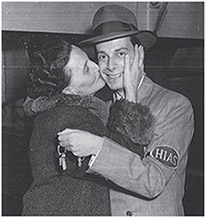

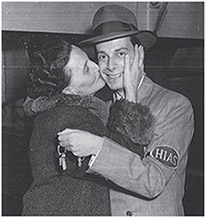

Olga with Simon Mirkin on her arrival in New York, November 1950. Contemporary press photo, courtesy of Barry Mirkin.

OF Mischka’s old friends from Riga and Hanover, only Dailonis Stauvers was at his wedding. The rest had scattered to all corners of the earth or would soon do so. Bičevskis had gone to Australia; others were off to Canada, Chile, Venezuela, Boston and New York. Stauvers himself was probably already planning his departure to the United States, which took place in 1951. The exodus had started two years before Mischka’s marriage, and the Danoses’ correspondence now regularly contained news of friends departing or planning to depart to Brazil, Holland, South Africa and Palestine. Simon Mirkin, Olga’s Riga protégé, was one of the first to go, leaving for the United States in mid 1947. He was able to get in early because he worked for the Jewish refugee organisation HIAS and the American occupation authorities. Olga’s sister Mary was also putting in an application for the United States, the most popular of all destinations for DPs, as were her former husband Paul Sakss and his new wife. Some people had problems with visas and selection by the country of their first choice. But, inexorably, the transient DP communities established in the wake of the war were starting to unravel.

These mass departures were made possible by a new Allied approach to solving the DP problem. The mission of the old international refugee authority, UNRRA, had been to repatriate as many DPs as possible, while looking after those remaining in Europe who were unwilling or unable to repatriate, until someone could work out what to do with them. Political motives were usually cited for the DPs’ unwillingness to return, although undoubtedly many from the East, with its historically lower living standards than Western Europe, had unspoken economic motives as well. The ‘non-repatriables’ included most of the DPs from the Baltic states, Olga’s and Mischka’s compatriots, who did not regard the Soviet Union as their homeland. With their shattered economies, Germany in particular and the European nations in general were not in a position to absorb more than a small proportion of the DPs. The doors to the United States, where many DPs wanted to go, remained largely shut during UNRRA’s reign, and Britain was trying to block movement of Jewish DPs to Palestine, another favoured destination. So for several years after the war, the ultimate fate of the non-repatriated DPs was uncertain.

The IRO (International Refugee Organization), which replaced UNRRA as custodian of the DPs in 1947, had a new plan. This was in effect to give up on the idea of repatriation and move swiftly towards mass resettlement of DPs outside Europe. In 1948, the US Congress passed the Displaced Persons Act providing for large-scale entry, albeit with a complicated system of preferences and restrictions and the requirement that DPs have a local sponsor. Australia, Canada, Argentina and other Latin American countries with labour shortages indicated a willingness to take their share. The system was that DPs recorded their resettlement preferences with IRO but then had to apply to the individual countries and pass a medical, occupational and political vetting by their selection committees. The political vetting was initially to prevent entry of Nazi collaborators and war criminals, but as the Cold War took hold, blocking Communists and Communist sympathisers came to seem equally important.

Olga and, from 1949, Mischka were off the IRO’s ‘care and maintenance’ list as a result of ‘going on to the German economy’, but they were still eligible for IRO resettlement if they cared to take up the opportunity. Whether they wanted to leave Germany and resettle was the first question they had to decide. If the answer was yes, the next questions were where they wanted to go, and which countries were ready to take them.

