11

BUT THEY DID PASS—WORLD WAR II

Taking part in the Spanish Civil War changed Hemingway, and his writing, forever. His involvement on the side of the Spanish left was no temporary spasm. After all, his first vote in a U.S. election had been for the imprisoned socialist candidate Gene Debs. His passion for the Loyalists was the logical outcome of where he’d been heading since that mortar fragment shattered his leg and his psyche. In Spain he became a committed “fellow traveler,” an adherent supporter of, but not a slave to, the Communist line of the fight against fascism wherever it reared its ugly head. With great discomfort and awkwardness, he spoke from public platforms to beg money, and he financed and narrated a propaganda film, Spanish Earth, by the Communist filmmaker Joris Ivens. Hemingway’s second wife Pauline, who was Catholic and thus pro-Franco, would never have tolerated his “communism,” but after their divorce she was largely off stage.

Something happens to Hemingway after the defeat of democracy in Spain. His heart cracks a little. He becomes a stranger to himself. A balance shifts from the private writer to the public celebrity. More than ever he becomes the world-famous HEMINGWAY in capital letters. His split from Pauline to marry Martha meant leaving Key West for a new place, one chosen for him by Gellhorn: the 15-acre Finca Vigia (“Lookout Farm”) outside of Havana, Cuba, where he wrote For Whom the Bell Tolls. He would live and write in Cuba until Fidel Castro took power.

Martha Gellhorn fell in love with the writer but then found herself in bed with a needy, angry, me-first-and-always Famous Man whose preferred pleasures were heavy drinking with disreputable pals in Havana bars and testing himself against the god of the waters by marlin fishing on his beloved boat, the Pilar. Martha was as brave as any of his bullfighters and was eager to keep reporting the blood-and-guts of conflict in China, Finland, or wherever, but after fighting in two wars and reporting on several more, Hemingway, with his shattered body, was dog-tired of combat. Also, he may have been demoralized by the inaction of the Western democracies to help Spain in its agony. Hemingway needed a rest.

Gellhorn wasn’t having it. She had found a lovely home for him in Cuba overlooking an expanse of lush green land. Hemingway wanted to relax and enjoy it. For him Finca Vigia was another link to his boyhood idol, Teddy Roosevelt, who with sabre and pistol had liberated Cuba from its Spanish overlords. Now his idea of recuperation was to keep writing steadily and to forget about war; but it wouldn’t forget about him.

After the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, and after the United States declared war on the Axis powers, Ernest’s hanging around the Floridita bar in Havana instead of doing something was not Martha’s idea of patriotism. Like a young Hemingway, she itched for action, and with Ernest’s help she became a war correspondent for magazines. To his growing displeasure she took the job seriously. “ARE YOU A WAR CORRESPONDENT, OR MY WIFE IN BED?” he telegraphed her as she was covering the Allied invasion of Italy.

