“Modern Heroes”

Moderating in Manila

Commercial Content Moderation in Manila: The Dating App Datakeepers of Eastwood City

On a stifling day in Manila, in May 2015, I sat in the back of a taxi as its driver deftly swerved in and out of bumper-to-bumper traffic, weaving around small motorbikes and scooters, past the uniquely Filipino form of mass transit known as “jeepneys,” through neighborhoods populated by street vendors and small shops offering household wares and hair styling. Signs on buildings advertised “no brownouts,” but precarious tangles of electrical cables suggested otherwise. In the distance, above the narrow alleyways off the main street, I caught glimpses of construction cranes and glittering towers of skyscrapers on the rise. Despite the adeptness of the driver in navigating the many obstacles, I felt queasy. We made our way to an expressway. On the shoulder, I watched as a brave and committed soul flew by our car on his Cervélo road bike as our taxi ground to a halt in stifling traffic.

A neighborhood scene as viewed on the taxi ride to Eastwood City from Makati City, Manila, the Philippines.

We had an appointment to keep with a group of strangers I had never met, in a city and culture I was largely unfamiliar with, and the likelihood of arriving on time ticked away by the second. A colleague at my workplace, herself a native of Manila, had warned me that May would be the worst time of year for someone unaccustomed to the oppressive heat of the city to visit. She was right. I felt my carefully groomed and presentable self slipping away with each rivulet of perspiration beading on my forehead and rolling down my neck. My traveling companion, Andrew Dicks, an experienced graduate student researcher, had less trouble dealing with the climate, having spent many years living and conducting research in Southeast Asia. But even he, too, was wrinkled and damp. We sat silently in the back seat, as both of us were anticipating the day’s work ahead, trying to conserve our energy in the heat.

Just as I felt certain I would not be able to stand any more heat, fumes, or weaving, the driver made a series of adroit moves, turning off the highway and on to a curving drive graced with carefully groomed tropical landscaping. He pulled over, and we stepped out on a beautiful foliage-lined walkway next to a sign announcing “Eastwood City.” The meeting location had been chosen by a group of young workers who labored in one of Manila’s countless “business process outsourcing” centers, or call centers, as they are commonly known. Unlike typical call center staff, the people who we had traveled to see performed a specialized, distinct type of work.

Rather than answering phones, these young people were, of course, commercial content moderators. They spent their days combing through the profiles of the primarily North Americans and Europeans who used a mobile phone dating app with millions of users. From their headquarters halfway around the globe, the app developer had outsourced its moderation work to a business process outsourcing (BPO) firm in the Philippines. The Filipino content screeners sifted through information uploaded by app users and banished what under the app’s posting rules was either odious, disquieting, or illegal. Their quarry was anything deemed inappropriate by the platform itself per its guidelines, which had been passed along to the contracting firm. Inappropriateness might be as mild a transgression as the insertion of a phone number or email address into a text field where it would be visible to another user, as this was a violation of rules that would allow participants to opt out of the platform and bypass its advertising and fee structure. Or it could be as serious as a reference to or even an image of child sexual abuse. The moderators had seen the full range.

During their shifts, the focus was on meeting metrics and moving quickly to review, edit, delete, resolve. The workers had just seconds to review and delete inappropriate material from user profiles. For people whose encounters with other cultures came largely via content screening, it was inevitable that some made judgments on those cultures based on the limited window that their work offered. As Sophia, one of the workers we were meeting, later told me, “It seems like all Europeans are sex maniacs and all Americans are crazy.”1

In the moment, there was little time to ruminate on the content they were removing. That activity was saved for later, when the moderators were off the clock and coming down from the intensity of a shift while gathered together around drinks.

It was at just such a point in the day that Andrew and I had scheduled to meet with the dating app mods. We walked further into the open-air shopping promenade to our appointed meeting place—a food court featuring a bustling outpost of the American restaurant chain TGI Friday’s and other similar Western fast casual chains. Young Manila urbanites crowded the tall outdoor patio tables, which were strewn with the trappings of youthful city dwellers everywhere: large-screen smartphones, cigarette packs, and IDs and proximity badges on lanyards personalized with small stuffed animals or buttons that had been casually tossed aside in a jumble, not to be needed until the following day. As we approached, more and more young people arrived, pulling up stools and joining conversations already in progress. Many had come from work in the nearby skyscrapers emblazoned with the logos of Citigroup and IBM, as well as other perhaps less familiar BPO multinationals like Convergys, Sykes, and MicroSourcing. Servers hurriedly circled the tables, rushing to take drink and appetizer orders, bringing large draft beers and colorful, umbrella-festooned cocktails to the growing throng of workers celebrating quitting time.

The sun continued on its upward trajectory across the morning sky and radiated its heat down upon us. Elsewhere, the North American business day drew to a close. All Europe was under night’s dark cover. But in Manila, drinks were arriving at the end of the workday. It was 7:00 a.m.: happy hour in Eastwood City.

