33

What can corpora tell us about English for Academic Purposes?

Averil Coxhead

1. What can corpora reveal about aspects of academic language in use?

In his book, Better: A Surgeon’s Notes on Performance, Atul Gawande urges professionals to ‘count something’. He reasons, ‘If you count something you find interesting, you will learn something interesting’ (Gawande 2007: 255). Corpus linguistics has contributed a great deal to English for Academic Purposes (EAP) precisely because researchers, teachers and students now have access to computer-based tools that enable them to systematically ‘count something’ in the language they encounter in their academic studies. Counting draws attention to features of the language that might otherwise have been ignored. It also addresses two problems for teachers and learners. The first is that intuition has played a major role in deciding what to teach and what to include in EAP materials. The second is knowing what language is problematic for EAP learners. This chapter on EAP and corpora addresses five questions: what can corpora reveal about aspects of academic language in use; how can corpora influence EAP pedagogy; how can corpora be used in EAP materials; what can a corpus tell us about EAP learner language; and what might the future be for corpora in EAP?

EAP is about teaching and learning English for students who speak English as an additional language and who are studying or preparing to study at undergraduate or postgraduate level. It is important to find out more about academic language in use because, as Gilquin et al. (2007: 321) point out, ‘The distinctive, highly routinised nature of EAP proves undeniably problematic for many (especially novice) native writers, but it poses an even greater challenge to non-native writers.’

Corpus linguistics research has brought to light interesting and at times puzzling data on academic language in use. Gilquin et al. (2007: 320) summarise the contribution of corpus-based studies to EAP by saying they have provided ‘Detailed descriptions of its distinctive linguistic features, and more specifically its highly specific phraseology, and careful analyses of linguistic variability across academic genres and disciplines’.Itis important to remember several key points about academic language that EAP students study and EAP teachers teach. First of all, it is not just written, but it is also spoken. Second, it is not just produced in published form by academics in books and journals, but it is also produced by native and non-native students in the form of essays, reports, theses, as well as PowerPoint and tools such as WebCT, and more. Third, even though there are more and more EAP-focused corpus-based investigations, we still have a great deal more to count, analyse and learn about academic language in use.

The number and size of EAP corpora have boomed somewhat since the early 1990s (see Thompson 2006 or Krishnamurthy and Kosem 2007 for lists of existing EAP corpora; Flowerdew 2002 and McEnery et al. 2006 for their survey of corpus resources). Some EAP corpora are publicly available, such as the Michigan Corpus of Spoken American English (MICASE; Simpson et al. 2000), the British Academic Spoken English corpus (BASE) and the British Written Academic corpus (BAWE) by Nesi and Thomson. Some corpora contain both written and spoken English, such as the TOEFL 2000 Spoken and Written Academic Language Corpus (T2K-SWAL) (Biber et al. 2001), while others focus on learner language such as the International Corpus of Learner English (see the work by Granger and her colleagues at the Catholic University of Louvain, Belgium). Mauranen (2003) reports on a spoken corpus of English as a Lingua Franca and various studies such as Thompson (2006) and Hyland (2008) examine both learner and native speaker written academic output.

Deciding what to put into an academic corpus, in what proportion and why are not easy decisions. The T2K-SWAL corpus, for example, contains a wide range of academic written materials, including textbooks, university brochures and catalogues, whereas other corpora focus on one kind of output such as PhD or Master’s theses. Size is an issue in corpus development also and corpus-based EAP studies have been based on small corpora (see Flowerdew 2001) through to reasonably large corpora such as the twentyfive-million-word Hong Kong University of Science and Technology corpus of secondary and university essays (cited in Krishnamurthy and Kosem 2007: 360).

Vocabulary has been a major area of corpus-based research into academic language. Word frequency lists that would have taken many researchers many hours and years to compile in the past can now be generated using programmes such as WordSmith Tools (Scott 2006) and by teachers or learners working online using websites such as the brilliant Compleat Lexical Tutor by Tom Cobb. See O’Keeffe et al. (2007: 200–3) for a very accessible description of frequency in written academic English. Word lists have been developed such as the Academic Word List (AWL, Coxhead 2000; see also an investigation of the AWL in medical English in Chen and Ge 2007), a Business word list, (see Nelson n.d.; Konstantakis 2007), and a pilot Science-specific EAP word list (Coxhead and Hirsh 2007). Work on how words behave differently across academic disciplines (Hyland and Tse 2007) reveals further aspects of academic language that are useful for a variety of teachers and learners in an EAP context. Early studies of ‘technical’ or ‘semi-technical’ language pointed out that words such as cost take on specific meaning in Economics that they do not have in general English (Sutarsyah et al. 1994). More corpus-based work on the common collocations and phrases of the AWL words is underway (Coxhead and Byrd forthcoming).

