Jura, Craighouse

Overview map

Islay

You can almost catch the smell of the angels’ share on Islay’s sea breezes. This island – even more than Speyside – is regarded as the spiritual home of Scotch whisky, and the names of its distilleries are famed worldwide for their rich, peaty malts. But there’s much more to the island than the water of life. Islay is known as the ‘Queen of the Hebrides’ and is blessed with picturesque whitewashed villages, unique birdlife, fine sandy beaches and a rugged coastline worthy of exploration.

Islay is well served by large CalMac vehicle ferries from Kennacraig on the Kintyre peninsula. These sail two or three times a day, landing at either the village of Port Ellen in the south (2 hours 10 mins), or tiny Port Askaig (2 hours 5 mins) overlooking Jura, and most have connecting bus links from Glasgow. In the summer there’s also a weekly ferry from Oban, via Colonsay. Islay has an airport at Glenegedale, served by three daily flights from Glasgow in the summer and two in the winter, as well as a twice-a-week day return service from Oban and Colonsay.

The island has a wide range of accommodation, shops and places to eat, and all the main villages are linked by bus.

Discover the water of life

With nine working distilleries, many in picturesque seaside locations, Islay is simply the place to sample a dram. Laphroaig, Lagavulin and Ardbeg distilleries on the south coast are the island’s most famous and heavily peated. It’s fascinating to see behind the scenes, inhale the heady brewery scent from the giant vats of bubbling wort and check out the vast quantities of whisky maturing for years in the bonded warehouses. It’s also a great way to warm up on a dreich and rainy day. The distilleries offer standard tours and tastings of their main single malts, but also more specialist tours designed to appeal to the real connoisseur. These are often in intimate small groups with the opportunity to sample some of their rarer expressions. Laphroaig, Lagavulin and Ardbeg can all be visited on foot or by bike on a dedicated six-kilometre path from Port Ellen, although it’s best to book the actual tours in advance. Ardbeg – the last of the three – has a very fine cafe, and you can even return to Port Ellen by bus if you’re feeling a little wobbly at the end of your adventures in malt.

Get twitching

Islay is a heaven for birdwatchers, renowned for the chance to see rare species like the chough and the corncrake, and for the many thousands of overwintering geese who migrate from the Arctic to munch on Islay’s verdant grass. Head to the RSPB centre at Loch Gruinart to visit hides overlooking the loch and check the recent sightings – during the winter months a dawn or dusk visit can be spectacular as the geese arrive or depart to and from their favourite grazing spots. Spring brings masses of migrating birds including plenty of rare oddities blown off course and taking shelter on the island for a short while. The coastal cliffs support a wide variety of seabirds including nesting puffins on the Oa peninsula – also a good place to look out for golden eagles and hen harriers.

Pay your respects to the Lords of the Isles

Islay has an important place in the history of Scotland’s islands, and there are a several sites in stunningly scenic locations which no visitor can afford to miss. First stop for history buffs should be Finlaggan, a few kilometres from Port Askaig. On an island on a loch here lived the Lords of the Isles who ruled a large kingdom across the west of Scotland from the thirteenth to the fifteenth centuries. Today you can walk across a boardwalk to visit the site and see the remains of a castle and chapel, together with some very fine carved sixteenth-century gravestones and numerous archaeological artefacts.

