Berneray, West beach

Overview map part 1

Lewis

The most intriguing thing about the Isle of Lewis (Eilean Leodhais) is that it isn’t an individual island at all. Its conjoined twin, the Isle of Harris, comprises the southernmost third of the land mass, divided by rocky mountains from Lewis in the north. Lewis has the largest population in the Hebrides and contains the administrative capital of the Western Isles (or Outer Hebrides), Stornoway.

The main ferry route to Lewis plies between Ullapool and Stornoway. Taking just under three hours, the service runs twice a day, with extra sailings during peak summer times and reducing to one sailing on winter Sundays. There is also the option of taking the ferry from Uig on Skye to Tarbet in Harris and continuing by car, bus or bicycle on to Lewis. Ferry operator CalMac also sells a Hopscotch ticket which allows numerous combined journeys within the Outer Hebrides on one ticket. All of these ferries take vehicles. Air travel has increased in recent years with regular direct flights to Stornoway from Glasgow, Inverness, Edinburgh and Manchester. Loganair is the main operator.

Lewis has all major services and a good mix of accommodation options. However, as most of the settlements are on the coast with major services centred in and around Stornoway, do bear in mind that in remote places the nearest shop or petrol station can be a long way away. Note that most services are closed on Sundays, including the big supermarket in Stornoway, so you may need to plan ahead. However things are changing fast and it’s no longer the case that tourists go hungry on the sabbath as many more cafes, hotels and restaurants open their doors.

See the Butt

Keep heading north and you will eventually reach the most northerly point on the island, the Butt of Lewis. Topped by an unusual brick-built lighthouse, this spot gained a place in the Guinness Book of Records for being the windiest place in the UK. It’s certainly always pretty breezy, but on stormy days the waves crashing against the high cliffs and sea stacks become truly spectacular. If the elements allow, a dramatic circular walk leads along the coast to the stunning sands of nearby Eoropie beach, passing a natural arch on the way. Behind the dunes lies one of the largest and best equipped play parks in Scotland – be warned it can be hard to prise children of all ages away.

Take the peat road

The Pentland road (Rathad a’ Phentland) stretches across the wild open moors between Stornoway and Carloway in the west. Originally planned as a railway which it was hoped would hasten the transport of fish from the fishing station at Carloway on towards markets on the mainland, the road was completed in 1921. Driving, cycling or running across this seemingly desolate landscape reveals a land carved by local hands for generations. The deep peat cuttings on both sides of the road, many of which are still worked today, are the scars where peat has been hefted from the sodden ground. This was traditionally a communal effort, with peats being cut in late spring and left to dry on the ground for a month or so before being piled on to carefully constructed stacks usually adjacent to the house and in past times often rivalling the size of the house itself. Peat burns fairly cool so a household could easily get through 1,500 peats in a winter. Nowadays, less backbreaking forms of heating are available, but many locals still have the rights to cut peats from a personally allocated peat bank, and sales of the tairsgear, a traditional peat cutting tool, have risen recently as more people use this free, if labour-intensive, form of fuel. While the peat road is used as a shortcut by some locals, it can feel utterly deserted and desolate – especially with a storm brewing. A good place to recall stories of ancient bog burials, or as the setting for the latest of Peter May’s Lewis-based tartannoir novels, but not a place to break down. The views are best when heading west, but if cycling the headwinds can be cruel and facing east is the better option.

Stand amidst the stones at Callanish

Visit the windswept site at Callanish at sunset or early morning and watch the light change on these enormous prehistoric standing stones. Five rows of stones form a large cross shape, and near the centre of the arrangement stands a massive monolith almost five metres high. The stones are thought to date from between 2900 and 2600 BC, with a later chambered cairn lying in their midst. While some stones line up with various phases of the moon, the true purpose of the site remains unknown, although local folklore explains the stones are the petrified remains of giants who refused to convert to Christianity. There’s a visitor centre and several smaller stone circles nearby.

Cross the Bridge to Nowhere

This curious, well-constructed bridge was once part of an ambitious plan by the island’s one-time owner, Lord Leverhulme, to build a road up the east coast of Lewis. The bridge lies just north of Tolsta near a spectacular beach, and is all that remains of the grand plans for a road all the way to Ness. The road, now just a rough track, peters out about a mile further on with the rest of the route a tough walk over relentless bog and dramatic coastal ravines and clifftops. The bridge features in Peter May’s thriller The Chessmen as the scene of a teenage scooter race.

Leverhulme owned Lewis and Harris between 1918 and 1923. Having made his fortune in soap (the company eventually became the global giant Unilever), the English businessman turned his attention to projects aimed at modernising and industrialising this outpost of the British Isles. Many of his projects proved overly ambitious or lacked much local support; the Bridge to Nowhere provides a metaphor to folly.

Retreat to Dun Carloway broch

Explore the double-walled tower that would once have provided a defensive refuge for locals during Norse raids. Built in the first century, Dun Carloway is a fine example of a broch, a round and heavily fortified structure unique to Scotland. This impressive ruin sits alongside an underground visitor centre which can be used as the starting point for a rugged moorland and lochans circular walk.

Na Gearrannan blackhouse village and the west side

The best of the west coast scenery is revealed to those who venture on foot. A challenging nineteen-kilometre linear hike from Bragar takes in natural arches, sea stacks and sandy coves and as it mirrors a bus route it’s possible to cut this linear walk short at a number of places. The cliffs are perfect for watching seabirds as well as keeping an eye out for passing sea creatures, including dolphins, porpoises, whales and – of course – curious seals. The added bonus is that the hike ends at the atmospheric Na Gearrannan blackhouse village, a restored thatched settlement where, in addition to visiting a museum, you can stay overnight as some of the cottages provide self-catering and hostel accommodation.

Lewis, lighthouse at the Butt

Lewis, peat stacks

Lewis, Callanish stone circle

Lewis, Dun Carloway broch

Lewis, Bridge to Nowhere

Lewis, cleared village of Stiomrabhaigh

Lewis, west side coast walk

Lewis, Uig Sands

Lewis, heading towards Mealaisbhal

Enjoy a well-earned strupag

Around half the 27,000 people living in the Outer Hebrides can speak Gaelic and you will encounter the Celtic language everywhere – road signs, menus, place names, songs and in overheard conversations on the bus or in the cafe. While there’s no necessity to learn any Gaelic to visit this bilingual outpost, it’s fun to pick up a few words to help understand the names on the map and local names for the wildlife. Local ceilidhs will often include Gaelic singing – keep an eye out for Feis events or the annual HebCelt Festival. There are a number of leaflets and websites that can help, but chance encounters with native speakers, maybe over a strupag – or cuppa – in your B&B, can be more illuminating. Slàinte!

Dig in at Uig sands

These fabulous sands are where the Lewis chessmen were unearthed in 1831 by a local crofter. Carved from walrus ivory in the twelfth century, they are likely to be Norse, this part of Scotland being under Norwegian rule at that time. The pieces are incredibly lifelike, many with expressions we now associate with boredom, madness and grumpiness. Experts believe the ninety-three-piece hoard may actually be made up from five different chess sets, but this is a place to abandon all thought of treasure hunting to instead relax on Lewis’s most spectacular beach.

Explore a cleared village

The walk over rough moorland to Stiomrabhaigh from the remote settlement of Orasaigh may convince you that no one could ever have lived in this forbidding environment. However a quick look around the location high above the lochside reveals the remains of sturdy stone-built dwellings, the telltale ridges of lazy beds, where potatoes and barley would have been grown, the near landscape green against the brown, heather-clad hillside hinting at the cultivation and animal husbandry of the past. In fact, eighty-one people lived in Stiomrabhaigh in sixteen houses in 1851. Eight years later the whole village had been cleared by the landowner to make way for deer. Later the settlement was inhabited again before finally being abandoned in the 1940s. More recently, much of this area, Pairc, has been purchased by the local community who are now in charge of their own land.

