13

ACROSS THE RIVER INTO A STORM OF FLAK AND THE OLD MAN AND THE SEA

While working on his Land-Sea-Air trilogy, caring for a sick son, fighting with Mary, and restlessly shifting homes from Havana to Idaho, Hemingway suddenly hit an extraordinary writing streak. He had to be in love to write at his most virile and energetic. And now, age fifty-one, he was crazy over the lovely nineteen-year-old Adriana Ivancich, and her city of Venice, Italy.

“Then she came into the room, shining in her youth and tall striding beauty,” Hemingway wrote of Adriana re-named as “Renata,” the heroine of his 1950 novel Across the River and Into the Trees. “She had pale, almost olive-colored skin, a profile that could break your, or anyone else’s heart, and her dark hair, of an alive texture, hung down over her shoulders.”

Adriana Ivancich, self-portrait

Adriana was the beautiful daughter of a Venetian aristocrat. They met while he was on a hunting trip in Italy. For seven years, whenever they were separated, he sent her long, effusive letters. From Nairobi in 1954, after two plane crashes in two days left him with severe internal injuries, he wrote, “I love you more than the moon and the sky and for as long as I shall live. Daughter, how complicated can life become? The two times I died I had only one thought: ‘I don’t want to die, because I don’t want Adriana to be sad.’ I have never loved you as much as in the hour of my death.”

In The White Tower (1980), her own book about their relationship, written thirty years later, Adriana says, “What happened when we met is a little more than a romance. I broke down his defenses; he even stopped drinking when I asked him to. I’m proud to remember I led him to write The Old Man and the Sea.” She denies she is the model for Renata in Across the River—on publication, it caused a local scandal in Venice, and she was ostracized for a while. But she does take credit as his muse. “Yes, naturally he wrote [Across the River] for me, thinking of me, but I didn’t like the book and I told him so.” In the semi-autobiographical story, a middle-aged colonel and young Renata make furtive love in a gondola. In her own book, Adriana insists that they never indulged in anything more than occasional kisses. (There is speculation that Hemingway may have been impotent at that point.) “He said words flowed out from him easily thanks to me. I simply uncorked the bottle,” she wrote.

Across the River and Into the Trees, which takes place in post-WWII Italy, was almost unanimously put down by critics. (The title comes from the alleged dying words of the Confederate general Stonewall Jackson.) Wincing as I turned each page when the book came out, I told myself, the Old Man has lost it.

Colonel Richard Cantwell (alias, Buck Lanham plus Hemingway himself) returns to Venice, the city he fought for in World War I. (“Christ, I love it,” he said, “and I’m so happy I helped defend it when I was a punk kid.”) Cantwell, facing imminent death from heart disease, is a “beat up old bastard” proud of his disfiguring wounds. “He only loved people, he thought, who had fought or been mutilated. Other people were fine and you liked them and were good friends; but you only felt true tenderness and love for those who had been there … So I’m a sucker for crips … And any son of a bitch who has been hit solid.” Like Lt. Henry in A Farewell to Arms, Cantwell hates war monuments that conceal intestine-strewn slaughter with high sounding words.

Cantwell is pretty grouchy about the world as he finds it: American women, his anger at demotion after a recent battle failure (probably Hürtgen Forest), his lingering disillusionment with the first Great War when (like Hemingway) he was badly wounded on the Italian front. He meets every aging man’s fantasy girl, Renata, an Italian countess who makes his damaged heart turn over. It’s his last, only, true love. Along the way, while duck hunting and sharing war memories with various Italian stock characters and his long-suffering driver, Cantwell calls Renata “Daughter” while she calls him “Papa.” Most of the story is told in flashback on Cantwell’s last living day.

It’s a struggle to take Across the River seriously. It was first serialized in, and possibly written for, Cosmopolitan magazine. There’s a jarring clash between his old clipped, terse style and the slow, requiem mood of the story. (He’d soon make a correction course in The Old Man and the Sea and brilliantly in A Moveable Feast.) If you dig for it, Across the River is a Lear-like raging take on life, an elegy to young love in old age, a revisiting of the famous code of heroic stoicism, with pride in the soldier’s killing trade and a love for the stunning environs of Venice. But it’s hard at times to get past Cantwell’s didactic preaching to Renata and all the self-pity. He recalls old battles to Renata and connects his emotional state with a war-ravaged landscape. Thus, “I feel as though I were out on some bare-assed hill where it is too rocky to dig, and the rocks are all solid but with nothing jutting, and no bulges and all of a sudden instead of being there naked [without cover or concealment] I was armoured.”

