FIGURES 13 to 16 Grandeur et décadence d’un petit commerce de cinéma (Jean-Luc Godard, 1986)

Land of the Pharaohs

In Jean-Luc Godard’s satirical Grandeur et décadence d’un petit commerce de cinéma (The Grandeur and Decadence of a Small-Time Filmmaker [1986]), two directors set about the task of producing a made-for-TV movie based on a pulp detective novel by James Hadley Chase. At one point in this mocking take on the commercial moviemaking process, a parade of somnambulant actors auditioning for the film file past a video camera for four minutes, mechanically voicing words that form a long sentence. The fragmentary lines are not drawn from Chase’s novel but instead from Faulkner’s short story “Sepulture South: Gaslight” (1954).1 Godard had already borrowed from Faulkner—quoting from If I Forget Thee, Jerusalem in both À bout de souffle (Breathless, 1960) and 2 ou 3 choses que je sais d’elle (Two or Three Things I Know about Her, 1966)—and would do so again, most notably alluding to Light in August and Absalom, Absalom! in his essayistic love letter to the filmic medium, Histoire(s) du Cinéma (1988–98).2

But here, Faulkner’s words—decontextualized and delivered in French in an expressionless way—hail from a minor, late story that was published in Harper’s Bazaar. “Sepulture South” is narrated by a young boy whose grandfather has recently died, a loss prompting the boy to “something like hysterics” and a fierce denial of his own mortality: “I won’t die! I won’t! Never” (US, 452). Later, however, his fear of death is reversed, the narrator realizing something different about the marble effigies in the cemetery representing his deceased relatives: “And three or four times a year I would come back, I would not know why, alone to look at them, not just at Grandfather and Grandmother but at all of them looming among the lush green of summer and the regal blaze of fall and the rain and ruin of winter before spring would bloom again, stained now, a little darkened by time and weather and endurance but still serene, impervious, remote, gazing at nothing, not like sentinels, not defending the living from the dead by means of their vast ton-measured weight and mass, but rather the dead from the living; shielding instead the vacant and dissolving bones, the harmless and defenseless dust, from the anguish and grief and inhumanity of mankind” (US, 455). And it is these final words of the story that would later hold unexpected appeal for Jean-Luc Godard.

Just as Godard’s movie drew inspiration from the story, so too Faulkner drew inspiration from a photographic image for his writing: “Sepulture South” was composed after he was shown a photograph by Walker Evans of the Wooldridge Family Monument in Kentucky, and the image appeared alongside his words when the piece was published.

The image and the words that accompany it also appear to closely correspond with the concerns of Faulkner’s writing more generally in the mid-1950s. In the same year that he published “Sepulture South,” Faulkner had worked on another story about immense tombs that divided the living from the dead: the screenplay for Howard Hawks’s Land of the Pharaohs (1955). Faulkner first worked on the script with Hawks and Harry Kurnitz, a young screenwriter, in December 1953, but the workplace was nothing like the studio backlot he was used to. At first, the team was located in a northern Italian villa for two weeks. From there they shifted to St. Moritz, Rome, and Cairo, for casting and location scouting, during which time Kurnitz apparently did most of the writing. A second draft screenplay was completed by February 17, 1954, and although the final script is dated October 2 of that year and bears only Faulkner’s name, it is unlikely that he had much to do with it, since he had left for Paris in late March. Indeed, a short note from Faulkner to Finlay McDermid, head of the story department at Warner Brothers, suggests his input was minimal: “In my opinion Kurnitz did most of job. Will support any credit suggestion he makes provided Hawks concurs. Faulkner.”3

FIGURE 17 Walker Evans, Wooldridge Family Monument, Maplewood Cemetery, Mayfield, Kentucky, 1945–47. Gelatin silver print, 19.9 × 19.2 cm (7⅜ × 7 $$$ in.). J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles © Walker Evans Archive, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

