HIS FULL NAME WAS PHILIPPOS AMYNTA MAKEDON, THAT IS, PHILIP, son of Amyntas, the Macedonian. He was born in the year 383, and became famous as king Philip II of Macedonia, the king who re-organized his country and built it into a great power dominating Greece and the Balkan region. Yet he can have had little expectation, when growing up, of ever ruling his native land. His father Amyntas was ruler of Macedonia for some twenty-four years (393–370), but Philip was only the youngest of three sons of Amyntas by his wife Eurydice: his two older brothers, Alexander and Perdiccas, had prior claims to succeed to their father’s power. In addition, in the polygamous tradition of Macedonian rulers, Amyntas also had three more sons by another wife named Gygaea: Archelaus, Menelaus, and Arrhidaeus. The likelihood of the young Philip ever succeeding to the position of ruler must have seemed remote—but not impossible. For during the opening decades of the fourth century, as we have already seen, Macedonia went through a series of succession crises and disputes, during which any descendant of the foundational ruler Alexander I could—and many did—make a claim to the rulership. As a member of the Argead ruling clan, then, and a descendant of Alexander I, the position of ruler was always a possibility for Philip; but as the youngest of three brothers, and to all appearances a loyal brother at that, he must have expected to play a secondary role. And the weakness and instability of Macedonia, and of his father’s rule, can have done little to encourage high expectations.

1. THE REIGN OF AMYNTAS III

Amyntas’ rule of Macedonia was interrupted on at least two occasions: around 392, shortly after he came to power, and around 383/2, just about the time of Philip’s birth. The details are sketchy and murky, like almost all of Macedonia’s history before the reign of Philip, and historians have debated endlessly whether and when and by whom Amyntas was driven from power and restored to power. The key evidence comes from the historians Diodorus and Xenophon, and while those two often disagree about the course of events, in this case their accounts are most likely complementary.

Diodorus tells us that shortly after Amyntas came to power, Macedonia suffered an Illyrian invasion which drove him out of the country entirely (Diodorus 14.92.3–4). He reports that, in an evidently futile attempt to gather enough support to hold onto his kingdom, Amyntas ceded border territories in the east to the Olynthian League. This is generally assumed to refer to the region of Anthemous in the north-west Chalcidice, though some scholars think rather of the Lake Bolbe region to the east (see map 1). Either way, it seems the grant was intended to be temporary, in return for some sort of aid. If the aid materialized, it did not work. Amyntas was forced to leave Macedonia, and was only restored to power some time later thanks to Thessalian help, presumably from the Aleuadae of Larissa in northern Thessaly, long-time allies of the Argead kings. Further Diodorus states that some sources alleged that another ruler named Argaeus held power in Macedonia for two years at this time: we are perhaps to imagine that he was installed with Illyrian support, since the Illyrians apparently dominated Macedonia at this time.

Who exactly this Argaeus was is unclear, except that he must have been an Argead descendant of Alexander I to be able to claim power. The name Argaeus is attested earlier in the list of Argead kings: the second ruler, after the founder Perdiccas, in Herodotus’ king-list was so named. Indeed, the clan name Argeadai presumably derives from the name Argaeus, meaning descendants of Argaeus—rather than the meaning “men from Argos” as implied by Herodotus’ story of Argive origins for the clan. Since Argaeus was to make another attempt on the Macedonian throne nearly thirty-five years later, in 359 (as we shall see), he must have been rather a young man at the time of his first period in power, or pretending to power as the case may be. Perhaps we should see in him a younger brother or son of Amyntas the Little, descending from Alexander I via Menelaus. The fact that he evidently ruled, to the extent that he did rule, under Illyrian patronage, will hardly have endeared him to the Macedonian aristocracy and people, however.

The Illyrians normally constituted more of a threat to raid and pillage upper Macedonia, rather than to occupy and dominate the realm. A loose agglomeration of separate, and at times mutually hostile, tribes inhabiting roughly what is now central and northern Albania, Montenegro, and parts of coastal Croatia, the Illyrians are little known to history: they produced no records of themselves, and are mentioned by our Greek sources only rarely and tangentially. Usually, split into numerous tribes and clans, they were no more than a nuisance to their Greek-speaking neighbors to the south. But at times a tribal leader of more than usual ability might succeed in uniting behind him enough of the tribes to become a regional power, and that is what happened in the 390s as a remarkable leader named Bardylis won control of much of Illyria. Bardylis ruled over the Illyrians for nearly forty years, from the 390s until the early 350s, and was powerful enough to pose a serious threat to Macedonia on a number of occasions. The first such occasion was his invasion of Macedonia in about 392, driving Amyntas III out and allowing Argaeus to rule at least part of Macedonia for a year or two.

When his Thessalian allies finally enabled Amyntas to recover the core part of his kingdom, probably in late 391 or early 390, he was able to drive out Argaeus and win back the support of most Macedonians: the Macedonians certainly objected strongly to Illyrian domination, and so to a ruler supported by Illyrian power. But he was left with two intractable problems: how to maintain himself against further Illyrian pressure, and what to do about the Olynthian League which now controlled part of Macedonia. On his own, Amyntas lacked the power to deal with these two threatening neighbors effectively, and his Thessalian allies had preoccupations within Thessaly. Amyntas was forced to negotiate with the Illyrians: in order to prevent another Illyrian invasion he was obliged to pay tribute to the Illyrian ruler. Buying off foreign enemies in this way is known to historians of early England as “paying the Danegeld,” after the tribute moneys sent by Saxon rulers to buy off their all-too-powerful Danish neighbors in northern Britain. As the Saxons discovered, the problem with “paying the Danegeld” is that the Danes always come back for more: it is not a satisfactory solution, and Amyntas was to find the same. But he had, in his weakness, little choice. To cement his agreement, most likely, Amyntas married an Illyrian wife, the daughter of an Illyrian chief named Sirrhas. Her original Illyrian name is unknown: she adopted a Macedonian name, Eurydice, and became the mother of Amyntas’ sons and successors. The oldest son of this marriage, Alexander, must have been born by 388 at the latest, as he was an adult able to assume rule of Macedonia at his father’s death in late 370.

