9: Sex at Work -- Why women are not in love with work, yet the pay gap is so small

The opportunity for men to compete with each other for status is universally provided by work, for which men receive as reward the proxy for status: money. Status acquisition is the only option for men if they are to have any ‘mate value’ and obtain sexual partners; either long-term or fleeting. From a biological perspective, women neither need nor have any use at all for status (that is rank as measured in male terms), because they already have ‘mate value’ inherent in the degree to which they have a combination of youth and beauty. Some people are just more honest about this than others: witness this recent posting on the classifieds website Craiglist:

I’m tired of beating around the bush. I’m a beautiful (spectacularly beautiful) 25-year-old. I’m articulate and classy. I’m not from New York. I’m looking to get married to a guy who makes at least half a million a year. I know how that sounds, but keep in mind that a million a year is middle-class in New York, so I don’t think I’m overreaching at all.

This led to an equally candid response from a (male) merchant banker:

In economic terms, you are a depreciating asset and I am an earning asset. Your looks will fade and my money will likely continue into perpetuity. You’re 25 now and will likely stay pretty hot for the next 5 years, but less so each year. Then the fade begins in earnest. By 35, stick a fork in you!

Men never choose women on the basis of status; such male criteria being, biologically speaking, a meaningless way to view women. Work is consequently very much on the male side of life’s equation, and it must be expected that men will tend to want much more of it than do women - both for the monetary reward and to ‘climb the greasy pole’, for which they will be prepared to put in more effort regarding the task, and to enter into more competition. Inevitably then, for this reason (even before we consider various others) men will always, on average, outdo women - in top jobs especially - but also across the board, in terms of pay and promotion. This is reflected in what is found when looking in the most general terms at the difference between men and women (see chapter five). In measuring almost any ability or performance, men on average outdo women, and even a small average betterment translates into overwhelming male preponderance at the top end because of the different nature of distribution according to sex. Male performance generally is spread wider, with both over- and under-performance compared to that of women, which tends to bunch in the mid-range (see chapter five).

Women in going backwards can’t be ‘catching up’

Even with perfect equality of opportunity, it should be expected that for a top job like director of a leading company, men will easily be beating women into the boardroom. And so they are. Not only is the proportion of women directors of the top hundred UK companies just one in ten, but almost all of them are non-executive. Even across the top 250 UK companies, at the time of writing (2007), there were less than a couple of dozen women who have any executive responsibility. Yet government ministers, quangocrats and activists continue to claim that it’s merely a question of time before women catch up with men at the top. This social inertia notion might have more credence if the number of women in positions that are a springboard to the directorial board was increasing. They’re not. They’re declining.

Of the senior management posts in the 350 largest UK companies, only 22% were held by women in 2007, compared to 40% in 2002. That’s an enormous drop in just five years. The exodus is still greater if you look at the less high-powered ‘head of function’ roles (that is, positions where there is anyone reporting to you) in the 250 largest UK companies, where women declined from one in five in 2002 to just over one in ten in 2007. Senior and ‘head of function’ managers are the pools of women from which future board members could be drawn, so we can expect corresponding falls in the numbers of women on the board, even though it’s from a very low base. This is already happening. Of the top 100 UK companies, there were just twelve executive directors in 2006, which is almost a halving of the number from the previous year. It’s been happening for some time: the same story of decline in women on the board and executive directors had been apparent at the onset of the new millennium.

The news had appeared to be advancement, when in the decade up to the millennium the proportion of all companies boasting a woman on their board had climbed from just two percent to ten percent. This is illusory, however. Many of these are minuscule businesses, directed by the owners themselves. Most business growth has been of such concerns, and a significant proportion of this has been by women. There are now a million self-employed women in Britain. In business, women tend to be present as decision-makers in inverse proportion to the degree of hierarchy. In big companies, not to have a token woman board member is bad PR, and there is no commercial risk if an appointee is non-executive; and this accounts for most of the relatively small numbers of women there are at this level. Likewise in management, the rise of women is not in private-sector line management but in public-sector staff roles, as would be expected with the recent growth in the public sector. There is no likelihood of reversing the decline of women in the commercial hierarchy, looking at the figures for those enrolling on business courses. The London Business School’s female intake is only one in five of the total, and this is mirrored in business schools nationwide. There is subsequent heavy attrition in numbers of females, not just owing to their family commitments, but also, compared to men, through their having less focus and more other interests that conflict with both the desire and the effort necessary to climb the hierarchy. And this does not take into account the high proportion of men who will get there through other, less direct or riskier routes, who never went to business school. Business is the field of the entrepreneur, after all, who is born with the attitude and the drive. He’s not a product of a college course. Just ask Sir Richard Branson or Sir Alan Sugar.

* * *

All this is astonishing in the face of the constant media exhortations and government pressure to get more women into senior positions. It takes time to climb the corporate ladder, but the aspirations of women at least to get into the lower echelons of senior management should have been fully realised many years ago now. Social inertia explanations have been replaced with a resurrection of the old rhetoric about discrimination; though now supposed to be in ever subtler form. There is refusal to face up to the simple fact that women do not cut this particularly competitive kind of mustard in the way that men do.

Instead of going into business, women have concentrated further in areas where they have always been established: the public sector in general, but particularly in education and health. Anywhere where real competition, risk and innovation are less important. Even then, near the top of an organisation in a ‘female’ employment niche/sector, the sheer hassle puts women off. (Actually ‘female’ sex-typical work has shrunk no less than the male equivalent: the growth is in sex-neutral work.) Managing a company at the top is all about dealing with irreconcilables in a moneyed world. Conflict, in other words. This is not what women are looking for at work, as I will explain.

Women are not orientated towards work

How women behave with respect to seeking top jobs is a reflection of women’s attitude generally to the world of work. In whatever field, that the pattern of work amongst women has changed hardly, if at all, was first highlighted in 1996 in the first of a series of books by the world’s leading expert on women in work, LSE sociologist Catherine Hakim. Over a thirty-year period, British women certainly did take up work, but all of the extra working was part-time, with no increase whatsoever in full-time permanent work:

All the increase in employment in Britain since 1950, from 22 million jobs in 1951 to 26 million jobs in 1997, consisted of growth in female part-time jobs. By the early 1980s, two million full-time jobs were lost in the male workforce, most of them in manufacturing. Another one million jobs were lost in the female workforce, but then regained in the early 1990s. The only increase in female employment since the 1950s, and indeed since 1851 or before, is the massive expansion of part-time jobs, from 0.8 million in 1951 to 5.5 million by 1997....The headcount increase in female employment conceals an almost unchanging contribution of total hours worked by women, which remained below 33% up to 1980 (Hakim, 2004).

Remarkably, the proportion of women in full-time permanent work in Britain is the same now not just compared to what it was a few decades ago, but compared to what it was 150 years ago. I checked with Hakim that the conclusion remained, and she replied (citing Hakim, 2003):

That conclusion is not altered: there is no substantial difference in full-time permanent female employment. In fact, researchers in several other European countries report the same finding, if they compare figures over a long period. And additionally, current evidence for Britain suggests that women’s continuity of employment is declining rather than rising, so full-time and continuous employment actually covers only about 10-15% of women in Britain - and many other European countries where appropriate data exists.

The importance of this finding is difficult to overstate. It means that all the expectations of social and economic change, of greater equality between men and women in the workforce, and in the home, have rested, in practice, on the creation of a large part-time workforce. This is clearly nonsense. Even if part-time workers were identical to women working full-time in terms of qualifications, occupations and work experience, differing only in their shorter working hours, they would be poorly placed to provide the vanguard of change in the labour force, and the catalyst for wider social and political change.