Note: maybe I’m a bit prejudiced about Cantwell because he keeps putting down his GI corporal driver as one of the “over-fed and undertrained” men in uniform. He’s describing me when I was a 19-year old soldier. To be fair let me quote the Chicago-born Jewish critic Isaac Rosenfeld whose larger heart embraced both the good and the bad in Hemingway. “ [Across the River and Into the Trees] is the most touching thing Hemingway has done. For all the trash and foolishness … he gave away some of his usual caution and let a little grief … come through his careful style. A little of the real terror of life in himself, with no defenses handy.”

A final word about Across the River from one of my favorite (if very right-wing) writers, Evelyn Waugh, himself a war vet. “Why do [the critics] hate him so? … the truth is that they have detected in him something they find quite unforgivable—Decent Feeling … behind all the bluster and cursing and fisticuffs …” Hemingway had great hopes for the novel. “I’m crazy about the new book. I’d go hang myself if I thought it wasn’t better,” he told his editor Tom Jenks at Scribner’s. He was stunned by the critics’ blasts, lashing and crashing about him like a wounded bull.

If you have a strong stomach read “How Do You Like It Now, Gentlemen?” Lillian Ross’s 1950 interview-hatchet job in The New Yorker, from the same year as Across the River, where she scrupulously records his ranting and roaring, in pseudo-Native American diction, about how great he is. The amazing thing is that even though Ross cut him to ribbons simply by quoting him, they remained friends. But it set in concrete an image of the writer as a ludicrous fool too full of himself. Perhaps that’s why he was compelled to do a “serious” book like The Old Man and the Sea for his next project.

Hemingway constantly used and misused boxing metaphors and liked comparing himself to a prizefighter. (He was a dirty fighter. Once, sparring with the New York Yankees pitcher Hugh Casey, he kicked Casey in the balls for having the effrontery to knock him to the canvas.) After taking a terrific shellacking from the critical “lice,” he came off the canvas with a hugely popular commercial success, The Old Man and the Sea. He was back on top of the mountain from which he’d taken such an inglorious tumble.

The Old Man and the Sea (1952) won both Pulitzer and Nobel prizes and, in my opinion, is his worst novel. Soft and sentimental, it violates all the important rules of keen, realistic observation of nature and human beings that Hemingway laid down for himself and to which he spent his life trying to be faithful. It’s disturbing that he didn’t know how hollow the book is. In part I blame the celebrity virus that ate him up even as he was enjoying the disease that was helping to kill him. As his son Jack said of his dad, “The fatal word is fame. I don’t think it’s kind to people.”

