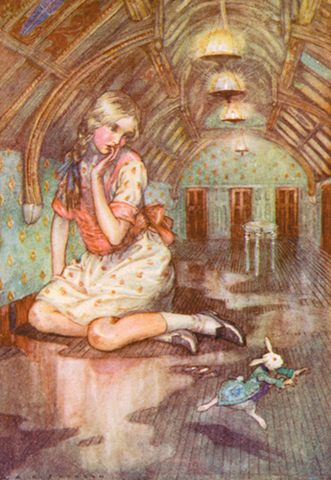

It flashed across her mind that she had never before seen a rabbit with either a waistcoat-pocket, or a watch to take out of it.

Proserpine (Persephone), 1874, by Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

THE WHITE RABBIT Lewis Carroll’s fairy tale about a young girl’s descent underground is literally the oldest story in the world. Originally entitled Alice’s Adventures Under Ground, Carroll’s fairy tale is based on the story of the Mesopotamian goddess Inanna’s descent into the underworld realm of the dead, the oldest recorded myth in world literature and one that is retold in the Babylonian myth of Ishtar and the Egyptian myth of Isis.

The story is best known as that of Persephone, the Greek goddess of spring whose descent into the underworld was one of the most popular mythological motifs in art and literature throughout Carroll’s lifetime, indeed the entire Victorian age.

The myth of Persephone begins in an idyllic meadow with her older sister, the earth goddess Demeter, who—in the scandalous way of gods and goddesses—is also her mother. Persephone is idly daydreaming and picking flowers when she falls down an infinitely deep fissure into a subterranean world. She experiences many adventures and trials, but at last escapes and returns to her sister Demeter’s arms.

The frame story of Alice’s Adventures—in both the Under Ground and Wonderland versions—mirrors Persephone’s journey. In Alice’s case, she is sitting in an idyllic meadow with her (rather motherly) older sister, Lorina, and—while idly daydreaming and considering the picking of flowers—drifts into a dream wherein she falls down an infinitely deep hole into a subterranean world. Like Persephone, she experiences many adventures and trials, but finally escapes from the underground world and returns to the arms of her sister Lorina.

Mysteries of the Goddess: Alice as “Queen of the May.”

But what of the White Rabbit? As everyone knows, the fairy tale properly begins with a little girl named Alice chasing a White Rabbit down a rabbit-hole into a strange and mysterious Wonderland deep beneath the earth. Why would Lewis Carroll choose a white rabbit as Alice’s guide into this underground world?

In classical times, pilgrims initiated into the Mysteries of the Goddess, dressed in white and wearing wreaths of flowers, entered her temple sanctuary at Eleusis where they re-enacted the descent and eventual celebrated return. Carroll alludes to this ancient pilgrimage in the prelude poem’s final line: “Like pilgrim’s wither’d wreath of flowers / Pluck’d in a far-off land.” Furthermore, and not coincidentally, he photographed Alice Liddell as “Queen of the May,” dressed in white and crowned with a garland of flowers like an initiate into the Mysteries.

In this context, the White Rabbit is a clear example of what is known in most of the world’s mythologies as a psychopomp, or guide of souls. These are creatures, spirits or deities who escort newly deceased souls (and sometimes the souls of dreamers) to the underworld, where they are to be judged by its rulers. In a few cases, such as that of Persephone, these souls are allowed to return to the world of the living. At various times and in different cultures, psychopomps have been associated with a variety of animals.

To some degree Carroll must have been drawing on the Celtic tradition of the Phooka, a trickster animal spirit and transformer who often takes the shape of a rabbit. The Irish Phooka is a guide to the fairy realm. (In its Welsh form, it is known as a Puca, from which Shakespeare derived his fairy spirit Puck.) And we know from his diaries that upon viewing Edwin Landseer’s painting Scene from A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Carroll observed “there are some wonderful points in it … the white rabbit especially.” And remarkably, next to the white rabbit is the miniature figure of Puck.

However, the most likely reason for Carroll’s choice of the rabbit is linked to his inspiration for Alice’s adventure: the myth of Persephone, the goddess of spring, and even more obviously, her British manifestation, the goddess Eostre. Both goddesses were commonly portrayed in the company of a rabbit, the symbol of spring and fecundity. Although we seldom think of the ancient symbolism of this emblematic creature, it is clearly present today. After all, our Easter rabbit is a direct descendant of Eostre’s rabbit.