Analyses of textbooks have become more common in the EAP literature. Gabrielatos (2005) states that textbook corpora allow us to examine language that our students are exposed to in their studies and can lead to more pedagogically sound materials (see McCarten, this volume). Comparative studies of textbooks and university classrooms (Biber et al. 2001, 2004; Conrad 2004; Reppen 2004) have shown consistently how textbooks could be enhanced by the application of corpus findings. Conrad (2004), for example, provides a powerful example of how the word though is used in ESL textbooks and in corpora. Conrad also demonstrates how corpora allow us to investigate multiple features of academic language by comparing an ESL textbook practice lecture with five lectures from the T2K-SWAL. Her analysis showed that the face-to-face lectures contained more interaction than the ESL textbook lecture, which in turn was more information-based. Conrad goes on to recommend that teachers and materials designers might consider integrating examples of face-to-face lectures.

The majority of EAP corpus-based studies have targeted university- or tertiary-level adult learners. A recent study by Jennifer Greene (personal communication, 18 February 2008) looks at the vocabulary of textbooks used in middle schools (sixth–eighth grade; ages eleven–fourteen) in the USA to find out more about the vocabulary these learners encounter in context. Greene compiled an eighteen-million-word corpus of English, Health, Maths, Science and Social Sciences/History textbooks.

Researchers have also looked at multi-word units in academic texts. These units have been called (among other names) formulaic sequences or lexical bundles. Examples of multi-word units are in relation to and on the other hand (see Biber et al. 1999, especially Chapter 13 on lexical bundles in speaking and writing; and O’Keefe et al.’s 2007 book for more on lexical chunks). Bundles have been found to be very important for EAP learners. Biber et al. (2004) analyse lexical bundles in university classroom teaching and textbooks and find that classroom teaching contains more lexical bundles than conversation, textbooks and academic prose. The authors present a taxonomy of bundles, including stance expressions such as well I don’t know, discourse organisers such as if you look at, and referential expressions such as one of the most. Scott and Tribble (2006) examine ‘clusters’ in a corpus of postgraduate learner writing and articles from the BNC, while Hyland (2008) looks at variation in lexical bundles across disciplines by examining four-word bundles in Biology, Electrical Engineering, Applied Linguistics and Business Studies in three corpora; research articles, PhD theses and MA/MSc theses. Hyland finds substantial variation between and among the three disciplines. The topic of idioms in academic contexts is covered well in O’Keeffe et al. (2007: 90–4). See also Simpson and Mendis (2003).

Studies into corpora do not necessarily involve just analysing words in spoken and written texts. Ellis et al. (2008) have created an Academic Formulas List by investigating a wide range of corpora including the MICASE corpus mentioned above, finding formulae that fit their selection principles, and asking EAP teachers to discuss the ‘teachability’ of these formulae in classrooms. The MICASE corpus has been the basis of many interesting investigations. The MICASE website is well worth browsing to search the corpus, use in EAP classrooms, and gain benefit from a substantial amount of research and teaching effort. Another example of using a combination of quantitative and qualitative research methodologies comes from Aktas and Cortes (2008) and their study of ‘shell nouns’ in published and ESL student writing.

Special aspects of academic writing have also been explored by various researchers. One example is the Thompson and Tribble (2001) investigation into the use of academic citations in doctoral theses in Agricultural Botany and Agricultural Economics. The authors then investigated citations in EAP student writing and noted differences between disciplines and genres (see also Hyland 1999, 2002 for more on academic citations). Thompson and Tribble go on to show how EAP textbooks do not contain explanations or instances that reflect how academic citations are used in different disciplines within the university and suggest ways in which corpora can be used to fill that gap. Hunston (2002) provides an interesting overview of interpersonal meaning in academic texts and as well as EAP and corpora.

2. How can corpora influence EAP pedagogy?

Some clear benefits to using corpora in EAP have been noted, particularly in the area of second language writing. Yoon and Hirvela (2004) find the learners in their study of the use of corpora and concordancing in their L2 writing classrooms responded positively and felt that they had developed confidence in their own writing. Yoon (2008) reports on a study of six L2 writers using corpora in an academic context and finds benefits such as participants using a corpus to look up lexical and grammatical items that were problematic, raised awareness of lexico-grammatical and language, as well as increased confidence and independence as writers.

Tribble (2002: 147) discusses how EAP students might draw on three types of corpora to support their development as academic writers. He suggests ‘exemplar’ corpora that are specifically related to the kind of writing the learner aspires to; ‘analogue’ corpora that are similar to that kind of writing; and ‘reference’ corpora for genre analysis.

Learners and teachers do not have to be limited to using existing corpora. Doctoral students in a study by Lee and Swales (2006) began working with specialised and general corpora to become familiar with the basic concepts and technology and then compiled corpora of their own writing and of ‘expert writing’ within their field. These personalised corpora focused on the particular discipline interests of students such as pharmacology and educational technology. A learner’s own corpus can be used to compare learner language and ‘expert’ language and ‘learners can gain knowledge of how they can vary their own vocabulary or lexico-grammatical structures, with the concordanced examples providing exemplars’ (Lee and Swales 2006: 68). Having learners compile their own corpora for investigation has the potential to help EAP teachers in particular, as often EAP classes contain a wide variety of first languages studying EAP to prepare for study in many different academic disciplines (Hunter and Coxhead 2007; Coxhead 2008).

