Chapter 1

Sarah Stevens would pick truth. I knew she would.

I mean, yeah, sure, there was an outside chance she would pick dare. But since the dares on this particular day were limited by (A) the confines of a fifteen-passenger van and (B) the moral authority of its driver, there wasn’t a lot of point to picking dare.

Now, generally when you play truth or dare in eighth grade, all the dares end up being some sort of expedition to explore the anatomy of the opposite gender. I dare you to put your hand here or your lips there. But not so much when you’re with your church youth group, and not so much when your youth group pastor, Joe Slater, is driving, and it just so happens that he recently took the youth group to a weekend-long seminar called “I Kissed Dating Good-bye,” where you learned that you should save physical exploration, including all forms of putting your hand here or your lips there, for marriage.

So in this particular church-van environment, picking dare was pointless. If you did, you would end up with something lame, gross, and improvised, like eating a leftover fast-food squeeze packet of mayonnaise or whatever.

Tony had picked truth, and then he was asked who he liked, which turned out to be some girl from his Christian school who most of us didn’t know. It was kind of a letdown, but now his turn was over, and he had picked Sarah Stevens.

“Sarah, truth or dare?”

As long as she picked truth, I knew with complete certainty what he would ask her. Tony had my back.

“Truth.”

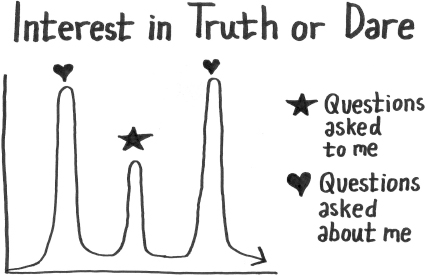

Tony looked at me. We shared a slight nod. We knew what was about to go down. This was it. The Big Moment. Our chance to see if our theories were correct, if Sarah Stevens liked me the way I liked her. If she had been talking with her best friend about me the way I had been talking with Tony about her.

“Do you like Josh?” Tony asked.

Check.

Obviously, I couldn’t ask her myself, even in a game of truth or dare, because that would be awkward. But I knew Tony would do it for me. I mean, he stuck with me even when I had cancer. And that’s about as serious a test a friendship can face.

We had grown up two doors away from each other, Tony and me. I’d always been homeschooled and he’d always gone to Christian school, so I would spend my days waiting until he got home, when he could come outside and build forts with me.

Then: the cancer.

I was nine. I had a 50 percent chance to live. I would go to the hospital for five days, then come home for two weeks, then go back to the hospital. When I was home, I had hardly any energy. I didn’t play outside. And I couldn’t build forts or ride bikes or do any of the things Tony and I used to do, before I got sick, and before my left leg had to be amputated from the hip down. But you know what? Tony didn’t care. He would sit inside with me and play computer games or board games or whatever it was that I had the energy to do. That long year of chemotherapy, that’s when I first learned that Tony had my back.

Everyone at Covenant Presbyterian Church did, really. Even Sarah Stevens, come to think of it. She had been one of fifty kids who bought “Covenant Kids for Joshua” T-shirts. And when I first started losing my hair to the chemotherapy, Sarah’s little brother, Jim, had been one of eighteen boys who gathered in my family’s backyard one afternoon and shaved their heads. That’s the thing about going to church. There’s a bunch of extra rules you have to follow—like about dating—but the upside is that if you get cancer, if your life falls apart, church people will shave their heads and buy T-shirts for you. They will do anything they can to help you.

Sarah Stevens glanced at a couple of the girls in the van. They smiled, biting lower lips to suppress giggles. For a moment, I basked in the hope that this meant she was going to say yes.

“No,” she said, looking at Tony, not at me.

I felt a hot, tingly sensation spread over my skin as I slid down a few inches against the bench seat, wishing I could just melt directly into its crusty upholstery. Not only did Sarah Stevens not like me, but she had just said so in front of all fifteen passengers in this van. It was a one-two knockout punch of rejection plus humiliation.

