other people from competing fairly. In an economic market, this could result in inefficiency and higher prices.

In addition, what should we do if we interact with someone only once, for example, on a one-off project such as the renovation of a flat? Are such interactions doomed to be uncooperative and inefficient? And what should we do if a social dilemma involves many players? In such cases, a tit-for-tat strategy is too simple because we don’t know who cheated whom.

8.5 Costly Punishment

For such reasons, further social mechanisms have emerged, including “altruistic punishment”. As Ernst Fehr and Simon Gächter have shown in 2002,6 if players can punish others, this will promote cooperation, even if the punishment is costly. Indeed, if people can choose between a world without sanctions and a world where misbehavior can be punished, many decide for the second option, as evidenced by experimental research conducted in 2006 by Özgür Gürek, Bernd Irlenbusch and Bettina Rockenbach.7 Punishment played a particularly important role in the beginning of the experiment. Later on, people behaved more cooperatively, and although punitive sanctions became rare, they were nevertheless important as a deterrent.

Note that punishment by “peers”, as it was studied in these experiments, is a very widespread social mechanism. In particular, it is used to establish and maintain social norms, i.e. certain behavioral rules. Every one of us exercises peer punishment many times a day—perhaps in a mild way by raising eyebrows, or perhaps more assertively by criticizing others or engaging into conflict, which is often costly for both sides.

8.6 The Birth of Moral Behavior

But why do we punish others at all, if this is costly, while others benefit from the resulting cooperation? This scientific puzzle is known as “second-order free-rider dilemma”. The term “free-rider” is used for someone who benefits from a collective good without contributing. “First-order free-riders” are people who don’t cooperate, while “second-order free-riders” are people who don’t punish the misdeeds of others.

Snapshots of a computer simulation showing the spread of moral behavior (green) in competition with cooperators who don’t punish (“secondorder free-riders”, in blue), with non-cooperative individuals (“defectors”, in red), and with people who neither cooperate nor punish (“hypocritical individuals”, in yellow) (Reprinted from Helbing et al. [6]. Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.)

When agents from the entire population are randomly matched for interactions, moralists are disadvantaged by the punishment costs as compared normal cooperators. In other words, moralists cannot compete with second-order free-riders, who abstain from sanctions. Consequently, moralists disappear and cooperators meet defectors. The result is a “tragedy of the commons”. Altogether, individuals trying to act according to their rational self-interest create an outcome that is ultimately detrimental to everyone’s interests.

Surprisingly, however, when individuals interact with a small number of neighbors, clusters of people who adopt the same kind of behavior emerge (see Fig. 8.1). The fact that “birds of a feather flock together”10 makes a big difference. It allows moralists to thrive! While cooperators still make lower profits than defectors, moralists, who cooperate and punish uncooperative behavior of others, can now succeed. This is due to the fact that the different types of behavior are separated from each other in space. In particular, moralists (shown in green in Fig. 8.1) tend to be separated from cooperators (shown in blue) by defectors (shown in red). At the boundaries of their respective clusters, both of them have to compete with non-cooperative agents (yellow or red). While cooperative agents are exploited by non-cooperative ones, moralists sanction non-cooperative behavior and can, therefore, succeed and spread.

This is amazing! While random interactions cause a “tragedy of the commons” where nobody cooperates and nobody makes a profit, we find just the opposite result if people interact with their neighbors in space or in a social network, where the same behaviors tend to cluster together. Therefore, a small change in the way interaction partners are chosen can create conditions under which moral behavior can prevail over free-riding.

8.7 Containing Crime

Nevertheless, punishing each other is often annoying or inefficient. This is one of the reasons why we may prefer to share the costs of punishment, by jointly investing in sanctioning institutions such as a police force or court. This approach is known as “pool punishment”. A problem with this strategy, however, is that police, courts and other sanctioning institutions may be corrupted. In addition, it is sometimes far from clear who deserves to be punished and who is innocent.11 For the legitimacy and acceptance of such institutions, it is important that innocent people are not punished in error. This means that extensive inspections and investigations are required, which can be costly compared to the number of people who are finally convicted.

