WHEN ALEXANDER DIED HIS UNTIMELY DEATH IN JUNE 323, HE LEFT A massive void behind him. This was not so much because he himself was so great and indispensable, though he had been a remarkable and successful general and ruler. It was the fact that there was no heir capable of taking over his role and ruling the Macedonians and their empire that created an extremely intractable problem for the Macedonian elite. From the moment Alexander took power in 336, Antipater and Parmenio had urged him to marry and start producing children. Had he done so at once, there might have been a ten- or twelve-year-old boy who could be installed as king and groomed, perhaps by a regency council, to take the reins of power within six or eight years. Instead Alexander resisted this advice for ten years, only finally marrying in 327. At the time of his death, his first wife Roxane was six months pregnant with Alexander’s first child; but no one could know whether that pregnancy would be successfully brought to term, and if so whether the baby would be a boy who could potentially become king. Even if both of those outcomes came true, the baby boy could not be expected to take power for about eighteen years. What was to happen in the interim? Thanks to the successful purging of the Argead royal family by Philip and Alexander, to prevent disunity in Macedonia, there were no surviving males of the Argead family other than Alexander’s mentally deficient half-brother Arrhidaeus, who survived only because he was incapable of ruling. Alexander had a sister and two half-sisters—Cleopatra, Cynnane, and Thessalonice—and Cynnane had an adolescent daughter by Alexander’s cousin Amyntas. That was the sum total of the surviving members of the Argead family; and Macedonia, patriarchal to the core, had no tradition of women being able to assume the rulership. It was, consequently, a very worried group of Macedonian leaders who met together in the palace at Babylon after Alexander’s death to discuss the future rule of the empire.

1. THE SETTLEMENT AT BABYLON AND ITS UNRAVELING

One of the problems facing the elite Macedonian officers gathered in conference at Babylon was that not all of the most important Macedonian leaders and power-players were present. Since the death of Parmenio, the two most senior high-level Macedonian commanders were Antipater and Antigonus the One-Eyed, neither of whom was there. Antipater, in his late seventies but still physically strong and active, had been one of Philip’s two most trusted officers throughout his reign, as we have seen, and had served as regent of Macedonia throughout Alexander’s reign. The Macedonian home army, thanks to its thirteen-year service under Antipater, was essentially his army; and he had led it to independent victories, first over Memnon, the rebellious governor of Thrace, but much more importantly over the southern Greek alliance led by Sparta in 330. With the home army behind him, he was not only by far the most respected Macedonian leader, but also the strongest. Antigonus, an almost exact co-eval of Philip, was about sixty years old at the time of Alexander’s death, and had for twelve years been effectively the overseer of Asia Minor west of Cappadocia (that is, the Macedonian-held part of Asia Minor). Formally his satrapy was Phrygia, but he also governed western Pisidia, Lycia, and Pamphylia; he had personally—in defeating the Persian counter-attack in Asia Minor in 331—added Lycaonia by conquest; and the governors of Hellespontine Phrygia, Lydia, and Caria were greatly inferior both in terms of the territory they governed and in status and seniority. As the long-time governor of a huge and strategically important region, with a local security force he had raised himself and led to independent and important victories, he was a leader to be reckoned with.

Just as important as these two, though significantly younger, was Craterus, who after Parmenio’s death had been Alexander’s most trusted general and—along with Hephaestion—in effect his second-in-command. At the time of Alexander’s death, Craterus was in Cilicia in southern Asia Minor in command of a veteran army of ten thousand Macedonian pikemen and fifteen hundred cavalry. He had been instructed in 324 to lead these veterans home to Macedonia, where they were to become the new Macedonian home army and Craterus himself the new regent of Macedonia; Antipater meanwhile was to lead the existing Macedonian home army to Babylon, to join Alexander. Craterus had lingered in Cilicia for some time, for unexplained reasons. He may have been busy in part establishing a royal treasury there for Alexander, at Cyinda. But Antipater had no desire to leave Macedonia and join Alexander: he had in mind the fate of Parmenio, and distrusted Alexander’s intentions. He had sent his son Cassander to Babylon to protest against Alexander’s orders. We may guess that Craterus had little appetite for a confrontation with the great and revered Antipater and his home army, and lingered in Cilicia hoping for further (and different?) orders from Alexander. Had Craterus been at Babylon, he would undoubtedly have taken the lead in the debates among the senior officers there. But even in Cilicia, he was a powerful and widely admired leader—reputedly his popularity among the soldiery was second only to Alexander’s own—and commanded a substantial and highly experienced army. He was the Macedonians’ Macedonian: he stuck to the old Macedonian ways, even to going into battle wearing the distinctive Macedonian kausia on his head. The soldiers adored him, and the sight of his kausia inspired them. He too had to be reckoned with.

The group of officers that met together at Babylon thus did not fully represent the Macedonian high command. The senior officer present was Perdiccas, who had since Craterus’ departure and Hephaestion’s death been acting as Alexander’s second-in-command. After him there was a mix of younger, rising officers, such as Ptolemy, Leonnatus, Seleucus, Peithon son of Crateuas, and Lysimachus; older officers who had never progressed past mid-level commands, such as Aristonous and the phalanx battalion commanders Polyperchon, Attalus, and Meleager; and non-Macedonian Greeks such as Eumenes of Cardia (head of the military secretariat), Nearchus the admiral, and Medeius of Larissa. In the next few weeks and months, it became clear that though Perdiccas saw himself as the future leader of the Macedonian Empire, he was nevertheless rather unsure of himself and his position: he could neither take firm control of events, nor accept a true sharing of power. That was a recipe for conflict. Besides his position as Alexander’s acting chiliarch (second-in-command) during the last year of the young king’s reign, Perdiccas was also strengthened by the fact that one of Alexander’s last actions had been to hand his formal seal of state to Perdiccas, which could be seen as ceding power to him. Yet at the council of leading officers, Perdiccas, instead of using the seal of state as a prop to put forward his claim to power, laid it on the table in a way that seemed to symbolize that power was up for grabs.

There was an immediate split in opinion. Some, notably Aristonous, argued that Perdiccas should hold power as Alexander’s designated successor. Others argued instead for a regency council: Ptolemy was one of the leaders of this group. Both suggestions left open the question of the kingship: traditionally only an Argead descendant of Alexander I could be king. Perdiccas proposed that the question be postponed until Roxane gave birth to her child: if she produced a son, there would be an heir to the throne. Some of the less prominent infantry officers felt themselves overlooked in this discussion. One of them, the phalanx battalion commander Meleager, remembered Alexander’s half-brother Arrhidaeus, and left the council to look for him. Arrhidaeus was about thirty-four or thirty-five years old at this time, and clearly looked like a normal, indeed fairly robust and handsome adult man. That he suffered from some mental deficiency, however, is not in doubt: thrust into prominence by his brother’s death, in the next seven years until his own tragic death he was always controlled by one leading officer or another, never able to act independently and take control of events. Meleager quickly coached Arrhidaeus as to the role he must play, then led him out and introduced him to the Macedonian soldiers who were assembled outside the palace, eagerly awaiting news of the succession, as Philip’s son who deserved to be the new king. Arrhidaeus evidently resembled his great father and looked the part. The soldiers, wanting nothing more than a strong new king to lead them, hailed Arrhidaeus as their ruler, and to symbolize his claim to the throne his name was changed to Philip, like his father. Meleager’s hope clearly was to rule the Macedonian Empire through the good-looking but incapable and pliant Philip Arrhidaeus.

