Romance, the River, and a Few Close Calls

The war picked up again outside Paris with a battle at Andelot, a town northeast of Chaumont in the Champagne-Ardennes region, just east of the Marne River. Commandant Jean Fanneau de La Horie’s tank regiment took the town and some 800 prisoners, who were seated in rows, elbow to elbow, in a meadow when Toto and Raymonde arrived. It was too much for one regiment officer, a Jew whose family had been deported to concentration camps. He ran toward the German prisoners and began slapping and kicking them individually, going down the line. His friends brought him gently away, and he collapsed in tears.

Between Chaumont and Andelot, Edith and Lucie were driving down a narrow road, closely watching the forest for a sign of the enemy. They came out of the woods into a clearing, a muddy field where a tank regiment was beginning an attack on a German-held village. A couple of division soldiers waved them over to tell them there were some injured soldiers down a dirt road a few hundred meters back. They needed to turn around, and Edith got out of the ambulance to guide Lucie. The shoulders of the road might be mined, and so they had to be careful not to go off the paved surface. Soldiers in a vehicle in front of them shouted encouragement, and Lucie executed the narrow turns with precision. Edith suddenly felt her eardrums blow and saw a fountain of flames shooting up under the ambulance, which flew up into the air and landed on its nose. Lucie, ashen, was gripping the steering wheel. Edith ran over and jerked open the door and slid her out of the driver’s seat. The blast had come from an anti-tank mine designed to blow up a couple of tons of armored steel. It was in the middle of the road, where twenty or so military vehicles had already passed safely until Lucie triggered it in turning. The ambulance was shredded with shrapnel, as were both of their sacks of clothing, jammed under the front seats. The duffel bags had blocked the direct spray, saving Lucie from serious injury. She was deafened, shaken, and in shock, and soldiers in a nearby Jeep offered to take her to the field hospital straight away. Edith stared at the ambulance in disbelief, and then looked around and saw two bodies on the ground, spread-eagled. It was the young men who had waved them over. She had been standing practically next to them, and she was uninjured. She realized that the front wheel had blocked the exploding shrapnel from hitting her, but the young men had been struck straight on.1 Lucie spent a week resting in a hospital, and Edith was assigned her third ambulance of the war.

Driving across the same field, Raymonde and Toto’s ambulance got stuck in the mud. They carried metal sheets hung on the inside walls of the ambulance for that eventuality, and put them under the wheels to get it out.

Danièle and her partner Hélène Langé, known as “La Grande Hélène” to distinguish her from Hélène Fabre, were in a convoy not far behind Edith and Lucie, and they too had been warned about mined shoulders. Her tactical group had identified a circular route to use if the ambulance needed to take someone back to a treatment center. Danièle drove carefully, the convoy inching along the narrow road, both sides bordered with tall hedges, until it suddenly opened onto a wide field. On the other side of the field stood the village, where the church spire was now in flames. As they reached the field, the twenty or so tanks in front of them spread from a single line into a fan formation, heading for the village in a ballet of armored steel. It was Danièle’s introduction to combat, and she found the beauty in it somehow disconcerting. She was still a novice when she and Hélène were sent to pick up some wounded soldiers at a nearby intersection. When they arrived, no one was there. Artillery fire rained down nearby, so they clung to the sides of the ambulance “like complete idiots,” Danièle said. A Jeep pulled up and an officer with a walking stick shouted at them: “Put your helmets on! What are you doing here! Your role is not to hang around, get the hell out of here right now!” And he sped away. A soldier approached and asked if they knew who that was, and they said they didn’t. That was General Leclerc, he said. Before they had time to be impressed, shrapnel from a nearby explosion struck the soldier down. Danièle and Hélène had found their victim at their feet. They picked him up and took him to the treatment center. “It was a great lesson in movement, in usefulness, in not standing still. Leclerc gave us that lesson at the start,” Danièle said in an interview. “Action was the secret. You had to move. You couldn’t stand there wallowing in fear.”

Marie-Thérèse and her partner, Marie-Anne, also were brand-new on the job.

Marie-Thérèse recalled her first evacuation, picking up two wounded soldiers and then putting a third soldier, who was dead, in the ambulance as well. She gripped the steering wheel and cried for the dead soldier the whole way back to the infirmary. “I cried for that young man, for that young life cut so short,” she said. “It was a moral shock, I think.” When Marie-Thérèse and Marie-Anne arrived at the infirmary, set up in a school on the village square, medical battalion staff yelled at them for having transported a dead person. It was against the rules. Another division unit was in charge of picking up bodies, confirming identification and notifying families. One of the doctors said to her afterwards, “Marie-Thérèse, you’re brave but an idiot. You should have told them he died in transit.”

Marie-Thérèse wrote her family that she had simply wanted the soldier to have a decent burial. And he did. When the village priest buried the soldier later that day, all the village inhabitants turned out to honor him, though he was a complete stranger to them.

The division continued in an eastward direction, liberating Vittel, the prewar spa town. Its previously chic hotels had been turned into barbed-wire prison camps for thousands of British and American women civilians caught in France when their nations joined the war. Leclerc greeted them with warmth. “In 1940, we were admirably received by the English. The Americans have given us arms. We are particularly happy that it has fallen to us to deliver you,” he said.2

Across the plains of Lorraine from Vittel, the Germans began consolidating troops from the south and west, keeping the Vosges Mountains at their backs. It may have felt like the war was over in Paris, but since time immemorial, eastern France has made the call. Patton knew it, and marched eastward with his Third Army. He was repelled at Pont à Mousson with a loss of nearly 300 men. The French Second Division advanced in a parallel south of the Americans, and met the Germans at Dompaire on September 12.

Madeleine Collomb and her partner were sent to a U.S. heavy artillery unit that was helping the French at Dompaire, as the Americans had no ambulances there and had requested backup. When they reported for duty, the American commander said, “I didn’t ask for a nurse, I asked for an ambulance driver.” Madeleine persuaded him that they were in fact ambulance drivers, but the American doctor couldn’t get used to working with women. “The doctor was so afraid for us, being women, that he went with us on each evacuation,” Madeleine recalled. “After two days, he said, look, I don’t want the death of women on my conscience. Go back to the French.”

The night before the attack at Dompaire, Danièle was talking to Lieutenant Louis Gendron, a tank commander, about life, religion, philosophy. Danièle had been a prize-winning philosophy student in high school, and she was an ardent Catholic as well. Gendron shrugged at her ideas. “He said, ‘At any rate, I’ll be dead tomorrow. I’ll be wounded, and I’ll die.’” Danièle was shocked at his certainty. She argued against his fatalism, she argued for the existence of God, she fought his conviction with weapons of eloquence and reason, but she could not shake it. The following day, the battle erupted around Dompaire. The Germans had been swinging up from a base at Epinal, attempting to attack the American troops from behind. Instead, they met Jacques Massu and Pierre Minjonnet’s tank regiments and were torn apart. Some sixty German tanks were left on the field, burnt shells.

