Figure 1.1 The walled garden model, regulated by the three-degrees structure.

Through the Yamauchi and Iwata eras, the lesson has always been the same. It is a simple lesson, but it is something so many video game designers, publishers and hardware manufacturers have missed or messed up. It is a lesson that will always be the Nintendo motto.

Never relinquish control. (Stuart 2015)

When we think of video games, we usually think of a combination of hardware and software: first we buy a system, and that system is used to play a number of different games. Everything we buy as end users is the result of a five-stage process: development, publishing, manufacturing, distribution, and retail (Williams 2002, 46). Software developers and publishers work together with hardware manufacturers to create a sustainable product ecosystem and market, if not without some disturbances. In 2010, industry analyst Nicholas Lovell described the typical business model of console manufacturers:

The current generation of consoles is predicated on companies subsidizing a very expensive piece of hardware, and recovering their money mainly through a tax on everyone who wants to develop games for their platform. You can make some money selling consoles at the end of their lifecycle, after all the research and development is paid off, but the core of the model is that the console manufacturers have absolute control over their platforms and over who gets to develop games for them. (Lovell cited in Chatfield 2010, 215–216)

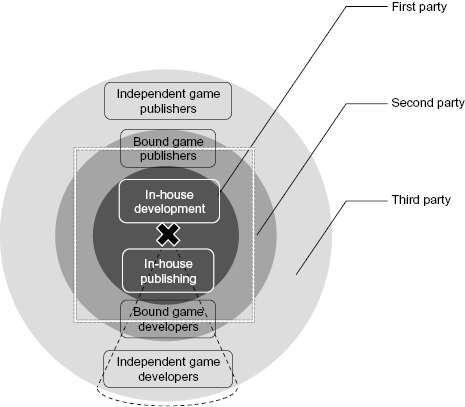

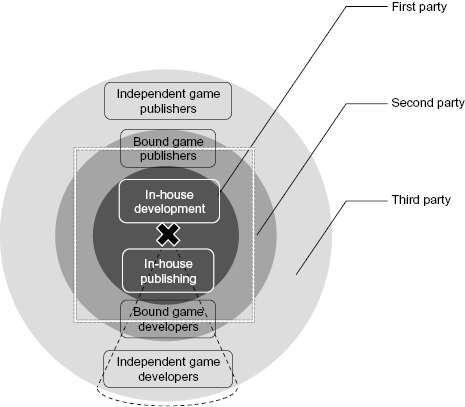

This is what Chatfield describes as the “walled garden” model, which traditionally characterizes the video game industry and relies on three conceptual entities. The first-party firm typically is the console manufacturer (or platform provider), who usually doubles as a game publisher and often triples as a game developer. Developers are responsible for producing a game’s code and contents in a timely fashion while respecting the allotted budget. The budget for developing the game, marketing, distribution, rights and licensing management, sales, and all financial aspects of the games business is handled by publishers. Third-party licensees are external firms that develop or publish games for the first party’s platform. Last, although the “second party” term traditionally refers to the consumer buying the good from the first party, in the video game industry, the word covers the myriad possibilities for hybrid ownership status that results in an external firm having closer ties with the first party than other “regular” third-party licensees. Such cases include independent developers contractually bound to develop games exclusively for a publisher or platform owner, or developers where a significant stake is owned by them. For this reason, it makes sense to think of the parties as positioned over three degrees of distance from the epicenter that the platform constitutes, as illustrated in figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 The walled garden model, regulated by the three-degrees structure.

In the figure, “X marks the spot” (the platform), and a square wall is erected outside the first-party internal development studios and publishing divisions. This wall passes right through the second-party publishers and developers, who are contractually bound to the platform owner and yet still have one foot outside the garden. Third-party publishers and developers are sitting outside and are only authorized access under the platform owner’s conditions, whose gatekeeping efforts rely on licensing agreements with second- or third-party publishers or on a publishing agreement between the platform owner’s in-house publishing and second- or third-party game developers (who are cast in its net, represented by the dashed cone).

The “walled garden” and the three-party structure of the industry, with associated developers, publishers, and platform providers, has become so deeply ingrained in our minds that it may appear to be the only business model that allows a platform to thrive. But that was not always the case. This model had to be developed; it is not a default state of things. Moreover, it does not aptly represent Nintendo’s business model, which I term a self-party firm. This chapter introduces a vocabulary and concepts from business studies to chronicle the development of Nintendo’s business model, situating it in a marketing history of home video games.

Most studies conducted on the home video game market, management, and business treat it as a standard-based industry (Kline, Dyer-Witheford and de Peuter 2003, 110–112; Williams 2002; Schilling 2002), where firms (game developers) must develop products (games) according to the compatibility requirements of a certain standard (a console) over another. This approach is necessary because standards are lowering the investment necessary for game developers to make their products available to their consumers; without standards, developers would have to constantly reinvent (and remarket) the wheel, so to speak. This valuable lesson was learned from the first generation of dedicated home video game consoles (1972–1977), where every game developer manufactured its own machines. It also forced consumers to buy and replace or stockpile systems at home, perhaps successively investing in Coleco’s Telstar Classic, Telstar Ranger, Telstar Combat!, and a dozen others. It quickly made more sense to ask the consumer to pay a relatively important fee to gain access to the standard (thanks to a “compatible player,” a console) to buy individual titles cheaply afterward in cartridge form, just as with record players or VHS systems.