Recent Labour Force Survey figures (2003) show that there are not far off twice as many male full-time workers as there are female, but there were only a quarter to a third as many male part-timers as there were women. So the labour market is enormously skewed according to sex in preference for full-time over part-time work or vice-versa, for all the media talk about work now being a woman’s world after structural changes favouring the service economy. Surely there must have been a substantial change in the most recent years to coincide with women having children later and later in life, and the much lower starting base for women compared to men? Well, between 1995 and 2003 the number of women in full-time work went up by about 200,000, but the increase in part-timers was almost exactly one million - five times as many. The result was that the percentage of the female workforce in part-time as opposed to full-time employment was not just maintained but actually rose from 44% to 48%.

What’s going on? It appears from the latest research that just as with women in top jobs or jobs not obviously appealing to women, there are signs of a counter-trend leading to a decline in numbers of women in any kind of full-time employment; women preferring instead to work part-time. The Institute for Social and Economic Research published the most extensive study on this issue anyone had so far attempted which showed that:

Over 40% of women employed full-time prefer to work fewer hours at the prevailing wage, while only 4% prefer to work more hours. However, almost three-quarters of women who work part-time are unconstrained in their work hours, 10% prefer to work fewer hours and 19% prefer to work more hours....In 1991, 28% of women in employment wanted to work fewer hours at the prevailing wage, while 10% wanted to work more hours. By 1998, 34% wanted to work fewer hours, while only 7% wanted to work more hours (Böheim & Taylor, 2001).

Men showed the reverse and even more strikingly in all categories. The authors discuss at length possible constraints on choice of working hours, and show that while there are some, they are not serious obstacles. The choices made by the women about what they would prefer as ideal are real preferences, so over time they are likely to translate into actual working patterns. Notice that the ten percent increase over the decade of women dissatisfied with full-time working roughly corresponds to the increase of women in full-time work from 1995. It appears that most of the extra new recruits to full-time work either never really wanted to be there, or having tasted it realised that the grass, instead of being greener was, parched. Perhaps too, disillusion had started to set in amongst more longstanding women workers who had tired of the novelty of juggling home and work.

It might well be that the dissatisfaction is far more even than the ISER research shows, and that this could be shown if women are allowed to be more candid. In June 2001, Bupa/Top Santé published a survey of 5,000 full-time working women in the UK and found that only nine percent said they would still work full-time if they had a realistic choice. This compares with a majority of men, because men have no concept of an alternative to lifelong full-time work which does not mean criminality or poverty, and - more to the point - loss of esteem. The minority of men who would give up work would do so only for a guaranteed independent income. Women, on the other hand, have every prospect of being ‘kept’ by simply staying at home and relying on their husbands to continue working full-time. Until very recently, this was actually the norm even in the poorest of working-class districts.

It seems then that more women are set to move away from full-time and into part-time work, and this already seems to be happening. The shakeout of stay-at-home women from the era in which they were not expected to go out to work had run its course some time ago, so the effect of a shift to part-time work will therefore mean a reduction in women full-timers. This is likely to be boosted further, and quite considerably so, by the reaction already apparent against what is being seen as a burdensome expectation the other way: nowadays women are generally cajoled into work, and this is becoming a focus of resistance. Well publicised middle-class female ‘role model’ figures have become vocal on this question. Job sharing is moving up-market, and many of those women who do achieve better jobs and pay but do not go this far, are likely to readjust their work-life balance to reduce working hours. This will have the effect, of course, of slowing or halting their rise into the topmost positions.

* * *

Women have woken up to not just the stress and thorough lack of empowerment that work actually provides, but what is for women the pointlessness of it. Their message will be more and more warmly received, though working-class women have always known the harsh reality of work. The push towards women treating work in a similar way to how men do, though clearly still persisting amongst a small minority of women, will seem in retrospect a short-lived bubble, with women who do remain in full-time work doing so only through a perceived necessity. This not least because house prices have risen owing to the rise of the dual-earning couple, so women are to an important extent now locked into work. (Another consequence of the dual-earning expectation is the depressive effect on real wages: 2006 being the only year in the last two decades when there was a zero increase in disposable income. In the US, inflation-adjusted hourly and weekly wages in 2006 were below where they were at the start of the recovery in November 2001.) Hakim cites further research showing that secondary earners forced to work full-time are the most dissatisfied of all workers. So again, the social inertia theory to try and explain disparity between the sexes is a hopeless fit to figures which show precisely the opposite of what it predicted. This is all the more remarkable because it comes in spite of the relative collapse of the female archetype of homemaker and mother, which has had a profound impact on women, and as a psychological ‘projection’, is the source of the bizarre notion that the male is redundant. The redundant sex is actually the female.

Underlying all this is what Catherine Hakim has identified as a persistent set of alternative lifestyle preferences that women make. Only a minority of women (between ten and fifteen percent) are ‘work-centred’ and so work continuously in permanent full-time jobs, whilst a rather larger proportion (a fifth) are ‘home-centred’, giving priority to children and home-making, and don’t want to work at all. That leaves the bulk of women making up the balance in the ‘adaptive’ group, who fit employment around family responsibilities, either working part-time or moving in and out of full-time jobs. The women of the ‘work-centred’ sub-group are the least representative of their sex, because the attitudes of women in the ‘adaptive’ group are very similar to those of the ‘home-centred’. They see work as not primarily about bread-winning or having a career, or of developing an ability or skill; but more as a social activity providing supplementary income. They also have the same attitude as ‘home-makers’ regarding the sexual division of couples into a wage-earning male and a home-making female. Only about a quarter of women who hold full-time jobs view their working life as a career.

Hakim herself sees the distinctions between women’s preferences as a normal distribution curve, with the more extreme minority choices at either end and the bulk of women in the middle. But at the same time, she sees the three categories as enduring and qualitatively different. However, she ignores an underlying homogeneity, as revealed by the remarkably similar attitudes of women across the first and second most populous categories. This similarity is because women do not compete with each other in the way that men do - for status. The difference that makes the ‘work-centred’ women stand out is that they have elected to progress up a career ladder. For some this will be through intra-sexual competition (with other women), or because the job had become an end in itself; but these motivations are usually far weaker than they are in men. Ultimately women’s ‘climbing the greasy pole’ is not for the reasons that men have to, but - as evolutionary psychology would suggest - so that they place themselves in the milieu of higher-status men. They may have careers but their working is anything other than an end in itself, just as it is for most other women who work. Some women carry on, forever trying to climb; forgetting to jump off as their working life becomes an unintended end in itself. These women appear to be very like men, but they are not.

In trying to apply her ‘Preference Theory’ to men, Hakim finds that the overwhelming majority are careerist, with a very few ‘home-makers’, and the remainder she sees as ‘adaptive’, similar to the predominant group in women. But this would be to assume that, like women, men are compromising between working and home-making. It’s clear to me that men are not doing this. They are dividing time between work and alternative means of acquiring and maintaining status - sports, hobbies, pressure-group politics, some blind-alley obsession, developing something that may turn into work, serving in an official body of some sort; a vast array of activities that are competitive in some way. If a man’s work is low-status, dead-end or in some way unsatisfying, then he can spread his options of how to make his way in life. One option he is not interested in is to become a home-maker. A ‘home-protector’, yes; and to some extent the builder of the nest the woman then tends. If he has no option, of course, a man will become a home-maker as a single parent; or as the one who stays home simply because he earns much less that his wife, who otherwise would have to. These are forced choices though, and in this scenario divorce rates multiply several fold as women seem to see their husbands as having lost the status which was the basis on which they married them, and men register within themselves such a diminution; so both parties become dissatisfied with their situation. Hakim’s three alternative preferences of work that she sees as applying to both sexes is her interpretation, but a better one is that they are unique to women. They don’t apply to men. Hakim assumes some form of social construction model which does not admit of a natural sex difference, and so she doesn’t look for underlying evolutionary explanations. She sees her findings as necessarily having to fit a unisexual model.

