CHAPTER 21

POWER PLAYS

One morning, in a small temple town, Muktananda woke me up at 4 a.m. It was just him. He led me down an alley, then up a long flight of stairs. We entered a small room above a temple, where he had me sit on the floor across from him. He gave me a mantra, which I went on repeating. Afterward, I must have fallen asleep. When I woke up, I was alone. It was about 9 a.m.

Someone came from the group and said, “Baba wants to see you.” I followed the messenger to Muktananda, who was sitting in a big room with other people. He motioned me over.

“What was that mantra about?” I asked.

“It will give you great wealth and powers.”

“Unless it gives me compassion,” I replied, “I don’t want power. I don’t want power without compassion.”

Muktananda looked at me disdainfully and walked away. That moment illuminated the contrast between Maharaj-ji’s path of the heart and Muktananda’s predilection for power and wealth. Of course, both those qualities resonated in me, which was why I was attracted to Muktananda in the first place. I realized at that moment that my focus had shifted, from my head to my heart.

Later in the trip, Muktananda sent me to the ashram of Sathya Sai Baba, at Whitefield near Bangalore. He wanted me to arrange a meeting with Sai Baba, who was a well-known guru with many followers. Muktananda thought Sai Baba was a fake.

When I got to the ashram, I stood in the men’s line for an audience. “Ah, Ram Dass!” said Sai Baba when he saw me. He took me to a small room, where he materialized a medal out of thin air and gave it to me. It was a silver coin with a gold-colored rim. I was impressed, although it didn’t look like real gold. When I left the darshan hall, I showed it to an old sadhu outside. “That’s not a siddhi,” he said. “He has a ghost who transfers these things from a warehouse.” Maharaj-ji subsequently said something similar about Sai Baba, “He brings Dharma [Truth] down to the level of magic.”

This was all spiritual politics. And I was in the middle. The next day, when our group arrived at the ashram, devotees were lined up on both sides of a driveway where Sai Baba was greeting people. Muktananda had his driver go straight up the middle of the driveway. When Sai Baba ignored the car, Muktananda got out and grabbed Sai Baba from behind in a kind of bear hug, supposedly to suppress his powers. (Later, Muktananda told me that Sai Baba had no power.) Then Muktananda got back in the car.

Sai Baba went inside, and a devotee told us we could wait in the darshan hall. There was a throne at one end and a stack of folding chairs at the other. Muktananda got himself a folding chair and sat down to wait. Sai Baba didn’t show for a long while. I went to his devotee and said, “You better get your man here.” He said, “He’s giving an interview for the newspaper.” I said, “You can’t let Muktananda wait.” Leaving Muktananda cooling his heels was not what I’d arranged.

Their meeting was a kind of interguru Olympics of yogic powers, a clash between two spiritual lineages. Muktananda was a Shaivite from the line of Nityananda, a great avadhoot, beyond everything. Sai Baba was said to be an incarnation of an earlier saint, Shirdi Sai Baba. When Sai Baba entered the room, the two met in the middle. Muktananda recited to him the story of Narcissus, the Greek myth about the supremely vain character who looks into a pool to admire his own beauty. I felt like I was with two adolescents. I was disappointed in both of them.

The yatra concluded with our return to Ganeshpuri. Though we settled easily into the ashram routine, those of us who knew Maharaj-ji wanted to get back to him. Ramesh flew to New Delhi, then went directly up to the hills to do a retreat at the kuti in K. K.’s family orchard, where several saints had stayed.

I went to meditate in some caves at Surat that I had heard about, where you just sit and they bring you food and water. Like a meditation hotel. It was very hot, and I took off my clothes. There was a comfortable swinging chair in my cell, like a hammock chair. The food was good.

When I meditated, the mantra Muktananda gave me for wealth and power kept coming into my mind. I was still attracted to power. I wasn’t going deeply into the mantra, though. I was just using it to examine my attachments to power and wealth. I could see how really using it would increase my affinity for them.

I didn’t see Muktananda again for several years, back in the US. He was on another world tour by then and still sore that I’d rejected the opportunity to be his heir. When he died, his legacy was marred by the machinations of his devotees. Given his history of power games, it was ironic and maybe fitting. When I told Maharaj-ji about Muktananda’s private dining room with gold plates and his pearl-blue Mercedes, he said simply, “He holds on too much.” That was long before rumors of Swiss bank accounts and allegations of sexual misconduct.

I think Maharaj-ji put me with Muktananda to work through my desire for power. I fantasized about inheriting his scene, but Maharaj-ji was just running me through my power trips. The balloon of my ego would inflate, then Maharaj-ji would let the air out, sometimes gently, sometimes just, Pop! Once, an old lady came by and took out three paisa, or pennies, she had tied up in her sari. She offered them to Maharaj-ji. He pointed at me and said, “No, give it to him. He needs it.”

Maharaj-ji kept giving me these experiences with power until I saw it was love, not power, that matters.

In Allahabad Maharaj-ji said to meet him at his ashram in Vrindavan, an ancient temple town near Agra, in northern India. Vrindavan is where the god Krishna spent his childhood, and it is a center of Krishna devotion. Danny Goleman, Jody (Dwarka) Bonner, and Krishna Das picked me up in our VW van, and together we drove the twenty or so hours.

