2: Why There Are Males -- Men are humanity’s essential genetic design and test lab

“Almost everything I ever did, even as a scientist, was in the hope of meeting a pretty girl.”

James D. Watson, Nobel Laureate, author The Double Helix.

The sexes solve the problem sex itself failed to solve

The essential difference between a man and a woman? It’s tied up with the mystery of sex.

Correction: the mystery of why there is such a thing as sex, in rough outline we know, and have known for some time. The real mystery is why we have the sexes. To understand the real root of sex difference, this has to be grasped; so what follows is an exposition - in as plain a language as possible - of the relevant science. The necessity for clarity and straightforwardness is bound to come across as a tad dry and didactic, but please do persevere, as you should find this focus worth it for the profound insight it leads to.

Just why are there males and females? After all, we could all be bisexual (hermaphrodites) - individuals each with both sets of sex organs, male and female. (On account of the primary association of the word ‘bisexual’ with sexual orientation, from now on I will use the term ‘bi-sexed’). As long as we had sex with each other rather than with ourselves, then this would be perfectly valid sex according to what, supposedly, sex is for. This is the random swapping of all the genes between any and every two individuals when their mating makes offspring, so that all the genes in the gene pool get well mixed; thereby stopping us genetically getting set in our ways. It helps avoid a collective trip down some evolutionary blind alley, leading to eventual extinction. The point is that to achieve this, you don’t need everyone to have only either the one or the other type of sex organs; male or female. Penises and vaginas don’t need to be segregated between individuals.

We are not all bi-sexed for a very good reason, but before I can give you the reason - for it to make sense to you - I first have to explain a little more the essence of why there is such a thing as sex.

For a long time in the history of biological evolution there was no sex at all. All individuals of all species were asexual reproducers, making simple duplicate copies of themselves, Xerox fashion. This was fine for simple creatures with simple genomes, because when they produced copies of themselves not much could go wrong. Even if it did, parthenogenesis (as asexual reproduction is called) is cheap, and the extended families of now unviable individuals could simply go to the wall. Quite a number of these dead-end lineages could bite the dust and the local population would just get on with it. But as new species evolved that had ever more complex genetic make-ups, this had to change, because their complexity meant that replication could turn out wrong in a vastly expanded range of ways. And the more sophisticated the genome, the more expensive they are to produce, and therefore the fewer of them there are. Consequently, allowing whole lineages to die was just too costly. So it was that sex arrived on the scene - and sure enough, at first these sexual species were hermaphrodites. Sex mixes up and dilutes genes damaged in replication (mutations), with the result that before they could do much damage to the reproducing group as a whole, they were lost from the gene pool. Or so it was supposed.

We now know that it was more complicated than that. The process of sex actually exacerbates the build-up of replication errors (Paland & Lynch, 2006). This is not least because whole lineages don’t die off as in asexual reproduction, but also because the repeated mixing up of genes in sex dilutes any ‘dodgy’ genes, and then in their pairing up on chromosomes as alleles - two copies of the same gene that are not necessarily the same - defective genes can be hidden through being the ‘recessive’ (unexpressed) half of the gene pairing. The Xerox copy analogy of progressive degredation is more appropriate to describe sexual than asexual reproduction. Sex in itself still results in the genome in time accumulating malfunction to the point that it becomes unfeasible.

Paradoxically then, sex - the very process that evolved to deal with the problem of the building up of replication error - in itself actually contributes to this unwanted accumulation. How has Mother Nature solved this problem? By exploiting a consequence of the evolution of sex. Let me first explain this consequence and then how it was exploited.

Sex necessarily involves the fusion of two as yet undifferentiated cells (cells that have the potential to divide to make any cell type); one from each prospective parent, reserved for the purpose of sex. When sex first arrived on the evolutionary scene, these were identical; the gametes (as sex cells are called) were isogamous. There was no male and female because you could not tell them apart to so label them. Inevitably, though, ever so slight differences would emerge. One would be fractionally larger than the other: they became anisogamous. And once there was anisogamy, differences polarised, because there were advantages and disadvantages of being either the small or the large gamete that so-called ‘selfish DNA’ within the one or the other exploited to preserve the ‘interests’ of one gamete or the other after they fused in what is then called the zygote. The larger gamete took more energy to produce and so there were fewer of them, whereas the smaller gametes were relatively easy to make and consequently were made in larger numbers. The larger and consequently less-numerous gamete type represented a logjam in reproduction: the ‘limiting factor’ in the process. This necessarily places most selection pressure on the smaller gamete (Kodric-Brown & Brown, 1987; Parker et al., 1972).This logjam was thought to be the root of all the various sex differences we see across nature, and not least in men and women. So far as that goes, so it is. But a little more probing of this gets you to a much fuller explanation.

