Chapter 8

A few days after I had to miss homecoming, I was standing outside at the end of the school day, waiting for Mom to pick me up, when I was approached by a college-aged guy wearing a trucker hat and cowboy shirt.

“What’s up, bro?” he said, offering a fist bump. “What’s your name?”

“I’m Josh.”

“Word. They call me Miller.”

“Nice to meet you.”

“So listen, you should come out to club tonight.” He handed me a photocopied flier. “It’s gonna be mad fun.”

“Cool, thanks.”

He walked away to find his next target. I examined the flier. It was a hand-drawn map to someone’s house that read YOUNG LIFE CLUB, 7 PM.

My mind pinged, alerting me to a connection between this flier and Liza Taylor Smith. What was the connection? I thought for a second. Oh yeah, her note! She had said she heard about me from her Young Life leader. Bingo. My chance to finally meet Liza Taylor had literally just been handed to me.

I’d never been to Young Life, but I’d heard of it. It was a Christian organization, sort of a youth group for public schools, led by local college students and other volunteers. The religious affiliation made it an easy sell to Mom and Dad.

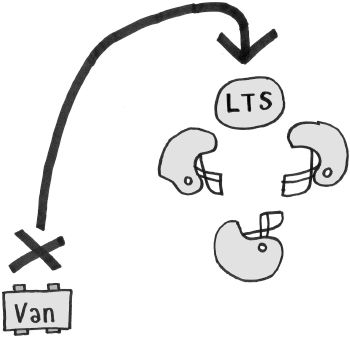

That night, Dad dropped me off at the address on Miller’s map. I got out of the van and spotted Liza Taylor almost instantly. As promised, she was holding court with a circle of guys, all upperclassmen, all football players.

I didn’t want to interrupt, so instead of butting into the circle, I perched politely just behind Liza Taylor and waited to see if she would notice me.

I guess she eventually felt my breath on her neck or something, and she turned around to face me. I didn’t say anything, just waited for her to place me.

“You’re Josh Sundquist!”

“Yup!”

“I’m Liza Taylor!”

“I know,” I said.

“This is so cool! I didn’t know you came to Young Life!”

“It’s my first time.”

“Well, I’m so glad you’re here!”

Then, silence.

We were nearing the point at which a conversational pause turns into awkwardness when the door to the basement burst open and Miller stepped out.

“Everyone inside!” he bellowed.

“Okay, maybe I’ll talk to you after club?” Liza Taylor offered.

“Yeah, okay, cool,” I concurred.

Everyone funneled through the door into the basement. The furniture had been cleared out to provide ample floor seating. Everyone was gathering on the carpet with their groups of friends. Not having a crew of my own, I sat alone behind the farthest row in the back of the room. There’s a big difference between knowing everyone’s name and having a group of friends that counts you as one of its members.

Sitting on the floor with a prosthesis like mine is a little awkward. The hip joint doesn’t rotate in, so you can’t sit cross-legged as most people would in a crowded situation like this. You have to sort of recline, legs out in front of you, palms planted behind you. So you take up a conspicuous amount of floor space, which is especially annoying when you want to be invisible so no one notices that you are sitting by yourself.

Miller jumped up in front of the room.

“What’s up, club?” he screamed, drawing wild applause. He high-fived a few people in the front row.

“I thought we’d start off tonight with a little… competition!”

The promise of competition elicited another round of cheering.

“In honor of the fall holiday known as Thanksgiving, a.k.a. Turkey Day, we are going to have a pumpkin race!”

Although I wasn’t sure what a pumpkin race was, just the word “race” gave me an instant flashback to my childhood. When I was seven, I won a blue ribbon in the homeschool science fair for an experiment in which I proved that sprinting at my top speed (which the judges agreed, based on the data I had recorded, was indeed very fast) increased my heart rate compared to when I was walking. I loved to run races back when I had two legs.

“Here’s how it works. In a minute we’re gonna go back outside, and three competitors will line up at the starting line. They will run out and around the big tree in the front yard. First one across the finish line wins. Oh yeah—and they will be wearing one of these on each foot!”

He produced a pumpkin from the floor in front of him and held it aloft with one hand. The crowd went crazy. Holding the stem of the pumpkin with his other hand, he lifted off a circular top section that had been precut from the pumpkin and showed us the orangey innards through the hole.

“You just take your shoe and sock off and then”—he dropped the pumpkin stem and plunged that hand into the pumpkin—“put your foot right up in there!” He removed his hand to show that it was covered up to his forearm with pumpkin seeds and bright orange strings of pumpkin guts. An eww-that’s-so-gross laugh erupted in the basement. He set the pumpkin down.

“Now, tonight before club started, three people came up to me and they were like, ‘Miller, can I please be in tonight’s competition!’” This drew a knowing laugh. He pulled a slip of paper out of his pocket. As he read each name, there was a smattering of applause.

“… and Josh Sundquist!”

Liza Taylor, who was sitting in the front, was one of the first to turn around and look at me. She smiled. I felt heat rising to my face.

I wondered how Miller knew my last name. Maybe he had gotten it from Liza Taylor. Or maybe from Liza Taylor’s Bible study leader.

But it didn’t really matter how he had found out, because he had—that was over and done with—and now I had to deal with this impossibly uncomfortable situation. Other than Liza Taylor, none of my classmates knew I was missing a leg. If they had known, they would not be clapping; they would be wondering, as I was now, whether it was possible to do this competition with a prosthesis on.

I considered it: I could take the shoe off my artificial leg, though doing so was quite difficult and usually required two hands or the use of a shoehorn. But even if I did get my shoe off, my ankle did not have enough forward flexion to fit through that hole in the top of the pumpkin. In the end, though, none of that mattered, because I simply couldn’t run with my prosthesis, pumpkin shoe or not, because the artificial leg didn’t swing through fast enough.

I sat still by myself on the floor while everyone made their way outside for the race. I was about to break both my rules: I was going to be a burden on Miller by telling him I couldn’t compete, and I was going to identify myself as different when everyone started to wonder why I had dropped out.

Outside, the other two competitors were already clad in their pumpkin footwear. I shuffled over to Miller.

“You ready to gourd up, bro?” he asked.

“Yeah, that’s what I need to talk to you about,” I said. I leaned my head toward the street, indicating we should turn to face away from the group. “I can’t do it. I, um… I have… I have an artificial leg.” I glanced down at my leg, which was covered with a pair of pants.

“Oh, bro, I’m so sorry,” said Miller. He did indeed look really sorry, though not so much sympathetic sorry as what-have-I-done horrified sorry.

“It’s all right. I lost it a long time ago.”

“No, I’m sorry about calling you up for this race. I had no idea.”

“It’s cool. Sorry I can’t, you know, compete.”

“If you want, you can be in another one of tonight’s skits. Next we’re doing a competition where you put panty hose over your head and have to eat a can of pumpkin pie filling through it—can you do that?”

Can I eat pumpkin pie? This was why I didn’t like for people to know I had a fake leg. Once they did, they assumed I wasn’t able to do much of anything.

“Sure.”

I looked back at the other students, all of whom were monitoring my conversation with Miller. Had they figured out my secret? I searched for Liza Taylor Smith’s face in the crowd, but I couldn’t find it.

After that night, I saw her on occasion at school. But everything had changed; it had become impossible to believe she could be interested in me, even in my most optimistic of daydreams. During our brief conversations in the hall at school, as I tried to maintain eye contact, fighting the visual gravity of her perfect body, I was distracted by my assumption that she was distracted. I was sure she must be replaying her memory of the Young Life meeting, thinking about how I couldn’t participate in the pumpkin relay because my own body was irrevocably broken.