We eschewed the happy hour scene at the TGI Friday’s and other eateries in favor of the relative tranquility of an international coffee chain. While the commercial content moderation workers we were destined to meet were just coming off their shifts in one of the nearby high rises, we were just starting our day, and the coffee was welcome.

We took our seats and waited for our interviewees to arrive, having given them rough descriptions of ourselves. Business at the café was bustling. Most everyone in line was wearing the international symbol of office workers everywhere: a proximity access card and employee badge. They were overwhelmingly young and female. At the start of each new transaction, the café employees welcomed the customers in English with “Hi, how are you?” or “Hi, what can I get for you?” before finishing the transaction in Tagalog, ending with a singsong “thank you!” once again in English. Smooth American jazz played in the background, vibes and sax the backdrop to the lively conversations taking place among clusters of office workers. Of course, as the only obvious non-local and White Westerners in the café, we knew we stood out well enough that the workers who had agreed to meet with us would find us without trouble.

They each filtered at their own pace near 7:00 (6:00 a.m. was their quitting time), joining us and exchanging greetings. The workers, who all knew each other, and had all been in touch with us prior to our meeting, had connected to us via a peer in the business process outsourcing, or BPO, community. We had been in contact with that source, who was an outspoken community leader and popular with many call center workers in the Manila area. He had forwarded our request to meet up with Manila-based professional moderators through his large network of BPO employees, and this group of five had agreed to join us. In return for their willingness to share with us, we promised to disguise their names and key features about them, including specific locations and names of where they worked and other identifying details. As with all workers who have shared their stories in this book, their names and other details should be therefore considered pseudonymous.

The BPO employees who joined us that morning were four men and one woman. Sofia de Leon was twenty-two, the youngest of the group. She was followed in age by R. M. Cortez, twenty-three, and John Ocampo, twenty-four. Clark Enriquez was twenty-six, and the eldest, Drake Pineda, was twenty-nine. Drake was also the only one who no longer lived with his parents and extended family; he was soon to be married and planning for a family of his own. The other four still lived with parents and were responsible, at least in part, for supporting their families financially. We started our conversation there, with their families’ perceptions about the work they did as moderators in a BPO setting.

STR: How do your families feel about BPO work?

Drake Pineda: It’s okay. It’s okay with them.

Clark Enriquez: As long as you get paid.

John Ocampo: As long as you make a contribution, it’s not an issue.

STR: You contribute to your family?

John Ocampo: Actually, they think if you work in the BPO industry you will have a higher-paying salary. They thought that, because it’s working a white-collar job . . . call center is like white-collar job.

Each of the moderators we met with worked for the same firm: an American company I call Douglas Staffing that has its major call center operations and the majority of its employees in the Philippines. While BPO firms in the Philippines have more typically been associated with live call center telephone work, such as service calls, customer support, sales, and technical support (referred to as “voice accounts” by many BPO employees), each of these workers was engaged solely in providing commercial content moderation services to a company that Douglas Staffing had contracted with. At Douglas, the workers were assigned to a specific account: the dating app I will call LoveLink.

Sofia, in her second year as a BPO-based commercial content moderator, was the first to describe the trajectory that led her to Douglas and the LoveLink product:

I started working last year because it was my first job after graduating. I rested for three months, then I applied for a job. Actually, it’s my final interview with another company, but Douglas pulled me to attend this, uh, initial interview. Then I applied for a voice account, but sadly, unfortunately, I didn’t pass. Then they offered me this, uh, non-voice. I didn’t have any [knowledge] about my job because it was my first time, then I passed the initial interview, then they gave me a schedule for a final interview. Then the interviewer said, “Tell me about yourself.” “I know how to edit [photos], like cropping. Then the shortcut keys, they asked me what different shortcut keys I knew. Then there was a logic example, also: “Find the difference in the different photos.” Then, luckily, I passed the final interview; they offered me the job offer and contract, within the day, one-day process. Then, they told me it’s a dating site. I’m excited, it’s a dating site, I can find a date! Then we went through, next thing, then it’s actually probationary, it’s actually for six months. And then we became a regular employee. Then, we became a regular employee of last year.

Twenty-four-year-old John Ocampo had been hired at the same time as Sofia, when Douglas, early in its contract, was greatly expanding its team dedicated to moderating LoveLink. Sofia described John and herself as “pioneers,” in reference to their two-year tenure on the job and on LoveLink, specifically. Like Sofia, he had initially applied to be on the phones, answering calls in real time from customers primarily from North America. A recent college graduate, he had prepared for another career but changed gears and sought employment instead in the BPO industry. He described this decision as a pragmatic one based on financial opportunity and job availability: “Actually, I’m a graduate of HRM, hotel and restaurant management, but I chose to work in the BPO industry, because at that time, the BPO was a fast-moving industry here in the Philippines. Better chance for employment and more competitive salary. So I chose to apply for the BPO industry. And I also applied for voice first, but because of the lack of knowledge about BPO I failed many times, but I did try.”