In 2013, Karsten Donnay, Matjaz Perc12 and I developed a computer model to simulate the spread and fighting of criminal behavior. We were astonished to find that greater deterrence in the form of more surveillance and higher punishment would not eliminate crime.13 People don’t just make a calculation whether crime pays off or not, as is often assumed. Instead, crime is kind of “infectious”, but punishment and normal behavior are contagious, too. This can explain the surprising crime cycles that have often been observed in the past. As a consequence, a crime prevention strategy based on alleviating socio-economic deprivation might be much more effective than one based on deterrence.

8.8 Group Selection

Things become trickier if we have several groups with different preferences, due to different cultural backgrounds or education, for example.14 Then, a competitive dynamics between different groups may set in. The subject is often referred to as “group selection”, which was put forward by Vero Copner Wynne-Edwards (1906–1997) and others.15

It is often believed that group selection promotes cooperation. Compare two groups with high and no cooperation. Then, the cooperative group will get higher payoffs and grow more quickly than the non-cooperative group. Consequently, cooperation should spread and free-riding should eventually disappear. But what would happen if there were an exchange of people between the groups? Then, free-riders could exploit the cooperative group and quickly undermine the cooperation within it. For such reasons, people often fear that migration would undermine cooperation. But it doesn’t have to be like this.

8.9 The Surprising Role of Success-Driven Migration

To study the effect of migration on cooperation, back in 2008/09, Wenjian Yu and I developed a related agent-based computer model.16 We made the following assumptions: (1) Computer-simulated individuals (called “agents”) move to the most favorable location within a certain radius of their current location (“success-driven migration”). (2) They tend to imitate the behavior of the most successful individuals they interact with (their “neighbors”). (3) There is some degree of “trial-and-error behavior”, i.e. a certain probability that each individual will either migrate to a free location, which isn’t occupied already, or change the behavior (from cooperative to noncooperative or vice versa). While rule (1) does not change the number of people who cooperate, the other two rules tend to undermine significant levels of cooperation. Surprisingly, however, when all three rules are applied together, a high level of cooperation is eventually achieved. This proved to be true even in cases where the simulation began with no cooperative agents at all, a situation akin to the “state of nature” assumed by Thomas Hobbes. So, how is it possible that cooperation flourishes in our computer simulation, in spite of the fact that there is no powerful state (a “Leviathan”) to ensure cooperation from the top-down?

The answer relates to the unexpected way success-driven migration affects the competition between cooperative and uncooperative agents. Even though we didn’t initially expect that migration would influence cooperation a lot, we put the assumption to the test because of my interest in human mobility. In our computer simulations, migration first spread people out geographically. This isn’t good for cooperation at all, but as individuals occasionally change their strategies due to trial-and-error behavior, cooperative behaviors may sometimes occur for a short time. Such accidental cooperation happens in random places. However, after a sufficiently long time, some of these cooperative events happen to be located next to each other. In case of such a coincidence, i.e. when a big enough cluster of cooperative behaviors occurs, cooperation suddenly becomes a successful strategy, and neighbors begin to imitate this behavior. As a result, cooperation quickly spreads throughout the entire system.

How does this mechanism work? To avoid losses, cooperative individuals obviously move away from uncooperative agents, but they engage repeatedly in interactions with cooperative neighbors. In other words, cooperative behavior is sustainable over several interactions, while non-cooperative behavior is successful only for a short time, as exploited neighbors will move away. This leads to the formation of cooperative clusters, with a few uncooperative individuals at the boundaries. Thus, the individual behavior and spatial organization evolve in tandem, and the behavior of an individual is determined by the behavior in his/her surrounding, the “social milieu”.

In conclusion, when people are allowed to move around freely and to live in the place they prefer, this can promote cooperation.17 Thus, migration is not a problem, if there are opportunities for integration. But integration is not just the responsibility of migrants—it requires an effort from both sides, the migrants and the host society.

Although it has been a constant feature of human history, migration is not always welcomed. There are understandable reasons for this weariness; many countries are struggling to manage migration and integration successfully. However, the USA, known as the cultural “melting pot”, is a good example of the positive potential of migration. This success is based on a tradition, where it is relatively easy to interact with strangers.