Lexical bundles found in corpus studies have found their way into EAP classrooms. Jones and Haywood (2004) explore learning and teaching formulaic phrases found in common between four EAP course books of academic writing, selected on frequency through a corpus search and sorted according to Biber et al.’s (1999) grammatical categorisations of lexical bundles. Despite many efforts in the classroom, the study finds that while the students’ awareness of formulaic sequences had risen, learning and using the phrases in writing did not go well. According to Jones and Haywood, students seemed not to commit the target bundles to memory well, or appeared to focus on already known or salient bundles (2004: 289). Coxhead (2008) points out some difficulties or barriers for teachers and learners in teaching and learning phrases for EAP. One of these barriers was highlighted by a second language learner who commented that it was hard enough to learn one word at a time, let alone two.

In a Swedish study of ‘hands on’ use of corpora into a university-level English grammar course, Vannestål and Lindquist (2007) report,

When it comes to grammar, most students are so used to reading about rules before they see examples that it can take a lot of time and practice for them to understand how they should think when faced with a concordance list of authentic examples, from which they are supposed to extract rules of language usage.

(Vannestål and Lindquist 2007: 344)

Weaker students, in particular, struggled with the corpus work and the researchers and participants conclude that perhaps corpus work might be more suited to writing development and vocabulary than inductive grammar.

The shell noun study mentioned above by Aktas and Cortes (2008) provides useful insights for ESL pedagogy in both academic writing and reading classes. The researchers found that while the ESL writers used shell nouns in their writing, the nouns did not appear in the same lexico-grammatical patterns in both corpora, nor were they used for the same cohesive purposes in the academic written texts. Insights from studies into learner and native speaker corpora have a great deal to offer both pedagogically and in the design of materials (Meunier 2002).

Corpus linguistics has also contributed to the development and sustainability of learner independence (Barlow 2000; Bernardini 2004; Nesselhauf 2004; Starfield 2004; Gabrielatos 2005; Yoon 2008). Lee and Swales (2006: 71) write that corpus-based language instruction is ‘decentring’ and empowering in that the learners themselves can take control of their learning through discovering language use for themselves and referring to texts written by different writers (L1 and L2). The learners became independent of native speakers as reference points for language problems and some reported corpora consultation was superior to reference or grammar books in terms of access and exemplification in related contexts and texts that could be explored across disciplines and from different speakers. Barlow points to the benefits of language students becoming language explorers with corpora when he writes,

One role that the language student can usefully play is that of language researcher (or co-researcher); and like other researchers, the student requires a suitable research environment (tools and data) to facilitate the acquisition of knowledge about a language. By using a corpus and a text analysis program rather than a dictionary, thesaurus, or grammar, the student can learn a language using a rich and adaptable research environment in which the data are selected examples of language use, embedded in their linguistic context.

(Barlow 2000: 106)

Starfield (2004: 154) recounts the experiences of second language PhD students using concordancing as a way for them to begin ‘strategically engaging with the resources of authoritative English’. Concordancing led to ‘growth and development’ in the writing of the postgraduates as well as a growing student empowerment.

Corpora have also been consulted to answer questions teachers in Hong Kong have about language in use (Tsui 2004) with positive results.

Vannestål and Lindquist (2007) comment that working with corpora can be appreciated by some students and not by others. They also find working with corpora to be time-heavy in implementation and that developing independent competent student corpus use can take a great deal of time. It is clear using a corpus needs careful integration with existing curricula and guidance. Studies such as Lee and Swales (2006) and Yoon (2008) allow time for students to become familiar with the tools. Yoon (2008: 45) suggests that one implication of corpus use as an integrated part of an EAP curriculum is that a pedagogy is required that recognises that the acquisition of words and phrases can take longer than traditional or conventional classes tend to allow.

A challenge for EAP and corpus linguistics is to incorporate findings into pedagogy and materials to ensure that all four strands of the language curriculum are involved (see Nation 2007 for a discussion of the four strands). The four strands comprise three meaning-focused strands where communication of meaning is the main focus. These strands are: meaning-focused input, meaning-focused output and fluency. The fourth strand is language-focus. Nation (2007: 9) posits that these four strands should be given equal amounts of time. Concordances and such like clearly fit within the languagefocused strand. Swales (2002) provides examples and personal reflections on how EAP materials and corpus linguistics can integrate several strands. Potentially more such work is being produced in many EAP classrooms, but not many examples of an integrated, four-strand programme of learning appear to exist. For more on L2 teaching and corpus linguistics, see Conrad (2005).

