How to be good at baking

General notes

I can’t understand people who say they are not good at baking, or that they are scared of it. In my experience it is simple: you find a good recipe, follow the method and get great results. But in order to be able to do that, you need to understand the instructions. The following guidelines should help, so if you feel you need some assistance, have a read through and get to grips with the basics (according to me).

The golden rule

I will repeat this again and again throughout the book: always read the entire recipe before you start and make sure you understand it. Whenever possible, I strongly advise setting out all your ingredients in advance too; that way, there is less chance of forgetting something. I tend to weigh all my ingredients, including the liquids, as I find it a more effective and precise method, so I have listed both gram and milliliter measurements for liquids throughout the book. You can find a conversion chart inside the back cover of the book.

Chocolate

The main types of chocolate I use in baking are:

• bitter dark chocolate with a cacao content of 62% and over

• dark chocolate with between 42% and 54%

• milk chocolate

• white chocolate

Use a brand you like (my rule is that if I don’t want to steal a piece, I shouldn’t be baking with it) and check the cacao mass. Be aware that you can’t substitute a bitter dark chocolate with one that contains a much lower percentage of cacao as it simply won’t perform in the same way. However, you can be more flexible with milk and white chocolate varieties.

How to melt chocolate

Make sure you are using dry utensils and bowls (even a little water can ruin an entire batch). Break or chop the chocolate into even-sized pieces before you start melting it. Then you can use one of two methods.

• Place the chocolate pieces in a dry microwave-safe bowl and set on high for a minute. Remove and stir. Return to the microwave for another 30 seconds, then remove and stir again. If it still isn’t fully melted, put it back in for additional bursts of 10 seconds, stirring in between each one, until it is completely liquid. Do note that microwaves vary in strength and chocolate is very easy to burn, so you will need to be cautious.

• The better method, I find, is to use a small pan and a bowl that fits snugly on top, so that there is no space up the sides for steam to escape. Pour some water into the pan. Place the bowl on top and check that it doesn’t touch the water (if it does, tip some out). Set on the heat, bring to the boil, then remove from the heat again. Put the chocolate into the bowl. Allow to melt for 2–3 minutes before stirring, then mix to a smooth paste. If this doesn’t prove sufficient to melt all the chocolate, you can return the pan and bowl to the stove on a very low heat for 2–3 minutes, but do watch it and take care not to overheat it or you will burn the chocolate.

When a recipe calls for melted butter and chocolate, I always start with the butter on its own. Use one of the methods above to melt it. Once the butter is warm and fully liquid, add the chocolate and stir until it dissolves.

When melting chocolate with a liquid, always bring the liquid to the boil first. Remove from the heat, pour over the chocolate pieces in a bowl and leave for 2–3 minutes. Place a whisk in the center of the bowl and whisk in small circular movements in the middle until you have created a shiny liquid core. Then whisk carefully until the chocolate and liquid are fully combined.

Chocolate sets and hardens as it cools, so if the recipe calls for melted chocolate, don’t melt it until you are ready to use it. Each recipe varies as to how and when to add the chocolate, so read the method carefully.

Sugars & caramels

The main types of sugar we use are:

• granulated sugar

• light brown sugar

• dark brown sugar

• confectioners’ sugar

• demerara sugar

• coarse sanding sugar (occasionally)

Each imparts a different texture and flavor and can affect the end result of your baking. You can swap them around a little, but you must make sure to dissolve the grainier sugars well if you want to achieve good results.

You can very easily turn granulated sugar into super-fine sugar (called caster sugar in the UK) by blitzing it in a blender for 15 seconds. You can even make it into confectioners’ sugar if you use a fine grinder, like a spice grinder. When I was growing up in Israel, grinding sugar ourselves was the only option, but luckily super-fine (caster) and confectioners’ sugar can be purchased easily these days, so I don’t usually have to bother.

How to make caramel

There are two main types of caramel.

• Wet caramel: This is used mostly for sauces and bases that require additional liquid. Place the sugar in a small, clean (ideally heavy-bottomed) pan. Turn on the cold water tap to a very light trickle. Hold the pan under the tap, moving it around so that water pours around the edges only, leaving the center of the sugar still dry. Remove from under the tap and use the tip of your finger or a spoon to stir very gently to moisten the sugar in the center, taking care not to get it up the sides of the pan. If you do, moisten your finger or a brush with some water and run it around the sides of the pan to clean away any sugar crystals. You should have a white paste in the base of the pan. Set it on the stove on the highest setting and bring to a rapid boil. Don’t stir it, but if you feel the urge, you can very gently swivel the pan in circular motions. Once the color deepens to a light golden caramel, remove from the heat and add your liquids or butter. Be careful as the caramel may spit and seize. If it does, return it to a low heat and continue cooking until it liquefies.

