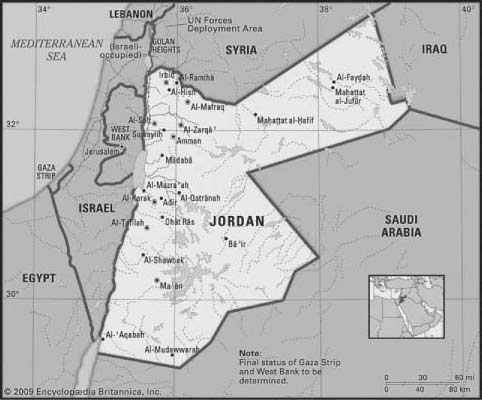

Jordan, situated in the rocky desert of the northern Arabian Peninsula, is a young state in an ancient land. It is bounded to the north by Syria, to the east by Iraq, to the southeast and south by Saudi Arabia, and to the west by Israel and the West Bank. The West Bank area (so named because it lies just west of the Jordan River) was under Jordanian rule from 1948 to 1967, but in 1988 Jordan renounced its claims to the area. Jordan has 16 miles (26 km) of coastline on the Gulf of Aqaba in the southwest, where Al-‘Aqabah, its only port, is located.

Within Jordan’s borders lie the biblical kingdoms of Moab, Gilead, and Edom, as well as the renowned red stone city of Petra.

Arabs account for the majority of the population of Jordan. These are mainly Jordanians and Palestinians. Bedouins form a substantial minority and were the largest indigenous group before the influx of Palestinians in the mid-20th century. Jordan is the only Arab country to have granted citizenship to its Palestinian population on such a large scale.

Jordan has three major physiographic regions (from east to west): the desert, the uplands east of the Jordan River, and the Jordan Valley (the northwest portion of the great East African Rift System).

The desert region is mostly within the Syrian Desert—an extension of the Arabian Desert—and occupies the eastern and southern parts of the country, comprising more than four-fifths of its territory. The desert’s northern part is composed of volcanic lava and basalt, and its southern part of outcrops of sandstone and granite. The landscape is much eroded, primarily by wind. The uplands east of the Jordan River, an escarpment overlooking the rift valley, have an average elevation of 2,000–3,000 feet (600–900 m) and rise to about 5,755 feet (1,754 m) at Mount Ramm, Jordan’s highest point, in the south. Outcrops of sandstone, chalk, limestone, and flint extend to the extreme south, where igneous rocks predominate.

The Jordan Valley drops to an average of 1,312 feet (400 m) below sea level at the Dead Sea, the lowest natural point on the Earth’s surface.

The Jordan River, approximately 186 miles (300 km) in length, meanders south, draining the waters of Lake Tiberias (better known as the Sea of Galilee), the Yarmūk River, and the valley streams of both plateaus into the Dead Sea, which occupies the central area of the valley. The soil of its lower reaches is highly saline, and the shores of the Dead Sea consist of salt marshes inhospitable to vegetation. To its south, Wadi Al-‘Arabah (also called Wadi Al-Jayb), a completely desolate region, is thought to contain mineral resources.

In the northern uplands several valleys containing perennial streams run west. Around Al-Karak they flow west, east, and north. South of Al-Karak intermittent valley streams run east toward Al-Jafr Depression.

The country’s best soils are found in the Jordan Valley and in the area southeast of the Dead Sea. The topsoil in both regions consists of alluvium—deposited by the Jordan River and washed from the uplands, respectively—with the soil in the valley generally being deposited in fans spread over various grades of marl.

Jordan’s climate varies from Mediterranean in the west to desert in the east and south, but the land is generally arid. The proximity of the Mediterranean Sea is the major influence on climates, although continental air masses and elevation also modify it. Average monthly temperatures at Amman in the north range from the mid-40s to the high 70s °F (low 10s to mid-20s °C), while at Al-‘Aqabah in the far south they range from the low 60s to the low 90s °F (mid-10s to low 30s °C). The prevailing winds throughout the country are westerly to southwesterly, but spells of hot, dry, dusty winds blowing from the southeast off the Arabian Peninsula frequently occur and bring the country its most uncomfortable weather. Known locally as the khamsin, these winds blow most often in the early and late summer and can last for several days at a time before terminating abruptly as the wind direction changes and much cooler air follows.