Climb Mealaisbhal

Hiking to the highest point on Lewis is worth it for the journey to the start alone. Sitting proud of the other Uig hills on the far west of the island, Mealaisbhal has to be sought out. The journey passes the sandy beaches of Uig and Mangersta, continuing through scattered crofting townships well beyond the tourist trail. The start from Breanais is unprepossessing – heading directly towards the looming hill on an old peat-cutting track which soon deteriorates into a bog. Reaching the rock-strewn slopes of the hill is a relief and the climb gradually rewards with ever-expanding views. From the 574-metre summit the Uig sands, surrounding mountains and watery landscape lie beneath. Expect to be up and down in around four hours. Hardened hillwalkers keen on rocky, pathless scrambling can climb Mealaisbhal as part of a very tough circuit of the Uig hills.

Attend a Gaelic psalm service

Lewis and Harris have a very high level of church attendance – and sabbath observance – compared to the Scottish mainland, and while these traditions are changing fast, Sunday is still a quiet day with very few shops open. The Free Church of Scotland is the main church here, followed by the Church of Scotland and the Free Presbyterian Church of Scotland. Many will hold a Gaelic service in the morning and an English service in the evening, and unaccompanied Gaelic psalm singing is a unique and remarkable experience. Visitors are welcome to attend services – community noticeboards will often give the times – although you should ask locally what is required in the way of dress code as smart clothes and hats are still expected at many churches.

Shuck a scallop

Sampling local, fresh seafood is a must during any visit to the Outer Hebrides. Much of the catch makes its way to mainland Europe and with restaurants far flung in this remote community it’s not always easy to source despite the number of creel pots and tiny fishing boats seen around the coast. Luckily the Scallop Shack on Uig pier provides a steady stream of ultra-fresh scallops, mussels and oysters prepared for you to take away and cook. Open all year, the shack also has a cafe serving lunches and takeaways in the summer months – dig in!

Eilean Chaluim Cille

One of at least three Scottish islands bearing this name – which means ‘the isle of St Columba’ – this one is a tidal isle at the entrance to Loch Erisort on Lewis and is best reached from Cromor in South Lochs.

Discover the ruins of St Columba’s Church

Check the tide times as the causeway to Eilean Chaluim Cille is only crossable for a couple of hours either side of low tide and make sure you leave plenty of time to complete the two-kilometre each way walk from Cromor. Start by taking the track towards the island, passing a number of houses before crossing the causeway, often slippery with seaweed. Once on the green and fertile island bear left to visit the remains of the ancient monastery and church. It is thought that St Columba’s followers first built a church on this site around AD 800. The site certainly retains a tranquil and spiritual atmosphere to this day, even though your only companions on this now uninhabited island are likely to be sheep.

Great Bernera

Four thousand people turned up to walk across to Great Bernera when the bridge was opened in 1953. Known as Beàrnaraigh Mòr in Gaelic, the island is often referred to simply Bernera or Beàrnaraigh, and the fact that a bridge was built at all was testament to the spirit of the inhabitants who had threatened to take matters into their own hands with a plan to blow up the cliffs to form a causeway. Today’s easy access means the island has a sustainable population and a future to match its long history of habitation dating back to Viking times.

Visit the Bostadh roundhouse

In addition to the large standing stone and ancient broch that greet you as you come over the bridge, a large Iron Age settlement lies preserved at the spectacular beach at Bostadh. Uncovered by a storm and since reburied, a replica roundhouse has been built nearby. It can be visited from a nearby parking spot or as part of a half-day (eleven-kilometre) circular walk from Breacleit. It’s easy to imagine yourself back in Pictish times as you descend towards the sea and eventually open the door of the thatched building to explore inside.

Pabbay (Loch Roag)

Actually a linked pair of small islands (Pabaigh Mor and Pabaigh Beag) in Loch Roag, Pabbay has a starring role in The Chessmen, one of the books in the Peter May’s Lewis trilogy, when a boat chase ends in tragedy in one of the island’s caves on the day of the Uig Gala. The gala is a real event taking place each July on Reef beach (Traigh na Beirghe) on Lewis and boat trips often run out to Pabbay during the day – otherwise Seatrek can organise a trip.

Harris, approaching An Cliseam on the horseshoe

Harris, tweed

Harris, An Cliseam summit

Harris, Huisinis beach

Harris, Rodel church

Harris

Harris is Lewis’s rough and ready southern sibling – all mountains, wild bog and vast sandy beaches. While technically not an island in its own right as it’s part of the same landmass as Lewis, it is always referred to as the Isle of Harris and has its own distinct geography and culture – and deserves bagging rights of its own. Tarbert, situated at the narrow waist which almost divides Harris in two, is the main centre and this is where the CalMac ferry from Skye docks. There is a hotel, shops and a school here. A recent tourist boom across the Outer Hebrides has increased the accommodation options across the island, but it’s always advisable to book in advance in the summer months. A fairly fast road links Tarbert with Lewis to the north, while the ferry on to Berneray leaves from Leverburgh in the south.

Climb An Cliseam

The Harris hills are rough and unforgiving but the ascent of An Cliseam (Clisham) – the highest in the Outer Hebrides – is rewarded with stunning views over mountains and endless seas. The 799-metre-high summit is not so far from the road, yet it isn’t obtained easily – the most direct route climbs relentlessly across boggy then rocky ground from the A859 and for a fit walker it’s possible to get up and down in under four hours. A much more satisfying route, known as the Clisham horseshoe, makes a day-long circuit by approaching via the ridges of Mulla-Fo-Thuath and Mulla-Fo-Dheas. With some scrambling in places, it’s regarded as a Hebridean hillwalking classic and definitely not one to miss if you have the necessary skills and experience.

Look out for the Orb

Self-sufficient Harris folk have traditionally spun wool from their sheep and woven it into cloth, using dyes from local plants and lichens and urine to ‘fix’ the colour (many croft houses would have had a large pisspot outside to collect this valuable asset). After spinning, the cloth would be created on a loom and then the fabric ‘waulked’ – or finished – by repeatedly soaking and thumping it rhythmically, often by a group of women singing traditional Gaelic ‘waulking’ songs to keep time. Today, Harris Tweed is still produced by hand and it is world-famous – and protected by the Orb trademark. Look out for signs to modern-day weaving sheds where the production techniques have changed little over the years; many will have lengths of cloth for sale and often finished products in this iconic fabric.

Huisinis beach hunt

Quite possibly the most scenic drive in the Outer Hebrides, the last few miles of single-track B887 from near Tarbert provide stunning views across Loch a Siar to the island of Taransay. The sands at Huisinis (Hushinish) are the main draw, and while this pristine white strand is often completely deserted, there are even more isolated and pristine beaches just waiting to be discovered just out of view. Follow a rough path north from the parking area eventually walking under the imposing flank of Sròn nam Fiadh and alongside Loch na Cleabhaig, passing a lonely cottage before reaching the sandy beach at Crabhadail.

Gawp at the Sheela-na-gig at Rodel church

Found on religious buildings throughout Europe, Sheela-na-gigs are stone-carved female figures pointing to or pulling open their vulvas. It is thought they served the same purpose as grotesques or gargoyles to ward off evil spirits, but the immodesty of the Sheela-na-gig suggests the possible survival of a pagan goddess into Christian times, a fertility symbol or even a warning against the dangers of lust. Make your own mind up as you search out the walls of beautiful and ancient St Clement’s church in Rodel for this fine example.

