Four

Liesel did not wait for Tomas to appear in his shroud. When the moon was high, she tied her hair back, laced up her boots, and slipped out into the windy night.

The woods roared. Windows rattled in their frames, and the water bucket clattered and snapped against the well’s stone walls. Liesel worried fleetingly about the roof of her cottage, which had been leaking and would very likely tear off in a gale like this. But the worry fell away as quickly as it had come; she didn’t much care what became of her house.

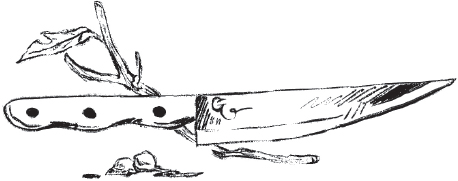

She kept the knife concealed in her skirts, even though there was no one to see her. Anyone who lived near the center of town had barricaded themselves in for the night, and most lights were out.

The butcher’s shop was dark, as was the attached residence. Hans slept like the dead, even during storms, but Liesel wasn’t as sure about Jürgen. She paused in the shadows, trying to decide how to get in. Finally, she settled on the shop. But when she crept around to the door, she found it locked. Jürgen’s knife was thin enough to slip between the door and its frame and lift the latch. The creak as the door opened was lost to the wind.

The shop was dark and reeked of salt and copper and sawdust. Jürgen’s business was one of opportunity: when hunters brave enough to venture into the woods came back with a kill, they gave it to Jürgen to butcher in exchange for the best cut of the meat. The remainder went to the first customers to arrive for it. Everyone traded and bartered in Greymist Fair. Everyone wanted meat, so Jürgen never lacked anything. Eggs, milk, wool, clothing, repairs to his shop and his house, new knives. Liesel had once heard Dagny joking that Jürgen must have gotten his wife in a trade, because there was no other way anyone would have married him.

Once upon a time, Liesel had thought this was unfair. Just because Jürgen was blustery and prone to anger didn’t mean he didn’t have something good inside him.

Now she thought she had been too charitable.

Behind the shop counter was a door. Next to the door, Jürgen kept several small candles. Liesel set the knife down and lit one, then realized with a breathy curse she was going to have to keep the knife in her pocket so she could cup her free hand around the flame and dim the light. She pocketed the knife, paused to listen for any noises in the house, then continued through the door behind the counter.

The reek intensified. The room was long and lined with butcher’s blocks stained nearly black, meat hooks hanging from the ceiling. The floor was dark. Jürgen’s many knives hung from the walls and seemed to grow out of wooden blocks; there were so many knives that Liesel wouldn’t have known one was missing if she didn’t have it in her pocket right at that moment. She crept into the room and jumped as the candlelight fell on a gaunt face on the floor.

She clapped her hand over her mouth to hold in her scream. Not a face. A skull. Maybe a deer. It was clean, stripped completely of flesh. On the long shelf above her, a row of similar clean skulls leered up at her with empty eye sockets. Perhaps the deer skull had fallen off. Liesel stepped gingerly around it.

There was a door to the left and another to her right. The one on the left led to the house. She’d seen it from the other side, knew where it would be in relation to everything else. The door on the right, though, she didn’t remember. She knew the first floor of the house ran right up against the back of the shop, but there was a jut of the wall where this door should be, pushing up against the fireplace. Like a cutout for a stairwell.

There was no handle on this door. Hanging from it was a jumble of hooks and rope, thick and heavy, as if the door wasn’t supposed to be a door at all but just part of the wall.

Then Liesel realized that it was supposed to look like the wall. The only reason she had recognized it as a door was because of the sharp shadows cast by the candlelight that showed her the door’s seam and the scuff on the stone floor beneath it that marked where it swung open.

Jürgen had a hidden door.

With the candle in one hand, she wedged the knife into the seam, levering the door open. It was heavy, and she had to move slowly to keep the hooks hanging on it from clattering together. When it finally opened, she was treated to a puff of the cold, musty air of deep earth. The wind howled outside. The bubble of light from her candle only extended down a few wooden steps. No sound came from the blackness below.

It couldn’t be a cellar. No one hid their cellar door, unless they were Gottfried and were paranoid someone was going to steal from them. It couldn’t hurt to check, though, just to see what was there. It was safer than going into the house, anyway, where Jürgen himself would be much more likely to appear.

Testing the steps to make sure they didn’t squeak—even with the wind outside, Liesel didn’t want to risk Jürgen catching the small sound of an intruder—she started down into the darkness, candle in front of her. Very quickly the wooden stairs and narrow walls gave way to dirt. The passage descended under the house, then began to turn, spiraling downward. She couldn’t fathom how long it had taken to dig it. And Jürgen must have dug it himself; anyone who had helped him would have long ago spread word to the town about tunnels under the butcher’s shop. Unless it was dug long ago. No longer hiding the light, Liesel held the knife in front of her, palm sweaty. The sound of the wind faded behind her.

The deep earth was quiet. She came to a gate made of heavy wooden beams, secured with a lock. The gate was roughly made, nothing like Ulrich’s work, but looked solid enough. Beyond the gate was darkness, but she could sense the nearness of walls, the lowness of the ceiling. There was a fetid stench, like unwashed bodies and human waste. Cold settled in Liesel’s bones. This was not a cellar, and the gate was not there to protect food stores.

Metal clinked. Liesel clamped her jaw shut. She became very aware of something watching her, something she couldn’t see. She froze.

She heard the breathing.