Like Sofia and R. M., as well, John arrived at commercial content moderation as a sort of consolation prize for having failed the employment examination that Douglas administered to potential workers hoping to get a position on live calls. In some aspect of that process—whether their ability to think on their feet, to speak in colloquial, Americanized English, or some combination of the two—their skills were deemed insufficient, and they were relegated to the commercial content moderation work that Douglas also undertook. In the world of Filipino BPOs, or certainly at Douglas, non-voice moderation was seen as a second-tier activity.

All five employees we met with were charged with reviewing and moderating profiles on LoveLink. Each time a user of the site or app changed anything about his or her user profile, the edit would generate a ticket that would then be reviewed by a worker like those we spoke with, to approve or deny. This included the uploading or editing of photos, a change in status, or any text the user might wish to include. Because the edits need to be approved before the profile can go live, workers were under constant pressure to act quickly. But that was not the only reason for speed. The employees reported a constant sense, and threat, of metrics by which their productivity was rated. Drake Pineda described the overall metrics process, with assistance from his peers.

Drake Pineda: The metrics is all about the . . . how many tickets we process. It’s like every profile, we do some filtering. There’s a lot of tickets, it’s like about 1,000 every day. We have a quota, it’s like 150 [tickets] per hour.

Sofia de Leon: Before it was 100.

STR: Oh, they raised it.

Drake Pineda: Because of the competitor, so 150 tickets per hour, so that makes it 150 but you do it at 200 . . .

Sofia: 150 to 300 [tickets per hour].

Productivity metrics were also measured based on length of processing per ticket, which John Ocampo described: “They have a standard like, first you have to handle the tickets for thirty-two seconds. But they, because of the increase in volume, because of the production, they have to cut it for less than fifteen to ten seconds.”

In other words, over the time that Douglas Staffing had employed Sofia and her colleagues working on LoveLink, the expectation for their productivity in terms of handling tickets had effectively doubled. Although they had at one time had over thirty seconds to review and evaluate a change or an edit vis-à-vis the site’s policies and guidelines, that time was now halved, meaning that the result would be a doubling of the number of tickets processed—without a commensurate pay increase.

The logic offered by the management for the increased demand in their productivity was that these increases in worker productivity were required to retain “the contract.” The workers and their managers were referring to Douglas Staffing’s deal to undertake commercial content moderation on behalf of LoveLink; “the contract” was both the arrangement with LoveLink, in particular, as well as a reference to keeping the commercial content moderation work in the Philippines, more generally. For all of the workers we spoke to that day in Manila, the specter of the contract disappearing to a lower-bid, higher-productivity site outside the Philippines was omnipresent. As evidence of this possibility, Clark Enriquez gave us a picture of the raw employment numbers for the LoveLink team.

STR: How many colleagues do you have right now?

Clark Enriquez: Before we reached 105 [commercial content moderation employees on the LoveLink product], but now we’re only 24.

STR: Oh, did you lose some?

Clark Enriquez: We lose [them] to other vendors.

This same competitor, the “other vendor” mentioned as being responsible for the increase in productivity metrics, was identified by the whole team as being of Indian origin. Whether or not this was true, it mattered that the team saw India as a primary competitor, as they were induced to work harder, faster, and for less because of the constant fear of Douglas losing its CCM contract with LoveLink to a lower, possibly Indian, BPO bid.

John Ocampo: Ultimately, our competitors [are] from India. They were, like, bargaining, so because it’s not voice [but commercial content moderation work], so it’s . . . they just go for Indian salary. Here in the Philippines we have a standard [of pay], so they go to the cheapest.

STR: They go to the cheapest contract, right?

John Ocampo: They are the cheapest.

The Philippines and Commercial Content Moderation as Infrastructure

The commercial content moderation workers from Metro Manila that I spoke to in the summer of 2015 were right to be concerned about India as a site of competition for BPO-based commercial content moderation work. There has been a race for the Philippines to move ahead of India as the world’s call center of choice, and it achieved this goal in recent years, emerging as the BPO—or call center—capital of the world, surpassing India despite having only one-tenth of the latter’s population.2 But that position is constantly being challenged as other regions and nations compete to solicit the world’s service-sector and knowledge work. To facilitate the Philippines’ ranking as the world’s chief offshoring/outsourcing employment center, substantial infrastructure improvements have been made, particularly since the late 1990s, to support the flow of data and information in and out of the archipelago.

Such accommodations have included significant geospatial and geopolitical reconfigurations, particularly since the 1990s. Public-private partnerships between agencies of the Filipino government, such as PEZA (the Philippine Economic Zone Authority), along with private development firms and their access to huge amounts of capital, have transformed contemporary greater Manila and areas across the Philippines into a series of special economic zones (colloquially known as “ecozones”) and information technology parks: privatized islands of skyscrapers networked with fiber-optic cables, luxury shopping districts, and global headquarters of transnational firms, incongruously within a megalopolis where brownouts are commonplace.3

