Westray, Mae Sands

Overview map

Mainland

The largest island in Orkney is known simply as Mainland. Centrally situated, it is also the hub for transport and services throughout these islands. With an area of 523 square kilometres and an irregular shape with a number of large bays and indented sea lochs, it can take time to really explore Mainland.

Kirkwall is the administrative capital. It has an abundance of historic streets as well as modern services and ferries to many of the northern islands. The island’s airport is a short distance to the east. Many visitors arrive in the southern hub of Stromness where the Hamnavoe, the large roll-on roll-off ferry from Scrabster near Thurso on the Scottish mainland, lands. Being fairly close to many prehistoric sites, Stromness also makes a good base from which to explore the island. The bus service is relatively good, so with a bit of pre-planning and plenty of time it is possible to bag the island using public transport. If visiting with a bike, bear in mind that Orkney as a whole can be very windy and pedalling into a headwind requires stamina. Mainland, Lamb Holm, Burray and South Ronaldsay are linked by causeways – the latter is served by a vehicle ferry to Gills Bay near John o’Groats.

Descend into Wideford Hill cairn

Some of the most memorable prehistoric sites are those that you can just stumble across with no swish visitor centre or latte-hawking cafe. One of the best on Orkney is within walking distance of Kirkwall. Starting from the Pickaquoy Centre follow Muddisdale Road and then a path to climb Wideford Hill. Fine though the view from the summit is, the real objective lies part way down the far side. Here a sliding trapdoor leads to a ladder accessing a large burial cairn dating back to 3000 BC. You can use the torch provided to explore the interior, where ancient Orcadian farmers were once laid to rest. Never busy, it’s likely you’ll have the cairn to yourself so you can practise your Neil Oliver or Alice Roberts impressions in peace.

Take the tour at St Magnus Cathedral

Known as the ‘Light in the North’, this beautiful red sandstone cathedral was founded in 1137. Dedicated to St Magnus, who was martyred on the island of Egilsay, this great building takes your breath away as you enter and glance upwards to the high vaulted ceiling. To get up there and discover the small, high-level walkways, the clock mechanism and the huge bells, you’ll need to book on to one of the tours that run two days a week. Squeeze up the narrow spiral stone staircase, creep along the upper levels and see the cathedral interior in a whole new light. Don’t forget to climb the tower for a bird’s-eye view of Kirkwall.

Witness the Ba’

Twice a year the narrow streets of Kirkwall’s old town are transformed into a heaving mass of players as the ‘Uppies’ from the top of the town struggle with the ‘Doonies’ for control of the ball. The huge scrum can number 350 people with games sometimes lasting several hours. The Doonies’ goal is the sea of Kirkwall Bay and the Uppies must round the Lang corner where the old town gates used to be. Played on Christmas and New Year’s days, the ‘no rules’ game is strictly for Orcadians but makes a great spectacle for visitors.

Try a beremeal bannock

Bere is an ancient form of barley which was once the main crop on the island, able to withstand the cool climate and short growing season. It’s now rare but Barony Mill near Birsay still grinds bere and you can buy a bag of the flour to try making your own bannock. Once a staple for Orcadians, the bannock is a tasty, thick flatbread traditionally cooked on a flat metal griddle over an open fire. Due to the low summer daylight, climate and poor soil, beremeal has always been a low yielding crop and gave rise to the phrase ‘beremeal marriage’ – a marriage that would not bring any wealth with it.