News of this event outside immediately changed the tone of the council meeting. The opposed factions at once united in the face of Meleager’s power grab, and civil strife threatened to break out between the council of high officers, led by Perdiccas and backed by the cavalry and most Macedonian officers, and Meleager, backed by most of the infantry. In the event, cooler heads prevailed. The non-Macedonian Greek Eumenes of Cardia, who had been chief military secretary to Philip and Alexander, and had also functioned as a cavalry commander under the latter, mediated. The outcome was a compromise that recognized everyone’s claims while satisfying no one. Arrhidaeus was recognized as king with the name Philip—Philip III as he is usually known—but Roxane’s child, if it proved to be a boy, as it did, was to be co-king and take over rule of the empire once he achieved adulthood, with the name Alexander like his father—Alexander IV, that is. In the meantime Perdiccas was to actually run the empire on behalf of the kings with the title chiliarch, and Meleager was to be his chief lieutenant. Antipater was continued as viceroy over Macedonia and the European lands of the empire: there was no possibility, as everyone recognized, of deposing him from that position. Craterus was given a vague but honorific title as “protector” (prostates) of the kings, specific powers to be worked out as and when became necessary. Most of the other leading officers were granted governorships of important provinces: Antigonus was confirmed as governor of his super-satrapy in Asia Minor; Ptolemy was granted Egypt; Leonnatus got Hellespontine Phrygia (along the Hellespont and Bosporus); Lysimachus was given Thrace which, thanks to a recent successful rebellion, he would need to conquer himself in order to govern it; and other provinces were similarly parceled out. Eumenes of Cardia, in thanks for his successful mediation, was promised the governorship of Cappadocia, though it was not actually under Macedonian rule as yet. Antigonus and Leonnatus were instructed to oust the surviving Persian governor there, Ariarathes, and install Eumenes as governor. That would be quite a task, as Ariarathes had built up a very strong army over the years, reputedly numbering as much as twenty thousand men.

Perdiccas kept his closest supporters, his brother Alcetas, his brother-in-law Attalus, and Aristonous, around his own person to support him as ruler of the empire. Another key younger leader, Seleucus, was made commander of the Macedonian cavalry, a role that traditionally conferred great authority. One of Perdiccas’ first acts as official chiliarch was to hold a ceremonial rite of purification for the army, after its brief outbreak of strife. At the height of the ceremony, Meleager and a few of his chief supporters were suddenly arrested and brutally put to death, trampled by elephants. Hereby Perdiccas made it clear that despite his initial hesitation, he meant to be ruler of the empire in more than name. None of the other Macedonian leaders seems to have regretted Meleager’s passing: he had made a play for power above his station or abilities. But his fate must surely have made them ponder their own potential vulnerability. Ptolemy hurried to Egypt, and from the moment he took over rule there showed no sign of being ready to accept or obey instructions from the central administration, instead working to make Egypt his own. Antigonus ignored Perdiccas’ orders concerning Cappadocia, clearly displeased that a man so much junior to himself was now in a position to give him orders. Craterus can hardly have been delighted with his vague and undefined role. And Leonnatus harbored ambitions well beyond mere governorship of a relatively minor province. The “settlement” of Babylon, that is to say, in truth settled nothing.

News of Alexander’s death spread quickly and widely, and created two major problems for the Macedonian rulers. Though the subject peoples of Asia, used to submission through two centuries of Persian rule, stayed quiet, and the Persians themselves had been too recently and thoroughly defeated to think of rebelling, the non-Macedonian Greeks in Alexander’s empire did not stay quiet. In southern Greece, the Athenians saw a chance to reassert their independence. Thanks to the disloyalty of Alexander’s treasurer Harpalus, the Athenians possessed a fighting fund of some five thousand talents of Alexander’s money; and thanks to Alexander’s distrust of his regional governors, which had led him to order the disbandment of the mercenary security forces they had recruited to police their provinces, thousands of unemployed mercenaries had gathered to seek employment at the great mercenary fair on Cape Taenarum in the southern Peloponnese. The Athenians mobilized their citizen army and fleet, sent out a call for allies to join them in a war of liberation against the Macedonian oppressor, and despatched their general Leosthenes to Cape Taenarum, amply supplied with funds, to recruit mercenaries. Leosthenes had served as a mercenary commander before and knew these men: he had no difficulty in gathering a large and well-trained army to join the Athenians and greatly strengthen their forces. A number of Greek states responded to their call for allies, most importantly the Aetolians and the Thessalians: Aetolia provided thousands of highly motivated and disciplined light infantry, and the Thessalian cavalry was of as good quality as the Macedonian. Antipater in Macedonia found himself with a formidable war on his hands.

Meanwhile, at the opposite end of the empire in what is today Afghanistan, trouble was brewing too. Alexander had established a dozen or more garrison colonies there, as we have seen, many (most?) of whose inhabitants were Greek mercenary soldiers. However willingly or unwillingly Alexander had settled them in their colonies, at news of Alexander’s death they began sending messages to and fro and before long many thousands of them left their settlements and gathered into a large army, some twenty-five thousand strong. Life in inner Asia did not suit them; their desire was to return home to the Mediterranean and Greece, and they elected leaders and began to march west. This presented a major problem to Perdiccas. If large groups of soldiers were permitted simply to decide for themselves what they would do and where they would go, the authority in the empire of the Macedonian officer elite would be lost. And if the eastern garrisons were permitted to be abandoned, the eastern part of the empire would be lost too. Perdiccas appointed a senior officer named Peithon son of Crateuas to deal with this situation. Peithon was given a large force and instructions to oblige the settlers to return to their garrison colonies. The two armies met in central Iran, and Peithon was victorious. Our sources allege that Peithon had the “rebellious” settlers massacred, but that cannot be true. In fact they were forced back to their colonies. We know this because they and their descendants established a flourishing Greek civilization there that lasted about two hundred years. Though only a handful of references to it survive in our literary sources, it is known to us from the coinages struck by the local rulers there, some of the most beautiful Greek coins ever minted (see ill. 1 for an example); and from the French excavation, in the 1970s, of one of their cities at a place in Afghanistan called Ai Khanum.

The crisis in the east was thus settled fairly quickly, and with great credit to Peithon and his boss Perdiccas; the situation in Greece proved much more tricky. When Antipater marched south with the home army to deal with the uprising, he was met in north central Greece by an Athenian and mercenary army commanded by Leosthenes, and defeated. Antipater barely managed to disengage his defeated army still intact, and took refuge behind the walls of the nearby city of Lamia, where he was obliged to stand a siege. As a consequence, this conflict is known to modern historians as the Lamian War. Antipater sent desperate messages to Asia Minor, to the Macedonian leaders there, calling for help. Two leaders heeded the call: Leonnatus in Hellespontine Phrygia ignored his orders from Perdiccas to conquer Cappadocia for Eumenes, and instead took the forces Perdiccas had given him for this purpose across the Hellespont into Europe and over into Macedonia. There he recruited additional troops and prepared to go to the rescue of Antipater. In addition Leonnatus established contact with Alexander’s full sister Cleopatra, widow of Alexander the Molossian. He proposed to marry her: he came of a princely house himself, and thought that with Cleopatra by his side he could make a play for the Macedonian throne. It all came to nothing when he moved south into Thessaly and was met by the Athenian army and defeated. Leonnatus died of his wounds, and Antipater—relieved from his siege at Lamia by Leonnatus’ entry into the fight—managed to collect the remnants of Leonnatus’ defeated force and retreat with them and his own army back to the safety of Macedonia.

The other Macedonian leader who heeded Antipater’s call for help was Craterus, who was still lingering in Cilicia. He did not move at once because, concerned about Athenian naval power, he stayed to collect a great fleet from Phoenicia, Cyprus, and Cilicia, which he placed under the command of his officer Cleitus the White. Cleitus defeated the Athenian fleet in two great sea battles, at the island of Amorgos and in the Hellespont, ending Athenian naval power once and for all. Craterus was able to ferry his veteran army across to Macedonia safely, and there join up with Antipater. The joint armies of Antipater and Craterus, along with the troops Leonnatus had gathered, represented a great army indeed, and the two leaders prepared for a show-down battle with the Athenians and their allies in the spring of the following year, 322. The battle was fought at Crannon in Thessaly and, thanks to outstanding service from the Thessalian cavalry and the rest of the southern army, was fought to a draw. But a draw was as good as a victory to Antipater and Craterus. Immediately after the battle, allied contingents in the southern Greek army began to peel away and head for home, or even sue for peace on favorable terms. The Athenian coalition melted away, and the Macedonian leaders were able to advance southwards, pacifying the Greek states as they went, until they finally reached Athens in October 322. The Athenian democracy was ended and a pro-Macedonian oligarchic regime installed in its place.