After the fight, Danièle asked after Lieutenant Gendron. He had indeed been killed. “I felt ill,” she said. “I wasn’t able to do anything, either to help him die, or to help him believe [in God].” She doesn’t believe Gendron was suicidal. Morale in the division was sky-high at that point. “I believe his death was not voluntary, but was somehow destined,” she said. “I think it’s extraordinary to be able to have a premonition of that sort.”

Patton was so pleased with the Second Division’s performance at Dompaire that he invited Leclerc to lunch with General Wade Haislip in a muddy field nearby, and popped a bottle of champagne. His men had captured a stock of 50,000 bottles, and Patton wrote in his diary that he had distributed it to the troops. Haislip, as commander of the U.S. Army’s Fifteenth Corps, had been Leclerc’s boss since Normandy, and they had become good friends. After lunch, Patton strode over to his Jeep, laid his cigar carefully on the hood, dug into a bag, and pulled out two medals. He called Leclerc over and pinned them on, and gave him a pack of five Silver Stars and twenty-five Bronze Stars to distribute to his men for the Dompaire operation. Leclerc, who loathed fuss and praise, seemed bothered, and Haislip grinned at him. “But you have done great things for the honor of the American Army,” he said.3 Leclerc returned the favor before the end of the war, pinning the French Croix de la Legion d’Honneur on Haislip. The March of Chad Regiment also made Haislip an honorary corporal, backhanded praise from the regiment’s rugged infantrymen.

In front of the division lay the Moselle River, a 500-kilometer-long, meandering waterway that had served through history as the gateway to the resource-rich plains of Lorraine and Alsace. Patton had been there in another wet September, twenty-six years before, and knew that getting across the river was critical, difficult and dangerous. Now he wanted the U.S. Seventy-ninth Infantry to cross at Charmes, and the Second Division to traverse further south, at Châtel-sur-Moselle, a bombed-out village of some 1,400 inhabitants.

On September 15, Captains Jacques Branet and Raymond Dronne led their tank and infantry companies across the river, wading through water up to their thighs. The bridge had been blown by the Germans when they pulled back to the east. Jacotte stopped her ambulance on the western bank of the Moselle to remove the engine’s fan belt before crossing the river, as she had been taught in the mechanics course in New York. Crapette and Dr. Alexandre Krementchousky and Raymond Worms, a nurse, were with her as they drove up the river bank into Châtel and stopped beside an old hospice built atop the buried ruins of a medieval fortress. It would do for an infirmary for the medical company.

The village mayor, Pierre Sayer, greeted the French troops with enthusiasm. He was thirty-seven years old, the town doctor, and head of the local Resistance group. Châtel’s residents had heard about the liberation of Paris three weeks before, and of the Allies’ victorious sweep toward eastern France, and hoped it was their turn. Dronne sent out some men from his Ninth Company to check who was in the area, and the mayor called out the village men to rebuild the bridge. Soldiers strung a footbridge across the river in the meantime, and marked the ford crossing for vehicles with two stakes and a white cord tied across the river. The patrols brought back a few German prisoners and reports of a splintered enemy presence to the east, but nothing more than rain looked imminently menacing.

The next day, U.S. intelligence reported that 142 Panzers were massing at Rambervillers, twenty-five kilometers due east of Châtel. It was thought that their direction would be north to the city of Nancy, where the Seventy-ninth U.S. Infantry Division would be going once it crossed the Moselle. But to the south, a German Panzer company still held the town of Epinal, seventeen kilometers away and on the western bank of the river. The Second Division companies were in a precarious position, with only a few hundred men and a dozen tanks, but they decided to stay put.

Rain was still falling the following day. At the time of day the French call between dog and wolf, that elusive moment of transition from day to evening, a woman called the mayor’s home: Panzers were pouring into her farmyard! Branet radioed his tank company, and they blasted away, destroying the German tanks as well as the woman’s farm. The Germans had gotten to within a kilometer of the Second Division’s perimeter, and from there, they launched a barrage of mortars, aiming for the half-finished bridge.

Jacotte and Crapette sheltered behind the hospice’s thick wall, pinned down by the mortars on one side and a German machine gunner shooting from the other side, covering the approach to the footbridge. Wounded soldiers started streaming in, some on foot, some carried by the medical company’s stretcher bearers, until there were too many to fit in the hospice. They had to put several soldiers on the ground outside, just as the rain started up again. They covered up the men as best they could. They had the only ambulance east of the Moselle, but there was nowhere they could go until the shelling and shooting let up.

Branet’s tanks began pushing the Panzers back into the woods. The two companies opened up with all the artillery they had. Mortars echoed with deafening percussion, machine guns spat and sputtered, tracer bullets cut fiery arcs across the darkening sky. The Germans had fifteen to twenty Panzers and their heavier version, the Tiger. One of Branet’s Shermans lost its tread; another was mired in the deep forest mud, but suddenly the Germans stopped firing and seemed to pull back. Branet was pleased.

Jacotte and Crapette loaded the ambulance and drove it down to the footbridge across the river. It was quiet. If the machine-gunner was still there, he gave no sign. They handed the injured soldiers over to stretcher-bearers, who carried them across the bridge to ambulances waiting on the other side. Other Rochambelle teams would drive the soldiers to the nearest field hospital. Jacotte and Crapette made a dozen trips back and forth. At midnight, the medical company cook came and found them. He had made a rabbit stew, it had been sitting since the beginning of the attack, and they had better come eat it right now! There were a couple of cardinal rules to army life, and one of them was: Don’t upset the cook. They followed him.

But Branet got a call from regiment commander de La Horie, who was on the western side of the river. Orders were to evacuate Châtel immediately. “I thought I’d misunderstood!” Branet wrote later.4 But another Panzer brigade and two German infantry battalions were on their way to Châtel. Branet and Dronne would be encircled if they stayed on the eastern bank. Orders were clear: pull back, now.

Jacotte and Crapette had just sat down to eat by the light of a single candle, numb with fatigue. Before they could take a bite, Krementchousky threw open the door and yelled, “Drop everything, we’re pulling out!” Jacotte and Crapette piled in the ambulance. Sayer’s wife, Marie-Thérèse, and their six-year-old son, Bernard, were put in the back. Branet urged Sayer to come with them as well, but he refused to leave: he felt it was his duty as mayor to stay. A half-track—a sturdy armored vehicle that was half-Jeep, half-tank—hooked up to tow the ambulance through the river. With the rain, the river had risen too high to drive across. Branet’s tank company was behind the ambulance, and everyone moved in the dark, as silently as possible, trying not to give the enemy a fresh target.