Mainland, Kitchener Memorial on Marwick Head

Mainland, Skara Brae

Mainland, Kirkwall Cathedral

Mainland, sea stack at Yesnaby

Mainland, chambered cairn on Wideford Hill

Mainland, Kirkwall Cathedral

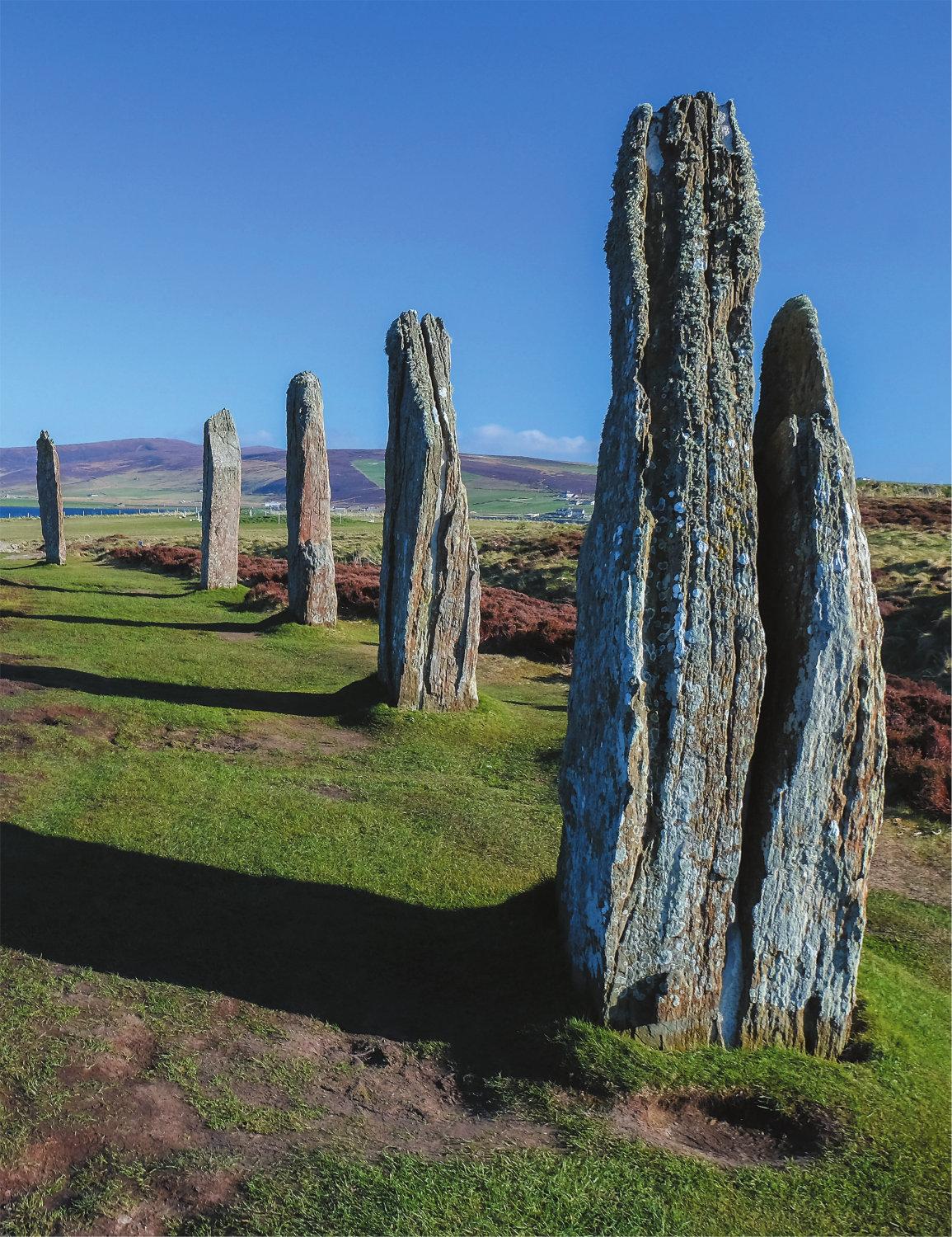

Experience the Ring of Brodgar

While we tend to think of Orkney as wild and remote, archaeologists have long argued that it may once have been the epicentre of life in Britain – the place to be in Neolithic times. Nowhere is this more apparent than the Ness of Brodgar. Home to Scotland’s largest stone circle, walking around the twenty-seven stones which are still standing is an experience not to be missed. When built around 5,000 years ago there were around sixty stones.

Towards Stenness a large area has been a hive of archaeological activity in the summer months for many years, and the dig has so far revealed the remains of numerous buildings including a Neolithic temple. There is evidence that before the complex was closed down around 2200 BC, the ceremonial slaughter of over 400 head of cattle and a huge feast were held, the purpose of which remain a mystery. Equally mysterious are the enormous Stones of Stenness just along the road, where four great monoliths tower over six metres high and were once part of another large stone circle. A sense of great antiquity doesn’t get any more palpable than here.

Check out the fitted furniture at the 5,000-year-old houses at Skara Brae

One of the best-preserved Neolithic sites in Europe, Skara Brae was a bustling village well before Stonehenge was built. A huge storm in 1850 uncovered some of the coastal remains and today you can explore nine houses, incredibly some of them still with their stone-built box beds, shelves and furniture. The visitor centre includes a full replica house as well as the obligatory audio-visual presentation, helping to make sense of what you can see on the ground. The setting immediately above the beach adds to the magic. Entry to the nearby seventeenth-century mansion Skaill House is included in the Skara Brae entrance charge.

Walk the west side

This challenging thirty-one-kilometre hike along Mainland’s west coast takes in a wealth of stunning scenery, historic sites and wildlife-watching spots. It can be split into sections, or the very fit could hike the lot on a long summer’s day. Starting from Stromness the route soon leaves civilisation behind as it rounds the southern tip of Mainland and climbs to the great cliffs of the west coast. The route passes an array of sea stacks including the dramatic two-legged Yesnaby Castle, popular with climbers. Further north it takes in an ancient broch and descends to the Neolithic village of Skara Brae. The next section climbs again along fabulous clifftops to reach the Kitchener Memorial. The tower commemorates the 588 men, including Lord Kitchener, who lost their lives when the HMS Hampshire hit a mine and sank just offshore here in 1916. The walk finishes at the imposing ruins of the Earl’s Palace in Birsay.

Decipher the Viking graffiti at Maeshowe

Access to Maeshowe, the largest and most mysterious Neolithic tomb on Orkney, is understandably restricted to tours which must be booked in advance. At the appointed time you’ll find yourself in a small group, crouched almost on all fours as you negotiate the eleven-metre-long entrance tunnel, the sides of which are, incredibly, single massive slabs. Once the heart of the tomb is reached you can stand comfortably and the exquisite craftsmanship of the people who built the tomb becomes immediately apparent. Flagstones taper inwards forming the beehive-shaped roof of the large central chamber, built over 5,000 years ago. The tomb was discovered and raided by Vikings who left their own marks in the form of runic graffiti. After much painstaking work, historians have managed to translate these thirty early messages, including the highest one which merely boasts that Tholfir Kolbeinsson carved these runes high up – it seems human nature never changes!

Dive into Scapa Flow

Following the First World War armistice the German fleet was held at Scapa Flow while the fate of the ships was negotiated. Fearing the loss of the ships and honour, the German commander ordered the ships to be scuttled in June 1919. Over fifty ships were sunk in the Flow and although many were later salvaged for scrap, a number remain and have become popular dive sites. A number of dive boats operate in the Flow, including two with dive shops in Stromness. One of them offers a half-day dive for complete beginners.

If diving doesn’t rock your boat or you need to warm up after a dip in the cold waters of the Flow, a dram of Scapa whisky may be just the tipple. Distilled on the shores of the Flow, Scapa is one of two distilleries on Mainland Orkney, the other being Highland Park.

Follow the ancient path on to the Brough of Deerness

The Brough of Deerness is a massive lump of rocky ground detached from the rest of the Deerness peninsula and jutting out into the North Sea. With thirty-metre vertical cliffs on all sides, getting to the top is a bit of a challenge. First you must descend steep steps into Little Burrageo and then climb the narrow, sloping path to the top. Here are the remains of a settlement which once surrounded a tenth-century chapel, although recent excavations have suggested the ruins are from the Viking era. It’s worth continuing around the coast along the high cliffs to Mull Head; the area is a nature reserve.

Step out to an Orcadian Strip the Willow

The traditional music scene is alive and fiddling across Orkney and the best way to experience it is to join a local ceilidh. These can range from semi-formal concerts with a variety of musicians, to dances with a traditional band and a break for homebaking and the ubiquitous raffle. Check out community noticeboards for venues. One of the simplest but most popular ceilidh dances has to be Orcadian Strip the Willow where two lines of men and women face each other and the top couple ‘strip’ the willow by dancing with their partner alternately with everyone else in the line. If dancing isn’t your thing, try and catch a music session at The Reel next to St Magnus Cathedral in Kirkwall where some of the best Orcadian musicians play.

Mainland, Maes Howe

Mainland, path on Brough of Deerness

Mainland, Brough of Deerness

Mainland, Stromness

Brough of Birsay, kirk ruins

Brough of Birsay, causeway

Lamb Holm, Churchill Barrier

Brough of Birsay

This tidal island is a must not just for island baggers but for anyone with a taste for history or a love of puffins. Situated at the far north-west of Mainland, the causeway across is only exposed for a couple of hours either side of low tide, so visits need to be planned carefully.