There were still mopping-up operations to be conducted, particularly against the Aetolians, but Antipater and Craterus were victorious, and had established an excellent partnership with each other. This was now cemented by a marriage alliance: Craterus married Antipater’s oldest daughter Phila. The two then considered their relations with Perdiccas. The latter had successes of his own to his name: frustrated at the failure of Antigonus and Leonnatus to obey his orders to conquer Cappadocia, he had come to Asia Minor himself, bringing the royal army. He invaded Cappadocia, defeated the forces of Ariarathes, and installed Eumenes as the new governor of the region, as he had planned. He then moved south and invaded eastern Pisidia, which like Cappadocia had not yet come under Macedonian rule. There too he was victorious, and the fall of 322 found him established in winter quarters in Pisidia with a greatly enhanced reputation. Antipater sent representatives to Perdiccas proposing a marriage alliance: Perdiccas would marry a second daughter of Antipater, named Nicaea, and thereby become the brother-in-law of Craterus at the same time. Thus the three great leaders, related by ties of marriage, could in future rule the Macedonian Empire on behalf of the kings as a triumvirate. That was clearly an excellent idea, promising stability to the empire, as no Macedonian leader could hope to stand up to these three and their forces, and Perdiccas promptly agreed … only to suffer almost immediately a case of buyer’s remorse. For at that very time there arrived letters from Olympias and Cleopatra, Alexander’s mother and sister, proposing that Perdiccas marry Cleopatra instead. Olympias loathed Antipater. Marriage to Cleopatra would mean a decisive break between Perdiccas and Antipater; but it offered Perdiccas the prospect, as uncle-by-marriage of the young king Alexander IV, of ruling the Macedonian Empire on his own, with Cleopatra and Olympias by his side, in the name of his young nephew.

Here Perdiccas’ basic indecisiveness reared its head again. His good friend Eumenes, who was also a long-time friend of Olympias, urged Perdiccas to accept Cleopatra’s offer and marry her. But Perdiccas’ brother Alcetas, more cautious by nature, urged him to stand true to his agreement with Antipater and Craterus, and marry Nicaea. Unable to quite decide, Perdiccas gave encouragement to both ladies, with the result that both arrived in Asia Minor early in 321 expecting marriage. To complicate matters further, two more royal Macedonian ladies arrived at Ephesus on the coast of Asia Minor around the same time, also in pursuit of a marriage: Philip’s oldest daughter Cynnane brought her young daughter Adea with the project of marrying her to the senior king Philip Arrhidaeus, no doubt expecting that as wife of the pliant Philip Adea could take control and rule in his name. Perdiccas sent his brother Alcetas with some troops to arrest these princesses, probably with the idea of sending them back to Macedonia. But Cynnane resisted and was killed in the violence that ensued. Alcetas’ own Macedonian soldiers then rebelled against him, horrified that a daughter of the great Philip had been killed. In order to quiet the uprising, Alcetas and Perdiccas were forced to agree to Adea marrying Philip: like her new husband, Adea then changed her name and took on the royal name Eurydice instead. For the moment Perdiccas was able to keep young Adea Eurydice under his control, but the situation was becoming fraught. Still undecided about his own future, Perdiccas established Cleopatra comfortably at Sardis and sent his friend Eumenes to keep her sweet, while himself receiving Nicaea and formally marrying her. It was clear to his entourage, however, that Cleopatra, and the prospects she opened up for him, was the one he really wanted. Things were heading towards a crisis.

The crisis was precipitated by Antigonus and Ptolemy. Perdiccas was still angry at Antigonus’ refusal to invade Cappadocia, and summoned him to explain himself. Antigonus had no intention of justifying himself to a more junior officer, and no doubt had Meleager’s fate in mind. He collected his relatives, friends, and belongings, and fled to Macedonia on several Athenian ships, taking refuge with his good old friend Antipater. There he complained vociferously about Perdiccas’ actions; and he kept tabs via his friend Menander, the governor of Lydia, on Perdiccas’ relationship with Cleopatra, on which he reported to Antipater and Craterus. Ptolemy was pursuing an independent policy aimed at making Egypt his own realm. To do this, he played up his own connection to Alexander to portray himself as Alexander’s legitimate heir in Egypt: he built up Alexandria, the city which Alexander had formally founded but not waited to build. And when Alexander’s funeral cortege, with a lavish coffin and wagon it had taken more than a year to build, passed through Syria on its way to Macedonia, Ptolemy intercepted it with troops and carried it off to Egypt where Alexander was first buried in the old capital of Memphis but eventually moved to a magnificent purpose-built tomb in Alexandria itself. This was a direct affront to Perdiccas, who had intended to bring Alexander “home” to Macedonia for burial at the ancestral Argead tomb complex in Aegae, the old Macedonian capital. Perdiccas reacted by finally being decisive: he repudiated Nicaea and sent Eumenes to Cleopatra again to announce his (Perdiccas’) intention to marry her. That meant war with Antipater, Craterus, Antigonus, and Ptolemy. The “settlement” of Babylon was broken.

The first War of the Diadochi (Successors of Alexander) did not last long. It was fought on three fronts, with different outcomes, though the overall winners were undoubtedly Antipater and his allies Antigonus and Ptolemy. Antipater and Craterus gathered their forces to march to and cross the Hellespont into Asia Minor to confront Perdiccas. Antigonus took a detachment of ships and sailed to the coast of Ionia, where he joined up with his friend Menander. He learned there of Perdiccas’ definitive decision to marry Cleopatra, and sent word to Antipater to hurry his invasion into Asia Minor. Ptolemy built up the defenses of Egypt along the easternmost Pelusiac branch of the Nile delta, and awaited events. With his usual indecision, Perdiccas summoned a council of his closest advisers to decide what to do: should he march south to punish Ptolemy, or should he march to the Hellespont to confront Antipater and Craterus? Rather typically, he selected the apparently easy option: he would deal with Ptolemy. He left a large force in Asia Minor under his friend Eumenes with orders to guard the Hellespont and not permit Antipater to cross; Alcetas, with another force, was instructed to co-operate with Eumenes, as was another Macedonian officer named Neoptolemus. Aristonous, finally, was sent with a detachment to take control of Cyprus, to deny its resources to his enemies and have it serve instead as an advance staging post for his own operations. And so Perdiccas marched through Syria and Palestine, with a fleet commanded by his brother-in-law Attalus accompanying him.

Perdiccas’ confrontation with Ptolemy’s forces in Egypt was disastrous. Several attempts to force a crossing of the Nile were repelled with heavy losses, and the soldiers were particularly demoralized when Nile crocodiles collected in large numbers to feast on the bodies of the dead. When it became clear that Perdiccas did not know what to do next, a group of senior officers led by Peithon, Seleucus, and Antigenes, the commander of the Silver Shields (formerly Philip’s pezetairoi and then Alexander’s hypaspistai), confronted Perdiccas in his tent at night and assassinated him. When word of this reached him, Ptolemy crossed over the river and addressed the men of the royal army at a meeting. He expressed how sorry he was to have been forced into conflict with them and how much he regretted their losses; and he pledged to provide them with supplies and other aid. The men cheered him, and called for him to take up the regency of the kings now that Perdiccas was dead. Ptolemy, foreseeing conflict with Antipater and Antigonus if he took that post, declined. Two other senior officers—Peithon son of Crateuas and Arrhidaeus (not king Philip III Arrhidaeus but another Macedonian officer of that name)—were nominated to the post instead, for the time being. The remaining adherents of Perdiccas in the camp were seized and killed, including his unfortunate sister, and more than thirty others were condemned to death in absentia, including the fleet commander Attalus, Perdiccas’ brother Alcetas, and Eumenes. Then the army turned and marched back through Palestine towards Syria for a rendezvous with Antipater.

Meanwhile, Antipater and Craterus had crossed the Hellespont unopposed: the forces that were supposed to prevent the crossing were in conflict with each other. Alcetas, angry at being subordinated to the non-Macedonian Eumenes, refused to co-operate with him and took his forces off to Pisidia in southern Asia Minor. Neoptolemus too resented having been placed under Eumenes and was in contact with Craterus, intending to switch sides. Far from opposing Antipater and Craterus at the Hellespont, therefore, Eumenes was forced to fight against his own supposed ally Neoptolemus, soundly defeating him and taking over his army. When Neoptolemus rode into Antipater’s camp with only a few dozen cavalry as escort to announce his defeat, a council of war was held. Antipater and Craterus decided to split their forces. Craterus would take his Macedonian veterans and, guided by Neoptolemus, would confront Eumenes and assure control over Asia Minor for his side. Antipater, meanwhile, would march south with his troops as fast as possible to assist Ptolemy; and Antigonus with his ships and a small force would proceed to Cyprus to seize that island.

