“I move that the meeting adjourn, for the immediate adoption of more energetic remedies—”

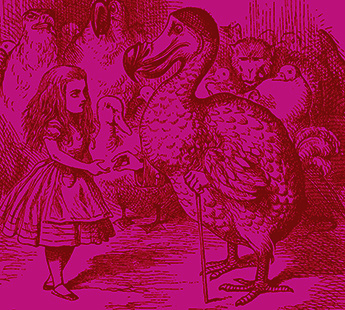

THE DODO AND THE DODGSON On the bank of the Pool of Tears, Alice finds herself emerging with a variety of birds and animals from a kind of primordial soup. They are somewhat disgruntled as they discuss how they might best dry out. Alice begins chatting with two of the birds and has the strangest feeling that “she had known them all her life.” There are hints of Darwinian evolution here (in one of Tenniel’s engravings an ape can be seen, and in Carroll’s own drawings in the Under Ground manuscript, a pair of monkeys swim in the Pool of Tears), but as the creatures all seem capable of speech, the scene is perhaps also meant as a parody of the spiritualist craze of the time. Mediums often claimed they could communicate with the spirits of departed relatives through household pets such as dogs and parakeets.

After some discussion, the Mouse decides on the best way for everyone to dry out. With the strict authority of a schoolteacher, he demands silence and proceeds to deliver the driest of history lessons.

As we have discovered, the Mouse’s lecture on the Norman kings is a direct quotation from a very boring lesson book of the time. Although the lecture is painfully dry, it does nothing to dry the wet animals, which prompts impatient remarks from the Lory, Duck, Eaglet and ultimately the Dodo.

All these creatures have real-life identities that would be easily recognized by Alice and her sisters. Indeed, Alice is quite correct in her impression that “she had known them all her life.” Two were her sisters transformed into birds: LORINA CHARLOTTE LIDDELL (1849–1930) is the Lory—that is, a lorikeet, or small parrot—while the younger EDITH LIDDELL (1854–1876) is the Eaglet.

Like the “golden afternoon” prelude poem and “The Pool of Tears,” this chapter contains several teasing private jokes meant for the Liddell sisters. The Lory-Lorina’s insistence that “I am older than you, and must know better” is reminiscent of her portrayal in the poem as “Imperious Prima” who “flashes forth / Her edict,” while the Eaglet-Edith’s curt interruption of the Dodo is entirely consistent with “Tertia” who “interrupts the tale / Not more than once a minute.”

Eaglet-Edith: Interrupted the tale not more than once a minute.

Lory-Lorina: “I am older than you, and must know better.”

If further evidence were needed, we might wish to examine the earlier Alice’s Adventures Under Ground version of the story. In it is a passage left out of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland wherein Carroll makes sure that the sisters recognize themselves in the guise of the two birds. This passage has Alice talking “to herself again as usual: ‘I do wish some of them had stayed a little longer! and I was getting to be such friends with them—really the Lory and I were almost like sisters! and so was that dear little Eaglet!’ ”

The other two birds would also be recognizable to the three sisters. The Duck was the Reverend Robinson Duckworth and the Dodo was the Reverend Charles Dodgson himself. We have proof of this with a signed copy of the 1886 facsimile edition of Alice’s Adventures Under Ground that Carroll inscribed with a dedication to Robinson Duckworth: “From the Dodo to the Duck.”

ROBINSON DUCKWORTH (1834–1911) was a friend and colleague of Dodgson’s at Oxford. He was a Fellow of Trinity College who went on to a distinguished career in the church. He eventually became royal chaplain to two monarchs, Queen Victoria and Edward VII. During the Wonderland years, he was a famously fine ecclesiastic singer who often sang to the Liddell sisters on their expeditions with Dodgson. This is acknowledged in the Under Ground version, in a passage in which Alice comments: “How nicely the Duck sang to us as we came along through the water.” Ducks are not generally known for their fine singing voices, but the Duckworth proved to be the exception.

Robinson Duckworth: Dodgson the Dodo acknowledged him as the Duck.

THE OXFORD DODO The Oxford University Museum’s Dodo was in Carroll’s time believed to be the only surviving relic of this famously extinct bird. The flightless Dodo was the world’s largest member of the pigeon family: a giant dove with the weight of two large domestic turkeys. It was first recorded in 1598 by Dutch sailors, who called it the Dodoor because it appeared to be a giant version of the Dodaer, or Dutch little grebe.