Cycle the golden road

So called because of the extremely high cost of construction, the ‘golden road’ runs down the rocky lunar landscape of the east side of Harris from Tarbet to Leverburgh. The project was government funded, partly to provide children with access to schools. The route links a number of tiny coastal settlements on the rough heather and rock moonscape that contrasts so vividly with the sandy coastal strip on the west. Today this quiet switchback road is a cyclist’s dream, passing numerous tidal inlets with the chance to get close to otters and eagles. As always in the Outer Hebrides, the weather will decide how arduous the twisty-turny, uppy-downy road will feel from the saddle.

Claim your own stretch of perfection

The west coast of Harris is brimming with spectacular golden sandy beaches. The huge expanse of Luskentyre is many people’s pick as the finest in all the Hebrides, and with its backdrop of Harris mountains it is spectacular. If you have the time, however, why not seek out your own strand and make your claim? The A859 snakes down the island’s west side and is dotted with magnificent beaches, often backed by colourful machair or dunes. Leave no trace and these often deserted sands can be yours for the day – check out the shoreline for otter prints and scan the waves for birds or dolphins.

Harris, Traigh Iar

Harris, the Golden Road

Scalpay

Joined to Harris by an elegant bridge which opened in 1997, Scalpay is one of a growing number of Scottish islands owned by its residents, in this case thanks to the previous owner who gifted the island to the community. Blessed by two great natural harbours, Scalpay has traditionally been an island of fishermen, with an equally thriving female-driven knitting industry. In recent decades fishing has declined in importance and the replacement of the ferry by the bridge has seen more people move to the island, making it easier to commute to Tarbert or elsewhere. Approximately 300 people currently live on the island, many of them in or around North Harbour (An Acairsaid a Tuath). The interior is rugged and dotted with lochans. Scalpay has a bed and breakfast, a number of self-catering options and two cafes.

Visit the first lighthouse in these isles

The first lighthouse to be built on the Outer Hebrides, Eilean Glas stands at the far south-east corner of Scalpay. You can still see the stump of the original lighthouse, built in 1789 but replaced less than forty years later by the red-and-white-striped Stevenson tower that stands today. You can visit it as part of a circular ten-kilometre hike around Scalpay, following rough waymarkers and exploring moorland lochans as well the island’s highest point with views to Skye on a clear day.

Tickle your taste buds at the North Harbour Bistro and Tearoom

With so much fine seafood being caught by fishermen from this island it would be shame to leave without sampling some of it. This friendly bistro and tearoom is the place to do it. In addition to seafood, the imaginative cooking – think Masterchef final without the presenters’ gurning – really showcases the local produce. Booking is essential for evenings, but they also rustle up a mean soup and scone at lunchtime.

Taransay

Taransay is best known for its starring role in the early reality TV show Castaway 2000 when thirty-six people were tasked with building a community on this small island just three kilometres off the Harris coast. Owned by the Borve Lodge Estate, it is possible to visit by kayak or private charter; Seatrek, based on Lewis, occasionally runs trips here.

Harris, Luskentyre and Taransay

The island once supported a number of crofters in three settlements but the last family left in 1974. Since then there have been no permanent residents except a herd of red deer, large bird populations and sheep grazed here. In addition to the more modern properties you can still see the remains of two ancient burial chapels at Paible. The island is almost split in two, a narrow strip of land joining the two sections both of which have a notable small hill and a number of sandy bays backed by machair awash with flowers in early summer.

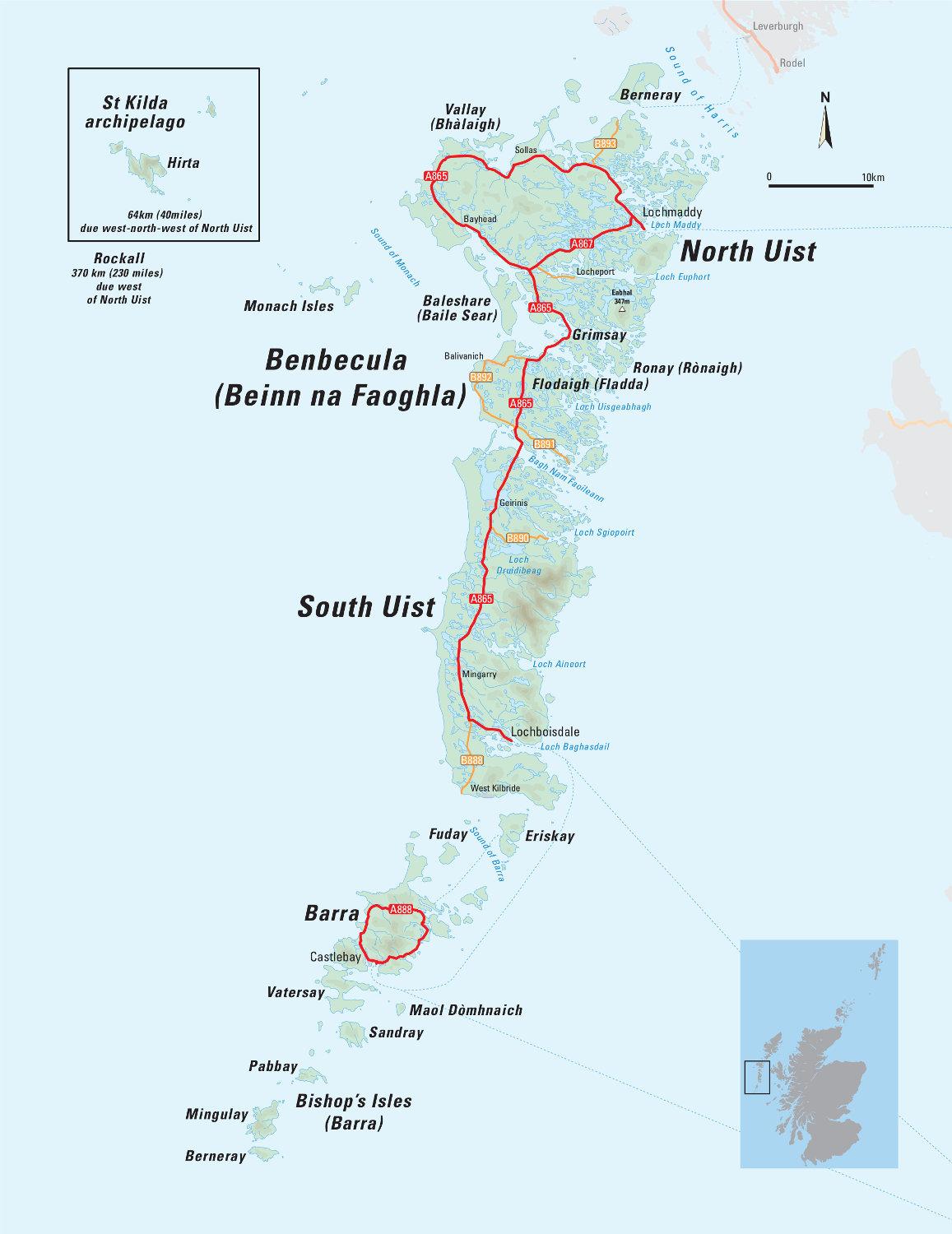

Overview map part 2

Scarp

The number of buildings still standing on Scarp is testament to the thriving community that once lived here. Lying just off the west coast of Harris and only a short distance from Huisinis, Scarp has been uninhabited since 1971; the maintained houses are now used as summer holiday homes. The narrow strait was the site of a postal experiment in 1943 when German inventor Gerhard Zucker used rockets to deliver mail over the sea to the island. As the singed remains of letters rained down, it became apparent this was not a permanent replacement for the local waterborne postie. Lacking a rocket launcher, the only way to reach Scarp today is by boat or kayak.