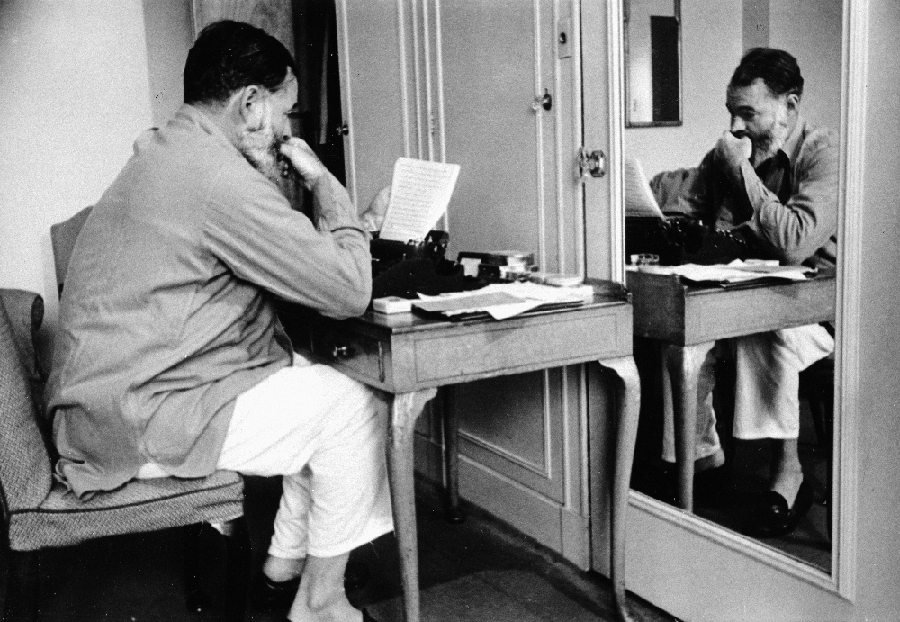

While Martha was off interviewing GIs in foxholes, her husband was back at Finca Vigia, where he spent the mornings happily at his old typewriter pounding out stories, fragments and parts of what later became The Old Man and the Sea, and some of his later, very best work not published until after his death, and spent the afternoons drinking up a storm. But Martha kept after Ernest to get “more involved” in the war effort and, again, to lay his bruised body on the line, at age forty-three. So that’s what he did, by becoming a spy for the U.S. government in Cuba.

Hemingway called his spy ring of happy-go-lucky Nazi hunters his “Crook Factory” because that’s what some of them were: drinking buddies and shady characters. Their self-assigned task was to track some of the many pro-Hitler Spanish fascist Falangists who had taken refuge in Cuba during the recent civil war. The U.S. ambassador in Havana liked Hemingway and backed his skullduggery, but J. Edgar Hoover was furious that such a “well known Communist or sympathizer” was doing work the FBI should have been doing itself. Worse, Ernest poked his nose into corrupt links between Cuba’s dictator Batista and American corporations. Hoover reopened Hemingway’s FBI file, by now a hundred pages thick, probably begun when the author went on fund-raising tours to buy ambulances for Loyalist Spain. In Havana, it didn’t help Hemingway’s relations with “the Feds” that he went around sneering at Hoover’s FBI agents as an “American Gestapo.”

The FBI director had a delicate problem because Martha was friends with the president’s wife, Eleanor Roosevelt, and sometimes stayed in the White House. Eleanor was too powerful and media-wise to be messed with. So Hoover had to move cautiously against Hemingway (although, with a classic bureaucrat’s long memory, he would take full revenge twenty years later).

Martha jeered at the “juvenile antics” and was insensitive to Hemingway taking his counterintelligence work so seriously, especially because he wanted to have fun with it, too. How to merge pleasure fishing with spying? Easy. He outfitted his beloved boat Pilar with machine guns, hand grenades, and plenty of rum, and, with the carousing Crook Factory gang aboard, patrolled the waters off southeastern Cuba to hunt for prowling Nazi subs. (The subs really were out there sinking Allied ships.) The plan was to locate a sub, board her pirate-fashion and toss a grenade down the hatch. The Crook Factory never did find their Nazi submarine. Martha, with her usual lack of tact, laughed at him in front of his pals. He nursed a grudge.

Hemingway got his revenge by wangling an assignment as a war correspondent in the impending Allied D-Day invasion of Hitler’s Fortress Europe. He did it very nastily by bumping Martha off her own Collier’s war assignment to take it for himself. She was terribly hurt, and very angry. Undaunted, Martha smuggled herself on a D-Day-bound hospital ship and got to France even before Ernest because the military held him back as “precious cargo.” The last thing the brass bureaucracy wanted was to have America’s most famous writer killed on their watch. But once he landed on the beach he was back in his element, men at war. He kept telling people how scared he was amidst whizzing bullets and exploding shells, but in fact he loved the risk. Military bureaucrats frantically tried to keep him away from the action. “HEMINGWAY KILLED AT THE FRONT” was not their idea of good p.r., but suddenly he felt nineteen again and combat-ready.

He was not in good physical shape. Among his many illnesses and injuries was a concussion he suffered in a London blackout car crash just before he landed in France. The gash to his head required over fifty stitches. If he expected maternal sympathy from Martha he was disappointed. Visiting him in the hospital she made fun of his injuries and told him he was a fool for being involved in a drunken auto wreck. It was the beginning of the end of their marriage. Because, in London, he’d already met the female antidote to Gellhorn. Mary Welsh, another journalist, was caring and worshipfully blind to his faults. Sensing a possible vacancy in his bed, in the same hospital she made a play for the emotionally and physically vulnerable Hemingway to which he eagerly responded.

Hemingway in London

Unlike Hemingway, with his vengeful heart, Gellhorn was reticent about their sex lives—except just once, in a late-in-life interview in which she lightly spoke of not having enjoyed making love with him. The engine of their romance had always been professional rivalry. The story I like best happened in France when Hemingway and Gellhorn were covering the war at the same time. As they were riding in a Jeep near the Allied front lines after D-Day, a Nazi V-2 rocket sped overhead. In the presence of Allied officers, and to Hemingway’s shame, she sharply reminded him, “Remember Ernest. That V-2 story is mine.”