Cross to the Brough

From Point of Buckquoy it’s fun to cross the concrete walkway that appears to float over the receding waters of the Sound of Birsay to reach this uninhabited island. Evidence of previous residents is soon on show as the round-island walk passes the remains of a Norse settlement and twelfth-century church. The island’s lighthouse is only 11 metres tall, taking advantage of its position perched on the cliffs of Brough Head. These cliffs are also home to numerous seabirds including puffins in the summer. It’s possible to make a complete circuit of the cliffs, hopefully with plenty of time to beat the incoming tide.

Lamb Holm

Linked from Mainland Orkney by the first Churchill Barrier – the second and third provide the onward road link to tiny Glimps Holm and then Burray – Lamb Holm is a small uninhabited island that most visitors would whizz across unnoticed were it not for the lasting legacy of Second World War POW Camp 60.

Marvel at the Italian Chapel

Over 500 Italian prisoners of war were housed at Camp 60 on Lamb Holm and used as labour for building the causeways linking the islands and preventing sea access to Scapa Flow. Having been captured in North Africa and transported to Orkney the climate must have been quite a shock to these men. To assist with camp order and morale, the POWs were allowed to transform two Nissen huts into a chapel. Using concrete and plaster, the beautifully ornate facade and interior, including painted frescoes and carvings, were crafted under the direction of Domenico Chiocchetti, who returned twice to Orkney after the war. Today the chapel operates as a poignant visitor attraction.

Burray

Lying between Mainland Orkney and South Ronaldsay, life on Burray changed forever when the causeways were built towards the end of the Second World War, ending the isolation of these southern islands. Burray Village has a shop, school and hotel, and the island has a fascinating museum housing a large fossil collection. Burray is home to around 350 people.

Cross the Churchill Barriers

Home to the British naval fleet during much the Second World War, Scapa Flow had to be heavily defended. The main entrances to this huge natural harbour were obstructed by sunken blockships, anti-submarine nets and mines, all backed up by land-based lookouts and artillery. Despite these efforts, a German U-boat slunk into the Flow just north of Burray during high tide in October 1939. It sunk HMS Royal Oak with the loss of 833 men. Following these terrible losses Winston Churchill ordered the construction of permanent barriers.

The barriers were built primarily by 1,200 prisoners of war based in camps on Burray and Lamb Holm. The use of POWs for war work is prohibited by the Geneva Conventions but the British have always argued that the work was for improving communications and certainly that has been the benefit for modern-day Orcadians. There are four barriers, the first linking Mainland Orkney with Lamb Holm, the next links to Glimps Holm, then Burray, and finally Barrier 4 continues to South Ronaldsay. Cross them all and you will also see some of the original blockships projecting from the water.

Hunda

Constructed during the Second World War, possibly as a practice run for the Churchill Barriers built to block German U-boat access to the British naval fleet, the causeway to Hunda means it’s easy to access this delightful small island. A mere 100 hectares in size, the island is uninhabited and currently used for sheep grazing – its name comes from the Norse for ‘dog island’.

Cross the causeway to Hunda

The 500-metre-long stone and concrete causeway offers a grand approach to Hunda. The island itself is easily walked around in half a day – there is a clear path, excellent views, plenty of birdlife and the chance to spot otters, seals and passing porpoises. There’s no parking at Littlequoy so it’s best to walk in along the track from Burray Village, eventually making for the coast before the crossing of the causeway at Hunda Reef.

South Ronaldsay

South Ronaldsay is the fourth largest of the Orkney islands with just under 5,000 hectares of relatively fertile land. It is surrounded by a hugely indented coastline boasting a variety of cliffs, arches and caves, and sandy beaches. The large vehicle ferry, the Pentalina, is a catamaran and runs from Gills Bay on the Scottish mainland to St Margaret’s Hope, while the John o’Groats passenger ferry disgorges a large number of visitors on to coach tours as well as cyclists and others at Burwick at the southern end of the island. Most services are found in St Margaret’s Hope, although there are eating and accommodation options throughout the island.

Get off your trolley in the Tomb of the Eagles

Numerous well-preserved Neolithic tombs are dotted around Orkney, but this is the only one usually entered by lying on your back – visitors haul themselves through the entrance on a small, wheeled trolley, though knee pads are provided for those who prefer to crawl! Once inside, this coastal cairn reveals several chambers including one where farmer Ronnie Simison discovered 30 human skulls after stumbling across the site in 1958. Still in family hands, the cairn and museum are surprisingly hands-on with visitors encouraged to handle some of the finds and chat to Ronnie’s two enthusiastic and knowledgeable daughters. The tomb is named after the large number of eagle talons discovered during the excavations; it is likely that the birds had a symbolic significance for the people who lived and were buried here 5,000 years ago.

Clear your head at Hoxa

Hoxa Head is one of the best places to explore wartime defences and get a feeling for how central Orkney was for Britain’s naval fleet during both world wars. From a small parking area a path leads around to Hoxa Head, offering great views over the spectacular natural harbour that is Scapa Flow. Along the way you’ll find the remains of a large number of gun batteries, bunkers and a small lighthouse used to defend the narrow Sound of Hoxa that lies between here and the island of Flotta. Huge underwater nets, as well as mines activated from the shore, were hung across to Stanger Head on Flotta to try and prevent German U-boats accessing the anchorage during both world wars. Now home to grazing sheep and seabirds, it is worth continuing around the coast to pass three deep inlets – known as geos – in the cliffs before returning past the site of a military camp to the start of the walk near The Bu.

Hike the east coast

This challenging half-day walk is the best opportunity to get a real taste for South Ronaldsay’s coastline: a mix of low and high cliffs, many with impressive flagstone strata; deep sea inlets or geos; and a gloup, a collapsed cave which now acts as a blowhole in stormy weather. Start from Burwick near the pier for the John o’Groats ferry and head south initially to round Brough Ness before the coast curves to the north. The walk diverts inland to pass the visitor centre for the Tomb of the Eagles chambered cairn, and the tomb itself is passed another 1.5 kilometres further along the coast. Look out for peregrine falcons at Mouster Head before the walk reaches its final stage crossing the wide sandy arc of Newark Bay to reach one of Orkney’s oldest parish churches, St Peter’s Kirk. From here you would need to have arranged transport or it’s a three-kilometre walk on quiet roads to St Margaret’s Hope.