Pabbay

A few kilometres west of Leverburgh on Harris, Pabbay is a low-lying green island with some amazing sandy beaches. So fertile it became known as the ‘granary of Harris’, it was once home to over 300 people before being cleared to make way for sheep by 1846. It is now uninhabited. Pabbay residents were renowned as skilled illicit distillers, putting their ample barley crops to good use and working alongside the ferrymen on Bernera who would hoist a warning flag if they had excisemen on board so as to give time for evidence to be hidden. However, a successful raid provided evidence then used by the landlord’s factor as the basis for the later evictions, eventually leaving only one shepherd and family on the island. The ruins of houses can still be seen amidst the grazing sheep and deer. It is possible to charter a boat from Seatrek on Lewis.

Flannan Isles

This small group of islands – also known as the Seven Hunters – lies thirty-four kilometres north-west of Gallan Head on the Lewis coast. Visits are only possible through private charters, but there is no sheltered anchorage for yachts.

The largest island, Eilean Mòr, is home to the Flannan Isles lighthouse, itself the setting for an enduring mystery. Just before Christmas 1900 the three lighthouse keepers seemingly vanished off the face of the earth with no obvious explanation. The disappearance spawned a cottage industry in theories including abduction by pirates, being eaten by seabirds or a cabin-fever quarrel that got out of hand. More recent historians suggest that stormy seas and an accident were most likely to blame, but no remains have ever been recovered. The lighthouse was automated in 1971 which is when the last residents left.

St Kilda Archipelago

Scotland’s Ultima Thule, St Kilda is at the top of many island baggers’ wish lists, with the long, long journey west to the isolated island group over eighty kilometres west of Harris becoming something of a pilgrimage.

St Kilda (Hirta), Boreray, from Conachair

St Kilda (Hirta), looking over Village Bay from Conachair

St Kilda, Stac Lee, Boreray

Left and Right: St Kilda (Hirta), the houses of Village Bay

There are now many day trips to the islands, most of which allow between four and five hours ashore on the largest island, Hirta, together with a cruise around Boreray and its great stacks. The fastest crossing from Leverburgh on Harris takes around two hours each way, but many of the boats are slower and actual journey times depend on the weather and any stops for wildlife viewing. Go to St Kilda operates trips from Stein on Skye.

All trips to St Kilda are prone to cancellation due to poor weather so it is best to be flexible with your plans. Some operators will arrange longer trips allowing stays at the basic campsite at Village Bay which is run by the custodians of St Kilda, the National Trust for Scotland. It is also possible to spend a week or longer as a volunteer with the Trust undertaking conservation work.

Top out on Hirta

On a clear day, climbing to the highest point of the archipelago is a fantastic way to appreciate the isolation of St Kilda, experiencing the immensity of its cliffs and imagining the hardships of scratching a living from them.

Once ashore, head right from the pier, skirting round the army base buildings and aiming uphill, passing a number of stone-built cleits or shelters used by the St Kildans to store peats, eggs and other foodstuffs. Aim for The Gap where suddenly the climb gives way to a cliff plunging 150 metres vertically to the sea. The residents of St Kilda were skilled climbers who used these cliffs to catch seabirds for food and oil and also to collect eggs. From The Gap continue to the left, heading up steep ground populated with often angry nesting bonxies (great skuas) in the summer months, to eventually reach the summit of Conachair (430 metres). The stone trig point teeters frighteningly close to the sheer cliff edge – Conachair has the highest sea cliff in all Britain – and the view out to Boreray and its stacks is unique.

A 200-metre detour leads to a second trig point which gives an aerial view of Village Bay and the neat row of houses occupied until the island was evacuated in 1930. The quickest descent is to take the track down from the Ministry of Defence station to leave enough time to explore the poignant remains of the village, museum, church and schoolroom.

Join the St Kilda parliament

Every day the men of St Kilda would line the main street for their parliament meeting where the day’s activities would be decided on and any matters of discord in the community resolved – presumably while the women got on with work. Everyone was free to speak and there was no one in charge – decisions had to be agreed upon. Various visitors from Martin Martin in 1697 onwards, including a steady stream of intrepid ‘tourists’ in Victorian times, recorded that there were few long-term divisions in the St Kildan society and that no serious crimes had been committed.

The last residents were evacuated from St Kilda in 1930 at their own request, the population having been ravaged by a combination of disease and emigration. The last person to be born on St Kilda died in 2016 although descendants still visit. Today you can wander into many of the ruined houses – look out for the pebbles placed near the fireplaces that record the names of the last inhabitants.

Spot the St Kilda wren

The island group’s isolation from the rest of Scotland means it has become something of an evolutionary test case, a more northerly and considerably more bracing Galápagos. Keen-eyed island baggers may be lucky enough to spot the St Kilda wren, which has adapted to life on the island and is different enough from its mainland cousins to qualify as its own sub-species (Troglodytes troglodytes hirtensis to give it its Sunday name). While slightly larger than a normal wren, it is also greyer with more obvious stripy markings but is still hard to spot as it flits amongst the stones and cleits on the island. There’s also a St Kilda mouse.

See the great stacks of Boreray

Stac an Armin and Stac Lee project from the sea near the tiny island of Boreray like sharks’ fins. Housing an unfathomable number of seabirds, the stacs present a whirling mass of feathers when viewed from the sea during the nesting season. The stacks are the highest in Britain, and both are Marilyns (hills with a relative drop of 150 metres all the way round), presenting perhaps the ultimate challenge to hill baggers. Getting ashore, let alone climbing up the guano-covered rock, is a very serious undertaking, and given the protected status of this National Nature Reserve is only permitted outside the bird nesting season.

Boreray is the smallest Scottish island to have a summit over a thousand feet high – Mullach an Eilein, at 384 metres – and it appears as a great mountain rising sheer from the sea. Landing is difficult, yet incredibly there are prehistoric remains that suggest an early farming community survived here. In more modern times, eleven St Kildans were marooned on the island over winter in 1727 when a smallpox epidemic meant there was no one able to row over to rescue the group which had been left on Boreray to undertake a fowling trip.

St Kilda, Boreray

Cruising round the stacks and Boreray is an incredible experience, visiting these fearsome cliffs up close and marvelling at the St Kildans who regularly climbed the stacks hunting fulmar, gannets and other seabirds, and collecting eggs.

Rockall

This tiny block of granite projecting from the open Atlantic lies over 300 kilometres further west even than St Kilda. It was first claimed by the UK in 1955 when two marines and a naturalist raised a flag on the rock and affixed a plaque – though this has long gone. It became part of Scotland in 1972, although Ireland has never recognised the UK’s claim.

Fewer than twenty people have ever set foot on Rockall, and it remains a magnet for eccentric adventurers and the most extreme of island baggers. Explorer Nick Hancock managed to survive forty-three days on it in 2014, breaking the previous solo record of forty days set by a former member of the SAS in 1985.

It is hard to imagine a more forbidding place than this bare rock out of all sight of any other land. For most island baggers it remains forever just a dream – or perhaps a nightmare.

North Rona

Actually just named Rona, it is often referred to as North Rona to distinguish this isolated island from the Rona off the coast of Skye. Lying seventy-seven kilometres north of the Butt of Lewis it is seriously remote, the perfect spot for the medieval hermits who came to live here, following in the footsteps of St Ronan who is thought to have stayed in the eighth century. Life would certainly have been tough, and there is evidence that at one point in the seventeenth century the population died out from a combination of starvation and the plague.

Shepherds clung on as residents until 1844 when the owner made an offer of the island for use as penal colony. This was declined by the government, and the island has remained uninhabited ever since. It is possible to make the long journey by chartering a boat, and Seatrek will sometimes run trips although landing can never be guaranteed. Exploring the grassy island on foot is relatively easy once ashore and the remains of settlements and the chapel are easy to make out.