Precipitation occurs in the short, cool winters, decreasing from 16 inches (400 mm) annually in the northwest near the Jordan River to less than 4 inches (100 mm) in the south. In the uplands east of the Jordan River, the annual total is about 14 inches (355 mm). The valley itself has a yearly average of 8 inches (200 mm), and the desert regions receive one-fourth of that. Occasional snow and frost occur in the uplands but are rare in the rift valley. As the population increases, water shortages in the major towns are becoming one of Jordan’s crucial problems.

The flora of Jordan falls into three distinct types: Mediterranean, steppe (treeless plains), and desert. In the uplands the Mediterranean type predominates with scrubby, dense bushes and small trees, while in the drier steppe region to the east species of the genus Artemisia (wormwood) are most frequent. Grasses are the prevalent vegetation on the steppe, but isolated trees and shrubs, such as lotus fruit and the Mount Atlas pistachio, also occur. In the desert, vegetation grows meagrely in depressions and on the sides and floors of the valleys after the scant winter rains.

Only a tiny portion of Jordan’s area is forested, most of it occurring in the rocky highlands. These forests have survived the depredations of villagers and nomads alike. The Jordanian government promotes reforestation by providing free seedlings to farmers. In the higher regions of the uplands, the predominant types of trees are the Aleppo oak (Quercus infectoria Olivier), the kermes oak (Quercus coccinea), the Palestinian pistachio (Pistacia palaestina), the Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis), and the eastern strawberry tree (Arbutus andrachne). Wild olives also are found there, and the Phoenician juniper (Juniperus phoenicea L.) occurs in the regions with lower precipitation levels. The national flower is the black iris (Iris nigricans).

The varied wildlife includes wild boars, ibex, and a species of wild goat found in the gorges and in the ‘Ayn al-Azraq oasis. Hares, jackals, foxes, wildcats, hyenas, wolves, gazelles, blind mole rats, mongooses, and a few leopards also inhabit the area. Centipedes, scorpions, and various types of lizards are found as well. Birds include the golden eagle and the vulture, while wild fowl include the pigeon and the partridge.

The overwhelming majority of the people are Arabs, principally Jordanians and Palestinians. There is also a significant minority of Bedouin, who were by far the largest indigenous group before the influx of Palestinians following the Arab-Israeli wars of 1948–49 and 1967. Jordanians of Bedouin heritage remain committed to the Hāshimite regime, which has ruled the country since 1923, in spite of having become a minority there. Although the Palestinian population is often critical of the monarchy, Jordan is the only Arab country to grant wide-scale citizenship to Palestinian refugees. Other minorities include a number of Iraqis who fled to Jordan as a result of the Persian Gulf War and Iraq War. There are also smaller Circassian (known locally as Cherkess or Jarkas) and Armenian communities. A small number of Turkmen (who speak either an ancient form of the Turkmen language or the Azeri language) also reside in Jordan.

The indigenous Arabs, whether Muslim or Christian, used to trace their ancestry from the northern Arabian Qaysī (Ma‘ddī, Nizārī, ‘Adnānī, or Ismā‘īlī) tribes or from the southern Arabian Yamanī (Banū Kalb or Qaḥṭānī) groups. Only a few tribes and towns have continued to observe this Qaysī-Yamanī division—a pre-Islamic split that was once an important, although broad, source of social identity as well as a point of social friction and conflict.

Nearly all the people speak Arabic, the country’s official language. There are various dialects spoken, with local inflections and accents, but these are mutually intelligible and similar to the type of Levantine Arabic spoken in parts of Palestine, Lebanon, and Syria. There is, as in all parts of the Arab world, a significant difference between the written language—known as Modern Standard Arabic—and the colloquial, spoken form. The former is similar to Classical Arabic and is taught in school. Most Circassians have adopted Arabic in daily life, though some continue to speak Adyghe (one of the Caucasian languages). Armenian is also spoken in pockets, but bilingualism or outright assimilation to the Arabic language is common among all minorities.

Virtually the entire population is Sunni Muslim. Christians constitute most of the rest, of whom two-thirds adhere to the Greek Orthodox Church. Other Christian groups include the Greek Catholics, also called the Melchites, or Catholics of the Byzantine rite, who recognize the supremacy of the Roman pope; the Roman Catholic community, headed by a pope-appointed patriarch; and the small Syrian Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch, or Syrian Jacobite Church, whose members use Syriac in their liturgy. Most non-Arab Christians are Armenians, and the majority belong to the Gregorian, or Armenian, Orthodox church, while the rest attend the Armenian Catholic Church. There are several Protestant denominations representing communities whose converts came almost entirely from other Christian sects.