South Ronaldsay, Tomb of the Eagles

Hoy

Hoy is the second largest of the Orkney islands, and its name comes from the Norse word haey meaning ‘high’ – a reference to Hoy’s great hills and cliffs. A car ferry from Houton on Orkney Mainland links to Lyness at the southern end of Hoy, or to Longhope on neighbouring South Walls which is linked by a causeway. There’s also a useful passenger ferry service from Stromness which lands at Moaness in north Hoy (usually via Graemsay).

Most facilities and shops are found in the south of the island including hotel, pub and bed and breakfast accommodation. There is a cafe and hostel at Moaness and another tiny hostel at Rackwick.

Visit the Old Man of Hoy

First climbed in 1966, this iconic pillar of red sandstone is a must-see for every visitor to Hoy. None of the climbing routes on this 137-metre sea stack are graded less than Extremely Severe, and reaching the base involves a potentially dangerous rope traverse. But even if you’ll never get up there to add your name to the logbook stored in a box in the summit cairn, reaching the clifftops opposite on Hoy’s dramatic coast is good enough for most island baggers. The shortest approach is from Rackwick Bay, just over a nine-kilometre round trip on a clear track and path. If you don’t have a car on Hoy then you can walk from Moaness to Rackwick through the Rackwick Glen, another seven kilometres each way.

Squeeze inside the Dwarfie Stane

It’s not often you get to crawl inside a prehistoric carved boulder. The Dwarfie Stane, a Neolithic rock-cut tomb, can be found not far from the road to Rackwick in the glaciated valley below Ward Hill. Hollowed out from a single block of stone using primitive tools before metal had been discovered, the entrance leads to two side chambers, each just long enough to hold a body (or two) and featuring a rougher ‘pillow’. The original stone slab which sealed the entrance sits on the ground outside. Local legend suggests a giant and his wife originally lived in the Stane and were imprisoned in it by a third giant who wanted to rule Hoy. The captors are said to have gnawed their way out through the roof, neatly explaining the hole which is presumed to have been made by grave robbers and has been there since the sixteenth century.

Experience a bonxie bombing

Hoy is home to the second largest colony of great skuas in Britain. Known locally as bonxies, these large birds have a grace and speed of movement in the air, lacking when on the ground. These ‘pirates of the sea’ harry other seabirds until they drop their catch, at which point the skuas help themselves to the still-warm takeaway. They will also take eggs and young chicks from nests in cliffs, as well as dive-bomb unsuspecting walkers who get too close to this ground-nesting bird during the breeding season. The best place to see them on Hoy is on the wide plateau of Cuilags, most easily accessed via the ridge facing the Moaness Pier ferry. Hillwalkers with the energy and time can extend the walk over the Sui Fea plateau before heading to the immense cliffs of St John’s Head. The coastal cliffs can then be followed southwards to the Old Man of Hoy and on to Rackwick Bay.

Hoy, Scad Head

Hoy, Berriedale Wood

Hoy, Dwarfie Stane

Hoy, Ward Hill

Hoy, battery at Scad Head

Discover Orkney’s native woodland

Lying deep in Rackwick Glen, Berriedale Wood is thought to be a remnant of the type of woodland that would have covered most of Orkney and Shetland around 7,000 years ago. Today it is an important habitat for other wildlife making a home amongst its downy birch, hazel, rowan, aspen, willow and roses. Find it nestled in a deep gully on the west side of Rackwick Glen about two and half kilometres from Rackwick. Those keen to spot more wildlife should keep their eyes peeled for white-tailed eagles – a pair has nested on crags above the Dwarfie Stane and successfully hatched a chick for the first time in 2018. The sheer size of these birds, with a wing span of well over two metres, makes them hard to miss.

Survey all Orkney from Ward Hill

It is said that from the summit of Ward Hill, the highest point on Hoy and indeed all Orkney, all the islands except one – Rysa Little – can be seen. You’d certainly need to be blessed with good weather, but the ascent is worth it for the views of Scapa Flow and Hoy alone. All ascent routes are very steep. One option is to head up from the road near the Dwarfie Stane – your calf muscles will be screaming on the unrelenting turf-clutching ascent. The summit of Haist (333 metres) is visited en route to the main summit of Ward Hill, the highest point in Orkney at 479 metres. It is possible to descend to the bealach between it and Cuilags before returning past Sandy Loch.

Search for the searchlights at Scad Head

No trip to Hoy is complete without visiting some of the sites associated with the island’s prominent role in the Second World War. Over 12,000 military personnel were stationed on Hoy during the war, mostly at Lyness, dwarfing the island’s small population. The Scapa Flow Visitor Centre is a great place to learn more and explore the remaining building which includes the Navy, Army and Air Force Institutes (NAAFI) recreation centre where over 1,900 used the cinema, dance hall and leisure facilities a week. There are also air raid shelters and a naval cemetery. The most atmospheric place to contrast the beautiful peacetime landscape with the wartime reality is at Scad Head. Here the remains of coastal gun emplacements and lookout towers contrast oddly with their surroundings. It’s now simply a surreal place from which to watch the seabirds and seals. Halfway between Lyness and Quoyness, the remains of an old tramway lead down to Scad Head – if time allows you can make a circuit by walking up to the viewpoint on Lyrawa Hill.

South Walls

South Walls is attached by a causeway known as the Ayre to the south-east corner of Hoy. Originally a tidal island, the causeway made access more permanent during the First World War. The island shelters the North Bay and includes the settlement of Longhope where the ferry from Houton and Flotta calls, alternating with stops at Lyness on Hoy.

Climb the Martello Tower at Hackness

The robust circular Martello Tower at the Point of Hackness is one of a pair guarding the Switha Sound between South Walls and Flotta. Built during the Napoleonic Wars to protect a northern trade route to Scandinavia and Baltic ports from French and American attacks, it never saw action. Today you can climb the ladder to the high entrance door and imagine what life was like for those stationed at this remote fortress. Open April to the end of September, the tower is operated by Historic Environment Scotland and there is an entrance charge.

Light your candle on the amazing south coast

The south coast of South Walls boasts an embarrassment of natural sea features. Arches, caves, blowholes and stacks all vie for your attention on the seven-kilometre walk between the Ayre and Cantick Head. Keep a particular eye out for the Axe and the Candle, both prominent sea stacks. The cliffs are home to numerous seabirds and the keen-eyed may spot peregrine falcons as well as Arctic skuas hunting amongst the nesting birds. Look beneath your feet and you might see a purple Scottish primrose which flowers in May and August. The walk finishes with a dramatic approach to Cantick Head lighthouse. It is possible to make a circuit by returning inland to the Ayre via Osmondwall.