Building off the critical infrastructure turn in digital media studies, I want to provide further context for the digital labor in the Philippines (with particular emphasis on commercial content moderation) to make the connection between the Philippines as a global labor center and the infrastructure—physical, technological, political, sociocultural, and historical—that exists to support it.4 The cases of Eastwood City, the Philippines’ first designated information technology park ecozone, owned and developed by Megaworld Corporation, and the Bonifacio Global City, or BGC, an erstwhile military base, will be explored, all contextualized by discussion of the Philippines’ colonial past and its postcolonial contemporary realities.5

The intertwined functions of “infrastructure” at multiple levels respond to Lisa Parks and Nicole Starosielski’s statement that “approaching infrastructure across different scales involves shifting away from thinking about infrastructures solely as centrally organized, large-scale technical systems and recognizing them as part of multivalent sociotechnical relations.”6 This approach opens up the analysis of “infrastructure” to include the systems traditionally invoked in these analyses (electrical, water, communications, transportation, and so on) but also the other aspects of infrastructure—in this case, policy regimes and labor—that are key to the functioning of the system as a whole and yet have often either been treated in isolation or given less attention in the context of “infrastructure.”

Parks and Starosielski urge us to look to labor not in isolation but as a primary component of infrastructure’s materiality: “A focus on infrastructure brings into relief the unique materialities of media distribution—the resources, technologies, labor, and relations that are required to shape, energize, and sustain the distribution of audiovisual signal traffic on global, national, and local scales. Infrastructures encompass hardware and software, spectacular installations and imperceptible processes, synthetic objects and human personnel, rural and urban environments.”7 Their work is consistent with that of scholars like Mél Hogan and Tamara Shepherd, who also foreground the material and environmental dimensions of technological platforms and those who labor to make them.8 In the Philippines, the availability of legions of young, educated workers fluent or conversant, culturally and linguistically, in North American colloquial English has been one major aspect of the country’s rise in BPO work emanating from the United States and Canada. But vast infrastructure developments and policy initiatives of other kinds, including historical relationships of military, economic, and cultural dominance, have also led to this flow of labor from the Global North to the Global South.

The Filipino Commercial Content Moderation Labor Context: Urbanization, Special Economic Zones, and Cyberparks

Metro Manila comprises seventeen individual cities or municipalities, each governed independently, and a population of almost thirteen million as of 2015, making it one of the most densely populated places on earth.9 The area’s growth in population and its infrastructure development over the past decades are tied directly to the country’s rise as a service-sector center for much of the (primarily English-speaking) West. Its development has been uneven as major firms locate important branches and business operations there, taking advantage of an abundant, relatively inexpensive labor force already intimately familiar, through more than a century of political, military, and cultural domination by the United States, with American norms, practices, and culture.

The availability of this type of labor force goes hand-in-hand with the service-sector work being relocated to the Philippines, which calls on linguistic and cultural competencies of workers, on the one hand, and immense infrastructural requirements (such as uninterrupted electricity, the capacity for large-scale bandwidth for data transfer, and so on) created and maintained by private industry for its own needs. These infrastructural developments are facilitated and supported by favorable governmental policy regimes that offer immense incentive to developers and corporations alike. Urban planning scholar Gavin Shatkin describes the case:

One defining characteristic of contemporary urban development [in Metro Manila] is the unprecedented privatization of urban and regional planning. A handful of large property developers have assumed new planning powers and have developed visions for metro-scale development in the wake of the retreat of government from city building and the consequent deterioration of the urban environment. They have developed geographically “diversified” portfolios of integrated urban megaprojects, and play a growing role in mass transit and other infrastructures that connect these developments to the city and region. This form of urban development reflects the imperative of the private sector to seek opportunities for profit by cutting through the congested and decaying spaces of the “public city” to allow for the freer flow of people and capital, and to implant spaces for new forms of production and consumption into the urban fabric. I therefore term this “bypass-implant urbanism.”10

Although a World Bank report from 2016 on East Asia’s urban transformation stated that “urbanization is a key process in ending extreme poverty and boosting shared prosperity,” the process under way in Metro Manila reflects an unevenness, fragmentation, and expropriation of infrastructure and resources that appear to be in the process of undergirding the stratification of and disparity in wealth and property distribution in that region.11 According to Shatkin, the case of Manila “is not merely a consequence of the blind adoption of ‘Western’ planning models,” but something more complex and particular to “the incentives, constraints, and opportunities presented by the globalization of the Philippine economy, which has fostered a state of perpetual fiscal and political crisis in government while also creating new economic opportunity in Metro Manila.”12

The urbanization process of interest to Shatkin, as well as the new economic opportunity for a handful of developers and for global capital, can be linked directly to the governmental policy regimes and bodies that have administered these policies. Over the past four decades, a desire to move the Philippines onto the increasingly globalized stage for certain industries by attracting transnational corporations through favorable policies has led to an increasing reliance on private industry for investment in that development. The Export Processing Zone Authority, or EPZA, was the first agency to establish modern economic zones, the first of which was in Bataan 1969. It functioned under

the traditional model where [such zones] are essentially enclaves outside of the country’s “normal customs territory” with production of locator firms being meant almost entirely for the export market and with their intermediate and capital inputs being allowed to come in free of duty and exchange controls. To encourage investment, the zones were aimed at providing better on-site and off-site infrastructure, and locators were also granted fiscal incentives. As in other countries, the EPZs were created with the following objectives: (i) to promote exports, (ii) to create employment, and (iii) to encourage investments, particularly foreign investments.13