Islay, Ardbeg distillery

Islay, Soldier’s Rock

Islay, Portnahaven

Islay, on Beinn Bheigier

Islay, Machir Bay

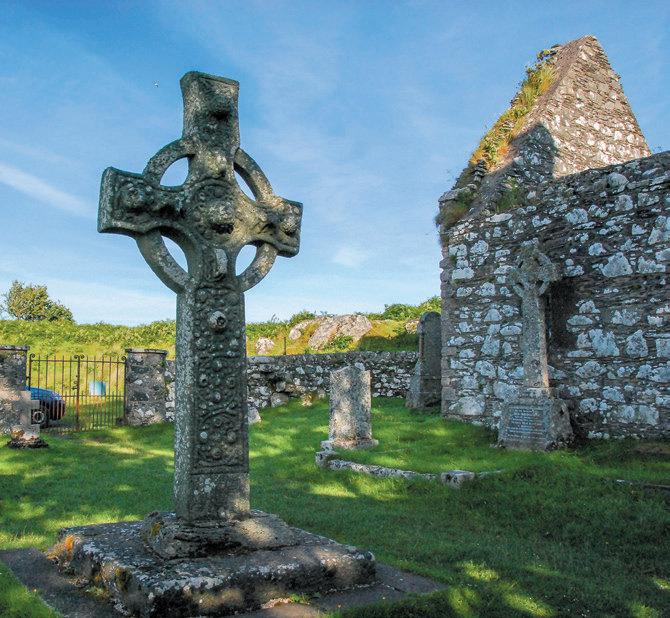

Islay, Kildalton Cross

Islay, Bowmore round church

Visit Bowmore’s round church

This striking circular building dominates Bowmore from its position at the top of the Main Street. It was built in the 1760s, and its roof is supported by a massive central oak pillar and walls that are almost a metre thick.

See Kildalton Cross

This ancient carved cross in the remote graveyard of Kildalton Church is regarded as the finest surviving example of early Celtic Christian carving. Dating from AD 800, it features the classic spiral and knot work around two roundels, Christ as a lion, the Virgin and Child, and scenes including Cain killing Abel, the sacrifice of Isaac, and David slaying a lion. There’s another very fine cross at Kilchoman on the Rinns peninsula.

Machir Bay and Kilchoman

Islay has some superb beaches, including Laggan Bay which stretches for over seven kilometres along the east coast. The finest, however, is Machir Bay on the Rinns peninsula – a perfect expanse of golden sand backed by dunes and just a short walk from a car park. Before leaving, be sure to visit the nearby Kilchoman distillery. Opened in only 2005, this was the first new distillery on Islay for 124 years, but its traditional methods are a contrast to the mass production of its big-name rivals. It uses barley grown on its own farm, and is one of only six distilleries in Scotland to still carry out all its own traditional floor maltings. Non-whisky buffs will enjoy the cafe which serves the finest Victoria sponge cake you can imagine.

Mull of Oa

The Oa peninsula is Islay at its most rugged, a wild moorland fringed with fine sea cliffs. Its final headland – the Mull of Oa – is the site of the dramatic American Monument, perched 130 metres above the waves. Towards the end of the First World War, a massive troop ship carrying over 2,000 US soldiers was torpedoed off the Oa. Although other boats in the convoy quickly began a rescue mission, many men drowned and in some cases lifeboats were dashed against the high cliffs. The stories of locals rescuing survivors and providing dignified burials for many of the lost are very poignant and can be explored at the fascinating Museum of Islay Life in Port Charlotte. The American Monument commemorates both this disaster and the shipwreck of the HMS Otranto in 1918 with the loss of over 350 souls. There’s a waymarked three-kilometre circular walk out to the Mull from the car park at the end of the road.

Bag the Beinn

At 491 metres high, Beinn Bheigier doesn’t rival the great Paps on neighbouring Jura, however as the highest point on Islay it does command fabulous views; the summit can usually be enjoyed in splendid solitude as the hike up involves tough, pathless terrain that deters many. The usual start point is the end of the road at Claggain Bay on the east coast. An often sodden path can be followed via Ardtalla to the empty cottage at Proaig, from where a stiff walk through deep heather leads up to the summit. If you fancy walking company, the island hosts an annual festival in April that usually takes in guided walks on Colonsay and Jura as well.