3. How can corpora be used in EAP materials?

Concordances have been a major face of corpus linguistics in EAP materials, beginning with Tribble and Jones (1990) and their Concordances in the Classroom, then on to Thurston and Candlin’s (1997) presentation of rhetorical functions of frequently used words in academic writing through concordancing. Tim Johns (2000) and his data-driven learning (DDL) concept use kibitzer pages (which Johns defines as ‘looking over the shoulder of experts’) to provide opportunities for EAP students to notice features of the target language in their own text and compare them with revised versions. The idea of kibitzers has since been taken up by researchers working on MICASE (see MICASE website) where learners and teachers can investigate corpus data and discussion around aspects of academic language. Such activities can help raise awareness of kinds and features of words and phrases to focus on. MICASE also provides some examples of self-study exercises that can be integrated into an EAP programme to raise awareness of language use in spoken academic contexts and to introduce corpus-based exercises to learners. The set of example materials below asks learners to consider examples of turns out in sample sentences from the MICASE corpus and match them to some possible functions of turns out.

It turns out that the average is the same.

It turns out that the S values are not very reliable.

That turns out to be quite a lot of money.

If your p-value turns out to be so small that you’d reject

- announcing a result in mathematical or statistical computations

- introducing the end or next segment of a story

- used when negating, contrasting, or qualifying – but also emphasizing – an important point

(Simpson et al. 2007)

Textbooks for EAP developed from corpora studies are steadily becoming available. McCarthy and O’Dell’s (2008) Academic Vocabulary in Use was prepared by identifying academic vocabulary in the Cambridge International Corpus of written and spoken English and the CANCODE corpus, as well as checking the Cambridge Learner Corpus for common learner errors. The book introduces concepts such as noun phrases in academic texts, and give us as an instance ‘widespread long term-damage’ (McCarthy and O’Dell 2008: 10). A notable feature of this book is that the first nine units of work are based on concepts of academic vocabulary that learners need to understand, such as exploring what is special about academic vocabulary while presenting target words in context and providing opportunities for practice.

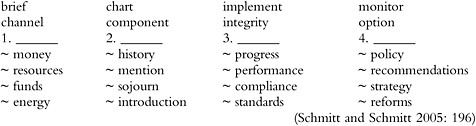

Schmitt and Schmitt’s (2005) book, Focus on Vocabulary: Mastering the Academic Word List, uses the New Longman Corpus to compile collocation exercises that illustrate how words are used in context. In the example below, adapted from the book, we can see a matching activity that requires learners to notice the position of the word in relation to its collocate (the symbol ~ indicates the position of the target word before the collocation).

COLLOCATION

Match each target word in the box with the group of words that regularly occur with it. If the (~) symbol appears before a word in a list, the target word comes before the word in the list. In all other cases, the target word comes after the word in the list.

Teachers might like to actually complete exercises like this themselves so they can become aware of what knowledge of aspects of words needs attention and can think about follow-up activities in the classroom that could be used to further explore these words and their collocates (see Coxhead 2006 for examples of direct learning activities) and incorporate more of Nation’s four strands.

Online sources have become a major source of materials for EAP as we have already seen above, including such sites as the AWL Highlighter by Sandra Haywood at Nottingham University. This website allows teachers and students to input their own texts, or ones supplied by Haywood, and highlight the AWL words up to Sublist 10 in the texts or make gapfills or fill-in-the-blanks activities. See Horst et al. (2005) on an interactive online database and its capacity to expand vocabulary.

Coxhead and Byrd (2007) provide some examples of both computer-based and noncomputer-based techniques for investigating lexico-grammatical patterns in use in EAP. These examples can be used for developing materials for language classrooms and for the preparation of teachers to teach these features of academic writing. An example of the kind of data from corpus linguistics that can be explored in EAP materials in Coxhead and Byrd is the word required, which appears in Sublist 1 of the AWL. Required tends to be used most often in academic writing in its passive form, as in ‘Every company is required to make a statement in writing’ (cited in Coxhead and Byrd 2007: 2), and rarely in the simple past tense. EAP teachers and learners could investigate words such as required using the Compleat Lexical Tutor concordancer online (Cobb n.d.), search for instances of the word in spoken and written corpora and use this data to draw conclusions about how such words are used in academic contexts. The Compleat Lexical Tutor website also has examples of highlighting particular grammatical patterns from corpora that require learners to decide whether the grammatical patterns in a sentence are correct or incorrect. Exercises and tools for making gap fills (or fill-in-the-blanks) based on the AWL are on Haywood’s (n.d.) website called Academic Vocabulary.

Another enormously useful contribution of corpora has been innovations in dictionary making (see Walter, this volume). The ground-breaking Collins COBUILD series (Sinclair 2003 [1987]), working with the Bank of English, pioneered this area of continuing development, with the fourth edition published in 2003. The Longman Exams Dictionary (Mayor 2006) includes examples from reports and essays written in academic contexts. These learner dictionaries have also taken up the concept of defining words for second language learners using a common vocabulary of 2,000 words, drawn from corpus research.