From the development of these first export processing zones in the late 1960s through 1994, a total of sixteen such zones were established throughout the archipelago.14 Republic Act 7916, otherwise known as the Special Economic Zone Act of 1995, paved the way for a new body, the Philippine Economic Zone Authority (PEZA), to take over the functions of the former Export Processing Zone Authority (EPZA) in 1995. This investment promotion agency is attached to the Philippine Department of Trade and Industry. The greatest shift from the EPZA’s first-wave model to PEZA’s second generation was the transferring of the development of the ecozones from the government to private concerns: “The State recognizes the indispensable role of the private sector, encourages private enterprise, and provides incentives to needed investments.”15

There are special economic zones, or ecozones, for tourism, medical tourism, and manufacturing, in addition to information technology. The information technology sector was created through legislation in 1995. Megaworld Corporation, founded by Chinese-Filipino billionaire Andrew Tan in 1989, developed Eastwood City Cyberpark, and in 1999 it became the first IT park in the Philippines to be designated a PEZA special economic zone, via Proclamation 191.16 As described on Megaworld’s website:

Eastwood City is a mixed-use project on approximately 18 hectares of land in Quezon City, Metro Manila that integrates corporate, residential, education/training, leisure and entertainment components. In response to growing demand for office space with infrastructure capable of supporting IT-based operations such as high-speed telecommunications facilities, 24-hour uninterruptible power supply and computer security, the Company launched the Eastwood City Cyberpark, the Philippines’ first IT park, within Eastwood City in 1997. The Eastwood City Cyberpark includes the headquarters of IBM Philippines and Citibank’s credit card and data center operations as anchor tenants. In connection with the development of the Cyberpark, the Company was instrumental in working with the Philippine Government to obtain the first PEZA-designated special economic zone status for an IT park in 1999. A PEZA special economic zone designation confers certain tax incentives such as an income tax holiday of four to six years and other tax exemptions upon businesses that are located within the zone. The planning of Eastwood City adopts an integrated approach to urban planning, with an emphasis on the development of the Eastwood City Cyberpark to provide offices with the infrastructure such as high-speed telecommunications and 24-hour uninterrupted power supply to support BPO and other technology-driven businesses, and to provide education/training, restaurants, leisure and retail facilities and residences to complement Eastwood City Cyberpark.17

In other words, these ecozones operate with special dispensation from taxation, more favorable rules on business practices, such as importing and exporting of goods, as well as with a highly developed and typically totally privatized infrastructure, separate from what is available in other areas of Manila and greatly improved. They are frequently the location for the global or regional headquarters of transnational firms that rely on both the infrastructure and the local labor market that flows in and out of the ecozone each day.

Finally, these ecozones provide housing, shopping, and entertainment for those who can afford the steep prices charged for the real estate and lifestyle they offer their denizens.

The workers themselves who circulate in and out of the cyberparks and ecozones are not typically able to partake in all of their splendor. The commercial content moderation workers we spoke to earned roughly four hundred dollars a month, and were responsible for supporting their families, in part, on that income. The workers described this rate of pay as less than one might earn on a comparable voice account, in which agents would be taking live calls in a call center rather than adjudicating user-generated content. Yet the salaries they were earning at Douglas, working on LoveLink, were ones they considered on the high end for commercial content moderation work alone.

John Ocampo: We’re just looking for the salary, cause for a non-voice account [what Douglas pays is] pretty big.

STR: Is a non-voice account usually less than a voice account?

John Ocampo: Yes, a bit less . . .

Drake Pineda: It depends on the account.

STR: And does it depend on the company too?

Sofia de Leon: Yes.

STR: Can you give us any idea of what that might be?

John Ocampo: It’s around 20,000 [Philippine pesos per month] . . . below.

Andrew Dicks: And voice account would be?

Drake Pineda: Sometimes like a 1,000 [Philippine pesos per month] difference.

Of the five workers we spoke to, Drake was in the best position to attest to this difference in pay: he had come to commercial content moderation work at Douglas after several years of having been on BPO voice contracts. He had suffered what he described as “burnout” after years of fielding hostile and abusive calls from American customers, often angry at the fact that they were speaking to someone with a non–North American accent. Taking the pay cut to be off the phones was a bargain he was willing to make.

Bonifacio Global City

Several scholars have identified the impact of neoliberal economic planning on urban infrastructure development, and on that of the Philippines in particular.18 Some of these cases are examples of entire cities and urban spaces being created out of whole cloth to attract and serve global economic concerns, with emphasis on the infrastructure needs of transnational corporations running on a 24/7 global cycle. Further, Parks and Starosielski have described “how an established node can be used to generate new markets and economic potentials.”19 Today’s Bonifacio Global City, or BGC, in Manila is one such case.