Craterus’ confrontation with Eumenes did not work out as planned. During the previous two years Eumenes had raised and trained a large force of Cappadocian cavalry, with which he confronted Craterus’ cavalry on one wing of the battle with orders to charge hell for leather and not give Craterus the chance to choose his own moment to engage. Eumenes distrusted the loyalty of the Macedonian element among his infantry, if they knew that they were going up against the beloved Craterus. He assured them that their opponent was only Neoptolemus with some new forces, and held his infantry back, determined to try to win with his cavalry. On one wing, Eumenes led part of his cavalry in a charge against enemy cavalry commanded by Neoptolemus. The two commanders met in person, and in a vicious fight Eumenes managed to kill Neoptolemus with his own hands, and emerge victor. On the other wing, Eumenes’ cavalry charged Craterus and his Macedonian cavalry and, in the midst of the fighting, Craterus’ horse stumbled and he had the misfortune to be thrown and then trampled by the Cappadocian horses. When Eumenes found him after the battle, he was dying: an ignominious death for the most highly regarded of Alexander’s officers. Craterus’ defeated forces offered to surrender to Eumenes and camped where they were for the time being. In the middle of the night, however, they decamped and marched away at full speed to rejoin Antipater. Antigonus, meanwhile, successfully took control of Cyprus, driving out Aristonous and his force, and then moved on to rejoin Antipater in northern Syria. As a result, Antipater with his own army and Craterus’ army, and joined by Antigonus’ force too, arrived at a Persian resort spot in northern Syria named Triparadeisus (literally “three gardens”) where the royal army under Peithon and Arrhidaeus was awaiting him. It was time for a new council of Macedonian leaders, and a new “settlement.”

2. THE SETTLEMENT OF TRIPARADEISUS AND ITS UNRAVELING

With Perdiccas and Craterus, the two younger generals most trusted by Alexander, both dead, a completely new arrangement of power in the Macedonian Empire was called for. There could be only one choice for the regency: Antipater. As by far the most senior commander, right-hand man of Philip, viceroy of Macedonia throughout Alexander’s reign, revered by everyone, he had no rival. A brief upset was caused by the young Eurydice asserting her right to rule in her husband Philip’s name: many of the soldiers admired her spirit and her royal birth. When Antipater attempted to assert control a riot threatened, but order was quickly restored by the intervention of Antigonus and Seleucus, both huge and physically imposing men. Antigonus had a squadron of cavalry escort the aged Antipater to safety, and a council of all the main Macedonian leaders was then summoned in Antipater’s camp. Eurydice was made to understand that as a woman she must stay quiet and obey; Antipater was formally acknowledged as the regent of the kings and so ruler of the empire; and a new division of powers was put into effect.

A simplifying factor was that Egypt no longer had to be considered: it belonged to Ptolemy. He had governed it successfully for several years now, had built up his own army there, and had defended it effectively from Perdiccas’ attack. There was no question of trying to interfere with him. One thing Antipater also made clear from the beginning was that he had no intention of staying in Asia. He would be returning to Macedonia as soon as possible, and would oversee the empire from there. This meant that he would need a strong leader to act as his lieutenant in Asia, overseeing the governors and the running of imperial affairs there. There could be little doubt on whom the choice would fall for this role: Antigonus was the next most senior leader, he had independent successes to his name, he was a close friend of Antipater, and he would certainly not tolerate anyone being placed above him. He was, therefore, appointed general with oversight of the Asian provinces, and also given the specific task of finishing the war against Perdiccas’ surviving supporters, Alcetas and Eumenes, who could not be forgiven for the death of Craterus. To fulfill this task and these responsibilities, Antigonus was given command of the royal army most recently led by Perdiccas, and to keep an eye on him Antipater appointed his own son Cassander to be Antigonus’ second-in-command. Along with the royal army, Antigonus was also to have personal oversight of the kings, which meant that he was effectively designated as the aged Antipater’s successor in the regency: for so long as Antigonus had the kings, it was obvious no one but he could take the regency when Antipater died.

Thought was then given to governorships of the provinces. Many existing governors were simply confirmed, but there were a number of officers who needed to be rewarded, and a number of close associates of Perdiccas who needed to be deposed. The two temporary regents, Peithon and Arrhidaeus, were rewarded with governorships over Media and Hellespontine Phrygia respectively. Peithon already had experience in the east, in his victorious campaign against the “rebellious” Greek colonists, and from the powerful satrapy of Media could exercise oversight of the further east; Hellespontine Phrygia had no governor since the death of Leonnatus. The other two assassins of Perdiccas, Seleucus and Antigenes, were granted the governorships of Babylonia and Susiane. Antigenes, however, remained commander of the Silver Shields for the time being, with a special task of convoying treasure to be deposited at Cyinda in Cilicia, meanwhile ruling Susiane through a deputy. With this business settled, Antipater set off with his army to return to Macedonia, and Antigonus with the royal army marched with him, headed for Asia Minor and the war against Eumenes and Alcetas. Along the way, friction arose between Antigonus and Cassander, leading to a revision of some key arrangements. Cassander was clearly not suited to be Antigonus’ second-in-command, and he persuaded his father that it would be unwise to leave the kings under Antigonus’ charge. Antipater therefore took the kings and a large portion of the royal army, leaving Antigonus eight thousand of his own younger Macedonian soldiers instead. With the kings and Cassander now in his entourage, Antipater crossed over to Europe and returned to Macedonia. Antigonus with his smaller but more manageable and reliable army gave thought to fighting Eumenes.

Antigonus was a huge man with a booming voice, a scarred face where he had lost one eye at the siege of Perinthus in 340, and an abundance of energy. He had had to wait a long time to play a leading role: born about 383/2, he was around sixty-three years old when appointed general over Asia in 320. He was determined to make the most of this delayed opportunity. He spent the fall and winter of 320 to 319 preparing his forces and laying his plans, and made his move in spring of 319, advancing to meet Eumenes with an army about fifteen thousand strong. Eumenes was in his province Cappadocia, where he had collected an army well over twenty thousand strong, based on the troops originally granted him by Perdiccas but with additions from the defeated forces of Neoptolemus and Craterus. His main strength was in cavalry: the excellent Cappadocian cavalry he had himself recruited and trained. The two armies drew together in southern Cappadocia, at a place called Orcynia, where Eumenes was completely out-generaled by Antigonus. By a clever stratagem Antigonus persuaded his opponents that substantial reinforcements had reached him just before the battle, demoralizing them by the belief that far from outnumbering Antigonus’ army they were now the smaller of the forces. And Antigonus also succeeded in establishing contact with one of Eumenes’ key cavalry commanders, persuading him to switch sides with his squadrons during the battle. The result was a devastating defeat for Eumenes, from which he escaped with a few hundred men to take refuge at a small fortress named Nora, where Antigonus besieged him. Eumenes was a quick study, however, and learned from his defeat: he was to prove a much tougher opponent in the next few years.