Sula Sgeir

Sula is the Norse word for gannet and it is this elegant seabird that dominates and makes its home on the tiny rocky island of Sula Sgeir, sixty-four kilometres north of the Butt of Lewis. For centuries men from Ness have journeyed out to this remote rock to hunt the juvenile gannets, or guga, for their meat and feathers. This controversial tradition carries on today under a special licence issued by the Scottish Government. The resulting guga meat is highly prized by those who have acquired the taste – heavily salted, it is best accompanied by a large glass of milk. As the hunt is limited to 2,000 birds, the guga meat is rationed and sold on the quayside when the annual hunt boat returns. It is possible to visit Sula Sgeir by chartered boat, often in combination with a longer trip to North Rona. If a visit is not possible, watching the fascinating 2011 documentary The Guga Hunters of Ness will give you an insight into the local tradition as well as many views of the forbidding island scenery.

Shiant Islands

The Shiants are a group of small islands renowned for their seabirds, and lie approximately seven kilometres from the Lewis coast in the Minch, the waters between Skye and the Outer Hebrides. Geologically a continuation of the Trotternish Ridge on Skye, the rock is volcanic and forms some impressively high sea cliffs providing a natural haven for seabirds, particularly puffins and razorbills as well as Manx shearwaters and European storm petrels.

Getting to the Shiants usually involves a private charter from either Skye or Lewis unless you have your own boat or kayak. There is a bothy on the island which is available for visitors to stay in with the arrangement of the owner, Tom Nicolson. Tom’s father, Adam, wrote a fine book about the islands called Sea Room, as well as a more recent discussion about the future of our seabirds and oceans, The Seabird’s Cry.

www.shiantisles.net

Berneray

The only inhabited island in the Sound of Harris, Berneray is linked to North Uist via a causeway which was opened in 1999, and to Leverburgh on Harris by a CalMac ferry. Berneray supports a population of around 130, most involved in crofting. There is a shop, cafe and post office, as well as a community centre, two hostels and a number of bed and breakfast and self-catering options. In the summer, the old Nurses Cottage houses displays on history, ancestry, crofting and wildlife, as well as information about facilities on the island – follow the east road to find it.

Berneray, hostel

Stay in a blackhouse

The picturesque hostel on Berneray is run by the Hebrides-based Gatliff Hebridean Hostels Trust. Converted from a traditional blackhouse, it’s actually painted white. Dubh is Gaelic for black and some say the name comes from the dark interior and peat, but it could also be a corruption from tughadh which means ‘thatched’, and used to differentiate from the more modern harled ‘white houses’ that often replaced the blackhouses. These dwellings would have housed the family at one end and their livestock partitioned off at the other, providing a source of warmth in the winter. The hostel sits right on the beach and is a wonderful place to swap island tales with other travellers.

Watch for otters from the causeway

The first thing to notice as you approach the causeway to Berneray is the Caution Otters Crossing road sign. When the causeway was built in the late 1990s several underwater otter runs were incorporated in the structure to allow the otters to pass through – but you still need to watch out for any on the road. Almost anywhere on the coast of Berneray is good for otter spotting, and they are most likely to be seen on a rising tide. Scan the water for the telltale V-shape created as they swim. They often come ashore to eat crab, butterfish or some other tasty prey, but are easy to lose amongst the kelp and rocks. Their footprints in the sand are also a giveaway as otters have five toes in comparison with a dog’s four. Keep binoculars handy, and if you do fail to spot this elusive creature check out the otter sculpture on the roof of the thatched hostel.

Climb Beinn Shleibhe

Much of Berneray is low-lying, fertile machair. For the best view climb to the trig point atop Beinn Shleibhe from where there are panoramic views over the whole island as well as nearby Pabbay and the mountains of Harris. Climbing this ninety-three-metre high point can easily be incorporated into a circular walk around Berneray which can also include the impressive Cladh Maolrithe standing stone.

Visit the great West Beach

No visit to Berneray is complete without a frolic on the stunning sands of the five-kilometre-long West Beach – so good they were once used by the Thai tourist office to promote their own beaches. Start from the community hall and head out, passing some prehistoric remains including an ancient souterrain before crossing the machair and dunes to reach the beach.

Berneray, causeway to North Uist

North Uist, Eaval

North Uist

A remarkable watery landscape of blue, green and purple, North Uist consists of peat moorland dotted with innumerable lochans and bog. In fact, over half the ‘landmass’ is covered with water, and the divide between salt and freshwater is frequently unclear.

The main settlement Lochmaddy is linked by CalMac vehicle ferry to Uig on Skye. North Uist is also linked by causeway to Berneray in the north (from where a ferry runs to Leverburgh on Harris), and to Benbecula via Grimsay in the south. Most of the shops and accommodation, which includes a hotel, is in Lochmaddy, as well as Taigh Chearsabhagh, a fine arts centre and museum. There are self-catering cottages to rent dotted around the island.

See no Eaval

An ascent of Eaval is the perfect introduction to the watery landscape of North Uist. The bird’s-eye view from the summit of this conical hill looks down on a maze of tiny lochans and larger sea lochs. The route starts from the end of the road heading along the south side of Loch Euphort. The often-wet approach soon runs alongside Loch Obasaraigh, crossing an outflow that can be impassable at the highest tides. There are good views to the cone-shaped Eaval and the climb soon begins in earnest, eventually reaching the trig point and shelter cairn marking the 347-metre summit; it boasts a unique view that will never be forgotten.

Try peat-smoked salmon from the Hebridean Smokehouse

The Hebridean Smokehouse has been combining the flavours of salmon and peat smoke for almost thirty years. A truly locally produced food, the fish and shellfish all comes from the waters surrounding North Uist, while the peat is locally cut. As well as salmon, sea trout, scallops and other shellfish, the smokehouse also produces a salmon smoked using old whisky barrels and finished with a sprinkling of the water of life itself – try it with an oat cake and smear of soft crowdie cheese. The smokehouse can be found on the west side of the island at Clachan.

www.hebrideansmokehouse.com

Meet Finn’s people at North Uist’s ancient sites

There are a number of ancient chambered cairns in the Uists but Barpa Langass is by far the most impressive. A massive pile of stones covers three chambers, thought to have been used for the burial of an important tribe rather than just a select few individuals. Although the narrow entrance can still be made out, recent collapses mean the structure is now too dangerous to enter. While here be sure to walk to the nearby and incredibly atmospheric Pobull Fhinn stone circle. Overlooking Loch Langais, the stones date back at least 3,000 years. The path from the cairn to the stone circle continues past the Langass Lodge Hotel from where it is possible to complete the circuit by heading back up to the main road and turning right.

Listen for the corncrake’s rasp at Balranald

Often heard but rarely seen, the corncrake is a summer visitor to North Uist and the RSPB reserve at Balranald is one of the best places to try and spot this elusive bird. Related to the moorhen and only slightly bigger than a blackbird, the brown, slightly striped corncrake has bright brown wings and long legs and tends to hide in the nettles and flag iris that dot the crofts of North Uist. The RSPB runs evening walks where you are most likely to hear the bird’s unmistakable rasping call or catch a glimpse. Even if you don’t spot a corncrake, Balranald is a fantastic place to walk – follow marker cairns to the most westerly point, the Aird an Runair peninsula.

North Uist, Hut of the Shadows

North Uist, smoking salmon Photo: Hebridean Smokehouse

North Uist, Sanctuary – on the Uist sculpture trail

The Uist Sculpture Trail

Spend a day hunting for these seven sculptures dotted across the island. Commissioned by the Taigh Chearsabhagh museum and arts centre in Lochmaddy, all the artworks interact with the natural environment, including High Tide, Low Tide where the sea slowly draws salt from a dome situated on rocks in the intertidal zone of the shore. This piece and Mosaic Mackerel, a large fish sculpture incorporating mussel and other shells, are close to the arts centre, while the others, including an intriguing camera obscura called Hut of the Shadows, require a bit more exploring to find.