As Latvians, Mischka and Olga ranked relatively high on the preference list of the resettlement countries, which tended (like the Nazis) to prefer blue-eyed Northern Europeans to Poles and other Slavic groups. Australia, for example, put Latvians right at the top of its mass resettlement scheme, and the United States regarded them as desirable too. The potential problem for Latvians was suspicion of wartime collaboration, particularly by those who had volunteered to fight with the Germans in the Latvian Legion or the Waffen-SS, but the Danoses were not in that category. On the other hand, the preference of most of the receiving countries for young, healthy manual workers did not favour the Danoses. Young professionals and ‘brain-workers’ among the DPs were in less demand as immigrants, even if they had finished their education in Germany courtesy of UNRRA; if they got through the selection, they couldn’t count on getting jobs that fitted their qualifications, and some found it advisable to fudge their biographies and present themselves to the selection committees as builders’ labourers or domestic servants. Older professionals, especially those in less than perfect health, were often shunned by selection committees, along with sufferers of TB and syphilis and the disabled. Most selection committees favoured a cut-off age of around forty-five for DP immigrants, which was a potential problem for Olga, who turned fifty in 1947. Fortunately, she had had the forethought to misstate her date of birth from the moment of her arrival in Germany, and managed to lop off a few more years from her IRO documents.

Olga and Mischka, particularly Mischka, belonged to the relatively small number of DPs capable of supporting themselves, currently and in the future; for them, remaining to make a life in Germany, or perhaps elsewhere in Europe, was a plausible option. You might expect that they would have considered this seriously, particularly in view of their linguistic skills, Mischka’s marriage to a German girl and Olga’s unwillingness to accept the separation from her sons in Riga as final. Yet there is no sign that either of them did so.

This is a bit of a puzzle. Once he moved to Heidelberg as Jensen’s assistant, Mischka’s best chance of a future as a physicist, particularly a professor of physics, lay in remaining in Germany. We have no direct evidence of his attitude to the Federal Republic, established the year he went to Heidelberg, but he thought very highly of the currency reform (Währungsreform) of 1947 that paved the way for West Germany’s rapid economic recovery, and continued in later life to cite it as a rare case of dramatically and instantaneously successful state economic intervention. As he remembered,

Before the Währungsreform, trains, trams incredibly overcrowded, like in India; people were pushy, impolite, crude, aggressive, thin-tempered, etc. … First day of DM [Deutschmark]: after getting my DM-s, I invested in a month tram-pass, which was indispensable for getting around: to school and to sports club. It was a reasonable fraction of my capital. I entered the tram. Surprise: nobody pushed, no foul language; instead: everybody polite, soft spoken, civilized. Seats available. Strange. Same on street: instead of milling, jostling crowds, polite pedestrians; instead of store windows yesterday empty and bleak, same today filled with goods with prices attached, and prices reasonable, even though nobody actually could buy much, except perhaps somebody representing a large family. Within some days, as more and more people got their salaries, the economy began moving, and that was the beginning of the Wirtschaftswunder [economic miracle].

To be sure, arguing against remaining in Germany was Mischka’s new anti-Germanism, which led him to write critically of the German national character, refer to the country and its occupants as ‘Germanium’ and ‘Germanen’ (not with the German words ‘Deutschland’ and ‘Deutsche’), and to say later that he couldn’t have stayed in Germany, for all the appeal of Heidelberg’s Tea Colloquium, because of his feeling of ‘pressure’ there. This pressure evidently arose from a sense of constraint and tension; he expressed it to me later as not being able to breathe. This was a physical description, not a psychological one, but when pressed on the psychological basis, he invoked something like the theory of ‘authoritarian personality’ popular among postwar American social scientists, including psychiatrists sent to work in the American zone of Germany to uncover ‘Nazi personalities’ as part of denazification. ‘The German alternatively commands and scrapes,’ one of these psychiatrists explained; ‘this is obvious in the family, where the father, dominating his wife and children, no sooner leaves the house than he bows to his superiors.’ Fascist personality traits were to be expected ‘among children with stern, often physically abusive fathers and distant, frightened, and unaffectionate mothers’. Misha’s 1995 analysis runs along similar lines, with the addition of his favourite epithet for German behaviour, ‘rigidity’, and inclusion of the tendency to watch for and officiously correct non-conformist behaviour on the part of others.