Eostre, the Saxon goddess of Spring, accompanied as usual by a rabbit.

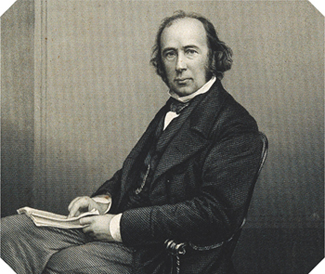

Still, the Wonderland White Rabbit with his pocket watch and waistcoat is an original creation, and like all the creatures in Wonderland has a historical above-ground human counterpart. The real-life Oxford White Rabbit was Alice Liddell’s family physician, DR. HENRY WENTWORTH ACLAND (1815–1900). Dr. Acland was Oxford’s Regius Professor of Medicine who on at least one occasion brought Alice “back to life.” Like the White Rabbit who was in service to the Duchess and the King and Queen of Wonderland, Dr. Acland had served as physician to royalty: to Queen Victoria, Prince Albert and the Prince of Wales (on his tour of Canada). Like the White Rabbit, the royal doctor was often seen checking his pocket watch before rushing off to his next appointment.

Dr. Acland was also a noted anatomist and a social reformer who, in the wake of numerous epidemics in Oxford, developed an obsession with public sanitation and underground sewage systems. Consequently—and again like the White Rabbit—Dr. Acland was frequently seen climbing down into holes in the ground on his regular inspection of drainage tunnels.

The man behind the White Rabbit: Dr. Henry W. Acland.

“There are some wonderful points in it,” said Carroll: Scene from A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Titania and Bottom, by Edwin Henry Landseer, circa 1850.

THE ROSICRUCIAN RABBIT Alice’s descent down a rabbit-hole into Wonderland has an historic precedent in the publication of Cabala, Mirror of Art and Nature: in Alchemy. Published in 1615 by Steffan Michelspacher, it was dedicated “to the Brotherhood of the Rosy Cross; than which in this matter let no fuller statement be desired.”

The Rosicrucian Brotherhood was a secret society whose stated mission was to advance and inspire the arts and sciences through the study of symbolic and spiritual alchemy. Initiates were instructed to undergo certain rites of passage that resulted in the attainment of ancient esoteric knowledge. Rosicrucianism arose in Bohemia in the early seventeenth century, and rapidly spread throughout Europe. In Britain, it was particularly influential in Oxford.

In the Cabala we discover for the first time in literature and art the pursuit of a rabbit down a rabbit-hole as a major theme in a quest. One of this book’s elaborate engravings reveals that 250 years before Alice ducked down a rabbit-hole, Rosicrucian initiates were being instructed to pursue a fleeing rabbit into a similar mysterious underground world—a theme repeated in later Rosicrucian documents.

Throughout the Cabala we find the acronym “V.I.T.R.I.O.L.” This stands for the Latin “Visita interiora terrae rectificandoque invenies occultum lapidem verum medicinalem,” an instruction to the Rosicrucian initiate to “visit the interior of the earth and by rectifying discover the true medicinal stone”—the philosopher’s stone. And through text and storyboard illustration, the initiate is encouraged—like Alice—to “visit the interior of the earth” and to “ferret out” the rabbit. In this context it is significant that the White Rabbit of Wonderland is fearfully certain that he will be hunted down: “as sure as ferrets are ferrets!”

The Rosicrucian notion of a secret repository for universal knowledge was an inspiration not only for the Freemasons Brotherhood and the Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge but also for Oxford’s Ashmolean Institute and Museum, opened in 1683. Carroll was an active member of the institute, and the Ashmolean possessed one of the world’s great Rosicrucian alchemical libraries. Among the many hermetic books, the Cabala was one that would have been of supreme interest to the young Christ Church sub-librarian Charles Dodgson.

As the hermetic scholar Joscelyn Godwin has observed, there probably was no such thing as “a card-carrying member of the Brotherhood,” but there were a multitude over the next three centuries “who shared the ideals set forth in its manifestos.” Charles Dodgson—and his alter-ego Lewis Carroll—were certainly numbered among this company.

Other symbolic images in the Cabala reappear in Wonderland. In the foreground of the engraving, we see an alchemist’s initiate, blindfolded to symbolize a trance, or dream state. The figure to his left is the initiate’s double, which is his dream-self. Like Alice’s dream-self pursuing the White Rabbit, the initiate’s dream-self double pursues a mercurial rabbit down a hole that leads into a vast and mysterious underground world beneath a mountain.