Having, for the time being, successfully bought off the Illyrians with tribute money and a marriage alliance, Amyntas needed to bolster his support within Macedonia. One of the most powerful men in Macedonia at this time was the head of the dynastic family which dominated the upper Macedonian canton of Elimea, Derdas. Known to us from southern Greek sources, Derdas controlled a cavalry force as large and of as good quality as that of Amyntas, and interacted with southern Greek powers at times as an essentially independent ruler. It has been suggested that it was Derdas’ support that helped Amyntas III seize power in the first place, that is, that the assassinations of Amyntas the Little by Derdas and of Pausanias by Amyntas III Arrhidaeou were part of a concerted plan to make Amyntas Arrhidaeou ruler. At any rate, good relations between Amyntas and Derdas are attested in this period, and with Derdas behind him, Amyntas had at least one solid base of support for his power. But he likely felt the need for more.

It may well have been at this time, then, that Amyntas entered into his second marriage, with the intriguingly named Gygaea. The name is attested as being used in the Argead clan: a sister of the foundational ruler Alexander I was named Gygaea, suggesting that Amyntas’ new wife may also have belonged to the clan. Indeed it has been suggested that she was the granddaughter of Alexander I’s son Menelaus, though it is not clear on what basis. If correct though, she may have been a daughter or niece of Amyntas the Little; and the marriage was likely intended to heal the breach between rival branches of the Argead line, shoring up Amyntas’ support within Macedonia. That the marriage belongs to the period of the early to mid-380s seems likely based on the likely time of birth of the oldest son of the marriage, Archelaus. Since Alexander, son of Eurydice, was able to succeed his father Amyntas in late 370 without opposition, he seems likely to have been the oldest son. Gygaea’s son Archelaus did eventually seek the rulership, but not until after the death of Eurydice’s second son Perdiccas in 360, as a rival to Eurydice’s third son Philip. Perdiccas was likely born about 385. It seems plausible that Archelaus was born about the same time, perhaps slightly later than Perdiccas, and so was old enough to mount an attempt at the rulership only after Perdiccas’ demise. That would likely place his parents’ marriage around 387 to 385, and would make sense in light of Amyntas’ need to win internal support in Macedonia at that time. For having settled matters, for the time being, with the Illyrians, he needed to deal with the threat posed by the Olynthians.

We have seen that under the threat of the Illyrian invasion ca. 392, Amyntas had ceded borderlands in the northern Chalcidice to the Olynthians in the hope or expectation of Olynthian aid, which either failed to materialize or was ineffective, as Amyntas was in fact driven out of Macedonia by the Illyrians. Restored to power in Macedonia by his Thessalian allies, Amyntas made a treaty with the Olynthian League, part of which survives in an inscription: both parties agreed to help each other against future attacks, and both agreed not to make any deals with three named Greek cities in the region (Acanthus, Mende, Amphipolis) or the Bottiaeans, without the other party’s consent; in addition the Chalcidians of the League received certain rights to import timber and pitch from Macedonia. The treaty seemed to favor the Olynthian League, and the Olynthians continued, as Diodorus tells us, to control and enjoy the revenues of the land that Amyntas had ceded under Illyrian pressure back in 392. When Amyntas now, in about 384/3, feeling more secure in Macedonia, attempted to redress the balance of power with the Olynthians and win back the ceded territory, the Olynthians responded by driving Amyntas out of eastern Macedonia and capturing various Macedonian towns including the new capital Pella, already the largest city in Macedonia. All this is reported by Xenophon, who alleges that by late 383 Amyntas had effectively lost control of his kingdom (Hellenica 5.2.12–13; 5.2.38).

It was at this low point in Amyntas’ career, then, that Philip was born, the third of Amyntas’ sons by Eurydice, but probably his fourth or fifth son overall. Amyntas in fact survived the Olynthian threat that confronted him at the time of Philip’s birth by appealing to the Spartans. In 386 a general or common peace had been agreed to throughout the Greek world, under pressure from the Persian king Artaxerxes II and overseen by the Spartans. By this so-called King’s Peace, all Greek city-states were to be mutually free and autonomous, and the Spartans saw to the enforcement of this condition. In 383, the Olynthians as leaders of the alliance of city-states in the Chalcidice generally known as the Olynthian League were pressuring as yet unaffiliated cities in the region to join. Two of these cities, Acanthus and Apollonia, sent embassies to Sparta protesting this Olynthian pressure, and calling on the Spartans to enforce their right to freedom and autonomy by forcing the Olynthians to leave them in peace. The Acanthian envoy, according to Xenophon, illustrated Olynthian ambitions and the danger to the King’s Peace (and Spartan predominance in Greece), by describing how the Olynthians had virtually driven Amyntas from his kingdom and seized control of Macedonia, and alleging that Sparta’s perennial rivals the Athenians and Thebans were preparing to ally with the Olynthians. The Spartans decided to act, and in 382 war ensued between the Spartans and the Olynthian League.

