Chapter One

TRIP PLANNING AND PREPARATION

In everyday life, planning for survival isn’t an issue. Our societies have created extensive systems designed to bail us out in times of emergency. Should you be unfortunate enough to be involved in a car accident, chances are high that an ambulance will soon arrive and take you to an emergency room.

Well, there’s a big difference between waiting on the side of the highway for an ambulance and shivering on the side of a remote river in northern Canada with all your food and supplies washed downstream because you just wrecked your canoe running a Class IV rapid. Dialing 911 is not going to help you. The ambulance is not going to come. This is where trip planning and preparation come in.

I’m talking about more than just menu planning here. It’s great to know that you’re going to eat dehydrated chicken teriyaki with rice on the third day of your paddling trip, but what will you do if all your food is gone? That is a completely different situation, and one in which trip planning and preparation with an eye toward survival can make all the difference in the world. The most common cause of death in the wilderness is unpreparedness. Most people do some preparation before their adventures. Not to prepare would be the height of foolhardiness. But beyond arranging route, destination, camping spots, and meals, too few outdoor enthusiasts actually plan for the possibility of a survival situation.

Why? I suspect there are several reasons. Most people don’t consider the possibility of finding themselves in such a situation to start with, which can be a grave mistake. Others probably think they have enough survival skills, knowledge, and training, and therefore don’t need to contemplate the specifics of a particular trip. Some may feel that thinking of worst-case scenarios is pessimistic, and that it takes the fun out of anticipating a trip. But it’s not pessimistic to anticipate emergencies. It’s just good bush sense.

And the importance of planning and preparing for your particular trip can’t be overstated, because every region is different, sometimes in subtle ways. You could dramatically increase your chances of making it through a survival situation by getting just a few tips about the locale.

The more experienced you are in wilderness travel, the more likely you’ll have developed your own list of must-haves to bring on your adventures. Remember that each person is responsible for his or her own survival!

Do Your Research

PLANNING AND PREPARING FOR YOUR ADVENTURE BEGINS with research, a fairly easy undertaking in today’s information-rich digital age. Between the Internet and the countless books available in public libraries, the foundation is there for anyone to begin to build a location-specific store of knowledge for just about any region on earth.

Printed publications offer other benefits too, aside from the significant information they can yield. First, you can carry small guidebooks and pamphlets with you and—assuming they haven’t washed down the river with your canoe—refer to them along the way. Second, reading about your destination ahead of time gets you excited about the trip and empowers you with information that might save your life.

One thing to keep in mind when reading books or online materials, though, is that while they may describe, for example, the types of plants that can be sources of water in a specific area, you cannot be 100 percent sure that you’ll be able to identify a plant unless someone has personally taught you how. In this book, for instance, I note that you can find water in the chevron of the leaves of most banana trees. That’s all well and good, but you may need someone to show you a banana tree, and teach you how to distinguish it from similar-looking plants.

Ideally, anyone going on a backcountry wilderness trip should take the time to train in that region with a local expert, one who can offer such vital advice as which plants are edible and which ones will kill you. Take the time to find an expert, and try to dedicate at least one day with him or her on the land. The training and teaching may even be available in your own area. The first survival courses I ever took (to prepare me for northern Ontario) were offered in a city…Toronto.

Although local experts obviously know the best ways to build shelter, make fire, gather food, and locate water, I often find that it’s not the big lessons they teach that ultimately help me the most but the little nuggets of wisdom they throw out in passing. For example, when a native Costa Rican taught me how to eat mussels, he shared a tip with me: if the water that drips out of the mussel is green, it’s poisonous; if it’s clear, then it’s good to eat. That information was nowhere to be found in any of the books on the region, but it could have saved my life. On another occasion, a Kalahari Bushman taught me how to catch small weaver birds by hand by walking up to their nests at night and simply plucking them out of their holes. This is the kind of tip that you can’t find anywhere else, but that may prove invaluable if you’re stranded…and starving.

I realize that spending time with a local expert takes time and money. Most people have only one or two weeks off work and can’t dedicate time for training or education while on vacation. But if you can, it will make you more self-reliant, enhancing your trip in ways you never thought possible, even if you never get caught in a survival situation.

Ask the Right Questions

Now that you’ve committed yourself to learning about the area, your next question is this: What should I be looking for?