As in Alice in Wonderland, the Rosicrucian initiate discovers a secret underground great hall for the testing of initiates. The step-pyramid that forms the foundation of the underground hall is labelled with the seven steps of the alchemical process. However, these are in the wrong sequence.

It is up to the initiate by trial and error to “rectify” and eventually understand the alchemical process, then to put them in the proper order. Similarly, in Wonderland’s underground hall, Alice must learn the proper order of actions so that she may use her golden key and enter the garden.

The Cabala alchemist’s hall is under a mountain, surmounted by seven gods/planets/metals, and is reminiscent of another of the Rosicrucian legends: the quest to discover the subterranean tomb of Christian Rosencrantz (“Christian Rose-Cross”). This seven-sided tomb was placed in an underground chamber that, like Wonderland’s hall, was fitted with many doors and contained many symbolic objects: magic looking glasses, telescopes, sacred books and keys.

If we look carefully at the Cabala engraving, we can see on the pinnacle of the Mountain of Alchemy the true goal of the initiate: a miniature rose garden with a hedge around the fountain of Mercury. This garden of the Rosy Cross is the same garden of “bright flowers and those cool fountains” that is Alice’s goal in Wonderland: the rose garden of the King and Queen of Hearts.

From the Cabala: Mountain of Alchemy, topped by a rose garden.

FIBONACCI’S RABBIT-HOLE At the beginning of Wonderland, we are told that Alice is “considering in her own mind … whether the pleasure of making a daisy-chain would be worth the trouble of getting up and picking the daisies, when suddenly a White Rabbit with pink eyes ran close by her … and fortunately [she] was just in time to see it pop down a large rabbit-hole.”

Note how Carroll has Alice “in her own mind” gathering “a daisy-chain.” As any naturalist or mathematician will tell you, daisies are unique among common flowers in having 13, 21 or 34 petals—that is, three Fibonacci numbers in sequence.

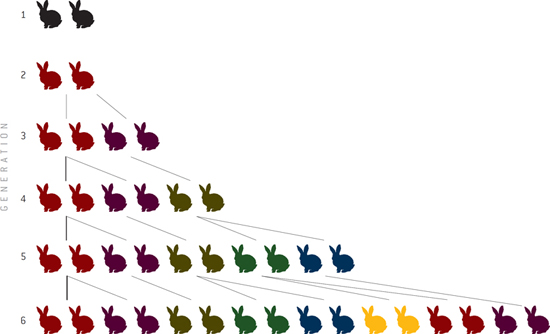

In Fibonacci’s Liber Abaci, or “Book of the Abacus” (published in 1202), we learn that the discovery of this sequence arose from a mathematical competition in which this problem was set: “Beginning with a single pair of rabbits, if every month each productive pair bears a new pair, which becomes productive when they are one month old, how many pairs of rabbits will there be after a year?”

Fibonacci’s rabbit puzzle.

The result is a sequence of numbers, each of which is the sum of the previous two numbers, starting with 0 and 1. Thus, we have an infinite series that continues with:

1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89…

This pattern takes on significance if we write the numbers as decimal fractions:

1/1 = 1.000, 2/1 = 2.000, 3/2 = 1.500, 5/3 = 1.666…, 8/5 = 1.600, 13/8 = 1.625…, 21/13 = 1.615…, 34/21 = 1.619…, 55/34 = 1.617…, 89/55 = 1.618… and so on.

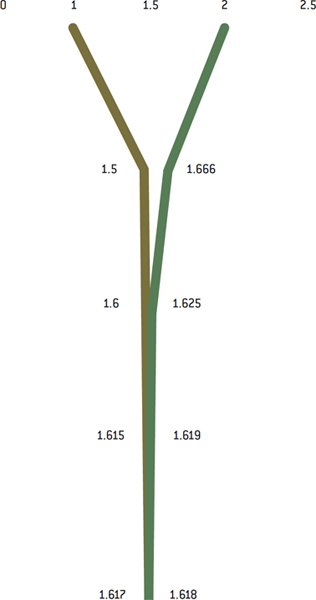

Now, with the ratio 89/55 = 1.618 we come to one of the most important and fascinating dimensions of the Fibonacci numbers. The further down we travel with this sequence, the closer two consecutive Fibonacci numbers divided by each other will approach what was known in antiquity as the golden ratio: approximately 1:1.618 (or, slightly more fully, 1:1.6180339887… onward to infinity).