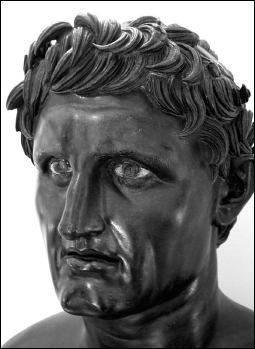

16. Macedonian ruler (probably Antigonus the One-Eyed) from villa of P. Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale, now in Metropolitan Museum, New York

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

Antigonus left a small force to besiege Eumenes in Nora, and with the bulk of his army, now supplemented by most of Eumenes’ defeated army, carried out an astonishing forced march across southern Asia Minor from Cappadocia to southern Pisidia, where Alcetas and his army were encamped near the city of Cretopolis. Alcetas and his men were heedless of any danger, secure in the belief that Antigonus was hundreds of miles away in Cappadocia. The first they knew of Antigonus’ army being present and about to attack was when they heard the trumpeting of Antigonus’ advancing elephants. With Alcetas’ army taken completely by surprise, the engagement was not so much a battle as a rout. Most of Alcetas’ army and officers surrendered to Antigonus; Alcetas himself fled to the nearby friendly city of Termessus, where he was subsequently killed by citizens seeking to gratify Antigonus. In one swift campaign taking only a couple of months and characterized by boldness, speed of movement, and brilliant improvisation, Antigonus had defeated and incorporated into his own force two rival armies, and ended the war against Perdiccas’ supporters. As he marched back towards Cappadocia to finish with Eumenes in late summer of 319, Antigonus received momentous news: the aged Antipater had succumbed to illness, and on his deathbed had nominated the former phalanx battalion commander Polyperchon to succeed him as regent. Antigonus had no intention of obeying the rather mediocre Polyperchon, however; and neither did a number of other Macedonian leaders. Already the “settlement” of Triparadeisus had began to unravel, beginning the second War of the Diadochi.

This renewed war was fought essentially on two fronts. Though the coalition opposing Polyperchon included Ptolemy and Lysimachus in its number, they were in fact fully engaged in securing their own realms of Egypt and surrounding territories, and Thrace, respectively. The fighting occurred in the east, where Antigonus with various allies fought out an extended and remarkable duel with Eumenes and a fractious coalition of allies; and in the west, in Greece and Macedonia, where Antigonus’ ally Cassander challenged Polyperchon. Antipater’s choice of Polyperchon as regent has always been something of a mystery: in many years of service under Philip and Alexander Polyperchon had never risen above the rank of battalion commander, nor apparently shown much ambition to do so. Antipater, when leaving to attack Perdiccas in Asia, had appointed Polyperchon to oversee Macedonia and Greece, and Polyperchon had done so capably. But it may well be that it was the man’s very mediocrity that appealed to Antipater: he wanted, we may suppose, a regent who would have no ambition to supplant the legitimate kings, who would hand over quietly to Alexander IV when the time came. But this choice infuriated Cassander, who had naturally expected to succeed his father as regent; and left men like Antigonus and Ptolemy deeply unimpressed. Cassander promptly fled from Macedonia to start building up forces of his own for a rebellion, and Antigonus and Ptolemy simply ignored Polyperchon as a man of little account.

Sensing his weakness, Polyperchon attempted to shore it up by three main expedients. He wrote to Alexander’s mother Olympias inviting her to return to Macedonia from her self-imposed exile in Epirus, to take up oversight of her grandson Alexander IV and his education. He announced to the cities of southern Greece that the oligarchies established by Antipater would be abolished, and that the cities would be free to create their own favored governing systems: in effect Polyperchon feared that the oligarchs would be more loyal to Antipater’s son Cassander than to the new regent, and rightly so. And Polyperchon sent letters to Eumenes in Asia, offering him appointment as royal general over Asia, authorizing him to draw upon the royal treasuries in Asia for any necessary funds, and instructing all loyal officers and governors in Asia to obey and co-operate with Eumenes. The effectiveness of these moves varied. Olympias stayed where she was for the time being, lacking confidence in Polyperchon, but she did write to Eumenes urging him to accept Polyperchon’s offer and asking for advice. The oligarchic regimes in southern Greece did not give up power: instead they predictably turned to Cassander for help, and bolstered his position as rival to Polyperchon. The latter would have to intervene militarily in southern Greece to achieve real change. The letters to Eumenes had the greatest effect, tying up Antigonus with a major war in Asia and preventing him from intervening against Polyperchon directly. For Eumenes was no longer besieged in the small fortress of Nora in Cappadocia.

Late in 319 Antigonus had learned of Antipater’s death from Eumenes’ close friend and (probable) relative Hieronymus of Cardia, who was later to become the greatest historian of this period. Taking stock of his situation, Antigonus had decided that he would take no more orders from the central government, despising Polyperchon the new regent, but would operate strictly on his own behalf. He calculated that Eumenes, an old friend from the days they had served Philip together, could be a very useful ally, and sent Hieronymus to him with proposals offering Eumenes a high position as one of his chief officers and advisers. Eumenes pretended to agree and was released from his siege; but instead of joining Antigonus he accepted the position of overseer of Asia offered by Polyperchon, which is to say he became Antigonus’ chief rival. He made his way to the royal treasury at Cyinda in Cilicia, where there were ample funds for his purposes guarded by the famous three thousand strong unit called the Silver Shields. As already discussed, these men were the former guard unit of Philip (when they had been known as pezetairoi) and Alexander (when they had been known as hypaspistai). They were the most experienced and feared military unit in the Macedonian Empire, indeed one of the supreme infantry units in military history, comparable in their discipline, ferocity, and elite status to Caesar’s tenth legion or Napoleon’s “Old Guard.” The Silver Shields, along with a younger unit of three thousand men known as the hypaspistai who were being trained as their replacements, accepted the orders in Eumenes’ letters from Polyperchon and Olympias, and took service under him. With their help and the funds from Cyinda, Eumenes was in a strong position to make trouble.

Before Antigonus could try to deal with Eumenes, however, he had another troublesome situation to deal with: Craterus’ former admiral Cleitus the White appeared in the Propontis (Sea of Marmara) with a great fleet as Polyperchon’s ally. Affairs in Greece had not been going well for Polyperchon. To counter his rival Cassander’s influence with the oligarchies and garrisons installed in many southern Greek cities by Antipater, Polyperchon had declared all Greek cities free to establish whatever governing system they desired (which in effect meant democracies), but it would take military force to make that declaration effective. Meanwhile, Cassander controlled most of southern Greece through various allies, and also received allied troops from Antigonus and Ptolemy. Since he had control of the Piraeus, the great harbor of Athens, through his friend Nicanor, the commander of the Macedonian garrison there, he was able to mobilize the remnants of the Athenian fleet along with ships gathered from elsewhere in southern Greece to seek control of the sea. Nicanor led this fleet to the Hellespont and Propontis to join up with a flotilla of ships gathered there on Antigonus’ behalf, and Polyperchon had persuaded Cleitus to side with him against Cassander and Antigonus, and go in pursuit of Nicanor’s fleet. Antigonus hastened to the Propontis to take command of this fleet, but arrived too late. In summer 318 the two fleets met in battle near the entrance to the Bosporus, and Cleitus won a clear victory. The bulk of Nicanor’s fleet escaped from the battle to port on the Asian shore intact, but greatly dispirited; while Cleitus and his ships encamped on the European shore to celebrate their victory. Antigonus arrived the night after the battle, immediately took command, and set about redressing the situation.

Realizing that the crews on the ships were demoralized by their defeat, Antigonus had the fleet transport most of his army across the Bosporus to the European shore, while posting detachments of his soldiers on the ships to ensure that they would obey orders and fight. The fleet rowed quietly to lie in wait outside Cleitus’ camp, while Antigonus marched the bulk of his army along the shore to spring a surprise night attack. Cleitus’ men were indeed taken completely by surprise, sleeping off their victory celebration; and as the sounds of fighting rose in the night air, Antigonus’ ships attacked from the sea. Just hours after its seemingly decisive victory, Cleitus’ fleet was captured by Antigonus with scarcely a struggle. Cleitus himself managed to escape with a few ships, but was forced to land and there captured and killed by soldiers allied to Antigonus. Nicanor sailed back to Athens victorious, the prows of his ships decorated with victory wreaths, to boost Cassander’s already successful operations there. Cassander, in fact, was proving to be more than a match for Polyperchon, who turned out to be the classic officer promoted beyond his abilities. His attempts to win control of Greek cities failed, and an attempted siege of Megalopolis proved disastrous. In 317 Polyperchon was forced to retreat to Macedonia with nothing accomplished, leaving Cassander to consolidate his control over southern Greece and lay plans for invading Macedonia.