Fèis Ìle

Islay’s annual ‘music and malt festival’ is held at the end of May and combines a varied programme of tunes, songs, history, piping, Gaelic workshops, and just the occasional dram at special distillery open days, as well as friendly ceilidhs and food-themed events. For those seeking an even more laid-back vibe there’s an annual jazz festival too – held in September, it’s also sponsored by a whisky producer.

www.islayfestival.com

Islay Book Festival

Held every September, the Islay Book Festival has a varied literary programme, often featuring books with a connection to the water of life, of course.

www.islaybookfestival.co.uk

Beach rugby tournament

Each June, over a thousand spectators watch thirty teams of both sexes battling it out on a pitch set up on Port Ellen’s sandy seafront.

Ride of the Falling Rain

Taking place in August (which has surprisingly high rainfall figures) this very informal 162-kilometre cycle ride around the island stops midway at Ardbeg distillery and raises funds for World Bicycle Relief, which does what it says on the tin.

Jura

‘Why does it take longer to get to Jura than it does to get to Peru?’, the labels on Jura’s whisky bottles used to ask, answering, ‘it just does’ – giving something of a flavour of the character of this large and largely empty island. Separated by only a narrow sound from Islay, Jura contrasts starkly with its neighbour in the way only Hebridean islands can. The population of only around 200 is strung along the forty-odd kilometres of its eastern coastline, and is vastly outnumbered by the 6,000 red deer which keep the interior of the island a rugged, tree-free moorland.

Jura, Beinn an Oir – highest of the Paps

Jura, otter

The usual access to Jura is a short hop on the tiny car ferry that plies to and fro across the sound from Port Askaig on Islay – itself a couple of hours’ ferry journey from Kennacraig on the Kintyre peninsula. The ferry lands at Feolin, at the southern end of Jura’s road that links most of the eastern coast. During the summer months there is also a fast RIB that operates a passenger-only service from Tayvallich; this takes an hour and lands at Craighouse, Jura’s main settlement. Here you’ll find Jura’s shop, cafe, hotel and distillery; there’s also a bed and breakfast and a few holiday cottages.

Climb the Paps

Jura is dominated by three great cones of quartzite scree that rise like pyramids from the moor – the awe-inspiring Paps. The lack of paths and extreme steepness and ruggedness make the round of all three Paps one of the most challenging of Scotland’s classic big hillwalks. The highest, Beinn an Oir (‘the golden mountain’), is actually the easiest to climb, and can be done on its own. Starting from the bridge over the Corran River, wet and indistinct paths lead over the bogs to eventually cross the outflow of Loch an t-Siob. The route to Beinn an Oir then passes the north side of the loch before climbing to the bealach (or pass) between Beinn an Oir and its neighbour, Beinn Shiantaidh. From here a rising terrace heads up across the eastern side of the mountain before a final walk over angular quartzite stones leads up to the summit – an incredible viewpoint. The easiest return is to retrace your steps.

The full round of the Paps is only for the toughest of hill gangrels; for this, the route is the same as for Beinn an Oir as far as the outflow of Loch an t-Siob, but from there head north to reach the south-east ridge of Beinn Shiantaidh – and then embark on a gruelling battle with loose shifting screes to the summit. The descent of the west ridge also requires care before the terrace described above is used for the ascent of Beinn an Oir. From there, the descent is down the south ridge – but this is complex terrain where scree and boulders require very careful route finding. The final pap – Beinn a’ Chaolais – looks particularly intimidating, and is best ascended (and descended) by heading around to the foot of its east ridge, before more bog trotting leads down to Loch an t-Siob. Be sure to leave enough time for a well-deserved dram at the hotel.

Experience the Jura Fell Race

If walking the Paps is too much, spare a thought for the fell runners who come to challenge themselves on the island’s fearsome fell race. Held annually in late May, the race – a mad twenty-eight-kilometre tumble up and down the scree and heather clad slopes of not just the three main Paps, but four further summits – attracts entries from all over the globe. The winner arrives back at the hotel in Craighouse usually just over three hours after setting out – a quite incredible feat. Respect and bragging rights as well as an obligatory Isle of Jura whisky dram to all finishers, many of whom camp outside the hotel and make a long weekend out of the trip. If you want to compete you need to get in early; the race gains popularity every year with a ballot for successful entries taking place in January. Many fell runners come to Jura to test themselves against the Paps at other times of year.