This war was a godsend to Amyntas, who sent an embassy of his own to Sparta, according to Diodorus (15.19.3), further urging the Spartans to action. To prosecute the war, the Spartans sent a large infantry force to the Chalcidice, and allied with Amyntas and his friend Derdas in order to obtain cavalry. Derdas’ cavalry, in particular, gave an excellent account of themselves and, though the war proved more difficult than at first anticipated, the Spartans did in the end win: in 379 the Olynthians were forced to capitulate. They had to disband their alliance system, and Amyntas gained back his lost territories. Of course, freedom from the threat posed by the Olynthian League might have been off set by uncomfortable pressure from the new power in the region, the Spartans. But Amyntas was spared this by a new development in southern Greece.

Between 379 and 377 the Athenians, encouraged by their allies the Thebans, founded a new alliance system aimed at forcing the Spartans to stop meddling in the affairs of other Greeks, that is, to reduce Spartan predominance in Greece. This Second Athenian Confederacy, together with the Thebans, was soon at war with the Spartans. As a result the Spartans spent the 370s campaigning on land in Boeotia against the Thebans, and at sea against the Athenians, leaving them unable and unwilling to interfere further in the north. However, Amyntas was not to be left entirely in peace. The renewal of Athenian naval power led to renewed Athenian demand for Macedonian timber for ship-building, and renewed Athenian pressure to control the ports on Macedonia’s coast, in particular Methone and Pydna. Thus the demise of one threat to Amyntas led to the rise of another.

Amyntas responded in the only way he could: he abandoned his alliance with the Spartans and instead negotiated a treaty with the Athenians, seeking at least to control the Athenian threat by making concessions. Macedonian interest in Amphipolis—the crucial former Athenian colony at the mouth of the River Strymon—was ended, and in 371, at a general Greek peace conference, Amyntas went so far as to recognize formally the Athenians’ claim to that city. Amyntas adopted the great Athenian general Iphicrates, a man whose strong connections in Thrace could help Amyntas in that quarter, as well as in his native Athens. The adoption was purely pro forma, but it illustrated Amyntas’ need to placate the Athenians. So too did the sending of a large consignment of ship-building timber to the Athenian statesman Timotheos in the late 370s. Diodorus also reports that, abandoning his long-time alliance with the Aleuadae of Thessalian Larissa, Amyntas agreed to a treaty with the rising new power in Thessaly, Jason of Pherae, in this same period of the late 370s (Diodorus 15.60.2). It is likely also in this period of the mid to late 370s that Amyntas formed a marriage alliance with another important Macedonian baron, Ptolemy of Aloros, who received as his bride Amyntas’ daughter Eurynoe. The need to shore up his support within Macedonia was still strong.

In late 370, finally, Amyntas died, apparently of natural causes, since no source alleges any violence, and his oldest son Alexander succeeded peacefully to his power, initially at least. Philip was about thirteen years old at this time. Amyntas was probably no more than sixty when he died, by no means an old man, given that his sons were (all six of them, it seems) under twenty. His reign had been a study in survival over weakness. Threatened several times with expulsion from his power, he had clung to his position as ruler thanks to the support of powerful but potentially threatening Macedonian barons such as Derdas and Ptolemy, to tribute payments sent regularly to keep the Illyrians away, and to alliances from a position of weakness with outside powers such as the Olynthians, the Spartans, the Athenians, and the Thessalian Aleuadae and Jason. Amyntas was clearly a clever and versatile man, and when necessary a persuasive one, but he was never able to muster the strength to begin to rebuild the improvements within Macedonia begun under Archelaus, let alone to advance Macedonia from its long-time role as a second- or third-rate power dominated by its neighbors.

2. YOUNG PHILIP

This chapter is entitled “Philip’s Childhood,” yet it may have been noticed that so far very little has been said in it directly about Philip himself: there has been much contextual discussion of the reign of Philip’s father and of conditions within Macedonia in particular and in the broader Greek world, but no description or anecdotes about Philip’s own life and experiences growing up. This reflects, it must be said, the state of our sources, unlike in the case of Philip’s son Alexander, of whose childhood ancient writers preserved a considerable amount of descriptive material. Philip’s experience growing up in Amyntas’ Macedonia was, on the one hand, one of privilege as a son of Macedonia’s ruler, but on the other, one of chronic weakness and insecurity as Amyntas clung to power only by a series of agreements with stronger outside powers. But though we have hardly any direct testimony regarding Philip’s childhood, we can say in a general way what it will have been like. In all probability, Philip was born in exile, but the family was soon able to return to Macedonia, and it was in the new capital of Pella, built under Archelaus, that he grew up during the 370s. As the son of Macedonia’s ruler, however precarious that rule may have been, Philip certainly experienced luxury, receiving the best that was to be had in Macedonia by way of upbringing and education.