Olga did not express anti-German sentiments in her letters, though Mischka assured Helga that she shared his strong hostility to German nationalism. Given her firsthand experience of the problems of small business, she may have been less sanguine than Mischka about the future of the German economy. On the other hand, she was not at all confident about her personal prospects elsewhere, especially in the United States, imagined in Europe as ‘a big factory populated with heartless robots’.

Perhaps the basic reason the Danoses felt, more or less unquestioningly, that they had to leave Germany was psychological. It would have been hard, even for such independent thinkers, to stand confidently against the tide that was pulling hundreds of thousands of DPs out of Central Europe, especially as the pace stepped up dramatically in 1949. By mid 1949, more than half a million had gone (out of an original million or so DPs), and a year later the number of departures had almost reached 800,000. Moreover, assisted departure was not an option that was going to last for ever. The IRO, mainly US-funded, was expected to get the job done within a few years and go out of business, and the US Congress was becoming impatient. In fact, the IRO stayed in operation after several deferments of closure (Olga and Mischka periodically exchanged anxious news of the latest developments), but the prospect of its imminent demise, along with the organisational help and free passages it offered, created its own pressures (What if the last boat goes without me?). By the time the IRO actually ceased operation at the end of 1951, only a ‘hard core’ of fewer than 250,000 DPs remained in Europe (not just Germany, though the largest group was there). While a minority were employed, like the Danoses, in the German or Austrian economy, the majority were rejects—persons with ‘paralysis, missing limbs, or a history of TB’, along with convicted criminals and the elderly—left at the mercy of the new Federal Republic and charitable organisations because no country would take them.

If departure was on the agenda, the next question was where to go. Olga’s original preference was for Latin America, and she registered Argentina with the IRO as her preferred destination in 1948. She already had contacts there, probably from earlier DP departures, and thought the language would be easier to master, since she knew Italian. Earlier, back in the Hanover days, Mischka had not been wholly against the Argentinian option, going so far as to ask Jensen if he had any contacts there (Jensen did, at the National University of La Plata in Buenos Aires, and said he would write to recommend Mischka). But by mid 1948, Mischka was categorical in his support for the United States option and opposition to Latin America. ‘I still see no substantive grounds for your desire to go to South America,’ he wrote brusquely to Olga, adding that he regarded the language as a minus, not a plus (admittedly, his Italian was not as good as hers) and learning Spanish an unnecessary complication. (He was, in fact, increasingly focussed on improving his English, practising it in his letters to Olga—‘I do not need any mony [sic]. And do not bother about me!’ is an early effort.)

Olga had another go at explaining her reasons, with no more success than before:

Look, Mischutka, I am simply frightened of the US. Life there demands too much shoving for my taste. And I don’t see the remotest possibility of remaining independent, just maybe working in a factory. South America is not so feverish, and I hope there to have a chance to establish myself.

At this point, Olga was so set on Argentina and hostile to the United States that she was willing to contemplate their emigrating to different destinations, writing that ‘if you go to the US and see some possibility for me there, then I could always move. But perhaps I would also be able to do something for you in Buenos Aires.’ As late as September 1948, Olga was still thinking in terms of Argentina and saving her money for an application to the Argentinian consulate in Frankfurt: she was so fed up with Germany that ‘if it had been possible, I would have jumped on an aeroplane and flown to South America’. Still, she was hedging her bets to some extent, encouraging Mischka to put his name on a new register of DPs qualified for university jobs in North America and urging him to ‘please, really please, do everything that I don’t know but you do to make your scientific work accessible and transportable’.

Regardless of destination, Olga was becoming increasingly dissatisfied with her situation in Germany. The high hopes she had had for her sculpture when she moved to Fulda seem to have been disappointed, at least until shortly before her departure. Although in a later interview with an American newspaper she described her occupation in Germany before her departure as ‘mending religious figures from bombed out German churches in Frankfurt-am-Main, Wiesbaden, Bremerhaven and other cities’, there is almost nothing on this subject in her letters of 1949. Much more space is devoted to discussion of her tailoring business and money troubles.