Since the time of the ancient Greeks, this ratio was believed to be the most aesthetically perfect proportion for the human body, and it has been used in the creation of art, architecture and music. In geometry it was manifest in the golden section, golden rectangle, golden triangle and star pentagram. Fibonacci numbers combined with the golden spiral dictate the shape and growth of patterns in pine cones, pineapples, sunflowers, seashells, trees and honeycombs. Known by the symbol for the Greek letter Φ (phi), it has been called “Nature’s number.”

All these aspects of mathematics related to golden ratios, sections, series and so on were diligently taught to mathematics students throughout the nineteenth century and were seen as the aesthetical and logical foundation to all the arts and sciences. However, it was only during Lewis Carroll’s Victorian childhood that the anecdotal aspect of Fibonacci’s discovery through the breeding of rabbits became a well-known (and historically accurate) account that was taught to students of mathematics.

It is said that mathematics makes the invisible visible. So, let us look at Carroll’s rabbit-hole through a mathematician’s eyes. Let us examine a comparable infinite sequence in that popular classic text Excursions in Number Theory (1966) by C.S. Ogilvy and J.T. Anderson. There, the authors chose to create a graph or lattice using irrational √2 ratios as alternating consecutive fractions:

1/1 = 1.000, 3/2 = 1.500, 7/5 = 1.400, 17/12 = 1.416…, 41/29 = 1.413…, 99/70 = 1.414…

This creates the walls of a corridor that visually demonstrate how this convergent sequence progresses infinitely toward the exact value of the √2:

1:1.41421568… and onward to infinity.

If we can imagine peering down that corridor, Ogilvy and Anderson explain, “then if you were to look in that direction from the origin you would, theoretically, have a clear view … all the way to infinity.”

If we create a similar graph or lattice using Fibonacci ratios as alternating consecutive fractions in an infinite convergent sequence, we end up with a graph that replicates Carroll’s description of Alice’s descent to Wonderland through this gap in time and space: an infinite sequence of convergents oscillate to form the walls of this rabbit-hole. “Would the fall never come to an end?” The answer is both no and yes.

We too have constructed a tunnel with a clear view all the way to infinity. So we could answer that Alice’s fall is infinite and will never end; or we may answer that it will end in what is known as an “ideal point” at infinity—which in this case is the infinite golden number, or the golden ratio known as Φ. And as this is, after all, a fairy tale, we must conclude that this “ideal point” is Wonderland: a land existing in that infinite dimension that is the human imagination—where Alice discovers the golden key: Φ.

Martin Gardner, in his Annotated Alice, compares Alice’s long fall to “the famous ‘thought experiment’ in which Einstein used an imaginary falling elevator to explain certain aspects of relativity theory.” Certainly, Alice’s descent down the rabbit-hole does appear to be some sort of surreal “thought experiment” wherein Carroll’s “dream child” is conscripted into a mathematician’s demonstration.

In this context, and given Carroll’s love of anagrams, one might wonder why—as Alice falls through this pre-Einstein wormhole in space and time—he has his heroine clutch at an empty jar labelled “ORANGE MARMALADE.” However, if one accepts the proposition (made in the introduction) that Wonderland was constructed by Carroll as an analog of the world and all its secrets, then one might reply that perhaps it is not entirely coincidental that unscrambled, the label reads: “AM ANALOG DREAMER.”

Then, too, there is the White Rabbit’s belief that he is always a little late. This may be a joke about Oxford’s insistence on keeping “Oxford Time” as opposed to Greenwich Mean Time. The Tom Tower clock at Christ Church was set according to Oxford’s longitudinal position, which is technically five minutes later than Greenwich Time. This made little difference until 1844, when the first railway was put through to Oxford, and suddenly Oxford time came into conflict with the accepted national standard time. Consequently, if Dr. Acland was setting his watch by Oxford time, he might find himself constantly late for his appointments with the Queen in London.

Besides having real-life above-ground counterparts for each of its fairy-tale characters, Wonderland also has real-life above-ground counterparts for each of its locations. As we have seen, the fairy tale begins in a real-life location: on the banks of the Isis. However, what can Alice expect to discover in the underground world at the bottom of the rabbit-hole?

After her long fall, we are told that Alice lands with a “thump! thump!” but is otherwise unhurt. Immediately she leaps up and chases the White Rabbit down a passage and around a corner into a great hall lit by a row of lamps hanging from the roof. Upon entering Wonderland’s hall in pursuit of the White Rabbit, Alice finds she is alone, and although there are many doors around the hall, they are all locked.

