Chapter 13

It was a month into the summer, and I had been coming over to Francesca’s house once or twice a week to play pool in her basement. After I beat her,4 we’d sit on the porch swing in the backyard and talk. Or I’d take her to Jess’s Quick Lunch downtown. All of which is to say, by the time we went hiking we were pretty skilled at talking to each other, which was good since the drive to the trailhead was longer than I remembered—about two hours, or two and a half Ani DiFranco CDs.

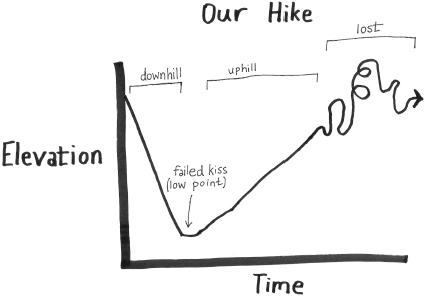

Hiking down to the base of the falls is pretty easy because you’re doing just that. Hiking down. You park on Skyline Drive in Shenandoah National Park and then you descend for four miles of switchbacks, worrying the whole time about the moment when you will be sitting on that rock overlooking the waterfall and you will turn your head sideways and purse your lips and close your eyes and move in for the kill. But if you close your eyes first, how will you know where, exactly, to move? Maybe you move in first and then close your eyes? And when do you insert your tongue into her mouth?

The base of the falls was just how I remembered it from when I went there with my youth group in eighth grade, when I climbed on top of that rock and that guy told me to bring a girl back here someday: heavily wooded with trees and shrubbery and shadowed by a towering rock face, with a backyard-pool-sized swimming hole underneath. There was no one else there. It was like our own perfect, private oasis in the forest.

I had been hoping that Francesca would wear a bikini that day, but she was sporting a modest green-and-black one-piece.

Much more disappointing was that she wouldn’t swim in the pool underneath the falls.

“It’s too cold,” she said.

She just stood up to her ankles and watched while I jumped off a low ledge into the water, trying to splash her with irresistible fun vibes. But she didn’t budge. She just smiled and said something about how this all looked like a movie, which made me realize that if this were really a movie, my character would be expected to grab her around the waist and pull her into the water. She would shriek and scream in protest, but deep down she would love it. Then we’d splash each other and giggle like schoolchildren, and she’d start trying to dunk me, and then I would fake like I had drowned by breathing through a straw made out of bamboo, and she’d freak out and start crying and her wrists would hang limp while she flapped her hands, and then I’d pop out of the water and surprise her and she’d laugh and then we’d kiss. And maybe that’s what she was hoping would happen. After all, why else would she strip down to her swimsuit and stand at the edge of the water like that? I started to swim toward her so I could pull her in, but while I did so I made the mistake of thinking. Then I stopped and treaded water. I couldn’t do it. There was simply too much risk. Risk that she’d be annoyed by the cold water. Risk that she would find me grabbing her around the waist inappropriate. Risk that my balance, standing with one leg on the slick rocks, wouldn’t be stable enough to topple her. Risk that it would be awkward. Risk that she didn’t like me. I shook my head, wishing I were in a movie instead of in my brain.

“What?” she asked.

“Nothing.”

I climbed out of the water and picked up my crutches. I thought about putting my shirt back on but decided to keep it off in the hope she would be impressed by what I imagined were the chiseled muscles of my sixteen-year-old chest. This, I would soon discover, was a massive tactical error. But not for the reasons you probably think.

“Come on, I want to show you something.”

We walked in our swimsuits and bare feet up the steep, rooted path. At the top, we came to the rock, and again I hesitated—not about kissing her, but about simply sitting down. What if I sat down and she didn’t sit beside me? I looked at her. I looked at the rock. No, couldn’t do it. Too big a risk. So I just stood there surveying the stupid trees below and thinking how stupid it was that I couldn’t even bring myself to take the risk of sitting on a stupid rock and what was wrong with my stupid brain, until suddenly she sat down on the rock and looked up at me like I was supposed to join her. I smiled and bit my lower lip.

“What?” she asked.

“Nothing.”

I set my crutches down and then sat beside her, beads of water rolling down my back. Phase one was complete.

But I wasn’t sure how to initiate phase two, the kiss. Maybe I could do so by telling the story of how I first came here three years ago, how ever since then I had thought this would be a perfect place for, you know, a first kiss?

“I came to this rock a few years ago. I’ve always wanted to come back.” Upon its telling, I realized the story was both shorter and less effective than I had hoped.

“It’s a beautiful view,” she offered.

“Yeah.”

We were silent for a while, listening to the roar of the waterfall. It was the good kind of silent, though. She breathed in slowly through her nose, taking in the scene. And then she said, thoughtfully, “It smells like pot up here.”

I had absolutely no clue what pot smelled like.

“Yeah,” I said, sniffing. “It totally does.”

Then we were quiet again.

I decided to try another tactic for initiating phase two, the Deep Conversation.

“Let me ask you something,” I said.

“Okay.”