At the western bank of the river, the half-track slipped in the mud and, unable to back up with the ambulance in tow, maneuvered around in a circle to re-approach the bank where the ground was more solid. Jacotte kept the line taut between them; that was all she could do to help get them to ground. She also kept glancing behind her. The grinding column of tanks had entered the river and was coming up fast. Could the drivers see her in the dark? Unlikely. She thought, this is the end of the ride. After all the bombings, the attacks and the bullets, I’m going to be crushed by our own tanks. The first tank in line bumped her fender and then slowed, just in time. The half-track clambered up the bank and pulled Jacotte’s ambulance with it. They had made it, by a split second.

After the war, the village of Châtel put up a granite monument to the men who didn’t make it that night. The monument names thirty-five soldiers from the Second Division, and Pierre Sayer. On Monday morning after the retreat, Sayer was carried off by a group of French militiamen, as the Nazi collaborators called themselves, and was turned over to the Gestapo. He was shot the following day, along with four other Resistance members, their bodies left in a nearby forest.5 Fifty-five years later, his son Bernard Pierre Sayer read an account of the struggle for Châtel at the Leclerc Memorial in Paris, and called to thank the ambulance driver who took him across the river that night. It was Jacotte.

Danièle and Hélène were having a difficult time with the river as well. They were asked to pick up some wounded soldiers on the eastern side of the river between Charmes and Châtel. They were to cross the river at the old Roman ford, a wide and shallow crossing that was marked in Roman times by a sculpture of a man on a horse, both riding on the back of a man-serpent. The statue, removed to a museum, had been replaced for the moment by an army sentinel. Danièle started across the ford into water about a meter deep, and Hélène, a more experienced driver, said “Slow down!” Danièle’s immediate and mistaken reaction was to brake. The ambulance stalled out and would not restart. A Jeep passed them going in a westward direction and a soldier shouted at them to move: the tank company was retreating with German Tigers in pursuit. Danièle and Hélène would very much have liked to move, but the ambulance resisted all effort. A half-track driver spied them sitting there and came to their rescue. As they were towed up the riverbank, the water spilled out of the exhaust and they were able to restart the engine. They picked up the wounded soldiers and followed the dozen tanks back westward across the river. That night, they slept in a school in Nomexy, on tables that were even less comfortable then their stretchers.

“It was the first time we had retreated,” Danièle said later. “It seemed strange to us. We had always gone forward before.”

Rosette and Arlette had arrived at Nomexy to find the town draped in Lorraine crosses and French flags. Arlette was not feeling well, and was getting very jumpy under fire. They were called to an evacuation at the village of Iqney, and followed a doctor’s Jeep through a hail of 88mm mortars, feeling like a painted target on the empty road. They found the house they were looking for, and a young boy, injured by the bombing, lay in bed bleeding. His parents stood on either side, watching him bleed to death. The doctor asked angrily why they could not at least have put on a tourniquet and saved his life. The parents were ignorant peasant farmers, Rosette said, and had no idea of what to do. She felt sorry for the boy, who died.

After another run to the treatment center with some wounded soldiers, they returned to Nomexy and found all the flags and crosses had disappeared. The division had retreated from Châtel, and the residents of Nomexy had quickly chosen discretion. “I was astounded to see the streets empty and the houses undressed in so little time,” Rosette wrote.

With the retreat, Jacotte and Crapette and the rest of the medical company pulled back to Jorxey, a village about ten kilometers west of the Moselle. Since their assignment to the medical company, which had its own Jeep, stretcher bearers, and cook, Jacotte and Crapette had only to drive the ambulance. The other Rochambelles were scattered among various tactical units and often had to do their own support work. The medical company, moving with the fighting front, generally took over village cafés to set up an infirmary. The cafés tended to be located on a square, where there was room to park the ambulances in front; they had a large room where stretchers could be laid out, and they had water. Such was the situation at Jorxey. Jacotte and Crapette had fallen into an exhausted sleep in the back of their ambulance when Krementchousky came banging on the door and said they had to get up, it was an order! They did, groaning, and found the emergency was that a local farmer’s wife had cooked up a big meal for them, with cabbage and potatoes and a mirabelle tart (it was plum season), their first proper meal in days. They ate with relish, and then slept for the rest of the afternoon, to return for more of the same fare that evening. The woman who served them was called “Tante” or Aunt, by her niece, and Jacotte and Crapette began referring to her as “Tante Mirabelle.” Two mirabelle tarts later, they baptized the ambulance Tante Mirabelle, and the good farmer’s wife assisted in the ceremony. (The name of their ambulance was later to prompt many an Alsatian to give them a bottle of mirabelle brandy, a homemade potion of some renown.) They pulled out at 5:00 A.M. the next day to retake Châtel, crossing the river via a temporary pontoon bridge the engineers had managed to put up. This time, the Germans began launching mortars at their very approach, and it was hard fighting to retake the town.

Edith and Lucie, newly released from the hospital, caught up with their Spahi unit at Nomexy. They parked their ambulance behind the house closest to the river, and ran, heads down, with their stretchers to pick up the wounded soldiers on and around the footbridge. The infirmary behind them was in a school, and it was rapidly filling up with the injured. Then the hail of mortars started marching right across the river toward their ambulance. Lucie ran for shelter and Edith got the ambulance out of there fast, just as a shell destroyed the house they had been using for cover. She drove toward some garages they had seen, thinking they might provide a good place to park, and found Lucie talking to a young soldier in the doorway of one of the garages. As she approached, the soldier lit a cigarette and Lucie leaned over to light hers off the flame. At that very moment, a jet of blood spurted from his neck and he collapsed, dead. A fragment from an exploding mortar had sliced his jugular. Lucie covered her eyes with her hands and went rigid with shock. Edith pulled her down into a homemade bunker where some local residents were hiding, and stayed there with her, talking her back to a state of calm.6 Lucie was having a few too many close calls.

Jacotte Fournier (l) and Crapette Demay in front of a stack of fertilizer in Lorraine.

And she wasn’t the only one. A couple of American officers, driving up in a Jeep while Nomexy was under attack, were hit by a mortar. One of the men had his leg blown off. Raymonde Brindjonc took his necktie for a tourniquet to stop the bleeding (“I always used their ties as garottes,” she said). The man was conscious, but heavy, and as Raymonde tried to pull him over to the ambulance, they fell into a ditch. As they rolled down, a mortar slammed into the place they’d been standing a moment before. Both of them would have been killed if they had not fallen. Years later, the American officer told a division veteran that he had never forgotten the big blue eyes of the woman who saved him that night.

At Epinal, the U.S. Fifteenth Corps attacked the remaining Panzer divisions and sent the survivors flying for the shelter of the Vosges Mountains. The division pushed the Germans out of Châtel as well, and the columns of tanks moved out in an eastwardly direction.