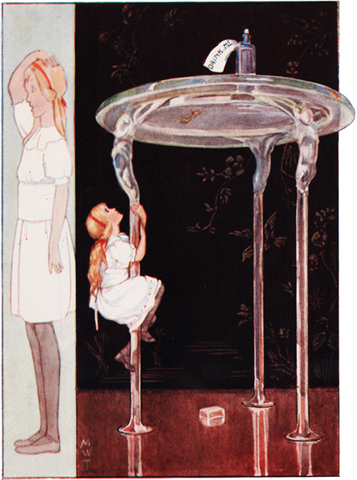

On a second inspection, Alice discovers a glass table on which she finds a tiny golden key that unlocks a little curtained door leading into “the loveliest garden you ever saw.” But the door is too small for Alice to even get her head through. How will she get to the garden? Why does she wish to gain entry to the garden? And what is this great hall?

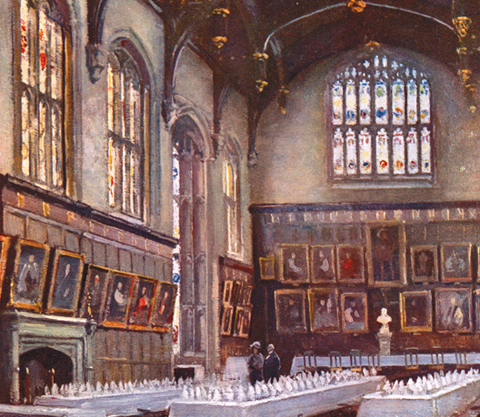

The Great Hall of Christ Church is the above-ground model for the great hall of Wonderland. Christ Church boasted one of the largest and grandest ancient halls in Britain. Built by Cardinal Wolsey in 1524, for nearly five centuries it has been the dining hall for students and faculty. Its walls are lined with portraits of its deans and famous graduates. It has been the scene of many grand dinners with notable heads of state and royalty. It has also been used as a location in numerous films, including as the Great Hall of Hogwarts in the Harry Potter series.

The Great Hall (where portraits of Dodgson and Dean Liddell now hang).

BEHIND THE CURTAIN As a classicist and a mathematician, Carroll has created an initiation hall in Wonderland comparable to that of the most ancient cult of mathematicians, the Pythagoreans. This explains the symbolic meaning of the hall’s curtained door. Pythagoreans had two categories of followers: the exoterikoi (exoteric) and the esoterikoi (esoteric); that is, “before the curtain” and “behind the curtain.” The exoterikoi were known as the akousmatikoi (listeners), and they were permitted to hear the master’s lectures only in the outer sanctum of the temple. The fully initiated esoterikoi were known as the mathematikoi (learners), and they were allowed to pass through the curtained door into the inner sanctum where the mysteries were fully revealed.

Alice very much wishes to pass through the curtained door as one of the initiated mathematikoi, but first she is put through a series of tests. To gain entry, she must consider “in her own mind” whether it “would be worth the trouble” of putting together a chain of reasoning: Alice’s metaphoric “daisy-chain.” The neophyte begins with this riddle of the golden key and the curtained door: it is a riddle about ratios and proportions and the proper sequential order.

Throughout the Wonderland adventures, Alice and the narrator use the phrase “at any rate.” In the Wonderland hall, we are told, the golden key “at any rate” will open only the tiny door, and that the passage behind door is the size of a “rat-hole” (a typical Carrollian riddle: rat-o = ratio), which explains why the golden key—as the golden ratio [1/Φ = 1 + Φ = Φ]—fits the lock of the curtained door.

Although Alice can open the curtained door with the golden key, the door and the passage beyond are so small that “she could not even get her head through the doorway.” Disappointed, Alice makes a rather peculiar wish and observation: “Oh, how I wish I could shut up like a telescope! I think I could, if I only knew how to begin.” She returns to the glass table, where she hopes to find “at any rate a book of rules for shutting people up like telescopes.”

One explanation for this wording is that Alice is, in fact, looking for a book of logarithms: a book of mathematical tables that are used for calculating exponential rates of expansion or contraction—a process that might theoretically be used for “shutting people up like telescopes.”