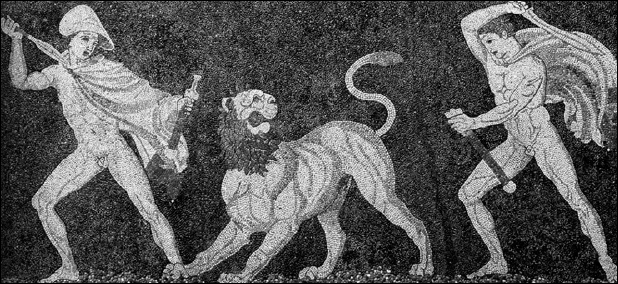

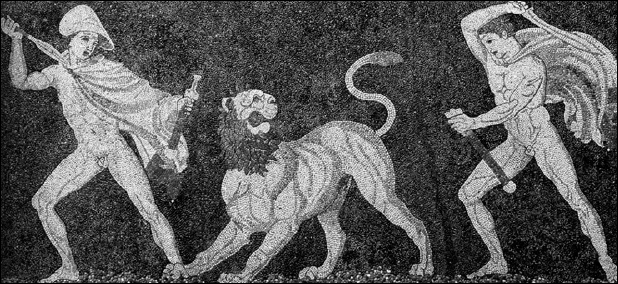

It was standard in ancient Greece for children to spend the first seven or so years of their lives in the charge of their mothers, and in the case of the wealthy and high-born also of nurse-maids and other servants. The real education of boy children began at about the age of seven, and involved their introduction into the world and concerns of men. In ancient Macedonia, that meant—for upper-class boys at any rate—a training in horse riding, hunting, and fighting; for upper-class Macedonians were hunters and cavalry warriors before all else. The hunting culture of the Macedonians is abundantly attested in literary and artistic media (see ill. 4), with the most dangerous animals being the most prized game, because to kill a dangerous animal was to show off one’s manly courage (andreia). So, for example, a Macedonian man had to prove himself by killing a wild boar without the use of a hunting net before he was permitted to recline on a couch at the traditional male dining and drinking parties. In the fourth century BCE, deer and boar were plentiful in Macedonia, and frequently hunted; but bear, panther, and lion were also to be found. The European lion (Panthera leo europaea) did not die out in the Balkan region until the first century BCE; lions and lion hunting are frequently shown in ancient Greek paintings and mosaics (see ill. 4). To hunt and kill a lion was of course the ultimate test of manliness. The great popularity of hunting at the Macedonian court is well attested in the time of Philip and his son Alexander, and it is clear that Philip grew up learning to hunt. The most notable depiction of this is perhaps from the royal tomb at Aegae that may actually be the tomb of Philip himself (though more probably of his son Arrhidaeus, also known as Philip III), on the facade of which is a magnificent painting depicting a hunt in which deer, a boar, a lion, and a bear are shown.

4. Lion hunt mosaic from Pella, Macedonia (in Pella Museum)

Wikimedia Commons public domain photo)

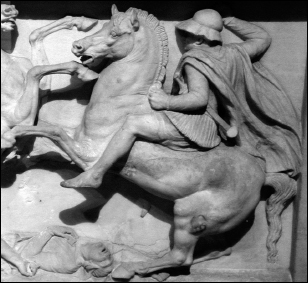

More important even than hunting was warfare, and the core of a young Macedonian noble’s upbringing was learning to ride and to fight from horse-back. Upper-class Macedonian youths were taught to ride from a young age, and learned also the skills of using the sword and the spear. Weapons drill included, in Macedonia, participation in special warrior dances, during which the dancers would twirl their weapons and engage in mock fighting. These armed dances of the Macedonians, mostly in honor of gods such as Heracles and Athena Promachos (Athena the “front-fighter”), patron deities of the Macedonian elites, are well attested: it was in fact at a performance of such dancing that Philip’s oldest brother Alexander was to be assassinated. As to horse-riding skills, ancient Greek horses were smaller than modern horses, and were ridden bareback (see ill. 5), using the thighs to grip the horse and maintain a seat on it. Thrusting with the spear or hacking with the sword required excellent grip and balance on the horse: a Macedonian rider needed strong legs, especially thighs. This training in hunting and fighting, then, was physically demanding and promoted a high degree of fitness and strength. Trained in this way, Philip enjoyed excellent health throughout his life, engaging constantly in extremely physically demanding pursuits and campaigns, and overcoming several life-threatening wounds.

5. Macedonian cavalryman (Antigonus the One-Eyed?) from the Alexander Sarcophagus (Istanbul Archaeological Museum)

(Wikimedia Commons photo by Marsyas)

Besides riding, hunting, and fighting, the upper-class Macedonian lifestyle revolved around the symposium, the male dining and drinking party. Upper-class Macedonian men were notoriously heavy drinkers (in the eyes of southern Greeks, that is), and like his son Alexander, Philip was no exception to this, as various stories tell us. Macedonian youths would first be introduced to the manners and customs of the symposium in their early teens, when they would act as servers and pourers (when slaves were not performing these tasks), and otherwise sit and observe. As we have seen, only when they had proved themselves in the hunting field did Macedonian youths graduate to full participants in the symposium. Since the symposium involved a great deal of singing, with the singer accompanying himself on the lyre, and conversation on many topics, including literature and philosophy (at the more high-class symposia at least), the young Macedonian noble was necessarily taught music—how to sing and play the lyre—and learned some of the classic songs of Greek culture by such greats as Alcaeus, Ibycus, Simonides, Anacreon, and others. And at the top level of society Philip inhabited, as a member of the ruling family, a basic education not just in literacy, but in the great literature of the Greek city-states—Homer, Hesiod, the great Athenian dramatists, history, philosophy, and rhetoric—will certainly have been provided. Philip famously hired the great philosopher Aristotle to educate his own son Alexander. As the younger son of a much less powerful and wealthy ruler, Philip himself was likely not educated at quite such a high level; but as an adult and a ruler we find that he was not just a well-informed man and a good speaker, but a patron of the arts welcoming philosophers, historians, dramatists, actors, and other notable cultural figures at his court, so it should not be doubted that he received a top-quality education.