One other credited writer on the film, Harold Jack Bloom, would go further, suggesting that Hawks had employed Faulkner simply for the prestige of having his name on the screen: “as window dressing, so to speak.”4 Faulkner would later reluctantly use his newfound celebrity to help advertise the film, making a public appearance at a preview of the film in Memphis as a favor to Hawks.5 But in spite of the fact that Faulkner seems to have contributed very little to the screenplay, Hawks himself maintained that his writer of choice was instrumental in the project (in much the same way that Jean Renoir had emphasized Faulkner’s very small contributions to The Southerner in the previous decade). In an interview, Hawks confirmed that Faulkner “contributed enormously” to the project, and he was “the man for the assignment” for many reasons: “because his imagination was challenged by these men, their conversations, the reasons for their belief in a second life, how they happened to achieve these tasks for beliefs we would find it difficult to understand today, such as the slight importance attached to the present life in comparison with the future life, the rest that was to be assured to the Pharaoh in a place where his body would be secure.”6

On the face of it, Land of the Pharaohs is a simple story about the construction of the pyramids, and one that Faulkner knew all too well. “Land of the Pharaohs is nothing new,” he pointed out. “It’s the same movie Howard . . . has been making for 35 years. It’s Red River all over again. The Pharaoh is the cattle baron, his jewels are the cattle, and the Nile is the Red River. But the thing about Howard is, he knows it’s the same movie, and he knows how to make it.”7 An overstated comparison, perhaps, but one that at least draws attention to the fact that the film is less interested in local detail than it is in more transversal themes and character types. Perhaps owing to the property’s lack of attachment to the specificities of Egyptian history, Faulkner was able in one discarded scene to insinuate something of his own Mississippi. In this scene, which features the Egyptian ruler and his deputy Hamar, Faulkner reportedly wrote a physical conflict into the script, the pharaoh demanding that Hamar “leave go of my arm,” a throwback perhaps to a similar gesture in Absalom, Absalom!, in which Clytie twice grabs Rosa’s arm in an effort to prevent her from discovering some difficult family secrets. Harry Kurnitz noted that Faulkner was unsure of the likely speech patterns of a pharaoh, and understandably this southern scene in hiding did not survive the final cut.8

In the finished film, the pharaoh Khufu (Jack Hawkins) hires a foreign architect (James Robertson Justice) for the job of building a burial edifice that would be secure against grave robbers. All is going according to plan, until the pharaoh’s treacherous second wife, Nellifer (Joan Collins), who has designs on stealing his hoards of treasure and ultimately ruling Egypt, plots his murder. In the end, however, she is buried alive with her late husband, with traditional custom taking its revenge on the would-be usurper. Hamar delivers her chilling death sentence before shutting her inside:

HAMAR

Yes, the treasure is yours now. This is your kingdom—for the same twenty years it will take to tear it down stone by stone, that it took the husband you betrayed and murdered, to build it—It is yours now—all yours now—9

Although the story as a whole has its many points of interest, and this closing scene is certainly very effective, there is a real sense that the narrative was never of paramount importance in Land of the Pharaohs. More than words, here it is the images—shot on location and screened in beautiful WarnerColor—that are absolutely central to the film.

In the early 1950s, a new film format had emerged, dictating the importance not of complex dialogue and storylines but primarily of a monumental spectacle and the spectacle of monuments: CinemaScope. Indeed, in a later interview, Hawks confessed that he “made this film for one simple reason: Cinemascope,” a format that he had almost used for a similar story about the construction of an American Army airfield in China.10 The CinemaScope camera, which had been invented in 1953, was purpose-built to take in a more panoramic vision, its cylindrical lenses capable of an angle of view twice that of normal lenses.11 Effectively, the anamorphic images it created on screen, with an aspect ratio of up to 2.66:1, stretched each scene out horizontally, allowing more action to fit in each frame. With the potential to show multiple characters at the same time, the format promised longer takes and a shift away from the familiar shot/reverse-shot patterns that were ubiquitous in classical Hollywood cinema. And indeed, there are a few clear early examples of directors experimenting with the form: in The Robe (Henry Koster, 1953), a shot from a Roman archer at one extreme of the screen hits a Christian on the other, all without a cut.12 In general, CinemaScope films made between 1953 and 1955 suggest overall changes in editing patterns: in those years, as one study points out, “the typical range is between 180 and 350 shots per hour for ’Scope films, as opposed to 300–520 shots per hour for non-Scope ones.”13

FIGURE 18 Land of the Pharaohs (Howard Hawks, 1955)