The smaller and more numerous gametes competed with each other to fuse with the rarer larger gametes. With the biological imperative always to reproduce as much as possible (within whatever constraints there were locally), the smaller, more numerous gametes became relatively disposable, and the larger gametes relatively more prized. As they polarised more and more, then this became an ever bigger problem.

It’s not just that as the larger gamete gets still larger there are consequently fewer of them, but that sex is an inherently expensive way for individuals to replace themselves and for the population of genes in the gene pool to try to expand itself. One small and one large gamete together make just the one offspring, whereas asexually they would make two: one each. Then there is the problem of the build-up of replication error that sex itself exacerbates.

These long-known problems of the extra cost of sexual (over asexual) reproduction and the accumulation of replication error, were then together solved by the process of evolution taking advantage of anisogamy in a simple way.

The ‘quarantining’ of both ‘good’ and ‘bad’ genes in the male

The solution is really quite an obvious exploitation of the difference between the gametes - which we can usefully distinguish by giving them labels: the smaller and the larger gametes are, respectively, male and female, of course.

If lots of deleterious replication errors build up across the population, then why not simply keep it away from the gamete type that is already holding up reproduction as it is? We don’t want females to be loaded down with genetic errors, that even if they don’t kill the females, either slow or stop them reproducing altogether. They are, as I said, the logjam in reproduction and need to be left to get on with the job. The less valuable males, on the other hand, could act as a sort of quarantine quarters for all of the genetic dead wood (Atmar, 1991). Sure enough, many males will as a consequence die, or be damaged to the point that they’re useless for reproduction; but they are in the majority or easier to produce in any case, so the population won’t be affected in the overall rate of reproduction. The adult males that produce the smaller gametes can produce so many that if need be, a very few adult males could supply all of the necessary gametes to fertilise all of the adult females in the local population; and then to fertilise all of the females again as soon as they have finished producing the batch of offspring from the first fertilisation.

What goes for the gametes also goes for the adults they produce. Male adults work as the locus of this process just as male gametes do. But because the male adults are much more exposed to the wider environment and for much longer than are the male gametes, then adults are by far the main vehicle for the process.

The problem is solved.

A wider problem is solved, actually. The ‘quarantining’ is not just for genetic dead wood earmarked for purging, but also for genetic material that is beneficial and worth hanging on to. Mutations and new gene combinations are not always injurious. Purging deleterious and retaining enhancing genetic material are respectively the negative and the positive parts of the same process that explains why sex, as well as the sexes, have evolved; or rather, why they have been retained as useful adaptations.

This explanation subsumes the various theories that challenged the original view that has held sway for nigh on a century: that sex was necessary to produce sufficient genetic variation. Debate has become complicated (Agrawal, 2006; Misevic, Ofria & Lenski, 2005; Otto & Gerstein, 2006; de Visser & Elena, 2007; Jaffe, 2002) but it had already resolved to a ‘pluralist’ approach (West et al., 1999; Birky, 1999); the theories all being related. Having not sex per se, but the sexes, equips the reproducing population not just to avoid sinking under the weight of its own accumulated gene-replication error, but to more quickly adjust to any changes in the environment and to thereby out-compete other lineages (and other species), thus avoiding extinction. For simplicity, I’ll refer just to the side of the process that gets rid of faulty genes; but please take it as read that I mean both the ‘negative’ (purging) and ‘positive’ (retaining) aspects.

Although the reproductive logjam may be the fundamental root cause of sex difference, it is the direct consequence of this ‘quarantining’ effect that is most illuminating of the sex differences we see in the more complicated organisms, not least in ourselves. So how is this ‘quarantining’ done? The problem is that if sex is random shuffling of genes, then it’s just pot luck which genes end up in male offspring, just as it is for female offspring.