When we got to Vrindavan, Krishna Das, whom Maharaj-ji also called “Driver,” missed the turn to the ashram, and we had to go the slow way through the bazaar. When we got to the ashram, there was no sign of Maharaj-ji. The priest said he was probably up in the mountains.

Crestfallen, we got back in the van to leave. Just as Krishna Das was putting the key in the ignition, a small Fiat sedan pulled up and skidded to a halt in a cloud of dust and gravel. Maharaj-ji got out with Gurudatt Sharma, a longtime devotee from Kanpur. Without even glancing at us, Maharaj-ji strode into the ashram. No greeting, no word of acknowledgment, nothing. We sat there stunned.

Years later, Gurudatt told us that Maharaj-ji awakened them at two in the morning and said he had to get to Vrindavan right away. As they approached Vrindavan, Maharaj-ji abruptly told the driver to stop. They waited for ten minutes, a pause that coincided with our detour through the bazaar, perfectly timing his arrival to our moment of greatest despair.

We followed Maharaj-ji into the ashram, and he asked us about Muktananda. I told him about the yatra, and before I could mention my visit to Surat, he said to me, “It’s good to meditate without clothes.” I’d thought I was alone in that cave. Apparently not.

Unbeknownst to Danny and Krishna Das, on the long drive from Surat, I’d made out with Dwarka in the back of the van while the other two drove or slept. Dwarka and I had been lovers when we had privacy during the whole yatra. Now that we were sitting in Maharaj-ji’s office, he pointed at Dwarka. “You gave him your best teachings,” he told me.

No one else got the joke besides me and Dwarka. Maharaj-ji had a hilarious sense of humor, but understood only by those he intended it for. I’d been feeling guilty about fooling around, but the lightness with which he treated my lust freed me from taking myself so seriously. He was saying, “You want to keep getting lost in that? Okay, but don’t get lost in shame and guilt too. It’s just a desire.” He saw everything. Those hidden feelings weren’t hidden from him.

Maharaj-ji’s teaching was intimate, funny, straight to the heart, and not heavy-handed, though he could be very fierce too. I associate that cosmic humor with the feeling of his grace. Being able to laugh at oneself is grace.