First, you should be intimate with your route and destination. Outdoor adventurers can spend hours looking at maps. It’s kind of like, well…map porn.

Carefully study your maps to get a feel for the land before you see it. As you come to understand an area’s features, you will begin to visualize the terrain in your head. Later, when you’re out there, nothing will surprise you. Beyond this, here are the vital things you should always know about any region you plan to visit:

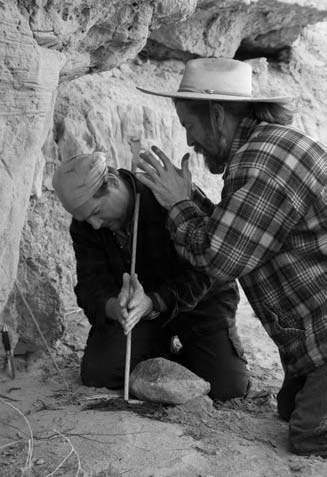

Had I not taken the time to learn from Kalahari Bushmen, I would have missed out on a plentiful—and easy-to-catch—source of food: the weaver bird (which, as shown here, I am attempting to pull out of a nest).

- What kind of vegetation, trees, or plants can you expect to find?

- Which, if any, of these are edible?

- Where are the water sources?

- What kinds of animals are there, and which are dangerous?

- What’s the worst possible weather for that area and season? (Checking the weather forecast is a must, as well: if conditions look bad, maybe you should postpone your trip for a while.)

- What will the day and night temperatures be?

- When do the high and low tides occur, and what are the levels?

- Who are the local people, what are their customs or taboos, and are they friendly?

People can play a bigger part in your wilderness adventure than you may think, and unfriendly people may prove a significant hurdle to overcome, even where I live in Canada. There is a river in northern Ontario that flows through a region that was once rife with controversy, part of the old “loggers versus tree-huggers” chestnut. At one point, the local logging community decided to take out their anger on anyone who traveled the river. More than once over a three-year period, groups of paddlers and anglers reached the parking lot at the end of their trips to find their tires slashed. Imagine if the campers had emerged with a time-sensitive casualty in tow!

There is no substitute for local knowledge. Here, I pick up the finer details of making fire with a hand drill from desert expert David Holladay in Nevada.

Learn to Use a Map and Compass

THIS BOOK OFFERS AN EXTENSIVE CHAPTER ON WILDERNESS NAVIGATION, but nobody should venture into the wild without at least the basic skills to interpret a topographical map and use a compass. You don’t play hockey without learning how to skate; you don’t go sailing without learning how to sail; and you don’t fire a rifle without learning how to shoot. So don’t venture into the wilderness without learning how to navigate. There are numerous local college courses available on the subject. Take one!

Always carry a map, whether you’re on your own or with a guide. If you’re with a guide but have neglected to bring a map, ask to see your guide’s as often as possible. Familiarize yourself with it, as well as with the route you are traveling. Your guide should not be annoyed by this, but rather pleasantly surprised that someone else on the trip is willing to become knowledgeable in case the worst should happen. After all, what would you do if your guide became incapacitated?

In preparing yourself by reviewing a route map, you may notice, for example, that a road runs parallel to the river or trail you’re traveling on. This is good to know should you run into trouble: A half day’s walk due east will put me onto a road and into the path of possible rescue. You may also see landmarks such as bridges, buildings, or even small towns. You would never have known that if you hadn’t looked at the map before it got lost or washed down the river.

Rely on Yourself, Not Your Guide

I’VE OFTEN FOUND THAT PEOPLE ARE FAIRLY GOOD about researching a trip if they’re going by themselves or in a small group. Where they get lazy is when they go with a guide. Assumptions are made that the guide a) knows what he or she is doing, b) knows the area really well, and c) has made all the necessary provisions in case of emergency.

Trust your guide, but don’t rely on him or her. In other words, you must be self-reliant. Remember that your guide, like you, is human. Guides have been known to make errors—whether out of lack of experience or bad judgment—that lead their parties into otherwise avoidable survival situations. And some of the grimmest survival stories ever told are borne of the fact that people blindly relied on their guides. Your guide will be grateful if you take responsibility for yourself, and you’ll feel empowered by doing so.