The tailoring business looked good on paper, but in her letters it comes across mainly as a burden. There were reports of trouble with angry customers when she was ill and couldn’t summon the energy to finish a job (it is not clear why she was doing the sewing herself, but it was possibly alterations on work done badly by her employees). There were also indications that the tailoring connected her with a grey barter economy: early in 1949, she reported visiting a general’s wife in Wiesbaden who gave her some material to make up but also took $10 and two cartons of cigarettes from Olga in exchange for a man’s jacket (for Mischka). Problems with tenants in the house she was living in also feature quite prominently in her correspondence; it looks as if she may have been in charge of supervising the house and letting other apartments on Mirkin’s behalf. When she fantasised about flying away to South America, it was because ‘I wanted money so much, to earn a lot of money. Perhaps a more normal time will come sometime.’

Fulda didn’t feel like a proper home, she wrote to Mischka. Apropos of the question of emigration destinations, she commented:

However it comes out, I would like to get away from Fulda. It is odd that even though now I have a house, I can’t settle down. When I would get back from my trips to Flensburg, Glücksburg, even my hotel room in Reichenberg, I felt as though I were coming ‘home’. But not here. Often I tell myself that I will probably end up having to stay here—just for that reason.

Olga came down finally in favour of the United States. Her only direct statement on the decision was written years after, when—in still fractured English, so probably not too long after her arrival—she recalled that ‘after long hesitation I had given in my friends and his wifes repeated persuasians, to come to America’. The friends were probably Simon Mirkin, newly settled and employed in New York, and his new wife Ilse, also a DP. What seems to have tipped the scales for Olga was Mirkin’s offer to sponsor her. The United States, unlike most other resettlement countries, required immigrants to have a sponsor even if they came in under the DP Act of 25 June 1948, which authorised the admission in the next two years of 200,000 DPs for permanent settlement. This sponsor might be a charitable, religious or ethnic organisation (Mirkin’s own sponsor had been his employer in Frankfurt, HIAS), or it might be an individual. No actual invitation from Mirkin survives, but he identified himself as her sponsor in a statement to the press on her arrival, and explains his sponsorship as an act of gratitude to her for saving his life. There is documentation of his subsequent offer to sponsor Mischka. By the end of 1949, in any case, Mirkin’s involvement in Olga’s departure plans are taken as a given in her correspondence with Mischka. She now thought she might get to America quicker than her sister, who had applied earlier, since ‘Mirkin is sending me the work contract’.

Right up to the moment of departure, however, Olga showed little positive enthusiasm for her chosen destination, or even for departure as such. Her mood in 1948–49 was depressed, and this showed, rather uncharacteristically, in her letters to Mischka as well as her diary. ‘Mischutka, I’m getting old,’ she wrote in July 1948. ‘Since I heard of Papa’s death, I look backwards more than forwards.’ The next winter, around the time that Mischka was making up his mind to marry Helga, her mood was even lower, at least judging by a letter written to him but never sent. Having started by thanking him for a letter (‘You can make someone so happy with a few words’), she plunged immediately into a demonstration that his letter had not, in fact, had this effect:

You are one of those I love most [but] we shouldn’t stay together … No, we shouldn’t. I mean to let you go. All the people who depended on me, I brought them unhappiness. I will not at any cost give you advice. Everything I have done has been bad. I can’t get rid of the thought that the two letters I wrote to Riga [after receiving Arpad’s letter] have brought misfortune to the young ones [Arpad and Jan]. All my efforts to turn my thoughts in another direction don’t help the pain. If it could help, I would kill myself. But I don’t believe in that kind of magic … Dear, dear Mischutka, I won’t send this letter. But I’m going to pull back from you all the same, doing it so that you don’t notice. I have to spare you that at least. What a flood of nonsense is pouring out. It’s nothing but egoism …

I was quite upset when I read this letter (late in the game, when I had already written the first draft: it was a fragment in untidy handwriting that looked hard to decipher). No, you didn’t bring unhappiness to Misha, I wanted to tell her. On the contrary, you were a lifelong support and inspiration to him; if only everyone had such a mother. But this would have been a message from Misha’s wife rather than his biographer. Of course Olga was too sensible and too protective of Mischka to send her anguished letter; she kept such emotions for the diary and the drawer. And, being the resilient person she was, she coped.