Graemsay

Graemsay, a fertile island known as ‘Orkney’s Green Isle’, has a population of around twenty-five.

The passenger ferry to Hoy from Stromness stops at Graemsay and takes only fifteen minutes when going direct, though it often calls first at Hoy, extending the journey time to forty-five minutes. Expect to share the journey with schoolchildren and commuters from both islands.

Highlights and low lights

The best way to see the island is on foot and it’s easy to walk all the way round the island in a day between ferries. Once on Graemsay follow the road towards Hoy High Lighthouse; one of a pair of Stevenson lighthouses on the island, this one is thirty-three metres tall. Continuing on the road, the verge often ablaze with orchids and other wild flowers, pass the community hall and descend to the coast. Rougher walking hugs the coastline, passing the Low Lighthouse (a mere twelve metres tall), a Second World War gun battery. On the foreshore you may find pottery fragments from an 1866 shipwreck which claimed the lives of eleven people. It’s necessary to return to the road for a distance before a final stretch along the south coast offers great views of Hoy. After passing the remote Old Kirk the route returns to the ferry pier having completed a 360-degree tour of the island.

Flotta

Flotta lies at the southern end of Scapa Flow and has a resident population of around eighty, although many more people commute to the island every day to work at the large oil terminal which handles around ten per cent of the UK’s oil. The island also experienced two huge but temporary population explosions during the two world wars. Ferries to Flotta run from Houton on Orkney Mainland, and also from Lyness on Hoy and Longhope on South Walls.

South Walls, coast walk

South Walls, Hackness martello tower

Graemsay, Hoy High lighthouse

Flotta, sculptures

Flotta, the ferry

Flotta, battery overlooking Scapa Flow

Rousay, on Blotchnie Fiold

Rousay, ferry jetty

Rousay, the ferry, Eynhallow

Rousay, Taversoe Tuick chambered cairn

Rousay, broch

See the sea stacks

Sometimes overlooked as a place to visit because of the industrial oil terminal, the rest of Flotta is very quiet and green, with good views over Scapa Flow and to Hoy. However, the highlight has to be Flotta’s sea stacks, closely followed by the quirky scrap metal sculptures dotted about the island. Both can be seen from the fifteen-kilometre trail around the southern half of the island. The cletts, or sea stacks, make for an impressive view from Stanger Head, and both are wider at the top than the bottom. While on the trail see how many of the Flotta-made recycled sculptures you can spot – the three penguins are a favourite.

Rousay

Rousay is a must for any island bagger, offering an amazing range of archaeological sites outside the mainstream tourism circuit of Mainland. This small, hilly island is one of great character, deserving a full exploration. The car ferry runs from Tingwall on Mainland – but be warned if you are taking a vehicle you will have to reverse either on or off. The same ferry also links Egilsay and Wyre to Mainland. Rousay has a primary school and a cafe/pub, and is home to just over 200 people.

Dig in to Rousay’s deep past

A short walk along the coast at Westside leads through thousands of years of history. First up is Midhowe Cairn – a huge chambered burial cairn where human remains were placed in separate stalls within the 4,000-year-old structure. Today a modern building protects the old one from the elements, so that the latter remains as well preserved as when it was first excavated in 1932. Just along the coast is a large and well-preserved Iron Age broch, perched on the water’s edge. You can still see the double-wall construction of this defensive building. For a chance to watch modern-day time-teamers in action, head back along the coast, passing the sixteenth-century St Mary’s Kirk, to reach the site of the archaeological dig at Swandro. Every summer archaeologists and students descend on the site keen to uncover the secrets of the Pictish and Viking buildings before storms and rising sea levels take their toll.

Top out on Blotchnie Fiold

The highest point on Rousay is part of an RSPB reserve, famed for its birds of prey including short-eared owls. The seven-and-a-half-kilometre round trip can easily be done in half a day, leaving plenty of time to clamber inside the 5,000-year-old Taversoe Tuick chambered burial cairn passed on the way up from the ferry pier. The route climbs over heather moorland, following old peat cuttings for a time; it has occasional waymarkers. Climb to the high point of Blotchnie Fiold (250 metres) before another climb to reach the trig point on the lower summit of Knitchen Hill. From here the view is all expansive skies, and the blue sea dotted with green isles. If time allows there is a fascinating heritage centre near the ferry and also a cafe/bar.

Take a Rousay Lap

The undulating road around Rousay is 13.1 miles long, lending itself to the annual half marathon – the Rousay Lap – which takes place in August. Steep in places with two notable hills known locally as the Leeon and Sourin Brae, it’s incredibly scenic. Free to enter, the event is open to cyclists, runners and walkers, and if it’s all too much there’s also a five-kilometre Peedie Lap each June. Even if you can’t take part on the day, the road round Rousay makes for a great half-day cycle ride. A number of detours on foot enable you to visit the brochs and cairns for which the island is famous, and the gardens at Trumland House are also worth a visit. Cycle hire is available from Trumland Organic Farm.

Egilsay

Linked by ferry from Tingwall on Mainland via either Rousay or Wyre, Egilsay is a long thin island with a resident population of around fifteen. Home to the elusive corncrake in the summer, it’s a good place for a quiet wildlife wander or a natter with friendly locals. Its size makes it ideal for a half day’s exploration on foot or by bike. The community hall is open to visitors with an honesty system for hot drinks.

Watch your head at St Magnus Church

The distinctive cylindrical tower of St Magnus Church is unmissable as the ferry draws into Egilsay. An ancient place of pilgrimage, it was here that Magnus was killed by an axe blow to the head. Having shared the Viking kingdom in an uneasy alliance with Earl Haakon, the two rulers arranged a meeting on Egilsay in 1115. On arrival it was obvious that Haakon intended to kill him, having arrived with boatloads of armed men. Magnus led his men to pray in the church, and he was duly executed. Although it featured in the Orkneyinga Saga, what seems like the stuff of legend became more real when a skull with a large crack in it – possibly caused by an axe – was discovered in the walls of St Magnus Cathedral in Kirkwall.

Egilsay, isolated farmstead

Wyre, Cubbie Roo’s castle

Egilsay, St Magnus Church

Wyre

The smallest of the three islands linked by ferry from Tingwall on Mainland, Wyre is reached either via Rousay or Egilsay. Known for the seals which haul out at The Taing at the westernmost point on the island, Wyre also has a heritage centre packed full of fascinating photographs and information about life on the island.