I disengaged from the truth or dare game until its chatter was mere background noise. After you’ve been shut down in front of everyone, publicly declared to be uncrushworthy by Sarah Stevens, who cares about anything else? So what if someone is gagging on a squeeze packet of mayonnaise?

At the retreat center, I set a pair of crutches on the unfinished cement floor, beneath the bunk bed I was sharing with Tony. We were staying in a rustic cabin with twenty bunk beds and a single naked lightbulb operated by a hanging string of tiny metal balls. I navigated my way through the maze of bunks to Joe Slater, who was unrolling his sleeping bag on the plastic mattress of a bottom bunk. Joe was in his late twenties, with an intense gaze, a booming laugh, and a V-shaped athletic build, all of which perfectly matched both his name (Joe Slater!) and his job description (youth pastor!).

“Hey, Joe, what are we going to do next?”

For me, not knowing the activity schedule was like living in an environment where the weather could fluctuate by one hundred degrees at any moment: I never knew what to wear.

“We’re going to dinner,” he said. “In the dining hall.”

Dinner. Got it. Keep the prosthesis on.

Since my leg is amputated all the way up at my hip, my prosthesis includes three artificial joints: hip, knee, and ankle. Which makes the leg very heavy and cumbersome to wear.

There are a lot of amputees who run and play sports with their prostheses on. These tend to be the amputees who are popularized in the media and thus the sort who come to mind when the average person thinks of the word “amputee.” But most of these amputee-athletes are below-knee amputees, meaning their legs end somewhere between the ankle and the knee. If you are a below-knee amputee, particularly if you are missing only your foot, a prosthesis can allow you to run just as fast as an able-bodied person. Above-knee amputees, though, have a harder time, because they don’t have the muscles of the quadriceps to propel their knees forward. It is possible to run with an above-knee prosthesis, but it is difficult and certainly not as fast as running with a real human leg. Most difficult of all, though, is the hip-disarticulation level, which is what I am. For hip disartics, running on the prosthesis is not possible. The leg simply doesn’t swing through fast enough.

So for most types of athletic activities, I would take my leg off and either run with my crutches, or set my crutches down and hop. I was faster and more agile without the leg. But I was also more self-conscious, and with the crutches, I didn’t have my hands free to, say, carry a plate of food. Which is why I would wear my leg to the dining hall for dinner, and why I planned to wear it to all nonathletic social activities during the retreat.

After dinner, Joe got up and gave the rules for the weekend. The usual—no going into the other gender’s cabin, no talking after lights-out, no going off anywhere by yourself. Stuff like that. Then Joe told us to open our Bibles, and he gave a “talk,” which is youth-group-speak for a sermon. The usual—no getting distracted by worldly pursuits, no motives except to bring glory to God, no sexual or impure thoughts. Stuff like that.

He prayed and then announced that we were all meeting by the lake in ten minutes. Prosthesis still on, I walked over to Joe.

“What are we going to do next?” I asked.

Joe frowned, not wanting to ruin the surprise.

“By the lake?” I persisted.

“Don’t tell anyone… but it’s nighttime capture the flag.”

“Cool, thanks.”

That meant leg off, using crutches, so I would be able to run. Of course, even with my crutches, I wasn’t an especially useful teammate in capture the flag—I couldn’t really hold the flag and move at the same time. But at least on the crutches I could run around to make it look like I was participating. The participation would be fake, but what did that matter when the alternative was wearing, you know, a fake leg? That’s what it means to be an amputee: You’re always putting on a show.

Down by the lake, we divided into teams, counting off by ones and twos. I tried to shift in line so I could be on the same team as Sarah Stevens. It worked. Not that I was going to talk to her or anything, not after her bombshell during truth or dare, but for some reason it seemed important that we be on the same team, working together to capture the same flag.