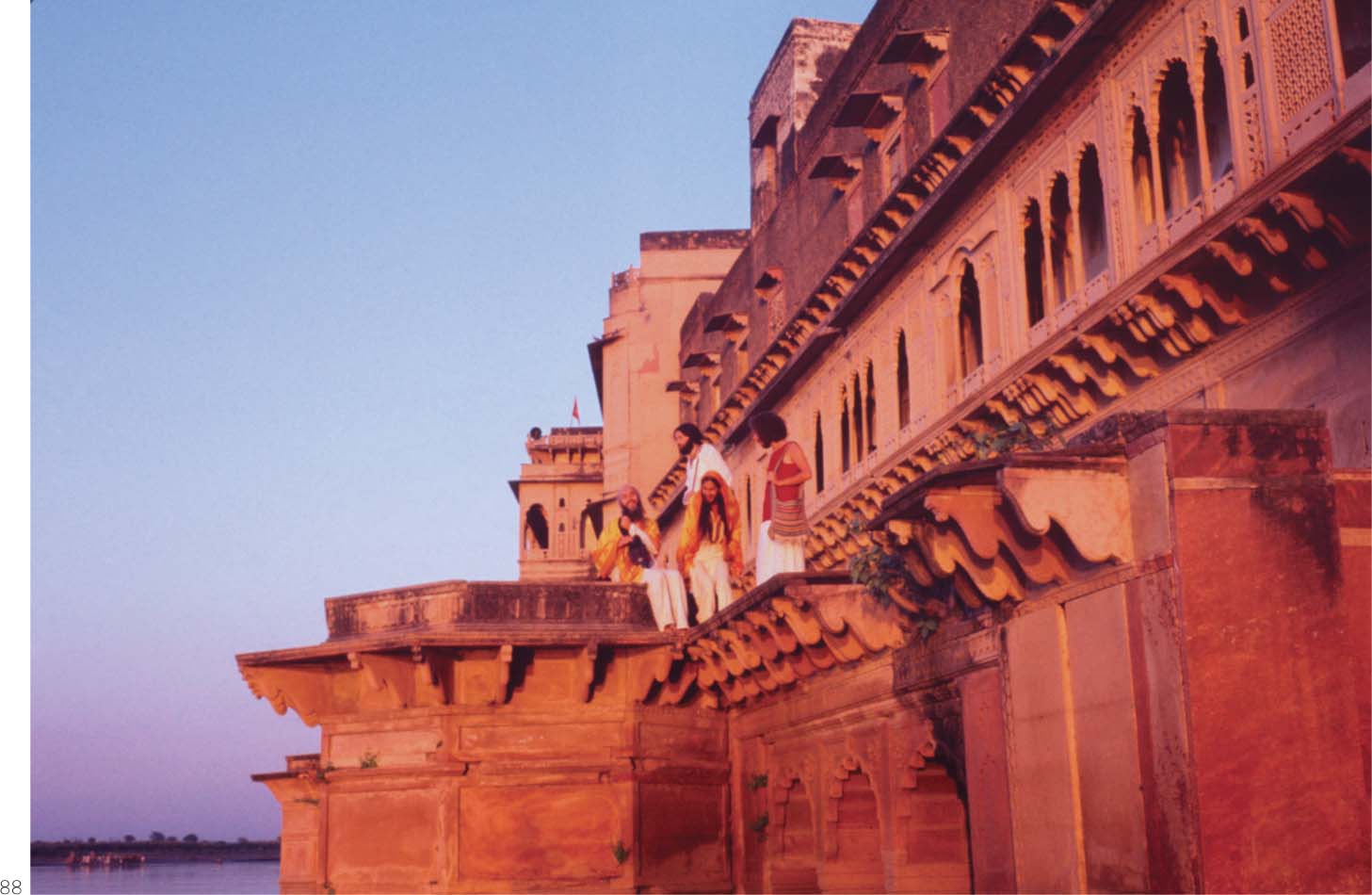

Sitting with Maharaj-ji in the temple courtyard one beautiful evening, Maharaj-ji asked me a question. It was near dusk in Vrindavan, where Krishna performs his love dance with ten thousand cowherd girls, the gopis. Indians refer to this time of day as “cow dust” with romantic precision.

“Did you give me some medicine last time you were in India?”

“Yes, Maharaj-ji.”

“Did I take it?”

“I think so.”

“Do you have any more?”

My doubts about whether Maharaj-ji had consumed the LSD I’d given him on my first trip to India had carved a well-worn rut in my mind. In the US, I’d reverted to my psychologist role, thinking of him as a subject in an experiment. It was my rational mind trying to explain what I’d seen. There was also a vestige of my cynical professorial self that didn’t believe. Once back in India, though, my concerns seemed unimportant. In his presence, my doubts receded until he reminded me.

I went to my room and got my medicine bag. I had five White Lightning LSD pills, but one was broken. He took the four whole ones out of my hand, one at a time. Then, one at a time, so I could see, he carefully placed them in his mouth, making an ahhh sound, as if he really enjoyed them. He was hamming it up for dramatic effect.

He asked for water and said, “Will it make me insane?”

“Probably,” I said.

He pulled the blanket up over his head and, after disappearing for a minute, peeked out. His eyes were rolling around in his head and his tongue was hanging out the side of his mouth. His face had an expression of shock. He looked completely psychotic.

“Oh, God, what have I done?” I thought in a panic. I had gauged his weight, but I didn’t know his age, and there was no telling what such a heavy dose would do to him this time. “He was such a sweet old man!”

Maharaj-ji laughed delightedly. It was a total put-on. He stopped playacting and said, “Got anything stronger?” He was beaming. He was just playing with my mind, like a kid with a toy. He went back to talking with people, completely ordinary conversations, at least for Maharaj-ji. I was watching like a hawk. Nothing happened. Nothing at all.

So Maharaj-ji delivered the coup de grace to my doubts. Not only did he validate the first experience; he again showed he could read my mind, with all my uncertainty. I’d known inside that I had come to the end of my psychedelic path. He confirmed that assessment. Actually, he rubbed my nose in it thoroughly.

Chagrined, I began to see the humor in the whole thing. In both LSD incidents, Maharaj-ji was laughing at my Western reliance on externals and stretching my conception of his consciousness. I had thought of psychedelics as a spiritual path, and now he was pulling that conceptual rug out from under me. From the place of oneness where Maharaj-ji sits, psychedelics are just a fragmentary shard of a vastly deeper reality. He showed me they are a limited window, all the while reflecting back to me the deeper place of love within myself.

The question arose repeatedly with other westerners. Many had reached Maharaj-ji thanks to life-changing experiences with psychedelics. They wanted to know if they were real. “These medicines were known in the Kulu Valley long ago,” he said, “but yogis have forgotten about them.” He said psychedelics could be useful if you took them in a quiet, cold place and your soul was turned toward God. “They allow you to come into the presence of Christ, to have darshan, but you can only stay for two hours.”

It was good to visit Christ, Maharaj-ji said, but it was better to be Christ. “This medicine won’t do that,” he continued. “It’s not the true samadhi, absorption in God. Love is a much stronger medicine.”

That statement lowered the curtain on my psychedelic life. After my first encounter with Maharaj-ji, I continued to talk about psychedelics in a positive way; I was still grateful for them, but now they became less important. I focused on stabilizing my experiences through yoga and meditation. Oh, I continued to take trips now and again. But drugs were no longer a mainstay in my spiritual toolbox. As Alan Watts said, I got the message and I was hanging up the phone. I was becoming comfortable in my own awareness, my true being.

I always honor what psychedelics have done for me. They are an entry point, a path through colorful astral planes and exquisite experiences. I touched my soul on psilocybin. The problem is, you have to come down. Now when I hear about people tripping, I think of it as letting children play. Let them enjoy the colors and patterns and sounds. I am being pulled more deeply into my heart, into the witness, into the One with Maharaj-ji. He is the gravitational pull of the sun in the heart, Ram.

I kept in contact with Anagarika Munindra, the Vipassana teacher from Bodh Gaya who hosted Goenka. When I learned he spent summers in the Himalayas, meditating in the village of Kausani, I asked to join him. I felt pulled to deepen my meditation practice. Munindra agreed to lead a retreat for a few of us during the monsoon. I arranged for housing near a school called the Lakshmi Ashram and paid to have a new cistern installed, so we’d have water. When I told Maharaj-ji of our plans, he said,“As you like.” Not exactly an enthusiastic endorsement.