* * *

Long-term data show that women’s preferences (rather than circumstantial constraints) are increasingly important in their decisions about work, especially for younger women (Blossfeld, 1987). Furthermore, this is so regardless of their level of education, social class, and whether or not they have children. Contrary to what most would imagine, research demonstrates that women are not constrained from working by childcare and home-making. This further underlines the homogeneity of the three preference groups, and points up that there is a fundamental divide between men and women in a systematic and uniform difference in attitude to work or, more precisely, to status-seeking. The upshot is that no steady increase of women in work can be expected. The opposite is likely, as in France where the ‘home-centred’ group has swollen to a third of all women.

For a look in detail at the preferences of women in a professional group in Britain, Hakim chose pharmacists. The women had the same qualifications as their male colleagues, but markedly different work patterns. Male pharmacists see their work as a platform to launch into self-employment or management, whereas women see it as a haven for flexible, mother-friendly, part-time employment with no responsibilities to interfere with those of the family. And there seems to be another, time-honoured, aspect to this female ‘pseudo-career’ path revealed by Hakim’s findings. Going into jobs requiring high levels of education is as much making use of qualifications to ‘trade up’ in the marriage market as it is in the market for jobs. The statistics in many countries show that the husband is now much more likely to be the better-educated spouse. It’s not just that women are using education to ensure meeting Mr Right, but that Mr Right is, as ever he was, a man not so much able to offer more resources than a woman can muster - after all, she is now often anything but poor herself - but a man high in status.

* * *

The commercial office world, far from becoming ‘feminised’ has actually got more cut-throat than ever before. Yes, there are fewer heavy shopfloor industrial jobs to soak up unskilled male labour, so the workplace overall has in this sense become less of a man’s world than it was. Equally, though, ‘feminine’ jobs have disappeared or have become ‘gender neutral’, and this is an ongoing trend. Nobody anywhere is saying that work has got softer: everyone agrees it’s more than ever dog-eat-dog. Women can compete alongside men, but this suits only a minority of women, and not a large one at that; and even then, they won’t be motivated at root in the way that typically men are. (This is not to say that some women are not indeed highly motivated. Some women have male ‘brain patterning’ and so may be ‘focused’ in a male manner; and/or they may be particularly strongly driven to seek high status males.).

There is no reason why those women who feel cut out for it should not opt for a work life as a ‘pseudo-male’, as it were; as increasingly they have been encouraged to do. It‘s just that the majority of those women who want to work full-time have ample scope to choose a different, less overtly competitive sector or niche. Something that has a more social front end; more to do with care; perhaps more creative, rather than, say, ruthlessly deciding between irreconcilable options in the boardroom. This is one reason why employment sectors and niches have always tended to polarise the sexes, and why we should expect not less but more of this. That most women still continue to shun the male work model confounds social-trends predictions and undermines the tediously regular claims of discrimination by the late and unlamented Equal Opportunities Commission. Conversely, the convoluted and flimsy excuses used to explain women’s lack of progress is evidence itself of a root deeper than social norms - evidence which gets stronger with every year that passes. And all this is despite the collapse in female roles - housewife, mother, even exclusive sex-provider - which has left women feeling they have less scope, and so further encouraging them to fill male roles.

The sexual division of labour

The distinction between male breadwinner and female home-maker roles that underlies the different attitude of the sexes to work, is so great that it’s often claimed that housework is somehow imposed on women as part of men’s supposed ‘oppression’ of them. Men’s burden as ‘wage slaves’ is said to be more than offset by women doing all the housework, which curtails the scope women have to participate in the jobs market, making their choices, such as part-time rather than full-time working, forced.

This is all myth. The cry of ‘women work more’ has by repetition assumed truth. Hakim is absolutely conclusive:

Adding together market work, domestic and childcare work, the evidence for the 1970s onwards is that wives and women generally do fewer total work hours than husbands and men generally, and that women’s dual burden of paid work and family work is diminishing.

The gap was five hours per week in the USA in 1991, though very recent studies - as Hakim has pointed out to me - show the total work hours of the sexes to be the same.

A misleading picture of overworked women has built up partly through a focus on mothers with young children, as if this period is typical of their whole life. It‘s typical of only a few years. Children need far less care as they get older, and then leave home. More misleading still is to include as work women’s natural nurturing behaviour towards their children, as if it’s an onerous task on a par with working for an employer. Economists would see it not as productive work but as consumption, because it loses its value to the mother if someone else was substituted to carry it out. Much housework would also not be work, given a reluctance to delegate even to the husband. And it can’t be claimed that women who stay at home or work part-time are doing unpaid work. They are paid directly for doing housework and childcare by their full-time working partners.

That women who combine work proper and housework are not having the hard time juggling demands on their time that it is made out, is provided by analyses of what women get up to when they are full-time homemakers. Inefficiency is hardly the word, according to Hakim. If you include activities that look like housework but are done for pleasure, then half the hours are wasted and far from being work really represent consumption:

Studies of full-time home-makers reveal a remarkable lack of concern with efficiency; on the contrary, tasks are constantly expanded into huge amounts of unnecessary make-work...endlessly repeating the same unskilled tasks. Full-time home-makers cleaned and shopped daily instead of weekly, washed and ironed sheets twice a week instead of once a month....Variations in hours spent on domestic work are not explained by the number of children being cared for, access to labour-saving equipment and other amenities, or the purchase of more services in the market. One explanation for the reluctance of husbands to help with domestic work is the suspicion that there might be no need for it (Silverman & Eals, 1994).

Men by contrast are reluctant to divert effort into looking for dirt they fail to see - research confirms that men are poorer than women at spotting objects in an array, and this explains why men literally tend not to see dirt. Why should a man do housework to a partner’s higher standards than his own, when this is his partner’s domain, and is something she does well and (as studies reveal) is not so easily bored by - and may even enjoy?

* * *

The family is a beautiful example of a mutually-beneficial division of labour, with the sexes respectively doing not just what they do best, but what they like doing best. Just suppose that the extreme feminist line of a universal ‘superwoman’, always better than men, was not nonsense but true. Let us imagine that women are not just the best at rearing children but also model workers. Surely this would then mean that women should do both, with men filling in around them with complementary, albeit inferior, contributions on both fronts? Well no, this is not how things would pan out. The most fundamental insight of economics - the law of comparative advantage - tells us why. Instead of making all kinds of items you need, it’s far easier to make just those things that you can make easily and quickly, and trade with those who also can make what you make, but less easily and less quickly. This is what human beings have always done, long before any law and customs to do with trade were devised. Trade with a division of labour between a man and a woman makes sense regardless of their relative merits in whatever sphere.

Even if women were better at everything than men, nobody seriously doubts that men are better in the work sphere than they are homemakers. Few people doubt that women make better carers of young children than do men. Men would (nearly) always be the primary breadwinners simply because they are less bad at this than they are at bringing up baby. Women would (nearly) always be the primary carers because they are clearly evolved for this function whereas men clearly are not. These differences reinforce each other in a positive feedback loop and lead to polarisation. Given that all men and women are either in a sexual relationship or looking for one, and equipped psychologically to anticipate the consequences, then the family scenario is the default social expectation guiding economic behaviour. Factor in the related intra-sexual competitive drive of men, which has only a weak parallel in women, and it’s obvious to anybody that the feminist ideal of a world of work devoid of any parameters related to sex, is perpetually unrealisable.