Another positive example is provided by the Italian village of Riace.18 Although picturesque, the village is located in one of Italy’s poorest regions. The service sector gradually disappeared as young people moved away to other places. But one day, a boat with migrants stranded off the coast of Italy. The mayor viewed this as a sign from God, and decided to use it as an opportunity for his village. Indeed, something of a miracle occurred. The arrival of the migrants revived the ailing village, and the gradual decay was reversed with the migrants. Crucially, migrants were not treated as foreigners, but as an integral part of the community, which fostered a relationship of mutual trust.

8.10 Common Pool Resource Management

Above, I have described many simple social mechanisms that have proved their effectiveness and efficiency in mathematical models, computer simulations, laboratory or real-life settings. But what about more complex socio-economic systems? Would suitable social mechanisms be able to create a desirable and efficient self-organization of entire societies? Elinor Ostrom (1933–2012), in fact, performed extensive field studies addressing this question, and in 2009, she won the Nobel Prize for her work.

Conventional economic theory posits that public (“common-pool”) resources can’t be efficiently managed, and therefore should be privatized. Elinor Ostrom, however, discovered that this is wrong. She studied the way in which common-pool resources (CPR) were managed in Switzerland and elsewhere, and found that self-governance is efficient and leads to cooperation, if the interaction rules are appropriate. A successful set of rules is specified below:19

- 1.

The boundaries between in- and out-groups must be clearly defined (to effectively exclude external, un-entitled parties).

- 2.

The possession and supply of common-pool resources must be governed according to rules that are tailored to the specific local conditions.

- 3.

A collective decision-making process is required that involves the agents who are affected by the use of the respective resources.

- 4.

The supply and use of common-pool resources must be monitored by the people who manage the common-pool resources or people who are accountable to them.

- 5.

Sanctions of proportionate severity must be imposed on people who use common-pool resources in violation of the community rules.

- 6.

Conflict resolution procedures must be established which are cheap and easy to access.

- 7.

The self-governance of the community must be recognized by the higher-level authorities.

- 8.

In case of larger systems, they can be organized into multiple layers of “nested enterprises”, i.e. in a modular way, with smaller local CPRs at the base level.

Note, however, that collective goods can be created even under less restrictive conditions.20 This amazing fact can, for example, be observed in the communities of volunteers who have created Linux, Wikipedia, OpenStreetMap, Stack Overflow or Zooniverse.

8.11 Why and How Globalization Undermines Cooperation and Social Order

The central message of this chapter is that self-organization based on local interactions is at the heart of all human societies. Since the genesis of ancient societies right up until today, a great deal of social order emerges from the bottom-up. To achieve cooperation, one just needs suitable interaction mechanisms (“rules of the game”), including mechanisms to reach compliance with the rules. This approach tends to be flexible, adaptive, resilient, effective and efficient.

Most of the previously discussed mechanisms enable self-organized cooperation in a bottom-up way by encouraging people to engage in social interactions with others who exhibit similar behavior—“birds of a feather flock together”. The crucial question is whether these mechanisms will also work in a globalized world? These days, many people and governments feel that globalization has undermined social and economic stability. As I will demonstrate in the following, this is actually true, and the underlying reasons are quite surprising.

Globalization means that an increasing variety of people and corporations interact with each other, often in a more or less anonymous or “random” way. This leads to a surprising problem, which is illustrated by a video produced in my team.21 The video illustrates a circle of “agents” (such as individuals or companies), each of whom is creating collective goods with agents in their vicinity. These local interactions initially foster a high level of cooperation for reasons that we have discussed above. When further interactions with randomly chosen agents are added, the level of cooperation first increases. Therefore, it seems natural to add more interaction links. However, there is an optimal level of connectivity, beyond which cooperation starts to decay.22 When everyone interacts with everyone else, finally, cooperation even stops completely. In other words, when too many people interact with each other, a “tragedy of the commons” results, and everyone suffers from the lack of cooperation. Therefore, the way we are globalizing the world today may lead to the erosion of social order and economic stability. This conclusion is also supported by the Chief Economist at the Bank of England, Andrew Haldane (*1967), who suggests that the financial meltdown in 2008 resulted from a hyperconnected banking network.23

8.12 Age of Coercion or Age of Reputation?

In an attempt to stabilize our socio-economic system, many governments have tried to (re-)establish social order from the top-down, by increasing surveillance and investing into armed police. However, this control approach is destined to fail due to the high level of systemic complexity, as I pointed out before. In fact, we have seen a lot of evidence of this failure24. The signs of economic, social and political instability are all around us. Therefore, it is conceivable that our globalized society might disintegrate and break into pieces, thereby creating a decentralized system.