There were five of us, ensconsed in our retreat house, when Munindra pulled out. His mother was ill, and he couldn’t come. Monsoon season in Kausani was filled with leeches and rain, rain, rain. Once in a great while, the Himalayas peeked out to remind us of the towering peaks shrouded by the clouds.

From our hill aerie we could see the bus stop at the bottom of the hill. One day, we noticed some westerners get off the bus. They trudged up the hill to the house. Maharaj-ji had sent them to our retreat. The next day, a few more came, and the day after, even more. Every day, more people arrived on the bus. Maharaj-ji told them to study meditation with Ram Dass.

I had planned to be a humble student for the summer and become an ace meditator. But Maharaj-ji set me up. Now I was the de facto teacher. Remember the old saying? “Those who can, do. Those who can’t, teach.” My meditation vacation was short-lived. Teaching was how I was really going to learn. There was no escaping Maharaj-ji.

There were now about twenty of us, so we moved to a larger space at the Gandhi Ashram, on the ridge below. Gandhi was once interned there by the British Raj, to remove him from the political scene. It didn’t work any better than my retreat plan. Maharaj-ji’s pressure cooker had not been turned down, just moved to a different burner on the stove.

We practiced a mixture of bhakti devotion and meditation. We’d start the morning chanting Ram’s name or singing kirtan, then we’d meditate. The program emerged from who we were. We all knew we’d been put there by Maharaj-ji to work on ourselves—or, rather, for him to work on us together.

As I quieted down, Maharaj-ji was a constant presence. My recent teaching experiences—at Wesleyan, Bucks County Seminar House, the Sculpture Studio, Lama Foundation—had all seemingly come about through my initiative. Kausani was all Maharaj-ji’s doing. It had that flavor of everything coming together perfectly, the availability of the Gandhi Ashram, the monsoon weather. It was too wet to be outside.

My role as teacher included guidance counselor and therapist: my old roles with new tricks. All the training I had in psychology, psychedelics, and spiritual practices was called upon. When I sat with people individually, we would look into each other’s eyes, going deeper and deeper through layers of personality into our souls. I would say, “If there’s anything you feel you can’t tell me, tell me.” Deep feelings, spiritual aspirations, and decades of neuroses bubbled up. Maharaj-ji’s compassionate presence allowed a lot of internal work to be done.

It was intimate, it was truthful, it was sometimes painful and sometimes beautiful. We all made great effort to go within. I was helping the participants witness their psychological games. We were dismantling the ego, thought by thought. Spiritually, we saw ourselves as sadhaks, seekers on the path, instead of in interpersonal relationships. When I sat with someone, we would start with those interpersonal and personality layers, spiritual and psychological stuff mixed together. After a while, we’d get into this place where we were just hanging out together as spiritual friends, witnessing the mind river flowing by.

The teacher role fanned my ego, except that Maharaj-ji kept undercutting it. For example, the most intimate conversations from our one-on-one sessions were overheard from the room above mine through a hole in the ceiling. Intimate confessions strangely became common knowledge.

I was contending with monstrous egos, and not just my own. Maharaj-ji attracted strong personalities, smart and neurotic individuals, some borderline psychotic. Just to get to India in those days, you had to have an incredibly strong drive and sense of purpose and in normative terms be beyond the pale. Picture this crew of characters cooped up together in this tiny Himalayan village for a month in the pouring rain with nothing to do but meditate. It was like a Thomas Mann novel. We would call it The Last Resort. Maharaj-ji had sent them all to my doorstep to study with me. An exquisite structure for ego deconstruction, including mine!

The incessant rains made everyone stir crazy. Other forms of exploration surfaced besides devotion and meditation. Ed Randel, a psychedelic artist who Maharaj-ji named Harinam Das, had some PCP mailed to him from the US. PCP is an anesthetic that is used as an animal tranquilizer and also has mind-altering effects. Old patterns die hard. The risk-taking psychedelic explorer still lived in me, and I decided to take PCP with Ed. I got very high and partially paralyzed from the anesthetic side effects. It took me a while to come down and reintegrate. I was still attached to ecstatic experience, to my greed for bliss.

Over that month of July 1971 that we spent together at Kausani, a feeling of warmth and unity emerged, despite the gossip and backbiting and our being cooped up. The pervasive feeling was love, a foundation that cemented our ties to one another. When we finally got permission to return to Kainchi, we were eager to get to Maharaj-ji. He gleefully teased me, “Ram Dass’s meditation teacher didn’t come. Ram Dass is the teacher!”

We reinstalled ourselves in the Hotel Evelyn in Nainital. As often as Maharaj-ji allowed, we went to Kainchi. We loaded into the VW van, some of us, including me, perched on the rooftop luggage rack. After a couple of weeks as our trusty chariot straining up the Himalayan hills, the chronically overloaded and underpowered VW engine broke down.

We tried to get it repaired in Haldwani, a nearby town at the foot of the hills, but the mechanic there had never seen an air-cooled rear-engine VW. He got nowhere. Maharaj-ji kept repeating, “Take it to Delhi, take it to Delhi!” Finally, we hired a flatbed truck to transport it and found a mechanic in Ghaziabad, on the outskirts of Delhi, who knew foreign cars. He opened the engine compartment, listened, and with a flick of his hand fixed the engine right away. The van ran fine for a while after that.