It’s tempting to speculate that one of Olga’s strategies for coping with a partial loss of Mischka through marriage was to find a substitute. Daniel Kolz, a young pianist about Mischka’s age, first appears in the correspondence in a rather strained and arch letter to Mischka and Helga about the wedding, which it appears Daniel had attended, though not officially as Olga’s companion. In this letter, Olga makes much of the remarkable resemblance of Mischka in his wedding photos to Daniel, which she and Daniel had marvelled at. Thereafter, Olga’s letters regularly contain news of Daniel’s career, and Mischka’s letters include friendly enquiries about him (Mischka and Helga also kept in touch with him for years after they had all moved to America). Olga was still an attractive woman, and whether Daniel was just a protégé or also a lover is open to question. At the time, Helga recalls, it did not occur to her that they were lovers, though in retrospect she thought they probably were. If it occurred to Mischka, no trace remains. In any case, Olga and Daniel provided each other with support, emotional and practical, and evidently enjoyed each other’s company. The most buoyant letter in Olga’s whole correspondence in the Fulda period describes a celebratory dinner with other friends that Olga and Daniel had organised on the spur of the moment after some success of his. ‘You have a really young mama-in-law!’ was her final cheerful comment to Helga.

Kolz was also no doubt partly responsible for the growing prominence of music in Olga’s and Mischka’s letters. They had always exchanged occasional reports of music they had heard in concerts and on the radio, but in 1949-50 the frequency and seriousness of these reviews became such that they might have been professional music critics. Probably it wasn’t only Kolz’s arrival on the scene but also Helga’s that produced this result: music was the main thing the four of them had in common. But they weren’t the only ones in Germany to whom classical music mattered. It mattered so much to the German population as a whole that even the Allied occupiers noticed. ‘If ever the beasts of war are tamed, it will be music which will grant us the strength of heart and soul to do it,’ as one official of the American military government put it.

Hoping to bring out the Germans’ better side, all the occupying powers, including the Soviets, competitively encouraged live performances and supplied more on their zonal radio stations. Naturally there were some political complications, particularly with regard to performers: the Nazi leaders had also liked music, as long as it wasn’t modernist and degenerate. The pianist Ellen Ney, a Beethoven specialist and sometime favourite of Hitler, was on the blacklist in the American zone until 1948, her concertising limited to ‘atonement’ concerts for American troops, POWs and DPs. The great pianist Walter Gieseking had problems too. He had not been a Nazi party member but, because of his visibility as a performer in Nazi times, was widely regarded as a collaborator. The Americans had him on their blacklist until early 1947, although the French allowed him to teach and perform freely in their zone. When he went to play Carnegie Hall in New York in 1949, immigration officials swooped in, following noisy public protests, and he had to leave the country swiftly under threat of deportation.

The Danoses both went to Gieseking’s concerts in Germany that same year, Olga in Frankfurt and Mischka in Heidelberg. They went to those of Ellen Ney, too, as well as a whole string of other pianists and string quartets, all thoughtfully reviewed. Neither Olga nor Mischka showed any sign of being interested in the political controversies; they went to Gieseking’s and Ney’s concerts for the music. So, incidentally, did my father and my eleven-year-old self when Gieseking came to Melbourne in 1952 (there was controversy about the visit in Australia too, but my civil libertarian father was against boycotting musicians for political reasons). Olga was a bit critical of Gieseking’s Debussy (the composer was something of a Danos specialty, his art songs being prominent in Arpad Sr’s repertoire) and so, I must admit, was I, when he played all twenty-four Préludes at one sitting in Melbourne, putting me off Debussy for decades.