The military encampment formerly known as Fort Bonifacio, used in succession by the Spanish and American colonial occupiers, was given over to the Philippine military before being transformed, more recently and seamlessly, into another “global city.” A website dedicated to business development in the BGC waxes poetic about the transformation.

Bonifacio Global City was once part of a multi-hectare portion of Taguig that the United States government acquired in 1902 and operated as a military base. Christened Fort McKinley after U.S. President William McKinley, it was the headquarters of the Philippine Scouts, the Philippine Division of the United States Army. In 1949, three years after the Philippines gained political independence from the United States, Fort McKinley was turned over to the Philippine government. In 1957, it was made the permanent headquarters of the Philippine Army and renamed Fort Bonifacio after Andres Bonifacio, the Father of the Philippine Revolution against Spain. In the 1990s approximately 240-hectares of Fort Bonifacio was turned over to the Bases Conversion Development Authority (BCDA) to facilitate the conversion of former U.S. military bases and Metro Manila camps into productive civilian use. By 2003, Ayala Land, Inc. and Evergreen Holdings, Inc. entered into a landmark partnership with BCDA to help shape and develop Bonifacio Global City—an area once synonymous with war and aggression—into the amiable, nurturing, world-class business and residential center it is today.20

Today BGC is home to numerous multinational business headquarters, retail outlets, and entertainment and dining locations. It is upscale, glittering, and always under construction. It is also the site of several BPO firms involved in the commercial content moderation industry, including the headquarters of MicroSourcing, the BPO firm we met earlier offering “virtual captives” available to provide a ready-made and easily disassembled labor force of commercial content moderation specialists comfortable with colloquial American English, as their North American clients require.

A street corner in Bonifacio Global City in May 2015; a Mini auto dealership is on the street-level corner, and several offices of BPOs, including those engaged in commercial content moderation and serving clients from around the world, are nearby.

In Metro Manila, the new and large urban development projects, such as Eastwood City and BGC, attract labor from the impoverished rural peripheries, and these workers in turn create new urban markets for labor, goods, and services, generating a need for more infrastructure and resulting in more uneven development. A new self-contained development, such as Eastwood City, may appear to have its infrastructure needs met, yet the surrounding ripple effect of lack of development often means that areas adjacent to the glimmering ecozones suffer from an acute lack of infrastructure, including power brownouts and inadequate grid support, a paucity of housing and street space, and so on.

But it is not even just the tangible disruptions at play when a location gives itself over to a development and business cycle dictated by nations and economies far afield. Labor scholar Ursula Huws describes what happens to cities and their populations under such demands: “The traditional diurnal rhythms of life are disrupted by requirements to respond to global demands. The interpenetration of time zones leads inexorably to the development of a 24-hour economy as people who are forced to work nontraditional hours then need to satisfy their needs as consumers during abnormal times, which in turn obliges another group to be on duty to provide these services, ratcheting up a process whereby opening hours are slowly extended right across the economy, and with them the expectation that it is normal for everything to be always open.”21

Such is absolutely the case with Metro Manila’s ecozones and the areas surrounding them built up, now, to support them. The happy hours at 7:00 a.m. are emblematic of a real-life day-for-night in which the prime economic engine of the BPO firms come online once the sun has gone down, and the rest of the city, and a nation, follows suit.

Postcolonial Legacies, BPOs, and the Philippines

In her doctoral dissertation on the Filipino BPO industry, Jan Padios in 2012 described the shift of customer service call centers from the Global North to the Global South, and to the Philippines in particular, as a process predicated fundamentally on historical colonial domination of the Philippines by the United States and a continued economic and cultural relationship of dominance in the era since U.S. official political control has ended. Her book A Nation on the Line: Call Centers as Postcolonial Predicaments in the Philippines is an important update to this work.22

Padios writes, “Filipinos have been ‘socialized’ to speak American English and cultivate affinity for American culture as a result of U.S. occupation of the Philippines and its postcolonial legacy. . . . Many Filipinos have, in other words, developed an intimacy with America—an intimacy fraught with much tension and abjection—this is constructed as the cultural value that Filipinos bring to call center work.”23 Padios furthers her theoretical framing of what she describes as “productive intimacy”: “Productive intimacy is the form that close relationships take when they are made productive for capital; when used as a form of corporate biopower, productive intimacy allows capital to govern workers from within their relationships, putting their affective attachments to use in the creation of exchange value and surplus value.”24 It is this interpersonal and intercultural intimacy upon which the transnational BPO market, and particularly those firms offering commercial content moderation, seek to capitalize by monetizing Filipino people’s proximity to American culture, largely due to decades of military and economic domination, and selling it as a service. The evidence is in the ad copy of MicroSourcing’s solicitations, but MicroSourcing is far from the only firm that sells Filipino labor to Western markets in this way.