Tank company commander Captain Jacques de Witasse, meanwhile, had broken a couple of ribs and separated his collarbone in a Jeep accident, and like many before and after him, plotted his escape from the hospital when it was time to be transferred to the rear. He was transported in an American ambulance, supposedly driving from Vittel westward, but he directed the American driver eastward instead until they arrived at his company’s camp near Charmes. “The American ambulance driver quickly understood that he had been had, and furious, started letting loose imprecations in the best Texas style,” Witasse wrote. “To calm him down, the Austerlitz [tank] crew gave him a marvelous reception in which the Lorraine mirabelle had a leading role. The American left several hours later, completely happy, and alone in his ambulance, which seemed to have a tendency to weave a bit as it headed in the approximate direction of Vittel.”7

After Châtel, Georges Ratard took Arlette to see a division doctor, who confirmed what she already knew: she was pregnant. Georges wanted her to quit, and she was ready. She said she didn’t mind leaving the Rochambelles in the middle of the war. “I was happy,” she said. “I didn’t regret leaving, because I was expecting a son.” She was convinced from the start that the baby was a boy, and that was important to her. Arlette was Rosette’s second partner, after “You” Guerin, to leave the Rochambelles because of pregnancy.

Toto’s only comment was that if Arlette had come to her sooner, she would have helped her avoid a pregnancy just then. Arlette later said she was utterly naïve at the time, that she didn’t have a clue how to avoid getting pregnant, and wouldn’t have tried anyway. Rosette, however, said that on the day of her wedding, Arlette asked several Rochambelles how to prevent pregnancy, and no one knew. They told her to ask Toto, and apparently she never did. Innocence bordering on ignorance was close to the rule among the women. Rosette recounted that one afternoon in a soldiers’ cantine, a fellow stuck his head in the door and said, “Quick, they’re distributing the capotes anglaises!” (Literally, this would be an English bonnet, but was also slang for condom.) One of the Rochambelles stood up and said “Great! I don’t have anything to wear!”

The army wasn’t much more sophisticated than the ambulance drivers. When Arlette returned to Paris for demobilization, the army had no procedure for discharging a soldier because of pregnancy. “They didn’t know what to do,” she said. They took her military clothing, so she didn’t even have a coat. Elina Labourdette loaned her a fur-lined coat for the winter, and Arlette moved in temporarily with a cousin in the city. Rosette was assigned a new partner, Nicole Mangini-Guidon, an elegant blonde who had joined the group in Paris. Rosette was pleased to have Nicole as a partner, even though Nicole did not know how to drive. She had a wonderful manner of dealing with the injured soldiers. “I have the impression that her young and fresh beauty, and her compassion, comforts them,” she wrote. Rosette took over all driving duty, and the soldiers never knew their other “driver” wasn’t quite up to her job.

From Châtel, Anne-Marie and her partner Michette de Steinheil were sent to Zincourt, a few kilometers east, to pick up some wounded soldiers. On the way, they ran across Leclerc, who asked where they were going. They said Zincourt, and he said, go on then, giving them his habitual little push behind with his walking stick. Branet’s company was behind them, and Branet quipped over the radio: “Don’t worry, the Rochambelles are out front.” Anne-Marie and Michette found the streets of Zincourt empty, not a soul around; the village had just been deserted by the Germans. Then residents started coming out from behind their doors and greeted Anne-Marie and Michette as conquering heroes. Branet and his tanks arrived to “take” the village and found the women having lunch in the center square. Michette said they only had to transport one man, a civilian, from that town. They weren’t supposed to take care of civilians, but if there were no wounded soldiers, it was hard to refuse.

Anne-Marie and Jacques Branet were an established couple at that point, and their affair was an open secret in the division, even if they were careful not to let it show around others. “They were very, very discreet,” Michette said in an interview. “They didn’t flirt openly.” Anne-Marie was married at the time; her husband had been active in the Resistance and then joined the First Army. But her heart was no longer in the marriage, she confided to a friend. And then she met the classically handsome Branet, who, in Leclerc’s description, was adored by his men and esteemed by his bosses. Anne-Marie did not fail to enjoy his company, and, having been married, she was not in the same state of lamentable ignorance as the others.

The war, with its inherent elements of camaraderie, courage and sacrifice, was inevitably a crucible for romance, but the women insisted that any liaisons be carried out with great discretion. The stakes were too high for both the women and the men to play around carelessly: social reputations carried consequences, venereal disease was common and pregnancy outside of marriage could spell ruin. At the same time, an undercurrent of affection between some Rochambelles and division officers was often in the air. “Of course there were people losing their hearts to each other all the time,” Anne Hastings remarked.

Other women developed deep friendships with their fellow soldiers, relationships they would not have dreamt of wrecking on the shoals of sexual attraction. For Jacotte and Crapette, their buddies became the tank crew that always seemed to be right in front of them in convoy. Malmaison’s crew was led by Lieutenant Eric Foster, who was half English and half French, and included Drouillas, a Chilean; Chevalier, a Swiss, and Jacques Salvetat, from the south of France. One afternoon, the Malmaison crew invited the two women to “tea.” They all pretended to be in an extremely elegant environment, instead of sitting on a board in a muddy field. Salvetat peeled an apple for each of them and the women offered them cigarettes, which everyone was running low on at that point. “What a privilege it was to get to know them,” Jacotte said. “They were boys of great character.”

And even if one of them was sweet on Crapette, and everyone knew it, nothing was ever said or done. “We never had the slightest flirtation with the boys. There was no misunderstanding,” she said. “We were friends, that’s all. There was never any hand-holding or smiles. It simplified things that way. They considered us as untouchable.”

Had they been further back in the line, possibly there would have been time and inclination for flirting and seduction. But they were on the front. “We couldn’t have done what we did if we had had other ideas in our heads,” Jacotte insisted. Jacotte’s viewpoint was that of the majority of the women. Toto and Anne-Marie, both separated in distance and affection from their husbands, were exceptions.

Danièle, for example, had never been permitted to wear her hair down. When she joined the division, she wore her waist-length braids wrapped around her head, in the Alsatian style. The mores of the time dictated that she could go to war, but she could not wear her hair loose. It would have been considered an indicator of her moral condition. “We were very naïve in that era,” she said. “On one hand we were raised with sort of Scout ideals, that counted a little, as did the religious education of the time. The attitude of the girls was very important. Madame Conrad did not accept just anybody. All the girls were very well-mannered. We always said, ‘We are not A.F.A.T. [the auxiliaries]! We are Rochambelles.’”

Danièle noted that the women and men vous-voyéed each other, a linguistic device the French use to create distance and demonstrate formality, rather than the casual and informal “tu” form of you. “We were with 20,000 men and not one of them would have touched us,” she said. Janine Bocquentin seconded Danièle’s assessment. “We were friends and comrades,” she said. “I never heard of girls who slept with the boys. We weren’t there for that. We were there to experience an extraordinary moment, in my case at any rate. It was a great adventure.”