Check out Cubbie Roo’s Castle

Cubbie Roo was a man so massive that according to legend he used many of Orkney’s islands as stepping stones. He is said to have made Wyre his home, and the castle built around 1145 is one of the oldest castles in all Scotland. Most of the stories surrounding Cubbie Roo have him trying to build stone bridges between islands or hurling boulders across the water to their current resting places. One tells that he built a bridge between Wyre and Rousay that collapsed and formed the mound known as Cubbie Roo’s Burden. The castle remains can be found next to the twelfth-century ruins of St Mary’s Chapel – turn right off the main road just before the heritage centre on the way from the ferry.

Westray

The sixth largest and one of the more remote major islands in Orkney, fertile Westray lies over thirty-two kilometres north of Kirkwall and is home to around 600 people. It is served by a vehicle ferry which takes an hour and half to reach Rapness, where it is usually met by a bus. There are also daily flights from Kirkwall. Although most shops and services are centred on the main settlement Pierowall, accommodation is scattered across the island, including hotels, bed and breakfasts, self-catering, a hostel and camping. There are two general stores in Pierowall, one of which also has a cafe. Jack’s Chippy, also in Pierowall, is a takeaway very popular with locals. There is also a well-stocked general store and post office at Skelwick.

Pootle with the puffins at Castle o’Burrian

Westray is the best place in Orkney to see puffins. Many visitors come here especially to see them, and Castle o’Burrian is the place to do it. The Castle is actually a large sea stack, detached from the cliff and with a thick wodge of turf on top for the puffins to make their burrows safe from predators and the blundering feet of birdwatchers. Take the coast path for approximately one and a half kilometres from Rapness Mill at Rack Wick bay in the south of the island and find a comfortable place to sit opposite the Castle and let the show begin; keep a look out just below the path, as many puffins nest right by it too. These colourful and characterful birds spend most of the year at sea, coming ashore from May to July to breed.

Get a head for heights at Noup Head

The seventy-six-metre-high cliffs at Noup Head are the best place to see the masses of seabirds that come to Westray to breed during the spring and early summer. The flagstone cliffs have formed millions of natural ledges which are used by gannets, guillemots and kittiwakes, while the springy turf on top provides a home for puffins and Arctic terns. This is a great place to visit at any time of year as the cliffs and nearby natural arches and caves are spectacular, while the now solar-powered Stevenson lighthouse makes a great focal point. The shape and terracing of the cliffs here provided the inspiration to architect Kengo Kuma for his striking V&A building on Dundee’s waterfront. There’s no public transport but Noup Head is a short cycle ride from Pierowall, or you can drive along the bumpy track to the lighthouse. It’s also possible to make a circular walk from Backarass.

Westray, Castle o’ Burrian

Westray, sunset at Tuquoy

Westray, puffin at Castle o’Burrian

Westray, Mae Sand

Westray, Noup Head

Westray, signpost

Papa Westray, the last great auk

Discover the nousts at Mae Sand

Westray’s eighty-kilometre coastline boasts eighteen sandy beaches and all are worth discovering. Mae Sand is particularly atmospheric – and usually deserted – and you can still see the shelters once used by Vikings to store their boats. Mae Sand can be approached on foot via a rough coastal path from Tuqouy or via the tiny settlement of Langskaill. Search for the boat-shaped drystane-walled depressions at the back of the beach – these are where early Norse settlers would have protected their boats. Known as ‘nousts’, they have been used by Westray folk for generations. The recently built Westray skiff bears a striking resemblance to open boats used right back to Viking times.

Nibble on Westray Wife

The Westray Wife is a 5,000-year-old figurine also known as the ‘Orkney Venus’. Discovered at the Links of Noltland in 2009, it was the first Neolithic carving of a human figure found in Scotland. Only four centimetres tall, the figure consists of a round ‘head’ and square ‘body’. Find it at the Westray Heritage Centre in Pierowall. To really get a taste for Westray life, sample the moreish washed-rind cheese also known as Westray Wife, produced on the island by Wilsons of Westray and available in local shops.

Papa Westray

This remote island, known locally as Papay, sits to the north-east of Westray and can be visited from there either via the world’s shortest scheduled flight, or by passenger ferry from Gill Pier in Pierowall. As well as bed and breakfast and self-catering accommodation, there is a modern hostel at Beltane House close to the community shop. Bicycle hire is available by contacting the Papay ranger (details on Facebook).

Walk the island circuit

Hiking right round the coastline makes for a fantastic day out – take in the high flagstone cliffs, endless sandy beaches, rich farmland and ancient buildings to get a real feel for island life. Start by turning right at Moclett pier and following the coast path past the Bay of Burland. The huge white sands of South Wick offer tantalising views to the tiny Holm of Papa just offshore. Further along, the RSPB North Hill reserve is reached. The cliffs here offer great spots for watching the black guillemots, and further on you may have to defend yourself against aggressive terns who nest on the far side of Mull Head. The west coast of the island is gentler and includes the serene and ancient St Boniface Kirk, and then the impressive and well-preserved Neolithic farmstead the Knap of Howar, said to be the oldest north European dwelling still standing. The circuit of the island finishes by crossing a fine sandy beach, not the worst place to wait for the return ferry.

Find the last great auk

It was on the cliffs of Fowl Craig that the world’s last breeding pair of great auk were killed, causing the extinction of the species within thirty years. Also known as the ‘northern penguin’, these flightless black and white birds stood a metre tall. The male was shot by local man, William Foulis, on the command of a collector in 1813; the female and her egg had been destroyed the previous year. Although excellent swimmers, great auks moved slowly on land and having few natural predators they were not naturally scared of humans. First killed for their meat and feathers, the last birds were shot as specimens for museums and private collections. A small memorial stands on Fowl Craig which today is a great place to spot our surviving species of auks, namely guillemots, razorbills, black guillemots and puffins. Fowl Craig is found on the north-east of the island and can be reached on foot along the coast or by cycling as far as Hundland.

Holm of Papa

The Holm is a small – twenty-one hectares – uninhabited island that sits in South Wick bay just off the east coast of Papa Westray. Known locally as Papay Holm, visits can be arranged by private boat – ask at the Papa Westray community shop. The main attraction is a twenty-metre-long chambered burial cairn known as Southcairn with a characteristically Orcadian stalled structure.