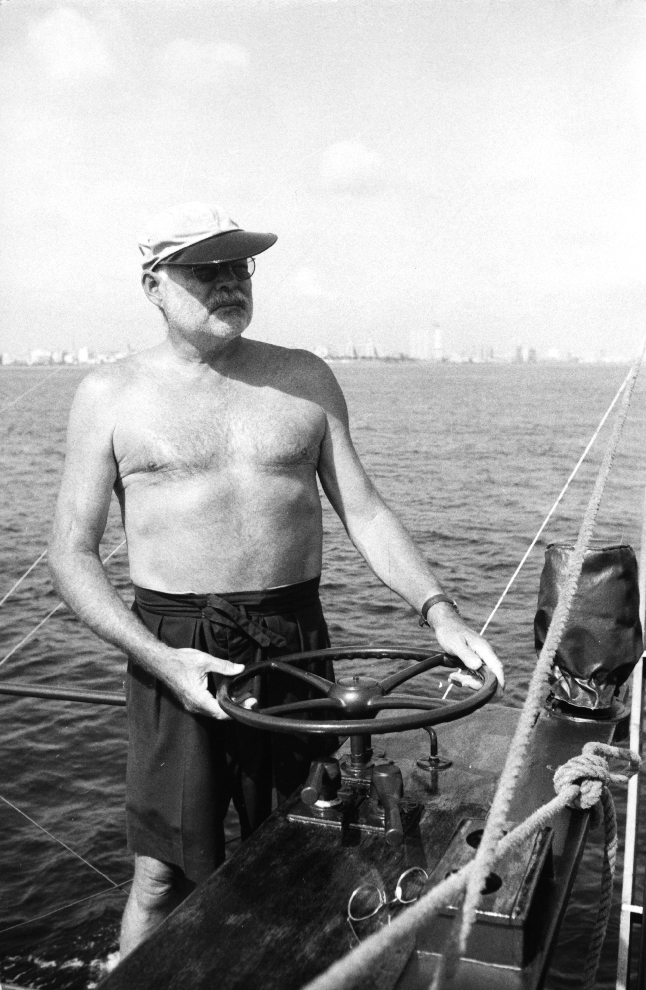

Hemingway drives the boat in Cuba

Hemingway saw The Old Man as a triumphant culmination: “I had gotten finally what I had been working for all my life.” He claimed he’d put everything he knew about life and literature into it. That’s a heavy load for a single short piece of writing to bear. The book is immensely popular even today. As is well known, it’s about a “simple” yet profoundly wise and clairvoyant fisherman, Santiago, a Spanish immigrant to Cuba who has gone eighty-four days without a catch. The village sees him as cursed with bad luck, which is also how he sees himself. Alone, he sails in his skiff toward an epic three-day epic battle with an elusive marlin. When he succeeds in harpooning the big fish it struggles and thrashes and tows him further out to sea, farther than Santiago has ever been. Finally he manages to drag it alongside the skiff. Ay! It’s a huge fish and will bring much money in the market. But, on the return trip back to harbor, sharp-toothed sharks rip his prize to bloody pieces so that all that’s left is a worthless skeleton. At the end Santiago has nothing to show for this struggle but fish bones. However, Hemingway has Santiago emerge as a spiritual victor because, although he lost the fish and his income, he has triumphed over nature, death, and depression. He’s brought back nothing … except a God-like insight that he and the fish are brothers and we are all One with the Sea and Sky.

In this novella there’s a marvelous rhythm that keeps a reader going to the ironic end, a reminder that Hemingway is brilliant at efficiently wrapping up his short stories. The fishing scenes are, as always with this expert angler, full of sharp detail (actually this is more excitingly done in Islands in the Stream). The story has its basis in an article he wrote for Esquire fifteen years earlier, “On the Blue Water,” about an old fisherman who loses a big fish and ends up insane and weeping—not quite an end full of the Christian or existential “meaning” that the author wanted for the novella (my own hunch is that it’s all about the author and his bloodsucking critics, the human sharks tearing away at his prose).

The Old Man and the Sea is as simple with simplicity as a child’s fairy tale and probably should be read that way. In his previous books Hemingway usually respected readers enough to let them make their own connections. But here he relentlessly hammers in Santiago’s agonized reflections. “But man is not made for defeat,” he said (to himself alone on the boat). “A man can be destroyed but not defeated.” In light of recent world history I’d call that a hope rather than a fact.

A famous New York Yankee slugger is Santiago’s patron saint. After he kills the marlin, Santiago reflects, “I think the great DiMaggio would be proud of me today.” To be fair, some serious critics and readers found this story superb, as did the Nobel committee that specifically cited the fishing tale in awarding Hemingway its 1954 prize.

The eighty-six minute Hollywood movie starring Spencer Tracy as the old fisherman is fairly unendurable. Hemingway was on hand to help with the location scenes, in which he and Mary have cameos as American tourists. He loved the movie, much of it shot in a studio fish tank. Tracy was nominated for an Academy Award. In a later made-for-TV version, where a love interest was pasted on, a more plausible Anthony Quinn plays Santiago. Most recently, the Cuban-born actor Andy Garcia has announced he will make Hemingway and Fuentes, about Hemingway’s friendship with his friend and first mate Gregorio, who might have been another inspiration for Santiago in The Old Man and the Sea.