Mischka had splurged a back-pay windfall to buy a Philips ‘Philetta’ radio ‘with very good sound quality’ to listen to music. He had it on while writing a letter to Olga, and his attention was suddenly diverted to a broadcast of Bach’s Chromatic Fantasy and Fugue: it reminded him how extraordinarily modern Bach was (he offered a brief technical analysis); there was nothing like it again until Hindemith. Mischka, but not Olga, quite often mentioned Paul Hindemith in his commentaries on music. His exposure to Hindemith—a German modernist composer who had emigrated in the 1930s—was no doubt thanks to OMGUS, the propaganda arm of the US occupation forces, which was pushing modern music and abstract art on the Germans on the slightly bizarre premise that as the Nazis had labelled modernism ‘degenerate’, it must have some intrinsic connection with democracy.

When Olga first started taking serious steps towards departure in the summer of 1948, she was still thinking in terms of Argentina. She went through her IRO screening for emigration eligibility at the end of July, and was planning to go off to Frankfurt to register with the Argentinians as soon as she had enough money. Her emigration number came through early in 1950, with the United States replacing Argentina as her destination. But there was a problem with the birthdate registered in her papers, of which the police had informed her a few weeks earlier. In April she wrote to Mischka that her papers were going through IRO, but she was so fed up with all the problems that the night before, on the eve of the final submission date, she had ‘toyed with the thought of having to give up the whole emigration’. The main problem seems to have been that her documents showed an earlier birthdate than 1905, and she was insisting on a correction with as much outraged determination as if she had actually been born then, and not in 1897. In the end, by going over the head of a junior official to a senior one, she had her way. These arrangements were evidently all being coordinated with Mirkin in New York, but that correspondence is lacking. Once Olga had been approved on all sides as an immigrant to the United States, control left her hands for the time being: she just had to sit and wait until the IRO told her to proceed immediately to the transit camp prior to embarkation on such and such a vessel.

But then came a new complication: Olga fell ill. There was a sore spot on her stomach, and she booked in for an X-ray. She was worried about the cost of the medical visits and treatments, however, so when the doctor wrote her an expensive prescription, she ignored it and went to a homeopathic medicine man. Surely it would soon get better—but in the meantime, things were ‘very bad in terms of my mood, and so it’s a blessing that nobody from my nearest and dearest is around. I don’t know how to put up with being sick with elegance—I mean spiritual elegance.’

It turned out that she had to have an operation. ‘I was bleeding uninterruptedly for almost a month and waited to go to a doctor until it stopped. Some days it was so strong that I could scarcely stand.’ When she finally did go to the doctor, he insisted on putting her in hospital; ‘it would have been better to put it off’, as she wrote to Mischka, ‘[but] I have to let them cut my belly open, and better soon than later. I have already made arrangements with the butcher and now am just waiting for some money that should come through in a few days.’ The operation took place in the Herz-Jesu Hospital in Fulda around the third week in June, and she expected to be in hospital eleven days. She woke up from the operation hearing snatches of Beethoven and thinking it was her son Arpad bending over her. As she reported to Mischka and Helga, ‘the scar is over the whole belly. I think he must have pulled my entire innards out …’

Not only was this operation incredibly badly timed, since she was likely to be summoned for emigration any day, but it was also a major blow financially. Olga had been trying to save up to cover departure expenses, but all that was gone, and Mischka was called on for an urgent contribution. Even that didn’t cover all expenses for the hospital stay and medical treatment, and Olga had to persuade the surgeon to allow her to send the final payment later from America.

Her summons to the transit camp in Butzbach (north of Frankfurt, about 100 kilometres from Fulda by road) must have come not long after she got out of hospital, or conceivably even earlier. She was in Butzbach by 31 July, arriving by train and then walking to the camp. On the way, she sat down on a hillside overlooking the forest and remembered how seven years ago (surely six, in fact) she had sat on just such a hill in Gotenhafen and looked over the sea to Sweden, where she wrongly thought her sons Arpad and Jan had found refuge: ‘Today I have nothing to look for.’ She was ‘miserable as a dog’, she wrote to Mischka. ‘I don’t know why I have to go to America. And yet I am going to do it. Without inner conviction but out of some kind of [illegible word—Muk?]’. Perhaps it’s appropriate that that key word is illegible. Was it courage (German Mut) that was driving her on? Or torment (Russian muka)? Or something between fatalism and a stubborn determination to finish something she had started?