Is there a way to avoid such a fragmentation scenario? Can globalization be realized in such a way that cooperation and social order remain stable? Given that it is possible to stabilize the traffic flow using traffic assistance systems, can we also build an assistance system for cooperation? In fact, there are a number of new possibilities, which I will discuss now.

8.13 Costly, Trustworthy Signals

Illustration of the competitive setting of a laboratory experiment we performed (Reproduction from Mäs and Helbing [18].)

We gained a number of remarkable insights. First, the competitive setting led to higher investments in both teams. Second, it was interesting to see how well different mechanisms perform when competing with others. In our experiment, “costly punishment” was compared with no mechanism supporting cooperation (“no institution”) and with three kinds of “signaling”, which allowed players to indicate beforehand that they were willing to invest into their team’s pot. “Free signaling” did not require one to pay anything to send a signal to the own team; “costly signaling” required one to pay a fee; “altruistic signaling” was costly, but the fee was paid to the other team members and split between them. In terms of the probability of winning, “costly punishment” beat all other options and “altruistic signaling” was the second-best option. “No institution” was more effective than “free signaling”, which was again more successful than “costly signaling”.

However, when considering punishment and signaling costs, costly punishment was actually not the most efficient mechanism. The winner was altruistic signaling! Therefore, signaling allows people to coordinate themselves and to cooperate efficiently, if signaling has a price. Free signaling, in contrast, is not a credible way of communicating someone’s intentions, because cheap talk invites people to lie. In summary, there are better social mechanisms than punishing non-cooperative behavior. “Altruistic signaling” is one of them.

8.14 Building on Reputation

There is a further important interaction mechanism to support cooperation, which we haven’t discussed yet. The underlying principle is to help others, as described, for example, in the parable of the good Samaritan (New Testament, Luke 10:29–37). The commandment “Love your neighbor as yourself” (Mark 12:31) points in the same direction. Many world religions and philosophies support similar principles of action.25 In fact, if all people behaved in an other-regarding way, others would help them, too. Based on this “indirect reciprocity”, a high level of cooperation would result, and everyone could have a better life. But there is a problem: if some agents comply with this rule and other don’t, friendliness can be exploited.

Nevertheless, there is a solution: reputation mechanisms allow people and companies with compatible preferences and behaviors to find each other. They help “birds of a feather” to flock together on a global scale and to avoid bad experiences.

The value of reputation and recommendation systems is evidenced by the fact that they are quickly spreading throughout the Web. People seem to relish the opportunity to rate products, news and comments. But why do they bother? In fact, they get useful recommendations in exchange, as we know from platforms such as Amazon, eBay, TripAdvisor and many others. Wojtek Przepiorka has found that such recommendations are beneficial not only for users, who tend to get a better service, but also for companies.26 A better reputation allows them to sell products or services at a higher price. Many hotels, for example, use their average score on TripAdvisor as a key selling point.

8.15 A Healthy Information Ecosystem by Pluralistic Social Filtering

How should reputation systems be designed? It is certainly not good enough to leave it to a company to decide, how we see the world and what recommendations we get. This promotes manipulation and undermines the “wisdom of the crowds”, resulting in bad outcomes.27 It is important, therefore, that recommendation systems do not reduce social diversity. Moreover, we should be able to look at the world from our own perspective, based on our own values and quality criteria. Otherwise, we may end up trapped in what Eli Pariser (*1980) calls the “filter bubble”.28 In such a scenario, we may lose our freedom of decision-making and our ability to communicate with others who have different points of view. In fact, some people believe that this is already the case and one of the reasons why political compromise between Republicans and Democrats in the US has become so difficult.29 As a consequence, conservatives and liberals in the US consume different media, interact with different people, and increasingly use different concepts and different words to talk about the same subjects. In a sense, they are living in different, largely separated worlds.

