14

HIS SUICIDAL SUMMER

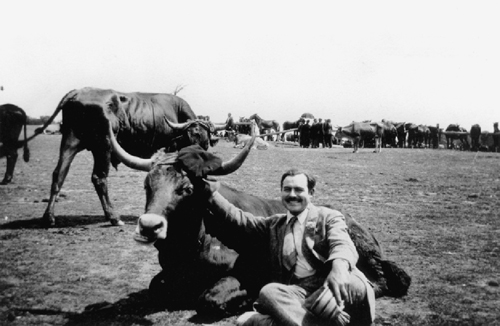

Hemingway with bull in San Sebastian, Spain

Fatally and fatefully, just before his death, Hemingway, who didn’t need the money, grabbed a Life magazine assignment in 1959 to go to Spain and write a series of articles that became, The Dangerous Summer, an epilogue to his 1932 reflection on bullfighting, Death in the Afternoon. He was terminally exhausted as a man and writer but couldn’t stay away from the bullring, in which he had so many times foreseen his own death in the ritual confrontation of matador and sharp-horned bull. Having lost much of his self-control to physical damage, he couldn’t stop writing unprintable page after page.

Part of the temptation for Hemingway was that this was his first trip to Spain since the fascist victory in the civil war, twenty years earlier. Many antifascists had vowed to stay away from Franco’s Spain until democracy was restored, but disappointingly Hemingway let himself be used by the regime as a tourist draw. The main thing I dislike about The Dangerous Summer, once allowances are made for Hemingway’s decline due to age, is that he sucked up to the Franco regime. (My cousin Charlie, like almost all Lincoln Brigade vets, refused to visit Spain until Franco was dead, after which he and other International Brigade volunteers were feted and granted honorary Spanish citizenship.) The pull of the corrida proved stronger than his nostalgia for the murdered Spanish democracy.

True, The Dangerous Summer is a great reporter’s story, covering a series of arena duels in the afternoon between an aging bullfighter, Luis Miguel Dominguín, tired but full of sly tricks, and his young, more naturally talented brother-in-law Antonio Ordóñez during the “dangerous summer” of 1959. Hemingway saw in the drama of Dominguín and Ordóñez his own. For him bullfighting “is the only art in which the artist is in danger of death”—which is how he always saw his own writing: a duel with Death in which the loser is predestined and inevitable. But he drags us into a murkier swamp where bull killing is a profound spiritual experience and very nearly the highest form of life. As Jake tells Robert Cohn in The Sun Also Rises, “Nobody ever lives their life all the way up except bull-fighters.”

Hemingway smiling, with shotgun

The real tragedy is that at this point in his life Hemingway couldn’t put words together without substantial first aid, this time from his loyal pal A.E. Hotchner and Scribner editor, Tom Jenks. Life printed the 45,000-word story in three 1960 issues, and the posthumous book, edited by Scribner’s Michael Pietsch, followed a quarter of a century later. The book had some pretty vicious reviews. A Hemingway biographer called it “vulgar, embarrassing and boring.” The fact is that Papa’s writing always balanced on this fine edge between fascinating and ridiculous.

Nobody knows what external force finished off Hemingway. Illness, injury, a booze-corrupted liver, the inherited Celtic Curse of hemachromatosis, electric shock therapy, or all of the above. Myself, I believe the fantastic struggle he had pruning the runaway words of The Dangerous Summer was the coup de grâce.