Learner corpora have contributed significantly to dictionary making (Granger 2002; Nesselhauf 2004). A recent example is the inclusion of findings and insights from work by researchers such as Gilquin et al. (2007) in the second edition of the Macmillan Dictionary for Advanced Learners (Rundell 2007). Other examples are the Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English (LDOCE), where learner corpora were consulted to provide advice on how not to use a word in context and the Longman Language Activator, where common learner errors were drawn from the Longman Learner Corpus. An online search of the LDOCE of according to produced the following dictionary entry. Note the advice in the section marked with an exclamation mark (!):

according to S2 W1

1 as shown by something or stated by someone:

• According to the police, his attackers beat him with a blunt instrument.

• There is now widespread support for these proposals, according to a recent public opinion poll.

! Do not say ‘according to me’ or ‘according to my opinion/point of view’. Say in

my opinion In my opinion his first book is much better.

(LODCE Online n.d., www.ldoceonline.com/dictionary/according-to)

4. What can a corpus tell us about EAP learner language?

We have already seen throughout this chapter that learner corpora have had a major impact on EAP, particularly in dictionary making and research into academic writing in context. Granger and her colleagues in Belgium and other researchers have moved corpus studies for EAP into completely new realms of possibilities through their compilations and analyses of learner corpora. Granger makes a strong case for the importance of learner corpora when she writes,

Native corpora provide valuable information on the frequency and use of words, phrases and structures but give no indication whatsoever of the difficulty they present for learners in general or for a specific category of learners. They will therefore always be of limited value and may even lead to ill-judged pedagogical decisions unless they are complemented with the equally rich and pedagogically more relevant type of data provided by learner corpora.

(Granger 2002: 21–2)

Granger provides two key uses of learner corpora in classrooms. First, form-focused instruction whereby learners are encouraged to notice the gap between their output and native output: fossilised learners in particular may benefit from this sort of instruction. The second use of learner corpora is data-driven learning, which we have already touched on above (see Gilquin and Granger, this volume). For an overview of learner corpora, see Granger (2002: 3–36) and Flowerdew (2002).

Learner corpora studies have already shown some particularly useful insights into differences between first and second language writers in EAP. Gilquin et al. (2007) relate an important finding for EAP learners and teachers, which is that learner language appears to indicate that some of its characteristics are limited to one population of L2 speakers, whereas others appear to be shared with many different L2 speaker populations. Learner corpora have the capacity to compare L2 with L1 as well as L2s with other L2s (Gilquin et al. 2007) and learner corpora research has brought to light some interesting findings on the use, misuse and, at times, overuse of particular lexical items. Flowerdew (2001) reviews early work on learner corpora and explores the use of small learner corpora findings on collocations, pragmatic appropriateness and discourse features in the preparation of materials for EAP. She suggests ways in which these findings can be integrated with native corpora. For more on the evidence of learner corpora, see for example Granger et al. (2002) and Hunston (2002). For more on learner corpora in materials design and pedagogy see Flowerdew (2001); Granger et al. (2002); Nesselhauf (2004).

5. What might the future be for corpora in EAP?

An exciting development in future would be to see more research into language in use in the secondary context to support learning and teaching of younger learners in their school-based studies and in preparation for further studies. Resources such as easily accessible online and paper materials, better dictionaries and school materials based on information concerning what these learners need to learn are very much in need (Pat Byrd, personal communication, 29 October 2008). A more co-ordinated research-, pedagogy- and materials-based agenda for EAP at undergraduate and postgraduate level that incorporates both learner and native corpora internationally is also important.

Developing and exploiting multi-media corpora (Ackerley and Coccetta 2007; Baldry 2008) for EAP may be an avenue for the future. A multi-media corpus can help overcome two difficulties with spoken corpora. The first is that spoken text becomes a written text, and the second is that the visual information which is present with speaking such as gestures and facial expressions is not available with written spoken corpora (Ackerley and Coccetta 2007). Multi-media concordancing allows for analysis of learner and native language in its real context (see Adolphs and Knight, this volume), as well as the inclusion of visual information such as tables, charts, maps, and so on, that are often presented in lectures and textbooks. Ackerley and Coccetta (2007) describe tagging of the corpus for language functions which can be searched through phrases such as ‘spelling out a word/expression’ and ‘expressing dislike’. Multi-media corpora might be able to reflect the complexities of oral presentations in a university context where the speaker is using a visual tool such as PowerPoint and a whiteboard and full picture of such a teaching and learning space. They might also help researchers find out more about learners’ interaction and learning from multi-media in their studies (Hunter and Coxhead 2007).