When we were with Maharaj-ji, time and space didn’t exist. His presence seemed vast and eternal. He would say things about the future that we couldn’t understand. At times you couldn’t tell whether he was talking about the past, the present, or the future. He used to quote the fifteenth-century poet-saint Kabir as if he knew him. Other times, Maharaj-ji would give one of his close devotees, like Gurudatt Sharma or the schoolmaster K. C. Tewari, a whack on the head, and they would go into samadhi. Gurudatt or K. C. would be gone, his body would turn stiff, he’d stop breathing. On one of those occasions, Maharaj-ji said, “I can do that to him because we’ve been together for many births.”

Kabir, Lincoln, Christ—Maharaj-ji spoke of them as if they were present for him. It’s as if Maharaj-ji’s eternal present intersects our timeline at a perpendicular from another dimension. Like the story of two-dimensional Flatland seen from our three dimensions, Maharaj-ji sees time from outside our reality. When he spoke of Christ, tears rolled down his face. It was as if he was witnessing the crucifixion. Later he told us to meditate the way Christ meditated. When asked how Christ meditated, he said, “He lost himself in love.”

After hearing Maharaj-ji talk about Christ, reading the Bible became an oracular experience. To our new ears, it grew into a living book, which is what the Bible is actually supposed to be. If the weather was fair, we sat on the veranda of the Hotel Evelyn and read from important spiritual texts. On Sundays, I’d read from the Gospel of John or other parts of the New Testament. I hearkened back to early Quaker meetings with my friends, the McClellands. Several of us wore crosses around our necks. On Tuesdays, we’d read the Ramayana chapters about Hanuman, the monkey god. Maharaj-ji likened Christ and Hanuman through their selfless service to God.

K. K. Sah came to the hotel to teach us the arti ritual, the “waving of the lights,” an offering to the guru, to God. It took us a while to learn the Hindi. In great triumph, we were brought forth from the back of the ashram to perform for Maharaj-ji and the Indian devotees. I’m not sure whether he was showing us off or having a good time at our expense. It was probably some of both. Everyone enjoyed it. We didn’t care as long as we got to hang out more with Maharaj-ji.

At Kainchi, they gave out small booklets with a picture of a flying monkey. Krishna Das asked what it was. That was our introduction to the Hanuman Chalisa, forty Hindi verses in praise of Hanuman by the sixteenth-century saint and poet Tulsidas. At first, we massacred the Hindi pronunciation, but gradually many of us memorized it.

The tradition is to sing it 108 times in a day. Each recitation takes ten to fifteen minutes, which means most of a day. Thanks to Krishna Das, who has recorded it many times, these days you can hear the chalisa online or on satellite radio wherever you are. I thought it would be too hard to learn in the West, but it’s amazing how it has gained a foothold. Many people learn the chalisa as their main spiritual practice.

Dada Mukerjee often served as our translator, which we loved because he and Maharaj-ji had a very playful relationship. Dada was always blissed out when he was with Maharaj-ji. Being with the two of them was ecstatic and often funny. Because Dada was an economics professor, his English was perfect. He was sometimes embarrassed about translating Maharaj-ji’s colorful language. We delighted in their interaction. Dada would give assent to anything Maharaj-ji said: “Hahn, Baba, hahn, Baba. Tikh hai, Baba.” (Yes, Baba, yes, Baba. Okay, Baba.)

Witnessing Dada at Kainchi was seeing someone in heaven. There was a streak of deep compassion in his nature. He and his wife had no children, although his wife, whom we called Didi (sister), was the headmistress of a school. They took great care of animals, feeding their leftovers to neighborhood dogs and cows. At Kainchi, the otherwise fierce temple watchdogs cried and moaned when Dada left. Maharaj-ji was ever affectionate and tolerant of Dada’s habits. Dada had a dispensation to take smoking breaks, even though smoking around a holy man was considered disrespectful. Maharaj-ji would hold up two fingers and pantomime smoking, motioning Dada to go around the corner. When Maharaj-ji died, Dada stopped smoking.

Dada told us that one time he and Maharaj-ji were sitting quietly. Dada looked over, and in place of Maharaj-ji, he saw a large golden monkey, Hanuman. Another time, Maharaj-ji took Dada’s hand at Kainchi, and they walked off together. They disappeared from view. Maharaj-ji returned, but Dada was nowhere to be found. Other devotees grew concerned and searched for him. Dada was found up the road, wandering in a daze. He was flushed and in an ecstatic state. He had no recollection of what had happened.

My mother always fed everybody who came to our house. Maharaj-ji did the same at his temples. When we asked Maharaj-ji how to raise kundalini, the spiritual energy, he said simply, “Feed everyone and love everyone. Remember God.”

Food was a way Maharaj-ji distributed blessings. The Hindu custom is that once a high being touches the food or it is offered to a deity it takes on that vibration and is blessed food, or prasad. Devotees brought bags and baskets of fruit and sweets to the ashram. Maharaj-ji would distribute his blessings with dead aim. Someone would be deep in meditation in the back row and be startled by a sudden apple or banana going thump! in the middle of their chest (or occasionally in the testicles).

