Three

Liesel had never spent much time on the road. When she was younger, the children of Greymist Fair had dared one another to see how far they could go to the east or the west without turning back. Liesel had gone only once, and when she’d rounded the first bend and was out of sight of the village, the hairs on her neck prickled. When she turned back, the road was longer than it had been before, and she couldn’t see the village through the trees. Only when Tomas started calling to her did the trees part and the lanterns lead her home.

This time there was no one to call her home, so she imagined Tomas standing on the road at the edge of the woods, waiting for her.

The walk to the Idle River Bridge took hours. When she passed over the river and looked up, a heavy blanket of gray clouds covered the sky, but it was still bright enough for Liesel to know that it had to be nearing noon. The woods around her were still, the silence broken every now and then by distant calls of winter birds.

She stood in the center of the bridge and looked toward the other side, where Heike had found Tomas’s clothes. Liesel allowed herself a moment to imagine him there, to imagine him broken and bloody and splayed, and then she shut the image away and continued walking.

There were bloodstains on the stones. The lantern hanging there seemed like it should have been brighter or hotter than the others, but it wasn’t. She turned in a circle and peered into the gloom between the trees. Underbrush clustered around the roots and up against the side of the road near the lantern, so thick and wild it was a wonder it hadn’t yet grown over the stones.

She kneeled near the bloodstains. The children of Greymist Fair were not unaccustomed to blood or death, but it was not the same knowing this was Tomas’s blood. She took a few deep breaths. There—on one stone, so faint it might go unnoticed, were signs of smearing. The marks headed toward the right side of the road, where several branches had broken off a bush. Liesel got to her feet and went to investigate.

She didn’t want to find Tomas. She didn’t want to see what his body looked like now. But she also couldn’t leave him for the animals and the elements. He deserved to be buried beside their parents. She slipped between the trees, forgetting the forest, forgetting the wargs, forgetting herself. Far enough that no one would come looking.

She found the spot by smell. It was a shallow indent in the forest floor, crusted with congealed blood and surrounded by a strewn mess of branches and leaves. There was evidence of more dragging, but this was erratic with no attempt at camouflage. The animals had beaten her there. By now, there would not be enough of Tomas’s body left to recover.

Liesel raised a hand to wipe her eyes and found she wasn’t crying. Her emotions were still there inside her, but walled off. She was alone. What was she without her family? Even Hans didn’t care about her, if he ever had.

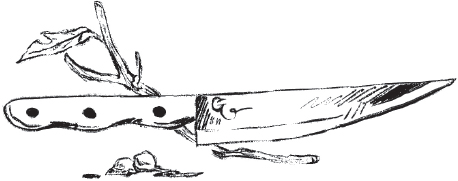

A wink of light in the brush caught Liesel’s eye. Half-hidden beneath the leaves and dirt was a small knife. The handle was made of oak, and the blade had been freshly sharpened. It appeared to have been hastily cleaned because blood still smeared it. In the metal, so small she almost didn’t see it, was a small flourish—the G that Godric etched in all his metalwork.

The wolf had dropped his claw.

Liesel turned the knife over in her hands, thinking of a wolf that walked on its hind legs with a belly like a pig, thinking of Hans rolling his eyes in front of the butcher shop, thinking of Jürgen helping her break the cold ground for Tomas’s grave.

Jürgen had lost a knife made by Godric.

Liesel sat by the well in the town square, watching the other villagers go about their business, Jürgen’s knife hidden in the folds of her skirts. Jürgen kept his knives in his shop; anyone could have stolen it.

A crowd was gathering outside the bakery. Ada Bosch was there, sobbing into her hands. Consoling her were other women, many of whom Ada did not normally speak to. It took Liesel a moment to see the connection; those other women had also lost children. Some very recently, others over the years.

Lost children were not uncommon in Greymist Fair. Even if they knew not to venture into the forest, they could not stop the forest from taking them. This was the way it had always been.

Liesel thought it was a little premature for Ada Bosch to believe her son had been taken, but maybe it was easier that way. The longer you held on to hope, the more painful it became.

The door to the butcher’s shop burst open, and Jürgen stomped out like a great fuming boar. When he saw Ada and the other women, he seemed to withdraw a bit in the face of their grief. Then he cast his gaze around, like he was checking to see if anyone had noticed his outburst, before he lumbered back inside his shop.

Liesel turned the knife in her hand. A great big belly like a pig. Jürgen had the biggest belly in town, and the comparison to a pig couldn’t be a coincidence—not because of his stomach, but because of his face. No one else in Greymist Fair fit that description. What if Jürgen had complained of his stolen knife to cover himself?

Why would Jürgen have been chasing her brother through the forest?