The Druze, an offshoot of the Ismā‘īlī Shī‘ite sect, number a few hundred and reside in and around Amman. About 1,000 Bahā’ī—who in the 19th century also split off from Shī‘ite Islam—live in Al-‘Adasiyyah in the Jordan Valley. The Armenians, Druze, and Bahā’ī are both religious and ethnic communities. The Circassians are mostly Sunni, and they, along with the closely related Chechens (Shīshān)—a Shī‘ite group, numbering about 1,000, who are descendants of 19th-century immigrants from the Caucasus Mountains—make up the most important non-Arab minority.

The landscape falls into two regions—the desert zone and the cultivated zone—each of which is associated with its own mode of living. The tent-dwelling nomads (Bedouin, or Badū), who make up some one-tenth of the population, generally inhabit the desert, some areas of the steppe, and the uplands. The tent-dwelling Bedouin people have decreased in number because the government has successfully enforced their permanent settlement. Urban residents who trace their roots to the Bedouin make up more than one-third of Jordanians.

The eastern Bedouin are principally camel breeders and herders, while the western Bedouin herd sheep and goats. There are some seminomads, in whom the modes of life of the desert and the cultivated zones merge. These people adopt a nomadic existence during part of the year but return to their lands and homes in time to practice agriculture. The two largest nomadic groups of Jordan are the Banū (Banī) Ṣakhr and Banū al-Ḥuwayṭāt. The grazing grounds of both are entirely within Jordan, as is the case with the smaller tribe of Sirḥān. There are numerous lesser groups, such as the Banū Ḥasan and Banū Khālid as well as the Hawazim, ‘Aṭiyyah, and Sharafāt. These traditionally paid protection money to larger groups. The Ruwālah (Rwala) tribe, which is not indigenous, passes through Jordan in its yearly migration from Syria to Saudi Arabia.

Rural residents, including small numbers of Bedouin, constitute about one-sixth of the population. The average village contains a cluster of houses and other buildings, including an elementary school and a mosque, with pasturage on the outskirts. A medical dispensary and a post office may be found in the larger villages, together with a general store and a small café, whose owners are usually part-time farmers. Kinship relationships are patriarchal, while extended-family ties govern social relationships and tribal organization.

Roman theatre ruins (foreground), surrounded by the city of Amman, Jordan. Ara Guler, Istanbul

More than four-fifths of all Jordanians live in urban areas. The main population centres are Amman, Al-Zarqā’, Irbid, and Al-Ruṣayfah. Many of the smaller towns have only a few thousand inhabitants. Most towns have hospitals, banks, government and private schools, mosques, churches, libraries, and entertainment facilities, and some have institutions of higher learning and newspapers. Amman and Al-Zarqā’, and to some extent Irbid, have more modern urban characteristics than do the smaller towns.

The population of Jordan is predominantly young. Persons younger than age 15 constitute almost two-fifths of the population, and some two-thirds of the population is younger than age 30. The birth rate is high, and the country’s population growth rate is about double the world average. The average life expectancy is also higher than the world average. Internal migration from rural to urban centres has added a burden to the economy, however, many Jordanians live and work abroad.

Some one-third of Jordan’s population are Palestinians. The influx of Palestinian refugees not only altered Jordan’s demographic map but has also affected its political, social, and economic life. Jordan’s population in the late 1940s was between 200,000 and 250,000. After the 1948–49 Arab-Israeli war and the annexation of the West Bank, Jordanian citizenship was granted to some 400,000 Palestinians who were residents of and remained in the West Bank and to about half a million refugees from the new Israeli state. Many refugees settled east of the Jordan River. Between 1949 and 1967, Palestinians continued to move east in large numbers. After the 1967 war, an estimated 310,000 to 350,000 Palestinians, mostly from the West Bank, sought refuge in Jordan. Thereafter immigration from the West Bank continued at a lower rate. During the Persian Gulf War (1990–91), some 300,000 additional Palestinians fled (or were expelled) from Kuwait to Jordan, and as many as 1.7 million Iraqis flooded into the kingdom during the war and the years that followed. Another smaller wave arrived in 2003 after the start of the Iraq War. Most of these Iraqis left, but perhaps 200,000 to 300,000 remain. Only a small fraction are registered as refugees.

Most Palestinians are employed and hold full Jordanian citizenship. By the early 21st century, approximately 1.6 million Palestinians were registered with the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), an organization providing education, medical care, relief assistance, and social services. About one-sixth of these refugees lived in camps in Jordan.