Maharaj-ji was said to have Annapurna siddhi, the power of the goddess of abundance. When he was around, there were always heaps of pooris and potato subji beautifully prepared in vast quantities. Besides potatoes, the diet consisted of wheat, butter, and sugar—basically carbs and fat. By conventional standards, not healthy—but prasad is metaphysical food. Prasad transmits blessings. If you can receive it as such, it’s holy communion. Satsang members who got hepatitis and were forbidden by the doctor from eating anything with oil or spice ate deep-fried pooris and spicy potatoes at the ashram and recovered.

Maharaj-ji saw that we hungered, and not just for food. One time, Krishna Das was visiting Kainchi with a wedding party from his adoptive Indian family, the Tewaris. He was overwhelmed to see the affection between all the cousins of the various generations. It was so different from what he’d experienced growing up on Long Island. He asked Siddhi Ma, the Mother of the ashram, about it, and she said, “This love is what you missed growing up. When you were a child, love was used to control you.” That was true for me too.

K. K. says that love in traditional Indian families is the foundation of bhakti, or devotion. In their multigenerational households, grandmothers often perform daily puja, or worship, and they pass that love for God on to the little ones. Kids grow up in that devotional atmosphere, sharing love with siblings and cousins in the close proximity of extended family.

Ideally, an Indian family is also satsang, spiritual family. The first time I was in India, I experienced that devotional bond with K. K., his relatives, and other Indian devotees. Now I was back, this time with a gaggle of westerners. This circle became the core of a Western satsang. Living with satsang changed my kindred identification from my blood family to my spiritual family. Satsang is loving and supportive, and it doesn’t have so much of the element of power that had consumed my birth family.

This is not to say our satsang was one big, lovey-dovey, happy hippie family. The westerners around Maharaj-ji sometimes competed for his attention, which we facetiously called the Grace Race. Everyone was going through intense personal transformations. Kainchi was a pressure cooker.

The Hotel Evelyn became part ashram, part hangout, and part therapy office. We came to call our main practices the “five-limbed yoga”: eating, sleeping, drinking tea, gossiping, and walking about. Even though I’d given few clues to Maharaj-ji’s whereabouts, I was now surrounded by westerners, many of whom I’d inspired to come.

It was different from being a solo yogi in the Himalayas. Like everyone else, I had karmic stuff to work through: anger, lust, power. Maharaj-ji confronted me with my attachments, sometimes with gentle humor and sometimes with situations from which I had no escape. He gave me the title commander in chief of the westerners, then promptly undermined my authority and attempts at order at every turn.

Meanwhile, we were joined by new devotees, like Elaine and Larry Brilliant. After Wavy Gravy and the Hog Farmers left India, Elaine had stayed on to attend one of Goenka’s Vipassana courses. She met Mirabai Bush, who encouraged her to join us at Kainchi. She was quickly absorbed into Maharaj-ji’s love field. He named her Girija, “mountain daughter,” after the consort of Shiva.

Girija wrote to her husband, Larry, asking him to come back to India to see Maharaj-ji. When Larry, who was a trained doctor, finally came, Maharaj-ji told him that he would work for the United Nations and help eradicate smallpox. As a hippie doctor Larry had no experience in public health. He couldn’t imagine how Maharaj-ji’s prediction would be fulfilled.

Remarkably, Larry eventually became second in command of the World Health Organization’s smallpox eradication program in India and Bangladesh, where the last cases on earth were seen. Maharaj-ji said, “This is God’s gift to humanity, because of the dedicated health workers. God will help lift the burden of this terrible disease from humanity.” It was one of the only times in history that a major disease has been wiped from the Earth.

Although the Indian devotees were enormously welcoming and tolerant of us crazy videshis (foreigners), we missed some colorful details by not speaking the language. One day a woman who had rented a cowshed from a farmer in the valley reported her place had been broken into and some of her things stolen. An intense and rapid exchange ensued between Maharaj-ji and the young interpreter, which was translated as, “Maharaj-ji says you should lock your door.”

Later that day, after lunch, the westerners were sitting around when the translator, Ravi, a young Indian guy, came by, laughing to himself. He said, “What Maharaj-ji really said was, ‘These stupid sisterfuckers don’t even know enough to lock their doors! What do they expect?’”

I was watching Maharaj-ji from my old room at Kainchi, on the second floor. I was kind of spying on him. Earlier that morning, he’d again told us to love everybody. I saw Maharaj-ji call up one of the Indian devotees who worked at the temple and start berating the guy, who cowered in front of him.

I was shocked. Now I thought Maharaj-ji was a hypocrite, that he would tell us to love everybody, and there he was, tearing into this fellow. He was a fraud. And I had brought all these westerners to see him. I felt betrayed.

Dada Mukerjee came to find me. Maharaj-ji told him, “Ram Dass saw me get angry” and sent him to talk to me. Dada explained that Sharma, the helper, had let a whole storage room of potatoes rot. Food that could have fed a lot of people had been wasted through his negligence. Still, I couldn’t face Maharaj-ji. Sharma came by, asking for people to intercede for him with Maharaj-ji. I walked out to the bus with him.

When I came back into the temple at the front gate, Maharaj-ji was standing up near the tukhat. I felt like I had to confront him about telling everyone not to get angry while he was blowing his top at this guy for letting a few potatoes spoil.

What I had missed was that Maharaj-ji had not said, “Don’t get angry.” He’d said, “Love everybody.” Although Maharaj-ji had apparently lost it with Sharma, he hadn’t been attached to the anger. It had been necessary. Dada had already tried to tell me this. “Maharaj-ji loves Sharma,” he said.