• Dry caramel: This is mostly used for decoration work or making brittles. Set a heavy-bottomed pan on a high heat. Once the pan is hot, sprinkle the sugar in a thin layer over the base; it should start to melt almost immediately. Stir with a wooden or heatproof spoon. Once the first layer of sugar has melted, add another layer and repeat the process. Continue until all the sugar has been dissolved and the color deepens to a lovely amber, then remove from the heat. At this stage you can:

• cool it (by dipping the bottom of the pan into cold water), if you are making decorations, or

• add butter and nuts, if you are making brittle, or

• simply pour it onto a sheet of baking parchment and allow to cool before breaking it up.

Flour

I am not wedded to specific brands but do like to make sure my flour is fresh. Check the “best before” / “use by” date and try to use it up before then, rather than letting it sit forgotten in your cupboard. If you have a large freezer, store it there for a longer shelf life.

I use a few different types of flour in my baking. Each recipe will state which one is needed.

• All-purpose: I use this for most of my cake baking and some of the cookies. It is the generic, standard flour sold everywhere.

• Bread flour: This is used in all my bread and yeast-based baking, and for cookies or biscuits that call for a very crisp end result.

• Self-rising: This is simply flour that has been activated with baking powder (very well mixed through). This gives a nice even rise to cakes. Sometimes I prefer the results you get using this flour to those you get by adding baking powder or baking soda by hand. If you don’t have any self-rising flour, you can substitute pre-mixed baking powder and all-purpose flour (use a teaspoon of baking powder for every 100g of flour).

Eggs

The freshness and flavor of eggs can greatly affect many desserts, especially ones that aren’t baked, like mousses and creams. I tend to use free-range medium eggs for baking, and the best eggs I can find for desserts that aren’t cooked through (and for eating generally). In the UK the tastiest eggs I have tried are from Cotswold Legbar and Burford Brown hens.

The best way to test if an egg is fresh (apart from the date stamped on it) is to dunk it in a bowl of cold water. If it sinks to the bottom, it is fresh; if it floats, it’s best not to use it.

I store eggs in the fridge to keep them fresher for longer but always let them come up to room temperature before using, as cold eggs can give very different results compared to warm ones, especially when whisking.

Sabayon is a general term used in many recipes containing eggs. It is created by whisking eggs, usually with sugar (which is sometimes heated to a syrup). You should ideally use an electric whisk to give you more power. There are a few stages to the process (the same stages apply whether whisking whole eggs or egg yolks) and I specify which one you need to reach in each recipe. The three stages that I refer to in this book are:

• foam: Whisking combines the eggs and dissolves the sugar, making the mixture foamy (like bubble bath), while remaining quite yellow. Reaching “foam” stage simply ensures that you have dissolved the sugar properly and added some volume to the eggs.

• ribbon: Whisked eggs at “ribbon” stage should look almost velvety, with a light yellow color. The larger bubbles present at “foam” stage condense as you continue to whisk, and after a while the ripples caused by the whisk start to hold their shape. Mixture trailed from the whisk onto the remainder will sit on the surface for a little while, resembling a ribbon (hence the name), before sinking back in.

• strong sabayon: This has a very pale color and more than three times the volume of the unbeaten eggs. A “strong” sabayon should have a nice firm texture, similar to whipped cream.

Meringue (as a term, rather than the crisp-baked sugar sweets) is reached by whisking egg whites (on their own or with sugar) and has its own stages. The main points to remember are:

• use eggs at room temperature or even warm, as cold eggs will take twice as long to whisk and will have a denser texture.

• always start whisking on a slow speed, then increase the speed slowly once the first bubbles appear. This will help you achieve a strong texture.

• add any sugar according to the recipe instructions.

• soft meringue stage is when the mixture coming off the whisk leaves a trace of “ribbon” on top of the rest of the egg whites; this will slowly sink back down (it is similar to “ribbon” stage when making a sabayon).

• strong or peaky meringue stage means that when you pull the whisk out, the egg whites hold their shape in a little peak that doesn’t sink back into the mixture.

Cream

I use heavy cream (42% fat) in the recipes in this book, unless something else is specified. Do remember that you can’t whip half-and-half, so it isn’t a suitable alternative in recipes that call for whipping.

When whipping cream, always use a whisk (it doesn’t matter if it’s manual or electric). There are four main stages to whipped cream:

• soft ribbon: The whisk just starts to create shapes that, if left alone, sink back into the cream.