Perhaps Alice can’t find this book of logarithms because it is actually “the book her sister was reading” before she went down the rabbit-hole—a book that Alice summarily dismissed: “what is the use of a book … without pictures or conversations?” It now appears that this book of rules and numbers would be very useful in resolving problems with ratios and proportions.

Failing to discover a book or another key, Alice does find a bottle labelled “DRINK ME.” When she drinks from it, she shrinks to just ten inches, and exclaims: “What a curious feeling! I must be shutting up like a telescope.” Subsequently, she eats a cake in a glass box labelled “EAT ME,” and is again alarmed when she grows into a “great girl” some nine feet tall. Once again Alice compares this process of expansion and contraction to the opening and closing of a telescope: “ ‘Curiouser and curiouser!’ cried Alice…‘now I’m opening out like the largest telescope that ever was!’ ” Why is Carroll repeatedly using the mechanics of a telescope? What is he hinting at?

In mathematics, the “telescoping series rule” has a specific meaning in calculus that could be applied to Alice’s attempts to control her size. Calculus is the mathematics of change, and the manipulation of the infinitely large and the infinitely small. These are exactly the problems Alice is confronted with in Wonderland.

Alice is on the right track when she says, “Oh, how I wish I could shut up like a telescope! I think I could, if I only knew how to begin.” The telescoping series rule appears to be what she requires. It is the formula for determining to what number a convergent telescoping series converges.

This is one of the only two common rules in calculus where you can determine what a convergent series converges to. The other rules for determining convergence or divergence do not allow you to do this—and, in Alice’s case, would result in uncontrolled and comic shifts in size and proportion.

Calculus takes the regular rules of algebra and geometry and applies them to fluid, evolving problems. If Alice applies these rules, she may eventually overcome the many fluid and evolving problems she encounters as she passes through Wonderland’s mathematical maze.

Strangely enough, in Dodgson’s time, resident undergraduates at Christ Church were not required to attend classes or meet with tutors. They were, however, required to take a certain number of meals in the hall as a qualification for graduation. The Great Hall was seen as a kind of waiting room where undergraduates had to abide until they were sufficiently prepared for a viva voce, or oral examination, before a panel of eccentric tutors. Successful candidates would then be granted graduate degrees and entry into a life in the “gardens of academia.”

In Wonderland, Alice is confronted with a comparable scenario. Like the Christ Church undergraduate, she is compelled to loiter in the great hall, where she consumes a requisite number of peculiar meals and endures viva voce interrogation by a number of eccentric tutors before learning how to use her golden key to gain entry into “the loveliest garden you ever saw.”

Wonderland’s hall is here: Temple of Ceres at Eleusis, by Joseph Gandy, 1818.

On the mythological level, the counterpart to the Wonderland hall is the great hall in the Temple of Demeter-Persephone at Eleusis. Known as the Telesterion, or Hall of the Initiates, this was where all Eleusinian pilgrims gathered. Here they were tested on their knowledge of the procedures of the Mysteries before entering a labyrinth of chambers where they witnessed miraculous tableaux or epiphanies relating to the myth of Persephone—all of which we shall find are mirrored in Alice’s adventures.

In Wonderland’s Telesterion-like hall, certain objects are displayed: the glass table with the golden key, the bottle with the label reading “DRINK ME,” the glass box with the cake marked “EAT ME”—all of which test and provoke Alice in her attempts to gain entry through the curtained door and into the inner sanctum of Wonderland’s garden.

After she fails the initial test of the golden key and the curtained door, Alice finds herself wandering through a labyrinth (exactly like the pilgrim in the Mysteries) where one tableau vivant after another is revealed: the Pool of Tears, the Rabbit’s House, the Caterpillar and the Mushroom, the Duchess’s Kitchen, the Cheshire Cat, the Mad Hatter’s Tea Party. Each tableau is a riddle that reveals an essential life lesson so Alice may eventually learn how to use the golden key to achieve her aim of passing behind the curtain and through the little door to the garden.

In the Eleusinian Mysteries, the initiate’s fast is broken by a special psychoactive drink of barley and pennyroyal called kykeon, taken in the Telesterion where certain “hiera” (sacred objects) are revealed to them, as they recite, “I have fasted, I have drunk the kykeon, I have taken from the kyste [box] and after working it have put it back into the kalathos [basket].”

The rites in the Mysteries comprised three elements: dromena (“things done”), which was a dramatic re-enactment of the Demeter/Persephone myth; deiknumena (“things shown”), a display of sacred objects; and legomena (“things said”), commentaries accompanying the display of the sacred objects.