“Why do you think adults give up on their dreams?”

“Um, I don’t know.”

“But you know what I’m saying, right? It’s like everyone our age wants to change the world or be famous or something, right?”

She shrugged. “Yeah, I guess.”

“But most adults don’t do any of those things. They just live sort of normal lives. But it’s like, they’re okay with that. It doesn’t bother them.”

“I never really thought about it that way.”

“Why do you think that is?”

She was quiet for a little bit. “I don’t know. I guess people just get busy.”

“I guess so.”

“What do you think?” she asked.

I didn’t know. But I wanted to know. I wanted my life to count. I wanted my dreams to come true. “Yeah, you’re probably right. People get busy.”

I looked out at the treetops and continued speaking with all the heady profundity that comes with knowing so much and understanding so deeply how the world works. “They get busy with being married and having children and house payments. And then they’re old and they missed out on their dreams.”

“That’s probably it.”

“Good thing we’re still young.”

“Yeah.”

“And that we figured that out.”

“Yeah.”

We were both watching the water zip off the edge just below us. You could taste the mist coming off the falls.

“I want to change the world,” I blurted out.

“You do?”

“Yeah. And I’m going to do it, too.”

“How?”

“I don’t know. But I’m going to.”

She looked right in my eyes.

“I believe you,” she said, seriously.

We held each other’s gaze. Neither of us said anything. Neither of us moved. Neither of us even blinked. I moved my head forward exactly one centimeter. She squinted slightly, questioningly.

This is it, I thought. It’s going to happen. My first kiss. Right now.

That’s when it hit me: I was wearing a swimsuit. No underwear. No shirt. If I got, you know, excited, which seemed all but certain during my first kiss, it would be about as subtle as a circus tent going up on your next-door neighbor’s front lawn. And what would she think? Would she be grossed out and go home and call her friends and tell them about it? Would it be a story that followed me through the halls of my high school until graduation?

“Well, it’s getting kind of late,” I said, glancing up at the dimming afternoon sky.

Her body jumped involuntarily, as if startled.

“Oh. I guess you’re… right.”

As we hiked all the way back up to the car, I told her about my dream to become a Paralympic ski racer someday. I had learned to ski right after I lost my leg as a kid, and while I was still on chemotherapy I met a former coach of the US Paralympic Team, who told me I had “great potential.” Ever since then, ever since that day, I had wanted to race in the Paralympics. I asked her what her dreams were, and she said she didn’t have any. I told her she should get some.5

“I guess you’re right,” said Francesca.

Hiking against gravity was significantly slower than hiking with it, as it turned out. The sun set and the trail turned dark under the canopy of a dense pine forest. Interesting, I thought, since we hadn’t walked through any dense pine forests on the way down.

“I think we lost the trail,” I said.

We examined the bed of pine needles under our feet. There was indeed no trail.

“This is like something out of a horror movie,” she said.

I recognized this as my cue to demonstrate bravery.

“Yeah, pretty freaky,” I agreed, not bravely at all.

Francesca and I wandered around the woods in the dark, trying to navigate by moonlight and the North Star, something I had learned how to do in Boy Scouts. By “learned” I don’t mean I could actually do it, but that I knew enough big words (“latitude,” “equator,” “compass,” “south by southwest,” etc.) to get the orienteering merit badge.6 So my only real strategy was to keep us walking in the same direction. As long as you go in a straight line, you’ll eventually run into the end of the national park, right?

I would later discover that as we wandered, Francesca’s dad was calling my house every hour. At one point Francesca’s dad said to my dad on the phone, “I just want you to know, even though I’m a little worried right now, there’s actually no young man I’d rather have my daughter out with than your son.”

Oh, great. Thanks. Just what every teenaged Ani DiFranco fan wants, a guy who has the enthusiastic endorsement of her father.

I’m not sure why parents always liked me when I was growing up. Maybe because I used big words and knew how to do math problems. Maybe they thought cancer made me mature for my age. Maybe because they thought I wouldn’t be able to try anything on their daughters since I had a physical disability. Whatever it was, it’s safe to say that if girls chose their boyfriends based on who their parents liked, I could’ve required resumes and head shots from girls before they would even be eligible for consideration. That’s how much the parents liked me. But parental approval doesn’t do much for you when you’re trying to date high school chicks. In fact, it makes it harder, because deep down every teenaged girl wants to bring home some biker dude with prison tattoos and a tendency to break anything that shatters (beer bottles, windshields, young girls’ hearts) just so her dad will flip out.

Eventually, Francesca and I stumbled out of the pine forest onto a road. There were no cars or people in sight.

“This really is just like a horror movie,” she said again.

Being that in my family we weren’t allowed to watch PG-13-rated movies until we were sixteen, and R-rated movies until we were adults and responsible for our own souls, I had never actually seen a horror movie.

“Yeah,” I said. “It totally is.”

We followed the pavement in a randomly chosen direction for thirty minutes and eventually found the parking lot, empty except for my car, which was sparkling in the moonlight thanks to a trip to the car wash that morning.