Later that day, at our afternoon darshan, Maharaj-ji spoke to a couple who were having relationship issues. I’d been counseling them about anger in their relationship. He said to them, “No matter what someone else does to you, never put anyone out of your heart.”

It was a teaching I needed. I was frustrated with all the other westerners hanging around Maharaj-ji, and anger toward my satsang sisters and brothers was building up. I’d hoped my time in India would renew and replenish me after all the teaching I had done in the US. But every time I tried to be alone, Maharaj-ji sent me more students. Over the year I’d been in India, I’d had exactly eleven days when I was not surrounded by westerners.

At the hotel, I’d been meeting with couples and individuals to help them iron out their relationship issues. There were a number of westerners who arrived at Kainchi as friends or casual lovers, and when they came to Maharaj-ji, he declared them married.

These couples had no particular idea what this spiritual marriage meant. I was left to help pick up the pieces and sort out the mysteries of their relations. They would come to my room for advice. It was both spiritual counsel and talk therapy.

I felt like none of the westerners had any understanding of dharma. I was mad and feeling very righteous about it. So I put a note on my door that read, Do Not Enter. For two weeks, I refused to see anyone. The others told Maharaj-ji. When I saw him, he said, “Won’t you help them?”

I was supposed to be a devotee of Hanuman, who loves and serves everyone as God. Hanuman wouldn’t have a Keep Out sign. But I was struggling. One day, when we were all supposed to take the bus to Kainchi, I arrived at the bus stop a couple of minutes late, only to find that the satsang had left me behind. “They don’t even care!” I fumed.

Maharaj-ji had said, “A saint should not touch money,” so I’d stopped carrying it, relying on an easygoing Canadian who agreed to be my bag man and pay for daily expenses like bus fare. Now I was so angry I couldn’t talk to him.

I decided to walk the seven or eight kilometers to Kainchi, over the hills, through the forest and the tiny farm villages that dotted the countryside. It is a beautiful and idyllic walk, and although it soothed me, I was tired by the time I got to the ashram. When I entered, another Canadian intercepted me to offer a leaf plate of prasad, because they were already in the middle of lunch. He was being perfectly nice and accommodating. But as he handed me the pooris and potatoes, a wave of anger broke over me. I took the food and shoved it in his face.

“Ram Dass!” Maharaj-ji yelled across the courtyard. Throwing prasad was definitely a sacrilege. “What’s the matter?”

I ran over to him. The other westerners sat on the opposite side of the courtyard, looking stunned. I said, “I’m angry at those people. They’re all adharmic, bad people.” I looked over and saw them all in their badness. They were whiny, selfish, needy.

I also knew I was responsible for most of them being there. I hated myself for that too. By then I was crying. “I hate everybody, including myself,” I blurted out. “I hate everybody but you.”

Maharaj-ji sounded sympathetic. “Oh, Ram Dass is angry,” he said. Then he looked at me. “Ram Dass, love everyone. Love everyone and tell the truth.”

I said, “Maharaj-ji, the truth is: I am angry.”

He leaned over and looked me in the eye, practically nose to nose. He said, “Tell the truth. And love everyone.”

I knew in that moment I had to choose whether to hold on to my righteous anger or surrender to Maharaj-ji. It’s a rare moment when your guru gives you a direct command. Not to be taken lightly.