Why there is a pay gap, and why it’s so small

With the failure to understand the sex differences in attitude to work, the pay gap supposedly results from sex discrimination. And just as with the failure of women to get anywhere near parity with men in getting into top jobs, the stubbornness of the pay gap to close is put down to social inertia or ever more subtle forms of sex discrimination. I’m not dealing here with the historical pay gap that certainly did exist (which I dealt with in chapter seven), but which was actually not in any way against women’s interests in the context of a view of social justice that focused on the family household. Here I will confine myself to the contemporary pay gap - with women on average earning four-fifths of what men earn.

That the pay gap has nothing at all to do with discrimination was confirmed in the 2006 report by the Women and Work Commission, which instead blamed the culture in schools and the workplace (but which was an indirect way of saying that actually it’s down to women’s choices). It remains anathema to say this, because it reveals that women have not and will not change - that is, they will not change the basis of their preferences, though they will react contingently. Not only is the pay gap not due to discrimination, but that it’s as low as it is indicates sex discrimination against men. (I will come on to the proof of this discrimination at the end of this chapter.)

The pay gap is easily explained by men tending to have harder jobs, putting in longer hours, taking more responsibility, etc; which in turn is easily explained by multiplying together the impact of the sex difference in how performance generally is distributed, and the radically polarised attitude to work of the sexes. Then there is the drawback women have in moving up any employment scale in having and raising children. Breaks in employment or reducing full-time work to part-time, inevitably hold women back, and there is nothing corresponding in men’s life that systematically produces anything similar.

There are still other reasons behind the disparity in average income between the sexes, to do with the predilection of women for work that is more in keeping with their natural tendency towards social networking, as opposed to the natural male inclination towards goal-directed competition. Jobs that are at the social front end, such as receptionists; and caring roles, such as nurses; are overwhelmingly female staffed. Most of the sex-typical female kinds of employment - even when full-time - tend to be low paying, for simple supply/demand reasons: they are pleasant and socially rewarding positions that are easy for employers to fill. It’s certainly true that female sex-typical work sectors are very much reduced as a proportion of the economy than they once were - going ‘into service’ was by far the most usual female job prior to the First World War - but female sex-typical work niches within the full range of work sectors are abundant, and ‘gender neutral’ jobs in administration that are at least conducive to women have grown substantially. With thoroughgoing equal-opportunity initiatives, most of the population is considered eligible for recruitment, so pay levels can be pitiful, which puts men off. Women have made up most of these new recruits, so again average female pay across the whole economy will be further reduced.

* * *

The ‘pay gap’ is a misnomer when you consider that it’s less important than the ‘family gap’: the difference in earnings between partnered mothers and single childless women (Harkness & Waldfogel, 1999; Bayard et al., 2003). A woman without children who is also not partnered, on average has roughly the same earnings - actually slightly more - as the average man (Hecker, 1998). Even more telling are the pay differentials between hetero- and homo-sexual couples (Berg & Lien, 2002; Carpenter, 2005). Lesbians enjoy an earnings premium of 20% compared to heterosexual women. The difference between lesbians and all other women may best capture the impact of being female: compared not to men but to a null baseline. Whereas being a woman with a family normally is a brake on earning, for men with a family it may be a spur. Married men earn on average 25% more than do single men (and also, interestingly, compared to gay men).

Is this because women choose better earners as marriage partners? Or is it that men, once they have a family (children and/or a spouse) are then motivated to earn more money? (Cohen & Yitchak, 1991.) Correspondingly, do women who don’t have primary responsibility for earning then take their foot off the pedal and/or displace their own expectation for earning on to men? It’s not that a wife frees a man from domesticity so that he can concentrate more on earning, because single men have little domesticity to offload, and may well take on more in a female-run household where standards are much higher. The other explanations are probably all part of the picture. The point is that all of the differences are between individuals of the same sex in different situations. The ‘pay gap’ resolves into a within-sex, not a between-sex difference. The ‘marriage gap’ amongst men reflects a difference in motivation between sub-groups of men, but it says nothing about the overall difference in motivation between men in general and women in general.

There are a host of reasons, many inter-related, that might incline us to the view that the actual figure of circa 20% seems far smaller than it should be. The standard PC viewpoint may well posit the problem in reverse: instead of women being discriminated against, either men are being discriminated against or women are being given preferential treatment. Or both. The lamentable understanding of what lies behind the pay gap is evident in the slew of books in the late 1990s demanding its end. Authors such as Suzanne Franks (a truly risible analysis titled Having None of It) marshalled the supposed evidence for sex discrimination in ever more ill-thought-out fervency.

* * *

The intransigence of the pay gap to fall progressively to zero is one thing, but in many developed world countries the pay gap is actually widening. And it’s widening in the very places where there is most effort to close it. In Sweden, the pay gap hit a floor of 18% in 1981, more than 20 years ago. By 2000 it had risen (on comparable, adjusted figures) to 21% (Spant & Gonas, 2002). Sweden is ahead of any other country in measures of trying to combat the pay gap, so Sweden should be furthest down the road to getting the gap down to zero. The pay gap has defied feminist theory in not falling to zero, but instead bottoming out nowhere near zero and then going into reverse.

The Swedish experience is caused by the very family-friendly policies designed to get women into work. Because women have a fundamentally different and often antipathetic attitude to work, then the higher the proportion of women who feel compelled or deceived into working, the ever greater proportion of these will be women who really don’t want to. Instead of embracing work, they go into poorly-trained, sex-segregated jobs that demand little or no commitment or compromise and which pay correspondingly poorly. This drags down the average female wage.

In countries where women are more or less universally compelled to work, so that even the core ‘home-makers’ are begrudgingly at work; then the pay gap can be very much larger - up to 50%. This was the case paradoxically in the very country where sex equality was most explicitly articulated - prior to 1989 in the Soviet-block state of East Germany.

Will there be a pronounced retrenchment of the pay gap everywhere? It’s hard to see why there won’t be. And there is another factor that is surely set to come into play, in addition to the attitudes of most women to work. Given the DH-inspired propensity of men to compete with each other for status, and with income being the most straightforward proxy for status, then albeit that their aim is success in competition with other men, men gauge their relative status in part at least by their income above a general baseline, and women’s wages are very much part of this. So although men are in no way competing against women, women’s wages insofar as they register and are generally assessed, represent in men’s minds the sort of money you would earn if you weren’t trying, as it were. Men correctly surmise that if they can manage to earn only what lowly-paid women typically earn, then few women will be interested in them as potential sexual partners. A 1996 ICM research poll showed that the majority of men will not take on what they regard as women’s work. Research has also shown that men have cognisance of a reference income with respect to total benefit levels: men (but not women) think in terms of the ‘reservation wage’, which is that wage level which is sufficiently above benefit levels to make work even begin to seem worthwhile. The general baseline of earned income has risen in the wake of measures equalising pay between the sexes, and also more particularly through in-work benefits/tax credits that are skewed to help women. Inevitably therefore, men on average will take action to boost their incomes so that they are restored to something like previous differentials. Apart from ways of doing this that exploit loopholes that can be closed, an increased sex difference in pay cannot be clawed back by measures of sex equality, for the simple reason that such measures have already been introduced and their impact is a one-off ‘gain’. There is nowhere else for feminists to go except to overtly discriminate against men.

The value we put on jobs, and their sex segregation

The argument that the pay gap is discrimination is tied up with a widely-accepted notion that women’s jobs are less valued than men’s jobs, simply because women do them. This is not just a reversal of cause and effect, but assumes that the prestige of any job is arbitrary. Job prestige is not arbitrary but bound up with remuneration, which is a strong reflection of profitability, supply and demand, etc. Status is attached to a job because the qualities required to gain the position are in short supply. Status in the world of work, where employers have to stump up hard cash, is never arbitrary.