The Oxford Dodo was brought to London live from its native Mauritius sometime before 1638. It was exhibited in a private house in Lincoln’s Inn Fields. Upon its demise, it was stuffed and afterwards acquired by the naturalist John Tradescant for his “cabinet of curiosities.” By the 1680s, the Dodo was extinct, and the Oxford Dodo was a unique museum specimen.

Eventually, Tradescant’s curiosities were integrated into the collection of the antiquarian, Rosicrucian and Freemason Elias Ashmole. This collection became the Ashmolean Museum and was donated to Oxford University. Preservation techniques of the time were not sophisticated, and by 1755 the specimen had deteriorated to such an extent that only the skull, beak and a foot along with some skin and feather samples were retained by the curators of the Ashmolean.

These remains of the Oxford Dodo—along with the iconic 1651 Flemish painting of the bird by Jan Savery—were transferred to the newly constructed Oxford University Museum of Natural History sometime after 1858. That new museum’s director and curator was none other than Sir Henry Acland, Oxford’s Regius Professor of Medicine and real-life model for the White Rabbit.

The Dodo: Extinct since the 1680s and Carroll’s favourite bird.

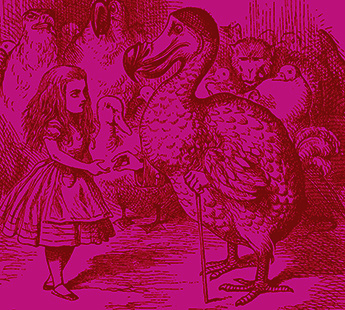

ZENO’S PARADOX On the philosophical level, the Dodo was the ancient Greek, ZENO OF ELEA (490–430 BC). Zeno’s most famous conundrum is known as the paradox of Achilles and the Tortoise. With absurd logic, this argument “proves” that Achilles (the world’s fastest man) can never overtake the tortoise, which has been given a modest head start in a race. When the tortoise has reached a given point, a, Achilles starts. But by the time Achilles reaches a, the tortoise has already moved on beyond to point b. And by the time Achilles reaches b, the tortoise has moved on to point c. Since this process continues on infinitely, Achilles can never overtake the tortoise.

Zeno’s argument is based on the assumption that you can infinitely divide space. It is both absurd and theoretically logical, so long as one does not take into account the factor of time. Mathematically, however, the resolution of the paradox had to await the discovery of calculus and the proof that infinite geometric series can converge.

In Wonderland, the Dodo gives instructions on how to run a Caucus-race. This is a send-up of the race of Achilles and the Tortoise that is even more absurd than Zeno’s race: it is a race with no rules and no fixed racetrack. It can begin or end whenever the participants wish, and when the Dodo calls time, all are declared winners and all are awarded prizes.

Zeno: The Greek philosopher still puzzles us with his paradoxes.

Zeno’s paradoxes were examples of a method of logical proof known as the reductio ad absurdum—meaning to reduce to the absurd—a method of refuting a premise by showing that it leads to an absurdity. This was known as the “destructive” method of argument and is employed by Carroll in absurd dialogues (to great comic effect) throughout Wonderland.

As an inventor of paradoxes himself, and a lover of the absurd, Carroll’s favourite philosopher was Zeno, and the Dodo was his favourite bird. Over the years, Carroll would construct scores of other paradoxes to puzzle logicians, but the best known today is an infinite-series reversal of Zeno’s most famous paradox.

Carroll’s paradox was entitled “What the Tortoise Said to Achilles” and has been seriously pondered by Bertrand Russell and several other twentieth-century philosophers. It is also the central focus of Douglas Hofstadter’s remarkable book Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid—A metaphorical fugue on minds and machines in the spirit of Lewis Carroll.

The transformation of Robinson Duckworth to the Duck is obvious enough, but that of Dodgson himself into the Dodo is a little more obscure. The Liddell children on a number of occasions visited the newly opened Oxford University Museum of Natural History, which at the time housed the only known relics of the famously extinct dodo of Mauritius. While in the museum, the Liddells would certainly have been shown the seventeenth-century Flemish painting of a dodo by Jan Savery, which was the model for Tenniel’s drawings of the Dodo in Wonderland.