To answer this question we need to get a little technical. I have been putting the word ‘quarantining’ in scare quotes, because I’ve been using it as shorthand for what generally happens. Yes, there are kinds of actual quarantining in some species; and this can be very marked in certain lowly animals. Plus there are other, more widespread, apparent instances that are as yet disputable - notably ‘achiasmate meiosis’ (Atmar, personal communication, 2007). These are beyond the scope of discussion here and I will instead stick with the bigger picture. More generally, the defective genetic material is indeed purged from the whole lineage through the male; but it’s not necessary to actually place the material in the male more than in the female. Instead, the material is either somehow expressed more in the male than in the female, or it’s expressed no more and no less than it is in the female but otherwise rendered much more exposed. I mean, of course, that genetic material is subject to natural selection. The result is the same as actual quarantining: the unwanted genetic material ends up in dead or non-reproducing (or less prolifically reproducing) males.

The male ‘filter’ at work

One way in which genetic material is more expressed in the male than in the female is by putting a lot of the more crucial genes in chromosomes that only pair up in females. Most chromosomes come in similar pairs, so that a single gene is made up of two alleles, with one on each chromosome. An allele may be either ‘dominant’ or ‘recessive’, and if the latter it will not be expressed (function) if it is paired with a ‘dominant’ partner. The sex chromosomes are different in that there are two very different types: X and Y. In females there are two Xs, but in males there is a single X (plus a Y). This means that genes that are ‘recessive’ and usually disguised in females through being paired with a ‘dominant’ counterpart gene or allele, in the male are instead naked, as it were. What they code for is actually expressed in the male, although unexpressed in the female. This means that natural selection will act much more on the genes of male sex chromosomes than it does on the genes of female sex chromosomes. The X chromosomes are by far the largest of the two sex chromosomes, and in the genomes of some species they may make up a quarter or a third of all genetic material.

The Y, whilst it may be considerably smaller, is peculiar to the male, so here we do have some actual quarantining of genetic material in the male. And very recent research has shown that there is far more, and more important, genetic material on the Y chromosome than had been thought. In more primitive species, it’s much bigger than it is in humans and other higher animals, so this quarantining evidently had more importance earlier in the evolutionary timescale.

What about the bulk of the chromosomes though? Those other than sex chromosomes - the autosomes - are the same in both males and females. If there is to be more exposure of genes in the male, then there will have to be some other way of doing this than having unpaired chromosomes peculiar to the male.

Enter the second way that males in effect quarantine genetic material without actually doing so: by rendering it more exposed. How? By males behaving differently to females so that they come up against the environment in all sorts of ways that lead to natural selection. If males can be driven to behave in ways that expose just how well-functioning or not are their genes, then natural selection will act more on males than on females, even though the sexes are equally likely to have some of the genes that the lineage needs to get shot of.

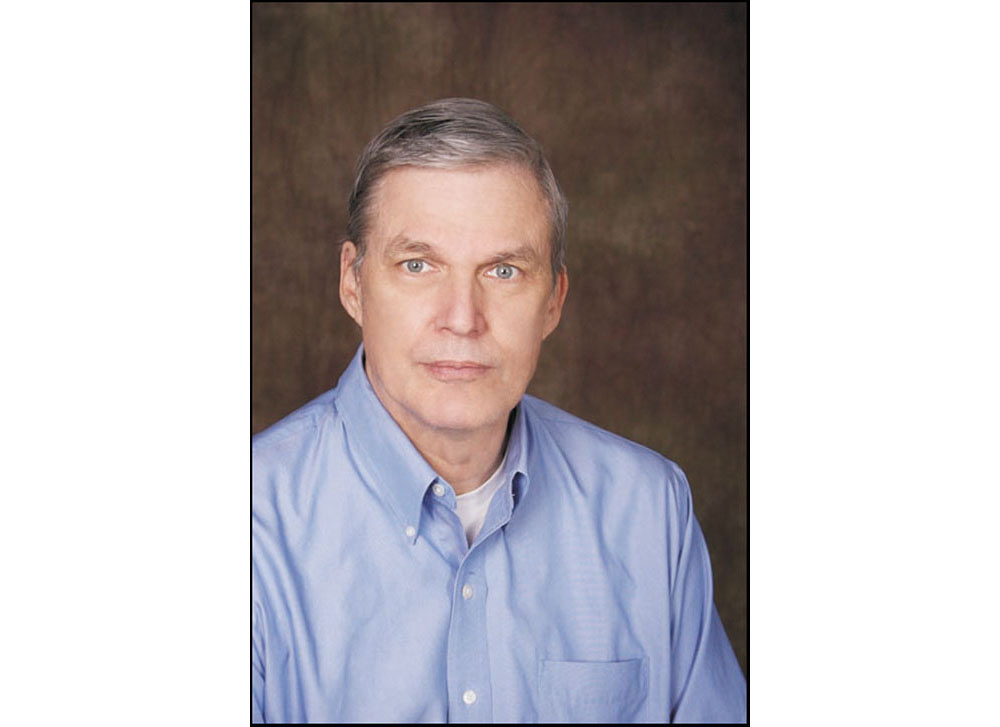

The father of the ‘genetic filter’