Beachcomb at Clachan Sands

Traigh Hornais ranks amongst the finest of the stunning sandy beaches in the Outer Hebrides. Backed by dunes, the sparkling turquoise waters look tropical on a sunny day – until you dip your toe in the bracing waves. Unless you’re feeling very brave, leave the swimming to the dolphins, seals and the occasional otter that sometimes ride the waves. Access the beach on foot from the Hornais cemetery; bear left at the sands to pass a much older burial ground and eventually reach the headland at the end of the beach where there is a good view to the island of Orasaigh.

Vallay (Bhàlaigh)

Now uninhabited, this tiny tidal island is still farmed as well as being run as a nature reserve by the RSPB, but it was once home to over fifty people. The impressive ruins that dominate the island were once the very grand Vallay House, built in the early twentieth century by the industrialist and amateur archaeologist Erskine Beveridge. After Beveridge’s death in 1920 the house was left to his son, but was later abandoned after he drowned in the waters here in 1944.

Cross the tidal sands to the island (Bhàlaigh)

With bare feet, a keen eye on the tide times and a sense of adventure, the hike over to Vallay is a fabulous experience. Start from Aird Glas just west of Malacleit on North Uist and leave enough time to cross to the far side of the island where there is a sandy beach and headland with the remains of an ancient chapel. Only undertake this at the start of low tide and in fine weather – the water rushes back in extremely quickly and there are deeper, dangerous channels, so leave plenty of time to return safely (and warm up your feet!).

Vallay, crossing the tidal sands

Baleshare (Baile Sear)

Linked to North Uist by a causeway since 1962, Baleshare is a low-lying island so flat it doesn’t even warrant a contour line on the Ordnance Survey’s Landranger map, rising to only twelve metres at its highest point. However it does boast a spectacular white sandy beach backed by dunes. The causeway has helped to preserve the crofting lifestyle here, with around fifty residents continuing a history of habitation stretching back to prehistoric times. Acting as a buffer protecting North Uist from the Atlantic, coastal erosion has eaten away at Baleshare over the centuries, and it is said that until a seventeenth-century storm it was possible at low tide to walk to the Monach Isles fourteen kilometres away.

Monach Isles

This group of islands, also known as Heisker (Heisgeir in Gaelic), lie west from the North Uist coast. The main three islands, Ceann Iar, Shivinish and Ceann Ear, are thought to have once been a single island but the coastal erosion that also took away the land bridge that until the seventeenth century linked the Monachs to Baleshare also separated these islands.

Low-lying and once crofted by over a hundred inhabitants, the islands are now a National Nature Reserve famed for their flower-rich carpet of machair and one of the largest breeding colonies of grey seals in the world. There is a Stevenson lighthouse on the smaller island of Shillay. Getting to the Monachs usually requires your own boat or charter, though Lady Anne Boat Trips based on Grimsay sometimes offers day trips.

Grimsay

Grimsay lies between North Uist and Benbecula, and has been crossed by a road and causeways between these two islands since 1960. Previously it had to be reached either by boat or a hazardous tidal ford.

Learn a traditional craft

Grimsay has long been a centre of traditional boatbuilding and there is a boatyard at Kallin. If you don’t have the time to learn to craft an entire boat, check out the beautiful boat shed and nearby museum. If boatbuilding isn’t your thing, why not master spinning at Uist Wool? Here you can learn about the entire process required to transform sheep’s wool into stylish garments.

Ronay (Rònaigh)

Lying to the east of Grimsay, privately owned Ronay is a rugged island of small, rounded, heather-clad peaks, with a complex, deeply indented coastline. There is a self-catering property available for weekly lets, although you will need to hire a boat to take you across – or kayak or sail there under your own steam. Cleared for sheep farming in the 1820s, the island once had a population of 180.

Left and Right: Bebencula, Rueval summit

Grey seal

Grey seal pup

Benbecula (Beinn na Faoghla)

Lying between North Uist and South Uist, and with a name deriving from ‘pennyland of the fords’ in Gaelic, is Benbecula. Before the causeways which link these islands were built, it would have been necessary to ford the tidal sands between the land masses. Now, as well as the causeways which link to North Uist via Grimsay, and to South Uist, the island has its own airport with direct flights from Glasgow, Stornoway and Barra. The main settlement is Balivanich, which has shops, a post office, a cafe and a small hospital. The annual Eilean Dorcha Festival takes place on the island in July featuring an eclectic mix of traditional music, rock and pop, and even the occasional tribute band.

Reveal the whole island from Rueval (Ruabhal)

Top out on the diminutive summit of Rueval to get a true understanding of the watery moorland landscape of the Dark Island – An t-Eilean Dorcha – as Benbecula is sometimes known. From the island’s highest point at 124 metres an expanse of loch and rock is spread out beneath you. On a clear day the jagged mountains of the Skye Cuillin can be made out across the Minch. It was this thirty-nine-kilometre stretch of water that Flora MacDonald rowed with Bonnie Prince Charlie during his escape after defeat at Culloden in 1746, getting blown ashore at Rosinish, seen to the east from Rueval’s summit. The ascent starts from near a recycling centre on the A865 in the centre of the island, and it forms part of the Hebridean Way long-distance walk.

Know your oats

Oatcakes are a Scottish institution and particularly popular in the Outer Hebrides. The three brothers of Macleans bakery have been producing the savoury biscuits here since 1987, and they are sold widely throughout Scotland. Check out the bakery shop in Uachdar and try one with local crowdie or smoked salmon – but, be warned: oatcakes are very addictive and go well with practically any topping!

Flodaigh (Fladda)

Originally a tidal island, Flodaigh is now linked to Benbecula by a causeway – though this island is a dead end. Its 145 hectares are crofted by a population of around ten, and stepping ashore can feel like stepping back in time by a generation.

Sing with the seals

It’s all about the seals that haul out on rocks and generally hang out in a large sheltered bay on the east of this small island. To reach the seals it’s best to aim for low tide and follow a track on foot to the right after the causeway, heading through a couple of gates and following signs to reach the shore. While grey seals dominate here there are also signs of otters and the patient and keen-eyed may be rewarded with a sighting.

South Uist

More than 1,700 people – known as Deasaich, or ‘southerners’ – live scattered around South Uist. Most of them reside in settlements along the flatter fertile strip of machair on the west which is lined by seemingly endless beaches. To the east is a complete contrast as the island rises to a rugged mountain range.

South Uist is linked to Benbecula in the north – and from there on to North Uist – by a causeway, and also to Eriskay in the south. CalMac ferries run from the main settlement, Lochboisdale, to Mallaig and Oban on the mainland, as well as to the island of Barra. Lochboisdale was a major fishing port during the nineteenth-century herring boom and today has a hotel, a couple of shops, cafe and garage. Accommodation of all types is scattered across the length of South Uist.

South Uist, Hecla and Beinn Corrodale, from Beinn Mhor

Fish finger food

Hot-smoked salmon is a unique taste that should not be missed during a visit to South Uist. Smoked in small batches in traditional hand-built kilns, the flaky salmon has a distinctive and delicious taste quite different from traditional cold-smoked salmon. Located in the north of the island, the Salar smokehouse overlooks the water and the pier where fishing boats tie up – a small shop means you’ll be prepared for a true Hebridean picnic.

www.salarsmokehouse.co.uk

Hang out at Howmore hostel

The Gatliff Hebridean Hostels Trust has converted one of this cluster of thatched blackhouses into a basic, atmospheric hostel. Sited on the machair only a stone’s throw from the sea, the tiny building neighbours the remains of a thirteenth-century monastery. Sleeping sixteen in four dormitories, the friendly hostel is a great way to meet other travellers and is popular with those undertaking the Hebridean Way on foot or by bike.