Before embarkation she spent a couple of months based in Butzbach in a remarkable whirl of activity. She seems to have been almost constantly on the road, attending to urgent business, and wondering why, in her life, everything always had to be done at the last minute. Fortunately, her health held up, so that she could write bravely to Mischka in mid September that

the stomach wound has healed well and peace reigns in my intestines. Now fortunately there is no discharge. The only thing is that my resources are at this moment only half a [Deutsch]Mark. It’s also a bother that I have to travel so soon after such an operation … Things are better with me again. Who could take this joke [i.e. the illness and operation] seriously!

One set of last-minute business was of a legal and financial character, some of it evidently connected with the settling of affairs with regard to Mirkin’s house in Fulda. The outcome as well as the substance of the matter (or matters) are unclear: in an undated letter probably written in August, she rejoiced that after ‘endless correspondence’ between Fulda, Kassel and Frankfurt (where the lawyer was), the affair had been settled in her favour and ‘I have finally become rich’. But evidently she spoke too soon, since the next month there are references to ‘my Kassel disappointment’ and the fact that Helga’s mother had been kind enough to offer her a loan, ‘which I accepted with great relief’. In any case, it’s clear that with regard to the business matters, she left a lot of loose ends still dangling, which Mischka and Helga had to tidy up after her departure.

Some of her pressing business was related to emigration. Despite her efforts to postpone it, she had to go through medical inspection in August; rather surprisingly—you would think a recent major operation might have hit alarm bells—this went without a hitch. She was running around various local and American commissions and the Fulda police collecting and delivering documents. And on top of that, she was constantly trying to find time to get to Heidelberg for a final visit, though it looks as if she never managed it.

The most remarkable aspect of Olga’s departure was that in these last months in Germany, her activity as a religious sculptor suddenly went into high gear. In mid September, she wrote to Mischka that with perhaps two weeks remaining before her departure, she had begun some sculptural work for the church in Fulda and was now trying desperately to finish it. If only the priest would let her work late into the night, but unfortunately he slept just above the church cellar in which she worked. So she was having to stay on for some extra days but hoped to be able to leave on 22 September. ‘You can imagine that I absolutely must finish my big “Work”.’ Art experts, including the sculptor Richard Maur, with whom she had had some contact back in Riga in the 1920s, had come to see her figurines, notably a St Antony holding the Child Jesus in his arms, and praised them. Olga was pleased by their positive reactions, but even more (she said) by the fact that when she told Maur that she had described herself to fellow Latvian DPs as his pupil, which was not strictly true, he had said she had every right to do so and he would be glad to be seen as her teacher.

Mischka was drawn into the last-minute appraisal of Olga’s figurines too, and sent a remarkably detailed critique, noting a fault in one of the pleats in St Antony’s sleeve and that the Child’s face was too grown-up for his body. Olga was still working hard, especially on the Child (she had sculpted him naked but was now, perhaps in response to Maur’s suggestions, clothing him). On the eve of her departure for the embarkation camp, she was thinking almost exclusively about her sculptures, dashing off a note to Mischka and Helga defending her vision of the Child as ageless in terms of Catholic tradition. She was sending the figurines (evidently St Antony and the Child) to them in Heidelberg and regretted that she couldn’t send them her Holy Family as well—they would find Joseph ‘particularly amusing’, she thought; the figure was a bit stiff, but she was just going to have to leave him like that. ‘Despite all the mistakes … I am satisfied in the highest degree that I have made him.’ In a final postcard sent off the next morning, she was still obsessing about the sculptures, tormented on her last night by dreams that she had done St Antony’s pleats wrong.