Friendship amongst the women also was cemented by this time. They had stood the test of combat, and the knowledge that they could trust one another with their lives forged links that never would be broken. Rosette wrote her mother from Lorraine, where the farmers maintained pungent stacks of fertilizer, that she was deeply satisfied. “This morning, walking in the stinking streets, I suddenly realized how happy I am with the life I’m leading, how warm it is in friendship, how rich it is in surprises. What a fine job it is to help men who are suffering. It is easy to overcome fear when you have a precise task to accomplish and you try to do it to your best ability.”

Rosette didn’t hesitate to dive right into action if she was needed. Captain de Witasse recalled a day of fierce fighting near the village of Anglemont, when one of his tanks was hit and called for an ambulance. Nearby, de Witasse could see Rosette, whom he described as “young and ravishing,” but he was reluctant to send her into the middle of the firefight. He didn’t need to. “Rosette heard the call for help on the radio. She headed down the road, crossing the barrage of German artillery encircling Anglemont (that day the artillerymen were firing with heartfelt enthusiasm on both sides), and returned a little while later, under the same conditions, with an ambulance full of wounded.”8

Not everyone in the medical battalion was so stoic. Rosette recalled one doctor whose talent for disappearing at the first sight of danger was well known. He tried to reprimand her for a cracked windshield on the ambulance, which had in fact occurred because of a small accident. Rosette didn’t feel like owning up to yet another accident, so she said a machine gun had done it. The doctor called her on it, saying the crack was nothing like the damage automatic weapons fire makes. “How would you know?” she snapped. The doctor turned pale and left.

The Rochambelles’ tactical group changed commander for the fourth time after Châtel, when Colonel de Billotte was sent to Paris to organize and train a new battalion of Resistants. The new commander, Colonel Jacques de Guillebon, a graduate of the elite Polytechnique School, was quickly characterized by his haughtiness. “Our Rochambelles, in whom the sense of observation was tightly allied to that of humor, awarded him the nickname ‘Bec d’Ombrile (Umbrella Nose),’ which has stuck ever since among us,” Witasse wrote.9 Rosette explained that Guillebon had a habit of standing stiffly, with his nose in the air, and communicated with the lower ranks as little as possible. The nickname was his reward.

Patton and Leclerc were ready to drive straight to the Rhine, continuing the fast-moving momentum that had spelled their success up to now. But the food, munitions, and gasoline supply line had not kept up the pace. They were short on all counts. Patton estimated that his army was lacking 140,000 gallons of gasoline, and he was told that 3,000 tons of supplies were being diverted to Paris on a daily basis to support the civilian population.10 Patton raged and fumed at the Allied command’s inability to furnish his troops with what they needed, but nothing he did had any effect. For most of the month of October, the Allied forces sat in the mud and rain of Lorraine, giving the Germans time to regroup, resupply, and reinforce their defenses. Leclerc was as frustrated as Patton.

“Leclerc spent a month being unbearable,” Danièle recalled. “He was dreadful, all the time at his maps. He strained like a dog on a leash.”

On top of the downtime, Leclerc was ordered to detach from Patton’s Third Army and put his division under the orders of U.S. Major General Alexander Patch’s Seventh Army. Leclerc didn’t know Patch, but was reassured by the fact that General Haislip also was transferred to the Seventh Army.

For the long wait, a half-dozen Rochambelles were assigned to stay at a deserted village called Roville-aux-Chênes, but upon arrival they found the tank crews had already occupied all the comfortable housing. Toto requisitioned the combined village hall-school building for sleeping quarters for the women. Some Second Company soldiers, feeling a bit guilty, helped them sweep and clean out the room, and the women worked hard getting it in shape. As they were finishing, a couple of soldiers from the Austerlitz tank crew, having found uniforms in the hall attic, disguised themselves as firemen, put on false mustaches and masks, and knocked on the door. “Putting on a ‘gendarme’ accent, they demanded to speak to ‘Madame la Commandante,’” Witasse wrote. “Toto arrived and they explained that the village hall could not, under any circumstances, become a house of ‘working women.’ Therefore they had to leave the premises, right away. Out! Toto exploded with a fury that was in no way pretended. Her girls, upset, formed a circle around the two rogues, and, equipped with brooms, became absolutely threatening. The two fellows pretended to try to escape, and then pulled off their mustaches. It ended in a gigantic burst of laughter.”11

Toto and the women spent several days resting and trying to find food in neighboring villages, and eventually invited some officers and tank crews to dinner. They realized, to their dismay, that the men’s meals were far better than the women’s: the tank regiments had support personnel assigned to forage duty. The foragers hit a wide-ranging territory, buying or stealing—whichever was necessary—chickens, ducks, whatever produce the local farms still had available. The ambulance drivers had no experience in this, and mostly confined themselves to being creative with K-rations. Witasse wrote that the combined lunches and dinners nonetheless inspired the men to clean up a little. “Our ambulance drivers were often invited by the tank crews, who, on those occasions, made a great effort to receive them in a dignified manner. A kind of competition developed, which brought about the happy effect of obliging the personnel to put on clean clothes, and allowed us to establish the bonds of friendship, so precious in combat.”

At Roville, the women also had frequent musical evenings of singing popular songs and duets. Marie-Thérèse remembered Lucie, Michette, and Raymonde as having particularly good voices. Some of the division officers also would join in.

One October day Florence Conrad arrived to summon Toto back to Paris. The army was trying to organize its women’s corps and had decided to cut Conrad’s four stripes of a major to the two stripes of a lieutenant, and take Toto from two stripes down to one. Conrad had assigned herself and Toto their ranks at the beginning of the Rochambeau project, and they had sewn their own stripes on. Neither of them were about to take any off. Toto went to Krementchousky, who sent her to Leclerc. Leclerc sent a blistering letter to Paris confirming their ranks in the division. Florence and Toto went to the A.F.A.T. headquarters and were sent from office to office until they finally ended up in front of the commandant, Hélène Terré, who had received Leclerc’s opinion. Their stripes were reluctantly confirmed, and Toto returned to the front.

When she got back, she found Edith asking for a change of partner. Edith later said she had finally figured out what the rest of the Rochambelles already knew: Lucie was a lesbian. “It took me a long time to understand. I just didn’t get it,” Edith said later. Lucie did not try to hide her sexual orientation, and the other Rochambelles said it had never caused any conflict in the group. Lucie had been married and had left her husband after an affair with another woman. When she wasn’t having near misses with death or being reprimanded by her commanding officers, she was a lot of fun, and Edith missed her afterward. “She was terrifically cultivated. I missed her because she was so funny,” she said.