In the Allied drive to Germany he had other Jeep accidents and a narrow escape from a Stuka dive-bomber, whose screaming whine was all too familiar from Spain. Plagued by headaches and double vision, he was still able to put together another Crook Factory made up of francs-tireurs, French partisans, to shoot Germans and—in his version—personally liberate Paris. Hemingway and his merry pranksters fought their way past Germans to get to the city where he’d first felt truly alive. Arriving in Paris the first thing he did was joyfully reunite with Sylvia Beach at the Shakespeare and Company bookstore on Rue de L’Odeon—his second home in the 1920s. Sylvia asked Ernest to clear some Nazi snipers from nearby roofs, which, armed with a submachine gun, he and his partisans promptly did. Under the Geneva Convention a civilian journalist like Hemingway must not carry a weapon, and Ernest’s caper forced an embarrassed U.S. military to put him on “trial” where he was “sentenced” to a Bronze star for bravery.

Although he cut a ridiculous figure swaggering about Paris with a bottle of champagne in his hand and boasting of his exploits in the bars of the George V and Ritz hotels, in fact he could easily have been killed fighting his way from the D-Day beaches to Paris. In physical terms he was now practically an old man, half blind, and in poor health with splitting headaches from a damaged brain.

All this time, consciously or not, Hemingway was gathering material for what he hoped would be a great World War II novel. He almost got killed doing it.

(In the same European war theater, Ernest’s first son “Bumby” was captured fighting with the French resistance and taken to a German prisoner of war camp till war’s end. Leicester, Ernest’s younger brother, also fought in France and Germany.)

The remarkable short story “Black Ass at the Crossroads” was never published in Hemingway’s lifetime. The original manuscript was kept in the Hemingway Collection at the John F. Kennedy Library as part of his papers. According to Paul Fussell, a scholar-soldier wounded in the same European campaign, the story, about an ambush of German soldiers by an American infantryman, who suffers great remorse for what he has done, and “is so realistic and so inexplicable in any other way than to believe that Hemingway was there and that perhaps it was never published because it was too incriminating.”

After resting up from “liberating” Paris in August ’44, Hemingway went forward to the most hellish fighting. The Battle of the Hürtgen Forest, on the German border, was an American calamity. It was fought—endured is a better word—in a mixture of rain, snow, sleet, fog, and knee-deep mud, in one of the worst winters on record, against a dug-in German army. The GIs in the Hürtgen, exposed, under-armed, summer-uniformed U.S. infantry, were sacrificed by their comfortably rear-echelon generals—Omar Bradley and Courtney Hodges and their boss the Supreme Allied Commander Ike Eisenhower—who kept throwing them in needless assaults under murderous shellfire tree-bursts. A tree burst occurred when a German shell explodes at the top of the thick forest, sending deadly wood splinters vertically down on soldiers who had not been trained against this type of warfare. Any idiot private could have told the top brass that flanking the thickly wooded hills—going around it—would have been more productive tactically and helped saved the 24,000 Americans who died in this useless assault.

Over three cold, wet, miserable months, the Hürtgen became the U.S. army’s longest-ever battle. I know about this disaster because I joined one of its lead elements, the Fourth Infantry Division, after they returned from Europe, decimated and shell-shocked, and I had a chance to talk to its survivors. At one point the Fourth’s 22nd Regiment suffered eighty percent casualties; some battle companies took nearly two hundred percent casualties—that is, every soldier had to be replaced twice over (see Paul Fussell’s The Boys’ Crusade).

Hemingway took one look at this Hürtgen killing field, mud up to the axles and foxholes useless under shell blasts, entrenched Germans zeroing in with mortars and Maschinengewehr, and saw instantly the American troops were sitting ducks. He joined up with the 22d Regiment led by the sonnet-writing Colonel “Buck” Lanham, who became the model for Col. Richard Cantwell, the heartsick and war-bruised hero of his next novel, Across the River and Into the Trees. After the war the poet John Ciardi, himself a veteran, saluted: “What counts, as I see it, is the way in which the GIs of World War II lived and died with Hemingway dialogue in their mouths … Their language was not out of Hemingway but out of themselves.”