• strong ribbon: If you lift the whisk slightly above the bowl, the trail of cream falling off it should leave a visible mark on the cream still in the bowl.

• soft whipped: The cream doubles in volume and starts to hold the shapes created by the whisk.

• fully whipped: The cream holds in little peaks when the whisk is pulled out. I would only whip cream to this stage when I intend serving it.

Butter & other fats

I tend to use unsalted butter in my recipes (I will always mention when there is an exception) and I use a good one. My rule for butter (which is similar to my rule for chocolate) is that if I wouldn’t spread it on my toast, then I shouldn’t use it in a cake.

Burnt butter, or beurre noisette as it is called in French, is made by heating butter in a saucepan until the water boils off and the milk particles turn a dark golden color and develop a lovely nutty flavor.

I occasionally use other types of fat, like margarine or shortening. This is usually in very traditional recipes where I have tried using butter instead, but have ended up deciding that the original was better.

Some recipes use oil as the fat. I sometimes specify a particular type of oil when I think that its richer flavor works well in that recipe, but the oils used are all interchangeable with a nice plain vegetable oil (e.g. sunflower).

Don’t use olive oil as a substitute as it has a very strong flavor and density. In fact, unless olive oil is specifically called for in a recipe, don’t bake with it.

Vanilla

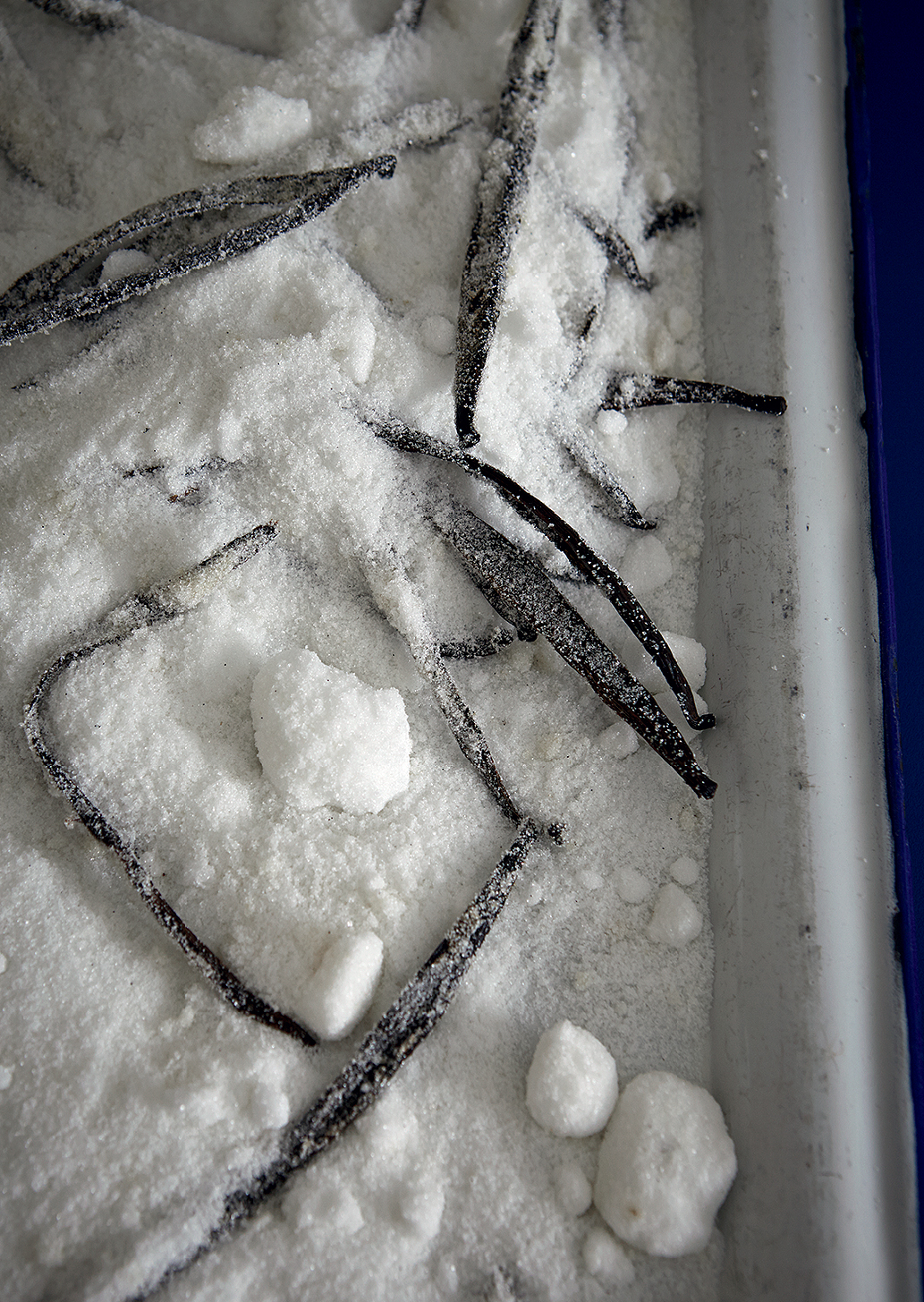

I generally only cook with the vanilla seeds and use the leftover pods to make my own vanilla sugar. Vanilla pods are pricey and you need to treat them with respect so that you don’t waste them. The best way to store them is in the fridge in an airtight jar or ziplock bag.

When you want to use a pod, run it between your thumb and index finger to flatten it, then lay it on a chopping board. Use the tip of a knife to slit it all the way along its length. If the recipe calls for only half a pod, put the other half back in the container in the fridge. Hold the curly tip of the pod with one hand and use the blunt side of the knife to scrape along the inside of the pod so the little black seeds accumulate on the back of the knife. Use the seeds in your recipe, then place the empty pod in a jar of granulated sugar and shake about to infuse (see the vanilla sugar recipe here).

Gelatin

Gelatin is a tricky one as there are so many forms. The pig stuff (God help us) comes in several different grades of thickness, so it is best to check the instructions on the packet for the recommended leaf to liquid ratio. The guidelines on the gelatins that I use advise one leaf for every 100g/ml of liquid. You can also use a vegetarian gelatin substitute, but you will have to figure out the appropriate amount yourself.

Whatever type of gelatin you use, I think it is best to have a soft-ish jelly. Definitely don’t add too much, as a hard or rubbery full-set jelly is horrible to eat.