This move made video games a two-sided market. Some firms develop and sell hardware (consoles, the base good), which make up the first side of the market, whereas other firms develop and sell software (games, the complementary goods) for the second side. Some firms such as Nintendo, of course, cater to both sides of the market. The goals, motives, and obstacles for each of these sides—hardware and software—are not always convergent and can sometimes be at odds. A platform owner wants its platform to be the most successful on the market so that ideally all consumers want to buy it, and the platform’s price should be high enough to bring in profit. A game publisher may prefer the industry to have a healthy number of platforms (so that their games do not depend on an all-powerful platform owner who holds the key to the market’s one gate), and the platform’s price should be low enough to bring in the most consumers with extra cash to spend on games.

Standard-based industries are particularly competitive in nature because their theoretically large market is effectively divided among the various standards, each of them holding a market share; if you’re making a Super NES game, it doesn’t matter that the global, total video game business is $4 billion big—if the SNES has a 40% share of the home console market, then that’s your effective market size. This makes the home video game market hypercompetitive: “competition has flourished as each firm sought (and seeks) the greatest network externalities arising from the largest user base. Without interoperability, it is difficult for firms to see each other as anything besides a threat to their user base” (Williams 2002, 43).

Obviously, barring other strategic factors, firms that produce games will prefer producing their goods for the standard that has seen the widest adoption among consumers (measured as the installed base, i.e., the number of machines that have been sold to consumers and are currently active) to maximize their sales potential. As Gallagher and Park note, “strategy concepts that center around developing market share and mass acceptance of products, such as economies of scale, first mover advantage, and technological innovation, feature greater prominence in the analysis of these [standard-based] industries than they do for others.” (Gallagher and Park 2002, 67)

Paradoxically, although conquering market share is the games industry’s ever-pressing goal, the industry’s conditions preclude firms from developing long-term strategic planning, the usual route that leads to the capture of market share. Kline, Dyer-Witheford, and de Peuter noted this problem in Digital Play (2003, 76–77) and offered that the games industry does not proceed through carefully orchestrated plans and a strategic management of innovation insomuch as it is “riding chaos” due to the constant promises of new technology. As Shankar and Bayus write, the 16-bit generation’s “console war” did not differ: “The business strategies of Nintendo and Sega centered on their hardware systems, and these firms did not exhibit long-term strategic pricing or advertising behavior.” (Shankar and Bayus 2003, 377) These factors may explain the particularly volatile nature of the games industry, which is considered a boom-or-bust, winner-take-all market (Schilling 2002, Grant 2002).

In standard-based industries, market share is a valuable strategic resource in itself, instead of being only a consequence of the firm exploiting its strategic resources to sell its products. Firms expend great effort in building market share because a standard’s value is derived directly from its adoption rate. Moreover, market share is traditionally seen as a zero-sum game played out between competing standard bearers. This is why the video game industry typically measures a game console’s success by its market share. As a zero-sum game, it means that every gain one firm makes is at the expense of the others. If a gamer that owns an Xbox One decides to spend $400 to buy a PlayStation 4, then that’s $400 less for spending on Xbox One games. Hence, standards tend to entrench consumers through an effect known as lock-in; after spending $400 on an Xbox One, a gamer is likely to see the need to recoup the hardware’s cost by buying games for the system.

Because an initial investment is required to gain access to the standard, changing standards would require consumers to buy another machine, hence creating important switching costs for them (Katz and Shapiro 1985, Gallagher and Park 2002). Hence, consumers will be reluctant to spend their money up front to gain access to a standard that may not be properly supported—no one wants to be stuck with a machine for a failed standard. This situation is treated in business studies and economics as either the technology adoption problem or the standards race (Schilling 1999, Gallagher and Park 2002), with complex strategies favoring the spread of new technologies among consumers. It is a crucial part of the life of platforms, and I’ll cover it extensively in chapter 2.

When all goes well for a new video game console, a core audience of enthusiasts becomes early adopters, some good games are released, and a bandwagon effect takes place as more people adopt the technology and more developers make games. This leads to network effects (or network externalities), a term that identifies the positive effect that owning a good can bring to other users of the same good, either directly or indirectly, as Clements and Ohashi explain:

Many high-tech products exhibit network effects, wherein the value of the product to an individual increases with the total number of users. Often these effects operate indirectly through the market for a complementary good. For example, the value of a CD player depends on the variety of CDs available, and this variety increases as the total number of owners of CD players increases. […] we explicitly characterize the indirect network effect as an interaction between console purchases made by consumers and software supply chosen by game providers. (Clements and Ohashi 2005, 515–516)

Therefore, platform owners will seek to maximize their network because the more users adopt their platform, the more game developers and publishers are going to consider it. In addition, Shankar and Bayus (2003) identified a self-reinforcing dynamic at work when a large network is in place: a number of impromptu consumer-led promotional and circulation practices, such as word-of-mouth discussions and the borrowing and swapping of games. Thanks to the networked play practices of kids who played together and borrowed and exchanged games in the NES era, the games’ high cost could be mitigated as each friend contributed his own small library of games to the common pool, reinforcing the network effect through a horizontal consumer-to-consumer axis (or, in other words, a “peer pressure” effect). These kinds of informal networks between peers are seldom discussed but are particularly influential when the main target demographic is composed of children.