In freezing sleet, under fire, an American officer peeked out of his foxhole in the Hürtgen and saw on the front line a “… tall man in olive drab trousers, combat boots, a knitted helmet liner, and a steel helmet … By contrast, the spectacles astride his nose seemed pitifully small and inadequate.” Hemingway was carrying a Thompson sub-machine gun. Contrary to his promise at his military tribunal back in Paris, he mixed shoulder-to-shoulder with the scared half-frozen soldiers. At one point Hemingway substituted for the famous war correspondent Ernie Pyle for the army newspaper Stars and Stripes. To GI’s waiting in their foxholes for a visit from their beloved reporter, Hemingway would show up instead and sliding in beside them would thrust out his hand and say, “Hi, I’m Ernie Hemorrhoid—the poor man’s Pyle.” No wonder soldiers loved this sick, brave old guy. Desertions were rampant. Pvt. Eddie Slovik, terrified of the Hürtgen bloodbath, ran away and was executed by firing squad, the only U.S. soldier in World War II to be shot for desertion. His execution order was confirmed by Eisenhower, one of the very generals responsible for the Hürtgen fiasco.

With Colonel Charles “Buck” Lanham

Hemingway survived Hürtgen although many of Buck Lanham’s men and officers did not. Before the war in Europe ended the author-journalist-soldier was back at Cuba’s Finca Vigia with his new, fourth wife, Mary Welsh. (For perspective, Saul Bellow had five wives, Norman Mailer six, and J. D. Salinger three.)

Mary Hemingway

Ernest and Mary, who like Martha soon came to resent his bullheadedness, quarreled even on their wedding day and kept it up for the next sixteen years of their marriage. Beware a woman who gives up her career for a man. (Remember Grace!) Perhaps Mary’s ultimate revenge took the form of tinkering with his posthumously-published work, such as Islands in the Stream and most intrusively one of Hemingway’s most popular books, A Moveable Feast (later re-edited by Sean Hemingway, his grandson by Pauline’s son Gregory).

By the end of World War II, there hadn’t been a published work of Hemingway fiction in six years. Critics, those “lice who crawl on literature,” muttered that he was finished. Hold on, not yet. All the time that he himself complained of being “out of business” as a writer, or that critics were destroying him, he was working fiendishly hard, first at Finca Vigia in Cuba and then out west in Sun Valley, Idaho. Ever since he’d been invited by Averell Harriman, chairman of the Union Pacific Railroad, to help publicize the Sun Valley Lodge as a way to increase train ridership west of the Rockies, Hemingway had been a part-time Idaho resident. He liked the landscape and the people. “I think he was in search of the vanishing frontier,” speculates one Hemingway scholar. “I think he was in search of a place where he could have some anonymity, where the hunting and fishing was still good. And he found that in Central Idaho.” Out west, Hemingway put his energy into what he hoped would be his truly major work and thus reinstate him in his own eyes as a functioning Great Author.

Let’s look at what he was trying to do when he came back from the European war. Nothing less than a trilogy of three big novels he called “Land,” “Sea,” and “Air” that became The Old Man and the Sea, Islands In The Stream, and A Moveable Feast. Multi-tasking, he was also strenuously pushing the envelope—and his sanity—with the strange, androgynous, and fascinating gender-reversal novel The Garden of Eden. Hemingway was finished, was he?

Hemingway kept writing under the gun of terrible depressions, headaches, amoebic dysentery, insomnia, a subdural hematoma (blood on the brain), dizziness, deafness, amnesia, and dyslexia—as well as the trauma of serial deaths of friends starting with his valued editor at Scribner, Max Perkins, followed by Scott Fitzgerald, James Joyce, Sherwood Anderson, and Gertrude Stein. Losing people who are your living memory can inflict a deep psychic wound.

How did he manage? He may have been sick as hell but he was a great guy to have around in an emergency. At Finca Vigia in Cuba, before the Idaho move, Mary had a life-threatening ectopic pregnancy, which is when the fetus is stuck in the Fallopian tube, and the doctor refused to give her a blood transfusion because he felt her veins couldn’t take a needle. Without a transfusion she would have died. Ernest, who had witnessed many battlefield plasma transfusions, stepped in and brusquely showed the hesitant doctor exactly how and where to do it, thus saving her life. Around the same time, his secretary Nita fell off the Pilar into shark-infested waters and screamed for help. Without hesitating, knife between his teeth, he dove in to get his body between Nita and a circling shark. Then he climbed back aboard the boat so that he and Mary could continue to fight and hurl dishes at each other.

In this same period of furious writing, his middle son Patrick had a bad car wreck that required round-the-clock care as well as electroshock treatments. Papa Hemingway stayed with his boy for over a month, taking the long night shift. Hemingway the bully, braggart, dirty fighter, philanderer, and chest-thumper was also a nurturing, caring, generous, self-sacrificing, and loving dad.