Clearly, today’s reputation systems are not good enough. They would have to become more pluralistic. For this, users should be able to assess not just the overall quality, which is typically quantified on a simple five-point scale or even in a thumbs-up-or-down system. The reputation systems of the future should include different facets of quality such as physical, chemical, biological, environmental, economic, technological and social qualities. These characteristics could be quantified using metrics such as popularity, level of controversy, durability, sustainability, and social factors.

It would be even more important that users can choose among diverse information filters, and that they can generate, share and modify them. I call this approach “pluralistic social filtering”.30 In fact, we could have different filters to recommend us the latest news, the most controversial stories, the news that our friends are interested in, or a surprise filter. Then, we could choose among a set of filters that we find useful. To assess credibility and relevance, these filters should ignore sources of information that we regard as unreliable (e.g. anonymous ratings) and put a focus on information sources that we trust (e.g. the opinions of friends or family members). For this purpose, users should also be able to rate and comment on products, companies, news, information, and sources of information. If this were the case, spammers would quickly lose their reputation and their influence would wane.

In concert, all personalized information filters together would establish an “information ecosystem”, where filters would evolve by modification and selection. This would steadily enhance our ability to find meaningful information. As a result, the personalized reputational value of each company and their products would give a differentiated picture, which additionally would help firms to customize their products. Hence, reputation systems can have advantages for both, consumers and businesses, which creates a win-win situation.

In summary, while societies all over the world are still buckling under the pressure of globalization, a globalized world does not need to produce social and economic instability. By creating global, pluralistic reputation systems, we can build a well-functioning “global village”. This is achieved by matching people or companies with others who share compatible interests. However, it will be crucial to design reputation systems in such a way that they allow privacy and innovation to thrive. Furthermore, future reputation systems should be resistant to manipulation. Appendix 7.1 provides some ideas on how this may be achieved.

8.16 Merit-Based Matching: Who Pays More Earns More

Note that most cooperation-enhancing mechanisms, including special kinds of contracts between interaction partners, modify interactions in a way that turn a social dilemma situation into something else. Such a transformation is also often reached by taxing undesirable behaviors or by offering tax reductions for favorable behaviors. In other words, the payoff structure is changed in a way that makes cooperation a natural and stable outcome.31