Raise the Saltire at Flora MacDonald’s house

Flora MacDonald was born nearby and was brought up at the spot marked by this ruin and memorial. While only the parts of the cottage walls remain, the large memorial erected by Clan MacDonald and the wide sweeping views make this an atmospheric pilgrimage to the Jacobite cause. Flora herself was rather a reluctant activist, persuaded by friends to aid the Stuart heir. She helped Bonnie Prince Charlie – dressed as her maid – escape to Skye from Uist in a rowing boat following his defeat at the Battle of Culloden in 1746, a feat later immortalised in the Skye Boat Song.

South Uist, Howmore blackhouses

Climb Beinn Mhor

The ascent of South Uist’s highest mountain is a serious hillwalking challenge requiring a full day and competent navigation skills. Start from the A865 just north of Loch Dobhrain and take the track used to access the peat cuttings heading directly for three distant mountains – once beyond this the going is rough and pathless. Beinn Mhor means ‘big mountain’, yet is actually only 620 metres above sea level. The summit is reached along a spectacular ridge and is blessed with fantastic views. Enthusiastic hillwalkers often combine the ascent with Hecla and Beinn Corradail to make a Hebridean classic.

Play a round on Tom Morris’s course at Askernish

Originally created in 1891 by the father of modern golf, Old Tom Morris, this ‘lost’ eighteen-hole course was brought back to life in 2008. Now you can experience traditional links golf with a round at Askernish Golf Club – look out for the corncrake on the club’s logo. Ecological management techniques, including a ban on herbicides, have helped protect the fragile machair environment, and the continued use of the course for cattle and sheep grazing in the winter has earned the club the moniker ‘the most natural golf course in the world’. Clubs and trolleys are available for hire.

Take in a roundhouse at Cladh Hallan

A short walk near Dalabrog brings you to the remains of three large early Bronze Age roundhouses. The sunken circles and remains of the stone walls can be clearly seen. It is thought people lived in these dwellings between 1100 BC and AD 200, making them rank amongst the longest inhabited prehistoric houses in the world. Several burials have been excavated here including a mummified man and woman. It is possible to make a longer circular walk by heading on to the spectacular sandy beach and returning via the machair.

South Uist, pony at Loch Druidibeg

Walk on water at Loch Druidibeg

Paths including sections of boardwalk enable you to explore this watery landscape. A circular walk taking in four lochs and the contrasting sandy coastal machair gives the best chance of seeing the wide range of birdlife and the free-roaming ponies living here. Designated a National Nature Reserve, this rare habitat is now managed by local community organisation Stòras Uibhist, owners of a large part of the island following one of the first large-scale community buyouts of land in Scotland. Stòras Uibhist also owns Eriskay to the south, and parts of Benbecula.

Bag a remote bothy at Uisinis

Considered one of the most remote bothies in Scotland, Uisinis is an open shelter for walkers, nestled against the mountain of Hecla behind and overlooking the sea. Maintained by the Mountain Bothies Association, this simple shelter, furnished with a stove, sleeping platform and a couple of chairs, provides a real get-away-from-it-all retreat. Take all your own gear – including fuel, unless you are going to take a chance on finding driftwood on the pebbly shore.

Catch a mobile movie at the Screen Machine

With the nearest cinema in faraway Stornoway, a night at the movies in this part of the Outer Hebrides may feel unlikely. However, every ten weeks or so, the eighteen-wheeled truck that is the Screen Machine mobile cinema rocks up on South Uist and in many other places around the Highlands and Islands. The sides of the wagon slide out to reveal an eighty-seater cinema which shows the latest releases, although you do have to bring your own popcorn. Watch out for posters showing where it will be next, or book online: www.screenmachine.co.uk

Eriskay, from the slopes of Beinn Sciathan

Eriskay

Lying offshore from South Uist but connected by a causeway, Eriskay is a real gem. Traditionally a crofting and fishing community, tourism now bolsters the economy although a number of fishing boats still run out of Acarseid Mhòr on the sheltered east side of the island. Just under 150 people live here, and there is a supermarket, cafe, pub which serves food, a bed and breakfast and a couple of self-catering cottages. Locals took control of the island when it was part of a larger community buyout by Stòras Uibhist in 2006.

Eriskay is linked to South Uist by a causeway, the last one to be built in the Outer Hebrides and opened in 2001. Since then the island has become the main CalMac vehicle ferry link connecting the Uists to Barra – a forty-minute journey south from Eriskay.

Climb to the highest point for 360-degree views

The hike to the 186-metre summit of Ben Scrien (Beinn Sciathan) may be short but it’s also very rough, pathless and steep. The reward is a fabulous all-round view of Eriskay and its neighbours. Although other walkers are rare, you are likely to encounter Eriskay ponies, a hardy breed endemic to the Hebrides with a thick waterproof coat – something you are also likely to find useful here.

Sample Whisky Galore

Am Politician is the place for a dram and a tale. Just offshore from here the SS Politician floundered and ran aground in rough seas in 1941. Locals rushed out in boats to liberate, or rescue, the cargo which included a large number of whisky bottles, many of which were secreted away across the island. The episode was immortalised – and exaggerated – in Compton Mackenzie’s Whisky Galore, which was later made into a successful Ealing comedy (recently remade). Today you can see one of the original bottles, with some of its whisky still inside, behind the bar of Am Politician.

Visit Bonnie Prince Charlie’s beach

This stunning strip of white sand just north of the ferry terminal is the place where Bonnie Prince Charlie first set foot on Scottish soil. Arriving from France in July 1745 he received scant support initially from local clans, soon moving on to the mainland where he raised his standard at Glenfinnan and began the Jacobite rebellion. Today the beach is named Coilleag a’Phrionnsa, meaning the ‘prince’s cockleshell strand’; you’ll often have it to yourself. Check out the sandy ground at the back of the beach for the low-growing white and pink flower, sea bindweed – the only place it is found in the Outer Hebrides. It is said that it grows here because seeds fell from the Young Pretender’s pockets as he came ashore.

Barra

On a fine summer’s day there are few islands that can compete with Barra for its sheer beauty, with steep hills, machair rich in wild flowers, and perfect beaches. Together with its neighbour Vatersay – to which it is linked by a causeway – it is home to just over a thousand people. Most of the facilities are centred around Castlebay, which has a shop, cafe/bistro, hotels and a hostel. There’s also a hotel by Halaman Bay. Tourism is now a major contributor to the island economy, although fishing and fish processing remain important, together with crofting.

Barra can be reached by a long CalMac ferry ride from Oban on the mainland, or a shorter run from either Eriskay or Lochboisdale on South Uist. Regular flights from Glasgow touch down on the beach runaway, providing an unforgettable approach to the island. There is a good bus service which trundles around the circular main road on Barra and also across the causeway to Vatersay.

Barra, Castlebay

Barra, Castle Kisimul

Barra, taking off from the cockle strand

Look over the shoulder of Our Lady of the Sea

Barra, like South Uist, is predominantly Catholic – a contrast to the strong Protestant tradition on Harris and Lewis at the opposite end of the island chain. The large white statue of Madonna and Child stands on the flanks of the island’s highest peak, Heaval, and provides an aerial view of Castlebay directly below. Erected in 1954, the best way to reach it is to take the main island road north-east from Castlebay to a parking area at the shoulder of the hill. From here a rough path makes the extremely steep but grassy ascent. Having already climbed to the statue you may as well continue up the steep slopes to the summit of Heaval; the 360-degree views of the island and encircling ocean are awe-inspiring on a clear day. The steep slopes also play host to a gruelling annual hill race where competitors are free to take any route up and down.