The real reason for Dodgson’s becoming the Dodo could be revealed only through knowledge of a private self-mocking joke shared with the Liddell children. Though Dodgson suffered from a nervous stutter that made him a reluctant public speaker, he was seldom afflicted when in the relaxed company of children. Nonetheless, the Liddell girls would frequently have heard him nervously introduce himself on public occasions as Mr. Do-Do-Dodgson. And so we have the origin of the Dodo.

What’s more, the thirty-something Reverend Dodgson always tended to see himself as elderly (compared to six- to twelve-year-olds) and rather set in his ways, like the extinct bird. Furthermore, he certainly identified with the Wonderland Dodo with his walking stick who was the creator of original games. For indeed, Dodgson often carried a walking stick and delighted in inventing and organizing games for children.

The expedition that inspired “A Caucus-Race and a Long Tale” was not, as might be expected, the famous “golden afternoon” voyage to Godstow that is credited with inspiring Wonderland. Rather, it was a voyage taken a few weeks earlier to another favourite picnic spot: Nuneham Park, on the Harcourt family estate in the village of Nuneham Courtenay, Oxfordshire. There, Dodgson picnicked with his college friend Robinson Duckworth, the three Liddell sisters, two Dodgson sisters (Fanny and Elizabeth) and his aunt, Lucy Lutwidge. Caught in an unexpected downpour, the entire company was drenched with rain.

Dodgson recorded the voyage in his diary: “Expedition to Nuneham. Duckworth … and Ina, Alice and Edith came with us. We set out about 12½ and got to Nuneham about 2:15, dined there, and then walked in the park and set off for home about 4½. About a mile above Nuneham heavy rain came on, and after bearing it a short time I settled that we had better leave the boat and walk: 3 miles of this drenched us all pretty well. I went on first with the children … and took them to the only house I knew in Sandford … I left them … to get their clothes dried, and went off to find a vehicle … Duckworth and I walked on to Iffley, whence we sent them a fly. We all had tea in my rooms about 8½, after which I took the children home.”

In Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, not a great deal of evidence remains of the Nuneham picnic. However, in the original manuscript, instead of the Dodo’s proposal of a Caucus-race, a completely different passage appears that much more obviously draws on the real-life Nuneham outing:

A few pages later, Alice informs us: “if the Dodo hadn’t known the way to that nice little cottage, I don’t know when we should have got dry again.”

Scene of the expedition: A view of Nuneham Courtenay by William Turner of Oxford (1789–1862).

The differences between the Under Ground and the Wonderland versions at this point are peculiar. Why would Carroll switch finding a nearby house to a Caucus-race? A Caucus-race is a much less convincing way of getting dry, and certainly it is more confusing and less appealing to children. And what exactly is it? When no one can explain what a Caucus-race is, the Dodo simply states, “The best way to explain it is to do it.”

The truth is that with the insertion of this episode into the Wonderland version, Carroll has entirely changed the agenda. The Caucus-race is not there to entertain children; it is there as a parody of Christ Church politics. One result is a shifting of the real-life identities of the Mouse, Dinah the cat and Fury the dog.

Although not explained by the Dodo, caucus is a term for a committee of political fixers who try to avoid a competitive race between candidates by arranging to promote a single candidate (or a united political position for the party) before an election. Martin Gardner convincingly suggests that Carroll meant the Caucus-race to symbolize a committee that typically does “a lot of running around in circles, getting nowhere, with everybody wanting a political plum.” We certainly see this in the pointlessness of the race and the strange process and expectation of the prize-giving ceremony at the end of the race and the announcement that everybody wins!

The Dodo’s formal presentation to Alice of the “prize” of her own thimble is undoubtedly a reference to “thimblerigging,” or the “shell game,” a sleight-of-hand performed by Victorian fairground swindlers in which the victim is invited to bet on which of three shells a pea is hidden under.

In 1834, the expression entered the political arena when Lord Stanley gave his famous “Thimblerig speech,” an attack on the Whigs’ manipulation of Irish Church tithes and taxes. Thereafter, thimblerig came into common usage whenever a party or individual appeared to be manipulating or swindling the public. In Alice’s case, the Dodo is a metaphoric politician who taxes a member of the public, then makes a great show of presenting it back as a “gift” for which he must be thanked.