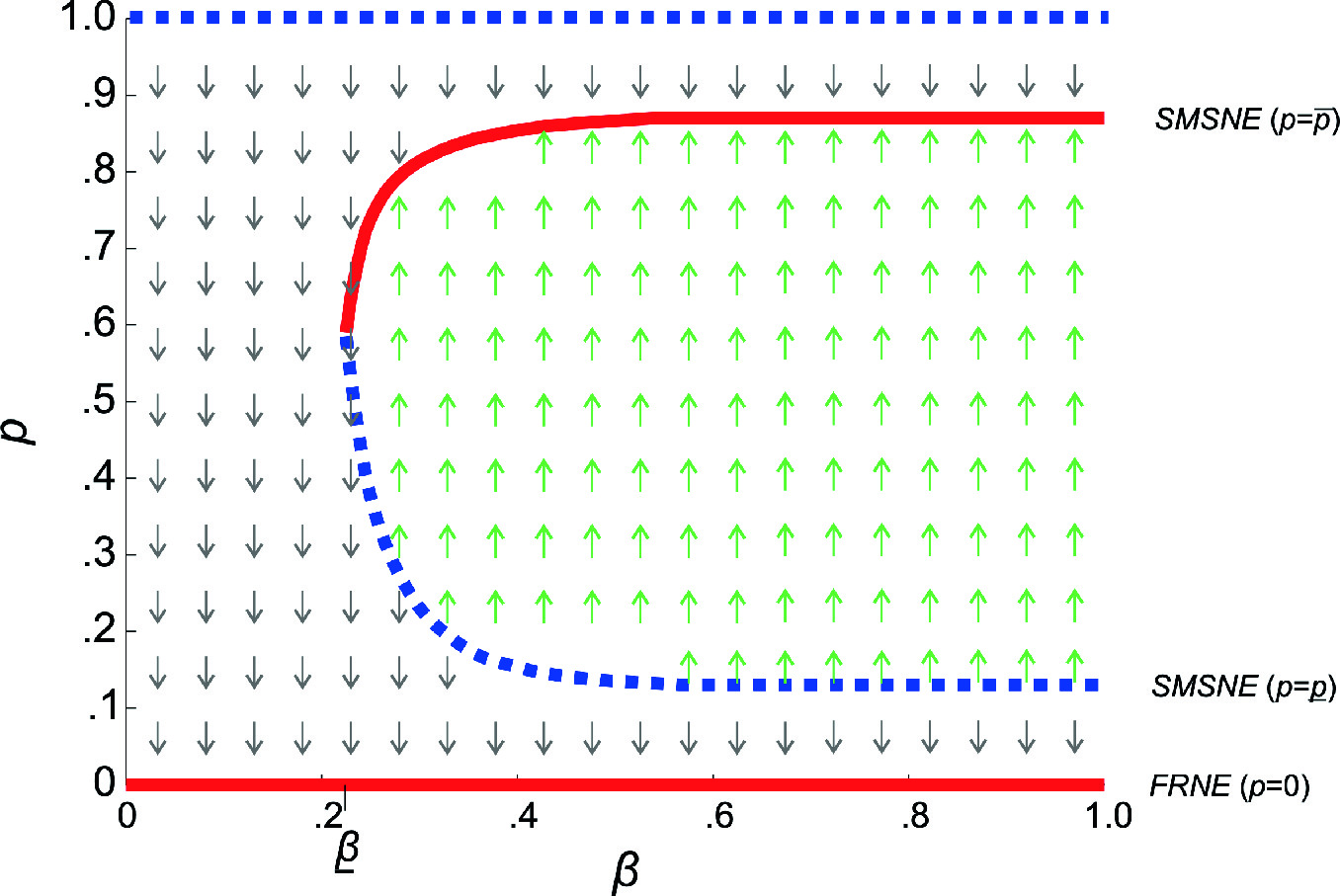

However, there is also another mechanism to promote cooperation, which is quite stunning. This mechanism, which I proposed together with Sergi Lozano,32 introduces an additional feedback loop in the social system, whereby more complex dynamic interdependencies and additional solutions are produced. When Heinrich Nax joined my team, we elaborated an example implementation of this mechanism, which is based on “merit-based matching”.33 Accordingly, agents who have contributed much to a collective good are matched with other high-level contributors, and those who have contributed little are matched with similar agents. The exciting result of this matching mechanism is: who pays more earns more! Furthermore, over time this effect encourages others to invest more as well, such that a trend towards higher investments and more cooperation is reached (see Fig. 8.3). Therefore, merit-based matching in social dilemma situations can turn the downward spiral, which would lead to a “tragedy of the commons”, into an upward spiral.

Illustration of the probability p of cooperation as a function of how perfectly people are matched in a merit-based way. Merit-based matching produces a trend towards a higher level of cooperation (see green upward arrows). (Adapted from Nax et al. [25]. Reproduction with kind permission of Heinrich Nax.)

8.17 Social Technologies

The above discussion has illustrated that cooperation usually doesn’t fail due to bad intentions, but because it is unstable in social dilemma situations. Moreover, we have learned that punishment isn’t the best mechanism to stabilize cooperation. In multi-cultural settings, it rather tends to create conflict, i.e. the breakdown of social order. But most of the time a suitable coordination mechanism is sufficient to stabilize cooperation. In the past, such coordination mechanisms haven’t always been available to everyone, but information systems can now change this. Altruistic signaling, reputation systems and merit-based matching are three promising new ways to foster cooperation, which are based on information systems rather than punishment. However, we could build much more sophisticated digital assistants to create social order and further benefits.