On the larger scale of the platform as a whole, new console owners in the home video game market do not typically result in immediate benefits to other console owners.1 In this situation, the network effects are of the indirect variety: customers buy the console, augmenting its adoption rate, which will hopefully influence game developers to adopt the standard as well and make games for it, which customers will buy, thereby generating revenue for the game’s developer and publisher and for the platform owner. This creates a virtuous cycle (or, in cybernetic terms, a positive feedback loop—the changes from the initial state spur further changes in a self-reinforcing effect) of increasing desirability for the platform in both consumers’ and game publishers’ minds. The whole enterprise hinges on a single common, all-encompassing factor: confidence, from game developers and gamers alike. In this sense, video game platform owners are juggling two businesses at once: conducting business-to-business (B2B) operations with game developers and publishers and business-to-consumer (B2C) sales of consoles and customer support.

This description of the home video game market can be imperfectly applied to describe in general terms a wide range of game consoles thanks to a shared vocabulary. But each platform owner and console must be analyzed to identify its particularities. In the rest of this chapter, I will present the economic models of both Atari and Nintendo, and question some of the basic tenets of video game marketing in the process to refine our understanding of platforms as marketing entities and their impact on the video game business.

As we saw earlier, the biggest hurdle in achieving platform success is the technology adoption problem. In standard-based industries, gaining market share and a larger installed base is the one condition to building confidence among consumers and producers of complementary goods as well, which are the cornerstones of an expansive standard ecosystem. When Microsoft entered the home video game market in 2001, they were losing more than $100 on every Xbox sold to consumers (Takahashi 2011). This amount was dwarfed by Sony’s PlayStation3, whose sales cost Sony between $240 and $300 per machine, depending on hardware configuration (Bangeman 2006). The lesson? Building market share is something to be done at any cost.

The adoption of a standard can be stimulated by this well-known, often-mentioned, but ultimately seldom-discussed strategy: “giving away the razors in order to sell the blades” (Kline, Dyer-Witheford, and de Peuter 2003, 112–113). Although conventional wisdom usually describes the video game market in these terms, the so-called “Gillette model” and razor-and-blades analogy need some thorough recontextualization. The general idea is a sound strategy in economics: sacrifice short-term profit by subsidizing the base good in order to build the largest possible installed base and recoup the losses with the sale of complementary goods over time. However, things are not that simple, as Picker (2010) notes by resorting to video game consoles as an example, because the strategy depends on the firm’s ability to lock in the consumer:

You can’t lock in anyone with a free razor if someone else can give them another free razor. Indeed, all of this suggests just the opposite: if you want to create switching costs through the razor, the razor needs to have a high price, not a low one. […] Think of switching from the Xbox to the PlayStation III. In contrast, users of free razors face zero switching costs if the alternative is another free razor. (Picker 2010, 2)

Gillette’s razor system was patented in 1904 and thus protected until 1921; during that first period, the cost of a Gillette razor was, in fact, high. Only when the patent expired and competitors started issuing their own cheaper razors and blades did Gillette switch strategies to underprice and effectively subsidize the first stage of the market (the sale of the razor) with a relative overpricing of the second stage (the sale of the disposable blades). In the video game industry, platforms are walled in by the relatively high cost of consoles, which serves as an incentive for consumers to develop loyalty toward the platform they have chosen because they are also investing in it. But platform owners, even when selling consoles at high prices, will forego profit or even incur losses in selling them. This strategy relies on another crucial point of control (over the aftermarket of complementary goods, games) that is often passed over:

If the razors are actually being sold at a loss—given away for free—then a better strategy seems clear: let the other guy sell the razors at a loss while you sell only the profitable blades. […] That suggests that low-prices for razors only make sense if customers are loyal or if the razor producer can block other firms from entering the blade market. (Picker 2010, 2)

The modern video game market has, of course, integrated this lesson by erecting a second, legal wall around the platform gardens: that of licensing agreements. But things were not always so. One of the best lessons we can take away from the Gillette model is that pricing and licensing conditions in two-sided markets are not simple, and the dynamics of platform control and openness require delicate compromises and complex models that evolve through a platform’s lifecycle—and an industry’s history.

From their appearance in the arcade business, video games were rather conceived as game machines, like their pinball predecessors. Atari’s main line of business was the manufacturing of game machines, for arcades at first and then for the home. When Atari released its Home Pong in December 1975, its conception of what home video games should be was in line with the model of board games. When Parker Brothers sells a copy of Monopoly, it sells some hardware (a board, pieces, cards, and paper money) for a predestined activity (the game of Monopoly, whose rules are printed and included in the boxed goods); if people want to play Battleship, then they buy a copy of the Battleship game from Milton Bradley instead. The first home video game consoles were likewise dedicated to playing a single game.

This model framed home video games as a perpetual innovation market, where the sustainability of a game-producing firm depends on the continuous creation of new games sold separately, each of them competing against all other games available to a given consumer. Whereas some industries can resort to planned product obsolescence (the nylon stocking and electric lightbulb are quintessential examples) or rely on service, maintenance, replacement parts, or consumables to ensure a certain amount of repeat business and a steady cash-flow to the firm, this is not the case here. In perpetual innovation markets, a firm must constantly create new, desirable products. As competing manufacturers developed and sold their own electronic ping-pong game systems for the home, Atari sought to maintain its lead through constant product innovation, something its founder Nolan Bushnell disturbingly called “eating his own babies,” to keep his company ahead of the “jackals,” the competing firms feeding on the carcasses of Atari’s innovative products by copying them. (Kent 2001)

Although constantly developing new products was working well in the video arcade market, the home market required some means for providing a number of games to people without them having to fill their garages or closets with out-of-flavor (and expensive) machines. The solution came through the development of a game console that would use interchangeable cartridges of Read-Only Memory (ROM), on which programs could be stored and marketed separately. This marked the shift toward home video games as a standard-based industry. As Atari was working on this project (codenamed “Stella”) in November 1976, Fairchild Semiconductor released its Video Entertainment System (VES) machine, offering exactly what Atari wanted to. This release forced Atari to move faster and finish Stella before Fairchild could completely corner the market. Atari rushed and in September 1977 released its Video Computer System (VCS), a name chosen to compete directly with the VES. Eventually, both consoles would be renamed the Fairchild Channel F and the Atari 2600, respectively, the latter reigning unchallenged over the home video game market after Fairchild abandoned it.