In the mid-nineteenth century office work was a high-status male preserve. At the cutting edge of the labour market, it required a level of education obtainable only by a very few. A combination of book-keeping skills, writing and record keeping, and a sound knowledge of most aspects of the business were prerequisites. The scarcity of these skills attracted a premium in pay that was the necessary ‘family wage’ for a man. As education levelled upwards, and as women were now themselves being educated above primary level, then it became far easier to fill posts. Consequently, salaries fell. Advances in technology allowed for de-skilling and the separation of tasks from each other and from managerial functions resulting in the office coming to resemble the factory. This was just the sort of work educated and upper-working-class or middle-class women were seeking. Factory work was often unsuitable for women, because it sacrificed femininity and (usually) hygiene. The affordability of this workforce ensured mass availability of jobs in large organisations. As ever in search of (and being pushed into) a breadwinner’s pay, men were obliged to move on to more challenging pastures either outside of this area of work altogether or by moving up into management. So it was that women predominated in clerical work by default, and it became routine and female.

At the other end of the spectrum of jobs that men but not women do (or used to do), jobs are anything but more valued. These jobs are less valued and may be paid well only by virtue of how dirty, heavy and dangerous they are. The supply of labour to do such work is restricted by the willingness of people to do it, and by fitness requirements; but also through unionisation to turn a weak bargaining position into a strong one. Male coalitional behaviour is particularly useful here. A major constraint on labour supply that helps to keep wages buoyant in these jobs is that natural care and protection of women has nearly always precluded them from this type of employment. At most times in history, and still today, we oblige men to do all the work that might in any way compromise a woman’s ability to safely bear children, her beauty or her dignity. To expect women to do such work would reflect badly on the men around them: they would be seen not least by other women as having fallen down on their universal ‘care and protection’ role, and this would translate into loss of status. A notable exception here is the ‘cleaning lady’, but it’s exceptional because it’s just an extension of domestic cleaning duties that are part of a woman’s sense of being a home-maker. When any cleaning work moves far beyond any parallel with the housewife role, then it becomes all-male.

There have been times in the past when economic necessity has meant that all household members including children, let alone women, had to join men in dirty and dangerous workplaces; notably the coal mine. However, women did the less onerous, lighter jobs away from the face, that were consequently lower paid; but which in any case came to an end after the public uproar when they came to wider attention. Reports in the early-nineteenth century of coal-blackened and bare-breasted women working underground prompted a royal commission and then an act to ban it. (The jobs were sex-categorised, but it wasn‘t possible for the sexes to physically segregate in a coal mine, and this is what caused the uproar.)

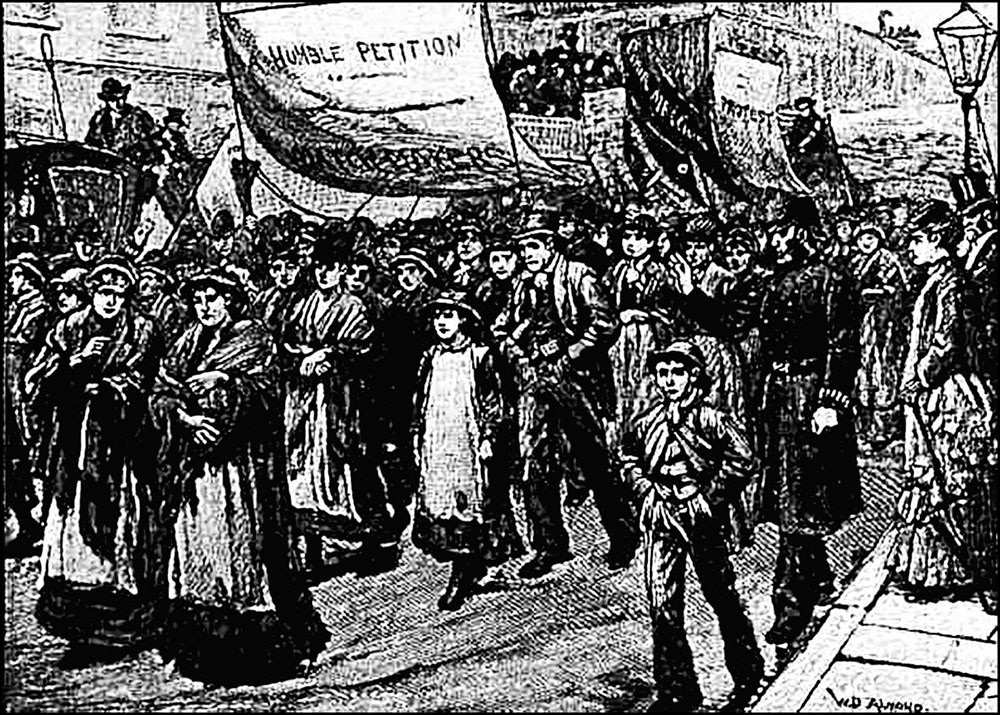

Women could be found in several hazardous industries. They might contract the respiratory disease byssinosis (Brown Lung), working in the carding rooms or loom sheds of cotton factories; but they were kept out of areas where cotton-dust levels were really high, which were all-male environments. Likewise regarding asbestos. These were factory environments, where sex-segregation was possible, not just to keep women away from most danger, but so that each sex could associate separately. The same was true at Bryant & May’s London match factory in the late-nineteenth century, where exposure to yellow phosphorus fumes in the stages of manufacture (mixing and dipping) led to the fatal poisoning of many of the completely male workforce. Women were not allowed anywhere near this, and merely boxed the finished product, in what was a correspondingly all-female environment. Although ventilation was an issue, it was mainly if instructions regarding hygiene were not followed that there was any major risk of contracting the condition known as ‘phossy jaw’ (necrosis of the jaw bone) which, if left untreated, might be indirectly fatal, but usually caused partial facial discolouration and a foul-smelling pus, that led at worst to disfigurement. Nobody called for action on behalf of the men, but in 1888 the women were spurred to the most famous strike in history by the prospect of massive public and media support organised for them by the leading social reformer Annie Besant. Evidently, women‘s physical beauty was of far greater public concern than the death of men (a view that seems to remain, given the long struggle by the mass of miners for compensation for terminal respiratory conditions). Again, the underlying story is of sex segregation. It was the existence of female single-sex zones within the workplace to partition women away from danger, that ironically led to spurious stories about working women being comparatively hard done by.

The 1888 Match Girls Strike was the most famous in history, even though the incidence of phosphorous poisoning among male workers was far worse

Women are perfectly capable of doing many dirty and/or dangerous jobs, as they have to do in wartime (though even then, the men do the heaviest ‘reserved’ work). There are always a few women car mechanics, plumbers, etc; as we‘d expect by virtue of the small percentage of women with ‘brain patterning’ along male lines. It may be that there are no remotely typical women in these jobs at all. It’s still the case that all of the very worst jobs - in terms of work environment, physical demands, promotion/redundancy prospects, stress, likelihood of injury or death and extra hours of work regarded as the norm to make up reasonable pay - are manned 95-100%. Women do not look for jobs that pay a bonus for being ‘dirty’ or ‘dangerous’ because for them it would be essentially pointless, as a biologically-based analysis reveals. But it’s the fact that they are jobs that tend to be held by men that seals it. It’s self-segregation of the sexes that underlies why many light-assembly factories have for generations employed either nearly all women or nearly all men, for reasons nobody can remember (rather, it was for reasons we are but dimly aware of).