Another potential avenue for the future is parallel corpora for EAP that can be used to examine aspects of language. Some parallel corpora for general purposes already exist, such the ones described in the study of the use of the reflexive in English and in French in Barlow (2000) (see also Kenning in this volume). In the future, perhaps multi-lingual corpora might be developed that can further inform EAP corpus linguistics research. Such corpora may provide insights into how different languages express similar academic concepts in different ways and how frequency of use and collocational restrictions might affect lexical choices, as well as how different subject areas might employ a word differently. Nesselhauf (2004) writes of international corpora where the output of first language speakers of different first languages, and ESL and EFL speakers of the same L1, could be compared to find out more about instructed and natural language acquisition. Gilquin et al. (2007) call for textbooks that use learner corpora to inform learners of typical language learner errors such as overuse or misuse of lexical items. This chapter has looked at some of the ways in which corpora have been developed to inform EAP teachers and learners. This research has not only counted things, as Gawande (2007) encourages professionals to do, but it has broken new ground in corpus linguistics in methodology and analysis. Gradually we have seen that the learner is now at the centre of corpus linguistics for EAP. There is much work yet to be done, particularly in pedagogy and materials design, but this work will be done, and more.

Further reading

Chambers, A. (ed.) (2007) ‘Integrating Corpora in Language Learning and Teaching’, ReCALL 19(3): 249–376. (This special issue contains articles on more general language learning including topics such as computer-based learning of English phraseology and grammar, as well as using a multi-media corpus.)

Sinclair, J. (2004) How to Use Corpora in Language Teaching. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. (This excellent, practical book is part of the Studies in Corpus Linguistics series, edited by E. Tognini Bonelli.)

Teubert, W. and Krishnamurthy, R. (eds) (2007) Corpus Linguistics: Critical Concepts in Linguistics. London: Routledge. (This six-volume set contains a wide range of major articles in corpus linguistics.)

Thomson, P. (2006) ‘Assessing the Contribution of Corpora to EAP Practice’, in Z. Kantaridou, I. Papadopoulou and I. Mahili (eds) Motivation in Learning Language for Specific and Academic Purposes. Macedonia, University of Macedonia [CD Rom], no specific page numbers given, available online. (This article takes an overview of corpora use in EAP including discussion on trends and issues in EAP-related corpora as well as the application of corpus-based findings and methodologies to classroom teaching and its limited uptake in the classroom thus far.)

——(ed.) (2007) ‘Corpus-based EAP Pedagogy,’ Journal of English for Academic Purposes 6(4): 285–374. (This special issue provides an excellent range of articles specifically related to EAP pedagogy and corpus linguistics.)

References

Ackerley, K. and Coccetta, F. (2007) ‘Enriching Language Learning through a Multimedia Corpus’, ReCall 19(3): 351–70.

Aktas, R. and Cortes, V. (2008) ‘Shell Nouns as Cohesive Devices in Published and ESL Student Writing’, Journal of English for Academic Purposes 7: 3–14.

Baldry, A. (2008) ‘What are Concordances for? Getting Multimodal Concordances to Perform Neat Tricks in the University Teaching and Testing Cycle’, in A. Baldry, M. Pavesi, C. Taylor Torsello and C. Taylor (eds) From Didactas to Ecolingua: An Ongoing Research Project on Translation. Trieste: Edizioni Università di Trieste, pp. 35–50; available at http://hdl.handle.net/10077/2847 (accessed 26 March 2009).

Barlow, M. (2000) ‘Parallel Texts in Language Teaching’, in S. Botley, A. McEnery and A. Wilson (eds) Multilingual Corpora in Teaching and Research. Amsterdam: Rodopi, pp. 106–15.

Bernardini, S. (2004) ‘Corpora in the Classroom: An Overview and Some Reflections on Future Developments’, in J. Sinclair (ed.) How to Use Corpora in Language Teaching. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 15–38,

Biber, D. (2006) University Language: A Corpus-based Study of Spoken and Written Registers. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Biber, D., Finegan, E., Johansson, S., Conrad, S. and Leech, G. (1999) Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written English. London: Longman.

Biber, D., Reppen, R., Clark, V. and Walter, J. (2001) ‘Representing Spoken Language in University Settings: The Design and Construction of the Spoken Component of the T2K-SWAL Corpus’,in R. Simpson and J. Swales (eds) Corpus Linguistics in North America. Ann Arbor, MI: Michigan University Press, pp. 48–57.

Biber, D., Conrad, S. and Cortes, V. (2004) ‘If You Look At … : Lexical Bundles in University Teaching and Textbooks’, Applied Linguistics 25: 371–405.

Chen, Q. and Ge, G. (2007) ‘A Corpus-based Lexical Study on Frequency and Distribution of Coxhead’s AWL Word Families in Medical Research Articles (RAs)’, English for Specific Purposes 26: 502–14.

Cobb, T. (n.d.) The Compleat Lexical Tutor. Montreal: University of Montreal; available at www.lextutor.ca/ (accessed 26 March 2009).

Conrad, S. (2004) ‘Corpus Linguistics, Language Variation, and Language Teaching’, in J. Sinclair (ed.) How to Use Corpora in Language Teaching. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 67–85.