Take a boat to the castle

If arriving at Castlebay by ferry, Kisimul Castle is the first thing to catch your eye as the boat approaches the island. Perched on a tiny rocky skerry in the middle of the bay it couldn’t have a better strategic position. A visit starts with a short boat trip before you step ashore to explore the stronghold of the chief of the MacNeil clan who ruled Barra. Built in the 1400s the castle has been restored and includes an impressive feasting hall, chapel and watchman’s house. Don’t miss the climb to the top of the three-storey tower for a unique view of Castlebay, backed by the steep slopes of Heaval.

Complete the Barrathon

Barra’s half marathon takes place each June or July and follows the main road around the island which conveniently clocks in at exactly half-marathon distance. Heading clockwise from Castlebay, the runners are soon heading uphill on a course that quickly weeds out the serious club runners from the so-called ‘fun’ runners. The mix of undulating course and unpredictable, often windy weather means completing this run earns the respect of anyone on the Scottish running scene. Remember to keep enough stamina for the legendary amounts of fine homebaking provided by the locals, not to mention the post-race ceilidh which has been known to go on well into the wee hours.

Spice up the seafood at Cafe Kisimul

Named for the castle it overlooks, this tiny cafe-cum-bistro on Castlebay’s main street packs a hefty punch. Indian and Italian food is given a Barra-style makeover with the emphasis on incorporating as much local fish and seafood as possible. Check out the scallop pakoras or Barra lamb balti. www.cafekisimul.co.uk

Barra, machair at Halaman Bay

Cycle the roller-coaster road

The circuit of the island by bike makes for a perfect day out on two wheels. It may be short but be warned – there are very few flat sections! If time allows, detour to the most northerly point passing the beachside airport at Tràigh Mhòr on the way. Compton Mackenzie – the author of Whisky Galore and The Monarch of the Glen – was a devoted islandphile. He lived for some time on Barra and campaigned to try and ensure the island economy and community was sustainable for the future. Stop off at the tranquil Eoligarry cemetery overlooking the Eriskay ferry jetty to pay your respects. Detouring south to explore the fabulous beaches on Vatersay is also worthwhile if you have anything left in your legs. Bike hire is available in Castlebay.

Make a landing on the cockle strand

While cruising past Kisimul Castle on the CalMac ferry is a pretty dramatic arrival, nothing can beat the adrenaline rush produced from a landing on the beach runway that serves as Barra’s airport. Flight times are dependent on the tide and warning flags show the area that whelk collectors, tourists and seaweed-browsing sheep need to keep clear of. The terminal building may well be one of the least stressful airports in the world – going airside means walking round the back, and to approach the plane simply stroll over the beach. The cafe here is open to all.

Picnic on Barra-dise beach

There’s no shortage of stunning sandy beaches on Barra but Halaman Bay may just come top of the pile. Located near Tangasdale on the west coast of the island it is backed by flowering machair and dunes. Bike or bus the three kilometres from Castlebay, or take a longer hike around the coast to the site of an ancient fort at Dun Ban before returning to watch the waves from the pristine sands.

Vatersay

Linked to Barra by a 200-metre causeway opened in 1991, Vatersay lays claim to being both the most southerly inhabited island in the Outer Hebrides and the most westerly inhabited place in Scotland. Almost divided in two, the island narrows to a dune and sandy beach-lined isthmus; the community hall serves as a popular cafe here in the summer months. Most people live in the south of the island in Vatersay village which boasts a tiny post office.

Discover the Vatersay Raiders

In 1908 a group of men from Barra and Mingulay were imprisoned following a high-profile court case held in Edinburgh. Their crime had been to seize small areas of land and build huts on Vatersay to try and scratch a living, having been impoverished by overcrowded conditions, disease and the effect of absentee landlords using the island as a source of income. These were cottars who held no land of their own and were therefore at the bottom of the pile. The public sympathy aroused allowed the raiders to continue living on Vatersay on their release. Seek out the ruins of their houses at Eorisdale on a walk around the southern half of the island.

Beware the Vatersay Boys

Hailing from Vatersay and Barra and with two great-grandsons of the Vatersay Raiders in the five-piece line-up, the Vatersay Boys are an energetic band that has taken the traditional Celtic music scene by storm. Despite playing sell-out tours and festivals they can still often be found playing at the Castlebay Bar on Barra, or at Vatersay hall’s regular summer weekend ceilidhs. Featuring accordions, pipes, guitar, whistles and driving drums, this is real local music to dance and stomp your feet to.

Fuday

This small island sits between Barra and Eriskay. Now uninhabited, there is evidence of early Norse settlement and records show that before 1901 it supported up to seven people. The island is currently used for summer grazing; traditionally cattle swam the mile-wide strait from Barra. It is said that the first herd of cattle to be put to the summer pasture died of dehydration as they had not been led to the only freshwater source on the island, an inland lochan, and despite the island being only 232 hectares they failed to locate it. Fuday boasts a couple of sandy beaches, one backed by dunes, and a tiny hilltop eighty-nine metres above the sea.

Bishop’s Isles (Barra)

The five main islands lying south-east and south of Barra are known as the Bishop’s Isles and comprise Maol Dòmhnaich, Sandray, Pabbay, Mingulay and Berneray. They are prized for their birdlife and are gaining popularity with hill baggers (there are several Marilyns) and those seeking a connection with the people that used to inhabit the islands. There are a number of boat operators on Barra who will organise bespoke trips – it is possible to land on all five on a single calm, summer’s day, but they also lend themselves to self-sufficient camping stays or day trips.

South of Vatersay, Sandray (Sanndraigh) is a small rocky island boasting cliffs, sea caves and sandy beaches. The last residents left in 1934 and it is now home to a large seabird population. Kayakers can land on one of two sandy beaches.

Together with its southern neighbours Mingulay and Berneray, uninhabited Pabbay (Pabaigh) was bought by the National Trust for Scotland in 2000. The island was evacuated in 1912 after a storm had drowned half the ten-strong male population during a fishing trip in 1897. A bucket-list destination for serious climbers, the cliffs of Lewisian gneiss are regarded as amongst the very best sea cliff climbing venues in Britain. The beautiful and challenging Great Arch includes the fabulously named routes Prophecy of Drowning and Child of the Sea. The first ascents here were by a team that included Chris Bonington and Mick Fowler in 1993. There are only a couple of safe landing sites on Pabbay, which is separated from its immediate neighbours by dangerous tidal flows; a couple of operators on Barra offer boat charter.

Mingulay (Miùghlaigh) attracts the most visitors, a mix of naturalists, hill and island baggers and climbers, but it still remains a lonely and difficult place to reach. A couple of boat operators from Barra are licensed to land on the NTS-owned island but the weather means trips often have to be cancelled at the last minute. The remains of the settlements and burial ground, impressive sea stacks and cliffs teeming with seabirds, rare fauna, and a real sense of isolation make a trip to Mingulay memorable. The island has been uninhabited since it was evacuated at the islanders’ request in 1912. Climb to the summit of Carnan at 273 metres for a 360-degree view of the island and neighbouring Berneray.

Also known as Barra Head, Berneray is an exposed island with huge sea cliffs and is the most southerly of the entire Outer Hebridean chain. Most visitors will want to bag the island by climbing to the dramatic clifftop high point of Sotan. A remote community made a living from fishing and crofting until the start of the twentieth century, when only the lighthouse keepers remained. They too left when the Stevenson lighthouse at the far west of the island was fully automated in 1980. If visiting the lighthouse check out the poignant keepers’ graveyard nearby. It includes the grave of a two-year-old who died of croup and also a lighthouse inspector who died while visiting the island.