STROUD’S TIP

If you’re traveling in a group, share your survival knowledge and skills with your partners before disaster strikes. Make sure that everybody has a basic understanding of the steps they should take in an emergency. Remember, if you have an accident and are facing possible death, your travel companions are the ones you’ll have to trust to see you through to safety.

Get in Shape and Know Your Limits

AS WITH ANY PURSUIT THAT PLACES PHYSICAL DEMAND SUPON THE BODY, you’ll stand a better chance of making it through a survival ordeal if you already have a baseline level of physical fitness. How far you can trek in a day, how well you can build a shelter under extreme weather conditions, how effectively you can dig a hole for a solar still—all are directly related to your strength and conditioning. And with physical fitness comes greater self-confidence and self-esteem, both of which are critical to maintaining the will to live.

In general, the more we human beings focus on good nutrition and attain a high level of physical fitness, the more capable we are of accomplishing tasks, the more focused we are in our thoughts, and the more clear-headed we are. These are all attributes you’ll need if you find yourself struggling to survive.

For me, the importance of being physically fit is magnified when I venture into the wild. I am accepting the risk of undertaking these activities, and I have a responsibility to myself, my travel partners, and my family to be properly prepared. This isn’t to say you can’t trek into the wilderness if you’re not fit. But if you do, you’re putting yourself at a disadvantage from the start.

As part of physical preparation, consider seeing to any nagging or chronic health (including dental) conditions that may impede you. In the Hollywood movie Cast Away, Tom Hanks’s character, Chuck Noland, was marooned on an island with a painfully abscessed tooth. To me, that was one of the most realistic parts of the film, because these things can happen. If you are traveling in a group, it’s also a good idea to know what health issues your partners have, in case you need to look after them.

If you suffer from a chronic condition such as diabetes or high blood pressure, take this into account when planning your trip. And always carry enough medication to last you for longer than you expect.

Finally, if you’re planning to travel to an exotic or tropical location, make sure you receive any vaccinations you may need for diseases such as yellow fever, malaria, cholera, typhoid, hepatitis, smallpox, polio, diphtheria, and tuberculosis; an anti-tetanus injection is also a must. Failure to get the proper vaccines may leave you vulnerable to diseases prevalent in the area. Note that some vaccinations must be administered over the course of several months, so look into this well ahead of your departure.

Test Your Mental Fitness

THOUGH OFTEN OVERLOOKED, MENTAL PREPAREDNESS is an important part of the survival equation. And the best way to prepare yourself mentally for an outdoor adventure is to gain knowledge. Knowledge really is power, and it brings you the confidence you need to survive should disaster strike. Review the suggestions outlined in this chapter to help guide you through the research process. Before you leave, you should do the following:

- gather as much information as possible from printed sources

- contact a local expert who can inform you about the specifics of the destination: its flora and fauna, dangers, and any benefits or advantages (such as shelters, escape routes, or water sources) offered by the terrain

- receive at least basic training in wilderness survival and navigation skills

- gage your level of fitness and determine that you’re ready for your trip

- prepare a region-specific survival kit

If you’ve completed all the above tasks, you’ll know that if you find yourself in an emergency, you are as prepared as you can possibly be.

The other thing you can do to prepare mentally for a trip—and for any survival situation in which you may find yourself—is to accept that the worst can happen. If you head into any outdoor adventure with the notion that “It can’t happen to me,” you’re deluding yourself.

You should think exactly the opposite: “It can happen to me. I could end up in the middle of this wilderness alone, even though I’m rafting in a group of 12,” or “I could get turned around and lost, even though it’s just a Sunday hike and there are 75 other people out here today.” Once you accept the fact that an emergency could happen to you, the next logical step is to prepare so that it’s less likely to happen and so that you’re ready to handle it if it does.

Choose the Right Gear

IT IS IMPORTANT THAT ANY EQUIPMENT YOU BRING on an outdoor adventure is up to the task: strong and versatile. Don’t ask yourself if it will function under the best conditions, but rather, will it do so under the worst conditions? If not, do you want to stake your life on it?

Your equipment preparation is almost entirely dependent on your destination. Again, I recommend that you speak with someone local or, alternatively, talk to another traveler who has done the same sort of activity in the same place. They will help you to determine what equipment you need.

You can also learn about equipment by meandering around local outdoor stores that are tailored to the activity you’ll be doing. These are great places to meet people, especially other customers, who may have experience that could help you. Also consider posting a notice on a board in stores like these, to get in touch with other adventurers who may have knowledge to share.