She had received her embarkation notice on 13 September (‘the thirteenth: is that a lucky or unlucky number?’), with instructions that she would be departing in eight days. Meanwhile, there was another mishap: she fell when getting out of the train in Butzbach and injured her leg. She hoped this would get her an extension, and indeed she was able to add in a postscript: ‘Extension until 28 September. On the way to Frankfurt. Oh-oh-oh-oh! Such anxiety!!!’

Olga’s actual embarkation date was Sunday 22 October 1950, so her ship’s sailing date was probably postponed at the last minute. The next we hear from her is a letter from the middle of the Atlantic Ocean en route to New York giving a rather harrowing, though unself-pitying, account of the trip. She was on a troop ship filled with DPs, allocated a top bunk— just under the light and the ventilation, which Olga reports as a positive—in a corner in a hall accommodating 500 people in tiers. The IRO had given each passenger $1.50 to spend at the PX on board, and Olga had used it to get stamps to send her letter from Halifax, their first North American stop. Shipboard conditions were obviously awful, with fetid air, and pushing and shoving at meals, and vomit in the gangways. On deck, there were seats for only about fifty people; when it rained, the only shelter was under the lifeboats that were hanging up. Nevertheless, after a terrible twenty-four hours of intense seasickness during a storm in mid-ocean, Olga spent most of her time there, if not lying and writing in her bunk: ‘I always stand at the railing or—if it is frosty, sit on the rolled-up rope ladders and look for hours at the water and the sky,’ wearing two jackets and her fur coat.

As the ship approached New York, the passengers were allowed to stay on deck all night to get a first sight of the city, but Olga went to bed, rising on 1 November at four—half an hour before breakfast—to see the Statue of Liberty—or rather, not to see it, since it was obscured by ‘night and cloud’. It took an hour for the tugs to pull them in, in which time New York’s skyscrapers became visible. She was one of the first through medical control, and as she was waiting for immigration to open, Mirkin appeared. He had promised to meet the ship, but still it was a big relief to see him—‘he didn’t look so ugly any more’, as she commented in her report of the arrival sent to Germany. She didn’t enjoy it, however, when he insisted on parading her before the crowd of reporters and photographers gathered to write their DP stories. Instructing her to leave the talking to him, ‘Mirkin gave them a whole novel (Roman)’ about her and their past connection, Olga wrote wryly to Mischka and Helga. This is how the Spokane Daily Chronicle reported Mirkin’s story:

A 29-year-old Jewish refugee paid a debt of gratitude to a Christian woman who sheltered and befriended him when the Nazis overran his native Latvia.

The story began in Latvia in 1941.

Simon Mirkin, his young sister and their parents were clapped into a German slave labor camp for Jews near Riga. During a trip to Riga on a labor project, Mirkin met Mrs. Olga Danos, 44, Russian Orthodox, who made her living as a dressmaker for the wives of Nazi officials.

Mirkin said that, through a bribe, Mrs. Danos arranged for him and his family to live with her. They were released from camp and made their home with the dressmaker for two years.

After the war Mirkin married and came to the United States. But he never forgot his benefactress. Today, Mrs. Danos arrived by ship as a displaced person—sponsored by the Mirkins, with who [sic] she will live.

‘I want to return to her just a little of what she had given me by helping her to start in the United States,’ Mirkin said after greeting Mrs. Danos at the pier.

This was indeed a touching and uplifting story, though perhaps one shouldn’t take it too literally, given Olga’s comment on Mirkin’s ‘novel’. Since the Danos family knew very few details about Olga’s activity saving Jews, I had always hoped that if I could ever track down some Mirkin descendants, they would know. And finally I did track down Barry Mirkin, thanks to Olga’s noting the name of the toddler who damaged one of her letters to Mischka shortly after her arrival in New York. He did indeed know about Olga and how grateful his father, recently deceased, had been to her for saving him. He sent me the press cutting and the photo of the two of them together on her arrival. In crossing emails, each of us eagerly asked the other for details about exactly what had happened in Riga and just how Olga had saved Mirkin and other Jews. Alas, neither of us knew. Now, I suppose, nobody ever will.