www.jurafellrace.org.uk

Ride the Corryvreckan whirlpool

Off the remote north coast of Jura, in the Gulf of Corryvreckan, is the third largest whirlpool in the world. There are a number of boat operators who will take you on a thrilling ride to experience it up close. The best times are during high spring tides when the underwater pinnacles cause maximum obstruction to the rushing tidal water between Jura and Scarba, which once led the Royal Navy to declare the strait ‘unnavigable’. The author George Orwell himself had a near miss in these waters and had to be rescued, along with his son, after their boat capsized and they were left clinging to a rock. The whirlpool can also look dramatic from the land at the right state of tide; it’s a long day’s walk along the rough track (no cars) from Ardlussa as far as Kinuachdrachd (look out for otters!) and then follow a final boggy moorland path above the coast to reach a viewpoint overlooking the narrows.

Face Room 101 at Barnhill

George Orwell came to Jura in 1946 seeking isolation and fresh air following the death of his wife and a bout of pneumonia. He stayed with his son Richard and housekeeper at remote Barnhill in the north-east of the island on and off until 1949 and wrote his dystopian classic Nineteen Eighty-Four there. Barnhill is now available to stay in as an off-grid self-catering holiday let. Walkers can peer down at it from the track from Ardlussa on their way to the Corryvreckan whirlpool.

Sample a dram

If it honestly takes longer to get here than to Peru, then you really ought to sample a dram. The Jura distillery runs friendly tours and produces a special bottling for its Tastival whisky festival held here in June to coincide with Fèis Ìle on Islay.

www.jurawhisky.com

Whisky purists may want to visit the source of the water. The walk to Market Loch is a moderate uphill hike alongside a tumbling burn, ending at the tranquil waters of the small loch which is also a popular fishing spot.

Laze on the sands at Corran

The beautiful strand of white sand and sheltered waters at Corran Sands makes this an ideal spot for a paddle on a warm day. Although it’s by far the finest beach on Jura, the huge expanse of shell sand means it never feels busy. It was here that the islanders traditionally loaded their cattle on to boats to send them to market on the mainland. Many Diurachs left their island from this beach, bound for the New World during the years of famine and Clearances.

Investigate the story of Maclean’s Skull with a bothy trip

Jura’s west coast is extremely wild and rugged, but has two open bothies where you can stay and which make a number of mini-adventures possible. The red tin roof of Glengarrisdale is a welcome sight after the arduous boggy walk across the north-west of the island, with only the faintest of paths. A night here could also involve an exploration of Maclean’s Skull Cave, followed by a spot of spooky storytelling in front of the bothy fire. The bothy itself sits just below a rocky crag said to be the site of a castle of Clan Maclean. A clan chief was slain here in a battle against the rival Campbells of Craignish, and his skull sat under an overhang just beyond the bothy for several centuries until the 1970s when it vanished. You may feel the hairs on the back of your neck rise up after a few drams by the fireside. There is also another bothy at Cruib on Loch Tarbert.

Jura Music Festival

Now well into its twenties, Jura’s annual traditional music festival is held every September and has a laid-back vibe. It usually features an energetic ceilidh where you can dance the night away with local Diurachs, a concert in the distillery cooperage and further marquee-based events; festival camping is on the grass in front of the island’s hotel.

www.juramusicfestival.com

Jura, Craighouse harbour

Jura, Barnhill

Jura, distillery

Jura, Evans’ Walk

Jura, Glengarrisdale bothy

Cross the island on foot

Jura is almost cut in half at its middle and here it is possible to walk from one coast to the other in a short, leisurely stroll. From the east coast at Tarbert Bay you can walk west along a track to a picturesque boathouse and a sea inlet on the island’s east coast. Those looking to make a full day out of walking across the island can do so further south; Evans’ Walk crosses the moors using a boggy and wild route, passing just north of Corra Bheinn to reach lonely Glenbatrick – a beautiful spot. Watch out for golden eagles on this route.