All of this training and education did not happen in isolation: princes of the ruling family were normally provided with entourages of boys of their own age, drawn from the Macedonian hetairos class and called syntrophoi (literally, those reared along with one). We know of this practice specifically from the boyhood of Alexander, whose syntrophoi included various notable Macedonian nobles such as Ptolemy son of Lagos, Harpalus son of Machatas, Marsyas son of Philip, and most famously Hephaestion. These syntrophoi were educated alongside Alexander, also enjoying the teaching of Aristotle as a result. Just so Philip himself will have had his entourage of syntrophoi while growing up, providing him not only with companions, but crucially with a network of contacts within the Macedonian nobility. We can in fact guess at the identity of one of these syntrophoi: an exact coeval of Philip, born in 383/2, was Antigonus son of Philip, known to history as Antigonus the One-Eyed, founder (after Alexander’s premature death) of the Antigonid dynasty of Macedonian kings. Like Philip, Antigonus grew up in Pella, and he is reported to have been a companion of Philip throughout Philip’s career. Just as Antigonus’ much younger half-brother Marsyas was later a syntrophos of Alexander, so is Antigonus likely to have been of Philip. For all of his father’s difficulties, then, Philip evidently enjoyed a comfortable and excellent childhood and education.

Only one ancient source preserves an anecdote about the childhood of Philip, and unfortunately it only illustrates the historian’s problem in treating Philip’s youth. In a speech to the Athenian people about an embassy he had served on to Philip as king in 347, the orator Aeschines told how he had reminded the Macedonian king of the various benefits he, his family, and Macedonia in general had received from the Athenian people. Among these benefits, he says, was an occasion when the Athenian general Iphicrates saved the family of Philip from a rival Argead and would-be ruler of Macedonia named Pausanias. Amyntas and his oldest son Alexander II had recently died, Aeschines tells us, and Pausanias took this opportunity to try to return from exile to seize power, with most Macedonians supporting him. Taking advantage of the disorder in the region, the Athenians sent out Iphicrates with a small force to try to seize control of their former colony Amphipolis. When he arrived in the area, Philip’s mother Eurydice sent for him to plead for his help. This is how Aeschines painted the scene:

Then, I said, your mother Eurydice sent for him (Iphicrates) and, as all those present say, she placed your brother Perdiccas in Iphicrates’ arms, and set you—a small child still—on his knees, and said, “Amyntas the father of these little boys, when alive, made you his son and treated the city of the Athenians kindly, so it is proper for you both privately to treat these boys as a brother, and publicly to be our friend.” And she went on to make a strong entreaty both for your sakes and for her own, concerning the rule (of Macedonia) and concerning your safety in general. And hearing this, Iphicrates drove Pausanias out of Macedonia and saved the rulership for you. (Aeschines On the Embassy 28–29)

A very affecting scene, to be sure; but this anecdote cannot be true as it stands, despite the fact that Aeschines was a contemporary witness and alleges that he spoke these words to Philip himself. Quite simply, Amyntas died in 370, and Alexander II was assassinated in 369/8. That would place this scene most likely in the middle of 368. Philip, born about 383, was no small child then, but a youth of fourteen or fifteen, and his brother Perdiccas was at least a year older, sixteen or seventeen years old. Aeschines uses the word paidion to refer to the boys, meaning a child under seven years of age, according to the Greek Lexicon of Liddell and Scott. But Perdiccas and Philip were in fact not paidia at this time but teenagers, and the mind boggles at the image of Iphicrates with a sixteen-year-old youth in his arms, and another fourteen-year-old on his knees. In the homoerotic and pederastic culture of classical Greece, and classical Athens in particular, Eurydice’s reported action would have been tantamount to offering her sons for Iphicrates’ sexual enjoyment. In point of fact, at the time of Pausanias’ attempt to seize power, Philip was not present in Macedonia at all: he had been handed over by his brother Alexander to the Theban general Pelopidas as a hostage in 369, as we shall see below, and was living in Thebes.

One wonders what Philip made of these words, if Aeschines really spoke to him as he told the Athenians that he had. He must have been inwardly laughing at the claims made here, and at the fool that Aeschines was making of himself. We are left to wonder what to make of this story. Is any of it true? Iphicrates likely did in fact intervene to help Eurydice against Pausanias, but not in the manner or for the reasons Aeschines alleged. And if a man like Aeschines could so misstate things when speaking to Philip himself, and to a contemporary audience of Athenian citizens, what does that say about the rest of our sources? If the reader has been irritated at the frequency of conditionals, of such constructions as “may have” or “could have,” and use of the terms “perhaps” or “maybe” in this chapter, and at the lack of information about Philip himself, I trust that he or she will now understand.

3. THE REIGNS OF ALEXANDER II AND PERDICCAS III

Amyntas’ death, and the succession of his son Alexander II, came at a time of profound change in the power relations within the Greek world. In 371, the Athenians and Spartans, exhausted by war, had summoned a general peace conference in an attempt to arrange a “common peace” after the model of the King’s Peace of 386: a peace for all Greek states at once, guaranteeing all of them freedom and autonomy. The peace was agreed upon, but then came the process of swearing to abide by it. The Spartan king Agesilaus presided; the representative from Thebes, Epaminondas, attempted to swear on behalf of the Boeotian federation set up under Theban leadership (not to say under Theban pressure) during the 370s. Agesilaus refused to permit this: as in 386, he demanded that the Boeotian federation be disbanded, making each Boeotian community free and autonomous, and insisted that each Boeotian community must swear to the peace separately. Epaminondas (unlike the Theban representative in 386) refused this demand and left the conference without swearing. This meant a continuation of war between the Spartans and the Thebans, a war for which the Spartans were ready: an army some ten thousand strong, including around fifteen hundred Spartiates, was waiting in central Greece under the other Spartan king Cleombrotus. As soon as they had news of the outcome of the peace conference, Cleombrotus and his men invaded Boeotia from the north and marched to attack Thebes.