Shapinsay

Shapinsay is a mere twenty-five minutes by ferry from Kirkwall, and as a result many of its 300 or so residents work in Orkney’s capital, commuting by sea. This fertile, low-lying island is mainly given over to farming with a couple of small nature reserves known for waterfowl, waders and Arctic terns. The approach to Shapinsay by ferry is dominated by Balfour Castle. This large Scottish Baronial pile dates back to the 1840s and was originally designed as a so-called ‘calendar house’ comprising fifty-two rooms, twelve exterior doors, seven turrets and 365 panes of glass. It’s a private home, but the former gatehouse near the ferry slipway now houses the island pub. There is also a shop, cafe and heritage centre in the small village of Balfour.

Shapinsay, the douche

Check out the Shapinsay shower

From the harbour it’s a short walk south along the coast to reach a prominent stone tower. Originally built as a dovecote used to breed the birds for meat back in the seventeenth century, it was later converted to use as a saltwater shower by David Balfour as part of his works completing the castle in the 1840s. It’s not possible to enter the tower – known locally as ‘the douche’ – but it can be visited by a brief walk from the ferry pier. It’s possible to continue round the coast to Vasa Loch before heading back to Balfour on quiet lanes.

Eday

Eday is fourteen kilometres long but narrows to a mere 500 metres at one point, giving rise to its name which comes from the Norse for ‘isthmus island’. Today it is linked by daily vehicle ferries from Kirkwall on Mainland which land at Backaland in the south of the island, and by a weekly inter-island flight from Kirkwall. There has been talk of building bridges or causeways to link to nearby Westray. The island has a population of around 160, down from a high of just under a thousand in the early 1800s. There is a heritage centre with cafe, small store, hostel, bed and breakfast and self-catering accommodation, and bike hire.

Journey through time

Eday has a rich array of archaeological sites and the island’s heritage trail means you can explore them all on foot. The route starts at the shop – either use the bus from the ferry or bike or walk – and soon passes the four-and-a-half-metre tall Stone of Setter, one of the tallest standing stones in Orkney. Follow marker posts towards Vinquoy Hill, passing two smaller chambered cairns before reaching Vinquoy chambered cairn, thought to be at least 4,000 years old. The walk then heads past old peat cuttings to reach a trig point on the cliffs at the most northerly point of the island – a wonderful vantage point and a good place to watch the seabirds before the return leg.

Hang out with the seals

Many come to Eday for some peaceful wildlife watching and setting yourself the target of spotting a seal or even an otter or red-throated diver is one way to bag the island. The divers arrive in the summer and can often be seen on Mill Loch where there is a handy hide. If you hear a regular whirring sound it’s likely to be a snipe and you can add that to the wildlife tick list. For seals, head to the very south of the island where they often haul out at the Point of War Ness. Keep an eye out here too for passing dolphins, minke whales and the very occasional orca.

Stronsay

Known as the ‘Island of Bays’ due to its irregular shape indented by three fine beaches, Stronsay is a low-lying island which is home to around 300 people. It is linked to Mainland Orkney via a daily ferry from Kirkwall to Whitehall, sometimes stopping at Eday en route. There are also daily flights on the island hopper from Kirkwall airport. There is a hotel, bed and breakfast, hostel, two cafes, school and two general shops including Ebenezer Stores which also offers free bikes for visitors.

Check out the Vat of Kirbister

Stronsay’s standout feature is a collapsed sea cave with an impressive natural arch spanning the entrance to a gloup, or blowhole. It can be visited as part of a twelve-kilometre circular walk that heads around Lamb Head, starting from the parking area near Kirbuster Farm. The huge rock arch itself is soon reached but the rest of the coastline is no disappointment. A couple of high sea stacks include Tam’s Castle on which a hermit is said to have lived. Nowadays it’s home to a whirling cacophony of fulmars and guillemots. Two more headlands and a number of deep geos keep adding interest to the walk before the final section through farmland leads back to the start.

Search for mermaids at the Sands of Rothiesholm

It’s hard to choose a favourite but the Sands of Rothiesholm just pips St Catherine’s Bay to the post in the battle to be Stronsay’s finest beach. The bright white sands stretch out for over 1,500 metres, and beachcombers can search for the rare woody canoe-bubble shell, a type of sea snail shell found in shades from cream to orangey-brown. Mermaids are even rarer – if you’re really desperate to spot one you may need to head over to Mill Bay on the east of the island where they are said to have been seen reclining on the rocks in the middle of the bay. The Sands of Rothiesholm has its own semi-mythical beast – a seventeen-metre-long creature washed ashore in 1808 which was thought to be some kind of unknown sea serpent. Modern commentators suggest it may have been the bloated body of a long-dead basking shark.

Papa Stronsay

Lying just north-east of Stronsay, Papa Stronsay provides shelter for the ferry pier on its parent island. It has long been associated with those of a religious calling, being the site of a seventh- or eighth-century monastery. Today it is home to a congregation of traditional Catholic Redemptorist monks who run the Golgotha Monastery, farm the island and offer residential retreats. If rising for prayers at 5 a.m. isn’t your thing it may be possible to arrange a boat trip to the island with the monks.

Sanday

A quick look at an aerial photograph of Sanday reveals vast amounts of sandy beach giving rise to the island’s original Norse name of Sandey. The third largest of the Orkney islands, Sanday is divided into three peninsulas and is home to over 500 people. The island boasts a couple of shops (including the cavernous Sinclair General Stores where you can pretty much buy anything), a couple of hotels, a hostel, bed and breakfasts, self-catering cottages and even a community-run swimming pool.

Sanday is served by a roll-on roll-off ferry twice a day from Kirkwall on Mainland, often via Eday or Stronsay. There are also daily flights from Kirkwall. An on-demand bus operates on the island and should be booked in advance.

Dodge the tides to reach Start Point

Start Point lighthouse is built on a tidal islet sitting off the most easterly point of Sanday and can only be reached at low tide. Start from the road end beyond Thrave and head over the exposed pebbly causeway of Ayre Sound, aiming for the lighthouse. Vertical black and white stripes give this Stevenson lighthouse a unique appearance. The first Scottish lighthouse to have a revolving light, it replaced a more basic tower which proved inadequate at stopping ships getting wrecked just offshore. The massive stone ball from that tower now sits atop the old lighthouse on North Ronaldsay. Tours of the lighthouse can be arranged with the Sanday ranger. If visiting during the summer take care not to disturb the terns that nest off the foreshore – they will certainly let you know loud and clear if you get too close!