Although he didn’t much appreciate the new format, Howard Hawks nevertheless grasped the value of CinemaScope for Land of the Pharaohs; “it can show things impossible otherwise,” he observed, because “you don’t have to bother about what you should show—everything’s on the screen.”14 And what better material for this more capacious aspect ratio than the construction of one of the seven wonders of the world? Not coincidentally, many films in widescreen formats (such as Paramount’s VistaVision and MGM’s Panavision) would be set in the ancient world, with swords and sandals stories such as Fox’s The Egyptian (Michael Curtiz, 1954), Paramount’s The Ten Commandments (Cecil B. DeMille, 1956), and MGM’s Ben Hur (William Wyler, 1959) all calling for ambitious, epic sequences shot in color. And Hawks had apparently planned two biblical epics to be made in Egypt—one about Solomon, the other about Ruth—both of which he wanted Faulkner to have a hand in: “It looks like I will be rich at last,” Faulkner wrote his wife about the anticipated contracts.15

Riches wouldn’t follow for Faulkner from these unrealized projects, but CinemaScope itself was associated with the prospect of great financial return in the face of the decline of the studio system. Its fondness for the exotic past was also soon cemented. In a scene from Godard’s Le mépris (Contempt, 1962)—itself shot in the wide-angle Franscope—the German director Fritz Lang (playing himself) expressed his understanding of the new format: “It wasn’t meant for human beings,” he makes clear at one point in the film. “It’s only good for filming snakes and funerals.”

Land of the Pharaohs, a film that shows more interest in picturesque landscapes than intricate storylines, contains both. Whether the new format would affect the craft of screenwriting or not, CinemaScope films would nevertheless still require writers. At Fox, Nunnally Johnson quipped that he would “have to put the paper in the typewriter sideways,” in order to accommodate the lengthened screen. Although “the emphasis at Fox under Zanuck has always been less on visual spectacle and more on story elements,” Johnson noted that the format “wouldn’t have altered anything in the writing.”16 Indeed, it is difficult to discern the influence of CinemaScope in Faulkner’s and Kurnitz’s scripts for Land of the Pharaohs: the heightened attention to the visual is certainly there, but there are no special directions indicated in either of the screenplays for longer takes or alterations to the shot/reverse-shot patterns of dialogue. The second draft screenplay for Land of the Pharaohs contains 225 scenes, while the final screenplay contains 249, suggesting more rather than fewer shots in the final production as it edged closer to the screen. The scripts do not exactly bear the hallmarks of CinemaScope, then. But in its content and its form, this film does forge a subtle allegorical connection between the future of cinema and the future of the human. For what Land of the Pharaohs demonstrates and what the format seemed to promise in general—the precarious survival of cinema amid the sudden rise of television, greater durability of film stock—went hand in hand with Faulkner’s work in the period more broadly, stressing as it did the indomitability of the human spirit in the face of atomic fallout and the difficulties of representing what Mark Greif points to in Faulkner’s writing as “a strictly abstract, universalized man.”17

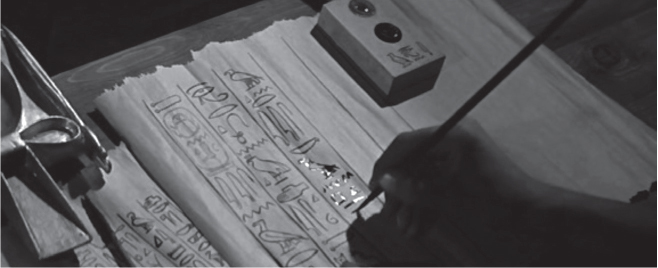

With his almost-completed novel, A Fable, Faulkner had moved further than ever from the South, seeking to make good on his declaration in his 1950 Nobel Prize speech: “I decline to accept the end of man” (ESPL, 120). But this is equally his aim in Land of the Pharaohs, which is to all intents and purposes an Egyptian story but at the same time signifies far beyond the nation. The written narrative is mostly buried within the exotic monuments on display, but in the tradition of the pharaohs, this grants it even greater power; although the words of the screenplay are seldom read, they live on in the images committed to celluloid in the film. While Nunnally Johnson would downplay the influence of the new film format on the screenwriter, the tension between words and images in Land of the Pharaohs as a CinemaScope film in the making is already presupposed in the very first scene of the screenplay. Continuing Hawks’s turn to the voice-over in his RKO films from earlier in the decade, at the start of the script Hamar begins to speak over a montage of images. And interestingly, this voice-over itself emerges from Hamar’s historical notations, as the high priest engages in a specifically pictorial mode of writing: hieroglyphics. The American poet Vachel Lindsay, in his Art of the Moving Picture (1915), had seen in the Egyptian hieroglyphs nothing less than a “moving-picture alphabet,” a universal language of pictures that could be read by anyone.18 And here, at the beginning of the film, Hamar’s written record of history promises to create a lasting document of Egyptian civilization:

FIGURE 19 Land of the Pharaohs (Howard Hawks, 1955)

15. CLOSE SHOT . . . PAST HAMAR.

The manuscript form of Egyptian writing.

HAMAR’S VOICE

(as he writes)

. . . this was the beginning . . . in the twelfth year of the reign of our Pharaoh, Cheops, the Second of that name, he returns in triumph to his palace in our great city of Luxor . . .19

In the film as produced, before anything else we see Hamar writing the chronicle of his pharaoh, speaking in voice-over at the same time as he inscribes hieroglyphs on the papyrus in front of him. The image suggests the enduring power of writing, especially picture writing, for posterity. But it also mimes the composition of the screenplay, in which Faulkner, Kurnitz, and Bloom, in consultation with Hawks, were crafting an original narrative, the words of which were always already subservient to the images they would create. Struggling over the appropriate language for the pharaoh to speak, the words that Faulkner would end up writing here were ultimately less memorable than the CinemaScope images Hawks created, building his shots—as Pedro Costa has written so poetically—“brick over brick like a mausoleum, like a huge graveyard.”20

Here a written narrative surrenders to the more powerful grammar of cinematic images. But like Hamar’s hieroglyphs, the words of the script did in fact manage to circulate beyond Hawks’s cinematic tomb, not only surviving in screenplay form in the Warner Brothers archive but also migrating into Faulkner’s prose after they had been written. As I have suggested, it is unlikely that Faulkner contributed much to the final screenplay. However, Nellifer’s last lines in that version of the script (as spoken by Joan Collins in the film) are suggestively Faulknerian in tone, especially when compared with two other bits of dialogue the author had written around the same time. As the queen’s fate is all but sealed, she pleads with Hamar to spare her:

242da (cont.)

INT. MAIN BURIAL CHAMBER:

Nellifer is now distraught and frantic, and terribly frightened. The noise is getting louder and louder as the stones fall—she clutches her head to try and shut out the noise.

NELLIFER

No . . . No . . . .

She throws herself on her knees, grasping Hamar’s arm—begging him, imploring him—but he is firm . . .

NELLIFER

I don’t want to die . . . please, don’t let me. please . . . I don’t want to die . . . .21

This last desperate appeal bears an uncanny resemblance to the hysterical words of the narrator of “Sepulture South” (“I won’t die! I won’t! Never”), but it also reminds us of the final lines of A Fable, which Faulkner completed just after he had worked on Land of the Pharaohs.22 These are uttered by the runner, a key character in the narrative who has ventured to the grave of the Unknown Soldier in Paris for the state funeral of the old general at the heart of the novel. The runner was horribly maimed by friendly fire during a mutiny that he instigated, which the military command averted by bombarding their own troops. In an effort to embarrass the criminally liable top brass, he throws his service medals on the general’s coffin and is promptly turned on and nearly beaten to death by the angered civilian crowd. Lying half conscious in the arms of an old veteran, he is last seen “laughing up at the ring of faces enclosing him,” and manages to speak his final lines through “blood and shattered teeth”: “That’s right,” he said: “Tremble. I’m not going to die. Never” (N, 4:1072). The runner, as Richard Godden points out, is the “everlasting deformity that cannot die,” produced by the brutality of war.23 And he is here counterposed against the other eternal product of the war, the tomb of the Unknown Soldier, who, as an abstraction, is likewise immortal.

Just as his final contributions as a screenwriter seemed thoroughly entombed in filmmaking history, William Faulkner’s words escaped once more: back to the South in a short story and to France in a novel, from screenwriting and into the fiction that has always seemed so far away from the studio back lot. Perhaps, with the narrator of “Sepulture South,” we as readers might now cease “defending the living” novels “from the dead” screenplays and instead understand that the two locked rooms of Hollywood and Mississippi were always more permeable than we thought.