Indeed, this value-added aspect of the Filipino BPO for the North American commercial content moderation market is well understood; doing moderation work outside one’s spoken language of choice and everyday cultural context is extremely difficult and presents novel and distinct challenges, so any mechanism that provides increased skill (or perception thereof) in these areas can be operationalized by firms in the industry. As John Ocampo confided, “Before [doing professional moderation work] we didn’t have any idea about [American] racial slurs.” Yet the Douglas contractors for LoveLink had become quick studies in the array of racial denigration that its North American users might employ in their dating profiles, and, after all, they had the internet and its vast tools to use when deciding whether to allow a particular turn of phrase in a user profile or not. “Actually,” Clark Enriquez exclaimed, when encountering potentially racist insults or descriptions, “we can go to Urban Dictionary” to look them up. “Sometimes,” Andrew and I confessed, “we have to do that, too.”

For the Western firms in need of commercial content moderation work who choose to outsource, there is an additional appeal. Just as in the textile and manufacturing sectors (such as Apple contracting with Foxconn, or H&M with various contract textile manufacturers in Bangladesh), creating layers of contractors between the firm where the work originates and the ones that actually carry it out lends plausible deniability when there are repercussions for this work. When a commercial content moderation worker finds himself distraught over the uploaded content he views every day in his employment, he is typically precluded by geography, jurisdiction, and bureaucratic organization from taking any complaints directly to Facebook, Google, Microsoft, or any of the major tech or social media firms his work ultimately benefits. In utilizing offshore contracting firms, companies that outsource their commercial content moderation put it, quite simply, out of sight and out of mind. Although the workers we met supported LoveLink’s product and, by extension, the company that owned it, it was unlikely that anyone at LoveLink would think of the people doing moderation at Douglas Staffing as their employees, if they thought of them at all. Indeed, that disconnect and uneven dynamic was by design.

At the turn of the millennium, sociologist Manuel Castells famously theorized the “Network Society,” an information-driven economy characterized by the compression of time and space into a “space of flows” and organization and labor practices reconstituted into flexible, reconfigurable, and dynamic structures that more closely resembled interconnected nodes than they did the top-down hierarchies of the factories and plants of the industrial era.25 Such organization, enhanced by the digitized, data-driven computational power of global informational connectivity, transcended geospatial boundaries into global networking arrangements and was no longer limited to a traditional work day, but could function across time zones and around the clock. Yet this seeming rupture with traditional hierarchies and relationships has not proved to be as radical or liberatory as portended almost thirty years ago, as it has been taken up in the service of other political and economic ideologies. Instead, we see acceleration and flexibility of work and worksites, a phenomenon many scholars, such as David Harvey, decry as quintessentially neoliberal in nature, of benefit almost solely to employers and corporate interests.26 And the trajectory of the “flow” looks very similar to well-worn circuits established during periods of formal colonial domination and continuing now, via mechanisms and processes that reify those circuits through economic, rather than political or military, means.

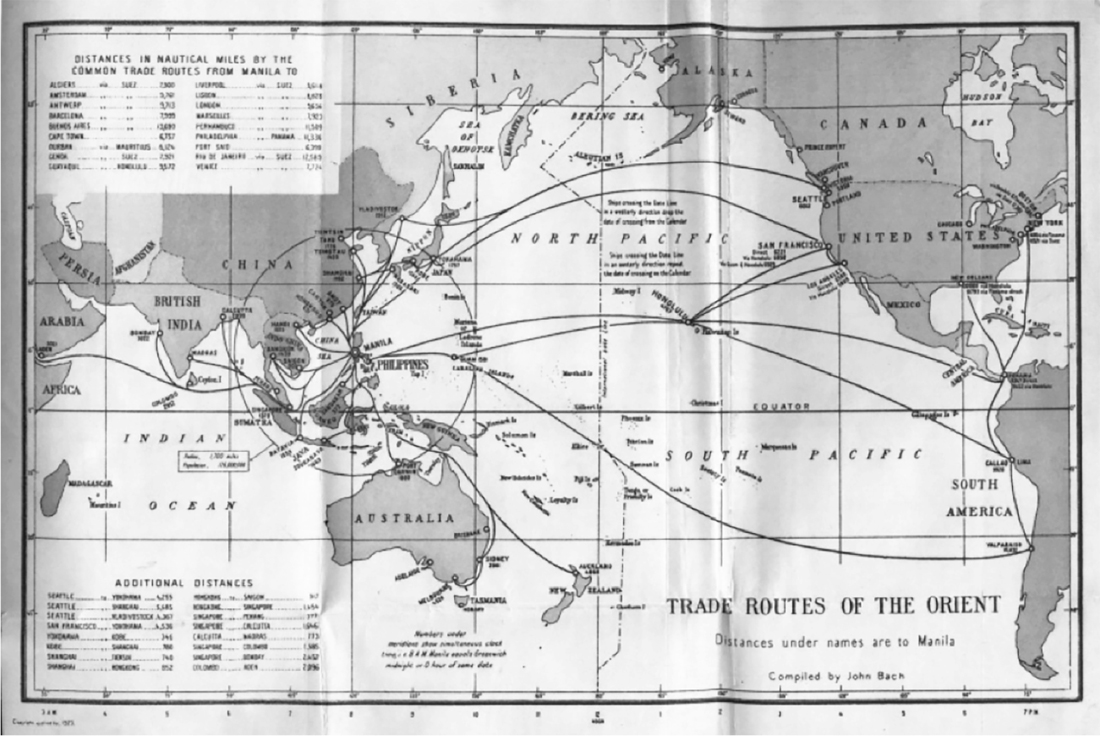

“Trade Routes of the Orient,” from Beautiful Philippines: A Handbook of General Information, 1923. (Courtesy of the Newberry Library)