STROUD’S TIP

Do not select your equipment based solely on what’s suggested in books and other print materials; these sources may contain too many errors and omissions, or may be out of date. It is important that you learn from other travelers’ personal experiences.

Assuming that you now have all the right equipment for your excursion, the next step is to make sure you know how to use it. Don’t make the mistake of thinking that you will have the chance to learn about your gear during your adventure. Your survival ordeal could take place within the first few hours of the trip, and you might panic because you don’t know, for example, how to set up your tent in a storm. So get yourself out in the backyard, on the deck, or even in the living room, and spend a few hours acquainting yourself with your gear. Practice setting it up and taking it down. Even more important, figure out how to fix it if it breaks; it may have to last you for a lot longer, or under more difficult circumstances, than you think!

Equipment planning and preparation pertains to clothing as well, yet another category in which a little local knowledge goes a long way. Don’t always trust the salespeople at your local outdoor store. I’ve seen many cases where a clerk has recommended the wrong item of clothing just because he’s been told to push a particular brand. Again, try to speak with other travelers who have been to where you’re going. Remember, poor clothing choices won’t make much of a difference if everything goes right, but they can sure go a long way toward making you miserable should things go wrong.

Wind, rain, cold, poisonous creepy crawlies, and extreme heat are some of the elements you may face. Your clothing should be able to withstand all of these. Make sure it fits well and is not too restrictive. You want clothes that will keep you dry and warm but that also offer enough ventilation to prevent overheating (see “Clothing,” Chapter 12).

STROUD’S TIP

Think of your clothing as your first shelter. Proper clothing should enable you to withstand extreme elements without building a shelter. So whether you’re surviving in the bitter cold of the Arctic or in a torrential downpour in the jungle, you should be able to stand still in only your clothing and survive.

While in the Canadian Arctic, I was outfitted with a caribou parka and pants, traditional Inuit gear. In temperatures as low as–58°F (–50°C), these enable the wearer to stand in a blizzard, impervious to the cold. Now that’s a great shelter!

Inform Others of Your Plans

TELLING PEOPLE WHEN AND WHERE YOU’RE GOING is a vital aspect of trip preparation. Unfortunately, people sometimes get lazy in this regard. Don’t. If you do, you may find yourself in the same situation as Jennifer and James Stolpa, a young couple who, along with their five-month-old son Clayton, got lost in a blizzard in northern Nevada in the early 1990s.

While driving to a family funeral in Idaho, they found their planned route closed by a snowstorm. They decided to take a detour but didn’t tell anybody about the change. Their truck later became stuck in the snow, and they found themselves stranded 40 miles (64 km) from civilization.

The Stolpas spent the first four days of their ordeal in their truck’s camper-shell. When nobody came along to rescue them (nobody knew where they were), they decided to attempt walking to safety, towing Clayton in a makeshift sled. When Jennifer could no longer walk, James found a cave for her and Clayton to stay in, while he continued on in search of help. Over the next 60 hours, James slogged almost 50 miles (80 km) in his sneakers before stumbling, incoherent, into the view of a passing motorist, who then helped rescue his wife and son.

Could this emergency situation have been avoided? I believe so. First of all, the Stolpas didn’t execute the best judgment in traveling against weather advisories and taking a back route to Idaho. But where they really went astray was in failing to inform anyone of their plan, a mistake that cost them their toes (lost to frostbite) and nearly their lives.

So anytime you’re undertaking a backcountry adventure—or any journey that takes you into remote areas—make sure that at least two different people (including local authorities) know, when appropriate:

- the nature of your activity

- when you’re starting out

- when you’re scheduled to finish

- your route

- how they can communicate with you

- how they can find you if there’s a problem

Fortunately, technology has come a long way in making wilderness travel safer. Websites such as SendAnSOS.com will allow you to enter your own personal travel plan. If you don’t sign in to the site after your return date, it will automatically send an SOS message to your contacts. Devices such as the SPOT satellite messenger not only allow others to keep track of your progress but also send an SOS message to your contacts when you push the Help button.

If you take advantage of all the planning resources and fail-safes available to today’s outdoor enthusiasts, you will radically increase your chances of making it through any survival situation.