Wirt Atmar is the originator of the idea of a genetic ‘filter’, whereby males of most species in effect ‘quarantine’ deleterious genetic material away from females and eliminate it from the whole lineage (conversely allowing males to become the ‘laboratory’ for new genetic mutations or combinations). More narrowly conceived, it had occurred independently to several researchers over the years that something of this sort must be happening in species with an XX/X (denoted XX/XO) sex chromosome system (‘haplodiploidy’). Here the genes on the male’s single X chromosome necessarily are more exposed to natural selection than they would be in females with their pair. Atmar saw that a lesser but still very significant difference in exposure to natural selection would occur in common XX/XY sex chromosome systems, and then further realised that there were other mechanisms of effectively forcing more exposure to natural selection in the male of all genetic material; not just re genes on sex chromosomes. In particular, he recognised that the more vigorous and competitive behaviour of males was to this end.

Though he’s renowned as a computer engineering professor, Wirt Atmar has always also worked in biology research, showing that a fresh perspective from the world of man-made information processing proves useful in understanding the processing of biological code.

This contrast is evident in the gametes, which we know are subject to selection and much more so on the male (Lenormand & Dutheil, 2005; Jaffe, 2004). Compared to the single large egg lazily descending a woman’s fallopian tube just once a month, there are tens or hundreds of millions of sperm that a man ejaculates in a brief instant - possibly several times in just a single evening. Huge quantities of individual male sex cells then have to compete with each other as they negotiate the various stages of the female genital tract before in the end either none of them get near the egg, or one may be fortunate enough to actually attach itself to the egg and fuse with it. All of the others have fallen by the wayside and thereby taken what may be their (relatively) faulty genetic make-up with them.

Woody Allen experiences life as a male gamete in Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex (But Were Afraid to Ask), 1972

We all start and end as gametes, you could say; but just as the male and female gametes are very different, so male and female adults continue in the same vein. The male is subject to the underlying rules that it is the female that is the ‘limiting factor’ in reproduction, and the male that is the vehicle for purging the whole lineage of deleterious genetic material. These factors conspire to compel the male to compete fiercely with others of his own sex.

Our fertilised egg may be assigned male, and will then grow, in our human case, into a boy, who soon starts behaving not unlike one of those sperm that produced him. Research has revealed that by as early as just eighteen months of age, a boy is competing with his same-sex peers for a place in the all-male ‘pecking order’ or - as it’s properly called in biology - dominance hierarchy: henceforth DH. This is built up by individual boys non-consciously registering the outcomes of any contests with other boys they are party to and self-calibrating their rank amongst all the boys in their social group. (Not every permutation of pairs of males need fight, because the ‘gaps’ can be mentally filled in, by inference: a facility that has evolved for this very purpose: ‘transitive reasoning’.) No individual needs to comprehend the overall DH, which is merely an epiphenomenon of the whole process (Moxon, 2007). Without these ritualised fights and the resulting DH, males would try to establish who was ‘boss’ each time they met. So the DH saves a lot of pointless confrontation. It also helps females find males of equivalent ‘mate value’ to reproduce with, and this makes sexual reproduction far more efficient, and is a major reason why sexual rather that asexual reproduction has been retained generally throughout the animal kingdom (Ochoa & Jaffe, 2006). What is even more crucial about the DH though, is not that it does away with the need for constant contest, but what the contest is over and for.

The dominance hierarchy is usually and most fiercely male...