Lucie also was fast, and the faster you got the soldiers onto the stretcher and out of combat, the safer you were. Edith found she was pretty quick, too. “I had discovered that I was quick, that I wasn’t afraid, and that I managed to do my work well.”

At Roville, the Rochambelles were assigned a new driver who had tried to join the war as a regular soldier. Michelle “Plumeau” Mirande had worked with the Resistance during the occupation, and when her group joined the division, so did she. One day, she was on guard duty when Leclerc happened to walk by and ask her a question. She responded, and he jumped and said that that was a woman’s voice. “But I am a woman, General!” she replied. She was sent directly to the Rochambelles, furious to be sidelined as a driver. Plumeau, so nicknamed because of her feathery hair, didn’t want to join a women’s unit. “But when she understood our work, she accepted it,” Raymonde said.

With little to do to fill the days, Rosette went shopping. In Nancy, the nearest big city, she bought some fur-lined gloves, socks, and insoles for her army boots, which were too large for her feet. She and everyone else in the division complained that the GI-issue boots absorbed water like a sponge. She also got a plaid scarf, but Toto didn’t like it and Rosette wasn’t allowed to wear it when Toto was around. Toto could be overbearing about the women’s personal appearance: she told Janine Bocquentin that she wasn’t feminine enough, and to make more of an effort. Janine shrugged her off.

In a village near Roville, they found a public shower, and Rosette was in line behind a soldier whose boots and socks gave her pause. “I confess I was a little afraid when I saw the state of his feet. He hadn’t taken off his socks since Paris!” But for a shower, that rarest of comforts, she braced herself and went ahead. While at Roville, Rosette and Nicole named their ambulance Bessif (The Force) to stay in keeping with the other “Moroccans,” whose ambulances bore Arab names such as Baraka (Blessing) and Mektoub (It is Written). Rosette said she never followed through with painting the name on the ambulance. She felt part of the “Moroccans” because she had joined from there, but she was not an Arab speaker and had only lived in Morocco for three years before the war.

The rain did not stop falling, the ever-present stacks of fertilizer left a permanent odor in the air, and everything, everywhere, was muddy. Jacotte said that one night her boots were so caked with mud she couldn’t get them off, so she hung her feet off the edge of a bed and slept on her stomach. They began putting snow chains on the ambulances to get them out of the muck. Marie-Thérèse remembered gathering branches and small logs to build a wooden platform behind the ambulances so that they could arrange their blankets on the stretchers to sleep at night. Without the platform, the stretchers sank into the mud. Once wrapped, with one blanket on the bottom for insulation and two blankets on top for warmth, they slipped the stretchers back in the ambulance and climbed inside to sleep.

Anne Hastings (standing) and Anne-Marie Davion checking the oil in their ambulance.

“It is so wet that we have to winch the tanks up hill,” Patton wrote. He was bivouacked to the north of the Second Division, waiting for the rain to clear so that the bombers could flatten the fortress at Metz. “Metz, the strongest fortress in the world, is sticky but we will get it as soon as we can get the air.”12

Finally, at the end of October, Leclerc got the green light from Haislip for an attack on Baccarat, home of the crystal factory and core of a German command center that defended Alsace to the east. Leclerc decided to attack through the Mondon Forest, north of the town, and his unexpected approach coupled with extra heavy artillery crushed the Germans there. Marcelle Cuny, a young woman Maqui fighter, rode in the commander’s Jeep to lead the tactical group into Baccarat by the back roads, mortars falling all around them.

Edith was now partnered with Anne Hastings, the French Harvard student who was married to an American. One day they were driving on a narrow track in the Mondon forest toward Brouville, expecting an ambush at any moment, wondering where the Germans had gone. A couple of tank soldiers on a rise at the edge of the forest signaled to them, and they tried to drive over, but the grass was too wet and the tires slid. They got out and climbed up on foot. The soldiers were part of a tank unit, and their lieutenant had taken a direct hit by a shell. His torso was hanging out the top of the tank and his legs were in the bottom. They helped get him out and laid him on the ground, which ran red with blood. Edith and Anne wiped their hands on the wet grass, shaken and upset, and returned to their ambulance. There were men still living who would need them, and all their concentration had to be funneled in that direction.13 They found the fighting centered on Brouville, where the German and French troops dug in to pound each other with shells through the rain and mud. For several days, the ambulance drivers slipped up and down the dark forest roads, carrying the wounded to treatment centers, and the mortars fell in the incessant rhythm of the rain.

Christiane Petit and her partner Ghislaine Bechmann, who had joined the group in England, were attached to the Spahi reconnaissance unit along with Dr. Benjamin Moscovici, a Romanian, who referred to his female ambulance drivers as “drôles de cocos,” or funny kind of guys. Because they did reconnaissance, the Spahis were far in front of the rest of the division, and after one mission at Nonhigny, the ambulance drivers had to take wounded soldiers through a no-man’s-land to an American field hospital. An undefined space between the lines was the worst place to be. They could as easily be shot by their own troops as by the enemy. In the darkest parts, Ghislaine walked in front of the ambulance with her fingers muting the glow of a flashlight to give minimal guidance. Christiane was relieved when they reached the hospital, where they surprised the U.S. Army staff. “The American who met us, I can still see his face,” Christiane said in an interview. “Two girls, twenty-five years old, who arrive out of the middle of the battle with all our wounded. He said, ‘We don’t have any girls here.’ There weren’t any anywhere.”

After their work there, the commander of the Spahis’ regiment gave Christiane and Ghislaine the honor of permission to wear the Spahi’s red cap, citing “courage admired by everyone.” They also received citations for their evacuations “under particularly violent fire” at Nonhigny. Christiane enjoyed wearing the cap a little more than Toto thought she should, and this led to Toto’s Rule No. 41: When sent temporarily to another unit, do not insist on wearing that regiment’s headgear when the lieutenant is patrolling nearby.

Another day, Christiane and Ghislaine were called to take Raymond Fischer, a division soldier, to the hospital. He was suffering from hepatitis and was badly dehydrated. Fischer, who had signed up with the division in Paris at the age of eighteen, became obsessed with getting some tea. He wrote in his memoirs that Christiane and Ghislaine tucked him into a stretcher between their two twin beds for the night before leaving for the hospital, and brought him some tea. “Divine nectar, sublime brew, served by the Graces, and though it did not render me immortal, as the Greeks would have wished, it revived my will to live. And in that feminine barracks, I was filled with bliss.”14

Fischer, a native of Alsace who had hidden in Normandy to escape conscription into German ranks, drove one of the medical battalion’s armored halftracks, which picked up wounded soldiers in conditions under which the Rochambelles’ nonarmored ambulances should not go. He said in an interview that he heard about the Rochambelles before he met any of them, as they had a tall reputation in the division. “Their name ended in ‘belles’ and they often were. The officers liked them a lot, and the Rochambelles had a slight favoritism toward the officers,” Fischer noted with the wry resentment of an enlisted man. Having women in the division was “marvelous,” he said. “If anything happened to us, we knew we had devoted women by our sides.”