“Eastwood City’s Modern Heroes”

After our meeting with the five Douglas Staffing commercial content moderators, Andrew and I decided to explore the Eastwood City information technology park a bit more on our own. We saw many North American and international chains, such as the Coffee Bean & Tea Leaf and the Japanese fast-fashion store Uniqlo, among the gardens, fountains, and walkways of the ecozone. We wandered through the open-air mall as workers hosed down the foliage and repaired the tiles of the plazas and pathways. As the early morning hours ceded to a more reasonable time for families and older people not on the BPO clock to make their way into the area for shopping or dining, the plazas began to fill up with people meandering through the space in large, intergenerational family groups or in smaller groups of young people together, often arm-in-arm, shopping bags in tow.

Despite having never been to Eastwood City before, I was seeking out one particular feature. I was aware that there was a statue placed there, a sort of manifestation of banal corporate art that most people probably did not pay a great deal of attention to under ordinary circumstances. The statue, I understood, was dedicated to the workers who labored in the BPO sector. I was hoping to see it for myself.

As we walked in the direction that I made my best guess it might be in, Sofia and John came striding up. They had decided to stay at Eastwood City after our interview and do some sightseeing of their own. Where were we headed, they asked? When I described to them the statue I was seeking, they knew immediately what I was talking about, and invited us to follow them directly to it.

The statue was one of many elaborate corporate artwork installations that decorated the ecozone. Some were fountains decorated with a variety of motifs and ornate; others were lifelike bronzes of family dogs. But this one was special—quite large, with a round pedestal that filled up a central portion of the plaza where it stood. On its base was a plaque that read:

This sculpture is dedicated to the men and women that have found purpose and passion in the business process outsourcing industry. Their commitment to service is the lifeblood of Eastwood City, the birthplace of BPO in the Philippines. Eastwood City was declared under Presidential Proclamation No. 191 as the Philippines’ first special economic zone dedicated to information technology. EASTWOOD CITY’S MODERN HEROES

I stood in front of the looming statue, endeavoring to capture it from several angles, so that the different people it represented—a woman seated at a desk, a man carrying a briefcase and a book and in a dynamic pose, another woman also seemingly frozen in movement, with a ledger under her arm—all would be featured in one photo or the other. The statue was large enough so that getting each figure in detail was difficult without the multiple shots. I noticed while I was going through my photo shoot that some of the shoppers and visitors to Eastwood City, as well as the crew replacing tile nearby, seemed to notice my interest in the statue and found it odd, as if to say, “You know that’s just cheesy corporate art, right?” or perhaps, “We have art museums in Manila if you want to go there to check them out.” It made me self-conscious, as it probably seemed silly to give so much attention to what most would walk right past.

A statue in Eastwood City, Manila, commemorating the Philippines’ BPO workers, which it describes as “modern heroes.”

The statue towered over the plaza, three figures, oversized and fashioned out of metal in business casual attire. Each of the three figures of the statue was faceless, Eastwood City’s everyman and everywoman, but, importantly, each one wore a headset signifying his or her role as a voice on the other end of the line. The reference to “modern heroes,” too, was important: the Filipinos who had left the archipelago to work abroad throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries—collectively known as Overseas Filipino Workers, or OFW—were often referred to by the Filipino government and media as “new heroes.” Here were the modern ones who could now work abroad while staying at home—from the call center.27 The statue needed some updating, I thought, to represent the newer labor forms taking hold in the BPOs in Eastwood City and in other areas throughout Manila just like it. But how would an artist depict the work of commercial content moderation? The statues would likely be faceless, just like these, but no headsets would be needed. The work was cognitive—purely mental—and the challenge to the artist would be to depict the trajectory from the moderator’s mind to the action of a click to delete or skip. Perhaps, even more difficult, the artist would have to find a way to demonstrate absence in a bronze. Would they depict the excessive drinking? Could they find a way to show the moderator insulating herself from friends and family? Or suffering a flashback from an image seen on the job? For now, the traditional phone workers and voice account representatives of the BPOs would have to suffice as stand-ins.

After I got my photos of the statue, Sofia and John surprised me by asking for a favor. Each one handed me a Samsung smartphone and asked me to take a snapshot of them together as they stood in front of the statue. They smiled into the camera as I pointed, clicked, and heard the electronic reproduction of a camera shutter. In this way, even for just a moment, commercial content moderators were represented alongside the better known BPO workers present in the plaza. We said our goodbyes after that and went our separate ways, the two of them flowing back into the growing crowds of shoppers and passersby until they disappeared completely from our view.