Colonsay

Colonsay is small enough to be explored by bike and on foot, yet large enough to keep you busy for at least a week – with spectacular beaches, rugged miniature hills and a vibrant community, it’s a perfect microcosm of the best of the Hebrides.

The island is served by a CalMac vehicle ferry from Oban five times a week in the summer and four times in the winter; there’s also a weekly ferry link to Port Askaig on Islay (enabling a day visit from its larger neighbour). The boats land at the tiny settlement of Scalasaig where there is a general store, cafe/bakery, bookshop, craft shop, village hall and bed and breakfast accommodation. The island’s only hotel is just up the road. A few kilometres over hilly ground (bringing a bike or hiring one is a good option for getting around) brings you to Colonsay House, which has a cafe and gardens open to the public – there is also a nearby bunkhouse. There are self-catering accommodation options scattered across the tiny island.

Kiloran Bay and Traigh Ban

Kiloran Bay is a fabulous beach with custard-yellow sand and a reputation for waves, earning it the wild swimming title of the ‘Colonsay washing machine’. Strong swimmers can test themselves in the bracing waters here. Others can walk along the track for five kilometres past Balnahard to reach the perfect white sands of Traigh Ban – this is usually more sheltered and provides secluded swimming and beachcombing.

Complete the whale sculpture …

Just west of Kiloran Bay lies a 160-metre-long whale – not a beached carcass, but a massive art installation constructed as an outline in local stones by Julian Meredith in 2002. Since then, locals and visitors have been invited to add a stone, and the giant creature’s outline is gradually being filled in. It has recently been recognised as an official landscape feature by the Ordnance Survey.

… and see it at its best

The whale sculpture is hard to appreciate from ground level – the best way to see it is to climb to the top of nearby crag Carnan Eoin. Topped by an impressive cairn overlooking Kiloran Bay, this is the highest summit on the island and Colonsay’s finest viewpoint.

Bag the MacPhies

If just one hill isn’t enough, Colonsay has its own ‘mini Munros’. The MacPhies are twenty-two hills above 300 feet (ninety-one metres) that are dotted across the island. With much tough terrain, the challenge to complete them all in a day involves a gruelling thirty-two-kilometre hike. The record time to beat currently stands at just under four hours.

Drink in Colonsay’s finest

Colonsay claims to be the smallest island in the world with its own brewery, which opened well before the recent boom in craft ales. It produces three very quaffable brews as well as special occasion bottlings. The brewery has recently been joined by a small distillery, as Wild Thyme Spirits are now producing Colonsay gin, allegedly with the help of spirit helpers or ‘brownies’ who traditionally crop up in Celtic mythology, residing in people’s houses and helping with the household chores.

Bee happy

Colonsay is one of the last places in the country where the Scottish native black honey bee is thriving under the custodianship of legendary beekeeper and oyster farmer Andrew Abrahams. Colonsay’s black bees are the only ones thought to be isolated enough to prevent interbreeding with imported bees. They are now specially protected in law – it is an offence to bring other honey bees to Colonsay and Oronsay. Their very special honey can be sampled at the shop and cafe.

Ceòl Cholasa

Every September the village hall is buzzing with creative talent, both island-bred and from far afield, as Colonsay celebrates its music festival. Many people come year after year to enjoy and take part in the super-friendly folk-based concerts and ceilidhs, with further sessions in the hotel bar till the wee hours.

www.ceolcholasa.co.uk

Book festival

Taking place in April, this low-key literary event attracts top-name authors despite the remote location. Previous guests have included Alexander McCall Smith, A.L. Kennedy and Val McDermid.

www.colonsaybookfestival.org.uk

Colonsay, Beinn nan Gudairean – a MacPhie

Colonsay, whale

Colonsay, Scalasaig

Oronsay, beach

Oronsay, post office van crossing the strand

Oronsay, Priory cross

Oronsay

This small but fascinating island lies just off the southern shore of Colonsay. Crossing the tidal strip of exposed sand known as The Strand at low tide to visit Oronsay is a must. Check the tide times very carefully with locals as the crossing can be dangerous, and be sure to make the outward journey as early as possible during the falling tide. A bit of paddling will usually be required – and you may see the post office van splashing through the shallows to deliver to the island. Oronsay is home to eight people but there are no facilities for visitors.