The attack on Baccarat signaled a return to the roar of pounding artillery, shells smashing down for hours on end, bullets zinging past any rounded corner. But the division was delighted to get moving again, and so were the ambulance drivers. One day Toto and Raymonde picked up a wounded soldier from a field and then saw that the German gunners who had hit them also were dead, except one, who was injured. They put the wounded German in the ambulance with the wounded Frenchman, who immediately started protesting that he wasn’t going to share his ambulance with the enemy. Toto gave him a generous shot of morphine and he passed out.

The Rochambeau Group often took German wounded to hospitals. “The poor kids, fifteen, sixteen years old, shot full of holes…” Jacotte remembered. However, some were not poor kids at all, but dedicated Nazis, as Jacotte discovered. One day she was asked to transport a dozen German prisoners in her ambulance to the rear of the American lines. She didn’t like the look of one of them, and though the prisoners had been searched by the French soldiers, she checked his pockets again, and found a grenade. “Then, we had the feeling they were the enemy. Then, they could go jump on a mine and I wouldn’t care,” she said.

Marie-Thérèse picked up some German teenagers, sixteen and seventeen years old, outside Badonviller. “They were blond, they were young, you would have called them children. And they cried, calling ‘Mother, Mother…’”

And sometimes, in the back of an ambulance, the French soldiers were able to overlook their differences with the Germans. Anne Hastings recalled having several wounded French and one injured German with her one day. She asked if they were hungry, and the French men said they were, so she gave them food. And the French soldiers said, “What about the Fritz?” “Fritz” was a slightly less rude way of referring to the Germans than “boche.” “I gave them cigarettes—as though that were good for their health!—and again they said, ‘What about the Fritz?’ And I thought that was quite nice. It made things less nasty,” she said.

Baccarat was at last liberated on October 30, and Leclerc was pleased with both the speed of the campaign and low number of casualties the division had suffered. With the town in friendly hands, Edith and Anne went to visit its renowned crystal factory, tramping in with their muddy boots and bloodstained uniforms, and felt the intensity and fragility of beauty in a way they never had experienced before. Edith recounted the piercing contrast between the filthy horror of the war and the brilliant fineness of the vases and goblets around her. “Here, all was light, beauty, creativity, while outside, all was ugliness, ruin and suffering,” she wrote.15 Marie-Thérèse bought her family a seventy-six-piece service of Baccarat glassware at the factory and had it shipped to Paris.

Even when the battle was over, explosives buried in the mud remained treacherous. A soldier stepped on such a mine, and Marie-Thérèse and Marie-Anne were called to take care of him. The American field hospital was set up in a high school at Lunéville, northwest of Baccarat, but the Rochambelles were not supposed to go there. They were required to take the injured to the treatment center closer to their lines. Marie-Thérèse decided to ignore that rule and take the soldier straight to the hospital at Lunéville. He was badly wounded in both arms and legs, and the women had could not stop the hemorrhaging. At the hospital, the American nurses—all men—carried him directly in to surgery, but the doctor was not optimistic about his chances for survival. The women left and had no news of the soldier afterward. They believed he had probably died, but that they had done their best for him.

The war also had its lighter side, and for Marie-Thérèse and Marie-Anne, it was a moment of warmth and respite in an old farmhouse outside Baccarat. It had an old-fashioned fireplace in the middle of the large common room, and the inevitable stack of fertilizer in the courtyard. The Lorraine farmers measured their wealth in the size of their stack, and this one was stinking large. The farmhouse owners apparently had fled the Nazis, and had tried to hide their stores before leaving. Some division soldiers did not take long, however, to find the entrance to the cellar hidden under the stack of fertilizer. Along with some fine bottles of wine, they found urns full of butter and goose lard and sacks of potatoes. They caught a dozen or so chickens, wrung their necks, plucked their feathers and put them on a roasting spit over a big fire. They fried the potatoes in a big washtub full of fat, a treat the French hadn’t had in the lean years of occupation. It was a veritable feast, and Marie-Thérèse and Marie-Anne were the only Rochambelles around to enjoy it.

At the end of the meal, the men brought out some mirabelle brandy they had found, and poured shots for everyone. Just then, a couple of soldiers burst in the room: a patrol had been hit, and there were wounded to evacuate. One of the men at the table said that since women don’t down their brandy in one shot, they could pass theirs over to him. Naturally, Marie-Thérèse and Marie-Anne stood up and shot the potent brandy. Then there was work to be done, and Marie-Thérèse, who was utterly unaccustomed to heavy drinking, insisted on carrying out her duty.

“Marie-Anne,” she pronounced carefully, “open the barn door.” She drove the ambulance out of the barn and picked up a doctor to accompany her, as Marie-Anne sensibly bowed out of the mission. The doctor shouted as Marie-Thérèse drove over an anti-tank ditch and straight on without blinking. They got the soldiers, who were not too seriously wounded, and drove them to the treatment center. The doctor hopped out of the ambulance at the center and requisitioned some strong coffee for Marie-Thérèse. He wasn’t risking the ride back on the fumes of mirabelle brandy.

Toto had a bad cold and a worse case of the blues one afternoon in mid-November, stuck in a convoy held up between Baccarat and Badonviller, and decided to go sit in a rare patch of sunshine on a village square. She took out her jackknife and sat on the edge of a wall, cleaning her fingernails, when an infantry soldier approached, laughing, with a fashion magazine he had found in the ruins of a house. He opened it and pointed at a photograph: there was Toto, in a long white evening gown and gloves, perfectly coiffed, bejeweled and elegant. “It was very funny to see Toto in such a different life,” Raymonde said. They laughed over it, and Toto kept the magazine.

In fighting around Vacqueville, a village northeast of Baccarat, Jacotte and Crapette’s ambulance was shot straight through. Crapette caught some fragments, but wasn’t seriously injured. They were glad the back of the truck was empty at the time. A few minutes later, the back windows of the ambulance were blown out by the percussion of antitank cannons shooting from their side. The women covered the windows with cardboard. The following day, the Malmaison tank crew member Jacques Salvetat came round to the infirmary and squatted quietly in the corner, smoking his pipe, and Crapette said, “So, Salvetat, what can we do for you today?” He replied, “Umm … we were worried about you yesterday.” He wanted to be reassured that they were fine. Crapette and Jacotte smiled and told him not to worry. They were touched by his concern, but felt they were in no more danger than anyone else in the division. The next evening, they were asked to take a woman about to give birth to the hospital in Baccarat, and upon their return, found the house where they had been staying flattened by a mortar.

