Five

Liesel backed away from the door, stumbling, gasping, the candle flame fluttering with the sudden movement. A small voice inside the room cried out, “No!”

The voice was young. A child. Metal clanked; chains shifting. Out of the darkness scrambled a thin, pale figure. It was a young boy, his hair freshly cut, his face smeared with dirt. More chains rattled. Small hands appeared from the darkness to grab at the boy’s arms and shirt, to try to drag him back. He fought with them, scratched them away.

“Oliver?” Liesel breathed.

Oliver, Ada Bosch’s youngest, turned back to her. He looked like death in the candlelight, his eyes black and deep. “Have you come to let us out?” he asked.

Liesel swallowed the bile that rose in her throat and took a step closer to the gate. “Us?”

Eyes appeared in the gloom, glinting in the light. Liesel counted three others, besides Oliver. She could not see their faces, but if they were other missing children, they had been here for quite some time.

“He keeps the keys on the wall there, behind you,” said Oliver, pointing.

Liesel found them. A keyring hung from a peg nailed high on the wall, a ways back from the door, much too far and high for any of the children to reach. The two keys were heavy, old; it would be hard for Jürgen to carry them around on his person without anyone getting curious.

“How did you get here?” Liesel asked as she grabbed the keys. “Jürgen did this?”

One of the other boys nodded. His name was Curt; he’d been missing for almost two months. “He doesn’t talk to us. But sometimes he comes down and takes us upstairs. The ones he takes—we don’t see them again.”

The larger key fitted into the gate lock and turned with a rusty squeal. Liesel froze and listened, but all was silent above her. She slipped into the room. The four children shrank away from her candle, hiding their eyes; there was no sign of candle or lamp or lantern down here, and no way at all for them to see sunlight. They probably didn’t even know what time of day it was, or that there was a storm raging outside.

The smaller key unlocked the collars. They were odd bits of iron crudely shaped. Like the door, the work of an amateur making do with what he had on hand and what he could craft himself. Liesel’s hair stuck to the back of her neck and her forehead as she pulled the chains free. The collars had apparently been pried open by brute force long enough to snap them around skinny necks, and she wasn’t strong enough to open them again. The children tolerated her, though Oliver was the only one who regarded her with any kind of trust. The other three, hair and clothes ragged, eyed her like wild animals, unsure if they were being led to another trap.

When their chains were off, Liesel held out her hand. “Come,” she said. “Hold hands. Stay together.”

Oliver grabbed her hand without hesitation. The sensation made her shiver; it could have been Tomas instead of Oliver. The others were more wary, but eventually followed.

She led them back up the winding tunnel. She lost track of how far they had gone and nearly crashed into the closed door at the top. She paused, confused. She was sure she had left the door open. She should have closed it, because anyone who came through the cutting room would see it open and know someone had gone inside.

Could have been the wind, she thought.

That door is too heavy and the wind isn’t getting into this room.

Carefully, she pressed her weight into the door and was relieved to find it opened. She peered through the crack and saw and heard nothing beyond.

Maybe the door is so heavy it swings back into place.

She pushed the door open far enough to slip through. The room was empty. She urged the children out of the tunnel. Their eyes were huge. The howl of the wind outside sounded like demons descending on the village. Liesel shepherded them to the butcher’s shop, glancing back at the house door as she did so. It was closed, too, as it had been.

The deer skull watched her from the shelf.

Screams erupted. She dashed after the children toward a hulking shadow holding Oliver aloft by the neck, little feet pounding against the shop counter. The others huddled behind the counter, screaming.

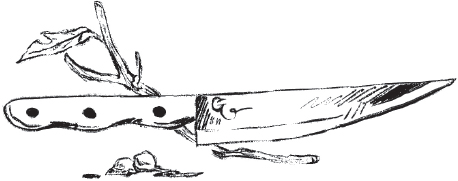

Liesel dropped her candle for her knife, threw herself at the round, heaving belly, and stabbed. The flesh parted easily. He dropped Oliver, bellowing in pain, and something heavy collided with Liesel’s head. She blinked—the room was spinning—she was on the floor, breathing sawdust. The shadow loomed over her, the knife protruding from its stomach. A dark hand reached for her.

Three children launched themselves over the counter and tore into the shadow, hair and clothing, skin and bone. Liesel lunged forward and grabbed the handle of the knife, tore it out. The shadow man roared.

“OUT!” Liesel yelled. “ALL OF YOU OUT NOW.”

The children slipped from the shadow man like snakes, disappearing through the shop door slamming in the wind. Oliver picked himself up, but he wouldn’t be fast enough to get out on his own.

The man charged. Liesel dove for the floor; the man crashed into the far wall. Liesel scrambled to Oliver, grabbed him, and hauled him outside.

He regained his feet quickly. Liesel shoved him away, hissing, “Run home!” He didn’t think twice. Not a moment after he’d disappeared in the night did the shop door snap open again.

She ran for the center of town. She didn’t know where else to go at this time of night, when everyone was asleep and the wind was so loud it could steal screams. Her head was still ringing. She stumbled every few steps, but she was faster than the gutted pig—for now.

The well appeared from nothing. Liesel hit it so hard her knees buckled. She caught herself from falling. She spun, dropped to the ground against its rough exterior, and held her arms braced, knife out.

She’d guessed right. He was behind her, and as she dropped, she ducked below his stomach. He speared himself on her knife right at the juncture of his legs. There was a gasp, a sudden impact of weight against the stone well, and a shift of momentum. The knife was ripped from Liesel’s hands. The shadow man tipped—shouted—disappeared.

There was scraping, several thuds, and finally a heavy splash. Then only the wailing of the wind.

Shaking, Liesel got to her feet. The well was deep enough that even the most fit among them would not have been able to climb out, not with the slick, cold stones that lined the inside. Her ears ached from the cold. She touched the side of her head and her fingers came away wet. She didn’t feel well. She needed to vomit, and then sleep for a very, very long time. She turned and looked down into the well. There was only darkness. The wooden bucket banged against its post.

She thought she heard quick footsteps nearby. She looked up. Her vision swam.

“Tomas?” she called out.

Two hands settled on her back, firm and bony, never warm. She knew those hands.

Liesel tipped like an empty bottle over the lip of the well, into darkness.