...and present in every species

The human male, just as the male in any other animal species, is challenged in various ways that test aspects of what you could generically call vigour. By pushing systems to an extreme, any genes he is carrying that are not working properly are revealed. Through taunts and fights that get ever more prone to serious escalation as he gets older, if he lives in a hunter-gatherer (or certain other types of ‘primitive’ society), he is very likely to be killed - a 50/50 chance or more in some societies. In the ‘first world’ of today, he is unlikely even to get seriously injured, but nevertheless more likely than not to attain only a lowly rank in the DH of his peer group. This will set him up for difficulty when he comes to vie for a place in subsequent peer-group DHs, which in turn will set him up for difficulty in reproducing. His rank is as all-important when it comes to women choosing him as a sexual partner, as to him is the youth and beauty of girls/women when it comes to his own sexual choices. Male rank is the basis of female sexual choice in all species where there is a DH, including the human (albeit, in the latter case, mediated through higher-level cognitive and emotional processes, along with cultural factors).

Women may appear to choose men simply according to how ‘good looking’ they are, but this is still choice according to status. The qualities that make men handsome are the very ones that particularly predispose to gaining male rank. Height is the single most important physical determinate of status, and correspondingly is the principal physical attribute a man has for attracting the opposite sex (the research on this is so clear that none has been done in recent decades, but recent work does show that height is the main source of discrimination for men in job interviews). As well as height, there is stature - build and muscularity - and facial attractiveness, which is a matter of the symmetry that indicates good health, together with certain features like the ‘chisel jaw’ that betray high testosterone levels. All of these are obviously key to a male gaining status, from toddler age onwards. Status is still what is being considered when it comes to aspects of personality, and I don’t mean just obviously competitive qualities like determination, though this in its various guises is very important. For example, a sense of humour shows self-confidence and social intelligence.

There is lots of research showing that status (male dominance rank) is the basis of mate choice by females generally (Klinkova et al., 2005; Cowlishaw & Dunbar, 1991; Di Fiore, 2003; De Ruiter & van Hooff, 1993); and that this is the case in humans in particular has been well reviewed (Buss, 2003; Okami & Shackelford, 2001). The finding would be even more pronounced if it were not for the drawing of some false distinctions. For example, Todd Shackelford and others found across many dozens of cultures that women choose men according to status, but also because of education and/or intelligence, and if they are dependable and/or stable (Shackelford et al., 2005). Yet intelligence is obviously an attribute key to gaining status, and it translates into educational attainment. Likewise, status translates into calm dependability and an established lifestyle. Having said that, dependability and reliability are best viewed as indicators of how long the male is likely to stay around to help to look after and provision children. So, yes, female mate choice is not just about status, but it is mainly so.

Another confusion is the notion that it is resources that women are after and not a man’s status per se. You can’t really separate the two, but clearly money is an excellent proxy for status, so that men will often pursue it seemingly as an end in itself. Yet when men discuss income, they talk of ‘K’ in terms of bands according to which they themselves are valued, rather than what such a level of income could buy. We know that even the highest of women ‘high-flyers’ still choose men with even higher incomes than their own, when clearly they have no need at all for a male partner as a provider. Research shows that having an income above remarkably low amounts has a negligible impact on happiness. Resources indicate status much more than status indicates resources. As Dawkins might say, resources are part of the male’s ‘extended phenotype’. There is no evidence to suppose that we are different from animals in that a male’s rank in the male dominance hierarchy is central to female mate choice.

The reason that a male instinctively starts vying with his same-sex peers from when he is a toddler is for the very purpose of calibrating to what extent he will be able to reproduce. That women may be interested in him if he is the winner in a male-male contest is no mere by-product: it’s the very thing he is competing for. DH rank is purposeless until it translates into mating opportunity and success.

Attaining only a lowly rank, even in societies where this does not seriously affect survival, will certainly mean difficulty in passing on to the next generation what have been judged to be a set of genes that have a degree of build-up of deleterious material that the population is best off without. Here the male comes up against the environment and may be selected against; though the environment in this case is the rather special one of other individuals: those of the opposite sex, that is. Here, instead of natural selection, he is subject to sexual selection. It’s all the same though. They are both forms of evolutionary selection, and they both drive the working of the male ‘filter’.