Meanwhile, his victory near the Bosporos freed Antigonus to deal with Eumenes. He sent messengers to Cyinda to try to detach the Silver Shields from their allegiance to Eumenes, and divided his forces. He had about sixty thousand soldiers available at this point, and selected the twenty thousand fittest to accompany him to confront Eumenes, leaving the remainder under loyal officers to secure full control of Asia Minor. The messengers he had sent to the Silver Shields, as well as others sent by Ptolemy, had failed to detach them from their loyalty to Eumenes. But the latter did face a problem of disloyalty: it came from the senior Macedonian officers of his troops, who resented being subordinated to a non-Macedonian Greek. This was especially true of Antigenes and Teutamus, the commanders of the Silver Shields and the Hypaspists, respectively. To overcome this, Eumenes pretended to have had a dream in which Alexander himself had appeared to him and instructed him to hold collegial meetings in a leadership conference to be held in his (Alexander’s) own tent. Setting up a tent formerly used by Alexander, with suitable furnishings, and sacrificing ritually to Alexander, Eumenes presided over councils of the leading officers in Alexander’s name, and found it easy enough to persuade them to see things his way. Learning that Antigonus was approaching with a numerically superior force, Eumenes did not wait for a showdown: he moved his army south into north Syria and Phoenicia, and there learned news from the east that greatly encouraged him.

While Cassander and Polyperchon were fighting it out in Europe, and Eumenes and Antigonus were confronting each other in western Asia, trouble had arisen in the eastern or “upper” satrapies (provinces) of the empire too. The strongest governor in the east was Peithon, son of Crateuas, who had defeated the rebellious Greek colonists in the east on behalf of Perdiccas in 322. As governor of Media now, he sought to assert his domination over all of the eastern satraps. They resisted this, and wisely banded their forces together, led by the governor of Persia, Peucestas. A showdown ensued in which Peucestas and his colleagues defeated Peithon and his army. Forced into flight, Peithon with the remnants of his forces took refuge with Seleucus, the governor of Babylonia and an old friend of Peithon. While they were planning together how to get the best of the “upper” satraps, Eumenes appeared leading his small but potent army eastwards through Mesopotamia. Eumenes had calculated that by combining either or both of the two eastern armies with his own forces, he would be strong enough to confront Antigonus with a good prospect of success. Attempts to negotiate with Seleucus and Peithon failed, however: they were both, as we have seen, deeply implicated in the assassination of Eumenes’ good friend and patron the former regent Perdiccas, and they neither trusted nor liked Eumenes. On the other hand, envoys sent to Peucestas and the “upper” satraps received an encouraging welcome: they were seeking support against a renewed attack by Peithon and his ally Seleucus, and were very willing to combine with Eumenes to that end. So Eumenes hurried eastwards to link up with the army of the eastern satraps near Susa. Combining his forces with theirs, he now commanded an army of at least forty-five thousand, including strong cavalry forces and war elephants in addition to his own incomparable Silver Shields.

When Antigonus appeared in Mesopotamia pursuing Eumenes, he was met by messengers of Seleucus and Peithon warning him of Eumenes’ new strength. Realizing that his army of about twenty thousand was no longer adequate, Antigonus encamped in Mesopotamia for the winter while sending for additional forces to come to join him, and also sealing an alliance with Peithon and Seleucus. At the beginning of 316 he crossed the Tigris and marched for Iran with an army in excess of fifty thousand men, including strong and excellent cavalry forces in addition to nearly twenty thousand Macedonian or Macedonian-trained and equipped infantrymen. This led to a remarkable campaign lasting a little over a year between two very evenly matched armies of the same type and composition, and two brilliant and inventive generals, whose skills and efforts to outmaneuver each other remind one of a match between chess grandmasters.

Initially, Eumenes faced difficulties asserting control over the ambitious Macedonian generals and governors commanding the various units of his disparate army. He used a variety of ploys to establish and maintain his leadership. The Alexander command tent made its reappearance, for example; the letters signed by the regent and the kings gave Eumenes access to the royal treasury at Susa, enabling him to pay his troops well and distribute gifts; on the other hand, he borrowed money from some of the governors against a promise of handsome repayment terms once he was victorious; and on one occasion he forged letters from Polyperchon and Olympias reporting that Cassander was defeated and dead, and a large relief army commanded by Polyperchon himself on its way to aid him. By these various stratagems and others, Eumenes did retain control over his army, helped greatly by the fact that the soldiers trusted him more than any other general. He decided, however, that he needed time to prepare his army before facing Antigonus, so leaving Susa and its treasury strongly fortified and guarded by a loyal officer, he marched south into Persia. Arriving at Susa to find Eumenes gone and the city’s gates closed to him, Antigonus left Seleucus with several thousand men to besiege the place, and moved south in pursuit of Eumenes’ army.

Eumenes had had two years now to reflect on how he had been outwitted and outmaneuvered by Antigonus in the campaign and battle of Orcynia, and proceeded to show that he had learned from his defeat. Arriving at a deep and swift-flowing river in northern Persia called the Copratas, Antigonus found only enough boats to ferry his men across a few thousand at a time. That would be very risky, but since the opposite bank seemed deserted, he took the risk, ordering the first contingent to start preparing a fortified camp while the rest crossed. However, Eumenes had a large force concealed nearby, which emerged when only the first group of Antigonus’ troops had crossed and caught them isolated on the south bank, cut off by the deep river from the bulk of Antigonus’ army. More than four thousand of Antigonus’ soldiers were killed or captured, a severe setback which demoralized Antigonus’ troops, who had been forced to watch helplessly the fate of their comrades. It was Antigonus’ turn to retreat, to find time and space in which to repair his army’s morale. He decided to march north into Media, Peithon’s satrapy, to rest and recuperate his army, which suffered from the summer heat in Persia. In Media he found funds in the royal treasury at Ecbatana, and was able to supply his men with everything they needed in abundance, including fresh horses. The move was risky in that it opened to Eumenes the possibility of marching west to attack Antigonus’ lands in Syria and Asia Minor, but Antigonus rightly calculated that the eastern governors would refuse to allow their troops to be marched so far from their provinces while Antigonus and his army were in the east. So Eumenes in fact marched deeper into Persia, and the two forces spent the hottest months of summer 316 resting and preparing for the coming showdown, one in Media and the other in Persia.

In late summer it was Antigonus who made the first move, marching south with his army into a region of central Iran named Paraetacene. Informed of Antigonus’ move, Eumenes marched north to meet him. When the two armies came together, they drew up in strong positions about half a mile apart on either side of a steep ravine, each challenging the other to try an attack at a severe disadvantage. Neither was inclined to take the risk, and after several days of posturing, supplies in the area ran short and Antigonus decided to march away by night into a richly stocked neighboring area named Gabiene. However, Eumenes learned of this plan from deserters, and sent apparent deserters of his own into Antigonus’ camp to warn of an intended night attack by Eumenes. While Antigonus therefore kept his army under arms through the night awaiting attack, it was Eumenes who stole away in the night with his army towards Gabiene. Learning in the morning how he had been tricked, Antigonus set out in pursuit of Eumenes with his best cavalry, ordering his infantry to rest awhile and then follow at the best speed it could manage. Eumenes had just emerged from a range of hills into a broad flat plain when Antigonus’ cavalry appeared on the crest of the hills behind him. Fearing that Antigonus’ entire army was there, Eumenes had to stop his march and draw up his army for battle. Meanwhile Antigonus simply kept his cavalry in plain view to hold Eumenes in place, and waited for the rest of his army to catch up. When it did, he arranged them in battle formation and marched down into the open plain to confront Eumenes. Diodorus comments (19.27) on the awe-inspiring sight Antigonus’ army made as it marched down from the foothills into the plain, making it clear that he was drawing on an eye-witness report: undoubtedly that of Eumenes’ officer, the historian Hieronymus of Cardia.