Oronsay Priory

Be sure to visit the fourteenth-century ruined priory, complete with an ossuary where you’ll see human skulls and bones. Outside stands a very fine carved Celtic cross. As long as you cross The Strand on a receding tide you should have time to walk to the priory, explore a little and visit one of the fine beaches and return to Colonsay before the tide cuts you off.

Hear the rasp of the corncrake

A relative of the moorhen, the corncrake was once widespread across Britain, but changes in farming practices saw its range shrink catastrophically until it remained on only a few Scottish islands – including here. Oronsay is farmed by the RSPB in a corncrake-friendly manner and you may well hear their unique rasping call on a visit in summer – they are notoriously difficult to see as they hide in the uncut grasses.

Gigha

This uncharacteristically fertile island lies four kilometres off the coast of the Kintyre peninsula, its green and verdant character lending it the nickname ‘God’s island’. Gigha had a succession of private owners before a buyout by the local community in 2002. The population has expanded since and although it hasn’t all been plain sailing, new businesses have been developed and the future looks positive.

A regular CalMac vehicle ferry links Gigha to Tayinloan on the Kintyre peninsula, operating seven days a week. The jetty is at Ardminish, the main cluster of houses on the east coast of the island; the island’s hotel is here, together with the shop, post office and an art gallery. There is around eight kilometres of quiet road from one end of the island to the other, making cycling or walking the ideal means of transport for visitors.

Climb Creag Bhan

Though only 101 metres high, this is the island’s highest hill, its name translating as the White Rock. It’s easily climbed by turning off the road on to a signed track at Druimyeon More. Keep right at a fork in the track and then look for a signpost indicating the start of the path to the top. From here the whole of Gigha can be seen, as well as Kintyre, the islands of Jura, Islay, Mull on a clear day and even Northern Ireland if you are blessed with perfect conditions.

See the gardens at Achamore House

These twenty-hectare gardens just a kilometre from the ferry jetty are run by the community. They contain a vast array of rhododendrons and azaleas collected by the former owner of the island – and inventor of the malted milk bedtime drink – James Horlick.

The Twin Beaches

It’s well worth walking or cycling to the less-populated northern end of the island, passing a fine standing stone along the way. Climb up to the North Cairn for stunning views towards the Paps of Jura, and then head for the narrow isthmus that links Eilean Garbh to the rest of the island, with beaches on either side. The southern beach of Bagh Rubha Ruaidh is pleasant enough, but the real gem is north-facing Bagh na Doirlinne across the narrow dune-like spit; the fine sand here makes for a truly stunning spot.

Gigha music festival

This tiny, friendly traditional music festival attracts some fantastic bands and many of the best of Scotland’s young musicians to Gigha towards the end of June. The 150-capacity village hall is usually crammed to bursting. Other events include a Piper’s Picnic, a big ceilidh (the festival claims the record for the longest continuous Strip the Willow – sixty-five minutes), late-night sessions in the island’s hotel, a barbecue and a last night survivors’ concert. www.gighamf.org.uk

Raft race

Usually held towards the end of July, this fun event is organised by the island’s restaurant and sees teams racing an array of home-made rafts across the bay.

Cara

This small, uninhabited island is a kilometre south of Gigha, which would be the best place to try to find a boatman if you want to make a visit. It is said to be the only Scottish island still owned by a descendant of the Lords of the Isles (originally based on Islay), but the only inhabitants today are a herd of feral goats.

Gigha, view to Paps of Jura

Gigha, Twin Beaches