——(2005) ‘Corpus Linguistics and L2 Teaching’, in E. Hinkel (ed.) Handbook of Research in Second Language Teaching and Learning. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 393–95.

Coxhead, A. (2000) ‘A New Academic Word List’, TESOL Quarterly 34(2): 213–38.

——(2006) Essentials of Teaching Academic Vocabulary. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

——(2008) ‘Phraseology and English for Academic Purposes: Challenges and opportunities’,inF. Meunier and S. Granger (eds) Phraseology in Foreign Language Learning and Teaching. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 149–62.

Coxhead, A. and Byrd, P. (2007) ‘Preparing Writing Teachers to Teach the Vocabulary and Grammar of Academic Prose’, Journal of Second Language Writing 16, 129–47.

——(forthcoming) The Common Collocations and Recurrent Phrases of the Academic Word List. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Coxhead, A. and Hirsh, D. (2007) ‘A Pilot Science Word List for EAP’, Revue Française de Linguistique Appliquée XII(2): 65–78.

Ellis, N., Simpson-Vlach, R. and Maynard, C. (2008) ‘Formulaic Language in Native and Second Language Speakers: Psycholinguistics, Corpus Linguistics, and TESOL’, TESOL Quarterly 42(3): 375–96.

Flowerdew, L. (2001) ‘The Exploitation of Small Learner Corpora in EAP Materials Design’,in M. Ghadessy, A. Henry and R. Roseberry (eds) Small Corpus Studies and ELT. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 363–79.

——(2002) ‘Corpus-based Analyses in EAP’, in J. Flowerdew (ed.) Academic Discourse. London: Longman, pp. 95–114.

Gabrielatos, C. (2005) ‘Corpora and Language Teaching: Just a Fling or Wedding Bells?’ TESL-EJ 8(4): A-1; available at http://tesl-ej.org/ej32/a1.html (accessed 26 March 2009).

Gawande, A. (2007) Better: A Surgeon’s Notes on Performance. New York: Metropolitan.

Gilquin, G., Granger, S. and Paquot, M. (2007) ‘Learner Corpora: The Missing Link in EAP Pedagogy’, Journal of English for Academic Purposes 6: 319–35.

Granger, S. (2002) ‘A Bird’s-eye View of Learner Corpora Research’, in S. Granger, J. Hung and S. Petch-Tyson (eds) Computer Learner Corpora, Second Language Acquisition and Foreign Language Teaching. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 3–36.

Granger, S., Hung, J. and Petch-Tyson, S. (2002) Computer Learner Corpora, Second Language Acquisition and Foreign Language Teaching. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Horst, M., Cobb, T. and Nicolae, I. (2005) ‘Expanding Academic Vocabulary with an Interactive On-line Database’, Language Learning and Technology 9: 90–110.

Hunston, S. (2002) Corpora in Applied Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hunter, J. and Coxhead, A. (2007) ‘New Technologies in University Lectures and Tutorials: Opportunities and Challenges for EAP Programmes’, TESOLANZ Journal 15: 30–41.

Hyland, K. (1999) ‘Academic Attribution: Citation and the Construction of Disciplinary Knowledge’, Applied Linguistics 20(3): 341–67.

——(2002) ‘Activity and Evaluation: Reporting Practices in Academic Writing’, in J. Flowerdew (ed.) Academic Discourse. London: Longman, pp. 115–30.

——(2008) ‘As Can Be Seen: Lexical Bundles and Disciplinary Variation’, English for Specific Purposes 27: 4–21.

Hyland, K. and Tse, P. (2007) ‘Is There an “Academic Vocabulary”?’ TESOL Quarterly 41(2): 235–53.

Johns, T. (2000) Tim John’s EAP Page, at www.eisu2.bham.ac.uk/johnstf/timeap3.htm (accessed 26 March 2009).

Jones, M. and Haywood, S. (2004) ‘Facilitating the Acquisition of Formulaic Sequences: An Exploratory Study in an EAP Context’, in N. Schmitt (ed.) Formulaic Sequences. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 269–91.

Konstantakis, N. (2007) ‘Creating a Business Word List for Teaching Business English’, Elia 7: 79–102.

Krishnamurthy, R. and Kosem, I. (2007) ‘Issues in Creating a Corpus for EAP Pedagogy and Research’, Journal of English for Academic Purposes 6: 356–73.

Lee, D. and Swales, J. (2006) ‘A Corpus-based EAP Course for NNS Doctoral Students: Moving from Available Specialized Corpora to Self-Compiled Corpora’, English for Specific Purposes 25: 56–75. Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English (2003) Harlow: Pearson Longman.

McCarthy, M. and O’Dell, F. (2008) Academic Vocabulary in Use. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McEnery, T., Xiao, R. and Tono, Y. (2006) Corpus-based Language Studies: An Advanced Resource Book. London: Routledge.

Mauranen, A. (2003) ‘The Corpus of English as Lingua France in Academic Settings’, TESOL Quarterly 37(3): 217–31.