Self-suppression of reproduction

A lowly rank in the DH will most likely hinder a male in a more direct way. It’s becoming increasingly apparent that part and parcel of the biological phenomenon of relative dominance, is the way that it triggers a hormonal damping down of fertility and sex drive (Moxon, 2007). Physiological ‘reproductive suppression’ has been revealed in all sorts of species, and to what extent it is evident in an individual is apparently linked with and determined by that individual’s dominance rank. (The correspondence may be only a rough one, because there are costs to any adaptation that cancel benefits beyond the point at which ‘expensive’ fine-tuning is required.) Individuals seem simply to automatically suppress themselves, either entirely autonomously or in response to a signal from the top-ranked individual - by a non-conscious mechanism, of course. If you are high ranking, then you are not reproductively suppressed, or only to a small degree. But if - as is more likely - you are lower ranked, then you are reproductively suppressed to a greater degree; possibly completely so. In many species, the suppression is total for all but a sole breeder, the alpha male, with all other individuals acting as alloparents. These are the ‘co-operative breeding species’ (Creel, 2001). In most species, it appears that it must be a gradient of some kind.

Why would a male literally suppress his own fertility and sexual behaviour? For the same reason that he acquiesces to whatever is his rank in the DH; to which in any case reproductive suppression appears to be inextricably linked. It’s for self-interest and - as if that doesn’t seem strange enough - in the collective interest of everyone: all males and all females.

No matter what rank a male occupies, he has a strategic interest in being in the DH. There is usually no survivable alternative of being outside the DH, which includes all male individuals of a reproducing group, bar any that have been specifically excluded for trying to subvert it. Within it there is ‘policing’ through the evolution of psychological ‘cheater detection’ mechanisms to stop any individual from trying tactical subversion - anything that is directly or indirectly an attempt to gain sexual access other than through entitlement by rank (I‘ll have much more to say about ‘cheater detection’ in later chapters). At worst, a lowly rank offers a refuge. It may enable an individual to bide his time until he is better equipped to ascend the ranks. Any position is a platform offering the potential to climb the hierarchy, which a male will eagerly grasp because being the producer of the smaller gamete - and the victim of the polarisation between male and female this has driven - he has the potential to be a prodigious reproducer (though risks being consigned to reproductive oblivion).

For all the evident self-interest, however, the self-suppression of fertility and sexual behaviour is primarily driven by the biological imperative of gene replication itself, that in effect makes the male behave in the interests of the reproducing group as a whole. A ‘population genetics’ perspective is to study genes as they behave in the ecological reality of a whole finite reproducing population, rather than in what are merely their ‘vehicles’ (as Richard Dawkins called them) of individuals. It’s in this local total gene population that maximisation of replication is achieved, and this is not simply by making many more ‘vehicles’, but also by making higher quality ‘vehicles’ that are not themselves going to fail to reproduce and take out all of the genes they are carrying with them.[1]

As the female is the ‘limiting factor’ in reproduction, it’s important that all females reproduce, almost irrespective of their own quality. For males, on the other hand, it’s very different. Given that potentially just a few of the males can provide all of the required male gametes for the whole reproducing group, then it makes sense that only the very fittest of them are allowed to do this, because they make the offspring that are most likely to reproduce themselves and thus maximise gene replication. Within the reproducing group, setting physiological reproductive suppression so that it eases off the higher the male’s DH ranking achieves this beautifully. Though paradoxical it may seem, the ‘selfish gene’ here drives in most males quintessentially unselfish behaviour.

It may well be that this variable physiological reproductive suppression is what dominance first evolved for. It may be that the way females use the male DH to select which males to mate with was something that evolved subsequently. We don’t know. It would make sense, because it’s a fairly simple process for the brain, after it has registered its owner’s own rank, to simply trigger a roughly-corresponding level of release of a hormone that would in turn adjust fertility and/or sex drive to an appropriate level. It requires less sophisticated brain circuitry than that involved in working out the goings on in the alien society of the opposite sex; and we know we have to do this, so as to make choices about which individuals are worth having sex with.

The upshot of the male ‘filter’

Individual males are selectively disadvantaged so that they can fulfil their collective function of acting as what we might call the ‘genetic filter’ on behalf of everyone (Atmar, 1991). There is no objective criteria to this. The evolutionary process runs away with itself, being blind and quite capable of producing all kinds of absurd adaptations, such as the peacock’s crazily unwieldy tail - a case in point.