The two armies were very evenly matched: each was rather more than forty-one thousand men strong; each had as its heart units of Macedonian or Macedonian-style heavy infantry twenty thousand or more strong, along with mercenaries and light infantry. Antigonus had the advantage in cavalry, well over ten thousand to a little more than six thousand; but against this Eumenes had the matchless Silver Shields as the core of his infantry. The battle was fought very much in the style of Philip and Alexander: each general stationed his best cavalry on his right under his own command, withheld his left, and ordered his infantry to advance steadily to try to drive back the opposition. The aim was to wait for a suitable opportunity for a decisive cavalry charge on the right. In the event, the fight did not work out quite as planned, however. Peithon, stationed in command of Antigonus’ left with a large force of light cavalry, decided to try to win the battle himself and charged Eumenes’ right instead of holding back. He was defeated and driven back to take refuge among the foothills behind Antigonus’ army. Meanwhile, the Silver Shields took the initiative and charged at a swift pace into Antigonus’ infantry, who could not withstand their ferocious impetus. Antigonus’ phalanx was driven back, fighting hard, to join Peithon. The battle threatened to become a disaster for Antigonus, but with typical coolness and decision he refused to retreat to join the rest of his army but led a cavalry charge on his right which drove back the cavalry on Eumenes’ left. Keeping his head, Antigonus then turned his cavalry to threaten Eumenes’ infantry from behind, forcing them to break off their pursuit of his (Antigonus’) defeated infantry. This enabled officers sent by Antigonus to regroup and reorganize his infantry and left wing cavalry, and bring them forward again to rejoin Antigonus and the right wing cavalry. As Antigonus thus reorganized his army to renew the fight, Eumenes did the same, a few hundred yards separating the two armies. By the time they were ready, however, it was nearly midnight.

Both armies were exhausted after a night of marching and a day of fighting, and both commanders decided against trying to fight again. Eumenes led his army back, intending to occupy the site of the battle—a standard sign of victory; but once it was marching Eumenes’ army refused to stop at the site of the fight and insisted on returning all the way to the comforts of their camp. Antigonus had his men better in hand: once he saw that Eumenes’ army had withdrawn completely, he led his men forward and encamped on the site of the battle, taking up the dead and wounded. Far more of these were Antigonus’ men—nearly eight thousand all told—while Eumenes’ casualties amounted to under fifteen hundred. Thus, though both sides claimed victory in this drawn battle, it was clear that Eumenes’ side had the advantage. Antigonus buried his dead at dawn, and looked after his wounded and the rest of his army, while informing heralds from Eumenes’ army that he would hand over the enemy dead and wounded on the next day. In fact, however, he led his army away under cover of darkness into southern Media, where he put them into winter quarters. Eumenes, after taking care of his own dead and wounded, continued his march into Gabiene and there settled his army too into winter quarters.

The year 316 thus came to a close with no outcome to the contest, and with Antigonus getting impatient to finish it off and return west. Through scouts or other informants he learned that Eumenes had dispersed his army widely into separate camps for the winter, and perceived in this an opportunity for a surprise attack. The standard route from his winter quarters to the region where Eumenes was quartered was more than three weeks’ march; but the distance was much shorter as the crow flies: a mere nine days’ march through a trackless, waterless desert would bring Antigonus’ army into Gabiene. This desert was overlooked by hills on all sides, and in order to keep the element of surprise an army marching through it would have to avoid lighting fires at night. Just after the winter solstice, as the year changed from 316 to 315, Antigonus announced that he intended to invade Armenia to the northwest and ordered his troops to prepare ten days’ water and rations for a swift march. He then set out across the desert towards Gabiene instead, intending to roll up Eumenes’ army piecemeal in their scattered winter camps. Unfortunately, the winter nights in the desert were so cold that Antigonus’ soldiers disobeyed his orders not to light fires; their fires were observed from the surrounding hills and reported to Eumenes, who realized he was about to be disastrously outmaneuvered. Rising to the occasion, he gathered the troops nearest the desert, several thousand strong, and ordered them to build enough fires on the hills overlooking the desert to suggest an encampment of tens of thousands of men. When these camp fires were, in turn, reported to Antigonus, he assumed that Eumenes had already concentrated his army and at once changed his line of march into inhabited lands to recuperate his army before confronting Eumenes. This of course gave Eumenes time to gather his army, and the two forces drew together for another major confrontation in Gabiene.

The resulting battle, fought early in 315, took place on a broad plain with a saline, dusty topsoil. Antigonus drew up his army as at Paraetacene, with his strongest cavalry on the right, light cavalry in a withdrawn position on his left, and his infantry in between with orders to hold their ground and look for the right wing cavalry to win the battle. Eumenes decided to take his station on his left this time, with his best cavalry, to counter Antigonus’ right wing cavalry. He relied on his infantry, with the experienced Silver Shields, to win the battle for him. In front of both armies was a skirmishing line of light infantry interspersed with elephants, and when these engaged each other, they threw up such dust clouds that the battlefield became obscured and the action hard to follow. The Silver Shields nevertheless led a charge of Eumenes’ infantry and routed the fearful infantry of Antigonus opposed to them. As Antigonus’ infantry fled, pursued by the Silver Shields, however, Antigonus charged Eumenes’ left wing with his cavalry and, despite fierce resistance from Eumenes’ personal guard, broke through and forced Eumenes’ left wing into flight. Eumenes managed to extricate his guard and rode to join his right wing cavalry, which had not yet been engaged. Despite all Eumenes could do, however, when his light cavalry saw Antigonus’ heavy cavalry coming at it in clouds of dust, they turned and retreated. That left Antigonus free to attack Eumenes’ victorious infantry from behind, abruptly halting their pursuit of his own infantry. Led by the highly disciplined Silver Shields, Eumenes’ infantry organized themselves in a square formation and counter-marched to link up with Eumenes and the light cavalry forces of his right wing, commanded by Peucestas, leaving Antigonus and his cavalry in control of the field of battle.

So far, the battle seemed like another draw, just as the one fought at Paraetacene in the previous year. But there was a twist to the tale. When his army had reunited some distance from the original battle site, Eumenes urged his men to reform and renew the fight, arguing that victory was within their grasp thanks to the crushing of Antigonus’ infantry. Peucestas and the light cavalry, however, refused to confront Antigonus’ heavy cavalry, instead insisting that the army withdraw to their camp to rest and consider their position. That proved to be impossible, however. When Antigonus noted the huge obscuring clouds of dust thrown up by the screens of skirmishers, he had taken advantage of the lack of visibility to send a special detachment of cavalry to ride unobserved around the site of battle and capture Eumenes’ camp by surprise. In that camp were the wives, children, and life savings of Eumenes’ soldiers. As soon as they learned of this, the Silver Shields decided they had had enough. They sent representatives to negotiate with Antigonus for the return of their families and property. Antigonus was willing enough: all they had to do was switch sides and hand over Eumenes. The unwary Eumenes was suddenly arrested by his own elite soldiers, who carried him off to Antigonus’ camp and handed him over, ending this campaign. Antigonus was now the clear winner. The other eastern satraps either made their own peace with Antigonus on the best terms they could, or fled back to their provinces with whatever troops would follow them. A few, most notably the Silver Shields’ commander Antigenes, were arrested and killed.

After some deliberation, Antigonus decided that Eumenes could not be trusted and was too dangerous to leave alive. Despite their old friendship, therefore, Eumenes was executed; but many of his friends and subordinates, like Hieronymus and Peucestas, found positions in Antigonus’ entourage. Antigonus spent the spring and summer of 315 reorganizing the eastern part of the empire so as to pose no further threat to him, his chief goal being to return to the west as soon as possible. Reliable officers were sent to take over those provinces whose satraps had been killed; the governors who had safely escaped back to their provinces were cowed and offered no further threat. To oversee the eastern provinces Antigonus decided to leave a general with a strong force in Media. For this post he judged that Peithon could not be trusted: he was arrested and executed on charges of disloyalty, and a loyal friend named Nicanor was established in the post instead. Antigonus then took the royal treasure at Ecbatana and moved southwest to Susa. There the gates to the citadel were now open to him, and he took possession of the great royal treasure there too. Having scooped up all the remaining great Persian treasures, Antigonus was able to convoy to the west under his charge the stupendous sum of thirty thousand talents of gold and silver. This, along with his army, formed the secure basis of his power, enabling him to pay armies and administrators, build fleets, establish cities and forts, and bring in colonists and garrisons as he saw fit. Arriving in Babylonia, he decided that Seleucus, like Peithon, was too independent to be trusted, and set about deposing him. More wary than Peithon, Seleucus saw the blow coming and fled with his personal entourage to take refuge with Ptolemy in Egypt.