* * *

Most women are in the lower echelons of the economy in a separate all-female labour market. This is so pronounced that this horizontal job segregation has no impact on the pay gap, which is produced by vertical segregation (differences in the position in the organisational hierarchy). This is reflected in the fact that male and female unemployment rates are almost independent of each other. As Hakim concludes, competition between male and female workers does not happen. Equal pay laws have nil effect on female unemployment, despite economic theory predicting that as women’s wages rise relative to men’s, then women would tend to become progressively less employable. This didn‘t happen, because women’s jobs were mostly segregated - largely self-segregated - from men’s.

The sexes together and confused in the workplace: teamwork, harassment and hazing

In the light of the voluntary segregation by sex in workplaces: is a mixed-sex work environment just a recipe for conflict, or do many or most people find that the sexes are complementary in this situation? When the sexes are forced to be together, does one sex stick together at the expense of the other? How does performance and commitment alter according to whether the workplace is all male, all female, or a mix?

We know to expect differences, because women are found to favour other women far more than they do men, and women can have membership of the female ‘in-group’, no matter how unconnected. This is in contrast to the kind of ‘in-group’ formation by men that particularly suits the workplace as a natural locus for male coalition building. This complements the research which suggests that whereas women tend to be more relationally inter-dependent, men tend to be so more collectively.

Answering her own question in a 2001 review article entitled Are Men or Women More Committed to Organizations?, Kim Malloy finds that the problem of commitment comes from mixing the sexes. Men in particular don‘t want to commit to the workplace when they are significantly in the minority, and tend to leave. Efforts to integrate the sexes actually worsens this problem. This is not because of the presence of women, but the lack of other men to compete against.

Men compete with other men, and instead of competing against women, show deference to them. After all, women are what men compete for. Women do not compete with each other on anything like the scale that men do, and suffer no social stigma in competing against men if they so choose. They can swap with impunity between competitive and sexual modes in their dealings with men, whereas men are severely constrained in reciprocating. Entrench this institutionally and politically, and no wonder men will be disillusioned in a workplace where female employees greatly outnumber them. They are at sea in the relative absence of others who are psychologically salient to them as competitors.

The Sugar Daddy

Viewers of the fascinating BBC television series The Apprentice, in which the businessman Sir Alan Sugar obliged teams of women and men to compete against each other (with the weakest performer facing dismissal) might well argue with the nostrum that only men are status-seeking. If anything the male team members were relaxed and co-operative and the women confrontational and status-obsessed. (And, although the producers of reality TV programmes deliberately select non-typical contestants, viewers will confirm that this was more genuine than the average reality TV freak show.)

How can this be? Men, being naturally task-oriented, are happy for their performance (and resulting position in their DH) to be determined by results. Just as in a game of cricket either you win or you lose, and most men - not just those who have gone to public school - are resigned to accepting the outcome with good grace (witness their relative lack of histrionics on receipt of Sir Alan’s catchphrase, ‘You’re fired’).There’s always another game.

Women, however - even high-flyers like The Apprentice contestants - when pitched into a task-oriented environment may fail to perceive that the outcome is all that matters (rather than the impact of the task on their social network) and so become obsessed by their perceived position - in other words they tend to psychologise something that men see in purely instrumental terms. This explains the paradox that women might superficially appear to be the most status-obsessed sex in the workplace despite men being much more strongly motivated in this regard. Men are not obsessed with status so much as achievement - status naturally following on from success.

The silly notion that men perceive women at work as some kind of threat, is just feminism-inspired wishful thinking. Men perceive nothing of the kind, even though in a particular important sense they would be quite correct if they did. Women network in a different way to men. They are much more co-operative in a personal sense, whereas men are cooperative as regards the task and can get on with people they don’t like. This means that the perception by women of actual achievements of fellow workers tends to be subsumed under personal considerations, and ‘relational aggression’ may result in social ostracism. Again, this is the reverse of the popular fallacy of an all-male club. Men co-operate as an alliance to serve competition, and this can easily be focused on a task, which is why men function well in organisations. Women co-operate so as to form a gossip circle. First, to ‘find out’ men - the minority of winners and majority of losers in their eyes; and second, to assort to some degree amongst themselves. Achieving things outside these social concerns - not least the tasks to be done in the workplace - is something female co-operation can be co-opted for, but is some distance from the reason for its existence.

The reality is the opposite of ‘male chauvinism’. Women, not men, club together in this way (male coalitional behaviour being a different phenomenon). And women, not men, treat members of the opposite sex unfavourably. After all, women sift through men and very reservedly choose a man as either a long-term sexual partner, or - if he is rather more extraordinary - as a one-instance sexual liaison. Men are radically different, being open to virtually anything with any and almost every woman if sex is a prospect, however far removed or unlikely. In ordinary social life, this translates into women taking good care to keep at a distance from many or most men, and they do this both individually and collectively.

* * *

At work, the most extreme potential flashpoint, obviously, is when sex becomes salient as actual sexuality. Women inevitably have to brush off advances, which normally they not only take in their stride, but as compliments that help them to choose between men. Problems come when a woman lacks resourcefulness, and/or is politically encouraged to pretend likewise, to deal with this normal part of life. Now that we have the bizarre nurturing of woman as social moron in the legal wormhole of a harassment charge, the small number of genuine cases of sexual harassment are lost under an avalanche of the trivial or bogus, that would be of no issue were it not for a precautionary principle deeming them worthy of investigation - to avoid being sued, and to satisfy over-zealous corporate or statutory ‘equal opportunities and diversity’ policies.

By enacting legislation focused on the often false perception of the supposed victim (Sorenson & Amick, 2005) rather than the intention of the putative assailant, the law is being used to misrepresent and criminalise normal interaction. So what is going on when flirting becomes harassment? Generally, a man who appears a skilful flirt is actually simply a man sufficiently high in status to attract the woman he is flirting with, and for that reason can keep her interest, and even get a date. At worst, he’ll get a reputation as a ‘bit of a card’. A man who instead appears simply to be unwelcome in his attentiveness is usually just a man insufficiently high in status. This will trigger in the woman her ‘cheater-detection’ mechanisms, that will cause her to perceive the man in various unwarranted negative ways, and he‘ll fall foul of the gossip network. Even if his attention is just genuinely friendly playfulness with little real sexual intent; for a slight lack of judgement of respective ‘mate value’, the man runs the very real risk of a criminal charge.

However, matters seem to be more complicated than this in the workplace. We would expect that here women interact both through their personal network - their normal mode of interaction - and through the work hierarchy, in which they are in effect acting as surrogate males - part of the (male) dominance hierarchy. A woman places herself, or has been placed, in a situation that she can use to her advantage, but which is also a potentially compromised position, whereby a man can take advantage of her position in the work hierarchy rather than to engage with her through her personal network. If a woman perceives a man’s approach to her as being not through her personal network but as being within the status hierarchy, then she may interpret this as harassment. This is a measure of how out of kilter a social network organisation is when placed within a hierarchy.

This analysis reflects just what researchers have found. Women don’t feel harassed when ‘hit on’ by high-status compared to low-status men when they are outside work. We can interpret this as being because there is no confusion in a woman‘s mind between personal network and hierarchy. At work they actually feel more harassed when ‘hit on’ by a high-status work colleague than by a lowlier-one (Bourgeois & Perkins, 2003). And this would seem to be because here they are confused between their natural and surrogate roles (in the workplace DH).

A man cannot second-guess the distinction women intuitively make. It’s bad enough that a man is saddled with the cost of misjudging the relative ‘mate value’ whenever he makes a sexual approach. But here, even if he makes a non-sexual approach, he may still be accused of harassment. Furthermore, because a dominance display is part-and-parcel of a sexual approach (the evolutionary process having co-opted dominance signalling for courtship), then the normal behaviour of a work superior could be easily misconstrued as harassment. This is transparently an unfair position for men to find themselves in.