Because the 2600 featured interchangeable game cartridges, it was a first step toward the idea of a two-stage, two-sided market that would eventually become the dominant structure in contemporary home video games. Fairchild’s VES was priced at $169.95 for the console and $19.95 for cartridges, whereas the VCS retailed for $199.95 and between $19.95 and $39.95 for the games (Schilling 2006, 77; also visible in Atari Age magazine’s regular mail-order pages). Analysts were quick to describe Atari’s and Fairchild’s businesses as a transposition of the razor-and-blades model, assuming the firms were selling base durable goods at a low profit margin, so that consumers would then be locked into the long-term purchase of complementary, consumable goods sold at a high profit margin.

It turns out that analysts were too quick in making that judgment. In fact, Atari was slow in embracing that model, and initially remained very much a hardware business of selling game machines. The Atari 2600 had been meant to last 3 years, from 1977 to 1979, and its primary goal was to allow consumers to play arcade games at home (DeCuir 1999, 5). The plan was to have consumers upgrade to the next Atari system afterward; research and development efforts went into the post-2600 future (the eventual Atari 5200, 400 and 800) as soon as the 2600 was released. Bushnell’s philosophy of “eating your own babies” meant he didn’t want Atari to rest on the 2600’s market success. Simply put, Atari never gave its razors away by selling them for just enough to break even while hoping to eventually profit from games after building up a large installed base; it simply sold game hardware for profit and then had an even bigger profit margin from its game software. The longevity of the second-stage software cartridges aftermarket was not strategically planned ahead from the beginning.

An article from InfoWorld in 1983 debunked the already prevalent myth of the razor-and-blades model:

Industry wisdom has always had it that Atari never made money on the video computer system – it was supposed to be the razor that’s all but given away so people will buy razor blades. In fact, it costs about $40 to manufacture a VCS. The average selling price last year [1982] was $125. (Hubner and Kistner 1983, 152)

Although it looks good on paper, the manufacturing cost of $40 per unit took a long time and significant effort to achieve: namely, expanding mass production with larger orders, redesigning the casing and materials for efficiency gains, and offshoring manufacturing to Hong Kong were all specific efforts that added up. But the main natural factor at work is the fact that technology costs tend to go down rapidly in a few years when dealing with computer hardware. The remarkable profit margin from Atari’s 2600 hardware is a result of the lack of serious competition it faced from rivals. Without such an incentive, Atari maintained a healthy profit margin on hardware.

In the end, although Atari made great money selling its blades, it never stopped making money selling its razors. One indication that the firm was still attached to hardware sales can be found in the (ultimately misguided) decision to overproduce millions of copies of Pac-Man, in the hope the game would sell more systems (Barton and Loguidice 2008, 5). One crucial point to keep in mind, then, is that Atari struggled and attempted mixing strategies to adapt its practices as it went along. On the one hand, it wanted to profit from the gold mine that was the second stage of the 2600 market; on the other hand, it remained conscious of the need to plan the next, more advanced market to follow and not to cave itself in the current market and the 2600’s game library. Because the software side of the market proved so much more profitable than the hardware side, however, Atari management shifted the firm’s weight increasingly toward the maximization of production and sale of cartridges for the 2600. (Covert 1983, 60)

The need to control the lucrative aftermarket hit Atari hard in 1981, when some of their best programmers quit to produce 2600 games on their own, forming the independent game publisher Activision. Atari first tried to sue them, but without a technological or legal way to lock the team of rogue programmers out of the 2600 games market, Atari changed strategies, settling on, “If you can’t beat them, have them join you instead.” Atari signed a royalties agreement with Activision to get a part of their blades’ profits, tapping into an unanticipated third revenue stream: third-party publisher royalties. Activision’s games could also help Atari sell more razors, enlarging the 2600’s installed base and opening the possibility for more game sales.

Following the logic of “more is more,” Atari welcomed all kinds of new third-party publishers and signed royalties agreements with them (Barton and Loguidice 2008, 4). The matter now was not to lock competing firms out of its platform, as with Activision at first, but instead to lock them in and ensure they developed games for the 2600 and not for the systems of rivals Mattel or Coleco. The Atari garden had to be the most expansive and lush, with variegated foliage spewing colors in all directions. Diversity of products came from amateur software firms that developed games with candid enthusiasm.

Atari’s new business model capitalized on three revenue streams. The first side of the market, hardware, accommodated an elastic profit margin, as high as consumer demand, competition from rivals, and price of components, assembly, distribution, and retailers’ cut permitted. That uncertain profit margin was secondary, behind the high profit margin on Atari’s cartridge software sales that made up the bulk of the market’s second side. A modest royalty fee collected from third-party game publishers complemented software-side revenue. Although the direct amounts were modest, these third-party games played an important role in increasing the software offer for consumers, hence platform desirability, which in turn led Atari to sell more hardware and possibly more of its games.