As the division liberated villages along their path, village residents returned to their homes. Marie-Thérèse, writing in a November 7 letter home, remarked that she felt tremendous sympathy for them. “I will never forget the scenes we are now seeing, these poor people returning to their villages, pushing their poor little handcarts, and finding nothing, or almost nothing, and yet thinking to hang a flag on what remains of their houses.”

Badonviller was one such town, and the fighting there was fierce. Zizon and Denise were near Badonviller one afternoon when a soldier on a motorcycle asked them to evacuate a badly wounded member of General Leclerc’s guard unit. The route was still under fire, but they raced behind the motorcycle through the bombing and found the soldier. He had been shot in the heart and both arms, caught by a horizontal spray of machine-gun fire. They got him into the ambulance, and Zizon sat behind the wheel, with him holding desperately onto her hand. She was trying to maneuver the ambulance around craters in the road to avoid aggravating his injuries, and it wasn’t easy to do with just one hand, but the soldier would not let go. “Let me hold it, you know very well that I’ll never hold a woman’s hand again,” he said. Eight kilometers down the road, they unloaded him into a treatment center, and the doctor on duty yelled at them for having run the risk of picking him up. “Can’t you see that he is going to die?” the doctor said. Denise responded with vehemence that their job was to pick up the wounded wherever they were, not to make life-and-death judgments in advance. The bitter exchange ended cordial relations with that doctor for the rest of the war. The ambulance was so bloody that Zizon and Denise had to wash it down with buckets of water and throw out the stretcher before returning to their post. “On the way back, I cried like an idiot, collapsing under the weight of so many deaths. Denise just said to me calmly, ‘How many will you have to see die before you can manage some serenity?’”16

Newly promoted to lieutenant colonel, de La Horie led his troops into Badonviller on November 17 in a surprise attack on two German battalions there, killing 200 men and taking 600 as prisoners. The next morning he stopped his Jeep to speak briefly to Marie-Thérèse. They often had conversations on literature or history, the kind of talks that were food for the soul for intellectually starved Marie-Thérèse. De La Horie was “charming, cultivated, and good-looking, and also married and a good husband,” she said later. That morning he told her that things were heating up nearby, and that he had to go. Jacques Branet was among the soldiers in a Jeep behind him, and they drove off to the village of Brémentil, three kilometers north. The officers were standing in a house, discussing plans, when a mortar blasted through the window and exploded at their feet. Branet got up, dazed, and found de La Horie unconscious. Krementchousky happened to be there, and he threw de La Horie into his Jeep and raced for the infirmary at Badonviller. On the way he passed Leclerc’s car, en route to a meeting with de La Horie. They were all too late. The colonel was dead; a piece of shrapnel had pierced his heart. Leclerc and de La Horie had been classmates at the St. Cyr military academy, and they had made the long march across North Africa together. Leclerc went to say goodbye, kissing his old friend on the forehead before turning heavily back to the war.

The news flew rapidly through the division, and Anne-Marie ran into the infirmary, crying and shouting. “De La Horie is dead, and Jacques is, too! I have to go see Jacques!” A couple of ambulance drivers calmed her down. Branet was not dead; he was fine. It was the only public display Anne-Marie ever made over Branet, whose discretion in her regard was extreme. “He was a little cold, even with her,” said Marie-Thérèse. “I never saw any gesture that could be translated into tenderness or affection. He was a good-looking man, very old France, from the Parisian bourgeoisie, very distinguished.”

Anne-Marie and Marie-Thérèse had attended the same Catholic school and had belonged to the same Scout troop when they were teenagers, and now by coincidence were in the Rochambeau Group together. But Anne-Marie never confided anything about Branet to Marie-Thérèse. She did talk to Toto, however, and Toto tried to help her. Anne-Marie wanted very much to marry Branet, but his ultra-Catholic family opposed the match, as she would be a divorcée.

The same morning that de La Horie died, a battle erupted at Petitmont, the next village up the road from Brémentil. Michel Phillipon, radioman on the Montereau II tank, wrote that he was in a convoy of tanks, followed by a couple of ambulances, when they fell under attack. The lead half-track (HT) was hit, with one man dead, three badly wounded, and the vehicle on fire. Then shells hit the tank Iena, killing three men and injuring two. The tank also started to burn. “Courageously, the Rochambelles went to get the wounded from the HT. They wrapped them in blankets, and placed them provisionally on the grass, waiting to be able to evacuate them. Then they came to load up Dornois and Dollfus [crewmen from Iena].”17 The remaining tanks opened fire, and by nightfall the village was theirs, and the wounded soldiers were recovering in a field hospital. Fighting in the area cost the division nearly 300 casualties.

The soldiers were young, some of them not even the eighteen years required to join the army, some of them away from home for the first time. Military culture tends not to leave room for emotions of sadness, fear, and loss, while those were often precisely the emotions of a war experience. The young men came to the Rochambelles for moral support, for encouragement, for telling secrets, and for shedding tears. Marie-Thérèse remembered two childhood friends who enlisted in Paris, and who told her the story of their lives: They had loved the same girl, and she had chosen one of them, and instead of the choice destroying the friendship, it had made it stronger. In Lorraine, one of the young men was killed. The surviving friend came to Marie-Thérèse and wept long tears of grief on her shoulder. He was nineteen years old. “He needed a compassionate heart, a friendly ear,” she said.

As the division wrapped up the area around Baccarat, winter began to close in. The first snow had fallen and stuck on the ground, and the tank regiment began confiscating white tablecloths and bed linens from villagers to camouflage their vehicles. Patton’s troops had finally taken Metz, after a twelve-day assault and 2,000 bombing runs, and were moving into the northeastern corner of France towards Belgium.18 Another U.S. unit came up from the south to meet the French at Vacqueville, in the foothills of the Vosges Mountains. The infirmary was the only room with a table, and the American and French command staffs spread their maps out there to consult before going their separate ways. An American officer kept taking a draw from a whiskey flask every time artillery hit nearby, and offered some to Jacotte and Crapette. They refused. It was 7:00 A.M.; they hadn’t yet had their coffee. Besides, Jacotte said later, had they needed a drink every time they heard a little artillery, they would have been drunk throughout the war. And they had work to do.

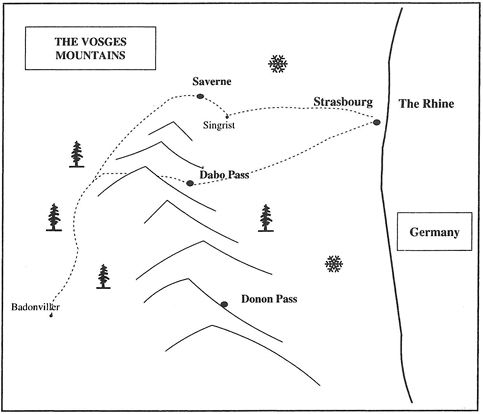

The Rochambelles’ route to Alsace, November 20-23, 1944