Do note that you need to adjust the amount of gelatin depending on whether you are making individual jellies or one large bowlful. As a general guideline, when using a recipe for a large jelly, I deduct one leaf of gelatin for every 500g/ml of liquid if I decide to make it in a number of small molds instead. Similarly, if you take a recipe that makes individual portions but decide to set it all in one large bowl, add a leaf for every 500g/ml of liquid.

Nuts, seeds & roasting

I buy most of our nuts and seeds fresh, whole and already shelled, and roast them when I need them. Only almonds are bought in other forms—ground, flaked, blanched and slivered—to use in specific recipes, as commercial machinery can achieve a better texture than I can by chopping or grinding.

I use the following table as a guideline for roasting times. Always lay the nuts or seeds in a single layer on a flat tray for best results.

Nuts / seeds: Whole almonds, skin on

Temperature: 350°F/325°F convection (nice and low to roast through without burning)

Roasting time: 15–18 minutes

Nuts / seeds: Flaked, blanched or slivered almonds

Temperature: 375°F/350°F convection

Roasting time: 10–12 minutes

Nuts / seeds: Pine nuts, sunflower seeds, pumpkin seeds or sesame seeds

Temperature: 400°F/375°F convection

Roasting time: 5 minutes, shake the tray, then a further 5–8 minutes till golden

Nuts / seeds: Pistachios, walnuts and pecans

Temperature: 400°F/375°F convection

Roasting time: 10–12 minutes

Nuts / seeds: Hazelnuts

Temperature: 350°F/325°F convection (nice and low to roast through without burning)

Roasting time: 14–16 minutes

General baking terms

Creaming: This term is used to describe combining fat with sugar in vigorous circular motions to dissolve the sugar. Usually done with a paddle attachment (if using a mixer) or a firm spatula or wooden spoon (if working by hand). There are a couple of levels to creaming:

• light creaming dissolves the sugar without adding too much air and so keeps the fat quite dense. The fat will have lightened in color and doubled in volume.

• strong creaming adds much more air while dissolving the sugar. The fat will be very fluffy and tripled in volume.

Folding: This generally involves gently working two mixtures together, usually one lighter and one heavier. The aim is to retain as much air in the mixture as you can. This is done with a spatula and a very light hand, scooping carefully and repeatedly up from the bottom of the bowl in the same direction each time (using either a circular or a figure-eight motion) until the mixtures combine.

Piping: I almost always use a disposable piping bag cut to the required size to fill tins with cake batter, as I find it cleaner and more controlled than using spoons. However, if you are a little clumsy with a piping bag, or think piping is more work than it is worth, then use two spoons, one to scoop and the other to push the batter off and into the tin. You will see that I also like to weigh the amount going into each tin when baking individual portions so that they will all be the same size and take the same amount of time to bake, but you don’t have to do this if you think it is a step too far.