At the end of 315 Antigonus returned to Syria with all of the Asian empire of the Macedonians, in effect the former Persian Empire, under his complete control, making him the great winner so far of the wars of the succession and the most powerful by far of Alexander’s Successors. His armed forces had swollen to in excess of eighty thousand men, with outstanding cavalry and a solid core of Macedonian infantry. His wealth was vast and in addition to his treasure we learn that his annual income from his lands amounted to some eleven thousand talents. But new challenges awaited. In the west, Cassander had defeated Polyperchon and established himself as ruler over Macedonia and most of southern Greece. In late 317 Polyperchon had made the mistake of leaving Macedonia to confront Cassander without taking king Philip Arrhidaeus with him. The young queen Eurydice had promptly taken control of her husband and the government, deposing Polyperchon as regent and siding with Cassander and Antigonus. That prompted Alexander’s mother Olympias, concerned for her young grandson Alexander IV, to leave her self-imposed exile in Epirus and enter Macedonia with an army. Eurydice gathered troops to meet her and there occurred the unique spectacle, in western Macedonia, of two armies confronting each other, each of which was commanded by a woman. In the event Eurydice’s Macedonians refused to fight against the mother of Alexander, and the young queen was defeated and captured along with her husband. In control of Macedonia at last, Olympias proceeded to lose all the good will she had by instituting a reign of terror. Eurydice and her husband, the hapless king Philip Arrhidaeus, were brutally executed; relatives and adherents of Cassander were hounded and executed; and even the bones of Cassander’s deceased relatives were dug up and their graves desecrated.

When Cassander returned at last to Macedonia at the head of a large army, the Macedonians would not fight for the frightful Olympias, who took refuge in the fortified city of Pydna where she was besieged and starved into surrender. Cassander arranged for the relatives of Olympias’ victims to take revenge by killing the old queen, and himself recovered the bodies of Eurydice and Philip Arrhidaeus for royal burial, probably in the famed tomb II at Vergina whose magnificent burial goods are now displayed in the museum built over the tombs. Cassander took charge of the surviving king, the child Alexander IV, and had him placed under “protective custody” with his mother Roxane in Amphipolis, there to be properly educated for his future position as ruler, so he let it be known. Meanwhile, 315 found Cassander in full control of Macedonia and a formidable ruler. Polyperchon had retreated with the remnants of his forces to Aetolia and the western Peloponnese, there to live the life of a minor dynast and mercenary commander.

Ptolemy had used the years of Antigonus’ absence in the east to secure his control of Egypt, build up his capital city of Alexandria, seize control of the Cyrenaica in Libya, and extend his power over a buffer zone of Palestine (including Phoenicia) and Cyprus. With Antigonus’ return to the west, Ptolemy himself returned to Egypt after establishing strong garrisons in the cities of Phoenicia and Palestine, and prudently removing the fleets of the Phoenician cities to Egypt where he could control them. Ptolemy and Cassander had been in touch with each other, and with another still independent dynast, Lysimachus in Thrace, and decided that Antigonus was so strong that, for the security of all, he must be cut down to size. Along with the refugee Seleucus they had prepared a common ultimatum which was waiting for Antigonus when he arrived in southern Syria. This ultimatum portended future strife and warfare.

3. CREATING THE EMPIRES OF THE HELLENISTIC WORLD

With Polyperchon’s brief and failed regency brought to an end, the wars of Alexander’s generals had resulted in the division of Alexander’s realm into three major “empires”: Antigonus ruled over western Asia (essentially the former Persian Empire); Ptolemy controlled Egypt, with its immense wealth and matchless grain resources; and Cassander held Macedonia and its neighboring lands, the source of the Macedonian and Greek manpower without which there could be no empire. This division of lands was to prove permanent, at least until the advent of the Romans in the second and first centuries BCE, though there was still much fighting to be done, and both western Asia and Macedonia changed ruling dynasties before things finally settled down after 272. But it was the organization of empires and systems of rule that was the most crucial feature of the years after 315 down to the 280s and 270s. These are the decades when the governing structures of what we call the Hellenistic World were established, in western Asia by Antigonus and Seleucus, in Egypt by the first two Ptolemies, and in Macedonia by Cassander and Antigonus Gonatas.

In between fighting their numerous wars and battles, in fact, Antigonus, Seleucus, and Ptolemy expended enormous effort in organizing the conquered lands in Asia and Egypt into stable empires based on Greek civilization. They reorganized the old provinces, in many cases dividing them up into smaller more manageable provinces governed by military governors with the title strategos (general). They revamped the tribute payment system, establishing sub-provinces called chiliarchies (by Antigonus) or eparchies (after Seleucus took over), each ruled by a regional sub-governor responsible for local security and tribute collection. They settled tens of thousands of veteran soldiers in military colonies, many named after cities of Macedonia and Greece, such as Pella, Cyrrhus, Europus, or Larissa, where they functioned as local security forces and their sons and grandsons were eventually recruited into the imperial armies. Most important of all, they imported many tens if not hundreds of thousands of Greek (or at least Greek-speaking) colonists into Asia and Egypt who were settled in new Greek cities. Frequently these cities were named after the kings and other members—including female members—of the royal dynasties, and by the second century BCE, instead of Athens, Sparta, and Corinth, the leading cities in the Greek world were Alexandria in Egypt, Antioch (formerly Antigoneia) in Syria, Seleucia on the Tigris, and many other cities with dynastic names such as Ptolemais, Arsinoeia, Laodiceia, Stratoniceia, or Apamea. For some six centuries the near east was dominated by the new urban civilization we call Hellenistic, a melding of classical Greek culture with elements of native Asian and Egyptian cultures. This vast colonization program, organized primarily by Antigonus, Seleucus, and Ptolemy—though built on and continued by their early heirs—was undoubtedly the most important work carried out by Alexander’s Successors, and deserves careful investigation.

It needs to be recognized what a vast undertaking the colonization program of the great Successors of Alexander was. In excess of one hundred thousand people were transported across the Aegean and eastern Mediterranean from Greece and other Balkan territories to find new homes in western Asia and Egypt. The human and political geography of western Asia and Egypt were thereby fundamentally changed, as was their culture. Thanks to the city-building enterprises of Antigonus, Seleucus, and Ptolemy, Greek urban life and culture became the dominant way of life and culture, and Greek the universal language. This process required immense organizational skills and a vast expenditure of wealth. Thousands and thousands of people—women and children as well as men—could not simply be told to make their ways from their ancestral homes to new lands, and then parked there to organize themselves into cities and thrive or die as luck dictated. These people had to be transported, they had to be fed and cared for during transportation, they had to be assisted to organize themselves in their new homes, they needed all sorts of assistance to build their new houses and urban infrastructure. That process of building would certainly take years, during which they would continue to need assistance in food and supplies of all sorts, as well as in technical expertise and labor for all of the building that must be done.

Unfortunately, our ancient sources tell us very little about this colonizing process: we only see the result. But from the few sources that do offer some detail, a picture of the process can be reconstructed. We may take as an example the city of Antigoneia on the Orontes, founded around 307 by Antigonus the One-Eyed, and later (after 301) moved a few miles downstream and re-founded as Antioch by Seleucus. The late antique chronicler John Malalas, a native of Antioch, reports in his Chronographia at book 8.15 that the population of Antigoneia was mostly made up of Athenians but with some Macedonians, 5,300 men in total. The source of the Macedonians is clear: Antigonus had thousands of Macedonian soldiers in his army, whom he settled as they grew older in numerous cities and garrison colonies all around western Asia. But how did the four thousand or more Athenians, perhaps even as many as five thousand, get to Syria and the banks of the River Orontes? And those numbers just account for the men: we must surely assume that many if not most of these Athenian settlers had wives and children too. At a very conservative guess we can assume that more than ten thousand people had to be transported from Athens to Syria to found this city. To begin with this issue sheds a new light on Antigonus’ decision at the beginning of 307, as we shall see below, to send his son Demetrius with a huge expeditionary force to “liberate” Athens from the rule of Cassander and restore the traditional democracy there. That gave Antigonus the ability and popularity to request Athenian settlers for his new foundation. It also gave him the means of transporting them.