The Thebans too were ready. They mobilized an army in excess of eight thousand men and marched out under the command of Epaminondas to face the Spartans. The two armies met at a small town in Theban territory named Leuctra, and there occurred one of the most shocking upsets in military history. For more than two hundred years the Spartans had been invincible in any large-scale infantry battle: their expertise, prowess, indomitable courage, and unbeatable determination to conquer or die were legendary. Yet at the battle of Leuctra the Spartans were decisively defeated by Epaminondas’ Thebans, to the stunned surprise of the Greek world. After the battle, about seven hundred of the fifteen hundred Spartiate (that is, full Spartan citizen) warriors present lay dead, which was shocking enough. But far more shocking was that nearly eight hundred of them survived the battle, defeated and in flight. Spartans were not supposed to flee, to survive defeat: everyone knew the tale of the Spartan wives and mothers who handed their men, as they left for war, their shields with the words “come back with this, or on it”. Returning with one’s shield meant victorious; returning on one’s shield meant dead: the laconic words meant “conquer or die”.

What was the Spartan state to do with eight hundred men who had saved themselves in defeat by flight? According to Spartan law, they were now non-persons, stripped of citizen rights, denied access to their lands, their homes, to the sacred spaces of the Spartan communities, to be rejected and ignored by their families. But these eight hundred now represented more than half of all surviving Spartiates, for the number of Spartiates had dwindled over a hundred years of non-stop war to little more than two thousand before the disaster of Leuctra. The Spartan authorities were in a quandary: to follow the law would reduce the number of full Spartiates to just over than five hundred, not enough to think of sustaining the Spartan system and Spartan power; but how could they ignore the law they had lived by for two centuries and more? King Agesilaus, appealed to for his advice, solved the problem: the law was to remain in effect, from the next day. The disgraced eight hundred got a one-day moratorium, and were saved, to themselves and to the Spartan state. But Spartan power had taken a hammer-blow: the mystique of Spartan invincibility, of Spartan refusal to survive defeat, was gone. Over the next few years, the victorious Thebans, led by Epaminondas, dismantled Spartan power in the Peloponnese, reducing Sparta to second-rate status and making themselves the dominant military power in Greece.

It was in the midst of this radical upheaval, then, that Amyntas died, and his son Alexander, about twenty years old at this time, succeeded as Alexander II. He took up the rulership of Macedonia apparently peacefully and without opposition, evidently backed by the powerful barons who had supported his father, including perhaps Derdas and Ptolemy. Like his father, Alexander was obliged to buy off the threat of the Illyrians with tribute payments. Nonetheless, he was full of confidence in himself. The young ruler soon received an appeal from his father’s old allies, the Aleuadae clan of Larissa: there was trouble in Thessaly after the assassination of the great tyrant Jason of Pherae, and the Aleuadae had been driven from their Larissan base and were in danger of losing their dominant position in northern Thessaly. Alexander gladly mobilized a Macedonian force and entered Thessaly, quickly capturing Larissa and surrounding towns. But he did not restore the Aleuadae to power: instead he sought to retain control of northern Thessaly for himself. That proved a grave error of judgment.

Just as many Peloponnesian cities, long oppressed by the Spartans, had appealed to the Thebans, as the new power in Greece, for help, so the Aleuadae and their allies in Thessaly now appealed to Thebes too. And just as Epaminondas led a large Theban force into the Peloponnese to dismantle Spartan power there, so Pelopidas—the other great Theban leader of this time—led a substantial Theban force north, to intervene in Thessaly. Pelopidas’ force was far too strong for Alexander to tangle with: his Macedonian forces were sent back to Macedonia like naughty children, the Aleuadae were restored to power in northern Thessaly, Jason’s successor in Pherae—another Alexander—was confined to his home city, and Thessaly was brought under Theban patronage.

This episode seems to have fatally damaged young Alexander’s standing: when he returned to Macedonia he had to face a rebellion of powerful aristocratic interests led by his own brother-in-law Ptolemy, who rumor had it was conducting an affair with Alexander’s mother (and his own mother-in-law) Eurydice. One party or the other, perhaps in fact Alexander himself, appealed to the Theban Pelopidas to arbitrate, and in 368 Pelopidas entered Macedonia with a substantial entourage and settled the dispute. Alexander was to retain the throne; Ptolemy’s position as powerful baron and adviser to the king was likewise assured; the Macedonians were to be clients of the Thebans; and to assure their future good behavior a number of prominent Macedonians were secured and sent to Thebes as hostages. Among these hostages was Alexander’s youngest full brother, Philip. Aged about fourteen at this time, the young Philip thus came to live in Thebes for three formative years in his mid-teens. In a highly romanticized account, Diodorus has Philip lodge at the house of Epaminondas’ father, there to be educated along with the future star Epaminondas himself. In reality, of course, Epaminondas was at this time already a mature adult, the victor of Leuctra, and was away in the Peloponnesos combating the Spartans. Plutarch tells us that Philip lodged at the house of Pammenes, an associate of Epaminondas and Pelopidas, and a notable leader in his own right.

The point of Diodorus’ fictionalized account of Philip’s time in Thebes is to emphasize the notion that Philip learned about military leadership and governing from and with the great Thebans who dominated Greece in the 360s, and though his details are not true, the general point is universally conceded. Philip certainly absorbed some of the key ideas and strategies of the great Theban leaders during his years as a hostage at Thebes, which were thus a crucial turning point in his life and career.