The economic model’s throwaway attitude toward third-party products had important ramifications on the kinds of games developed and sold for the platform. Anyone could hire an ex-Atari programmer (or poach one away) and have him or her single-handedly develop a game, no matter how novel (or bad) of an idea it was. This comparatively low barrier to entry encouraged the proliferation of software and constitutes a creative affordance for game developers who used the platform—arguably, the first affordance (quite literally) that came before any technology or design considerations, which made them able to afford developing and publishing a game for the console.

This economic model was not without faults, however. Two crucial elements were missing from its foundations, both demonstrated by Atari’s Pac-Man and E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial debacles. The first is software quality. An increase in software offer may not translate into increased console desirability if the software is not interesting to consumers. This realization came down hard—but too late—on Atari when shoddy game titles started selling at bargain-bin prices in an attempt to (minimally) recoup the investments of second-rate game development companies that had jumped in the market in a “gold rush” effect. This is because Atari did not create sufficient barriers to entry. The various policies and regulations that platform owners impose on software developers wishing to use their platforms, as well as the financial and logistical conditions required to meet the minimum operating criteria required (teams of employees, office space, equipment, software licenses, etc.), taken as a whole, act as a gating mechanism to protect a market from free-for-all competition. With sufficient barriers to entry, only firms that can successfully overcome the barriers can produce games for the standard and compete in this market.

The second factor missing from Atari’s model was software quantity and the resulting peril of market saturation. When most homes likely to buy a 2600 have already done so, the extra desirability conferred to the platform by the third-party games is no longer translating into hardware sales and consequent profits to Atari. Instead, games from third-party publishers are simply cannibalizing Atari’s main revenue stream from game sales because the royalty Atari collects from third-party games is significantly less than the profit it makes from selling its own first-party games.

These factors took the Atari Boom to the inevitable next phase of an industry characterized by boom-and-bust cycles: the Atari Bust. Because Atari’s competitors Mattel and Coleco had both developed an adapter to play 2600 games on their own consoles, the shared standard’s failure brought them down in the spiral as well. The Atari Bust became the North American Video Game Crash. Record losses were posted, firms closed, retailers cleared inventories and saved shelf space for other products, and newspaper titles claimed that video games were dead. Fire and brimstone everywhere.

And then came Nintendo with the NES in 1985.

Lo and behold! The world of games was enshrouded in darkness, and Nintendo alone was holding the flame. Or so a common discourse, found in both business-oriented histories and fanboy comments, would have it. Tristan Donovan deftly summarizes the usual position:

Nintendo’s success reconfigured the games industry on a global level. It brought consoles back from the dead with its licensee model, which became the business blueprint for every subsequent console system. It revitalised the US games industry, turning it from a $100 million business in 1986 to a $4 billion one in 1991. Nintendo’s zero tolerance of bugs forced major improvements in quality and professionalism, while its content restrictions discouraged the development of violent or controversial games. (Donovan 2010, 177)

Key to Nintendo’s approach was a second NES—behind, yet before the Nintendo Entertainment System, laid a Nintendo Economic System. On the surface of business-to-consumer politics, Nintendo presented itself as a family-friendly entertainment provider, a gateway to worlds of imagination that children could safely enter without fearing inappropriate contents—a discourse meant, of course, to reassure parents, the ones with disposable income to buy the NES and games for their children. But this safety net hinged on tight control over the video games produced by third-party developers and publishers. Thus, at the core of business-to-business marketing, Nintendo was an autocratic conqueror who did everything in its economic and legal power to control the chaotic multitude that characterized the video game industry. To be an external game developer or publisher at the time of the NES meant putting up with unprecedented conditions as a software CEO at the time explained:

We come up with an idea and submit it to Nintendo. Months later, they’ll say yea or nay. If it’s a go, we spend months and money writing the program. We then send in the final version. Again, they review it. If they decide they don’t like it, everything we have done is wasted. If they decide it is only so-so, they will make only a few cartridges and we make no money. We have no say. We are at their mercy. They can make or break any of us overnight. (Palmer 1989, 20)

Just how did Nintendo achieve the position of strength necessary to impose such draconic measures to business partners? They did it by staying true to a central principle, aptly worded by Keith Stuart (2015): “Never relinquish control.”

The NES story begins in Japan in 1983, a world very different from the bust cycle the American market was entering (and known in Japan as the “Atari Shock”). Florent Gorges deflates the somewhat overblown importance of the Crash in United States–centric dominant video game history, noting that, “video arcades remained intensely busy” all around the world, Europe was seeing multiple manufacturers developing “inexpensive micro-computers,” and Japan was rather entering a boom cycle: “The console market even hits record activity in the land of the rising sun! Between 1982 and 1983, no less than ten machines are launched to conquer a bustling industry!” (Gorges 2011, 47; freely translated)

In July 1983, Nintendo released its Famicom (Family Computer) console on the Japanese market with a peculiar business model. Nintendo’s history as a toy manufacturer, coupled with its experience with the portable electronic Game and Watch devices (chronicled in Gorges 2010) and the phenomenal distribution and retail networks it had developed (explained later in chapter 6), had convinced the firm it had all that was needed to design, launch, and maintain both the Famicom and its software. It went on sale at the incredibly low price point of 14,800 yen (around $60)—half the price of the competition. How could such a low price be attained?