As we have seen before, many problems occur when people or companies don’t care about the external effects of their decisions and actions on others (i.e. so-called “externalities”). As “tragedies of the commons” or wars demonstrate, this can be harmful for everyone. So, how can we encourage more responsible behavior and create sustainable systems? The classical approach would be to devise, implement and enforce new legal regulations. But people don’t like to be ruled, and our labyrinthine legal systems already leads to confusion, inefficiency, loopholes, and high costs. As a consequence, laws are often ineffective. However, Social Technologies offer a new opportunity to create a better world, by supporting favorable local interactions and self-organization. It’s actually easier than you might think, and it’s completely different from nudging, which tricks people.

8.18 Digital Assistants

When two people or companies interact, there are just four possible outcomes, which relate to coordination failures and conflicts of interest. The first possibility is that of a lose-lose situation. In such cases, it is best to avoid the interaction altogether. For this, we need information technologies that make us aware of expected negative side effects associated with an interaction: if we know the social and environmental implications of our interactions, we can make better decisions. Therefore, measuring the externalities of our actions is important in order to avoid unforeseen damage. In fact, if we had to pay for negative externalities of our decisions and actions and if we would earn on positive externalities, this would help us to reduce the divergence between private and collective interests. As a result, self-interested decisions of individuals and companies would be less likely to cause economic or environmental damage.

The second possibility is a bad win-lose situation. In such cases, one party is interested in the interaction, but the other side would like to avoid it, and the overall effect would be negative. In such situations, increasing awareness may help, but social mechanisms to protect people (or firms) from exploitation are necessary, too. I will address this in detail in Appendix 7.2.

The third possibility is a good win-lose situation. While the interaction would benefit one party at the expense of another, there would be an overall systemic benefit from the interaction nevertheless. Obviously, in this scenario one party would like to engage, while the other would like to avoid the interaction. It is possible, however, to turn such win-lose situations into win-win situations by compensating the otherwise losing party. For this, a value exchange system is needed. Then, the interaction can be made mutually beneficial and attractive.

Finally, the fourth possibility is a win-win situation. Although both parties profit, one may decide to divide the overall benefit in a fair way. Again, this requires a value exchange system. In addition, cooperation can be fostered by making people aware of opportunities they might otherwise miss. In fact, every day we walk past hundreds of people who share interests with us while we don’t know about it. In this respect, digital assistants can help us take advantage of opportunities that would otherwise be missed, thereby unleashing an unimaginable socio-economic potential. If we had suitable information systems to assist us, we could easily engage with people of diverse cultural backgrounds and interests in ways that create opportunities and avoid conflict.

The above-described Social Technologies can now be built. Smartphones are already becoming digital assistants to manage our lives. They help us to find products, nice restaurants, travel routes and people with similar interests. They also enable a real-time translation from one language to another. In future, such digital assistants will pay more attention to the interactions between people and companies, producing mutual benefits for all involved. This will play an important role in overcoming cultural barriers and in minimizing environmental damage, too.

Eventually, Social Technologies will help us to avoid bad interactions, to discover and take advantage of good opportunities, and to transform potentially negative interactions into mutually beneficial cooperation. In this way, the “interoperability” between diverse systems and interests is largely increased, while coordination failures and conflicts are considerably reduced. I am, therefore, convinced that Social Technologies can produce enormous value, both material and immaterial. Some social media platforms are now worth billions of dollars. How much more value could digital assistants and other Social Technologies create?

8.19 Appendix 1: Creating a Trend for the Better

For reputation systems to work well, there are a number of things to consider: (1) the reputation system must be resistant to manipulation; (2) people shouldn’t be subject to intimidation or unsubstantiated allegations; (3) to enable individuality, innovation and exploration, the “global village” shouldn’t be organized like a rural village in which everyone knows everyone else and nobody wishes to stand out. We will need a good balance between accountability and anonymity, which ensures the stability of the social system.