For over two millennia, the most respected and established source of information about metempsychosis and ideas concerned with the resurrection of souls was the Myth of Er, from Plato’s Republic. Er, the son of Armenios, dies in battle but revives days later on his funeral pyre and tells others of his journey into the afterlife. Carroll, of course, knew Plato’s Republic well, and as a clergyman and a classicist, he was most interested in this extremely influential account of the world beyond the grave.

In Plato’s Myth of Er, the behaviour of souls in the underworld is comparable to that of the creatures that emerge from the Pool of Tears. Many Victorians, like the ancient Greeks, believed in metempsychosis: the resurrection of the immortal soul in various human and animal forms.

Wonderland’s “queer-looking party” of birds and animals assembled around Alice might be compared to a scene in the Myth of Er in which—in Francis Cornford’s translation—“each company, as if they had come on a long journey, seemed glad to turn aside into the Meadow, where they encamped.… It was indeed, said Er, a sight worth seeing, how the souls severally chose their lives—a sight to move pity and laughter and astonishment; for the choice was mostly governed by the habits of their former life.… Souls in like manner passed from beasts into men and into one another, the unjust changing into the wild creatures, the just into the tame, in every sort of combination.”

Also in the Myth of Er, a high priest called the Interpreter takes charge and gathers all the creature-souls together. This is similar to the Dodo marshalling the Wonderland creatures in order to conduct a strange sort of race—perhaps emblematic of their previous life cycle (for each runs at his own pace and finishes whenever he wishes). And in the end, there are no losers, for everybody wins and all are allotted a prize.

Compare this to the scene in the Myth of Er: “The souls, as soon as they came, were required to go before Lachesis. An Interpreter first marshalled them in order; and then, having taken from the lap of Lachesis a number of lots…[said:] Souls of a day, here shall begin a new round of earthly life.… You shall choose your own destiny.”

As we have already seen in the prologue poem, Carroll has informed us of Alice’s identity as Secunda, the fatal sister also known as Lachesis the Measurer or “She who allots.” And this is confirmed as Alice allots the prizes in the form of comfits (candied fruits) “exactly one a-piece all round.” In the Myth of Er, the Interpreter “scattered the lots among them all” and “each took up the lot which fell at his feet.” And with these lottery tokens, each comes forward to choose its next life.

But what is this Mouse complaining about? It is only by identifying this much-aggrieved rodent that we can uncover the issues involved. Certainly, the meaning would have eluded Alice Liddell and her sisters, which is perhaps just as well, as the story essentially amounts to an attack on her father as dean of Christ Church and on his authority as head of the university.

The Mouse’s story is an allusion to the Aesop’s fable “Belling the Cat” (and likewise “The Mice in Council” by La Fontaine). Yet it is primarily meant as a political satire about the 1857 campaign by Christ Church students (lecturers and tutors) against the authority of the dean and the canons. The mice-and-cats metaphor for the students (mice) and the canons (cats) is a long-standing one: the Christ Church coat of arms displays four leopard faces, representing the canons of the college.

Carroll and other political pamphleteers at Christ Church often adapted the fable. Indeed, in a long poem in the pamphlet entitled “The Elections to the Hebdomadal Council” (1866), Carroll employs the fable as the basis for a continuation of the same long-running conservative student attempts to gain a place against the liberal reforms of Dean Liddell and his allies among the Canons. It reads:

“And here I must relate a little fable

I heard last Saturday at our high table:—

The cats, it seems, were masters of the house,

And held their own against the rat and mouse:

Of course the others couldn’t stand it long,

So held a caucus (not, in their case, wrong).”

In this chapter, the Mouse is no longer the Liddell family governess, Miss Mary Prickett, but THOMAS JONES PROUT (1823–1909), the tenacious leader of the conservative faculty and students against the near-absolute authority of the liberal dean and the canons. Charles Dodgson also took an active part in the campaign. And like the Dodo, Dodgson came to the aide of the Mouse Prout and held caucus meetings of rebellious conservative tutors (mice) in his college rooms.

“The Mice in Council,” illustrated by Gustave Doré.