First, there is the usual technocommercial explanation that Nintendo adopted its engineer Gunpei Yokoi’s philosophy of “lateral thinking with seasoned (or withered) technology.” Nintendo’s Masayuki Uemura implemented a custom software architecture and custom chips to keep the console focused on some key performance issues (great graphical quality at a low manufacturing cost), and Nintendo shopped around for a long time looking for a semiconductor manufacturer willing to supply them with the right processor at a low enough cost. They finally found a willing partner in Ricoh. Nintendo president Hiroshi Yamauchi bet the bank by placing an extremely high (and risky) order, which convinced Ricoh to agree on a very low price per unit thanks to this unprecedented volume.2

Although the technocommercial explanation works well to explain the short-term success in developing the Famicom, there is a larger, more important explanation. As we have seen with Atari in the United States, so far in the home video game industry, a platform owner drew substantial revenue from selling the hardware it had designed and produced. The situation for home computers was even more skewed toward the hardware side because computers, in principle, were more open platforms than specialized game consoles. In both cases, hardware firms were concentrating their efforts on the hardware side, and other firms were specialized in the software aftermarket. Not so with Nintendo.

Nintendo adopted the Gillette model, minding the two caveats explained earlier. First, the base good, the Famicom, sold for a nontrivial amount, which created switching costs for the consumer to get locked in. An important detail to keep in mind is that even at this phenomenally low cost, the Famicom was not losing Nintendo any money; the firm was making little profit, but the system wasn’t subsidized to consumers by selling it below its cost. Second, Nintendo kept all other firms out of the lucrative games aftermarket, thanks to the technological wall of a complicated console architecture that required sustained high-level effort to overcome. They would be the only ones developing and selling Famicom games, which is where they would make the bulk of their money, crystallizing a “software orientation” that has stayed with the corporation ever since (Inoue 2010). This position was antithetical to the principle of a “computer,” as various software publishers reproached (Gorges 2011, 49). Still, from its 1983 launch to halfway through 1984, Nintendo produced its games and kept the Famicom gates closed.

However, as the Famicom’s success grew, Nintendo could not develop and publish games fast enough to accommodate consumer (and retailer) demand. A choice had to be made: would it hire game developers, expand and substantially grow, or open up its platform to partner firms instead? According to Florent Gorges, the decision to open up the platform to third-party publishers, instead of hiring and training new teams internally, was taken because the latter solution would have taken too much time to fill in the Famicom market’s gaps. Nintendo had to open up to other firms by necessity, not by choice. (Gorges 2011, 49)

Drafting licensing agreements for third-party publishers posed a formidable problem. Nintendo’s approach, contrary to Atari’s and computer manufacturers’, was predicated on making almost no money on the hardware to sell it as cheaply as possible; this move would increase installed base, which would then determine the revenue generated from software sales over the console’s lifetime. From this point of view, third-party titles could drive hardware sales and technology adoption by consumers, but this ultimately held limited interest because these sales of hardware were not, by themselves, generating much profit. As such, third-party games posed an important threat to Nintendo’s true bottom line, game software sales, as Yamauchi explained: “Letting other publishers profit from the Famicom market amounts to sawing off the branch on which Nintendo is sitting!” (Gorges 2011, 50; freely translated)

This statement and position further showcases the need to envision platform economics as dynamic processes that change and adapt over a console’s life cycle. The venerable Atari had only accepted third-party games after it had taken a considerable lead in the software side of the market. Opening up the platform before achieving such a lead would be self-defeating, and even more so in the Nintendo Economic System. The licensing fees were not just a way to make quick and easy extra income, as they had been for Atari; they had to cover Nintendo’s lost revenue because these other publishers’ games would cannibalize sales of its own titles.

In this respect, Nintendo is not a first-party platform provider but rather part of a slightly different category of firms that I propose to call self-party platform owners. Self-party firms follow different strategies and settle on different business models than the classic first-party firms because they are significantly invested in the two sides of the market (hardware and software). First-party firms typically rely on third-party firms to contribute software to the platform hardware and thus tend to view them as partners and cooperators because they don’t compete for the same side of the market. Here, I rely on Dikmen, Rhizlane, and Le Roy’s aggregated definition of cooperation between firms (2011, 3), which is characterized by two notions. First is reciprocity, which refers to strategies of cooperation and coordination rather than domination, power, and control, favoring the establishment of trust, mutual dependency, and reciprocity. Second is engagement, which can be described as the willingness of partners to expend efforts to make their relationship work, considered in light of long- rather than short-term gains.

A self-party firm, in contrast, does not view third-party game developers and publishers as cooperators because it rules over them with strategies of domination and control. Reciprocity is absent, power relations are one-sided, and dependency is not mutual because the platform owner is also present in the software side of the market and thus can fulfill the core needs of the hardware side by supplying high-quality games. The self-party firm needs the third-party licensees’ support to broaden its games library, but it maintains the attitude of domination and forces them into asymmetrical subservience to deny them any competitive advantage. Third-party licensees and the self-party firm, on the software side, are “coopetitors,” competitors with whom it is necessary or wise to cooperate for the time being to achieve some particular goal or as long as interests are compatible. In the “walled garden” analogy, they carefully screen developers and publishers massed around their doors and reluctantly open the gate to a select few visitors, confining them to “guests quarters” that are well away from the garden’s Tree of Life and Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. The self-party platform owner knows what’s good, and its word is law, its power supreme. External firms are to be kept on the fringes, outside the platform’s cooperative ecosystem.

When Nintendo of Japan first opened the doors to its garden, it admitted only big, sturdy, reliable firms: Hudson, Namco, Taito, Jaleco, Konami, Capcom, Irem, and Bandai. Nintendo let them publish up to five games per year, which had to be exclusive to the Famicom, reviewed by Nintendo, and free of excessive violence or sexually suggestive content. With minor variations, the licensees typically manufactured and distributed their own cartridges and paid Nintendo a (rather large) 20% royalty that amounted to approximately $6 per cartridge (Hill and Jones 2012, C166). The deal was costly and the conditions strict, but the Famicom’s phenomenally low price, combined with Nintendo’s strong Famicom games (notably Donkey Kong and Mario Bros.), had led to such high hardware adoption that the market was huge, making it worthwhile for these firms.