The exact nature of these three elements—known as apporheta (“unrepeatables”)—cannot now be ascertained, as repeating them carried a penalty of death for initiates, who were sworn to secrecy. Consequently, Carroll creates his own version of a series of dramatic tableaux, rituals and sacred objects throughout Wonderland for Alice the initiate, who must follow the pattern of “things done,” “things shown” and “things said” in order eventually to emerge back into the world as an enlightened soul.

In Wonderland’s version of the Telesterion, Alice, like any prospective initiate into the Mysteries, must take the sacraments of drink and food. On the glass table she finds a golden key that opens the door to the garden. She cannot enter, though, as she is too large, and so she returns to the table. There she finds a little bottle labelled “DRINK ME,” which seems to contain some kind of psychoactive mixture very like kykeon that gives her the illusion that she shrinks almost to the point of vanishing. To remedy this, she resorts to the contents of a box labelled “EAT ME,” which is comparable to the Eleusinian kyste, whose contents “must be worked.” Alice discovers that nothing happens initially after consuming the contents of her box, until “she set to work,” and finds it causes her to grow very large.

On all levels, Alice certainly undergoes an education of sorts. However, she will have to endure a good number of interrogations and consume a number of strange meals before she is permitted to enter her garden. Indeed, her initial attempts to acquire the key to the door leading to the garden fail, literally ending in tears.

WONDERLAND’S MASONIC HALL Rosicrucianism was a major source of inspiration, and supplier of symbolism, for the highly organized Freemasons. It is not known whether Lewis Carroll himself was a Freemason; he was very diligent in keeping secrets. But we do know he was well acquainted with many high-ranking Freemasons, and from his diaries we know he purchased tickets to Masonic events and public functions. Furthermore, Carroll owned an 1851 edition of Avery Allyn’s A Ritual and Illustrations of Freemasonry Accompanied by Numerous Engravings and a Key to the Phi Beta Kappa.

Consequently, Carroll was sufficiently familiar with Freemasonry to integrate their symbolism (in a somewhat disguised form) into Wonderland. For example, from the perspective of a three-inch Alice standing beneath the Wonderland hall’s three-legged glass table with its out-of-reach golden key, we have a challenge comparable (on a grander scale) to the Freemasons’ first degree apprentice tracing board—an aide-mémoire to the fraternity’s symbols and emblems—with its three gigantic pillars (wisdom, strength, beauty) and its out-of-reach golden key hanging from a ladder. Alice looks for “another key … or at any rate a book of rules for shutting people up like telescopes”—she is much concerned with size and proportion. At the base of the ladder in the Freemasons’ tracing board is a book, and with it instruments for measuring and levelling. There are also two blocks of stone—one rough cut, one a perfect cube.

In the symbolic language of the fraternity, the ladder represents the ascent into the mysteries of Freemasonry. This ascent is achieved through the step-by-step process by which the raw ashlar or rough stone (the apprentice) is transformed into the perfect ashlar—or cubit of cut stone (the adept Alice is going through a similar step-by-step process of learning to gauge measurement and proportion.)

The three female figures in the tracing board are Hope, Faith and Charity (comparable to the three fatal sisters of the prelude poem), the virtues that both Alice and the initiate require to win the golden key. In the centre of the tracing board, above the pillar of wisdom, we see the single most famous symbol of Freemasonry: the All-Seeing Eye. This symbol represents the Great Architect of the Universe. In Wonderland, Carroll uses a verbal sleight-of-hand trick to introduce the All-Seeing Eye into Alice’s garden.

Alice finds herself too large to enter through the little door, but: “It was as much as she could do, lying down on one side, to look through into the garden with one eye.” Later, with the Lobster Quadrille, Carroll has her begin to recite the carefully worded first line of a poem: “I passed by his garden, and marked, with one eye.”

Many of Carroll’s poems contain hinting references to the Freemasons and Rosicrucians, secret societies whose language and symbols were intentionally obscure to the uninitiated. “Ode to Damon” has the subtitle “(From Chloe, Who Understands His Meaning)” and ends with: “You’ll find no one like me, who can manage to see / Your meaning, you talk so obscurely.” Compare this with the final lines of the Rosicrucian Catechism: “Why do you people speak so obscurely? / So that only the true sons of God may understand me.”

Masonic first degree tracing board, painted by Josiah Bowring in 1819.