Epaminondas, Pelopidas, and their associates had begun a revolution in Greek warfare, which Philip was to complete. The standard and dominant style of Greek warfare, that of the heavy infantry hoplite stationed in a phalanx formation several thousand strong, had been developed in the seventh and sixth centuries, and had remained largely unchanged since. The hoplite was a citizen militia soldier, who served in his free time and at his own expense. Most importantly, he provided his own military equipment at his own expense: the standard hoplite panoply included bronze greaves, or shin protectors; a cuirass or corslet to protect the torso; a large bronze helmet covering the entire head, with cut-outs for the eyes and mouth; and a large, heavy, round shield, about one meter in diameter, made of solid wood with extensive bronze reinforcement on the rim and outer face (see ill. 3). This equipment made the hoplite relatively invulnerable to frontal attack, but slow and cumbersome. Several thousand such hoplites drawn up in neat lines and files—usually about eight lines made a standard phalanx—created a fearsome formation. In the narrow plains and valleys of Greece, it was easy to position such a phalanx in a place where its flanks could not be turned: an enemy had to confront it frontally, and try to push it backwards and force it into flight by sheer pressure.

The Spartans had made themselves the undisputed masters of this style of warfare by devoting themselves exclusively to hoplite training and pursuits emphasizing physical fitness: sports and hunting, mostly. The full Spartiate owned an estate worked by helot serfs which provided a living. Freed from such concerns, the Spartiate entered the appalling Spartan training system—the agoge—at the age of seven, and spent his life from then on as a hoplite warrior pure and simple. In essence, the Spartiates were professional soldiers, while the citizen militia warriors of the rest of Greece were amateurs. A Spartan army would normally consist of thousands of allied soldiers, and an elite force of Spartiates generally no more than two or three thousand strong. By the early fourth century, as we have seen, demographic decline had reduced the Spartiate caste to only a little over two thousand, but they were still able to dominate the battlefields of Greece. The elite Spartiate unit would be drawn up, in battle, on the right flank of the army, their allies making up the center and left. As they marched forward to engage, the Spartiates, fitter and better disciplined than their allies, would invariably draw slightly ahead and be the first to engage. Their unique skill and discipline in the art of hoplite infighting and concerted shoving would enable them to drive back the force opposing them on the enemy left very rapidly, whereupon they would turn leftwards and proceed to roll up the rest of the enemy formation from left to right.

In this simple and effective way, the Spartans ruled Greek battlefields for over two hundred years, and the usually so inventive Greeks accepted the traditional way of fighting, accepted the advantage this gave to Spartan collective training and discipline, and let a few thousand Spartiates dominate Greece. The Thebans under Epaminondas and Pelopidas did not end this Spartan dominance by trying to beat the Spartans at their own game, as numerous Greek leaders and armies had failed to do. Epaminondas re-thought the basic strategy and formation of Greek warfare. Normally the best troops in any army were stationed on the right, and the aim when confronted by the Spartans was to use one’s superior right wing to drive away the allies on the Spartans’ left before the Spartiates could win the battle from their own right wing. No one ever succeeded: the Spartans were too good and too quick at their task of driving back their opponents. Epaminondas decided to confront the Spartans head-on, stationing his best troops on his left, opposite the Spartiates, at Leuctra. But he realized that even his best troops could not match the iron discipline and cohesion of the Spartiates, the fruit of their decades of training. He had to find a solution to this, and he found it in a tactical formation of remarkable simplicity. Instead of drawing up his phalanx a standard and uniform eight ranks deep, he thinned out and held back the part of his formation facing Sparta’s allies, and vastly increased the depth of his formation on the left, facing the Spartiates: he knew that if the Spartans themselves were beaten, the Spartan allies would not stay to fight. Forming up his left wing some thirty lines deep, he created a weight of troops that the Spartans simply could not overcome. Though they fought with their usual determination and discipline, the Spartiates were inevitably driven backwards, and Epaminondas used cavalry to harass them from the right as they gave ground. And seeing the Spartiates, to their wonder, being driven back, the rest of the Spartan army gave ground too and turned to flight.

Thus, by applying some careful rational analysis to the process of hoplite fighting, and the reasons for Spartan dominance, Epaminondas and his associates found a simple and elegant solution that ended the myth of Spartan invincibility. During Philip’s stay in Thebes, Epaminondas was mostly away in the Peloponnese, where he dismantled Sparta’s age-old alliance system, known as the Peloponnesian League, whereby the Spartans had successfully kept the Peloponnese subordinated; and he ringed Sparta with two newly created and inherently hostile city-states: Messenia and Megalopolis. Meanwhile Pelopidas was busy during these years campaigning in Thessaly and building Theban dominance in northern Greece. Witnessing this from within Thebes, staying at the house of one of the most important associates of Epaminondas and Pelopidas, Philip too was brought to reflect on the nature of warfare, the weakness of his father and brother as rulers, the inability of Macedonia to compete in hoplite warfare with her southern Greek neighbors, and what might be done to create a military system that would enable the Macedonians to do what the Thebans were doing: break the balance of power in Greece and change it to Macedonia’s advantage. For Philip, when his time came, did not attempt merely to copy what the great Theban leaders had done: he went much further and invented a whole new style of warfare, as we shall see.