Mayor, M. (2006) Longman Exams Dictionary. London: Longman.

Meunier, F. (2002) ‘The Pedagogical Value of Native and Learner Corpora in EFL Grammar Teaching’, in S. Granger, J. Hung and S. Petch-Tyson (eds) Computer Learner Corpora, Second Language Acquisition and Foreign Language Teaching. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 119–41.

Nation, I. S. P. (2007) ‘The Four Strands’, Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching 1(1): 2–13.

Nelson, M. (n.d.) Mike Nelson’s Business English Lexis Site, available at http://users.utu.fi/micnel/business_english_lexis_site.htm (accessed 25 March 2009).

Nesselhauf, N. (2004) ‘Learner Corpora and their Potential for Language Teaching’ in J. Sinclair (ed.) How to Use Corpora in Language Teaching. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 125–52.

O’Keeffe, A., McCarthy, M. J. and Carter, R. A. (2007) From Corpus to Classroom: Language Use and Language Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Reppen, R. (2004) ‘Academic Language: An Exploration of University Classroom and Textbook Language’, in U. Connor and T. Upton (eds) Discourse in the Professions: Perspectives from Corpus Linguistics. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 65–86.

Rundell, M. (2007) Macmillan Dictionary for Advanced Learners, second edition. Oxford: Macmillan Education.

Schmitt, D. and Schmitt, N. (2005) Focus on Vocabulary: Mastering the Academic Word List. White Plains, NY: Pearson.

Scott, M. (2006) WordSmith Tools 4. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Scott, M. and Tribble, C. (2006) Textual Patterns: Key Words and Corpus Analysis in Language Education. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Simpson, R. and Mendis, P. (2003) Idioms Exercise Sets I and II. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan English Language Institute; available at http://lw.lsa.umich.edu/eli/micase/index.htm (accessed 26 March 2009).

Simpson, R., Briggs, S., Ovens, J. and Swales, J. (2000) The Michigan Corpus of Academic Spoken English. Ann Arbor, MI: The Regents of the University of Michigan.

Simpson, R., Leicher, S. and Chien, Y.-H. (2007) Figuring Out the Meaning or Function of Spoken Academic English Formulas (A); available at http://lw.lsa.umich.edu/eli/micase/ESL/FormulaicExpression/Function1.htm (accessed 26 March 2009).

Sinclair, J. (ed.) (2003 [1987]) Collins COBUILD Advanced Dictionary, fourth edition. Collins: London.

Starfield, S. (2004) ‘“Why Does This Feel Empowering?” Thesis Writing, Concordancing, and the Corporatizing University’, in B. Norton and K. Toohey (eds) Critical Pedagogies and Language Learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 138–56.

Sutarsyah, C., Nation, I. S. P. and Kennedy, G. (1994) ‘How Useful is EAP Vocabulary for ESP? A Corpus-based Case Study’, RELC Journal 25(2): 34–50.

Swales, J. (2002) ‘Integrated and Fragmented Worlds: EAP Materials and Corpus Linguistics’,inJ. Flowerdew (ed.) Academic Discourse. Harlow, Essex: Pearson, pp. 150–64.

Thompson, P. (2006) ‘Assessing the Contribution of Corpora to EAP Practice’, in Z. Kantaridou, I. Papadopoulou and I. Mahili (eds) Motivation in Learning Language for Specific and Academic Purposes. Macedonia: University of Macedonia [CD Rom], no specific page numbers given.

Thompson, P. and Tribble, C. (2001) ‘Looking at Citations: Using Corpora in English for Academic Purposes’, Language Learning and Technology 5(3): 91–105.

Thurston, J. and Candlin, C. (1997) Exploring Academic English: A Workbook for Student Essay Writing. Sydney: National Centre for English Language Teaching and Research.

Tribble, C. (2002) ‘Corpora and corpus analysis: new windows on academic writing,’ in J. Flowerdew (ed) Academic Discourse. Harlow, Essex: Pearson, pp. 131–49.

Tribble, C. and Jones, G. (1990) Concordances in the Classroom. London: Longman.

Tsui, A. (2004) ‘What Teachers have always Wanted to Know and how Corpora Can Help’,inJ. Sinclair (ed.) How to Use Corpora in Language Teaching. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 39–61.

Vannestål, M. and Lindquist, H. (2007) ‘Learning English Grammar with a Corpus: Experimenting with Concordancing in a University Grammar Course’, ReCALL 19(3): 329–50.

West, M. (1953) A General Service List of English Words. London: Longman, Green.

Yoon, H. (2008) ‘More than a Linguistic Reference: The Influence of Corpus Technology on L2 Academic Writing’, Language Learning and Technology 12(2): 31–48.

Yoon, H. and Hirvela, A. (2004) ‘ESL Student Attitudes toward Corpus Use in L2 Writing’, Journal of Second Language Writing 13(4): 257–83.