Even those strict conditions were too much control relinquished for Nintendo’s taste, once the market had a steady influx of quality games. The Famicom was their garden, and if anyone wanted to play on their lawn, then they had to agree to their terms, which on top of everything so far reduced the number of games per year to three and included full control over the manufacturing process:

Future licensees were required to submit all manufacturing orders for cartridges to Nintendo. Nintendo charged licensees $14 per cartridge [on top of the 20% licensing fee], required that they place a minimum order for 10,000 units (later the minimum order was raised to 30,000), and insisted on cash payment in full when the order was placed. […] The cartridges were estimated to cost Nintendo between $6 and $8 each. The licensees then picked up the cartridges from Nintendo’s loading dock and were responsible for distribution. (Hill and Jones 2012, C167)

This latter combination of restrictions placed high barriers to entry to software developers and publishers. Producing a game on the Famicom meant covering all normal game development expenses but also bringing to the table at least $600,000 ($14 for manufacturing + $6 for licensing per cartridge x 30,000 cartridges minimum order) upfront before the cartridges were manufactured, distributed, and (hopefully) sold. In stark contrast to Atari’s VCS model, this was no place for amateurs or risky, unproven game concepts. The rules for software third-party firms were inflexible; as Nintendo would say to consumers years later when marketing the Nintendo 64, “Get N or Get Out.” Years later, when European game developers and publishers unaware of the “Famicom Boom” in Japan were introduced to the terms of the Nintendo Economic System, they largely chose to Get Out (Ichbiah 2004 [1997], 50). However, before that came the international breakthrough for Nintendo, which successfully marketed its Famicom in the United States as the Nintendo Entertainment System and in the process kept adding more restrictions to its licensing model.

Marketing the NES required a different approach, business-wise, to marketing the Famicom. The operation would be taken in charge by Nintendo of America, a subsidiary created in 1980 to take care of arcade games. The first challenge was to convince retailers and consumers to adopt the platform and the business model of selling the system at low profit to benefit from game sales. That could be done initially with the strong library of games the Famicom enjoyed, but eventually more games would be needed, and ideally games that could be more culturally relevant to an American audience. Getting new third-party game developers or publishers was not a challenge; getting them to agree to the exacting terms of the Nintendo Economic System, however, would be. But if the NES succeeded in taking the market in phase 1, firms would line up at the garden’s doors and sign to anything for phase 2, so Nintendo first tackled the problem of retailers.

Nintendo of America had done everything right to seduce retailers into trying out its “Entertainment System” in 1985 and 1986, after the Crash of 1983. Unlike the old man’s proposal from The Legend of Zelda, their “money-making game” was a lot less risky (and, presumably, formulated in better grammatical form). A “Nintendo SWAT team” descended on New York retailers (the test market) to set up displays and windows and stock them with systems and games. Retailers would get these free for 90 days, after which they could give Nintendo its due money for their sales and return any unsold inventory to them. (Hill and Jones 2012, C167–C168) In effect, NOA shouldered all the risk. The NES sold progressively more units in subsequent test markets, ramping up to a nationwide release in 1986 and eventually becoming the hottest toy on the market.3

Then Nintendo started flexing its newfound leverage muscle. Using its outsider status, it refused to continue playing the retail game according to the rules of the toy industry. (Sheff 1993, 165–169) Reports indicated that “Nintendo threatened to either slow or cut off supplies to retailers who lowered the price of the game as little as 6 cents” (Seattle Times, 1991): “threatened” or gave veiled hints at massive shortages for the future because legally a supplier or manufacturer of goods cannot force a retailer to sell it at a certain price.

Nintendo’s overbearing, top-heavy control over retailers came through Nintendo of America’s system of “inventory management,” as described by its marketing vice-president Peter Main (in Sheff 1993, 165). NOA withheld stocks and always underdelivered on retailers’ demands, a feat possible only thanks to its exclusive control over the manufacturing process per licensing agreements with third-party game publishers. Incidentally, this also allowed NOA to undermanufacture its licensees’ games and avoid leftover games stuck in warehouses and on retailers’ shelves. This in turn avoided the risks of product dumping and games being sold at discounted prices, and it kept game valuation consistently high but of course sometimes created “severe shortages” (Brandenburger and Nalebuff 1997, 113). Retailers were not the only ones to suffer from this system.

The same cocktail of policies found in Japan kept American third-party developers in line and clearly infeodated, begrudging vassals of the Nintendo Empire. Nintendo rapidly developed a reputation for acting as a corporate bully with third-party developers. As Jeff Ryan puts it, “Nintendo was enormous, controlling about 85 percent of the video game marketplace. It raked in billions every year. And it used its heft to insert onerous clauses into business contracts no one with any choice would agree to” (Ryan 2012, 135). Third-party developers and publishers, echoing the Hungry Goriya from The Legend of Zelda, would go “Grumble, grumble …” and take the bait anyway. It would have made no sense to pass up, given Nintendo’s market share and the kind of sales their games could obtain, especially with Nintendo’s severe micromanaging of inventory:

Greg Fischbach, founder of Acclaim Entertainment, was one of Nintendo of America’s first licensees. He found that his company could sell out every game it produced. And he wasn’t alone. “Every company sold out every game no matter how good it was, no matter how well the company was managed,” he said. “Anyone with product was able to sell it.” (Wesley and Barczak 2010, 21)

Nintendo of America licensees had it even rougher than Nintendo of Japan’s second-wave partners. Licensees were limited to five games per year, and all games had to be exclusive to the NES for a period of 2 years. Games were subject to a thorough evaluation process by Nintendo, which controlled them for bugs and general quality, but also to strip any objectionable content from them (see chapter 6). All games were manufactured by Nintendo in the quantities it judged appropriate. Firms had to place an order for at least 30,000 copies and pay the manufacturing fee to Nintendo directly in cash and in advance. Nintendo of America would also handle the distribution of their games. The royalty fee consisted of 30% of the licensee’s revenue (Harris 2014, 69).

In addition to the iron terms of the license, Nintendo put an additional technological lock in the NES. Despite its architectural complexity, Nintendo’s Famicom in Japan had been cracked by unauthorized game developers, and pirate carts were circulating widely. Never one to relinquish control, Nintendo found a way: It designed a Checking Integrated Circuit (CIC), or lockout chip, that was inserted in the console and cartridges. On power-on, each would send a specific bit of code known as “10NES”; if the cartridge couldn’t supply that code (the “key”), then the console would reset and try again. (Altice 2015, 90–91) The “lock and key” mechanism cemented technologically the legal walls of the license: Unauthorized cartridges could not run on the hardware, so licensees had to leave all manufacturing under Nintendo’s control.

Due to “inventory management” practices, third-party licensees sometimes received only a fraction of the games they wanted manufactured (and for which they had paid upfront cash) and sometimes months later than intended. As Ed Logg put it when discussing his development of the Tetris cartridge for Tengen, “Nintendo the first year was jacking everyone around with ‘ROM shortages.’ Their contract was very one sided; you paid all the money up front, assume all risk, they tell you how many [cartridges] you’re gonna get.” (tsr c.2000) In fact, Nintendo was suspected (and accused in a lawsuit) of manipulating order quantities and chip allocations to privilege the manufacturing of cartridges for its own releases while curbing third-party publishers’ competing titles. (Kent 2001, 388–390)

Nintendo’s level of control over all the vertical stages of the industry was bordering on trust, a technical business term to describe near-monopoly power over a market, and typically anticompetitive business practices to maintain it. Firms stuck outside the garden would attempt to break down or scale the walls of technology by reverse-engineering or bypassing the lockout chip, resulting in lawsuits. Through the NES’s golden years (the 1987–1988 “Nintendo Mania”), Nintendo’s actions would get them into an investigation by the Federal Trade Commission for anticompetitive practices (Provenzo 1991, 24; Tomasson 1991; Weber 1992).

The five vertical stages of the video game industry identified by Dmitri Williams (2002, 46) were all heavily invested or supervised by the Japanese giant. Nintendo’s main activities resided in development and publishing; its licensing agreement with third-party developers made it the world’s exclusive manufacturer of cartridges; it was substantially involved in the Shoshinkai network of distribution in Japan4 and distributed licensees’ cartridges in America. Finally, it kept retailers in line through overbearing monitoring. The self-party model certainly led to impressive results, as The Economist described in 1990:

Since 1983 its [Nintendo’s] pre-tax profits have grown by 30% a year. For the year ending March 1991, Nintendo is expected to make Y110bn [110 billion yen] ($750m) before taxes on sales of Y420bn. It is now making as much money as Sony on a third of the turnover – a sure sign of its control over the market. (The Economist, August 18, 1990, 60)

Nintendo had finally become the One firm to rule them all. But the world of video games was set for great transformations, and Nintendo stood to lose Japan to the NEC PC-Engine and America to the Sega Genesis, for the reasons Dmitri Williams notes when assessing the “pattern of market dominance and failure” of the games industry:

As each firm became dominant, it acquired and then abused its market power. For Atari, it was an issue of hype, poor quality and unreasonable growth expectations. For Nintendo, it was first a lack of innovation in the late 1980s and then an abuse of its relationships with developers in the mid 1990s. (Williams 2002, 43)

Accordingly, many video game fans and publications point out the quality of the game library as the key factor that makes the Super NES one of the best consoles, if not the best console, of all time. Part of it came through Nintendo’s new rule on the maximum number of allowed publications. Instead of being limited to five titles per year, licensees now had a maximum of three games a year, but if one of their titles scored high enough on Nintendo’s review and approval system, it didn’t count toward that maximum. The system was perfect for Nintendo’s needs: that its own games do not get devalued by low-quality, cheaply sold games.

The system turned out too perfect, and the Super NES was soon awash with great high-quality games. This news was certainly good for consumers, but not so much for Nintendo, whose self-party business model relies first and foremost on selling its own games. Although the high licensing fees meant Nintendo collected easy revenue in the short term, they entailed a negative effect for its middle- and long-term positioning: they alienated licensees (on top of the content guidelines censorship issues, detailed in chapter 6) and diminished Nintendo’s strength as a provider of games. Through the SNES years, licensees such as Konami, Capcom, Square, Enix, and Koei rose to fame or increased their already burgeoning reputations (as noted in the introduction, they may arguably be said to have never been in better form before or since then). They carved a larger part of the software sales for themselves, a reality that cut right into the heart of the Nintendo Economic System.

The 1990s loomed over Nintendo like an incoming storm, marking the end of its Golden Age as the firm would gradually slide into its Silver Age.