In Macedonia, while Philip was at Thebes, things went from bad to worse for Alexander II. Ptolemy had gauged his real weakness, and not long after the agreement brokered by Pelopidas, Alexander was killed—still in the year 368 it seems—while watching a performance of a Macedonian war dance called the telesias. The assassination was evidently carried out on Ptolemy’s orders, and it was he who seized power, ruling nominally as regent for Perdiccas, the next son of Amyntas, and jointly with the queen mother Eurydice. But Ptolemy proved no stronger than Alexander. His power was at once challenged by a rival claimant to the throne, an Argead pretender named Pausanias. It is not clear who this Pausanias was: at a guess perhaps a son of the Pausanias son of Aeropus who had ruled briefly in 393. Such a son would have been in his mid-twenties in 368: an appropriate age to seek power. He apparently enjoyed considerable support in Macedonia, and it was only thanks to a fortuitous intervention by the Athenian commander Iphicrates, old friend and ally (and adopted son) of Amyntas, who happened to be in the northern Aegean with a force on Athenian business, that the challenge of Pausanias was seen off. In 367, however, Pelopidas invaded Macedonia again: he was angered by the upsetting of the settlement he had proposed, and Ptolemy had to buy him off with presents, reassurances, and the handing over of further hostages.

Perceiving Ptolemy’s weakness, Perdiccas began to lay plans to assert himself, take power, and rule in his own right. Born by 384 at the latest, and likely a year or two earlier, he was now at least eighteen years old, and naturally impatient of having a regent ruling for him, particularly perhaps since the regent was co-habiting with his (Perdiccas’) mother. In 366 or early 365 Ptolemy was assassinated and Perdiccas became the ruler of Macedonia as Perdiccas III. Like his older brother Alexander, he felt full confidence in his abilities as ruler and took a number of steps to bolster his position in preparation for a major move to end Macedonia’s humiliating subordination to the Illyrians. Perdiccas re-affirmed Macedonia’s relationship with Thebes, and negotiated the return of his bother Philip after three years. Epaminondas was planning to develop a Theban fleet and challenge the Athenians at sea, and for that he would need Macedonian ship-building timber. Athenian power in the north Aegean, especially her control of the Macedonian ports Pydna and Methone, was irksome, and Perdiccas sought ways to counter this. Athenian pressure on her rebellious former colony Amphipolis provided this: appealed to by the Amphipolitans for help, Perdiccas established a Macedonian garrison in Amphipolis, keeping that crucial city out of Athenian hands and in the Macedonian orbit.

To further shore up his power within Macedonia, Perdiccas established young Philip, in his late teens now, in control of some substantial territory within Macedonia. Unfortunately, our sources do not specify where, nor whether this amounted merely to some estates for Philip to manage, or to governorship of some province or region. But there are some grounds on which to speculate. Philip, notoriously, married many times during his reign, in the usual polygamous manner of Argead rulers. One of his first wives, probably in fact his first, was named Phila and came from the dynastic house of the south-western “canton” in upper Macedonia named Elimea: she was the daughter of Amyntas’ old ally Derdas, and sister of his like-named son, the younger Derdas. It has been speculated that the older Derdas had died, and that in effect, through this marriage, Philip was made by Perdiccas the governor of Elimea, displacing the younger Derdas, who is later met with living in exile. Elimea was an important region, which could be a crucial source of support to an ambitious Macedonian king if it was loyally governed. And its position in the south-west meant it was far enough away from the major barbarian threats to Macedonian security—from the Illyrians, Paeonians, and Thracians in the north—to serve as a secure source of supplies and support to a Macedonian ruler combating those threats.

It is evident that Perdiccas had spent his years as ruler down to 360 building up the Macedonian army. Exactly how he went about this is unclear, though revenues from timber sales to the Thebans and Athenians will likely have helped. What we know is that by 360 he had at his disposal an infantry force many thousands strong, substantially more than four thousand in fact, likely on the order of seven or eight thousand at least. No previous Macedonian ruler is attested to have commanded an infantry force of this size: it was clearly a new development in Macedonia, an infantry force raised by means on which we can only speculate, armed and trained in a manner of which we know nothing. But its purpose at least was clear. Perdiccas ended the tribute payments to the Illyrians, who were still ruled by old Bardylis. When Bardylis responded by leading a major Illyrian invasion of northern Macedonia, Perdiccas marched forth to meet him with his large new infantry army, leaving Philip behind in control of his province—likely, as we have suggested, Elimea.

The outcome of this campaign was disastrous for Perdiccas and Macedonia. In a great battle fought somewhere in north-west Macedonia, likely in Pelagonia, and perhaps not far from Lake Ohrid, Perdiccas and his army were disastrously defeated. The young king Perdiccas III was killed in the fighting, along with, we are told, some four thousand of his men: it is this number of dead that reveals how large Perdiccas’ army had been. Much of the army must certainly have survived: it is rare in warfare for as much as half of an army to die in battle. But the thousands of survivors, leaderless and defeated, could do nothing but flee. Many of them were no doubt captured, but many likely got away, to disperse back to their homes or to whatever other refuge they could find. The Macedonian army effectively ceased to exist, and northwest Macedonia lay wide open to the invading Illyrians, who occupied a large portion of it, the cantons of Pelagonia and Lyncus at the least.

Once again, as so often in these years, Macedonia needed a new ruler. Perdiccas had married some years earlier and left a son named Amyntas, but the boy was not more than two or three years old and could not possibly take up the rulership of Macedonia at this time. That left Perdiccas’ brother Philip, now (late 360) about twenty-four years old; his half-brothers Archelaus, Menelaus, and Arrhidaeus, and two former pretenders still living in exile—Argaeus and Pausanias—to compete for power. It was of course Philip who stepped in, took control of Macedonia, and proceeded over the course of a remarkable twenty-four-year reign to transform Macedonia, and with it the history of the eastern Mediterranean world. Until 360, as we have seen, our knowledge of Macedonia and its history is sparse and sketchy, but the accession to power of Philip as king changed that: for the first time the focus of Greek historians turned northward and centered on Macedonia and a Macedonian ruler. The real history of Macedonia, therefore, begins with the reign of Philip II.