Although there is no obvious connection between the Mary Prickett Mouse and the Thomas Prout Mouse, by coincidence Miss Prickett was born in the village of Binsey, just north of Oxford, and Thomas Prout was later the curate of that same town, which was home to St. Margaret’s Well, the “treacle-well” alluded to by the Dormouse at the Mad Hatter’s tea party.

After the Caucus-race and the allotting of prizes, Alice reminds the Mouse that he has promised to tell his story of why he hates “C and D.” All the creatures on the riverbank gather round, and the Mouse begins with what he describes will be “a long and a sad tale.” This leads to a typical Carrollian extended pun whereupon Alice looks down at the Mouse’s long tail and observes: “It is a long tail, certainly,…but why do you call it sad?”

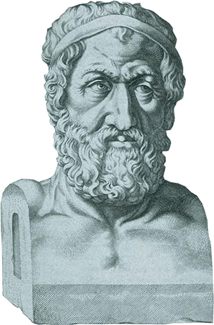

Thomas Jones Prout: This photograph was, of course, taken by his conservative ally.

The original “tale/tail” in Carroll’s handwriting.

With this pun, Alice combines the two homonyms and imaginatively creates the now famous Mouse’s tale of a tail. This figured, or chirographic, poem is printed in a way that visually conveys its subject. Once again, the original Under Ground manuscript employs, in handwritten form, the same visual tale/tail idea and structure. However, it is a different poem entirely. In Alice’s Adventures Under Ground, Alice’s “idea of the tale was something like this:”

This original Under Ground tale/tail poem is more appropriate for a child reader as it attempts to give an explanation for the Mouse’s hatred of C and D that would make sense to a child. The Wonderland version explains only D: a vengeful dog named Fury “in the house” (Christ Church was always referred to as “The House” by its residents) who obscurely threatens to take legal action against the Mouse in a rigged court. It makes no mention of the cat. The story is never completed, and Alice manages to offend the Mouse and all the other birds and animals by injudiciously reintroducing stories about her affection for Dinah the cat (and Fury the dog).

Arthur Stanley: The cat was a liberal canon.

The C, or cats, the Mouse hates are the canons of Christ Church, and the D, or dog, is the dean (and Alice Liddell’s father), HENRY GEORGE LIDDELL (1811–1898). The cat most feared by the mice appears to be Dinah. Dinah was the name of the real Deanery cat belonging to the Liddell sisters, but the fictional creature is also a reference to the dean’s closest friend and confidant, ARTHUR PENRHYN STANLEY (1815–1881).

Stanley was a liberal canon of Christ Church and a frequent target of Carroll’s satirical squibs. He had been secretary to the 1851 royal commission of inquiry into the state of education at Oxford and Cambridge, and gave the impetus to all the liberal educational reforms that the heavily conservative faculty of Christ Church so strenuously wished to resist.

Educated at the Rugby School, and later its master, Stanley was widely believed to be the model for George Arthur in Thomas Hughes’s novel Tom Brown’s School Days (1857). A leading liberal theologian of his time, Stanley married the sister of Lord Elgin, then viceroy of India (and earlier governor general of Canada). He was a royal favourite and was chosen to accompany the Prince of Wales on his tour of the Middle East. He eventually became dean of Westminster Abbey and delivered sermons at the funerals of Thomas Carlyle and Benjamin Disraeli.

Like the dog in the Mouse’s tale, the dean—with the help of Stanley and the other canons—was initially able to suppress the tutors’ revolt and maintain authority. However, the tenacious Prout fought on, and nearly a decade later, through an alliance with the undergraduates, finally succeeded in winning more power for the predominantly conservative faculty and thereby slowing the pace of the Dean’s liberal agenda at the university. Thomas Prout came to be known as “the man who slew the canons.”

However, Prout the Mouse and Dodgson the Dodo proved to be among the last to gain life-long residency in “The House” through the old system of ecclesiastic privilege and favour. Under that system, no teaching or compulsory academic requirement was attached to the guarantee of a life-long salary with free college apartments, board and common-room membership. Dodgson was in residence for forty-seven years, while Prout the Mouse—despite the efforts of the dog—remained ensconced in a comfortable residency for sixty-seven years, “warm & snug & fat—Think of that!”