* * *

Another and far more common source of confusion for the sexes interacting in the workplace is when the usual ways that people get along with others of their own sex crosses the sex boundary. The universal way that human males carry on is by ‘winding each other up’ - men always do this to find out if a new recruit is trustworthy, how clued-up and socially skilled he is, and if he is interested enough in being there. A series of tests are used to make sure someone is worthy of being admitted to the ‘in-group’.

In a male single-sex environment, new recruits in many establishments get ‘initiated’ or hazed (to use the American expression), especially when bad teamwork would be life threatening - notably in mining and the armed forces. Notwithstanding the occasional excess, it’s a very pro-social phenomenon, and most men in most situations where it occurs have little trouble enduring what is an acceptance ritual into a new coalition. Traditional craft apprenticeship, street gang and college fraternity initiation rites can also be understood in this way.

Winding each other up is a highly constructive form of harassment, as Warren Farrell analysed (Farrell, 1994). It de-individualises men to prepare them to sacrifice themselves for the survival of the group (especially the survival of the women in the group), or even for no better reason than that they just became an unproductive burden. This is quintessentially male and quite alien to women. Not just team- orientated, men are also task-centred more than they are relationship builders; and hazing is about whether you are up to scratch rather than how you click with other people. But it’s a joining ceremony, and about inclusion, not exclusion - on certain terms, and likely not a favourable place in the informal hierarchy; but inclusion nonetheless.

There is no equivalent in female single-sex workplaces, though it may appear that there is a more subdued version. Women do not have to offer themselves as sacrifice for anybody (except perhaps their own children), and don’t form teams of those at hand, and nor do they tend to be orientated to the task. So here recruitment is simply into a gossip network of individuals that extends well beyond the group of women on site. This is so open that initiation would hardly be needed.

Neither of these scenarios fit the bill when the opposite sex is also recruited, because neither team-building nor personal networking can be applied, and the whole workplace culture can be damaged. Women know that in places where men predominate they might get wound up by the men - suspicious that women are getting a better, cushier deal from management at their expense. Such disparagement would not be unfounded: the women cannot be tested out as they would be if they were men, and (as men know all too well) women can hop between a work role and natural sexual mode according to what is advantageous for them. Men get a considerably harder time than this if they go for work labelled ‘woman’s’, as some men have done following on the closure of heavy industry.

What might happen to a woman in an otherwise male work environment? There would be engagement with her, not least because a woman is invariably of interest to men. Men always bring women in to their ‘in-group’. This gets round the problem of trying to get along with someone who, being a woman, cannot be assimilated normally by male team building. In that the male style of team building would be more likely to be inclusive than the female personal network, she may somehow be coopted, with the woman treated in some respects as an ‘honorary male’. But perhaps the men would be in two minds whether to view her in this way or to display to her. A mixture or an alternation of mild hazing and mild flirting could be a dangerous cocktail for the male team members though. Men would realise this, and be accordingly stand-offish.

A woman on the receiving end of this might read sexuality into what is mild hazing alongside flirting or simple friendliness, and then - given how easy it is to do, and the encouragements on offer - may initiate a harassment charge purely on the basis of her own misperceptions, regardless of the innocent intent of the man she accuses. This destroys teamwork and may even result in a team builder losing his job, whilst the socially incompetent woman retains hers. It would not take much of this before eventually the whole organisation would be unable to communicate internally about anything.

The stakes have been raised by legal precedents and, since 1997, an EU directive which makes employers liable if for any reason they fail to protect an employee. The onus of proof is entirely on the employer, who then has no choice but to side with the complainant, leaving the falsely accused isolated. Once again, codified in law is a subjective flexibility for a woman rather than an objective rule by which people can know where they stand. The absurdity is complete with the general adoption into codes of practice by organisations and firms of the notion of harassment as anything considered as such by either the recipient or any witness. Yet more disturbing still is the incorporation of this ‘principle’ into law.

Meryl Streep and Anne Hathaway in The Devil Wears Prada (2006)

Women tend to revile women bosses

It might be expected that, with the separate social organisation of the sexes, having a boss of the opposite sex might be problematic, and that with women sticking together the most benign arrangement is women working for a woman boss. Paradoxical though it seems, nothing could be further from the truth. Organisations function best where bosses are male - whether their underlings are male or female - and worst when bosses are female. They function worst of all when a woman manages women.

Research reveals that women overwhelmingly prefer not to work under another female. This is a profoundly negative feeling about women as line managers and not a positive feeling about men in the role. A useless male boss is preferred to a competent female one. It’s not just an issue of women not liking working for women superiors, but that they don’t want to cooperate with or even acknowledge them (Molm, 1986). Some female secretaries actually walk out of recruitment when they find that their prospective boss is a woman. (The squabbling on The Apprentice came to a head when Miranda Rose got the boot for disloyalty after being appointed P.A. by the power-hungry Adele Lock. The job appeared to have no purpose other than to improve Ms. Lock’s level of self-esteem and had disastrous consequences for the female social network as well as for the ‘enterprise’.) A survey for the Royal Mail in 2000 reported that only seven percent of women preferred a female superior. In a 1991 survey, of women who had worked through the Alfred Marks agency under both men and women, less than a fifth said they would want a woman line manager in future, and two-thirds said they would never work under a woman again and wanted their boss to be male. Almost the same proportion (three in five) expressed just the same to researchers for Harper’s Bazaar magazine in 2007 - and these were professional women in top jobs.

Women’s unwillingness to work for a woman line manager is greater compared to men’s (Mavin, Sandra & Lockwood, 2004; Mavin, Sharon & Bryans, 2003). Women can positively welcome work beyond their job description when it’s for a male boss. However hidden, it appears that a sexual frisson - which can be very widely manifested, in many not overtly sexual ways - makes a dull job sparkle. Inter-sexual social reality is what is most salient.

Women complain that female bosses have favourites and are inconsistent because they deal in personal relationships instead of focusing on the job, whereas women feel they get fair treatment from male bosses. The predominantly personal dimension of women’s managerial style leads to sniping or awkwardness; or a sense of superiority and trying to prove a point when giving out work.

Something powerful is at play here. Women have an acute awareness of the separate worlds of the sexes. Underlying the negative feelings women have for same-sex bosses, is that they are aware of the instrumental motivation of women to try to travel up organisational structures, of being more in the company of higher-status men. From the perspective of evolutionary psychology, women don’t acquire status, except in the sense of acquiring it indirectly from their long-term mates; so women placing themselves over other women according to the criteria of a male competitive status hierarchy may be seen by their female underlings as incongruous - cheating even. Women’s natural predisposition to networking exacerbates this. A female boss is not centred on the workplace as a coalition as are men; instead being more concerned with what she perceives as her ‘in-group’ of women, most of whom are likely outside the organisation, with whom the women under her may well have no connection.

The women bosses with their favoured women underlings stick together, and the selective bias women have for other women will come out in interviews for promotion. There is an irony that women, as the people women least want to see manage them, will tend to end up with positions of responsibility, thus driving further workplace discord amongst women, and further discrimination against men.

Women’s preference for their own sex: serious sex discrimination against men

The fourfold female preference for their own sex, and the ‘in-group’/‘out-group’ differences between men and women (see chapter four) means that employers entrusting recruitment to women are likely to get not the best man for the job but more likely a mediocre woman. It also means potential problems of female performance in the job, irrespective of ability. The upshot for men is serious sex discrimination against them.