Stronsay, Sands of Rothiesholm

Sanday, The Croft

Sanday, Start Point lighthouse

Sanday, Whitemill Bay

Crawl into Quoyness cairn

A slightly less grand version of Maeshowe, this 5,000-year-old chambered burial chamber is one of the finest you’ll find anywhere, enhanced by a fantastic shoreside setting and lack of visitors. The cairn is made more atmospheric by the nine-metre crawl along the low entrance passage before you can stand up in the square central space. A torch is handy for exploring the side chambers. The best approach is to walk from Lady, crossing the narrow strip of Quoy Ayre with the sea either side before following the coast to the cairn.

Beachcomb at Whitemill Bay

The bleached sand of Whitemill Bay is the perfect backdrop for a spot of beachcombing. Starting from the parking area at the western end of the bay, this long arc of sand, backed by dunes, eventually leads to Whitemill Point where seals often haul out at low tide. Even if you have the sands to yourself, continue around the coast to the ruined farmstead at Helliehow and you may find yourself with a Hogboon for company. Rather like an imp, the Hogboon is a mythical figure said to have bullied the farm residents into moving only to hide himself amongst their belongings to continue his persecution of them – Helliehow remains deserted to this day.

Sample crofting life

Step through the low door of The Croft to see how life was lived in the early part of the twentieth century. Restored by locals, this typical two-roomed croft house sits alongside Sanday Heritage Centre on the outskirts of Lady village. Inside are box beds, a peat range complete with griddle for making oatcakes and bannocks, Orkney chairs made the traditional way from driftwood with woven backs, and plenty of genuine household items giving an authentic feel. Chat with the volunteers who helped restore the house; some of them remember growing up in properties just like this one.

North Ronaldsay

North Ronaldsay is an Orcadian anomaly: the most isolated inhabited island in the island group, it is served only twice a week by car ferry (weekly in the winter), though there are daily flights from Kirkwall. A visit here feels like a real step back in time from Orkney’s other islands. Although low-lying it is extremely rocky and exposed, and is best known for its seaweed-eating sheep and its two lighthouses. It’s home to fewer than seventy people, although there are moves to try and encourage more people to move here. The isolation means it’s a popular spot for migratory birds – there’s a bird observatory which also provides the main visitor accommodation, cafe and evening meals for guests. There’s also a cafe at the lighthouse. As with the other islands, the return flight is cheaper if you stay on the island overnight.

Walk the wall

A twenty-kilometre drystane dyke (wall) has been used since 1832 to keep North Ronaldsay’s sheep on the foreshore where they graze on the seaweed, freeing up the land inside for cultivation. The complete walk around the wall is an obscure Orkney classic, though it is rough-going in places and a tough undertaking to complete in one go. If you are fit and determined it can make a wonderful day, with plenty of opportunities for a bit of bird or seal watching. The very distinctive, shaggy brown to red Ronaldsay sheep will be your companions. They are smaller than more modern breeds and have adapted to life on the foreshore, grazing at low tide and ruminating at high tide. The gamey-tasting meat is particularly prized and served at a number of restaurants across Orkney. The island hosts an annual Sheep Festival where volunteers help repair the dyke as well as taking part in wool-related activities.

Visit the bird observatory

As Orkney’s most northerly island, North Ronaldsay is renowned by twitchers as the place to watch migratory birds in the spring and autumn and spot rare species that are unexpectedly blown in. The bird observatory is the place to hear about recent sightings and other bird-related news. It was founded in 1987 and has monitored the birds visiting the island ever since. Anyone can stay at the observatory which has bed and breakfast, hostel and camping accommodation, as well as a cafe; they often serve North Ronaldsay lamb. The observatory also has a number of opportunities for ornithological volunteers.

www.nrbo.org.uk

Left and Right: North Ronaldsay, the lighthouse

North Ronaldsay, the wall

Visit the light

Head to the north of the island to see the twin lighthouses that have served to protect seafarers from this stretch of coast which is notorious for shipwrecks. The Old Beacon is a twenty-one-metre-tall stone lighthouse built at Dennis Head in 1789 and lit with a series of oil burners and copper reflectors. The light was extinguished in 1809 when the Start Point lighthouse on Sanday came onstream, and the lantern here was replaced by the massive stone ball seen today. A number of wrecks proved the provision at Start Point was inadequate and the red-and-white-striped lighthouse was built just along the coast in 1852. At forty-three metres it is the tallest land-based lighthouse in the whole of the UK. A visitor centre, cafe and self-catering accommodation are housed in the lighthouse buildings.

Copinsay

Copinsay lies to the east of Mainland Orkney and is best seen from the Deerness peninsula. Now uninhabited, it is an RSPB bird reserve and its farmland is managed to foster wildlife including corncrakes. A huge number of seabirds including razorbills, guillemots, fulmars, puffins, black guillemots and shags nest on the high cliffs during the breeding season. The island is also home to a large colony of grey seals who pup here every November. Up until 1958 there was a resident farming population on the island as well as the lighthouse keepers and their families; the latter remained until 1991. Visiting the island relies on private boat charter or kayak but the tidal currents are particularly dangerous so local knowledge should be sought. Adjacent is the Horse of Copinsay, little more than a sea stack but with the attraction of Blaster Hole, a large blowhole, which can be viewed from a passing boat.

Stroma

Lying in the Pentland Firth between Orkney and the Scottish mainland, Stroma belongs to neither. It was home to over 300 people at the beginning of the twentieth century but is now abandoned. The population fell rapidly until the last permanent residents left in 1962, though lighthouse keepers continued to live here until 1997.

The houses in many of the two settlements are still standing – left to a slow decay, in many cases they still have all their furniture inside. The ferocious tides of the Firth that contributed to the decline of the community continue to make access difficult; it may be possible to arrange a charter boat from John o’Groats.

Swona

This smaller island to the north of Stroma suffered a similar fate, though it held on to its last inhabitants – a brother and sister – until 1974. While still in the ownership of two Orkney farms, the island is no longer farmed due to the difficulty of access. When the last people left – one was sick, and the other knew she might not be able to return – the sister released their beef cattle, eight cows and a bull, to roam free on the island. Several generations later the herd is still going strong and numbered seventeen at the last count. Living completely feral, the beasts have reverted to natural behaviour.

Landing on the island is difficult, and the good view of it from the Pentalina ferry from Gills Bay to Orkney is as close as most people will get.