Male life is set up to produce disadvantage that is relative but nonetheless all too real; and this not for the minority but for the majority. So it is with men as it is with males of any species. The actual differences between males can be large or insignificant, or starting from a low or a high base; it makes no odds. Even if all or most men had as their common platform attributes sufficient to make them all a combination of the best qualities of, say, David Beckham and Albert Einstein. Given an elite that is still better endowed, however marginally, then the glut of Beckham-cum-Einsteins will be consigned to relative or even total reproductive oblivion. The reality is that by any objective measure, almost all men alive today are Beckham-cum-Einsteins. This perennial relativity, together with the drive to reproduce being fundamental to what we all are, means that males are trapped. To avoid social denigration, they are obliged to fulfil the biological role of acting as ‘genetic filter’ on behalf of the whole local reproducing community and, in effect, ultimately for the species as a whole.

This stark truth, and the contrast with the female, is behind the whole tree of motivation and behaviour common to each and across all species, and how this is dichotomized according to sex. Human social psychology must be attuned to and support this state of affairs. Evolutionary science would predict that, lurking beneath the veneer of our supposedly equitable and egalitarian modern societies, there must be profound prejudice against the male sex: by men and women alike. In fact it’s startlingly obvious on the surface once you know where to look, as I will be demonstrating. It’s apparent in every scenario where men and women come up against each other, so to speak. The way that prejudice against men is evident throws light on our social psychology, that has built on the essential difference between the sexes, and to make matters ever worse for the male sex.

This won’t essentially change, but even though we can’t ameliorate it in any essential way, we can do so in some respects. We can make ourselves aware that we are playing a game that artificially stretches out the men we know in our communities so that most falsely appear in some respects as losers, nitwits, weaklings, or devils beyond the pale. In our supposedly equitable societies we champion the ‘socially excluded’, but we have been unfairly excluding huge numbers of people - the vast majority of ordinary males - all along. Then, to outrageously compound the offence, we expressly exclude them from the consideration normally afforded to those socially excluded and in need of support.

Instead of ameliorating this most profound source of unfairness in all societies, we have been doing very much the opposite. Not understanding that our psychology is literally to ‘do down’ males, we have rationalised this into thinking that there must be something wrong with them all - we assume that our generic ‘doing down’ must be for good reason. This ‘folk prejudice’ has been ridden piggy-back by the politics of feminism that claims to identify just what it is that males supposedly are doing wrong: that they ‘do down’ females!

Males of all species do anything but. They prize females, for the essential biological reason that females represent the logjam in reproduction. Will the proponents of PC and extreme feminism continue to congratulate themselves when they find out that the notion that men somehow ‘oppress’ women is the biggest howler in history?

Once we get this inversion of reality right-side-up, then at least we can stop that part of our biological predisposition from turning into a political perversion. This is not to claim victim status for men. Not only are some men startlingly successful, but most if not almost all men are anything but deficient by any objective criteria. What is important to further social justice is not to give victim status to men but to revoke it for women. The entire ‘victimocracy’ that PC has created needs to be shown the door if we are to have any proper perspective on the reality of disadvantage, and thereby arrive at social justice. The linchpin of the ‘victimocracy’ though, is its major sub-group, and majority of the population: all of the non-men.

Summary

We knew, roughly, why there is such a thing as sex, but we didn’t know why there are the sexes. The reason we’re not all bi-sexed is not because of a problem that sex itself evolved to solve. Sex, strangely, made the problem worse.

To get shot of genes made faulty in copying, they are in effect ‘quarantined’ away from the female half of the reproducing group, because this is where there is already a logjam. So the males act as ‘genetic filter’ for the whole lineage.

Most ‘quarantining’ is not actually placing faulty genes in males and away from females, but making them more apparent in males, on whom selection can then operate. Males are driven to behave in ways that expose any genetic defects they have, and females then choose the better of them. In this way females augment natural selection to help the male ‘filter’ to work.

The male ‘filter’ function is still further entrenched by a male‘s rank in the dominance hierarchy directly impacting on his fertility. A male literally suppresses his own reproduction to a degree in line with how useful he is to the local reproductive pool.

Inevitably the female is valued and the male devalued. This evolved prejudice is now bolstered by a politically-motivated misreading that has got it all entirely back to front. Widespread understanding of this will be for the good of us all.

1 This generally-accepted contemporary position transcends the stale old debate about whether there is ‘group selection’, that Richard Dawkins’ over-emphasis on the individual gene level of analysis spawned (Keller, 1999). Lineage selection serves to favour long-term over short-term benefits, in any case (Nunney, 1999). It is now agreed that to understand natural/sexual selection you have to look simultaneously at the individual gene and the whole gene pool.