Therefore, people should be able to post ratings or comments either anonymously, pseudonymously or using their real-world identity. However, posts using real-world identities might be weighted 10 times higher than pseudonymous ones, and pseudonymous posts might be weighted 10 times higher than anonymous ones. In addition, everyone who posts something should have to declare the category of the information. Such categories could, for example, be: facts, opinions and advertisements. Facts would need to be potentially falsifiable and corroborated by publically accessible evidence. In contrast, a subjective assessment of people, products or events would be considered to be an opinion. Finally, advertisements would need to include an acknowledgement of potential personal or third-party benefits. Ratings would always be categorized as opinions. If people would use the wrong categories or post false information (as identified and reported by, say, 10 others), their online reputation would be reduced by a certain amount (say, by a factor of 2). Mechanisms such as these would help to ensure that manipulation or cheating wouldn’t pay off.

Furthermore, one should ensure the right of informational self-determination, such that individuals are able to determine the way their personal information (such as social, economic, health, or private information) is used. This could be realized with a Personal Data Store.35 In particular, a person should be able to stipulate the purpose and period of time for which their information is accessible and to whom (everyone, non-profit organizations, commercial companies, friends, family members or particular individuals, for example). These settings would enable a select group of individuals, institutions, or corporations to access certain personal information, as determined by the users. Of course, one might also decide not to reveal any personal information at all. However, I expect that having a reputation for something would be better for most people than having no digital image, if only to find people who share similar preferences and tastes.

8.20 Appendix 2: Towards Distributed Security, Based on Self-Organization

Let me finally address the question whether bottom-up self-organization is dangerous for society? In fact, since the Arab Spring, governments all over the world are afraid of “twitter revolutions”. Therefore, are social media destabilizing political systems? Do governments need to censor free speech or control the algorithms that spread messages through social media platforms? Probably not. First, the Arab Spring was triggered by high food prices,36 i.e. deprivation, and not by anarchism. Second, encroaching on free speech would obstruct our society’s ability to innovate and to detect and address problems early on.

But how to reach a high level of security in a system which is based on the principle of distributed bottom-up self-organization? Let me give an example. One of the most astonishing complex systems in the world is our body’s immune system. Even though we are bombarded every day by a myriad of viruses, bacteria and other harmful agents, our immune system protects us pretty well for about 50–100 years. Our immune system is probably more effective than any other protection system we know. What is even more surprising is that, in contrast to our central nervous system, the immune system is organized in a decentralized way. This is no coincidence. It is well known that decentralized systems tend to be more resilient to disruptive events. While targeted attacks or local disruptions can make a centralized system fail, a decentralized system will usually survive such disruptions and recover. In fact, this is the reason why the Internet is so robust.37 So why don’t we protect information systems using in-built “digital immune systems”?38 This should also entail a reputation system, which could serve as a kind of “social immune system”. In the following, I will describe just a few aspects of how this might work.

8.20.1 Community-Based Moderation

Information exchange and communication on the Web have quickly changed. In the beginning, there was almost no regulation in place. These were the days of the “Wild Wild Web”, and people often did not respect human dignity and the rights of companies when posting comments. However, one can see a gradual evolution of self-governance mechanisms in open and participatory systems over time.

Early on, public comments in news forums were published without moderation. This led to a lot of low-quality content. Later, comments were increasingly checked for their legality (and for their respect of human dignity) before they went online. Then, it became possible to comment on comments. Now, comments are rated by readers, and good ones get pushed to the top. The next logical step is to rate commenters generally39 and rate the quality of judgments of those who rate others. Thus, we can see the gradual evolution of a self-governing system that constructively channels free speech. Therefore, I believe that it is possible to encourage responsible use of the Internet, mainly through self-organization.

The great majority of malicious behavior can probably be controlled using crowd-based mechanisms. Such approaches include reporting inappropriate content and ranking user-generated content based on suitable reputation mechanisms. To handle the remaining, complicated cases, one can use a system of community moderators and complaints procedures. Such community moderators would be determined based on their performance in satisfying lower-level community expectations (the “local culture”), while staying within the framework set by higher-level principles (such as laws and constitutional principles). In this way, community moderators would complement our legal framework, and most problems could be solved in a community-based way. Therefore, only a few cases will require legal mediation. Most activities would be self-governed through a system of sanctions and rewards by peers. In the following chapters, I will explain in more detail how information technology will enable people and companies to coordinate their interests in entirely new ways.