In recruitment, whereas women candidates will tend on average not to suffer discrimination - even if the interview panel is all-male - men candidates will probably suffer worst outcomes the greater is the proportion of female interviewers. If the panel is all-women, then not only is this effect at its maximum, but there is no male perspective to counteract it. Women interviewers will prefer women (even aside from any feminist political attitudes, or any acceptance of notions of supposed oppression of women, or pressure through equal-opportunities policies). There would seem to be two complementary reasons for this. First, the interviewer tends to feel a potential personal connection with any and every female applicant, even though she may be a complete stranger - there need be no shared ‘in-group’ for this to occur, as would be the case for men. Second, prejudicial preference will go relatively unchecked (compared to how men would feel) given that women have a very different sense of ‘in-group’, and so will be less concerned about the impact of making a decision that may not be in the best interests of the work group.

I encountered this when I first applied for a lowly job at the Home Office. The all-woman interview panel rejected me, ostensibly - and, to say the least, ironically, given future events - for lack of ‘communication skills’. It turned out to be a case of a mismatch between male and female communication styles, with my use ‘in inverted commas’ of two colloquialisms one interviewer labelled ‘swear words’. (Ten months later I had another interview for a job in another part of the Home Office, but this time I faced a lone female, and not from HR but an ordinary worker. Evidently I ticked too many boxes for them to fail me a second time.)

Regarding internal interviews for promotion, the problem is still worse, because by now the female interviewee may well be within the female interviewer’s personal network.

Performance in the job by female workers will tend to be problematic because of the relative failure to identify with the ‘in-group’ of fellow workers, and to focus instead on personal connectedness rather than the task at hand. This will reduce efficiency in the workplace directly, but there is also a further impact in that those members of the work group that the top clique of female workers do not feel personally related to, will feel rejected. As a result, they will either become de-motivated, or work more for themselves and competitively against the group. This is the opposite of how male workers would tend to behave. Men experience a mutually reinforcing sense of belonging to a group, and competitiveness on behalf of the group (as well as individual effort within it to try to rise to the top).

The current notion though, is that women make better employees than men. Men are thought to be ‘bolshy’ and women compliant. Yet the more rule-based existence of men - apparent right from the days of school playground team sports - makes them likely to be more predictable and reasonable than women. Countless television advertisements (exemplified by the excruciating BT ‘work smarter’ series, but long ubiquitous), proclaim a contest of male ‘dimwits’ versus female ‘smarties’. In fact, the average intelligence difference of five IQ points is in men’s favour, which is amplified by the male sex-typical distribution (see chapter five). The problem is female mediocrity, which appears virtuous and high-achieving, especially by contrast to how men are seen, because of the prejudices born of the social psychology of ‘cheater detection’.

Some think that men are too status-orientated, without seeing that there is a problem with women employees of being too person-centred. Both male and female sex-typical behaviours could be regarded either as distractions from or contributions to the work culture, but employers certainly do prefer women (as a 1996 Rowntree report showed). Yet it is men who have the additional clear attributes of being both task-centred and of forming teams within the workplace, rather than personal networks that may well be more connected with life outside - though sometimes female work teams are as effective as male ones. Currently, there is a misperception that inter-personal facility necessarily makes for constructive co-operation, and that relational aggression makes for fruitful competition.

* * *

Conclusive evidence of widescale discrimination against men at the job application stage was uncovered in 2006 by Peter Riach and Judith Rich (An Experimental Investigation of Sexual Discrimination in Hiring in the English Labour Market). They had sent pairs of résumés to employers: one from a mythical applicant called ‘Phillip’ and another from a no less fictitious ‘Emma’, differing from each other only in the most minor details, but sufficient to ensure they would not be detected as being identical. The experience, qualifications, age, marital status, socio-economic background - every relevant detail - were as near to identical as could make no difference. They awaited the offer of an interview (or a request for a telephone discussion) or a rejection note (or silence).

Nobody was prepared for the result. Not even the direction of it, let alone the size. It was not women but men who got the fewer offers, and by not a small margin but by a massive factor of four. Uncannily, this is precisely the same factor by which women prefer other women to men, as discovered in research into the female social psychology of ‘in-group’. Have workplaces completely capitulated to basing their hiring entirely on female prejudice? (HR is a predominately female profession.)

If the fourfold disparity was not startling enough, compounding the surprise were the job sectors where this applied. The persisting problem of serious discrimination against men trying to get secretarial jobs was found thirty years ago in the USA (Levinson, 1975), and it was at almost exactly the same level as it is today - applications being twice as likely to be rejected. It was and is much harder for men to get accepted into ‘female jobs’ than for women to get in to ‘male jobs’, even though in content they are ‘gender neutral’. There are two reasons for this. ‘Female’ jobs are more to do with sex-typical aspects than are their ‘male’ counterparts; and men are perceived as odd to be going for a lower-status ‘female’ job, whereas women are not in any way looked down on or viewed as deviant in applying for a ‘male’ job. This is because only men are judged in terms of status. This world of female sex-typical work carries on as if in a previous age. Jobs are advertised in magazines like Girl About Town using key words like ‘bubbly’ and ‘vivacious’, and obtained through agencies such as Office Angels. Employers relate that agencies ring up and ask: ‘I’ve got a gentleman for you; will that be all right?’.

It’s common knowledge that sexism towards men remains rife in female sex-typical jobs like the secretary, but nobody would have thought that this extended to professional work, but this was the focus of Riach and Rich’s research. The shock is that there is now even more discrimination against men in male sex-typical jobs: and in the higher-status professional jobs, at that. This is notably in accountancy, and also in what is possibly the most obviously male sex-typical work sector of all - information technology - and in the very niche within this which is most so: the job of computer programmer/analyst. This may well have something to do with the fact that the numbers of women in IT, that were never high, are now declining.

The study’s authors point out that their findings are consistent with all previous research that shows that the vast bulk of discrimination occurs at the invitation to interview stage. This preferential choice of women for interview is clearly ‘affirmative action’, which is illegal, and could see many occupations becoming ‘female-dominated’.

Employers must now not merely ignore the problems they are likely to experience with women employees - maternity, greater sickness absence, and a less committed attitude to work, the workplace and to colleagues that recent research shows - but perversely preferring women in spite of them. It’s not that employers have objectively recognised women to be better than men. In the absence of objectivity there is only prejudice.

There may also be damage limitation. Those who run small- to medium-sized businesses complain that they are not in a position to decline female applicants, because they simply cannot afford the cost of employment tribunal cases for sex discrimination. It’s easy for a woman to bring a case of little if any substance, with an easily-made prima facie argument at no cost to themselves, but at crippling cost to employers regardless of the outcome. It could be that in larger organisations, this consideration, allied to a desire to engage in ‘positive action’, significantly exacerbates the prejudice towards men to account for the scale of sex discrimination against them.

* * *

Men are starting to do something about discrimination against them - reluctantly, as usual - and now make up more than half of the complaints about discrimination. There have been high-profile and blatant cases that raise public awareness - such as at BT and the US cosmetics firm which refused to promote or even to employ men. But through the usual prejudices, these have been quickly forgotten.

The laws on sex discrimination may have started to break down some anti-male barriers, but there is abuse of sex-discrimination law itself, whereby women can actually avoid being treated equally to men, and instead be given special favour. This was exemplified by an Employment Tribunal case in 1990 when a civil servant, Mrs Meade-Hill, sought to be exempted from the ‘mobility rule’ whereby anyone on her job grade may be required to relocate. Her argument was that as a secondary earner to her husband, she would have to get his agreement, which was unfair compared to a man in a similar situation. As the salaries of wives are typically much less than their husbands’, then it was considered that her situation fell under ‘indirect’ sex discrimination. She won. This was despite her job paying a primary earner’s salary - as shown by half the staff being male - and despite the ‘mobility’ rule being apparently no problem for women staff - as shown by the other half of the staff being female.

The point is that the ‘mobility rule’ is no less resented by men, who could with equal or even more force argue that their wives as mothers were firmly rooted and also the key decision-makers in the household, making it impossible to move.