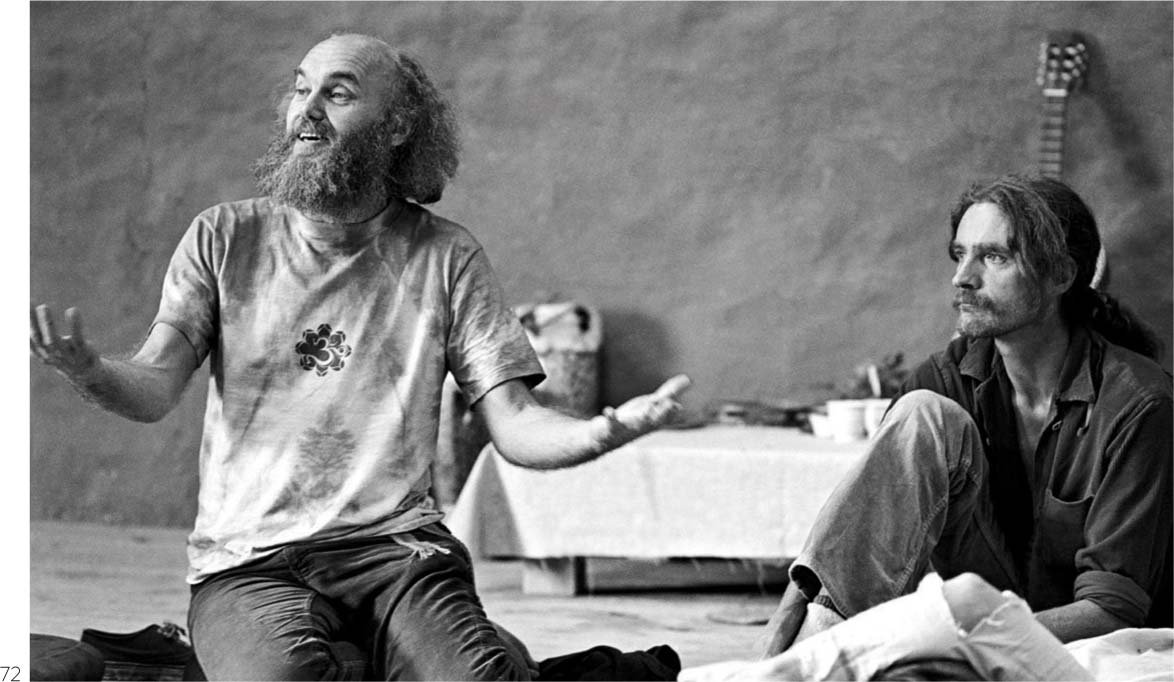

With Steve Durkee, Lama Foundation, circa 1974

Meditating in the dome at Lama

Tellis Goodmorning, a Native American mentor for the Lama Foundation

Little Joe Gomez, an elder in the Native American Church, Lama Foundation

The Blue Bus, still used as a residence at the Lama Foundation

With Papa Trivedi at Ganeshpuri, 1971

Swami Muktananda, London, 1970

Hilda Charlton, New York, early 1970s

Bhagwan Nityananda, Muktananda’s guru

Muktananda holding Satya Sai Baba at their meeting in Whitefield, near Bangalore

“Nainital High,” class of 1971

Meditating with Maharaj-ji after his instruction to “Love everyone and tell the truth.”

The venerable VW van, en route from Nainital to Kainchi

Coming down from PCP, Kausani, 1971

Anandamayi Ma at her ashram near Haridwar

Maharaj-ji with Dada Mukerjee, Kainchi, 1971

Along the Yamuna River in Vrindavan

Bhagavan Das and Hari Dass, Haridwar, 1970

In Kainchi, 1971

Maharaj-ji with the first printing of Be Here Now

With Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche at the inaugural summer of Naropa Institute, Boulder, Colorado, 1974

Jack Kornfield, Naropa Institute, 1974

Joseph Goldstein in the 1970s

With teaching assistants outside the “lecture hall,” Boulder, Colorado, 1974

Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, Boulder, Colorado, 1974

Teaching on the Bhagavad Gita at Naropa

Hanuman, the embodiment of service and devotion for whom Ram Dass is named, at Kainchi

Joya in Brooklyn

Joya in the Himalayas, 1977

With Joya and Hilda Charlton, circa 1975

Lama Foundation, view from the kitchen

Anti-nuclear demonstration I attended in NYC, 1982

A young Maharaj-ji with an ancient Hanuman

At Neem Karoli Baba Ashram, Taos, New Mexico. Hanuman is adorned for the 2018 Guru Purnima festival.

Barbara Durkee with her children at Lama Foundation, circa 1970

I knew what Maharaj-ji really meant. If, from my soul, I saw someone as a soul, I could love him or her as a soul, as part of God. On the other hand, if I remained mired in my personality and my anger, I could be stuck on the karmic wheel of birth and death for many more lifetimes.

Maharaj-ji called for someone to bring a cup of milk, which in India is always warm milk, usually with a little sugar, almost like mother’s milk. He handed me the earthen cup. I drank some of it.

He said, “Give up anger. If you try to give up your anger, I’ll help you with it.”

For me to give up the anger, I had to give up my whole position, all my reasons for being angry. My pride. But it’s hard to be angry, drinking mother’s milk from the guru. I looked over again at the western satsang. Now they weren’t whiners. They were luminous beings with light coming out of them, and I loved them all. What was in that milk?

Maharaj-ji had done it to me again, confronting me with my negative emotions, anger and jealousy and self-righteousness, which were keeping me separate from him and everyone else and from God. I’d been wallowing in self-pity—not to mention self-hatred and unworthiness, which of course I was projecting onto everyone else. Maharaj-ji just sat there twinkling, an unflinching mirror.

I knew I had to make amends to my satsang brothers and sisters. Maharaj-ji’s essential teaching is to feed everyone and love everyone. I took an apple and cut it up. Then I went from one member of the satsang to another. Maharaj-ji said you should feed others with love; if you feed someone in anger, it’s like giving them poison. I looked each person in the eyes, until I could see the place in them where we are love together, and then I fed them each a piece of apple. It took a while. The whole situation was Maharaj-ji’s lila, his play, from start to finish.

Over the years, Maharaj-ji’s satsang has expanded to many thousands of devotees, people who were with him in the body and people who weren’t. But there’s a special photo from that year, 1971, which we call “Nainital High” because it looks like a school graduation photo. We hired a photo wallah from one of the tourist shops, who showed up at the hotel with a big ten-by-twelve-inch plate camera from British times. He set up the camera under a big black cloth. The lens had no shutter. To make the exposure, the photographer took off the lens cap and counted. Anyone who moved came out blurry.

It’s a treasured image because it represents a shared moment basking in Maharaj-ji’s unconditional love. For most of those in the photo, that time is a deep fountain of faith and solace. Since those days together, there have been illnesses and deaths, terrible accidents, painful divorces and infidelities, problems with kids and careers, addictions, and now the depredations of age. Each of us, in our unique way, confronts the existential elements the Buddha laid out, of suffering, impermanence, and the ego delusion of any permanent self. But behind it all, still, is Maharaj-ji.

Love everyone, serve everyone, and remember God.